Interactive Maps for the Production of Knowledge and the Promotion of Participation from the Perspective of Communication, Journalism, and Digital Humanities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Maps as Instruments of Multimedia Digital Social Communication

2.2. The Digital Humanities and the New Paradigms of Knowledge Production from the History of Communication

3. Objectives and Methods

4. Theoretical Model for the Conceptualization and Design of Interactive Digital Maps for the Production of Knowledge and Participation

4.1. Interactive Maps and Knowledge Production

- Knowledge decentralization. Decentralizing knowledge means showing the social reality, moving away from the traditional order in which the places where the centers of power are located determine the explanation of what happens within the whole territory to the plurality of men and women that make up the social body. This avoids androcentric, ethnocentric, Eurocentric, urbancentric orders, etc. At each node of the global society (understood as a place—city, village, or neighborhood—in which communication and transport networks converge), social processes occur differently. At each one, people in different situations coexist for reasons of gender, origin, social position, age, etc., whose experiences differ from others. This must lead to a rethinking of the traditional hierarchical ordering of knowledge, which is possible through maps complemented with other interactive and participatory resources. The reading of an interactive map does not have an established order, since each person can choose the starting point according to their interests, as well as the order in which they consult other elements.

- Pluralization of social knowledge. In a plural networked society, users have equally plural and situated knowledge. Only by considering the plurality of social experiences is it possible to understand the complexity of today’s societies. Thus, it is necessary to see that in addition to the decentralization of knowledge, it is necessary to give voice to the different social experiences, which are complex and in continuous interaction, and that are found in the physical spaces that make up the fabric of the networked society. In 2008, the historian Mercedes Vilanova formulated the Galileo conjecture in these terms: “History will be explained as a network of relationships, and the fragmented narratives that began in prehistory will defeat the state and universal histories that were possible as a result of writing” [66]. In the same article, the author states that the digital revolution will make this process inevitable and uncontrollable, and under a state of constant renewal, making the official memories, that is, the social discourses dominant until now, cease to be the absolute referents. Maps contribute to this change by allowing different voices to be presented in a geolocated complementary way such that a dialogue is established that makes similarities and differences visible in order to establish dialogic and deliberative processes in order to base social participation through knowledge and respect.

- The reticularization of knowledge. Reticularization breaks with the traditional schema of historical and social explanations based on the idea of nation, region, or locality as socio-political units built independently. Instead, it shows how the past and the present are the result of the interactions that occur between people and groups who exchange products and knowledge using the transport and communication systems present in each location and in each era. As a consequence of the decentralization and pluralization of knowledge, it is also possible to geolocate expert and non-expert knowledge, experiential or personal, offering situated explanations that gather together the whole of the social experience in dialogue and showing how networks structure social activity.

- Humanization of information and knowledge. Human quality information is that which is produced considering that citizens, as members of society, need useful information for every aspect of their life, and to be able to contribute their knowledge, experiences, and expectations. Moreno et al. [67] established five criteria to build information with human quality to promote participation, which we share as essential elements for the paradigm shift we propose. These criteria are: (I) the humanization of information, presenting citizens as protagonists of information and social events and avoiding depersonalization; (II) complete and transparent information; (III) contextualized information with memory; (IV) verified and verifiable information; and (V) understandable information.

4.2. Maps as Instruments to Promote Political and Social Participation

- Egalitarianism. Everyone must be able to participate by contributing knowledge, social experience, and expectations and, therefore, considering that each is the carrier of relevant knowledge and experiences for others. This entails upsetting the traditional knowledge hierarchies that rank people according to their knowledge in certain fields, excluding groups due to gender, origin, academic training, etc.

- Horizontality. Interactive maps allow contributions to be published by geolocating and structuring them, using chronological and thematic parameters that order them based on variable selection criteria, that is, chosen by each user and avoiding univocal hierarchies. The thematic criteria should be organized in such a way that they avoid the traditional logics that prioritize public events led by people, generally men, who occupy the centers of power and the places and spaces where they carry out these activities [62]. This thematization must show the relationship between personal stories and collective history, considering the pluralities present in contemporary societies to ensure that personal contributions are coordinated with each other and with expert contributions in order to avoid being anecdotal. This requires an effort to reorganize thought and traditional academic categories.

- Criticism. Interactive digital maps form part of the so-called civic technologies, which are used by social organizations as digital strategies to promote political participation in public institutions in order to strengthen democracy [24]. These tools allow a wide range of policies along with the management of public resources to be controlled and monitored, highlighting transparency as one of the key issues [68]. Producing a critical map involves conceiving it through collaborative parameters to create representations appropriate to the interests of the participants.

4.3. Maps as Instruments for the Visualization of Data That Favors the User Experience

- Interactivity. Online digital maps can be static when they are simple cartographic images, or interactive when they allow users to use selection, configuration, presentation, or other options to offer layers of information or improve the user experience with other accessories. The natural space for interactive maps is the Internet and online publications, which allow these options to be used in real time and with updated information.

- Multimediality. Interactive digital maps are multimedia products in their own right. However, they can also be complemented with other multimedia resources that can be accessed through the map to offer information in textual or audiovisual format.

- Reticularity of reading. As previously discussed, mapped spatial information offers a non-linear, reticular reading. This point, already discussed, is included here because it is also an element related to the experience of the user, who can choose the reading paths according to personal criteria.

- Participation. The interactive digital multimedia maps that we propose must offer the chance to participate in the construction of information in a collaborative and participatory way, both among experts and through receiving the contributions of any citizen. The development of the possibilities of Web2.0 enables the inclusion of different types of tools to incorporate these contributions, publishing these contents not as isolated units but as elements that complement each other and provide feedback.

5. Cases: The Mapa Infoparticipa and the Ciutadania Plural Platform

5.1. The Mapa Infoparticipa

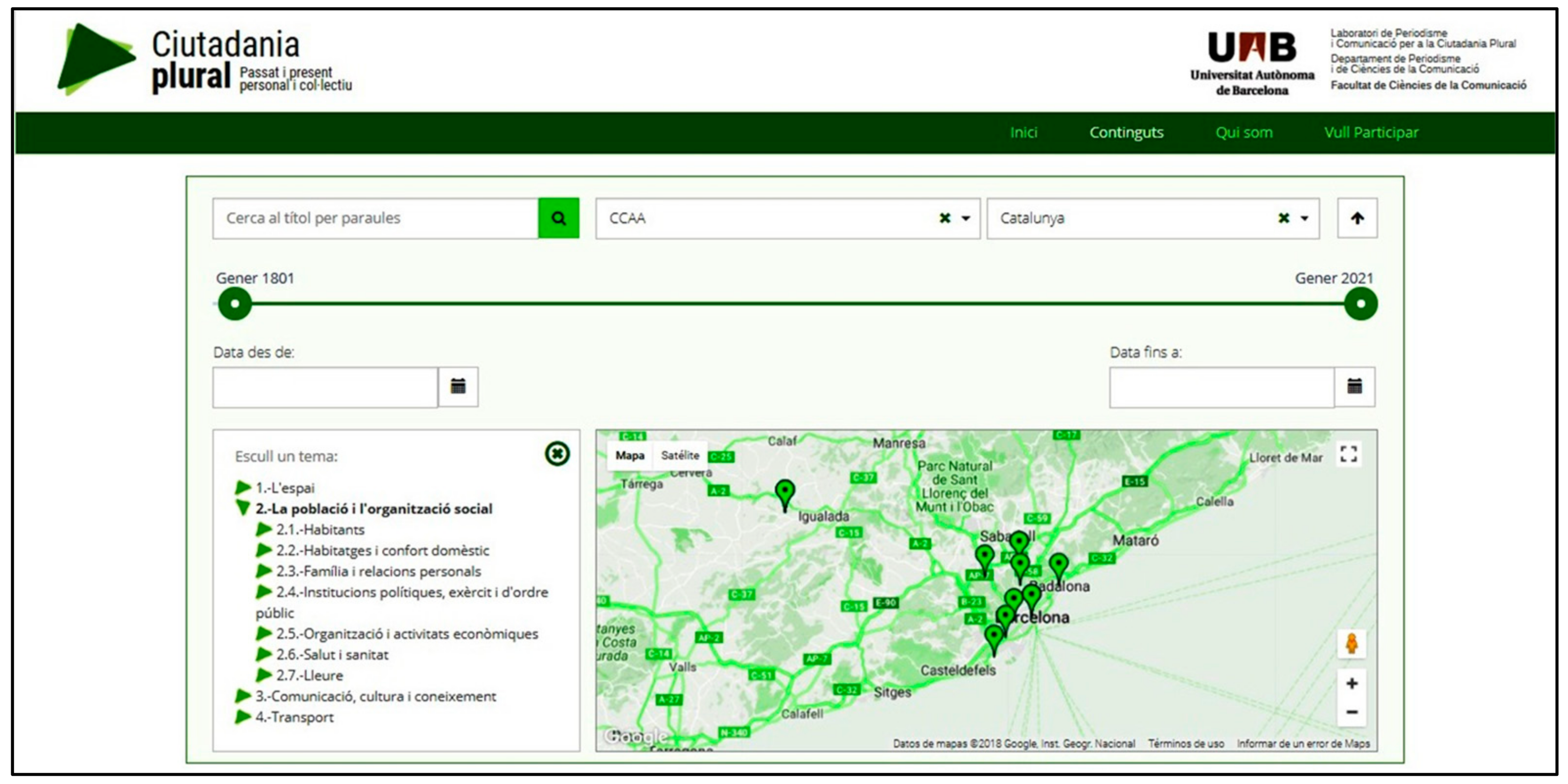

5.2. The Ciutadania Plural Platform

6. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perceval, J.M. Historia Mundial de la Comunicación; Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 2015; p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Buisseret, D. La Revolución Cartográfica en Europa. La Representación de Nuevos Mundos en la Europa del Renacimiento; Paidos: Barcelona, Spain, 2004; pp. 1400–1800. [Google Scholar]

- Monmonier, M.S. Drawing the Line: Tales of Maps and Cartocontroversy; Henry Holt: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Koyre, A. Del Mundo Cerrado al Universo Infinito; Siglo XXI: Madrid, Spain, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Todorov, T. Nous et les Autres; Seuil: Paris, France, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, J.B. Hacia una deconstrucción del Mapa. In La Nueva Naturaleza de los Mapas; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2005; pp. 185–207. Available online: http://148.202.18.157/sitios/catedrasnacionales/material/2010a/luis_cabrales/2.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Mezzadra, S.; Neilson, B. La Frontera Como Método; Traficantes de sueños: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo, J.J. Neofascismo y Religión. Los Predficadores del Odio. In Neofascismo. La Liberal; Siglo XXI: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- López Borrego, R. Estética del Viaje. Reflexiones en Torno al arte y el Nomadismo Global; Amarante: Salamanca, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Flórez, F. Mierda y Catástrofe. Síndromes Culturales del Arte Contemporáneo; Fórcola: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- LabComPublica. Laboratorio de Periodismo y Comunicación para la Ciudadanía Plural (n.d.). Mapa Infoparticipa. Available online: https://www.mapainfoparticipa.com/index/mapa (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- LabComPublica. Laboratorio de Periodismo y Comunicación para la Ciudadanía Plural (n.d.). Ciutadanía Plural. Available online: http://www.ciutadaniaplural.com/#/home (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Link, E.; Henke, J.; Möhring, W. Credibility and Enjoyment through Data? Effects of Statistical Information and Data Visualizations on Message Credibility and Reading Experience. J. Stud. 2021, 22, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, J.; Hanham, J.; Meier, P. The Internet explosion, digital media principles and implications to communicate effectively in the digital space. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2018, 15, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, J.L. La Infografía. Técnicas, Análisis y Usos Periodísticos; Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sarın, P.; Uluğtekin, N. Analyzing Newspaper Maps for Earthquake News through Cartographic Approach. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López Linares, C. ¿Cómo pueden los mapas ayudar a los periodistas a narrar mejor sus historias? Fundación Gabo. 2021. Available online: https://fundaciongabo.org/es/blog/laboratorios-periodismo-innovador/como-pueden-los-mapas-ayudar-los-periodistas-narrar-mejor-sus (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Canter, L. It’s not all cat videos. Digit. J. 2018, 6, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, M.; Rodríguez, M.P.; Díaz de Guereñu, J.M. Journalism in the age of hybridization: Los vagabundos de la chatarra—comics journalism, data, maps and advocacy. Catalan J. Commun. Cult. Stud. 2018, 10, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrondo Ureta, A.; Ferreras Rodríguez, E.M. The potential of investigative data journalism to reshape professional culture and values. Study Bellwether Transnatl. Projects. Commun. Soc. 2021, 34, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Zuo, L. The Inapplicability of Objectivity: Understanding the Work of Data Journalism. Journal. Pract. 2021, 15, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalph, F. Classifying Data Journalism. Journal. Pract. 2018, 12, 1332–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparici, R.; García-Marín, D. Prosumers and emirecs: Analysis of two confronted theories. Comunicar 2018, 55, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez Duarte, J.M.; Bolaños Huertas, M.V.; Magallón Rosa, R.; Caffarena, V.A. El papel de las tecnologías cívicas en la redefinición de la esfera pública. Hist. Y Comun. Soc. 2015, 20, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roth, R.E. Cartographic Design as Visual Storytelling: Synthesi and Review of Map-Based Narratives, Genres, and Tropes. Cartogr. J. 2021, 58, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, C. Intercreatividad y Web 2.0. La construcción de un cerebro digital planetario. In Planeta Web 2.0. Inteligencia Colectiva o Medios Fast Food. Barcelona/México DF: Grup de Recerca d’Interaccions Digitals; Cobo, C., Hugo, P., Eds.; Universitat de Vic: Barcelona, Spain; pp. 43–60.

- Moon, M.J. The Evolution of E-Government among Municipalities: Rhetoric or Reality? Public Adm. Rev. 2002, 62, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, E.W.; Hinnant, C.C.; Moon, M.J. Linking Citizen Satisfaction with E-Government and Trust in Government. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2005, 15, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez Mellado, J.A.; Torres Manjón, J. Redes geosociales: Una Web cercana, cartográfica y de sensaciones, realizada por todos y basada en el geoconocimiento colectivo. In Tecnologías de la Información geográfica: La Información Geográfica al Servicio de los Ciudadanos; Ojeda, J., Pita, M.F., Vallejo, I., Eds.; Secretariado de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2010; pp. 1369–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D. Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Buzai, G.D. Geografía y tecnologías digitales del siglo XXI: Una aproximación a las nuevas visiones del mundo y sus impactos científicos-tecnológicos. Scr. Nova 2004, 8, 170. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-170-58.htm (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Capel, H. Geografía en red a comienzos del Tercer Milenio. Por una ciencia solidaria y en colaboración. Scr. Nova. Rev. Electrónica De Geogr. Y Cienc. Soc. 2010, XIV, 313. Available online: http.://www.ub.es/geocrit/sn/sn-313.htm (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Bates, D. The political theology of entropy: A Katechon for the cybernetic age. Hist. Hum. Sci. 2020, 33, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afanador, M.J. Tecnología al servicio de las humanidades. Telos 2019, 112, 66–71. Available online: https://telos.fundaciontelefonica.com/telos-112-cuaderno-central-humanidades-en-un-mundo-stem-maria-jose-afanadortecnologia-al-servicio-de-las-humanidades (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Vinck, D. Humanidades Digitales: La Cultura Frente a Las Nuevas Tecnologías; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://elibro.net/es/ereader/uab/118568?page=86 (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Oropesa Serrano, M.C.; Rodríguez Roche, S. Digital Humanities: Analysis of Research carried out in the Faculty of Communication in the Period 1993–2016. Cienc. De La Inf. 2017, 48, 9–14. Available online: http://content.ebscohost.com/ContentServer.asp?EbscoContent=dGJyMNXb4kSep7U4y9fwOLCmsEmep7RSsKi4S7OWxWXS&ContentCustomer=dGJyMPPX4FPr1%2BeGudvii9%2Fm5wAA&T=P&P=AN&S=R&D=asn&K=128141659 (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Thomas, W.G. Computing and the Historical Imagination. In A Companion to Digital Humanities; Schreibman, S., Siemens, R., Unsworth, J., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig, R. Scarcity or Abundance? Preserving the Past in a Digital Era. Am. Hist. Rev. 2003, 108, 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnton, R. The New Age of the Book. New York Rev. Books 1999, 46, 5–7. Available online: https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1999/03/18/the-new-age-of-the-book/ (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Del Río, G. La mirada humana, la mirada crítica. Telos 2019, 112, 50–55. Available online: https://telos.fundaciontelefonica.com/telos-112-cuaderno-central-humanidades-en-un-mundo-stem-gimena-del-rio-la-mirada-humana-la-mirada-critica/ (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Rodríguez Ortega, N. Humanidades digitales, poshumanidad y neohumnismo. Telos 2019, 112, 58–65. Available online: https://telos.fundaciontelefonica.com/telos-112-cuaderno-central-humanidades-en-un-mundo-stem-nuria-rodriguez-humanidades-digitales-poshumanidad-y-neohumanismo/ (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Ethington., P.J. Los Angeles and the Problem of Urban Historical Knowledge. Am. Hist. Rev. 2000, 105, 1667. Available online: https://chnm.gmu.edu/digitalhistory/links/cached/introduction/link0.23.LAurbanhistoricalknowledge.html (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Habegger, S.; Mancila, I. El Poder de la Cartografía Social en las Prácticas Contrahegemónicas o la Cartografía Social Como estrategia Para Diagnosticar Nuestro Territorio. Available online: http://www.beu.extension.unicen.edu.ar/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/365/Habegger%20y%20Mancila_El%20poder%20de%20la%20cartografia%20social.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Klonner, C.; Hartmann, M.; Dischl, R.; Djami, L.; Anderson, L.; Raifer, M.; Lima-Silva, F.; Castro Degrossi, L.; Zipf, A.; Porto de Albuquerque, J. The Sketch Map Tool Facilitates the Assessment of OpenStreetMap Data for Participatory Mapping. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J. Evaluation Methods for Citizen Design Science Studies: How Do Planners and Citizens Obtain Relevant Information from Map-Based E-Participation Tools? ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampermann, A.; Opdenakker, R.; Heijden, B.; Bücker, J. Intercultural Competencies for Fostering Technology-Mediated Collaboration in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radil, S.M.; Anderson, M.B. Rethinking PGIS: Participatory or (post)political GIS? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 43, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B. Constructing community through maps? Power and praxis in community mapping. Prof. Geogr. 2006, 58, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, R. Public-participation GIS. In The International Encyclopedia of Geography; Richardson, D., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Radil, S.; Jiao, J. Public participatory GIS and the geography of inclusion. Prof. Geogr. 2016, 68, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, K.; Baud, I.; Denis, E.; Scott, D.; Sydenstricker-Neto, J. Participatory spatial knowledge management tools: Empowerment and upscaling or exclusion? Inf. Commun. Soc. 2013, 16, 258–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. Public participation GIS (PPGIS) for regional and environmental planning: Reflections of a decade of empirical research. URISA J. 2012, 25, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Public participation in the Geoweb era: Defining a typology for geo-participation in local governments. Cities 2019, 85, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, R.E.; Robinson, P.J.; Johnson, P.A.; Corbett, J.M. Doing public participation on the geospatial web. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2016, 106, 1030–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.Y.; Brudney, J.L.; Jakobsen, M.; Andersen, S.C. Coproduction of government services and the new information technology: Investigating the distributional biases. Public Ad-Minist. Rev. 2013, 73, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.; Dunham, J.M. Volunteered geographic information, urban forests, & envi-ronmental justice. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2014, 53, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Brabham, D.C. Crowdsourcing the public participation process for planning projects. Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Kyttä, M. Key issues and research priorities for public participation GIS (PPGIS): A synthesis based on empirical research. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 46, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, B. Little boxes, glocalization, and networked individualism. In Digital Cities II: Computational and Sociological Approaches; Tanabe, M., van den Besselaar, P., Ishida, T., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 2362, pp. 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Sardà, A. El Arquetipo Viril Protagonista de la Historia. Ejercicios de Lectura No-androcéntrica; LaSal: Barcelona, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Sardà, A. La Otra ‘Política’ de Aristóteles. Cultura de Masas y Divulgación del Arquetipo Viril; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Sardà, A. De qué Hablamos cuando Hablamos del Hombre. Treinta Años de Crítica y Alternativas al Pensamiento Androcéntrico; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Esteve, A.; Zueras, P. El equipo del Explorador Social. Explorador Social: El dato hecho realidad. Perspect. Demogr. 2021, 23, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardà, A.M.; De Barcelona, U.A.; Rodríguez-Navas, P.M.; Solà, N.S. CiudadaniaPlural.com: From Digital Humanities to Plural Humanism. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2017, 72, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berners, T.; Fischetti, M. Weaving the Web: The Original Design and Ultimate Destiny of the World Wide Web by Its Inventor; Texere: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vilanova, M. Trabajos por hacer: Cuatro conjeturas. Hist. Antropol. Y Fuentes Orales 2008, 39, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sardá, A.M.; Rodríguez-Navas, P.M.; Rius, M.C.; Pérez, A.A.; Farran, M.B. Infoparticip@: Periodismo para la participación ciudadana en el control democrático. Criterios, metodologías y herramientas. Estud. Sobre El Mensaje Periodis. 2013, 19, 783–803. Available online: http://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/ESMP/article/view/43471 (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Skaržauskienė, A.; Mačiulienė, M. Mapping International Civic Technologies Platforms. Informatics 2020, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amparo, M.S.; Pedro, M.R.-N.; Núria, S.S. The impact of legislation on the transparency in information published by local administrations [El impacto de la legislación sobre transparencia en la información publicada por las administraciones locales]. El Prof. De La Inf. 2017, 26, 370–380. Available online: https://www.elprofesionaldelainformacion.com/contenidos/2017/may/03.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Rodríguez-Navas, P.M.; Morales, N.J.M. The Transparency of Ecuadorians municipal websites: Methodology and results [La transparencia de los municipios de Ecuador en sus sitios web: Metodología y resultados]. Am. Lat. Hoy 2018, 80, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López López, P.C.; Márquez Domínguez, C.; Molina Rodríguez-Navas, P.; Ramos Gil, Y.T. Transparency and public information in the Ecuadorian television: Ecuavisa and TC Televisión cases. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2018, 73, 1307–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudt, W.R.; Medranda Morales, N.; Sánchez Montoya, R. Evaluation of transparency of public information on Canadian mining projects in Ecuador. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo Flórez, J.A. Historia digital: La memoria en el archivo infinito. Hist. Crit. 2011, 43, 82–103. Available online: https://revistas.uniandes.e (accessed on 1 July 2021). [CrossRef]

| Area | Principles |

|---|---|

| I. Interactive maps and knowledge production | Decentralization Pluralization Reticularization Humanization |

| II. Maps as instruments to promote political and social participation | Egalitarianism Horizontality Criticism |

| III. Maps as instruments for the visualization of data that favors the user experience | Interactivity Multimediality Reticularity of reading Participation |

| (I) Interactive maps and knowledge production | |

| Decentralization | The map presents a main page depending on the country from which it is consulted. Selection tools for searches by municipality, region or autonomous community, country and other territorial entities, different public administrations, or private entities. Geolocalization of the information. |

| Pluralization | Selection tools for searches according to characteristics of the institutions, such as the gender of the mayor, the political party in government, or territorial entities such as the number of inhabitants. Language selection tools. |

| Reticularization | Cooperative production through the use of a content manager that allows teams located in different cities and countries to work. Possibilities of consultation and comparison between different types of territorial, administrative, or political units. |

| Humanization | Open publication of the evaluation methodology and results in a complete, transparent, easily understandable, accessible and verifiable way for anyone: formulation of the evaluation indicators in question form; calculation of results considering the same value for each indicator to facilitate understanding. Publication of context data for each unit analyzed and the history of annual evaluations carried out to provide information with memory and context. |

| (II) Maps as instruments to promote political and social participation | |

| Egalitarianism | The evaluation indicators are agreed with representatives of public institutions, municipal entities, communication professionals and academia. Tools for anyone to submit suggestions. |

| Horizontality | Presentation of expert knowledge geolocated on the map. |

| Criticism | Identification of the results on the map through colors to easily identify the good and bad practices of the administrations or organizations analyzed. Publication of results reports on the same platform, highlighting both successes and shortcomings. |

| (III) Maps as instruments for the visualization of data that favours the user experience | |

| Interactivity | Query selection tools and levels of content depth. |

| Multimediality | A map complemented with infographic and textual elements. |

| Reticularity of reading | A map without linear or hierarchical order of reading. |

| Participation | Expert participation in the conceptualization of the procedure and possibilities for consultation and dialogue with the management team. |

| (I) Interactive maps and knowledge production | |

| Decentralization | Selection by locality, region, nation, or other demarcations or through thematic or chronological queries that relate places. |

| Pluralization | Theming that relates personal stories to collective history. Anyone can make textual or audiovisual contributions. |

| Reticularization | Presentation of the present and past relationships between people through thematic tags and georeferenced identifiers. |

| Humanization | Geographic, chronological, and thematic selection. Organization of the information in articles or documents constructed journalistically to facilitate understanding and reading. Grouping of complementary articles in stories. |

| (II) Maps as instruments to promote political and social participation | |

| Egalitarianism | Anyone can complement the expert information with stories and images of their experiences, presenting themselves as an active social subject. |

| Horizontality | The participatory contributions are located in their thematic, chronological and geographical scope, together with the expert contributions. |

| Criticism | Theming that breaks with traditional androcentric schemes, presenting social reality as a result of the decisions and activities of all people. |

| (III) Maps as instruments for the visualization of data that favours the user experience | |

| Interactivity | Through query tools. |

| Multimediality | Use of videos, images, audios, infographics, etc. as an alternative to the text or as a complement, both in expert documents and in personal contributions. |

| Reticularity of reading | Selections read on the map. Understanding of historical thematic relationships thanks to geolocation. |

| Participation | Anyone can publish their contributions in text or image format by registering on the platform and using the participation tools. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molina Rodríguez-Navas, P.; Muñoz Lalinde, J.; Medranda Morales, N. Interactive Maps for the Production of Knowledge and the Promotion of Participation from the Perspective of Communication, Journalism, and Digital Humanities. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10110722

Molina Rodríguez-Navas P, Muñoz Lalinde J, Medranda Morales N. Interactive Maps for the Production of Knowledge and the Promotion of Participation from the Perspective of Communication, Journalism, and Digital Humanities. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2021; 10(11):722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10110722

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolina Rodríguez-Navas, Pedro, Johamna Muñoz Lalinde, and Narcisa Medranda Morales. 2021. "Interactive Maps for the Production of Knowledge and the Promotion of Participation from the Perspective of Communication, Journalism, and Digital Humanities" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 10, no. 11: 722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10110722

APA StyleMolina Rodríguez-Navas, P., Muñoz Lalinde, J., & Medranda Morales, N. (2021). Interactive Maps for the Production of Knowledge and the Promotion of Participation from the Perspective of Communication, Journalism, and Digital Humanities. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 10(11), 722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10110722