Self-Organizing Maps to Evaluate Multidimensional Trajectories of Shrinkage in Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. State of the Art

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data

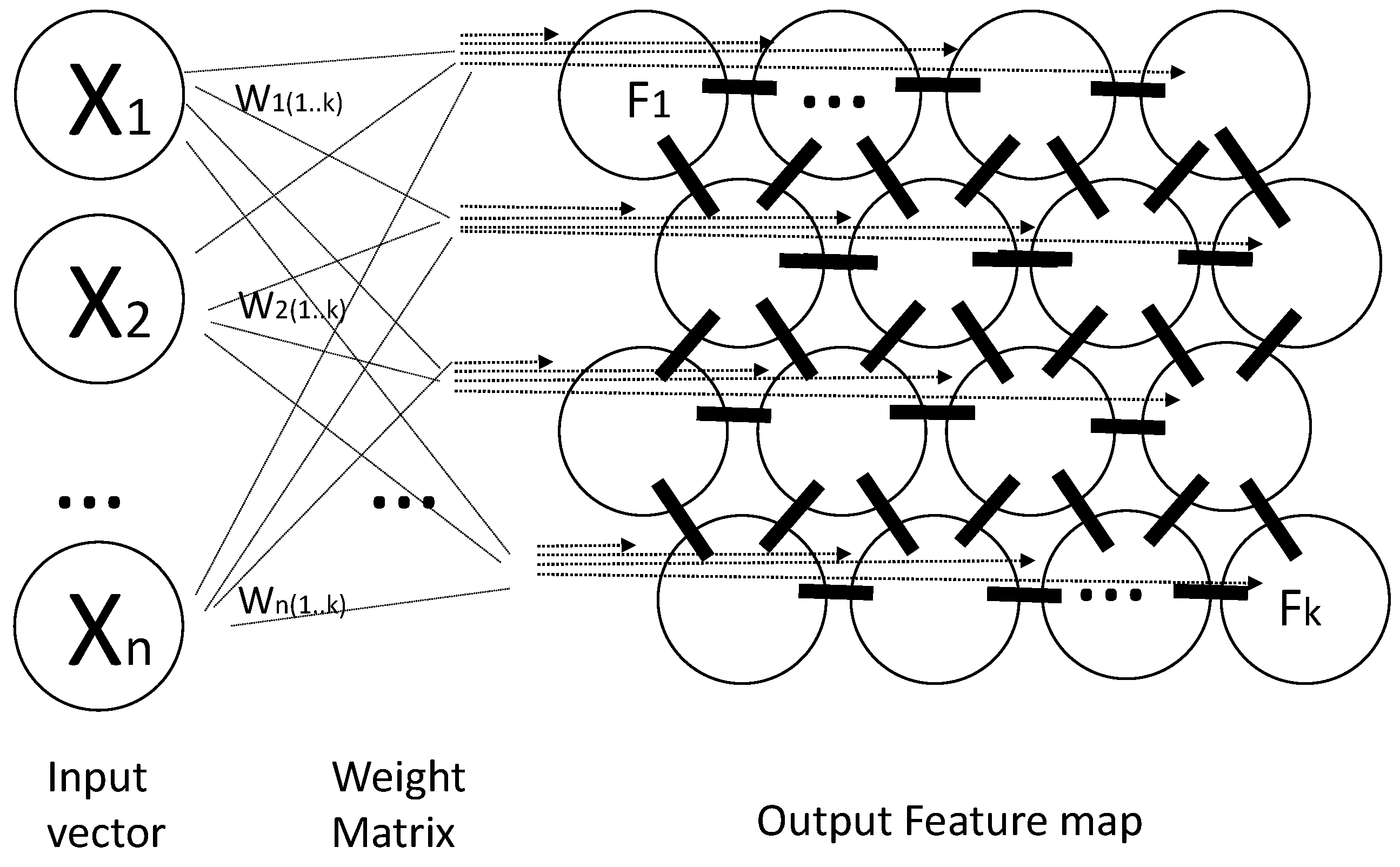

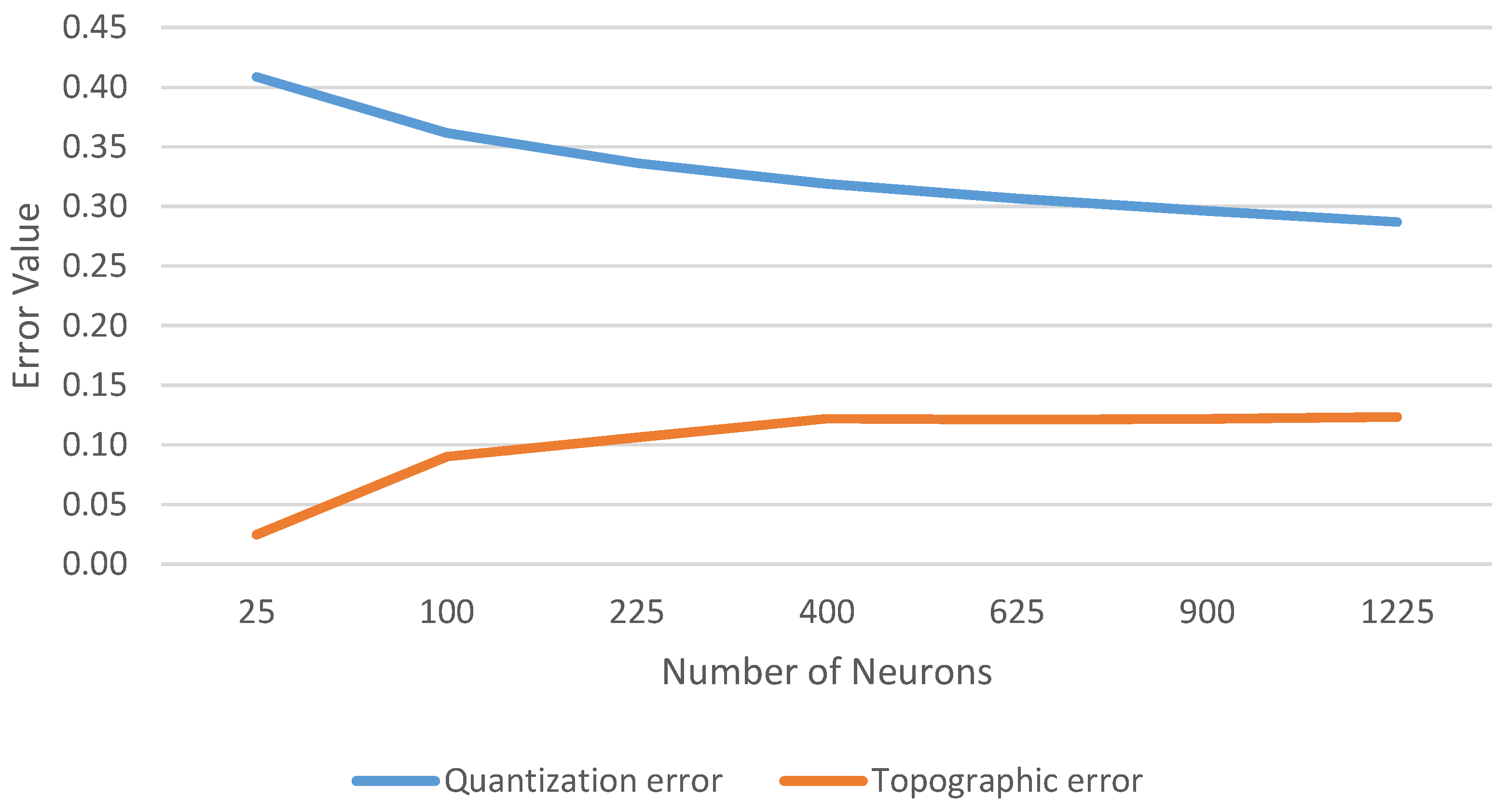

3.3. Methodology

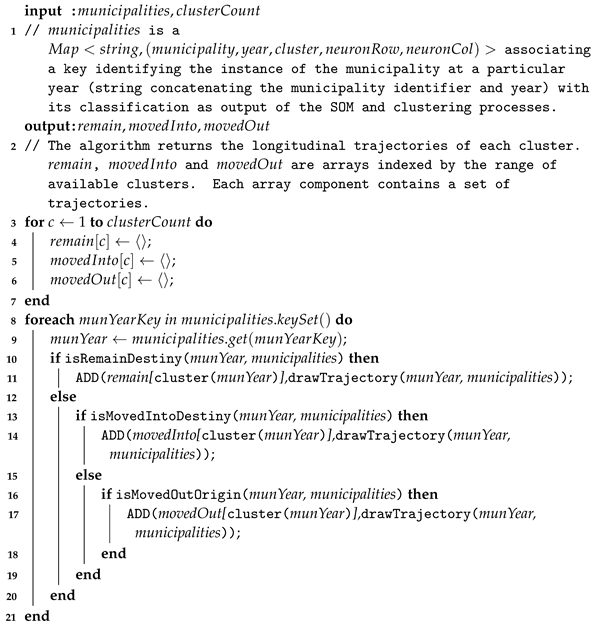

| Algorithm 1: Generation of longitudinal trajectories |

|

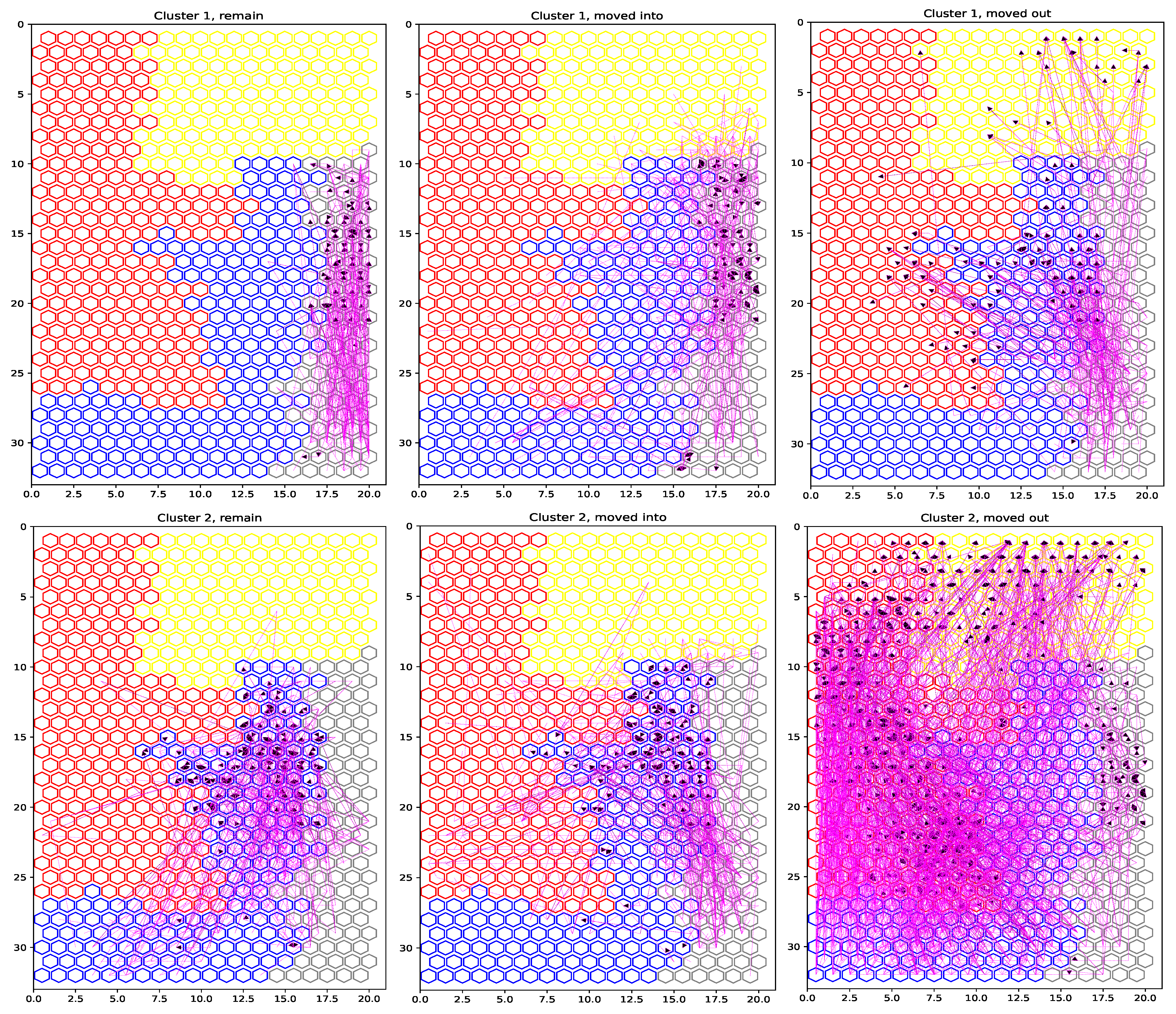

4. Results

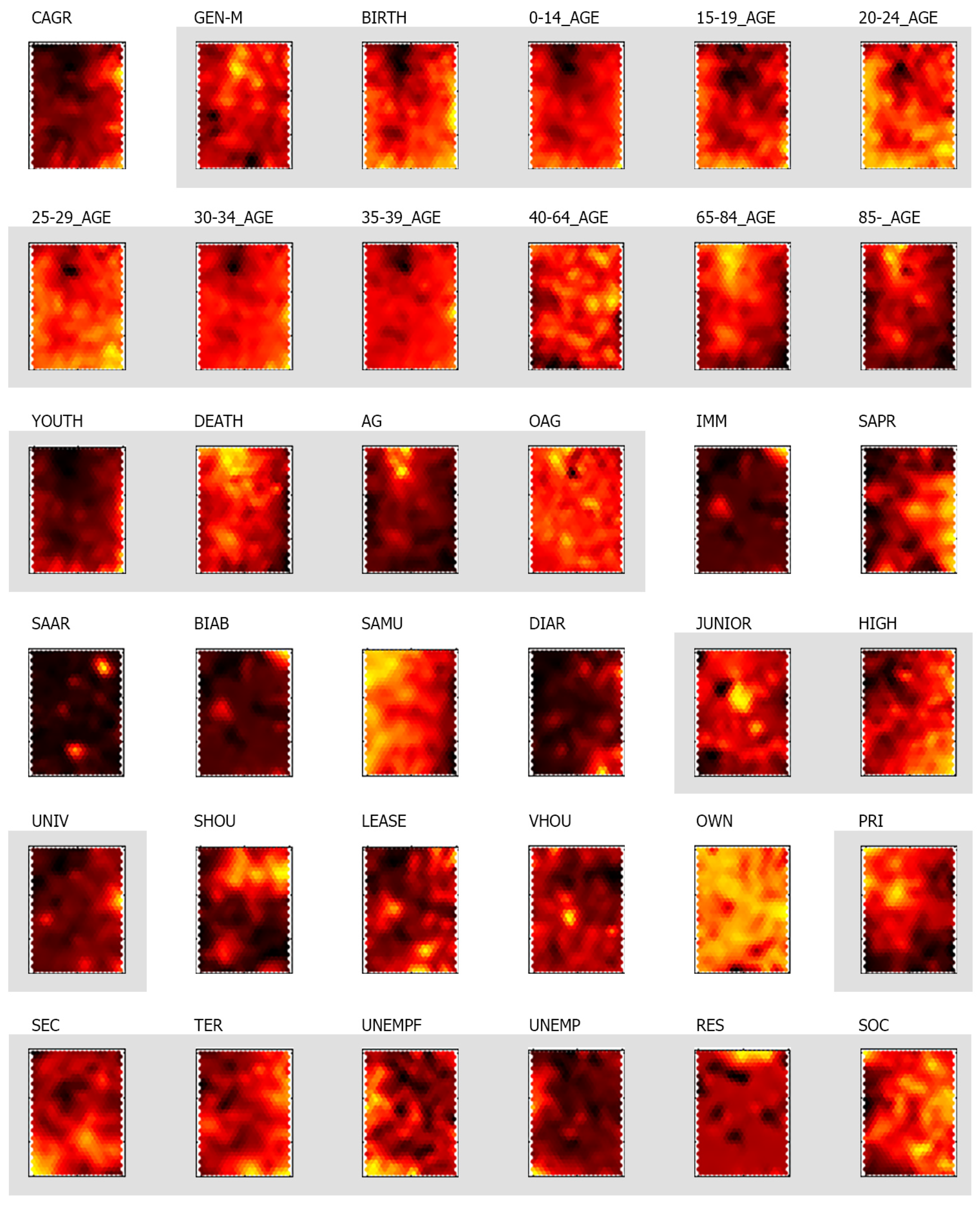

4.1. Feature Weights and Component Planes

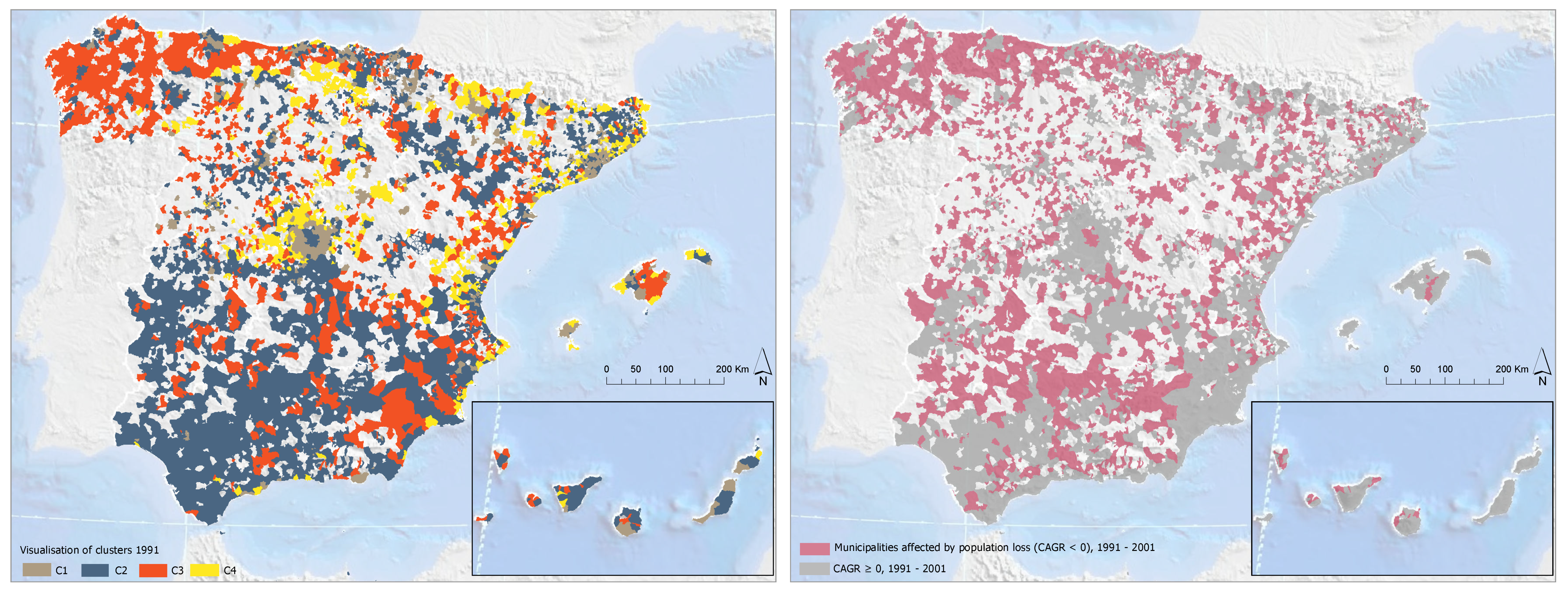

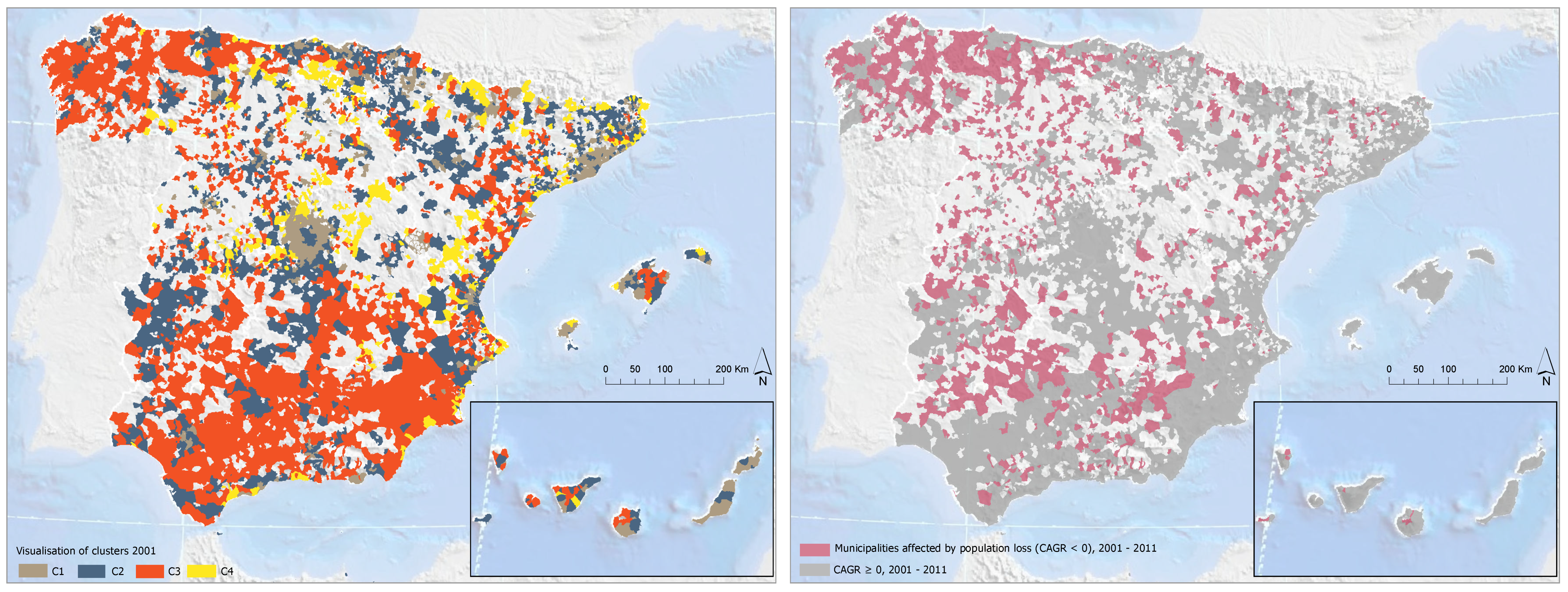

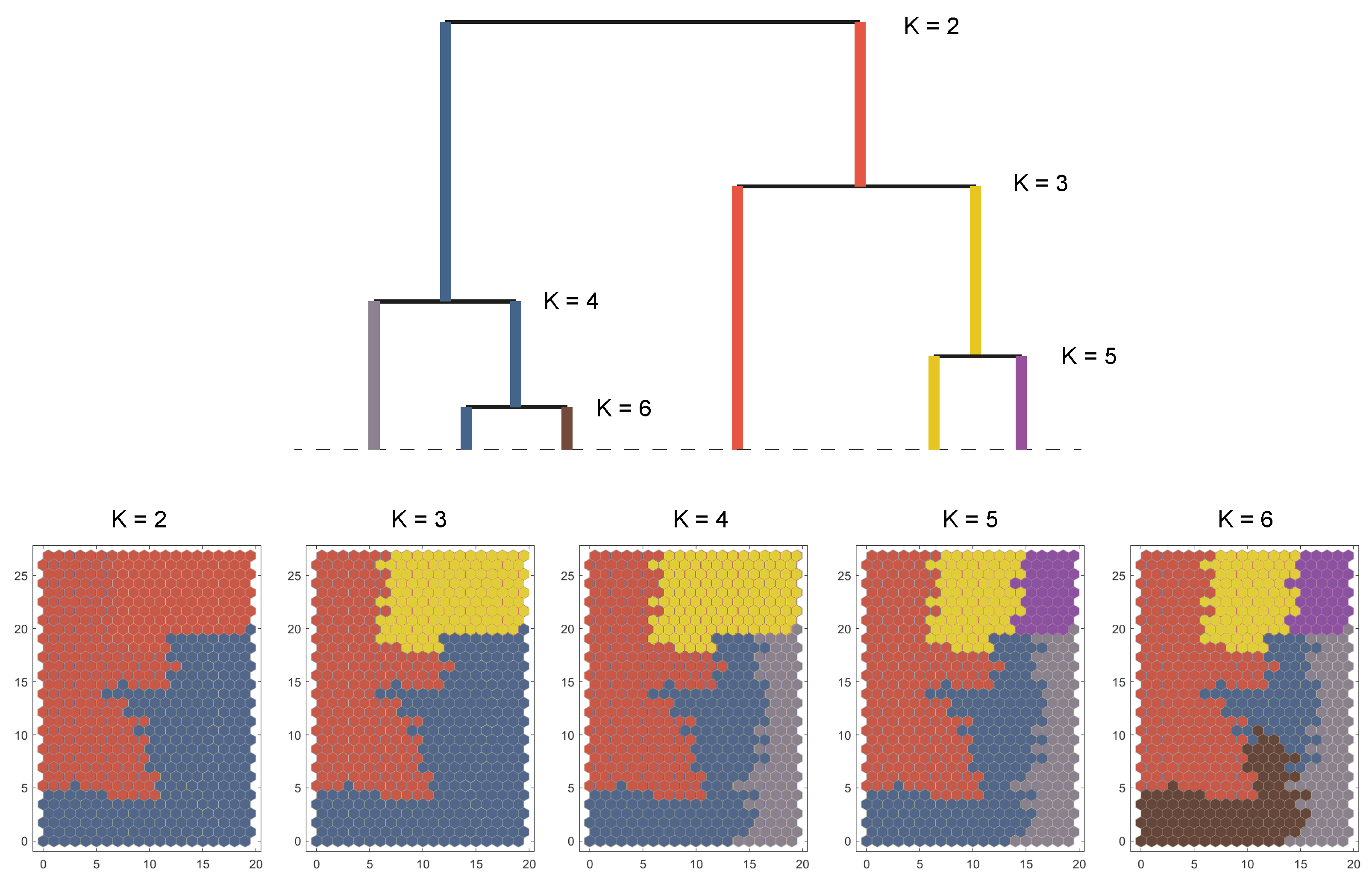

4.2. Cluster Characterization and Geographic Distribution of Shrinkage

- Cluster 1 (low shrinkage, positive CAGR: 0.026): The municipalities in this cluster reveal high values with respect to the birth rate, the youth index, the percentage of people in their thirties, the percentage of people who graduated from high school and university, the socioeconomic condition, and the tertiary activity rate. In addition, this cluster holds the highest percentage of people living in a province or region different from the one corresponding to their birth place (SAPR and DIAR). Last, this cluster shows low values with respect to the aging index, the death index, the unemployment rate, and the primary activity rate.

- Cluster 2 (middle shrinkage, stagnant CAGR: 0.007): This cluster holds median values with respect to the birth rate, the youth index, the percentage of people living in the same province as the one corresponding to their birth place, the aging index, and the death index. The cluster is also characterized by low values regarding the percentage of foreign people and the lowest values for the second housing rate. Last, this cluster shows average socioeconomic condition scores slightly lower than those of other clusters (specially for cluster 1 and 4), and high secondary activity and unemployment rates.

- Cluster 3 (high shrinkage, negative CAGR: −0.010): This cluster holds low values with respect to the birth rate and the youth index. In addition, the cluster has the lowest values regarding the restoration activity, the socioeconomic condition, the leased housing rates, and the percentage of people who graduated from high school and university. On the contrary, this cluster is characterized by the highest values with respect to the primary activity, the unemployment rate for people who are looking for their first employment, and the percentage of people living in the same municipality as their birth place. Last, the cluster also shows high values for the death rate and the aging index.

- Cluster 4 (middle shrinkage, stagnant CAGR: 0.001): This cluster is characterized by the lowest values of the birth rate and the youth index. It also has the lowest values regarding the vacant housing and the unemployment rates. In addition, the cluster holds median values with respect to the tertiary activity (similar to cluster 2). Last, it must be noted that this cluster holds the highest values concerning the death rate, the aging index, the percentage of foreign people, the secondary housing rate, the restoration activity, and the percentage of people living in the same region as the one corresponding to their birth place.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Beauregard, R.A. Urban Population Loss in Historical Perspective: United States, 1820–2000. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2009, 41, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Großmann, K.; Bontje, M.; Haase, A.; Mykhnenko, V. Shrinking cities: Notes for the further research agenda. Cities 2013, 35, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallagst, K. Shrinking Cities; Planning Challenges from an International Perspective. Urban Infill Themenh.—Cities Grow. Smaller 2008, 10, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z.; Jin, L.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, H. Characteristics and influences of urban shrinkage in the exo-urbanization area of the Pearl River Delta, China. Cities 2020, 103, 102767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswalt, P.; Rieniets, T.E. Atlas of Shrinking Cities; Hatje Cantz: Berlin, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Fernández, C.; Audirac, I.; Fol, S.; Cunningham-Sabot, E. Shrinking Cities: Urban Challenges of Globalization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, D.; Barreira, A.P.; Guimarães, M.H.; Panagopoulos, T. Historical trajectories of currently shrinking Portuguese cities: A typology of urban shrinkage. Cities 2016, 52, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hattori, K.; Kaido, K.; Matsuyuki, M. The development of urban shrinkage discourse and policy response in Japan. Cities 2017, 69, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musterd, S.; Bontje, M. Understanding shrinkage in European regions. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 196–213. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, A.; Rink, D.; Grossmann, K.; Bernt, M.; Mykhnenko, V. Conceptualizing Urban Shrinkage. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2014, 46, 1519–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turok, I.; Mykhnenko, V. The trajectories of European cities, 1960–2005. Cities 2007, 24, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.; Haase, D.; Haase, A. Compact or spread? A quantitative spatial model of urban areas in Europe since 1990. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, M.; Fol, S.; Roth, H.; Cunningham-Sabot, E. Shrinking cities: Measuring the phenomenon in France. Cybergeo Eur. J. Geogr. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.; Wiechmann, T. Urban growth and decline: Europe’s shrinking cities in a comparative perspective 1990–2010. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2018, 25, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lo, K.; Zhang, P. Population shrinkage in resource-dependent cities in China: Processes, patterns and drivers. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Segers, T.; Devisch, O.; Herssens, J.; Vanrie, J. Conceptualizing demographic shrinkage in a growing region—Creating opportunities for spatial practice. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 195, 103711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moral, S.; Méndez, R.; Prada, J. El fenómeno de las ’shrinking cities’ en España: Una aproximación a las causas, efectos y estrategias de revitalización a través del caso de estudio de Avilés. In New Trends in the XXIst Century Spanish Geography. Contribución española al 32º Congreso de la Unión Geográfica Internacional; Raitt, D.I., Ed.; International Geographical Union: Cologne, Germany, 2012; pp. 252–266. [Google Scholar]

- Kohonen, T. Self-Organizing Maps; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson, B.C. Climate analysis, modelling, and regional downscaling using self-organizing maps. In Self-Organising Maps: Applications in Geographic Information Science; Agarwal, P., Skupin, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 137–163. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Sun, G.; Yang, C.; Liang, K.; Ma, S.; Huang, L. Using self-organizing map for coastal water quality classification: Towards a better understanding of patterns and processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628, 1446–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skupin, A.; Hagelman, R. Visualizing demographic trajectories with self-organizing maps. GeoInformatica 2005, 9, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, R.; Bação, F.; Lobo, V. Carto-SOM: Cartogram creation using self-organizing maps. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2009, 23, 483–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrienko, G.; Andrienko, N.; Demsar, U.; Dransch, D.; Dykes, J.; Fabrikant, S.I.; Jern, M.; Kraak, M.J.; Schumann, H.; Tominski, C. Space, time and visual analytics. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 1577–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henriques, R.; Bacao, F.; Lobo, V. Exploratory geospatial data analysis using the GeoSOM suite. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2012, 36, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmelle, E.; Thill, J.C.; Furuseth, O.; Ludden, T. Trajectories of multidimensional neighbourhood quality of life change. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 923–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenauer, J.; Helbich, M. Hierarchical self-organizing maps for clustering spatiotemporal data. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2013, 27, 2026–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wu, X.; Ge, J.; Liu, F.; Zhao, W.; Wu, C. Influence of mining activities on groundwater hydrochemistry and heavy metal migration using a self-organizing map (SOM). J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Rustum, R.; Shankar, V.; Adeloye, A.J. Self-organizing map estimator for the crop water stress index. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Bank Open Data; Technical Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, L.; Poelman, H.; Veneri, P. The EU-OECD definition of a functional urban area. In OECD Regional Development Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019; Volume 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Skupin, A. Self-Organising Maps: Applications in Geographic Information Science; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas-Bel, D.; Schmidt, C.R. Self-organizing maps and the US urban spatial structure. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2013, 40, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmelle, E.C.; Haslauer, E.; Prinz, T. Social satisfaction, commuting and neighborhoods. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 30, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahegan, M.; Takatsuka, M.; Wheeler, M.; Hardisty, F. Introducing GeoVISTA Studio: An integrated suite of visualization and computational methods for exploration and knowledge construction in geography. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2002, 26, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pölzlbauer, G. Survey and Comparison of Quality Measures for Self-Organizing Maps. In Proceedings of the 5th Workshop Data Analysis, Erice, Italy, 27 October–3 November 2004; Elfa Academic: Press, Slovakia, 2004; pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Breard, G.T. Evaluating self-Organizing Map Quality Measures as Convergence Criteria. Master’s Thesis, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vesanto, J.; Himberg, J.; Alhoniemi, E.; Parhankangas, J. SOM Toolbox for Matlab 5; Technical Report; Citeseer: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vesanto, J.; Alhoniemi, E. Clustering of the self-organizing map. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2000, 11, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, S.; Shamsuddin, S.M. Multistrategy self-organizing map learning for classification problems. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2011, 2011, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohonen, T. MATLAB Implementations and Applications of the Self-Organizing Map; Unigrafia Oy: Helsinki, Finland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Batagelj, V. Generalized Ward and related clustering problems. In Classification and Related Methods of Data Analysis; Bock, H.H., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wiechmann, T.; Wolff, M. Urban Shrinkage in a Spatial Perspective—Operationalization of Shrinking Cities in Europe 1990–2010. In Proceedings of the AESOP-ACSP Joint Congress, Dublin, Ireland, 15–19 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nelle, A.; Großmann, K.; Haase, D.; Sigrun Kabisch, D.R.; Wolff, M. Urban shrinkage in Germany: An entangled web of conditions, debates and policies. Cities 2017, 66, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | n | Label | Variable | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population change | 1 | CAGR | Compound annual growth rate | e.g., |

| Demography | 2 | GEN-M | Gender | Male/total population |

| 3 | BIRTH | Birth rate | Number of births in a year with respect to total population | |

| 4 | 0–14_AGE | Age structure | Persons 14/total population | |

| 5 | 15–19_AGE | Persons 15–19/total population | ||

| 6 | 20–24_AGE | Persons 20–24/total population | ||

| 7 | 25–29_AGE | Persons 25–29/total population | ||

| 8 | 30–34_AGE | Persons 30–34/total population | ||

| 9 | 35–39_AGE | Persons 35–39/total population | ||

| 10 | 40–64_AGE | Persons 40–64/total population | ||

| 11 | 65–84_AGE | Persons 65–84/total population | ||

| 12 | 85–_AGE | Persons 85/total population | ||

| 13 | YOUTH | Youth index | Population under 15 years old/population over 65 years old | |

| 14 | DEATH | Death rate | Number of deaths in a year with respect to total population | |

| 15 | AG | Aging index | Population above 85 years old/0–19 population | |

| 16 | OAG | Over-aging index | Population above 85 years old/ population above 65 years old | |

| Mobility | 17 | IMM | Foreign immigrants | Persons/total population |

| 18 | SAPR | Living in the same province they were born in | Persons/total population | |

| 19 | SAAR | Living in the same autonomous regions they were born in | Persons/total population | |

| 20 | BIAB | Born abroad | Persons/total population | |

| 21 | SAMU | Living in the same municipality they were born in | Persons/total population | |

| 22 | DIAR | Living in a different autonomous region from where they were born | Persons/total population | |

| Education | 23 | JUNIOR | Graduate from elementary, junior high school | Graduated above 15 years old/persons above 15 years old |

| 24 | HIGH | Graduate from high school | Graduated above 15 years old/persons above 15 years old | |

| 25 | UNIV | Graduate from college, university | Graduated above 15 years old/persons above 15 years old | |

| Housing | 26 | SHOU | Second housing rate | Second housing/total housing |

| 27 | LEASE | Leased housing rate | Leased housing/total housing | |

| 28 | VHOU | Vacant housing rate | Vacant housing/total housing | |

| 29 | OWN | Owned housing rate | Household/total housing | |

| Economy | 30 | PRI | Primary industry rate | Persons above 15 years old in primary industry sector/persons above 15 years old |

| 31 | SEC | Secondary industry rate | Persons above 15 years old in secondary industry sector/persons above 15 years old | |

| 32 | TER | Tertiary industry rate | Persons above 15 years old in tertiary industry sector/persons above 15 years old | |

| 33 | UNEMPF | Unemployment (looking for first employment) | Unemployed persons above 15 years old/persons above 15 years old | |

| 34 | UNEMP | Unemployment | Unemployed persons above 15 years old/persons above 15 years old | |

| 35 | RES | Restoration activity | Persons above 15 years old in restoration activity/persons above 15 years old | |

| 36 | SOC | Average socioeconomic condition | Arithmetic mean of categorized values from qualitative occupation, activity, and professional situation variables |

| Variable | Variance | C1 (n = 92) | C2 (n = 190) | C3 (n = 228) | C4 (n = 130) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAMU | 0.0270 | 0.2683 | 0.5046 | 0.6670 | 0.5097 |

| SHOU | 0.0259 | 0.1998 | 0.1834 | 0.2138 | 0.5199 |

| SAPR | 0.0154 | 0.5369 | 0.3771 | 0.2540 | 0.2997 |

| PRI | 0.0097 | 0.1539 | 0.1836 | 0.3586 | 0.3116 |

| TER | 0.0060 | 0.5693 | 0.4603 | 0.3793 | 0.4583 |

| x65_84_AGE | 0.0045 | 0.1765 | 0.2393 | 0.3038 | 0.3266 |

| DIAR | 0.0042 | 0.2568 | 0.1526 | 0.0997 | 0.1794 |

| 35_39_AGE | 0.0034 | 0.5028 | 0.4271 | 0.3826 | 0.3741 |

| SEC | 0.0031 | 0.3823 | 0.4567 | 0.3542 | 0.3266 |

| UNIV | 0.0029 | 0.3240 | 0.2406 | 0.1967 | 0.2250 |

| RES | 0.0025 | 0.3261 | 0.3240 | 0.3003 | 0.4160 |

| SOC | 0.0020 | 0.4599 | 0.3866 | 0.3543 | 0.4185 |

| BIRTH | 0.0011 | 0.1949 | 0.1646 | 0.1342 | 0.1177 |

| YOUTH | 0.0010 | 0.1198 | 0.0765 | 0.0537 | 0.0467 |

| JUNIOR | 0.0010 | 0.3575 | 0.3792 | 0.4161 | 0.4281 |

| HIGH | 0.0009 | 0.2887 | 0.2559 | 0.2140 | 0.2422 |

| VHOU | 0.0009 | 0.1622 | 0.1771 | 0.1957 | 0.1235 |

| 85-_AGE | 0.0006 | 0.0695 | 0.0938 | 0.1192 | 0.1261 |

| CAGR | 0.0004 | 0.3595 | 0.3266 | 0.3085 | 0.3214 |

| IMM | 0.0003 | 0.1364 | 0.1205 | 0.1159 | 0.1601 |

| BIAB | 0.0003 | 0.1511 | 0.1305 | 0.1250 | 0.1685 |

| UNEMP | 0.0003 | 0.2543 | 0.2711 | 0.2708 | 0.2293 |

| SAAR | 0.0003 | 0.0585 | 0.0685 | 0.0605 | 0.0982 |

| LEASE | 0.0003 | 0.1508 | 0.1473 | 0.1118 | 0.1333 |

| x15_19_AGE | 0.0002 | 0.1802 | 0.1756 | 0.1650 | 0.1458 |

| 0_14_AGE | 0.0002 | 0.0990 | 0.0889 | 0.0759 | 0.0649 |

| DEATH | 0.0001 | 0.0473 | 0.0627 | 0.0740 | 0.0761 |

| 20_24_AGE | 0.0001 | 0.2004 | 0.1996 | 0.1927 | 0.1721 |

| 30_34_AGE | 0.0001 | 0.1068 | 0.0925 | 0.0833 | 0.0788 |

| OWN | 0.0001 | 0.8108 | 0.7910 | 0.8184 | 0.8005 |

| 25_29_AGE | 0.0001 | 0.1353 | 0.1270 | 0.1195 | 0.1088 |

| GEN_M | 0.0001 | 0.4751 | 0.4718 | 0.4735 | 0.4951 |

| AG | 0.0000 | 0.0135 | 0.0181 | 0.0242 | 0.0330 |

| UNEMPF | 0.0000 | 0.0638 | 0.0721 | 0.0732 | 0.0555 |

| OAG | 0.0000 | 0.3370 | 0.3412 | 0.3478 | 0.3348 |

| 40_64_AGE | 0.0000 | 0.1995 | 0.1954 | 0.1969 | 0.2026 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz-Varona, A.; Lacasta, J.; Nogueras-Iso, J. Self-Organizing Maps to Evaluate Multidimensional Trajectories of Shrinkage in Spain. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11020077

Ruiz-Varona A, Lacasta J, Nogueras-Iso J. Self-Organizing Maps to Evaluate Multidimensional Trajectories of Shrinkage in Spain. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2022; 11(2):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11020077

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-Varona, Ana, Javier Lacasta, and Javier Nogueras-Iso. 2022. "Self-Organizing Maps to Evaluate Multidimensional Trajectories of Shrinkage in Spain" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 11, no. 2: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11020077

APA StyleRuiz-Varona, A., Lacasta, J., & Nogueras-Iso, J. (2022). Self-Organizing Maps to Evaluate Multidimensional Trajectories of Shrinkage in Spain. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 11(2), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11020077