1. Introduction

Tell me how come there’s so much guns in the street an’ none a dem gun neva mek ya?

—Morgan Heritage, Tell Me How Come.

The question posed above by reggae musicians Morgan Heritage centers around why there are so many guns in Jamaica—a country that is not a recognized gun manufacturer—and the related crimes that come with their presence. Questions such as these are common in countries across Latin America and the Caribbean Sea, where the rates of violent crime have steadily increased [

1,

2]. In fact, Natarajan [

3] argued that many of the most serious crime problems are now in developing countries, a contrast to the developed countries, where crime rates have declined [

4,

5].

For the most part, however, criminologists and crime scientists, most of whom work in developed/Westernized nations, have paid little attention to this problem [

3] (although see Shenderovich et al. [

6]). Natarajan’s [

3] observations on the contrasting treatment of crime in the developed versus developing world were contained in a publication among a series that used data from El Salvador [

7,

8], India [

9], Colombia [

10], Brazil [

11,

12], among other developing countries [

13,

14], and gave attention to crime studies and analysis in developing world settings. While Natarajan’s [

3] argument is relevant and timely, criminology in the developing world has not been entirely neglected. Scholars, including Appiahene-Gyamfi [

15,

16,

17], Araujo [

18], Cummings et al. [

19], Pujol-Luz et al. [

20], Reuter and O’Regan [

21], Scabin et al. [

22], Souza et al. [

23], Spiegel et al. [

24], de Melo et al. [

25], and Valente [

26], have examined various aspects of crime in the developing world. In Amazonia, in particular, the struggle over access to natural resources and the resulting tensions that develop from logging, gold mining, cattle farming, and similar activities tend to dominate the discussion around crime [

22]. Beyond simply mapping the cases of deforestation and degradation due to illegal activities, however, there is a growing body of literature aimed at managing crime, albeit those that are environment-related, in various Amazonian settings. A few cases illustrate this point.

First, in addressing the problem of illegal logging in the Anavilhanas National Park, located in the Brazilian state of Amazonas, Scabin et al. [

22] noted that there was a connection between the higher intensity of illegal timber harvesting and human settlements. Secondly, Nepstad et al. [

27] pointed out that the presence of indigenous lands in the Brazilian Amazon served as a barrier to illegal logging. In fact, [

27] pointed out that indigenous territories had similar effects on reducing illegal logging and fire, as has been the case for parks. Thirdly, Spiegel et al. [

24], in responding to the high levels of deforestation attributed to illegal mining, examined how geographic information systems (GIS) and shuttle radar imagery could reduce tensions over areas that have been contested for mining. Spiegel et al. [

24] observed that there is a pressing need for scholars to focus on crimes against the environment or green criminology [

28,

29] and that there is a role for GIS tools in mapping locations of interest. Fourthly, and perhaps most importantly, from the perspective of this paper, Souza et al. [

23] studied the relationships between the various economic processes of territorial occupation in the Amazon and how they influence the spatial diffusion of homicidal violence, the movements of people and merchandise. Grain production as a driver of territorial occupation did not influence the diffusion of homicidal violence, but Souza et al. [

23] reported that the expansion of deforestation and livestock rearing influenced where such violence occurred. These observations appear to go against Weisburd’s [

30] laws of crime concentration, which suggest that crime stays within a narrow bandwidth across time, despite strong volatility in crime incidents. Weisburd focused on micro-places—streets, street segments, and addresses—in developing the law of crime concentration. Whether such observations will hold through for macro-places—states, counties, and countries—remains poorly studied. In Amazonia, high-value resource extraction activities that lead to deforestation have been linked to violent crime, but how these vary across space needs more attention. This paper does not track the causes of violent crime directly but rather seeks to track where such crimes have occurred and how they align with Weisburd’s [

30] law of crime concentration. Of more significant concern to this paper is the fact that most resource extraction activities within Amazonian contexts tend to occur within indigenous peoples-influenced landscapes [

31], and yet, crime’s influence on such landscapes remain unexplored. Examining how Weisburd’s [

30] laws of crime concentration hold to tropical settings can be important for developing crime prevention policy.

As evidence continues to mount that crime across Amazonia is increasing [

32], the implications of such findings for native peoples need urgent attention. Green criminology, environmental crime, or the study of crimes affecting human and non-human life, ecosystems, and the biosphere [

28,

29] provide theoretical lenses for studying such crimes. In the case of Guyana, the area of interest for this study, the last three to four decades have seen a wide and diverse range of crimes occur within its borders. Internationally, the most prominent crime to have occurred in Guyana was the Jonestown massacre in 1978 [

33], while the plot by Guyanese and men of Guyanese ancestry to bomb John F. Kennedy airport [

34] in New York has also gained significant attention. However, the Omai gold mine spill that occurred in Guyana [

35], the largest industrial spill of its kind, was the most prominent environmental incident that could potentially be termed a crime. Apart from environmental crimes, earlier studies have pointed towards an upsurge in violent crime in Guyana [

19]. In fact, in 2010, a report carried in the Stabroek News [

36], one of Guyana’s leading newspapers, pointed out that there was one murder every three days in Guyana, with locations outside of the main municipal centers the site for some of these crimes. Furthermore, the Stabroek News [

37] published reports attributed to the Crime Chief of Guyana, who pointed out that geography and low population density were making tackling crime difficult. Despite the signals that there has been an upsurge in crime in Guyana, little has been done, at least from the perspective of the academic literature, to study crime’s spatial distribution in order to guide policing policy and decision-making processes. A key reason for this lag is that the data on crime are not readily and publically available. This is particularly the case for crimes that are committed within rural settings. Access challenges, and geography, as the Crime Chief put it, may prevent our understanding of the crime landscape and how they relate to Weisburd’s laws of crime concentration.

With the foregoing in mind, this paper takes steps towards understanding how the spatial distribution of crime in Guyana has changed relative to indigenous peoples-influenced landscapes. On the backdrop of Weisburd’s [

30] law of crime concentration, we hypothesize that over the past two decades or so the concentration of crime events shifted away from micro-places. Shifts in the concentration of crime will have implications for crime relative to indigenous peoples-influenced landscapes. Analyzing whether crime spatial distribution relative to indigenous lands has changed can provide insight into where scholars and police alike can focus their efforts on studying crime. In this regard, our paper, drawing on geographical information systems (GIS) methods, pursues two primary goals. First, using unofficial data derived from newspapers, the spatial distribution of violent crime is examined relative to indigenous lands to determine whether crime’s concentration moved away or ‘shifted’ from the urban landscape. Secondly, we examine how the distribution of murders committed using firearms and bladed weapons has changed relative to indigenous peoples’ lands. This latter focus is critical, as violent crime committed with these weapons can have implications for the well-being of indigenous peoples and the wildlife with which they are associated (environmental crime). The movement of guns into the forested landscape may have implications for a host of environmental crime, for example, hunting, the well-being of wildlife, and the security of indigenous peoples. In this regard, our analysis provides the foundation for assessing crimes on the environment, and how crime may play a role in shaping processes within indigenous-influenced landscapes, areas of study that are currently neglected in the developing world. We make observations as to whether Weisburd’s [

30] law of crime concentration may apply to the Guyanese landscape, a country that has a declining population.

3. Results

3.1. The Nature of the Archives

The archives of the Stabroek News from 1986–2010 contained reports for a total of 3407 days (out of a possible 9130 days;

Table 1) or about 37% of the possible days during the study. Our sample varied in terms of the number of days that were available for data collection each year (see

Table 1). As the number of crimes and days reported varied across years, we aggregated the crimes from 1987–1991. While our analysis was completed for five-year intervals, we nevertheless examined each year between 1992 through to 2010 individually in spatial analysis. Even though the archives were written in the respective years under consideration, it was not uncommon to have reports in one year covering crimes committed in a previous year. For example, there were only two crimes covered in 1986, and one of these referred to the tragedy of mass suicide / murder at Jonestown, in the Northwest District of Guyana in 1978. This crime was captured in the archives, even though it did not occur during the time the archives were written. Because the report provided details on an event that occurred outside of our study period, we removed it from further analysis. Reports on crimes that occurred after 1986 but were referenced in a subsequent year were included in our analysis, with the crime being attributed to the year in which it occurred. For example, in June 2006, the newspaper reported the results of a murder trial that began in 1998. As the time that the murder was committed was not contained in the archives, this event was captured and attributed to 1998. For our analysis and data collection, the details provided in the 2006 report were used to understand the nature of the event on the day it occurred in 1998. It was not uncommon for cases like these to lack locational information, and hence, mapping them was not possible, but they provided important context in helping to understand the changing crime landscape in Guyana.

Of the days reported on in the archives, a total of 5992 independent crimes, both violent and non-violent, were reported. Violent crimes, including murders, robberies, sexual assault, and common assault with a weapon, amounted to 3943 crimes, or 65.8% of all crimes reported in the archives from 1986–2010. Robberies dominated the sample, accounting for 31.1% of violent crime and 20.5% of all crimes. Murders were the next most frequently reported crime, accounting for 27% of violent crime and 17.8% of all crimes. Assaults that were committed with a weapon, including stabbing with bladed weapons, wounding with clubs, sticks, fists, chemicals, and common weapons, accounted for 28.3% of violent crimes and 18.6% of all crimes. Sexual assault, including rape, indecent assault, and carnal knowledge, accounted for 8.49% of violent crimes and 5.6% of all crimes.

3.2. Locational Data and Mapping Crimes

As mentioned in the Methods section, location data were not available for all crimes. While a total of 5992 crimes were found in the archives, locational data to allow for the mapping of each crime were only available for 5504 events. Overall, the data in the archives were mapped for 1502 distinct locations across the Guyanese landscape. In some instances, the location of the crime provided was very general; for example, “Georgetown”. In such cases, we used the context provided in the news report to place the crime to the nearest known location. Crimes reported in Georgetown, for example, were given the location contained in the gazetteer for Georgetown. In other cases, such as the crime being committed at the “Mashramani Road Jam”, the article did not provide enough details for us to locate the crime. Mashramani is the annual celebration of Guyana becoming a Republic (23 February 1966), and major celebrations take place in Georgetown, New Amsterdam, and Linden. As there were three possible locations where this crime may have been committed, this crime was not mapped. We also made a note of crimes that were committed on Guyanese territory off the terrestrial area of Guyana, in particular cases of piracy in the Atlantic Ocean. In the case of such crimes, though, it was difficult to map these, as descriptions of location may have included, “25 miles off Shell Beach” and “29 nautical miles east of the Waini River”. While Shell Beach and the Waini River are known physical features to the authors, the places themselves cover a wide area. Therefore, the description of 25 miles off Shell beach or 29 nautical miles east of the Waini River did not provide enough detail for us to place these crimes on the map.

3.3. General Distribution of Crime

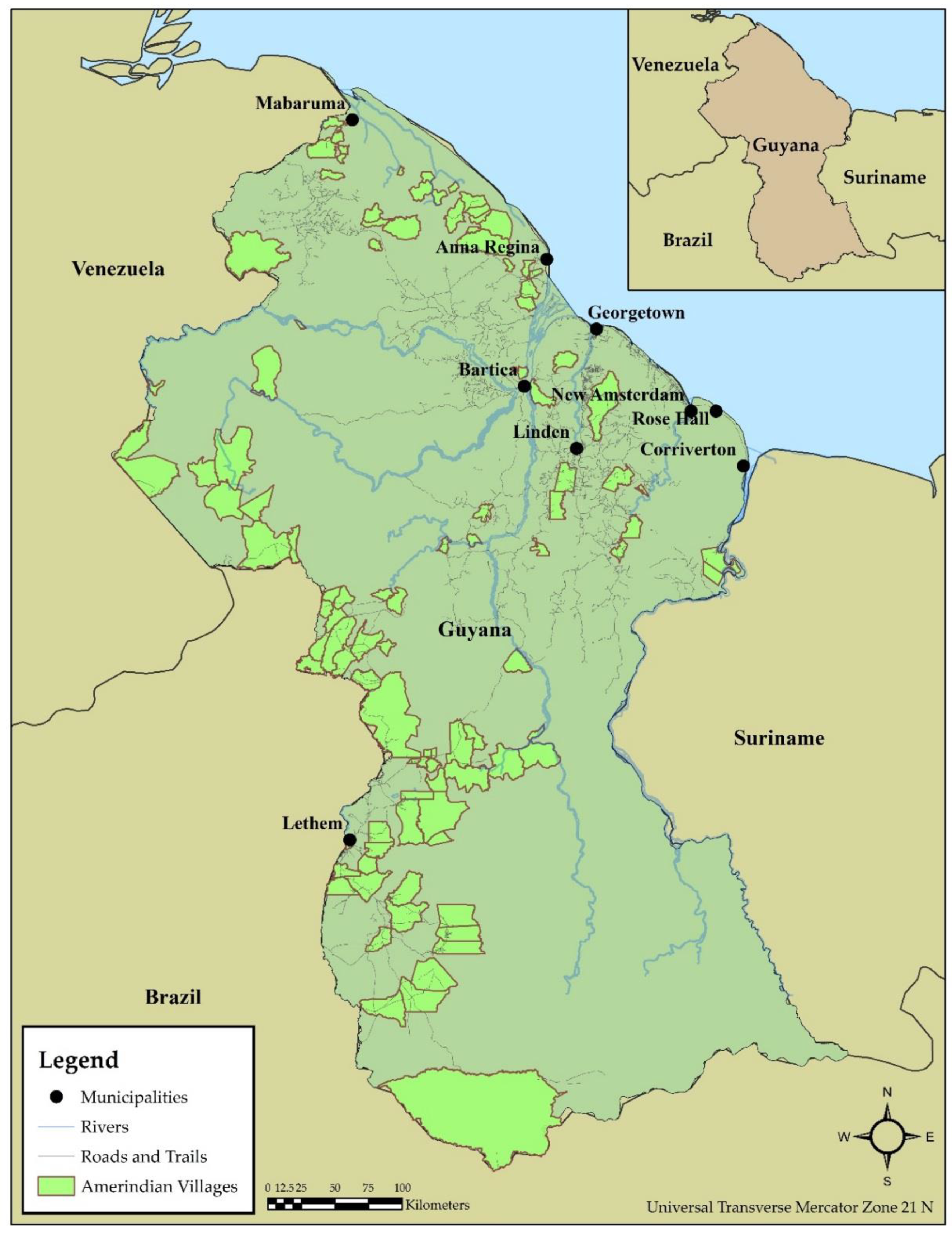

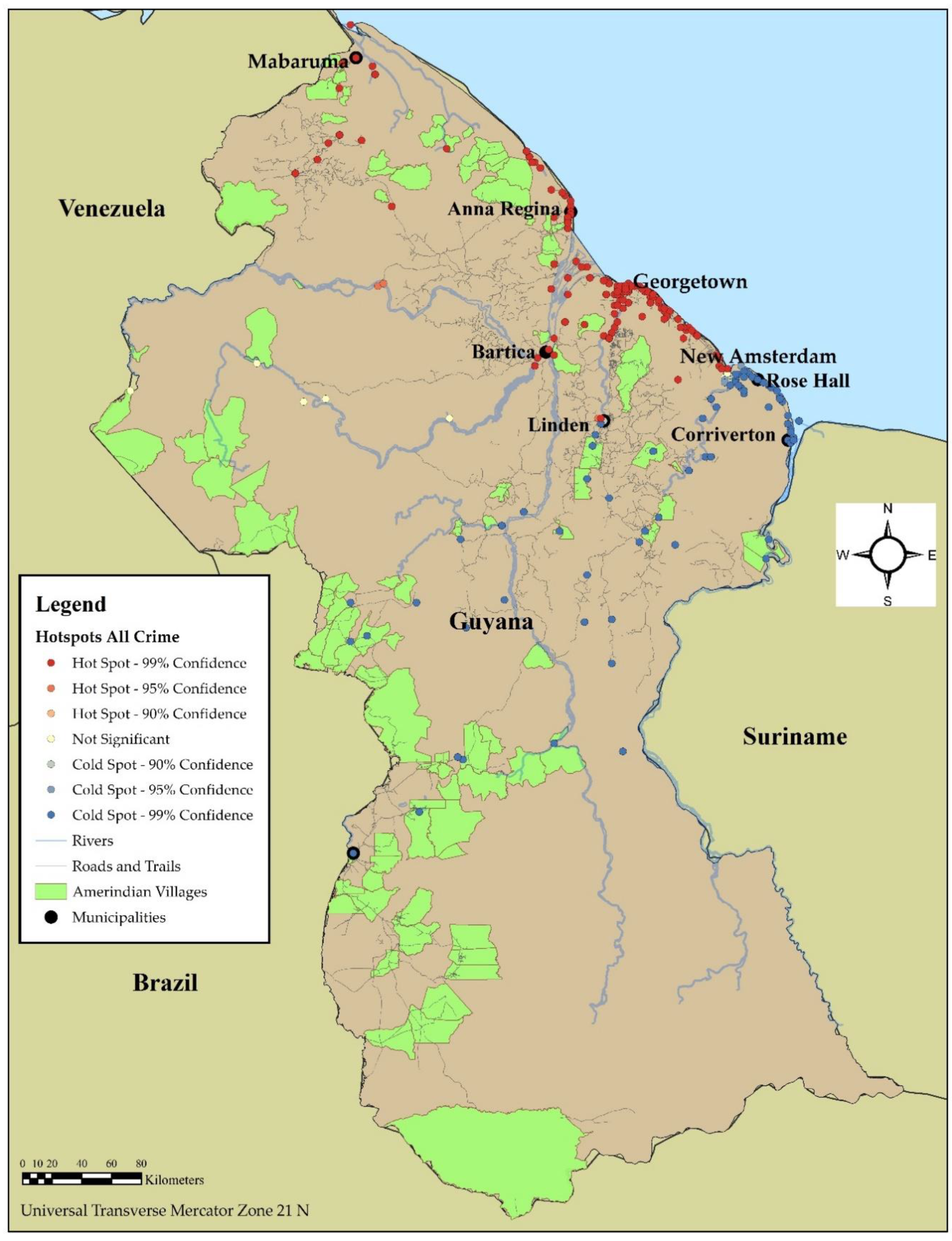

Despite the challenge of being able to accurately map the location of each crime, the data still suggested that crime in Guyana is a coastal feature, clustered around Georgetown and its environs, with significant hotspots along the coast (

Figure 2). Of all the crimes that were reported in the archives, around 10% were attributed directly to Georgetown, while an additional 25% occurred within the environs of Georgetown. Overall, as the data for the distribution of violent crime were analyzed for the twenty years, it was observed that the spatial distribution of crime, while centered on Georgetown and its environs, moved away from the coast, stretching northerly and southerly.

3.4. Distance of Crimes Relative to Indigenous Villages

The analysis of the distance between the mean centers of Amerindian villages to the mean center of the five violent crime types suggested that sexual violence (158.12 km) was closest to the villages’ mean center. Murders (161 km) and robbery (164 km) had the second and third closest average distances (

Table 2) to the Amerindian village mean centers.

3.5. Description of the Spatial Distribution of Violent Crime

The mean center of all violent crime pivoted around the Amerindian village of St. Cuthbert’s Mission (around 35.4 kilometers south-southwest of Georgetown), moving ever so slightly north and west of the village over the years. However, the mean center varied across the years covered in our analysis. As the period 1986–1991 had few crimes, these were aggregated for the analysis, and it was found that the mean center of crime was located south of River’s View Village and southwest of St. Cuthbert’s Mission during this time (see

Figure 3a). In the years 1993, 2001, 2007, 2008, and 2009, the mean center was located firmly within the northern portion of St. Cuthbert’s Mission land. The mean center’s position shifted towards the west of St. Cuthbert’s Mission in 1992, 1995, 1996, 1997, 2004, 2003, and 2010 (see

Figure 3b), with the distance from the village varying slightly.

In 1998, 1999, and 2002, the mean center was north of St. Cuthbert’s Mission, while for 1994 and 2005 the location was away from the village. In 1994, the mean center for violent crime was closest to the environs of Georgetown, while in 2005, the mean center was closest to the village of River’s View (see

Figure 3a).

Unlike the mean centers, the standard deviation ellipses showed that the distribution of crimes varied across the Guyanese coastal and terrestrial landscapes (see

Figure 3a,b,c). In 1994, for example, the ellipse was almost circular, trending slightly from north-northwest to south-southeast. The 1994 ellipse was located across Georgetown. The ellipse covering the period 1986–1991 was wider, relative to those for 1992, 1993, and 1995. Interestingly, it was the 1986–1991 ellipse that covered more area in the period 1986–1995, suggesting that violent crimes were more dispersed, certainly beyond coastal Guyana into the central part of the country. The ellipses for 1992, 1993, and 1995 had similar shapes, trending northeast to the southwest, but varied slightly in their lengths and widths. The ellipses for 1996–2000 (

Figure 3b) had different shapes and sizes but trended towards the northeast to southwest. The ellipses for 1998 and 1999 were more linear and, unlike the others, trended more north to south. Unlike the ellipse for 1994, which covered both coastal and inland Guyana, the 1996, 1997, and 2000 ellipses extended to inland Guyana but were more restricted along the coast. The ellipses for the years 2001–2005 showed a steady and gradual increase in coverage from central Guyana to northeastern Guyana (

Figure 3c). While the ellipse for 2001 was narrow and restricted along the road network, 2002 was more restricted lengthwise and was extended over more coastal areas. Like 2001 and 2003, 2004 trended more north to south, while 2004 and 2005 extended more toward the northwest and southwest. The ellipses for 2004 and 2005 showed a gradual increase in area covered into central Guyana. The ellipses for the years 2006 to 2010 (

Figure 3d) began to show a more definite pattern of crimes moving into the indigenous peoples influenced landscapes relative to the ellipses for 2004 and 2005. The 2006 ellipse extended northeast to southwest and covered more area than any other ellipse during the 2006–2010 period. The ellipses for 2007–2010, the period with the highest reports of violent crime, all trended almost north to south, including portions of the coastal landscape, but also showing a gradual movement into the areas beyond Georgetown. The 2007 and 2008 ellipses were narrower and shorter than the 2009 and 2010. However, for the 2007–2010 period, the 2010 ellipse covered the widest area (see

Figure 3d).

3.6. The Distribution of Murder

When the spatial distribution of murders and the weapons used to commit these acts were considered across the landscape, a wide variation in patterns was observed. In the analysis of the distribution from 1987–1991 (

Figure 4a), bladed weapons extended into central Guyana, covered a wider area of the country, and trended in an almost northeast to southwesterly direction. In contrast, firearms had a much narrower distribution and trended north to south. The mean center for both weapons was outside of St. Cuthbert’s Mission village, with firearms to the northeast of the village’s boundary and bladed weapons to the southwest. For the period 1996–2000 (

Figure 4b), the ellipses for bladed weapons and firearms trended in the same northeast to southwesterly direction, with bladed weapons wider than firearms. However, firearms extended further into central Guyana than bladed weapons. The mean center for bladed weapons was on St. Cuthbert’s Mission lands, while firearms were west of the village lands. The patterns for the two types of weapons had a noticeable contrast in the 2001–2005 period (

Figure 4c). While bladed weapons trended from the northeast to the southwest, firearms trended from the northwest to southeast but covered more areas along coastal Guyana and less inland. The mean center for the two weapons shifted further north during this period, with bladed weapons northwest of St. Cuthbert’s Mission and firearms east of the village of Santa Aratak. For the period 2006–2010 (

Figure 4d), bladed weapons covered more area than firearms. Bladed weapons extended further into central and coastal Guyana than firearms (

Figure 4d). For this period, the mean center for both weapons moved back south, with firearms almost on the lands of St. Cuthbert’s Mission’s northwestern boundary, while bladed weapons were further west of St. Cuthbert’s Mission (

Figure 4d). Overall, our analysis showed that even though coastal Guyana accounted for the majority of crimes, the center of gravity of these crimes shifted over the years to stretch into indigenous peoples-influenced landscapes.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper had two primary goals: (1) to examine the spatial distribution of violent crimes across Guyana and the relationship with indigenous lands; and (2) to examine the spatial distribution of murders committed using firearms and bladed weapons. Our analyses were based on the media reporting of crime, and we acknowledge that this dataset had challenges. Media houses and editors, for example, may be biased towards one type of crime over another, and therefore some types of crime may be given more coverage than others. We acknowledge too, that in our case the media reporting on crime was used as a proxy and we only obtained data from one media source. These points mean that our data do not give a comprehensive view of crime in Guyana. Yet, we believe our data provided a good sample from which we could draw some conclusions, for Guyana specifically and our understanding of the spatial distribution of crime more broadly. Through the process of examining the two goals we set out to address, several observations were made, and these are summarized below.

Firstly, the observation that the mean center of violent crime was located almost consistently on top of the Amerindian village of St. Cuthbert’s Mission raises concerns from a safety and law enforcement perspective. While the archives contained no data on violent crime occurring in St. Cuthbert’s, the distribution of violent crimes relative to the village requires additional investigation. Did our analysis, using centrographic tools, provide any insights into how the people of St. Cuthbert’s Mission view crime? In coastal Guyana, for example, people often take measures to prevent crime, including placing metal grills on doors and windows. Are similar measures being taken in St. Cuthbert’s Mission? Future work will seek to determine, from St. Cuthbert’s Mission and nearby villages, whether concerns exist for their safety and the measures that are being taken to prevent crime, relative to those seen in Georgetown and other coastal areas. When the first author visited St. Cuthbert’s Mission in spring 2019, there were no signals of violent crime in the village, but the non-violent crime of a businesswoman being sold counterfeit United States dollars was still being discussed among residents [

44]. St. Cuthbert’s Mission has clear and direct links to Georgetown, meaning it is more accessible than many other villages across the country. The implications of this accessibility will be investigated as part of a future research agenda. Undoubtedly though, the results of our analysis set up the conditions for understanding how crime is perceived within indigenous villages and whether there were observations of increased crimes within their villages that have not been reported in the newspaper we examined. As efforts are ongoing to map crime [

24], from environmental [

22] to homicides [

23] across Amazonia, our future work will continue this movement to understand how crime impacts indigenous peoples influenced landscapes.

Secondly, that fact firearms and bladed weapons had standard deviation ellipses that varied across the landscape (see

Figure 4), moving away from the coast, has implications for crime against the environment [

29,

30]. Firearms getting closer to indigenous villages can impact traditional hunting practices and threaten wildlife protection. Currently, indigenous peoples across Guyana have varying levels of dependence on wild game for food, with many still hunting as a part of their traditional livelihood practices [

45]. The movement of guns into indigenous peoples’ landscapes, carried by people who may have a different value for wildlife, can create competition over game species and wildlife protection. Based on the observation of crime concentration it appears as though the macro-level distribution of crime does now follow Weisburd’s [

30] law. Our analysis did not have the benefit of small streets and towns to extensively examine crime distribution within micro-places, yet we note that the movement of crime away from the coast could be triggered by a number of processes, including as people move into the forested for gold mining and other resource extraction activities. Gold miners, for example, tend to move into the forest in search of gold of the police and other social services [

46]. Cummings [

46] noted that because gold miners move ahead of the security services, many become vulnerable to banditry. To protect themselves, many gold miners take dogs into the forests, which then predisposes conflict with top predators, primarily jaguars (

Panthera onca) and pumas (

Puma concolor). While the standard deviation ellipse shows that guns are moving into the forests, the impacts on environmental crime will be a subject that will be addressed as a part of future research. Whether Weisburd’s laws of crime concentration are relevant to this landscape or perhaps other criminological theories will be the subject of future exploration. Understanding how the changes observed in crime patterns in the Guyanese context relate to observations in criminology, such as people’s lifestyles, routine activities, and opportunities for committing crime [

47,

48,

49], will be examined in the future. Such analyses will provide insight into where people may become vulnerable to criminal activity across space and time and develop predictive models to inform policing decision-making.

Thirdly, the newspaper archives allowed us to capture details on nearly 6000 crimes from only 37% of the days between 1986 and 2010. While capturing only 37% of days within the study period, the sample nevertheless provided us with a large volume of data from which we could gain insights into the spatial patterns of crime in Guyana. There was a contradiction in our observation of spatial patterns. While the use of mean centers and standard deviation ellipses showed that Weisburd’s laws may not be relevant to our dataset at the macro-place level, Hot Spot Analysis suggested a need for deeper analysis within micro-places. In fact, Hot Spot Analysis (

Figure 2) not only showed that crime was concentrated along the Guyanese coast, there were also hotspots in the gold mining areas of northern Guyana. The observation of crime along the coast is consistent with the findings of the work of Cummings et al. [

19], who used a much smaller sample (just over 600 violent crimes) to show that crime was concentrated around Georgetown. In this regard, the data derived from the media signal a need to look at both coastal (around Georgetown) and forested landscape micro-place crime patterns. These observations can potentially allow Guyanese law enforcement agencies to observe the areas that appear to host high levels of crime. Future work will seek to work with the law enforcement agencies to examine the crime patterns at both micro- and macro-places.

Finally, obtaining data from the archives was a time-consuming and laborious process, which could lead to data collection errors. Fortunately, only a small fraction of our sample could not be spatially referenced. Beyond the time required to collect the data from the archives, and the instances of not being able to determine the location where a crime was committed, other scholars seeking to collect data on crime for other developing country settings should be encouraged that our data were useful in allowing us to analyze the spatial nature of crime. Data from the media has long been identified as important for scientific research see [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55] and our analysis re-affirmed this point. However, we must also note that beyond the Stabroek News, there are three additional newspapers with online archives that can be used to crosscheck details on crime in Guyana. Future work will seek to obtain data from the archives of additional newspapers to compare how they report on the same crime event and, in turn, assess the newspapers’ reliability in reporting on crime.

In the final analysis, our work shows that guns and crime patterns have shifted towards indigenous peoples’ influenced landscapes. The porous nature of Guyana’s borders makes knowing the direction from which guns are arriving into the country a difficult task, but what is certain is that the center of gravity of such crime is changing, bringing violence closer to indigenous villages and, as Souza et al. [

23] observed, following the deforestation frontier. Furthermore, recent studies in North America [

47] have shown that gun policy in the United States impacted the movement of guns to, and subsequently the levels of crime in, Mexico. In the case of Guyana, guns used for crime on the coast can be later used to commit crimes in rural areas, and examining this question will be a part of future research. Developing policy to respond to the movement of gun-related crime is critical to protect indigenous peoples’ livelihood practices, including the wildlife on which they depend for food. Our work will continue to study how factors at both the local and global levels shape the spatial distribution of crime in Guyana.