Self-Disclosure to a Robot: Only for Those Who Suffer the Most

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Research Question and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Design

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Apparatus and Materials

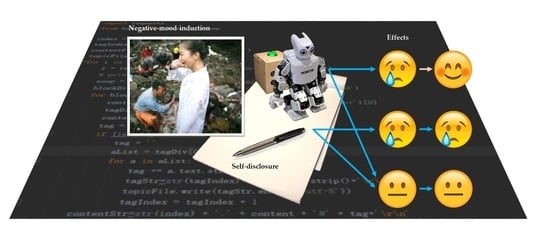

2.3.1. Video Materials

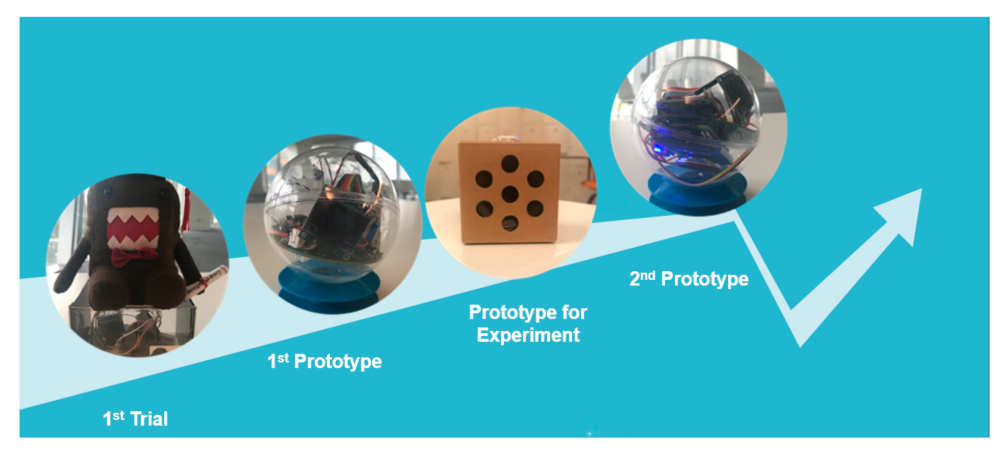

2.3.2. Robot Embodiment

2.3.3. Self-Disclosure Chatbot

2.4. Measures

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Manipulation Check: Emotional Effects after Negative-Mood Induction and after Treatment

3.3. Effect of Media (Robot vs. Writing) on Valence and Relevance

- Valence bipolar: ΔVal = MValA–MValB;

- Positive Valence: ΔValP = MValAi–MValBi;

- Negative Valence: ΔValN = MValAc–MValBc.

3.3.1. Effects on Bipolar Valence and Relevance

3.3.2. Effects on Positive Valence, Negative Valence and Relevance

3.4. Effect of Media on Valence and Relevance for Those Who Felt Most Negative

3.4.1. Valence as a Bipolar Scale in High-Negative Subjects

3.4.2. Positive and Negative Valence as Two Unipolar Scales in Highly Negative Subjects

3.4.3. Exploratory Analyses

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

5.1. Future Work

5.2. Design Practice

The robot answered my questions in weird ways sometimes, and repeated some questions. I think the unexpected movement of the robot was the best part of the experiment. It affectively changed my mood. Not so much the conversation itself.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Bu, F.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health 2020, 186, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Loneliness during a strict lockdown: Trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 United Kingdom adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killgore, W.D.; Cloonan, S.A.; Taylor, E.C.; Miller, M.A.; Dailey, N.S. Three months of loneliness during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Z.; Wang, S. Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, I.F.; Park, S. Alarming levels of psychiatric symptoms and the role of loneliness during the COVID-19 epidemic: A case study of Hong Kong. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.Y.; Townson, A.T.; Kapur, M.; Ferreira, A.F.; Nunn, R.; Galante, J.; Phillips, V.; Gentry, S.; Usher-Smith, J.A. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness during COVID-19 physical distancing measures: A rapid systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopwood, T.L.; Schutte, N.S. Psychological outcomes in reaction to media exposure to disasters and large-scale violence: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Violence 2017, 7, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Joiner, T.E.; Rogers, M.L.; Martin, G.N. Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 6, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frijda, N. The Laws of Emotion; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, J.; Li, Y.; Valdesolo, P.; Kassam, K. Emotion and decision making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Croyle, R.T.; Uretzky, M.D. Effects of mood on self-appraisal of health status. Health Psychol. 1987, 6, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, L.; Edelstein, R. Emotion and memory narrowing: A review and goal relevance approach. Cogn. Emot. 2009, 23, 833–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, T.J. Emotions and health. In Emotions: Current Issues and Future Directions; Mayne, T.J., Bonanno, G.A., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 361–397. [Google Scholar]

- Thayer, J.F.; Ruiz-Padial, E. Neurovisceral integration, emotions and health: An update. Int. Congr. Ser. 2006, 1287, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, S.; Gallagher, M.; Lopez, S. Is the emotion-health connection a “first-world problem”? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consedine, N.S.; Moskowitz, J.T. The role of discrete emotions in health outcomes: A critical review. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 2007, 12, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, T.J. Negative affect and health: The importance of being earnest. Cogn. Emot. 1999, 13, 601–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubzansky, L.D.; Kawachi, I. Going to the heart of the matter: Do negative emotions cause coronary heart disease? J. Psychosom. Res. 2000, 48, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnemans, J.; Frijda, N. The determinants of subjective emotional intensity. Cogn. Emot. 1995, 9, 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. Emotion and Adaptation; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, B. Ideas and Realities of Emotion; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, K.R. What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Soc. Sci. Inf. 2005, 44, 695–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuman, V.; Sander, D.; Scherer, K.R. Levels of valence. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barrett, L. Valence is a basic building block of emotional life. J. Res. Pers. 2006, 40, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, K.R. Appraisal considered as a process of multilevel sequential checking. In Appraisal Processes in Emotion: Theory, Methods, Research; Scherer, K.R., Schorr, A., Johnstone, T., Eds.; Oxford University: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 92–120. [Google Scholar]

- Frijda, N. The Emotions (Studies in Emotion and Social Interaction); Cambridge University: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, K.R. The nature and dynamics of relevance and valence appraisals: Theoretical advances and recent evidence. Emot. Rev. 2013, 5, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, K.R. On the nature and function of emotions: A component process approach. In Approaches to Emotion; Scherer, K.R., Ekman, P., Eds.; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1984; pp. 293–317. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine, J.; Scherer, K.; Soriano, C. Components of Emotional Meaning. A Sourcebook; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Farber, B. Self-Disclosure in Psychotherapy; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, J. Written emotional expression: Effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 66, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennebaker, J.W. Traumatic experience and psychosomatic disease. Exploring the roles of behavioural inhibition, obsession, and confiding. Can. Psychol. 1985, 26, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, W.; Malouff, J.; Osland, K. Written emotional expression as a coping method in child protective services officers. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemenover, S. Individual differences in rate of affect change: Studies in affective chronometry. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horneffer, K.; Jamison, P. The emotional effects of writing about stressful experiences: An exploration of moderators. Occup. Health Care 2002, 16, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, M.; Malouff, J.; Byrne, B. The efficacy of written emotional expression in the reduction of psychological distress in police officers. Int. J. Police Sci. Manag. 2007, 9, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frattaroli, J. Experimental disclosure and its moderators: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 823–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennebaker, J.; Francis, M. Cognitive, emotional, and language processes in disclosure. Cogn. Emot. 1996, 10, 601–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, J.; Glenwick, D. Effects of expressive writing on standardized graduate entrance exam performance and physical health functioning. J. Psychol. 2009, 143, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisina, P.G.; Borod, J.C.; Lepore, S.J. A meta-analysis of the effects of written emotional disclosure on the health outcomes of clinical populations. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2004, 192, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoe, P. Using patient writings in psychotherapy: Review of evidence for expressive writing and cognitive-behavioral writing therapy. Am. J. Psychiatry Resid. J. 2016, 11, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lumley, M. Alexithymia, emotional disclosure, and health: A program of research. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 1271–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennebaker, J. Putting stress into words: Health, linguistic, and therapeutic implications. Behav. Res. 1993, 31, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, J.; Beall, S. Confronting a traumatic event: Toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1986, 95, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E.; Segal, D. Emotional processing in vocal and written expression of feelings about traumatic experiences. J. Trauma. Stress 1994, 7, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO’s Mental Health Atlas 2017 Highlights Global Shortage of Health Workers Trained in Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/hrh/news/2018/WHO-MentalHealthAtlas2017-highlights-HW-shortage/en/ (accessed on 6 June 2018).

- Weizenbaum, J. ELIZA—A computerS program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Commun. ACM 1966, 9, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffarizadeh, K.; Boodraj, M.; Alashoor, T.M. Conversational assistants: Investigating privacy concerns, trust, and self-disclosure. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information System: Transforming Society with Digital Innovation (ICIS ’17), Seoul, Korea, 10–13 December 2017; Kim, Y.J., Agarwal, R., Lee, J.K., Eds.; Association for Information Systems: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hoorn, J.F.; Konijn, E.A.; Germans, D.M.; Burger, S.; Munneke, A. The in-between machine: The unique value proposition of a robot or why we are modelling the wrong things. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART), Lisbon, Portugal, 10–12 January 2015; Loiseau, S., Filipe, J., Duval, B., van den Herik, J., Eds.; ScitePress: Lisbon, Portugal, 2015; pp. 464–469. [Google Scholar]

- Wada, K.; Shibata, T.; Saito, T.; Sakamoto, K.; Tanie, K. Psychological and social effects of one year robot assisted activity on elderly people at a health service facility for the aged. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA ’05), Barcelona, Spain, 18–22 April 2005; pp. 2785–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibb, L.A.; Birnie, K.A.; Nathan, P.C.; Beran, T.N.; Hum, V.; Victor, J.C.; Stinson, J.N. Using the MEDiPORT humanoid robot to reduce procedural pain and distress in children with cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e27242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, T.-H.-H.; Tapus, A. The role of motivational robotic assistance in reducing user’s task stress. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2015, 7, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabibihan, J.; Javed, H.; Ang, M.; Aljunied, S. Why robots? A survey on the roles and benefits of social robots in the therapy of children with autism. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2013, 5, 593–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, B.; Amirabdollahian, F.; Ji, Z.; Dautenhahn, K. Tactile interaction with a humanoid robot for children with autism: A case study analysis involving user requirements and results of an initial implementation. In Proceedings of the 19th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN ’10), Viareggio, Italy, 13–15 September 2010; Avizzano, C.A., Ruffaldi, E., Eds.; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kozima, H.; Nakagawa, C.; Yasuda, Y. Interactive robots for communication care: A case-study in autism therapy. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (ROMAN ‘05), Nashville, TN, USA, 13–15 August 2005; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderborght, B.; Simut, R.; Saldien, J.; Pop, C.; Rusu, A.S.; Pintea, S.; Dirk, L.; David, D.O. Using the social robot Probo as a social story telling agent for children with ASD. Interact. Stud. Soc. Behav. Commun. Biol. Artif. Syst. 2012, 13, 348–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapus, A.; Peca, A.; Aly, A.; Pop, C.; Jisa, L.; Pintea, S.; David, D.O. Children with autism social engagement in interaction with Nao, an imitative robot. A series of single case experiments. Interact. Stud. Soc. Behav. Commun. Biol. Artif. Syst. 2012, 13, 315–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumazaki, H.; Warren, Z.; Swanson, A.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Kikuchi, M. Can robotic systems promote self-disclosure in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder? A pilot study. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pu, L.; Moyle, W.; Jones, C.; Todorovic, M. The effectiveness of social robots for older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Gerontologist 2019, 59, e37–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libin, A.V.; Libin, E.V. Person-robot interactions from the robopsychologists’ point of view: The robotic psychology and robotherapy approach. Proc. IEEE 2004, 92, 1789–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costescu, C.A.; Vanderborght, B.; David, D.O. The effects of robot-enhanced psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2014, 18, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kidd, C.; Taggart, W.; Turkle, S. A sociable robot to encourage social interaction among the elderly. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA ’06), Orlando, FL, USA, 15–19 May 2006; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 3972–3976. [Google Scholar]

- Wada, K.; Shibata, T. Social effects of robot therapy in a care house-change of social network of the residents for two months. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA ’07), Roma, Italy, 10–14 April 2007; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 1250–1255. [Google Scholar]

- Bolls, P.; Lang, A.; Potter, R. The effects of message valence and listener arousal on attention, memory, and facial muscular responses to radio advertisements. Commun. Res. 2001, 28, 627–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lang, A.; Shin, M.; Lee, S. Sensation seeking, motivation, and substance use: A dual system approach. Media Psychol. 2005, 7, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedlecka, E.; Denson, T. Experimental methods for inducing basic emotions: A qualitative review. Emot. Rev. 2019, 11, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelaro, N.; Nneji, V.; Ju, W.; Hinds, P. Tell me more designing HRI to encourage more trust, disclosure, and companionship. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI ’16), Christchurch, New Zealand, 7–10 March 2016; Bartneck, C., Nagai, Y., Paiva, A., Šabanović, S., Eds.; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Złotowski, J.; Sumioka, H.; Nishio, S.; Glas, D.F.; Bartneck, C.; Ishiguro, H. Appearance of a robot affects the impact of its behaviour on perceived trustworthiness and empathy. Paladyn. J. Behav. Robot. 2016, 7, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salem, M.; Lakatos, G.; Amirabdollahian, F.; Dautenhahn, K. Would you trust a (faulty) robot: Effects of error, task type and personality on human-robot cooperation and trust. In Proceedings of the 10th Annual ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI ’15), Portland, OR, USA, 2–5 March 2015; ACM: New York, NY USA, 2015; pp. 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nystul, M. Introduction to Counseling: An Art and Science Perspective, 5th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, I.; Taylor, D. Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships; Holt: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, T.; Kawakami, K. Relationships between robot’s self-disclosures and human’s anxiety toward robots. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conferences on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology (WI-IAT’11), Lyon, France, 22–27 August 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psychopathology Committee of the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry Reexamination of therapist self-disclosure. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001, 52, 1489–1493. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Ellsworth, P.C. Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 813–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, P.; Oceja, L. Drawing mixed emotions: Sequential or simultaneous experiences? Cogn. Emot. 2007, 21, 422–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. Mixed emotions viewed from the psychological constructionist perspective. Emot. Rev. 2017, 9, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Introduction to the special section on the structure of emotion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 803–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Carroll, J.M. On the bipolarity of positive and negative affect. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Carroll, J.M. The phoenix of bipolarity: Reply to Watson and Tellegen. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 611–617. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, L.M.; Furberg, C.D.; DeMets, D.L. Fundamentals of Clinical Trials; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent, E. Interactions with robots: The truths we reveal about ourselves. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2017, 68, 627–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Slavin-Spenny, O.; Cohen, J.; Oberleitner, L.; Lumley, M. The effects of different methods of emotional disclosure: Differentiating post-traumatic growth from stress symptoms. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 993–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murray, E.J.; Lamnin, A.D.; Carver, C.S. Emotional expression in written essays and psychotherapy. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1989, 8, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, E.M.; Sloan, D.P.; Marx, B. Getting to the heart of the matter: Written disclosure, gender, and heart rate. Psychosom. Med. 2005, 67, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sloan, D.M.; Marx, B.P.; Epstein, E.M.; Lexington, J.M. Does altering the writing instructions influence outcome associated with written disclosure? Behav. Ther. 2007, 38, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perez, S.; Penate, W.; Bethencourt, J.; Fumero, A. Verbal emotional disclosure of traumatic experiences in adolescents: The role of social risk factors. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa, T.; Cauda, F.; Crini, M.; Tatu, M.; Celeghin, A.; De Gelder, B.; Tamietto, M. Temporal and spatial neural dynamics in the perception of basic emotions from complex scenes. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2014, 9, 1690–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassenzahl, M. Emotions can be quite ephemeral; we cannot design them. Interactions 2004, 11, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, A.M.; Terry, P.C. The nature of mood: Development of a conceptual model with a focus on depression. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2000, 12, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qiao-Tasserit, E.; Garcia Quesada, M.; Antico, L.; Bavelier, D.; Vuilleumier, P.; Pichon, S. Transient emotional events and individual affective traits affect emotion recognition in a perceptual decision-making task. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauss, I.; Robinson, M. Measures of emotion: A review. Cogn. Emot. 2009, 23, 209–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erevelles, S. The role of affect in marketing. J. Bus. Res. 1998, 42, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P. The three-system approach to emotion. In The Structure of Emotion; Birbaum, N., Ohman, A., Eds.; Hogrefe: Bern, Switzerland, 1993; pp. 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, K.R.; Zentner, M.R. Emotional effects of music: Production rules. In Music and Emotion: Theory and Research; Juslin, P.N., Sloboda, J.A., Eds.; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 361–392. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, D. Language and the Internet; Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rezabek, L.L.; Cochenour, J.J. Visual cues in Computer-Mediated Communication: Supplementing text with emoticons. J. Vis. Lit. 1998, 18, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A. Emotional expression online: Gender difference in emotion use. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2000, 3, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Yang, Y. Pragmatic functions of emoji in internet-based communication—A corpus-based study. Asian-Pac. J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 2018, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walsh, M.F.; Winterich, K.P.; Mittal, V. Do logo redesigns help or hurt your brand? The role of brand commitment. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2010, 19, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mood Induction | ||

| t | p | n | |

| MValBi | 8.67 | 0.00001 | 45 |

| MValBc | 16.44 | 0.00001 | 45 |

| MValBi | 7.00 | 0.00001 | 31 |

| MValBc | 15.38 | 0.00001 | 31 |

| Variables | Treatment | ||

| t | p | n | |

| MValAi | 17.83 | 0.00001 | 45 |

| MValAc | 10.35 | 0.00001 | 45 |

| MValAi | 18.65 | 0.00001 | 31 |

| MValAc | 9.39 | 0.00001 | 31 |

| Variables | Before–After Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| T | p | n | |

| MValBc–MValAc | 9.34 | 0.00001 | 45 |

| MValBc–MValAc | 9.42 | 0.00001 | 31 |

| MValBi–MValAi | −7.16 | 0.00001 | 45 |

| MValBi–MValAi | −7.24 | 0.00001 | 31 |

| Variables | Robot | Writing | ||||

| Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | |

| ∆Val | 1.77 | 1.26 | 24 | 1.11 | 0.81 | 21 |

| ∆ValP | 1.75 | 1.31 | 24 | 0.89 | 1.06 | 21 |

| ∆ValN | 1.78 | 1.30 | 24 | 1.32 | 0.84 | 21 |

| MRel | 4.19 | 0.99 | 24 | 3.98 | 1.33 | 21 |

| MNov | 4.10 | 0.86 | 24 | 3.42 | 0.77 | 21 |

| N = 45 | ||||||

| Variables | Robot | Writing | ||||

| Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | |

| ∆Val | 1.98 | 1.11 | 17 | 1.33 | 0.83 | 14 |

| ∆ValP | 1.99 | 1.08 | 17 | 1.05 | 1.17 | 14 |

| ∆ValN | 1.97 | 1.27 | 17 | 1.61 | 0.76 | 14 |

| MRel | 4.35 | 0.96 | 17 | 4.27 | 1.08 | 14 |

| MNov | 4.13 | 0.95 | 17 | 3.53 | 0.78 | 14 |

| n = 31 | ||||||

| Robot vs. Writing on: | ||||||

| V | F | df1,2 | p | ηp2 | N | |

| ∆Val and MRel with MNov | 0.09 | 1.98 | 2,41 | 0.151 | 0.09 | 45 |

| (MRel with) MNov | 0.39 | 12.92 | 2,41 | 0.000 | 0.39 | 45 |

| MNov | 25.91 | 1,42 | 0.000 | 0.38 | 45 | |

| ∆Val and MRel | 0.09 | 2.09 | 2,41 | 0.136 | 0.09 | 45 |

| ∆Val | 4.23 | 1,43 | 0.046 | 0.09 | 45 | |

| Robot vs. Writing on: | ||||||

| V | F | df1,2 | P | ηp2 | n | |

| ∆Val and MRel with MNov | 0.09 | 1.32 | 2,27 | 0.285 | 0.09 | 31 |

| (MRel with) MNov | 0.38 | 8.33 | 2,27 | 0.002 | 0.37 | 31 |

| MNov | 15.40 | 1,28 | 0.001 | 0.36 | 31 | |

| Robot vs. Writing on: | ||||||

| V | F | df1,2 | p | ηp2 | N | |

| ∆ValP vs. ∆ValN | 0.05 | 2.02 | 1,42 | 0.162 | 0.05 | 45 |

| ∆ValP vs. ∆ValN with MRel | 0.02 | 0.71 | 1,42 | 0.406 | 0.02 | 45 |

| ∆ValP vs. ∆ValN with MNov | 0.00 | 0.004 | 1,42 | 0.951 | 0.00 | 45 |

| ∆ValP ∪ ∆ValN with MRel | 3.79 | 1,42 | 0.058 | 0.08 | 45 | |

| ∆ValP ∪ ∆ValN with MNov | 2.04 | 1,42 | 0.161 | 0.05 | 45 | |

| ∆ValP ∪ ∆ValN | 4.23 | 1,43 | 0.046 | 0.09 | 45 | |

| Robot vs. Writing on: | ||||||

| V | F | df1,2 | p | ηp2 | n | |

| ∆ValP vs. ∆ValN | 0.09 | 2.63 | 1,28 | 0.116 | 0.09 | 31 |

| ∆ValP vs. ∆ValN with MRel | 0.01 | 0.30 | 1,28 | 0.588 | 0.01 | 31 |

| ∆ValP vs. ∆ValN with MNov | 0.004 | 0.13 | 1,28 | 0.725 | 0.004 | 31 |

| ∆ValP ∪ ∆ValN | 3.14 | 1,28 | 0.087 | 0.10 | 31 | |

| Variables | Robot | Writing | ||||

| Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | |

| ∆Val | 2.74 | 0.83 | 12 | 1.56 | 0.84 | 11 |

| ∆ValP | 2.68 | 0.84 | 12 | 1.31 | 1.16 | 11 |

| ∆ValN | 2.79 | 0.96 | 12 | 1.77 | 0.75 | 11 |

| MRel | 4.17 | 1.04 | 12 | 4.25 | 1.31 | 11 |

| MNov | 3.27 | 0.92 | 12 | 4.52 | 0.56 | 11 |

| With emotional outliers: n = 23 | ||||||

| Variables | Robot | Writing | ||||

| Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | |

| ∆Val | 2.65 | 0.80 | 10 | 1.69 | 0.83 | 7 |

| ∆ValP | 2.55 | 0.81 | 10 | 1.42 | 1.21 | 7 |

| ∆ValN | 2.75 | 0.95 | 10 | 1.96 | 0.78 | 7 |

| MRel | 4.13 | 0.80 | 10 | 1.70 | 0.83 | 7 |

| MNov | 3.45 | 1.02 | 10 | 4.49 | 0.64 | 7 |

| Without emotional outliers: n = 17 | ||||||

| Robot vs. Writing on: | ||||||

| V | F | df1,2 | P | ηp2 | n (outliers included) | |

| ∆Val and MRel with MNov | 0.46 | 8.09 | 2,19 | 0.003 | 0.46 | 23 |

| ∆Val | 8.80 | 1,20 | 0.008 | 0.31 | 23 | |

| MRel | 2.16 | 1,20 | 0.160 | 0.10 | 23 | |

| (MRel with) MNov | 0.47 | 8.42 | 2,19 | 0.002 | 0.47 | 23 |

| ∆Val with MNov | <1 | 2,19 | 0.459 | 23 | ||

| ∆Val and MRel | 0.40 | 6.79 | 2,20 | 0.006 | 0.40 | 23 |

| ∆Val | 11.51 | 1,21 | 0.003 | 0.35 | 23 | |

| MRel | 0.03 | 1,21 | 0.867 | 0.001 | 23 | |

| Robot vs. Writing on: | ||||||

| V | F | df1,2 | P | ηp2 | n (outliers excluded) | |

| ∆Val and MRel with MNov | 0.38 | 3.94 | 2,13 | 0.046 | 0.38 | 17 |

| ∆Val | 4.07 | 1,14 | 0.063 | 0.23 | 17 | |

| MRel | 2.23 | 1,14 | 0.157 | 0.14 | 17 | |

| (MRel with) MNov | 0.44 | 5.16 | 2,13 | 0.022 | 0.44 | 17 |

| MNov | 10.87 | 1,14 | 0.005 | 0.44 | 17 | |

| (∆Val with) MNov | 0.15 | 1,14 | 0.700 | 0.01 | 17 | |

| ∆Val and MRel | 0.30 | 3.04 | 2,14 | 0.080 | 0.30 | 17 |

| ∆Val | 5.64 | 1,15 | 0.031 | 0.27 | 17 | |

| MRel | 0.074 | 1,15 | 0.790 | 0.005 | 17 | |

| Robot vs. Writing on: | ||||||

| V | F | df1,2 | p | ηp2 | n | |

| ∆ValP vs. ∆ValN | 0.04 | 0.78 | 1,20 | 0.387 | 0.04 | 23 |

| ∆ValP vs. ∆ValN with MRel | 0.003 | 0.06 | 1,20 | 0.815 | 0.003 | 23 |

| ∆ValP ∪ ∆ValN | 13.54 | 1,20 | 0.001 | 0.40 | 23 | |

| Robot vs. Writing on: | ||||||

| V | F | df1,2 | p | ηp2 | n | |

| ∆ValP vs. ∆ValN | 0.03 | 0.48 | 1,14 | 0.498 | 0.033 | 17 |

| ∆ValP vs. ∆ValN with MRel | 0.00 | 0.06 | 1,14 | 0.936 | 0.000 | 17 |

| ∆ValP ∪ ∆ValN | 5.98 | 1,14 | 0.028 | 0.30 | 17 | |

| ∆ValP vs. ∆ValN with MNov | 0.011 | 0.16 | 1,14 | 0.695 | 0.011 | 17 |

| ∆ValP ∪ ∆ValN | 4.07 | 1,14 | 0.063 | 0.23 | 17 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duan, Y.; Yoon, M.; Liang, Z.; Hoorn, J.F. Self-Disclosure to a Robot: Only for Those Who Suffer the Most. Robotics 2021, 10, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics10030098

Duan Y, Yoon M, Liang Z, Hoorn JF. Self-Disclosure to a Robot: Only for Those Who Suffer the Most. Robotics. 2021; 10(3):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics10030098

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuan, Yunfei (Euphie), Myung (Ji) Yoon, Zhixuan (Edison) Liang, and Johan Ferdinand Hoorn. 2021. "Self-Disclosure to a Robot: Only for Those Who Suffer the Most" Robotics 10, no. 3: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics10030098

APA StyleDuan, Y., Yoon, M., Liang, Z., & Hoorn, J. F. (2021). Self-Disclosure to a Robot: Only for Those Who Suffer the Most. Robotics, 10(3), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics10030098