Abstract

Digital transformation has received increasing attention from organizations and businesses that want to remain competitive in the digital world. Many banks have increasingly been embracing electronic commerce by providing electronic banking (e-banking) services. This study aimed to investigate the impact of electronic service (e-service) quality on customer intention to use video teller machine (VTM) services. Data were obtained from 450 customers in Vietnam, where digital transformation is a priority in the development strategy of the banking industry. Structural equation modeling reveals the positive impact of three e-service quality dimensions, including responsiveness, security, and interface quality, on the perceived ease of use (PEOU), perceived usefulness (PU), and attitude toward using VTM services. The findings also demonstrate that attitudes are positively related to intention toward using VTM services, and time-consciousness strengthens this relationship. These findings extend current knowledge about e-banking services in emerging markets and provide implications for bank managers and technology providers in promoting their service quality and customer use of VTM services.

1. Introduction

Digital transformation has received increasing attention from organizations and businesses that want to remain competitive in the digital world [1,2,3,4]. Essentially, it refers to “the use of new digital technologies, such as mobile, artificial intelligence, cloud, blockchain, and the Internet of things (IoT) technologies, to enable major business improvements to augment customer experience, streamline operations, or create a new business model” [5]. Many banks have considered digital transformation essential for improving service quality and increasingly deployed digital services such as internet banking, electronic payment wallets, and mobile banking applications [6]. These electronic banking (e-banking) services have proved to increase customer value and accelerated the industry’s growth.

Notably, COVID-19 has further encouraged firms to adopt and implement digital transformation [7]. The pandemic also accelerated the growth of e-banking and digital payment services [8,9,10], while traditional banking has been strongly affected. Specifically, consumers’ health concerns and restrictions such as lockdown and physical distancing have driven them towards e-banking adoption and usage, which is considered safer and more convenient compared to traditional banking services [11].

Digital transformation is a priority in the development strategy of Vietnam’s banking industry. With a population of over 97.58 million people [12], of which the proportion of young people is almost 70%, Vietnam is a potential digital banking market [13]. More than 62% of the population already own smartphones, and 64 million people are Internet users. Following the digital transformation trend, banks in Vietnam have been investing in innovating and digitizing their products and services. Video teller machine (VTM) services appeared in the Vietnam market at the end of 2017 [14]. A VTM machine is equipped with modern equipment and applies advanced technologies such as biometrics through fingerprint recognition and face recognition. Requests for support during use are handled remotely by a team of consultants. All implementation processes are appropriately designed, and users’ privacy and security are guaranteed. Notably, VTM services operate 24/7 and support customers with complicated transactions (e.g., opening accounts, depositing cash into accounts, and opening savings books) without requiring a transaction point. Several banks have applied VTM solutions under different aliases, e.g., LiveBank (Tien Phong Bank), SmartBank (MB Bank), and R-ATM (Vietin Bank), with the hope of meeting customers’ increasing demand for e-banking services and enhancing their electronic service (e-service) quality.

Santos [15] refers to e-service quality as “consumers’ overall evaluation and judgment of the excellence and quality of e-service offerings” within the virtual context (p. 235). In general, improving e-service quality is essential to obtaining a competitive advantage [16], enticing potential customers [17], and building greater relationships with customers [18,19]. In the banking industry, e-service quality appears to be an important driver of customer intention and behavior toward e-banking services [20,21,22]. Previous research has identified factors measuring e-service quality, and there is no consensus regarding its main dimensions [23,24]. Furthermore, some studies define service quality as a second-order construct [25,26]. Hence, there is insufficient understanding of the direct links between the components of e-service quality and other determinants of consumer behavior toward electronic banking (e-banking). Notably, the issue of e-service quality in Vietnam’s banking industry has been underestimated in the extant literature. This is surprising, given that Vietnam represents a colossal market opportunity for e-banking services [13].

This study aimed to contribute to the literature by developing and validating a model that explains how key components of e-service quality affect consumer intention to use VTM services, with a specific focus on Vietnam. It particularly concentrates on three important e-service quality dimensions of interface quality, responsiveness, and security, which play an essential role in consumer decisions in e-banking services [27,28,29,30,31]. It should be noted that previous research using the technology acceptance model (TAM) [32] and the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [33] reports that perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use (PEOU), and attitude are important determinants of consumer intention to use e-banking services [34,35,36,37]. Hence, this study postulates that the three e-service quality factors (i.e., interface quality, responsiveness, and security) affect PU, PEOU, and attitude, which in turn motivate consumers to use VTM services. In addition, the study seeks to examine the moderating role of time-consciousness, given that the impact of PU and attitude on intention may vary across consumers with different levels of awareness of time and how they spend it [38]. Essentially, the objectives of this study are threefold:

- (1)

- To examine the impact of responsiveness, security, and interface quality on PU, PEOU, and attitude towards using VTM services;

- (2)

- To investigate how PU, PEOU, and attitude affect intention to use VTM services;

- (3)

- To determine the moderating role of time-consciousness in the impact of PU and attitude on intention to use VTM services.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The second section reviews the relevant literature and develops the research hypotheses. Next, the third section describes the research methodology, followed by the fourth section presenting the results. Discussion of the findings and conclusions are demonstrated in the final section.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. VTM Services

A VTM is a 24/7 electronic banking outlet adopted in the banking sector recently. It can allow customers to complete basic transactions and provide them with different banking services and immediate assistance through live video conferencing with remote bank tellers. VTM services deployed in the Vietnamese market combine the characteristics of traditional ATM transactions and digitalized customer services based on innovative technology features. A VTM is generally designed to be wider than traditional ATMs, including large-screen interfaces with diverse functions. A VTM incorporates cameras and biometric identification systems that allow customers to use their fingerprints and faces to perform transactions and services. In addition, through the interface of the transaction machine, customers can interact with bank staff if they require further assistance. The ability to support customers to perform complicated transactions with high-security requirements and unrestricted time has demonstrated the great potential for VTM services to become an innovative solution in the future advancement of e-banking services.

2.2. E-Service Quality

Improving service quality is essential for service providers, including banks. According to Parasuraman et al. [39], service quality is attributed to “a form of attitude related but not equivalent to satisfaction, and results from the comparison of expectations with perceptions of performance” (p. 15). Extending this definition to the electronic domain, Santos [15] highlights that e-service quality reflects customers’ assessments and established perceptions of the excellence and quality of e-services. While the factors measuring e-service quality are diverse [15,40], this study focuses on three dimensions: responsiveness, security, and interface quality. These three factors are essential in consumer decision-making regarding e-banking services [34,35,36,37,41,42,43] and are highly relevant for VTM services.

2.2.1. Responsiveness

Bauer et al. [27] stated that responsiveness “encompasses the e-service provider’s ability to provide appropriate information in order to prevent further inconvenience and to be able to offer online warranties” (p. 157). Responsiveness is an essential component of e-service quality in the banking industry, which reflects how the providers are responsive to customer problems [27,28]. Customers are likely to find VTM services responsive because these services can quickly respond to customers’ needs and problems at their own convenience. This responsiveness can make consumers feel VTM services are useful and easy to use, and create positive attitudes toward using the services. Lu et al. [44] confirmed the relationship between responsiveness and PEOU in the Internet industry context. Other studies highlighted the positive impact of responsiveness on PU and attitude [45,46]. From the arguments above, the following hypotheses were developed:

Hypotheses 1

(H1). Responsiveness is positively related toPU.

Hypotheses 2

(H2). Responsiveness is positively related toPEOU.

Hypotheses 3

(H3). Responsiveness is positively related to customer attitude towardusing VTM services.

2.2.2. Security

Cox and Dale [47] defined security as the “technical safety of the network against fraud or hackers” (p. 44). Security in banking services is defined as “the security of credit card payments and the privacy of shared information during or after the sale” [48] (p. 356). Because there is no face-to-face interaction between customers and service providers, security and privacy issues become a significant concern for customers when using this novel form of e-banking service [49]. Therefore, ensuring security and personal information contributes to improving customers’ trust in the bank [50]. Security is an essential component of e-service quality in the banking sector [51,52]. The relationship between security and the acceptance of e-banking services has been highlighted in many studies [29,30]. Anouze and Alamro [53] pointed out the relationship between security and attitude when using e-banking services in Jordan. Meanwhile, Lallmahamood [54] demonstrated the positive impact of perceived security and privacy on PU and PEOU with internet banking services in Malaysia. From the above analysis, the authors proposed three research hypotheses:

Hypotheses 4

(H4). Security is positively related toPU.

Hypotheses 5

(H5). Security is positively related toPEOU.

Hypotheses 6

(H6). Security is positively related to consumer attitude towardusing VTM services.

2.2.3. Interface Quality

Interface quality reflects a well-designed and seemingly appealing website or device [55]. Interface user design should be displayed with suitable text sizes, images, and symbols to be easily identifiable and consistent in color [56]. The criteria used to evaluate the interface often includes well-organized, appealing, standardized navigation and consistency. Clarity layout is defined as the extent to which the user interface design structure appears to help (e.g., text, icons, and background). Design clarity is perceived as the degree to which the user interface’s structure helps customers quickly and easily navigate their option(s) of choice [41]. Poon [57] indicated that poor presentation and graphics layouts create confusion, negatively affecting customers’ desire to browse through electronic channels. Hong et al. [58] pointed out that the interface screen’s outline, buttons, and symbols positively influence customers’ PEOU for digital library services.

Similarly, Bashir and Madhavaiah [31] also demonstrated the direct impact of interfaces on the PEOU of internet banking services. Hassanein and Head [59] indicated that website interface elements influenced customers’ attitudes toward online shopping services. Since all transactions of the VTM services are done via screen, interface quality will significantly impact the attitude of customers who use the service. Finally, Calisir and Calisir [60] examined the positive impact of interface usability characteristics on PU. From the above arguments, the authors proposed the research hypotheses:

Hypotheses 7

(H7). Interface quality is positively related toPU.

Hypotheses 8

(H8). Interface quality is positively related toPEOU.

Hypotheses 9

(H9). Interface quality is positively related to customer attitude towardusing VTM services.

2.3. Perceived Usefulness

PU is defined as “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her job performance” [32] (p. 320). It is widely recognized as a motivator of customers’ attitudes and adoption behaviors toward banking services [36,61]. Jahangir and Begum [62] reported the relationship between PU and attitude toward e-banking services, providing support for other studies by Rose and Fogarty [63] and Chau and Lai [64]. Additionally, the positive impact of PU on intention was evident in the studies of Gu et al. [36], Wang et al. [35], and Shang et al. [65]. Therefore, customers’ perception of the usefulness of VTM services will be expected to enhance their attitude and intention toward using these services. The following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypotheses 10

(H10). PU is positively related to customerattitude towardusing VTM services.

Hypotheses 11

(H11). PU is positively related to customer intention to use VTM services.

2.4. Perceived Ease of Use

PEOU is defined as “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would be free of effort” [32] (p. 320). Doll et al. [66] stated that PEOU is the subjective level of confidence that an individual believes a novel system will not take much effort to be used. As mentioned earlier, VTMs have large screen interfaces with diverse functions, making it easier for customers to perform transactions. According to the TAM model, PEOU has a positive influence on PU and consumer attitude toward a technology [32]. Eriksson et al. [37], Gu et al. [36], and Lule et al. [67] confirmed the relationships between these three factors concerning e-banking services. It is, therefore, expected that consumers’ PEOU will enhance their PU and attitude toward VTM services. The research hypotheses were proposed:

Hypotheses 12

(H12). PEOU is positively related to customer PU.

Hypotheses 13

(H13). PEOU is positively related to customerattitude towardusing VTM services.

2.5. Attitude and Intention toward Using VTM Services

According to Ajzen [33], “intention” is a psychological state that sets an individual’s motivation, determination, and effort to perform the behavior. The intention is the immediate determinant of behavior [68]. When solutions to customers’ problems are available, their intention will provide the most accurate prediction of their behavior. Customer intention has been an essential topic in e-banking services research [69,70].

Attitude is considered a key factor affecting human decisions [71]. According to popular models explaining consumer behavior, such as the TAM model [32], the TRA [72], and the TPB [33], a favorable attitude often leads to purchase and consumption intention. Yeow et al. [34] verified the relationship between customers’ attitudes and behavioral intentions when using online banking services. Similarly, Wessels and Drennan [73] pointed out that attitude transforms perception into intention to use mobile banking services. From the above analysis, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypotheses 14

(H14). Attitude is positively related to intention to use VTM services.

2.6. The Moderating Effect of Time-Consciousness

Time is a limited resource in people’s lives, and most of us consider the efficiency of time before making behavioral decisions [38,74]. One of the advantages of e-banking services is the ability to save time for customers, which is presented by how customers can access the service at any time and place [75]. Kleijnen et al. [76] defined time-consciousness as “the extent to which consumers are aware of the passing of time and how they spend it” (p. 37). Time-conscious customers often easily recognize the scarcity of time resources, leading to product/service choices that offer the ability to use time more efficiently [76]. VTM services capable of serving customers 24/7 will be a convenient solution for customers who do not have time to search for banking offices to carry out transactions. Convenience and time-saving customer support are forecast to be the key to helping VTM services attract customers with a good sense of how to use their time effectively. Furthermore, Belanche et al. [38] demonstrated the moderating role of time-consciousness on the PU–intention and attitude–intention relationships in the research context of e-government service. From the above arguments, two research hypotheses were proposed as follows:

Hypotheses 15

(H15). The relationship between PU and use intention is positively moderated by time-consciousness.

Hypotheses 16

(H16). The relationship between attitude and use intention is positively moderated by time-consciousness.

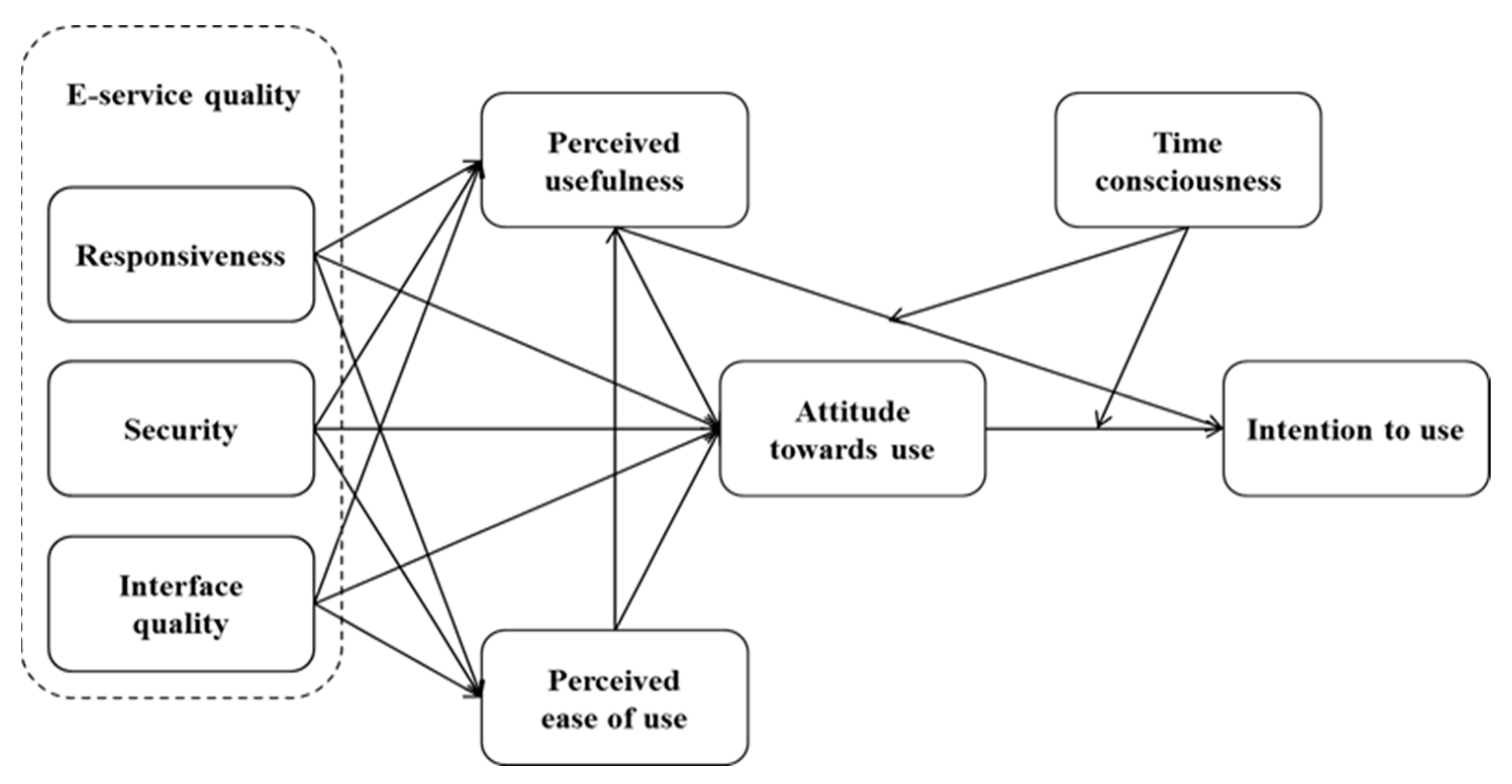

Figure 1 describes the theoretical research framework, including the hypothetical relationships between the variables.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Research Methodology and Data Collection

3.1. Survey Instrument and Measures

A survey instrument was developed to collect the data used to test the hypotheses. This survey instrument has three main parts. The first part includes the introduction and screening questions. The second part includes the questions/items used to measure the variables in the research model. The final part includes information related to demographic information and acknowledgments.

The measures of the variables were adapted from past banking service studies. The researchers chose high-reliability scales and then evaluated the items’ suitability from the selected scales. Two language experts translated the original scales from English into Vietnamese, which were then cross-checked in terms of terminology and meaning by two bilingual marketing professors [77]. In-depth interviews were used to further assess the measures’ quality and validity. Four interviews were conducted with experts in e-banking services, followed by 30 interviewers with customers using VTM services. After these interviews, some items were adapted to reflect the characteristics of VTM services. The items were operationalized on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 for “Strongly disagree” to 7 for “Strongly agree”. The measurement items ware presented later in this paper.

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

Data were collected from February to April 2021 using a convenient sampling method. The researchers attended popular VTM service locations in Hanoi (i.e., the capital of Vietnam) and conveniently approached respondents to request them to participate in the survey. Those respondents who agreed to participate in the survey were provided with facilities to complete the survey. The researchers were available to provide respondents with assistance in the survey completion and then collected completed forms. All respondents were informed about the research objectives and ensured anonymity and security. Their participation was voluntary, and completion of the survey was considered “informed consent”. A financial incentive of 25.000 VND (approximately 1 USD) was used to motivate respondents to participate in the survey.

After two months, a total of 469 surveys were returned. After the screening process, 19 surveys were removed because they contained unanswered questions. The final sample included 450 surveys. The demographic profile of the respondents is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the respondents.

3.3. Data Analysis Method

The study’s data were analyzed by IBM SPSS 25 and IBM AMOS 25 software. Cronbach Alpha, Harman’s single–factor test, and descriptive statistical analysis were analyzed with SPSS 25. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), latent common method variance factors, and structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis were performed using the AMOS 25 platform.

Measurement and structural models were assessed using the following indicators: Chi-square to the degree-of-freedom ratio (χ2/df); comparative fit index (CFI); Tucker–Lewis index (TLI); goodness–of–fit index (GFI); adjusted goodness–of–fit index (AGFI); normed fit index (NFI); and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). According to Hair et al. [78], the criteria include: TLI > 0.9; GFI > 0.9; CFI > 0.9; AGFI > 0.9; NFI > 0.9; χ2/df < 3; and RMSEA < 0.08.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Measurement Model, Construct Reliability, and Validity

CFA results demonstrate that the model included 268 degrees of freedom; χ2/df = 1.155 (<3); AGFI = 0.937; GFI = 0.952; CFI = 0.991; TLI = 0.989; NFI = 0.940 (>0.9); and RMSEA = 0.019 (<0.08). The results indicated that the model was suitable for the collected data.

Construct convergent and discriminant validity was assessed using guidelines by Hair et al. [78]. Accordingly, standardized factor loadings (FLs) needed to be greater than 0.5; composite reliability (CR) needed to be greater than 0.7; the average variance extracted (AVE) needed to be greater than 0.5; and the square root of AVE needed to be greater than the inter-construct correlation between constructs. Table 2 and Table 3 show that all the indices came within their requirements. Furthermore, the Cronbach Alpha coefficient values ranged from 0.755 to 0.867, ensuring the construct reliability [78,79].

Table 2.

Items, reliability, and convergent validity.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and discriminant validity.

4.2. Common Method Variance

The common method variance (CMV) is a problem that can negatively affect the measure performance since it can threaten reliability and validity and cause measurement errors [85]. This study followed Podsakoff et al.’s [85] suggestions for procedural and statistical remedies to minimize CMV occurrence. First, in the data collection process, anonymity and privacy were guaranteed. Secondly, the order of questions was randomized to reduce participants’ ability to predict the structure flow. Finally, Harman’s single factor test and latent common factor were applied to check potential CMV. A Harman’s single-factor test indicated that the single factor explained only 26.532% of the variables’ variance (less than 50%). The latent common factor test results demonstrated that the factor method accounted for 7.29% of the total variance (less than 25%). In addition, when comparing the estimated weight of the measurement model and the latent common factor model, the difference between the estimated weights did not exceed 0.2. Based on these findings and according to Malhotra et al. [86], it was reasonable to conclude that CMV did not appear to be a pervasive problem in this study.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

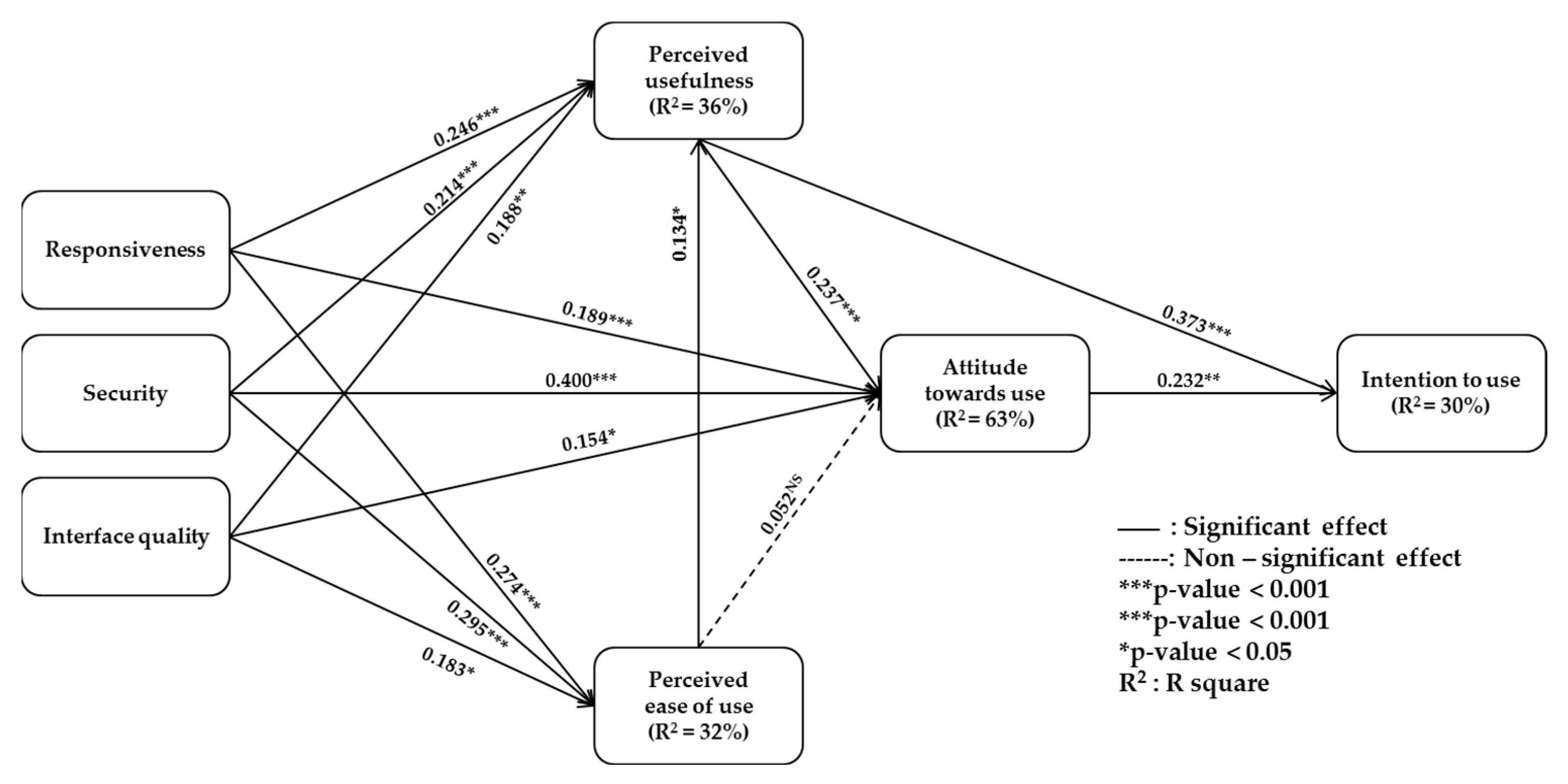

Structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis was applied to test the research hypotheses. The analysis results showed that the model included 178 degrees of freedom; χ2/df = 1.418 (less than 3); GFI = 0.954; AGFI = 0.938; TLI = 0.976; CFI = 0.980; NFI = 0.936 (greater than 0.9); RMSEA = 0.031 (less than 0.08); and p-value = 0.000 (less than 0.05). The model explained a significant 63% of consumers’ attitudes towards using VTM services and 30% of their intention to use the services (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

SEM model.

The results also showed that 13 of the 14 proposed research hypotheses were significant, albeit with different significance levels. Notably, the hypothesis that PEOU affects attitude was not supported (p = 0.393 > 0.05).

Table 4 summarizes the hypothesis testing results. The three dimensions of e-service quality significantly enhance PU, PEOU, and attitude towards using VTM services. Specifically, responsiveness was positively related to PU (β = 0.246, p < 0.001, t = 4.108, PEOU (β = 0.274, p < 0.001, t = 4.309) and attitude towards using VTM services (β = 0.189, p < 0.001, t = 3.294). In addition, security positively affected PU (β = 0.214, p < 0.001, t = 3.285), PEOU (β = 0.295, p < 0.001, t = 4.261), and attitude towards using VTM services (β = 0.400, p < 0.001, t = 6.075). Similarly, interface was positively related to PU (β = 0.188, p < 0.01, t = 2.938), PEOU (β = 0.139, p < 0.05, t = 2.002) and attitude towards using VTM services (β = 0.154, p < 0.05, t = 2.538).

Table 4.

Hypothesis testing results.

As expected, PU positively affected attitude towards using VTM services (β = 0.237, p < 0.001, t = 3.999) and the intention to use (β = 0.373, p < 0.001, t = 4.944). Moreover, PEOU was positively related to PU (β = 0.134, p < 0.05, t = 2.072). However, the effect of PEOU on attitude towards using VTM services was not significant (β = 0.052, p > 0.05, t = 0.854). Finally, attitude was positively related to intention to use VTM services (β = 0.232, p < 0.01, t = 3.059).

4.4. Moderating Effect Hypotheses Testing

The multi-group SEM method was applied to test the moderating role of time consciousness in the effects of PU and attitude on intention. The research sample was divided based on the customer’s assessment of time-consciousness, and the K-mean cluster division method was applied via SPSS 25, resulting in two groups of the samples identified:

Group 1: 214 customers (47.56%) have lower time-consciousness ratings.

Group 2: 236 customers (52.44%) have higher time-consciousness ratings.

The moderation test followed the recommendations of Hair et al. [78], including an invariance test followed by a structural model analysis.

According to Table 5, the fit indices of the configurational invariance (CI) and metric invariance (MI) models met the thresholds suggested by Hair et al. [78]. Furthermore, the p-value of the χ2 difference test was 0.755, so there was no difference between the two models. Hence, a structural model was established to evaluate the difference between the two groups of samples.

Table 5.

Result of invariance test.

The results of comparing the difference between the measurement weight model and the structural model show that the p = 0.000 < 0.05, ∆χ2 = 50.828, and ∆df = 14. Therefore, the unconstrained model was selected for evaluation [87]. According to Table 6, the results showed a difference between the two sample groups. Specifically, the impact of PU on intention was significantly higher for customers with higher time-consciousness (β = 0.451, p < 0.001) than those with lower time-consciousness (β = 0.230, p < 0.05). Similarly, the effect of attitude on intention was significantly stronger for customers who were more time-conscious (β = 0.392, p < 0.001) than those who were less conscious (β = 0.174, p > 0.05). Thus, it can be concluded that time-consciousness positively moderates the PU–intention and attitude–intention relationships.

Table 6.

Multi-group test results.

5. Discussion, Conclusion, and Implications

5.1. Discussion and Implications

The influences of digital transformation create many opportunities and threats for banks in providing services to customers. Many banks have gradually implemented e-services to increase customer convenience and value. Understanding how customers perceive and respond to these services will help banks develop appropriate strategies for improving the quality and adoption of such services. This study developed and validated a model explaining the impact of different e-service quality dimensions, PEOU and PU, on consumer attitude and intention toward a specific e-banking service, i.e., VTM services. It also highlighted the moderating role of time-consciousness in the model. This study also extended current knowledge about e-banking services in emerging markets by focusing on Vietnam.

5.1.1. Theoretical Implications

First, SEM results showed a positive impact of three e-service quality dimensions, including responsiveness, security, and interface quality, on PEOU, PU, and attitude. These findings enriched the research stream that highlights the role of e-service quality in enhancing consumer intention to adopt e-banking services [21]. Second, this study revealed the positive relationships between PU, attitude, and intention. These findings align with studies on consumer acceptance of new technology [32,36] and further support the application of TAM in the e-banking context.

Third, it is striking that the impact of PEOU on attitude towards using VTM services was insignificant, which contradicts many studies on technology acceptance and use [32,88]. One possible explanation for this finding is that some functions used in VTM services, such as fingerprint recognition and face recognition, have not yet operated stably, which might cause inconvenience for some customers. It should be mentioned that the findings also reveal that PEOU positively enhanced PU, which in turn increased the attitude toward using VTM services. That is, PEOU affected attitude indirectly via PU. These interesting findings suggest that more research is necessary to better understand the mechanism through which PEOU motivates consumers’ attitudes toward e-banking services.

Fourth, this study is among the first attempt to verify the moderating role of time-consciousness in the attitude–intention and PU–intention relationships. The findings show that the impact of PU and attitude on intention to use VTM services was more substantial for customers with higher time-consciousness. Such customers often carefully plan to use their time and pay attention to the time efficiency of activities in their lives [76]. Hence, banking services that can help them save time, such as VTM services, will strengthen the relationship between their perception/attitude and intention to use such services [38].

Finally, this study’s model validates the direct, indirect, and moderating effects of some key e-quality dimensions and determinants on consumer attitude and intention toward using VTM services. This model explained a significant 30% of the variance in consumer intention. Hence, it can serve as a theoretical framework for future studies into consumer intention and behavior toward e-banking services.

5.1.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study also provide implications for bank managers and VTM technology providers in improving e-service quality and promoting consumer use of e-banking services. Given this study’s context, these practical implications are particularly relevant to VTM services in emerging markets like Vietnam.

E-service quality dimensions directly impact PU, PEOU, and attitude and indirectly impact intention. Hence, promoting e-service quality dimensions, including responsiveness, security, and interface quality, is essential for banks. It should be noted that among the three dimensions, security has the most substantial impact on PEOU and attitude. Therefore, banks and VTM technology providers should make every effort to increase the security of VTM transactions and customer information. Although VTM integrates recent technologies ensuring consumer security, such as biometrics and fingerprint recognition, transactional data must also be protected. To improve responsiveness and interface quality, banks and VTM technology providers should improve data transmission, increase processing speed, enhance interface design, and provide additional customer support to better address customer problems.

It is essential to enhance the usefulness of VTM services by making the transactions more convenient and efficient. Notably, the VTM transaction system in Vietnam is still at a modest scale, which limits customers in many non-urban areas from accessing this service [89]. Thus, banks should make VTM services available in more locations to improve accessibility. Although PEOU does not directly impact attitude, it enhances PU, which in turn motivates attitude. Hence it would be beneficial to make it easier for customers to use VTM services. In this regard, instructions provided in the form of manuals at the points of presence or briefings on the interface screen should be utilized. In addition, to let customers use the services without obstacles, the system’s quality needs to be upgraded periodically, including checking to reduce the range of errors that might incur during transactions.

Given the moderating role of time-consciousness, an important target market for VTM services is those who are conscious about their time and how to utilize it. Time-conscious consumers are aware of the scarcity of time as an important resource and value time-convenience. Information and communication programs should therefore highlight the time-saving attribute of VTM services and that such services can be used anytime during the day. Such programs should use different media channels such as TV, magazines, websites, social media, and bank branches and VTM locations. Currently, the VTM services deployed by banks in Vietnam can only deliver two-thirds of the total available banking services [89]. Therefore, it is necessary to gradually incorporate more services that VTM can perform.

5.2. Conclusion and Future Research

This study examined the impact of electronic service (e-service) quality on customer intention to use VTM services. The findings demonstrate the positive impact of three e-service quality dimensions, including responsiveness, security, and interface quality, on PEOU, PU, and attitude toward using VTM services. In addition, attitude is positively related to intention toward using VTM services, and time-consciousness positively moderates this relationship.

Although this study successfully addressed the research objectives, it has several limitations. First, VTM services are relatively new and have been implemented in only big cities such as Hanoi. Hence, the sample in this study mainly consisted of urban residents. It is suggested that future research should investigate both urban and rural customers. Second, respondents aged 45 and over accounted for only 10% of this study’s sample. Thus, future research should pay more attention to this market segment. In this regard, qualitative research, such as ethnography and life stories, could be used to approach consumers aged 45 and over in rural areas. Third, the cross-sectional survey used in this study is limited in explaining the causal relationships between the variables. Future studies could address this by using longitudinal surveys or experimental methods. Fourth, future studies are advised to test the model validated in the current study in other emerging markets (e.g., China, India, Indonesia, and Malaysia). Fifth, it would be beneficial to extend this research model by including other dimensions of e-service quality (e.g., reliability, competence) and users’ habits, personal need, technological knowledge, and socio-demographic variables such as age, gender, education, income, and religious beliefs. Finally, future research should complement this study by exploring if consumers expect new features and services provided by VTM. This can be done through focus groups, in-depth interviews, or experiments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.V.N., T.D.V., N.N., B.K.N., T.M.N.N. and B.D.; methodology, H.V.N., T.D.V., B.K.N. and N.N.; formal analysis, H.V.N., T.D.V. and T.M.N.N.; writing—original draft preparation, H.V.N., T.D.V., N.N., T.M.N.N. and B.D; writing—review and editing, H.V.N., T.D.V., N.N., B.K.N., T.M.N.N. and B.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. The research was conducted in line with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gaglio, C.; Kraemer-Mbula, E.; Lorenz, E. The effects of digital transformation on innovation and productivity: Firm-level evidence of South African manufacturing micro and small enterprises. Technol. Forecast. Social Chang. 2022, 182, 121785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekic, Z.; Koroteev, D. From disruptively digital to proudly analog: A holistic typology of digital transformation strategies. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 62, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margiono, A. Digital transformation: Setting the pace. J. Bus. Strategy 2020, 42, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.H.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Nguyen, N.; Pervan, S. Development and validation of a scale measuring hotel website service quality (HWebSQ). Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.S.; Wäger, M. Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, F.; Špaček, M. Digital transformation in banking: A managerial perspective on barriers to change. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, S.; Weber, E.; Büttgen, M.; Huber, A. Leadership matters in crisis-induced digital transformation: How to lead service employees effectively during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 32, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amin, M.; Arefin, M.S.; Alam, M.S.; Rasul, T.F. Understanding the predictors of rural customers’ continuance intention toward mobile banking services applications during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Glob. Mark. 2021, 35, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, H.; Tran, V.T.; Nguyen, T.H. Consumer attitudes toward facial recognition payment: An examination of antecedents and outcomes. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 40, 511–535. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Nguyen, N.; Nguyen, H.V.; Saleem, M.A. Consumers’ perceived value and use intention of cashless payment in the physical distancing context: Evidence from an Asian emerging market. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, I.U.; Awan, T.M. Impact of e-banking service quality on e-loyalty in pandemic times through interplay of e-satisfaction. Vilakshan-XIMB J. Manag. 2020, 17, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSO. Population, Labor and Employment Infographic in 2020; General Statistics Office of Vietnam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2021.

- Dinh, V.S.; Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, T.N. Cash or Cashless? Promoting consumers’ adoption of mobile payments in an emerging economy. Strateg. Dir. 2018, 34, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tâm, H. Live Bank Automatic Bank First Appeared in Vietnam. 2017. Available online: https://baodautu.vn/ngan-hang-tu-dong-live-bank-lan-dau-tien-co-mat-tai-viet-nam-d59254.html (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Santos, J. E-service quality: A model of virtual service quality dimensions. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2003, 13, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Lu, H.; Hou, M.; Cui, K.; Darbandi, M. Customer satisfaction with bank services: The role of cloud services, security, e-learning and service quality. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Salam, A.F. An empirical assessment of service quality, service consumption experience and relational exchange in electronic mediated environment (EME). Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 22, 843–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutam, D.; Ganguli, S.; Gopalakrishna, B. Technology readiness and e-service quality–impact on purchase intention and loyalty. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2022, 40, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdirad, M.; Krishnan, K. Examining the impact of E-supply chain on service quality and customer satisfaction: A case study. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2022, 14, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.; Voss, C. The impacts of e-service quality on customer behaviour in multi-channel e-services. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2012, 23, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Bhatti, S.H.; Hwang, Y. E-service quality and actual use of e-banking: Explanation through the Technology Acceptance Model. Inf. Dev. 2020, 36, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oni, A.A.; Adewoye, O.J.; Eweoya, I.O. E-banking users’ behaviour: E-service quality, attitude, and customer satisfaction. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2016, 34, 247–367. [Google Scholar]

- Barrutia, J.M.; Gilsanz, A. e-Service quality: Overview and research agenda. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2009, 1, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loonam, M.; O’loughlin, D. An observation analysis of e-service quality in online banking. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2008, 13, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A. Perceptions of Internet banking users—A structural equation modelling (SEM) approach. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2018, 30, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.-F.; Ho, C.-H.; Chung, M.-H. Theoretical integration of user satisfaction and technology acceptance of the nursing process information system. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, H.H.; Hammerschmidt, M.; Falk, T. Measuring the quality of e-banking portals. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2005, 23, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.A. Gender, e-banking, and customer retention. J. Glob. Mark. 2019, 32, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polatoglu, V.N.; Ekin, S. An empirical investigation of the Turkish consumers’ acceptance of Internet banking services. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2001, 19, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, J.M.C.; Mazzon, J.A. Adoption of internet banking: Proposition and implementation of an integrated methodology approach. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2007, 25, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, I.; Madhavaiah, C. Consumer attitude and behavioural intention towards Internet banking adoption in India. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2015, 7, 67–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeow, P.H.; Yuen, Y.Y.; Tong, D.Y.K.; Lim, N. User acceptance of online banking service in Australia. Commun. IBIMA 2008, 1, 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.S.; Wang, Y.M.; Lin, H.H.; Tang, T.I. Determinants of user acceptance of Internet banking: An empirical study. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2003, 14, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.-C.; Lee, S.-C.; Suh, Y.-H. Determinants of behavioral intention to mobile banking. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 11605–11616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, K.; Kerem, K.; Nilsson, D. Customer acceptance of internet banking in Estonia. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2005, 32, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C. Integrating trust and personal values into the Technology Acceptance Model: The case of e-government services adoption. Cuad. Econ. Dir. Empresa 2012, 15, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L. SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Parasuraman, A.; Malhotra, A. A Conceptual Framework for Understanding e-Service Quality: Implications for Future Research and Managerial Practice; Marketing Science Institute: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; Volume 115. [Google Scholar]

- Fassnacht, M.; Koese, I. Quality of electronic services: Conceptualizing and testing a hierarchical model. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 9, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, S.; Arora, S. Customers’ usage behaviour of e-banking services: Interplay of electronic banking and traditional banking. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 27, 2169–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetteh, J.E. Electronic Banking Service Quality: Perception of Customers in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. J. Internet Commer. 2022, 21, 104–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Lai, I.K.W.; Liu, Y. The consumer acceptance of smart product-service systems in sharing economy: The effects of perceived interactivity and particularity. Sustainability 2019, 11, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Lee, W.-j. The effects of technology readiness and technology acceptance on NFC mobile payment services in Korea. J. Appl. Bus. Res. JABR 2014, 30, 1615–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzi, S.W. A theoretical Model for Internet banking: Beyond perceived usefulness and ease of use. Arch. Bus. Res. 2014, 2, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Dale, B.G. Service quality and e-commerce: An exploratory analysis. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2001, 11, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, B.B.; Beatty, S.E. Satisfiers and dissatisfiers in the online environment: A critical incident assessment. J. Serv. Res. 2008, 10, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Jebarajakirthy, C. The influence of e-banking service quality on customer loyalty: A moderated mediation approach. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 1119–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singu, H.B.; Chakraborty, D. I have the bank in my pocket: Theoretical evidence and perspectives. J. Public Aff. 2021, 22, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfinbarger, M.; Gilly, M.C. eTailQ: Dimensionalizing, measuring and predicting etail quality. J. Retail. 2003, 79, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blut, M.; Chowdhry, N.; Mittal, V.; Brock, C. E-service quality: A meta-analytic review. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 679–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anouze, A.L.M.; Alamro, A.S. Factors affecting intention to use e-banking in Jordan. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 38, 86–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallmahamood, M. An examination of Individual perceived security and privacy of the internet in Malaysia and the influence of this on their intention to use E-commerce: Using an extension of the technology acceptance model. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 1970, 12, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R.; Wang, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, L.; Guo, H. Measuring e-service quality and its importance to customer satisfaction and loyalty: An empirical study in a telecom setting. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 19, 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladwani, A.M.; Palvia, P.C. Developing and validating an instrument for measuring user-perceived web quality. Inf. Manag. 2002, 39, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, W.C. Users’ adoption of e-banking services: The Malaysian perspective. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2008, 23, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Thong, J.Y.; Wong, W.-M.; Tam, K.-Y. Determinants of user acceptance of digital libraries: An empirical examination of individual differences and system characteristics. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2002, 18, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, K.; Head, M. Manipulating perceived social presence through the web interface and its impact on attitude towards online shopping. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2007, 65, 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisir, F.; Calisir, F. The relation of interface usability characteristics, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use to end-user satisfaction with enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2004, 20, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guriting, P.; Ndubisi, N.O. Borneo online banking: Evaluating customer perceptions and behavioural intention. Manag. Res. News 2006, 29, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadim, J.; Noorjahan, B. The role of perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, security and privacy, and customer attitude to engender customer adaptation in the context of electronic banking. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2008, 2, 032–040. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, J.; Fogarty, G.J. Determinants of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use in the technology acceptance model: Senior consumers’ adoption of self-service banking technologies. In Proceedings of the 2nd Biennial Conference of the Academy of World Business, Marketing and Management Development: Business Across Borders in the 21st Century, Paris, France, 10–13 July 2006; pp. 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, P.Y.; Lai, V.S. An empirical investigation of the determinants of user acceptance of internet banking. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2003, 13, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, R.-A.; Chen, Y.-C.; Shen, L. Extrinsic versus intrinsic motivations for consumers to shop on-line. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, W.J.; Hendrickson, A.; Deng, X. Using Davis’s perceived usefulness and ease-of-use instruments for decision making: A confirmatory and multigroup invariance analysis. Decis. Sci. 1998, 29, 839–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lule, I.; Omwansa, T.K.; Waema, T.M. Application of technology acceptance model (TAM) in m-banking adoption in Kenya. Int. J. Comput. ICT Res. 2012, 6, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Q.A.; Hens, L.; Nguyen, N.; MacAlister, C.; Lebel, L. Explaining intentions by vietnamese schoolchildren to adopt pro-environmental behaviors in response to climate change using theories of persuasive communication. Environ. Manag. 2020, 66, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, N.M.; Abdulla, A.K.M.A. The influence of attraction on internet banking: An extension to the trust-relationship commitment model. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2006, 24, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawashdeh, A. Factors affecting adoption of internet banking in Jordan: Chartered accountant’s perspective. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 510–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.A.; Hens, L.; MacAlister, C.; Johnson, L.; Lebel, B.; Bach Tan, S.; Nguyen, H.M.; Nguyen, T.N.; Lebel, L. Theory of reasoned action as a framework for communicating climate risk: A case study of schoolchildren in the Mekong Delta in Vietnam. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 10, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Wessels, L.; Drennan, J. An investigation of consumer acceptance of M-banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2010, 28, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstholt, J. The effect of time pressure on decision-making behaviour in a dynamic task environment. Acta Psychol. 1994, 86, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nysveen, H.; Pedersen, P.E.; Thorbjørnsen, H. Intentions to use mobile services: Antecedents and cross-service comparisons. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijnen, M.; De Ruyter, K.; Wetzels, M. An assessment of value creation in mobile service delivery and the moderating role of time consciousness. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, J.; Pennell, B.E.; Schoua-Glusberg, A. Survey questionnaire translation and assessment. In Methods for Testing and Evaluating Survey Questionnaires; Presser, S., Rothgeb, J.M., Couper, M.P., Lessler, J.T., Martin, E., Martin, J., Singer, E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 453–473. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.S.; Shaikh, N.M. Internet banking and quality of service: Perspectives from a developing nation in the Middle East. Online Inf. Rev. 2008, 32, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Riel, A.C.; Liljander, V.; Jurriens, P. Exploring consumer evaluations of e-services: A portal site. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2001, 12, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, M.; Cai, S. The key determinants of internet banking service quality: A content analysis. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2001, 19, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Prasad, J. A field study of the adoption of software process innovations by information systems professionals. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2000, 47, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.Y.; Fang, K. The use of a decomposed theory of planned behavior to study Internet banking in Taiwan. Internet Res. 2004, 14, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Patil, A. Common method variance in IS research: A comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Leiva, F.; Climent-Climent, S.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. Determinants of intention to use the mobile banking apps: An extension of the classic TAM model. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2017, 21, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, Q. Automated Banking: A New Factor in the Process of Digitization. 2021. Available online: https://bankingplus.vn/ngan-hang-tu-dong-nhan-to-moi-tren-duong-dua-so-hoa-99648.html (accessed on 19 May 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).