An Analysis of the Differences in Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Review of Rural and Urban Areas in South Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

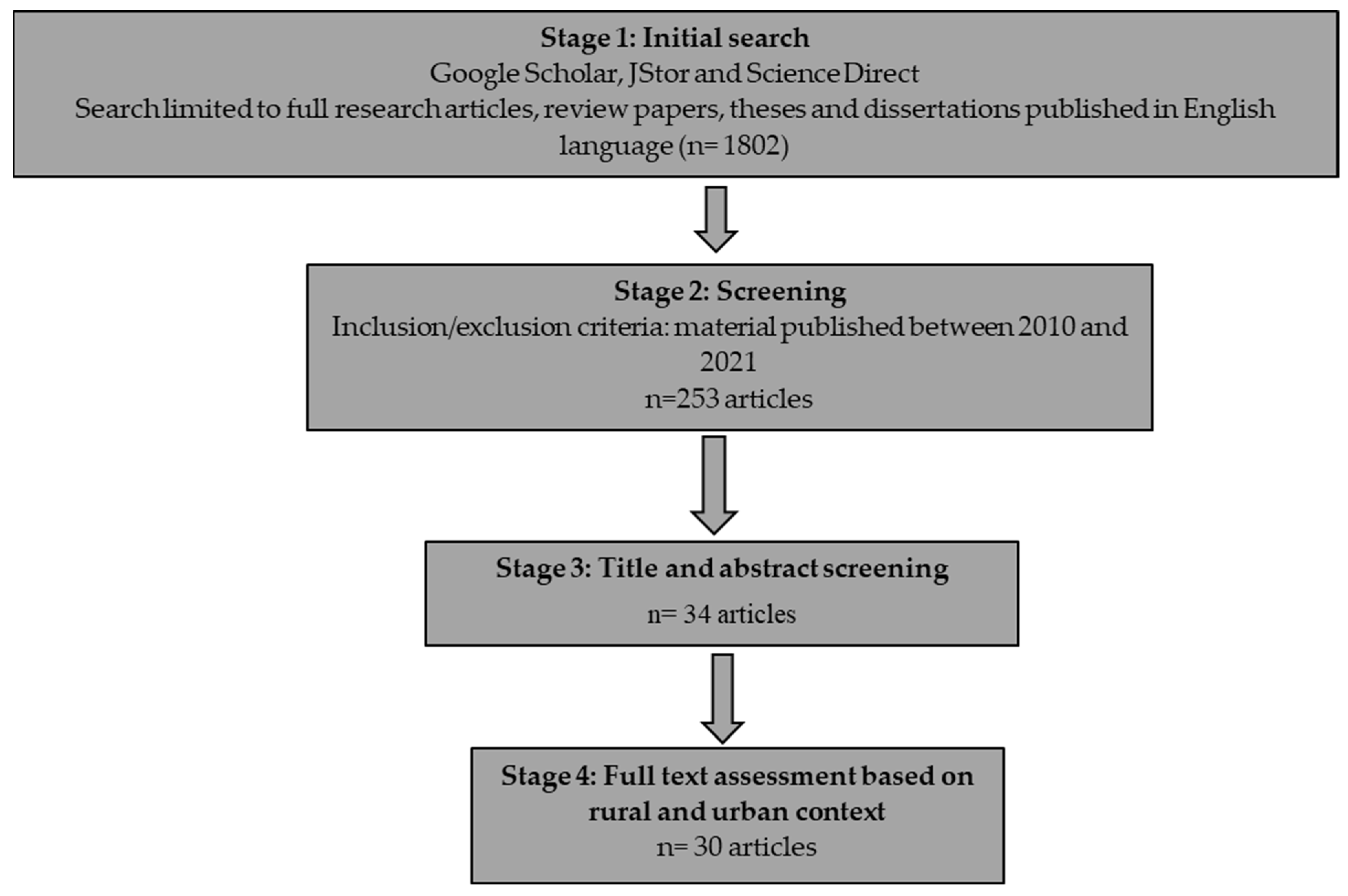

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy, Search Terms and Data Sources

2.2. Conceptual Framework

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Exposure of Rural and Urban Areas to Climate Change Stressors in South Africa

| Climate Stressors | Descriptors of Climate Stressors | Location and Source | Summary of the Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | Urban | Both Rural and Urban | |||

| Temperature variations | Fluctuating rate of temperature and long-term shifts in temperatures | Hitayezu et al. [29]; Ofoegbu et al. [30]; Goldin et al. [31]; Oosthuizen [32] | Jimoh et al. [33]; Orimoloye et al. [34]; Hlahla & Hill [35] | Gbetibouo et al. [36] Stadler [37] Jarganath et al. [38] | Temperature variations are common in both rural and urban areas. In rural areas, temperature variations are mainly experienced in arid and semi-arid regions. In urban areas, variations are experienced in sub-humid climates. |

| Rainfall variability | High inter-annual variability | Nyahunda et al. [39]; Jimoh et al. [33]; Hosu et al. [40]; | Williams et al. [41] | Gbetibouo et al. [36] Stadler [37] | Both rural and urban areas are exposed to rainfall variability. In rural areas farming households are more exposed. Public health, water, and sanitation services in urban areas are more at risk. |

| Extreme events | High incidence and frequency of extreme events such as droughts and floods | Ncube et al. [42]; Nembilwi et al. [43]; Munyai et al. [44]; Shisanya & Mafongoya [45] Ofoegbu et al. [30]; Udo [46]; Oosthuizen [32]; Goldin et al. [31]; Shackleton et al. [47]; | Orimoloye et al. [34]; Membele et al. [48]; Williams et al. [41]; Hlahla & Hill [35] | Gbetibouo et al. [36] Stadler [37] | Rural and urban areas in South Africa are exposed to droughts and floods. Differences are noted with exposure to drought, mainly in rural areas, while urban areas are more exposed to floods. Hailstorms are more common in urban areas. |

| Seasonal variations | Increased variations in temperature and rainfall between seasons | Hitayezu et al. [29] Goldin et al. [31] | Hlahla & Hill [35] | Long summers and short winters characterised by cold spells and frost occurrences are common in both rural and urban areas. | |

3.2. Sensitivity to Climate Change in Rural and Urban Areas in South Africa

| Rural | Urban | Both Rural and Urban | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Major Results | Source | Major Results | Source | Major Results |

| Ncube et al. [42] | Households in Alice, Eastern Cape are more sensitive than in households in Lambani, Limpopo. | Jimoh et al. [33] | Most households across selected towns in Mopani District were not sensitive to climate change stressors. | Gbetibouo et al. [36] | The most sensitive provinces are Limpopo, Kwazulu-Natal, and Eastern Cape. |

| Hitayezu et al. [29] | Farming systems with small-scale farming, low irrigation rates, and that are prone to land degradation are highly sensitive. Diversified crop systems have high resilience. | Williams et al. [41] | The sensitivity of informal settlements to flooding is influenced by levels of education, access to public services, provision of basic infrastructure, and health standards. | Stadler [37] | Formal residential areas (suburbs) with high household ownership levels, green open spaces, vegetation, and commercial or mixed land uses are less sensitive. |

| Ofoegbu et al. [30] | Forest-based communities have uneven sensitivity due to uneven exposure to various types and magnitudes of stressors. | Orimoloye et al. [34] | Human health is extremely sensitive to extreme weather. | Stadler et al. [37] | People living in rural areas of Gatyana are more sensitive to HIV/AIDS and climate change than people in urban areas owing to the diseases’ associations with marginalised communities. |

| Goldin et al. [31] | Women and girls are more sensitive than males. | Hlahla and Hill [35] | Socio-economically marginalised urban communities are highly sensitive to seasonal variations, drought, heat waves, cold spells, hailstorms, and floods. | Chersich et al. [49] | The most sensitive populations in South Africa are women, fishing communities, subsistence farmers, and those living in informal settlements. |

| Shackleton et al. [47] | Households’ sensitivity is a function of livelihood activities, poverty levels, and asset holdings. | Wedepohl [50] | Sensitivity to climate change stressors differs between informal and formal settlements. | Chikulo [51] | Differences in sensitivity are noted between women in electrified urban homes and rural women with non-electrified homes. |

| Udo [46] | Women’s sensitivity to floods is increased by poverty, inequality, marginalisation, lack of access to loans and insurance, poor quality of houses and other infrastructure, and lack of knowledge and education. | - | - | - | - |

| Oosthuizen [32] | Farming systems are sensitive to climate-induced financial vulnerability. | - | - | - | - |

| Shackleton and Cobban [52] | Rural women are highly sensitive to climate change due to reliance on ecosystem services, low income, labour constraints, and poor health. | - | - | - | - |

| Abayomi [53] | People living with HIV/AIDS are more sensitive to climate change stressors and are at a health disadvantage in a changing climate. | - | - | - | - |

| Mugambiwa and Tirivangasi [54] | Poor rural communities in South Africa are immensely susceptible to climate change owing to a lack of livelihood assets leading to increased hunger and malnutrition. | - | - | - | - |

| Munyai et al. [44] | The nature of soil and type of dwelling are the most important factors influencing sensitivity to climate change in rural areas. | - | - | - | - |

| Own critical analysis | Rural: Households, farming systems, ecological zones, communities, and villages in rural areas are sensitive to climate change. The type and nature of farming systems significantly bear on sensitivity levels. “Forest-based” rural communities are differentially sensitive due to different forest types. | Urban: Sensitivity to climate change varies between formal and informal settlements in urban areas. Informal settlements are more sensitive to climate change. “Urban poor” communities are highly sensitive because most are socio-economically marginalised. | Both: Female-headed households are more sensitive to climate change than male-headed households. | ||

| A spatial perspective | Households in rural areas are more susceptible to climate change than urban areas. Sensitivity at the household level varies between rural and urban areas. Rural communities are unevenly sensitive at the community level, while urban communities are highly sensitive. | ||||

3.3. Adaptive Capacity of Rural and Urban Areas in South Africa

| Rural | Urban | Both | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Major Results | Source | Major Results | Source | Major Results |

| Ncube et al. [42] | The adaptive capacity of households is influenced by human, physical, financial, natural, and social capital. | Jimoh et al. [33] | A significant proportion of sampled households (76.2%) could adapt to climate change impacts. | Gbetibouo et al. [36] | The Western Cape province has the highest adaptive capacity due to its well-developed infrastructure, high levels of literacy and income, low levels of unemployment, and HIV prevalence. |

| Hitayezu et al. [29] | Adaptive capacity is limited by inadequate access to infrastructure, rural exodus, skills shortages, poor health status, and lack of cooperation among farmers. | Williams et al. [41] | Governance shapes education standards, delivery of public services, provision of basic infrastructure, and the standard of health and economic facilities, which influence adaptive capacity in informal settlements. | - | - |

| Ofoegbu et al. [30] | The adoption of adaptation measures in rural communities is appreciated; however, capacity is often insufficient to maintain resilience and sustainability. | Hlahla and Hill [35] | The majority do not have the means to respond to climate change impacts due to a lack of education and the belief that nothing can be done to deal with climate change. | - | - |

| Goldin et al. [31] | Political freedom, economic facilities, social opportunities, and protective security are necessary for women to enhance their adaptive capacity. | Membele et al. [48] | People in informal settlements have differentiated adaptive capacities. Indigenous knowledge strengthens adaptive capacities in informal settlements. | - | - |

| Shackleton et al. [47] | Gender-based violence is cited as one factor diminishing women’s adaptive capacity in rural areas. | Wedepohl [50] | The interrelatedness of the available types of capital impacts the resilience and adaptive capacity of informal and formal settlements. | - | - |

| Udo [46] | Although women demonstrated “agency” in adapting to floods, their adaptive capacity is often limited by poverty, increased levels of abuse, and lack of political connections. | Roberts and O’Donoghue [61] | The adaptive capacity of the city of Durban is low due to several factors, including high rates of poverty and unemployment, and a lack of skilled human resources to carry out adaptation planning and implementation, among other challenges. | - | - |

| Oosthuizen [32] | Biophysical factors are important in improving the adaptive capacity of farming systems. | Ziervogel et al. [62] | Major factors reducing adaptive capacity at the Municipal level are inadequate communication between scientists, policymakers, and practitioners, a lack of coordination between different scales of operation, and a lack of human capacity to implement policy. | - | - |

| Quinn et al. [63] | Social, economic, and political conditions shape adaptive capacity; hence, adaptation processes should not be viewed in isolation, but a holistic approach should be adopted to account for all those factors. | - | - | - | - |

| Nyahunda et al. [39] | Gender inequalities manifesting through unequal land and property rights, discrimination in the decision-making process, and unequal sharing of burdens undermine women’s adaptive capacity. | - | - | - | - |

| Own critical analysis | Rural: Adaptive capacity is influenced by the five main types of capital: human, physical, financial, natural, and social capital in both rural and urban areas. Rural communities make use of adaptive measures, but their capacity is often insufficient to match the ever-increasing climate changes. | Urban: Urban areas of South Africa have shown differentiated adaptive capacity. | Both: Highly developed regions have a higher adaptive capacity than less developed regions. | ||

| A spatial perspective | Although climate change is not gender-neutral, women are assumed to have less adaptive capacity. Poverty is the greatest limitation in adapting to climate change for both females and males. Women do not always have a say in adaptation decisions. This situation makes them more dependent on men’s decisions and more vulnerable to climate change impacts. | ||||

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Santos-Lacueva, R.; Clavé, S.A.; Saladié, Ò. The vulnerability of coastal tourism destinations to climate change: The usefulness of policy analysis. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žurovec, O.; Čadro, S.; Sitaula, B. Quantitative assessment of vulnerability to climate change in rural municipalities of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.M.; Adger, W.N. Theory and practice in assessing vulnerability to climate change and facilitating adaptation. Clim. Chang. 2000, 47, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, N. Vulnerability, Risk and Adaptation: A Conceptual Framework; Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research: Norwich, UK, 2003; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, K.; Sygna, L.; Haugen, J.E.; Dokken, D.J. Vulnerable or Resilient? A Multi-Scale Assessment of Climate Impacts and Vulnerability in Norway. Clim. Chang. 2004, 64, 193–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.J.; Canziani, O.F.; Leary, N.A.; Dokken, D.J.; White, K.S. Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability: Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Füssel, H.-M.; Klein, R.J. Climate change vulnerability assessments: An evolution of conceptual thinking. Clim. Chang. 2006, 75, 301–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elum, Z.A.; Modise, D.M.; Marr, A. Farmer’s perception of climate change and responsive strategies in three selected provinces of South Africa. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017, 16, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, C.B.; Barros, V.; Stocker, T.F.; Dahe, Q. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, C.K.; Bennett, N.J.; Ban, N.C.; Allison, E.H.; Armitage, D.; Blythe, J.L.; Burt, J.M.; Cheung, W.; Finkbeiner, E.M.; Kaplan-Hallam, M. Adaptive capacity: From assessment to action in coastal social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thywissen, K. Components of Risk: A Comparative Glossary; UNU-EHS: Shibuya, Tokyo, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Torresan, S.; Critto, A.; Dalla Valle, M.; Harvey, N.; Marcomini, A. Assessing coastal vulnerability to climate change: Comparing segmentation at global and regional scales. Sustain. Sci. 2008, 3, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Government of the Republic of South Africa. National Climate Change Response White Paper. 2011. Available online: https://cer.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/White-Paper-on-Climate-Change-Response-Oct-2011.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Atkinson, D. Rural-urban linkages: South Africa case study. In Territorial Cohesion for Development Program; Rimisp: Santiago, Chile, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Vision. Defining Urban Contexts. 2017. Available online: https://www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/Defining%20urban%20contexts%2012.11.17.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Collinson, M.; Tollman, S.M.; Kahn, K.; Clark, S.; Garenne, M. Highly prevalent circular migration: Households, mobility and economic status in rural South Africa. In Proceedings of the Conference on African Migration in Comparative Perspective, Johannesburg, South Africa, 4–7 June 2003; pp. 194–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kok, P.; Collinson, M. Migration and Urbanisation in South Africa; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Long, D.; Ziervogel, G. Vulnerability and adaptation to climate change in urban South Africa. In Urban Geography in South Africa; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, M.; Masubelele, M.; Cupido, C.; Swarts, M.; Foster, J.; De Wet, G.; Links, A.; Van Orsdol, K.; Lynes, L. Climate vulnerability and risks to an indigenous community in the arid zone of South Africa. J. Arid Environ. 2022, 199, 104718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, A.L.; Carden, K.; Teta, C.; Wågsæther, K. Water, sanitation, and hygiene vulnerability among rural areas and small towns in south Africa: Exploring the role of climate change, marginalization, and inequality. Water 2021, 13, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, M.L.; Canziani, O.; Palutikof, J.; Van der Linden, P.; Hanson, C. Climate Change 2007-Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L. Vulnerability to environmental hazards. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1996, 20, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, J.B. Reviewing the Argument on Floods in Urban Areas: A Look at The Causes. Theor. Empir. Res. Urban Manag. 2020, 15, 24–41. [Google Scholar]

- Winsemius, H.C.; Jongman, B.; Veldkamp, T.I.; Hallegatte, S.; Bangalore, M.; Ward, P.J. Disaster risk, climate change, and poverty: Assessing the global exposure of poor people to floods and droughts. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2018, 23, 328–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, L.T.; Jou, S.C.; Lin, J.-H. Gender inequality and adaptive capacity: The role of social capital on the impacts of climate change in Vietnam. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.; Thatcher, M.; Salazar, A.; Watson, J.E.; McAlpine, C.A. The impact of climate change and urban growth on urban climate and heat stress in a subtropical city. Int. J. Climatol. 2019, 39, 3013–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abay, K.A.; Koru, B.; Chamberlin, J.; Berhane, G. Does rainfall variability explain low uptake of agricultural credit? Evidence from Ethiopia. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2021, 49, 182–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitayezu, P.; Zegeye, E.W.; Ortmann, G.F. Some aspects of agricultural vulnerability to climate change in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands, South Africa: A systematic review. J. Hum. Ecol. 2014, 48, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofoegbu, C.; Chirwa, P.; Francis, J.; Babalola, F. Assessing vulnerability of rural communities to climate change: A review of implications for forest-based livelihoods in South Africa. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 11, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, J.; Botha, C.; Koatla, T.; Anderson, K.; Owen, G.; Lebese, A. Towards a gender sensitive vulnerability assessment for climate change: Lambani, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 12, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosthuizen, H.J. Modelling the Financial Vulnerability of Farming Systems to Climate Change in Selected Case Study Areas in South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jimoh, M.Y.; Bikam, P.; Chikoore, H. The Influence of Socioeconomic Factors on Households’ Vulnerability to Climate Change in Semiarid Towns of Mopani, South Africa. Climate 2021, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orimoloye, I.R.; Mazinyo, S.P.; Kalumba, A.M.; Ekundayo, O.Y.; Nel, W. Implications of climate variability and change on urban and human health: A review. Cities 2019, 91, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlahla, S.; Hill, T.R. Responses to climate variability in urban poor communities in Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sage Open 2018, 8, 2158244018800914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbetibouo, G.A.; Ringler, C.; Hassan, R. Vulnerability of the South African Farming Sector to Climate Change and Variability: An Indicator Approach; Natural Resources Forum; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Stadler, L.T. Assessing Household Assets to Understand Vulnerability to HIV/Aids and Climate Change in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jagarnath, M.; Thambiran, T.; Gebreslasie, M. Heat stress risk and vulnerability under climate change in Durban metropolitan, South Africa—identifying urban planning priorities for adaptation. Clim. Chang. 2020, 163, 807–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyahunda, L.; Makhubele, J.C.; Mabvurira, V.; Matlakala, F.K. Vulnerabilities and inequalities experienced by women in the climate change discourse in South Africa’s rural communities: Implications for social work. Br. J. Soc. Work 2021, 51, 2536–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosu, S.Y.; Cishe, E.; Luswazi, P. Vulnerability to climate change in the Eastern Cape province of south Africa: What does the future holds for smallholder crop farmers? Agrekon 2016, 55, 133–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.S.; Manez Costa, M.; Sutherland, C.; Celliers, L.; Scheffran, J. Vulnerability of informal settlements in the context of rapid urbanization and climate change. Environ. Urban. 2019, 31, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, M.; Madubula, N.; Ngwenya, H.; Mthunzi, T.; Madzivhandila, T.; Zinyengere, N.; Olivier, C.; Zhou, L.; Francis, J. Climate change, household vulnerability and smart agriculture: The case of two South African provinces. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2016, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nembilwi, N.; Chikoore, H.; Kori, E.; Munyai, R.B.; Manyanya, T.C. The Occurrence of Drought in Mopani District Municipality, South Africa: Impacts, Vulnerability and Adaptation. Climate 2021, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyai, R.B.; Nethengwe, N.S.; Musyoki, A. An assessment of flood vulnerability and adaptation: A case study of Hamutsha-Muungamunwe village, Makhado municipality. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2019, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shisanya, S.; Mafongoya, P. Assessing rural farmers perceptions and vulnerability to climate change in uMzinyathi District of Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 12, 815–828. [Google Scholar]

- Udo, F.J. Gender and climate change adaptation in South Africa: A case study of vulnerability and adaptation experiences of local black African women to flood impacts within the eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality. Ph.D. Thesis, University of KwaZulu Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton, S.; Cobban, L.; Cundill, G. A gendered perspective of vulnerability to multiple stressors, including climate change, in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa. Agenda 2014, 28, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Membele, G.M.; Naidu, M.; Mutanga, O. Integrating Indigenous Knowledge and Geographical Information System in mapping flood vulnerability in informal settlements in a South African context: A critical review. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chersich, M.F.; Wright, C.Y.; Venter, F.; Rees, H.; Scorgie, F.; Erasmus, B. Impacts of climate change on health and wellbeing in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wedepohl, P.C. Differentiating Vulnerability to Climate Change; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chikulo, B.C. Gender, climate change and energy in South Africa: A review. Gend. Behav. 2014, 12, 5957–5970. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton, S.; Cobban, L. Gender and vulnerability to multiple stressors, including climate change, in rural South Africa. In Gender and Forests; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 156–179. [Google Scholar]

- Abayomi, A.; Cowan, M. The HIV/AIDS epidemic in South Africa: Convergence with tuberculosis, socioecological vulnerability, and climate change patterns. SAMJ S. Afr. Med. J. 2014, 104, 583–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugambiwa, S.S.; Tirivangasi, H.M. Climate change: A threat towards achieving ‘Sustainable Development Goal number two’(end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture) in South Africa. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildrexler, D.; Yang, Z.; Cohen, W.B.; Bell, D.M. A forest vulnerability index based on drought and high temperatures. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 173, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nellemann, C.; Verma, R.; Hislop, L. Women at the Frontline of Climate Change: Gender Risks and Hopes; A Rapid Response Assessment, United Nations Environment Programme, GRID-Arendal; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Babugura, A.; Mtshali, N.; Mtshali, M. Gender and Climate Change: South Africa Case Study; Heinrich Böll Stiftung Southern Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ribot, J.C. Vulnerability does not just come from the sky: Framing grounded pro-poor cross-scale climate policy. In Social Dimensions of Climate Change: Equity and Vulnerability in a Warming World; New Frontiers of Social Policy; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wabiri, N.; Taffa, N. Socio-economic inequality and HIV in South Africa. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heltberg, R.A.; Bonch-Osmolovkiy, M. Mapping Vulnerability to Climate Change; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, D.; O’Donoghue, S. Urban environmental challenges and climate change action in Durban, South Africa. Environ. Urban. 2013, 25, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziervogel, G.; Shale, M.; Du, M. Climate change adaptation in a developing country context: The case of urban water supply in Cape Town. Clim. Dev. 2010, 2, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, C.H.; Ziervogel, G.; Taylor, A.; Takama, T.; Thomalla, F. Coping with multiple stresses in rural South Africa. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Butler, C.; Walker-Springett, K. Moral reasoning in adaptation to climate change. Environ. Polit. 2017, 26, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Razak, M.; Kruse, S. The adaptive capacity of smallholder farmers to climate change in the Northern Region of Ghana. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017, 17, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Wandel, J. Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, N.; Hugé, J.; Boon, E.; Gain, A.K. Climate change impacts in agricultural communities in rural areas of coastal Bangladesh: A tale of many stories. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8437–8460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtezion, S. Overview of linkages between gender and climate change. In Policy Brief; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, J.J.; Canziani, O.F.; Leary, N.A.; Dokken, D.J.; White, K.S. Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Serumaga-Zake, P.; Naudé, W. The determinants of rural and urban household poverty in the North West province of South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2002, 19, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, P.; Mahanta, B. Women empowerment in India. Bull. Polit. Econ. 2012, 5, 155–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of literature source | Full research articles | 22 |

| Review papers | 4 | |

| Theses/dissertations | 4 | |

| Category | Rural | 16 |

| Urban | 8 | |

| Both | 6 | |

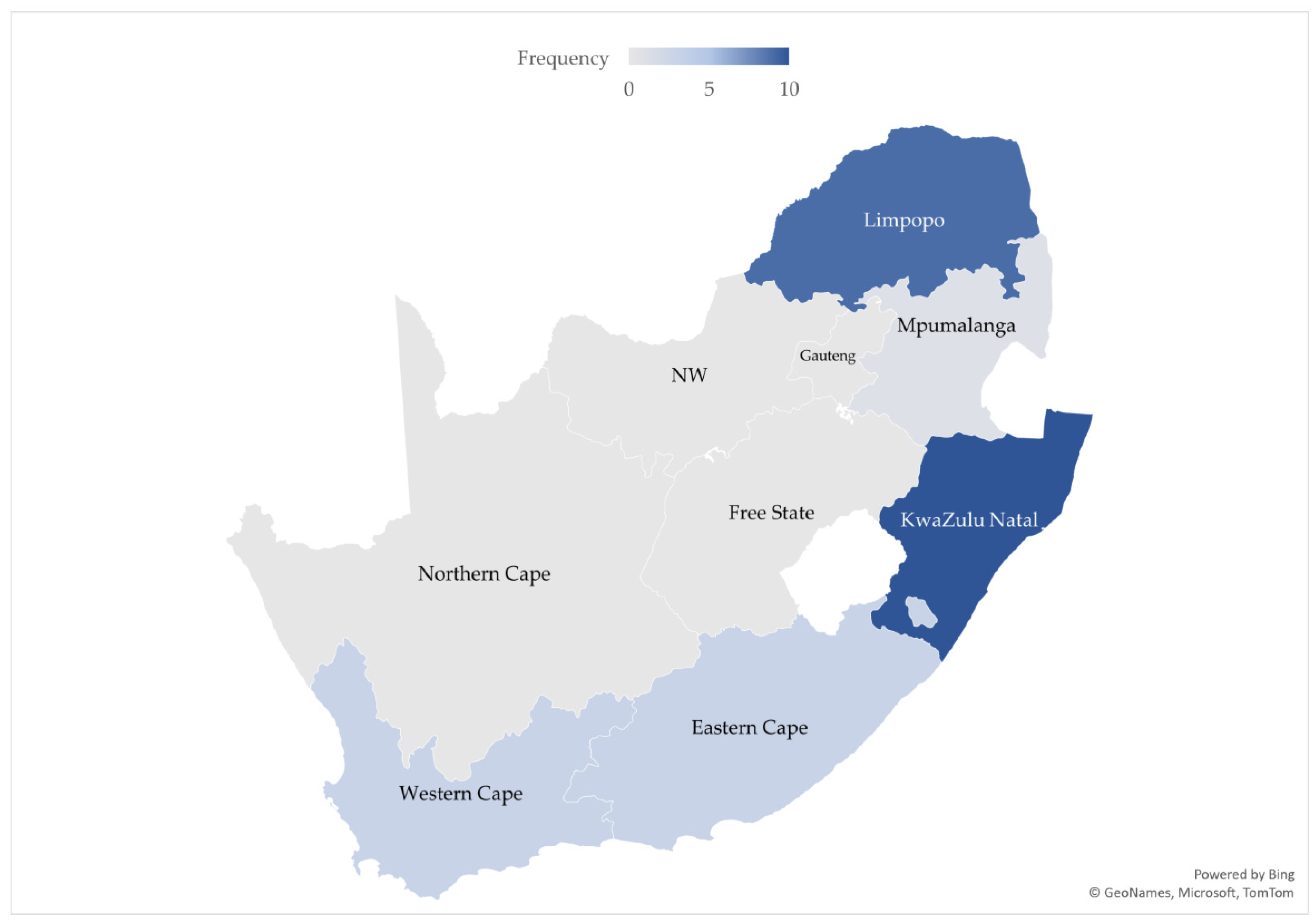

| Province | Limpopo, | 9 |

| Mpumalanga, | 1 | |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 10 | |

| Eastern Cape | 3 | |

| Western Cape | 3 | |

| Countrywide | 7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, L.; Kori, D.S.; Sibanda, M.; Nhundu, K. An Analysis of the Differences in Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Review of Rural and Urban Areas in South Africa. Climate 2022, 10, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli10080118

Zhou L, Kori DS, Sibanda M, Nhundu K. An Analysis of the Differences in Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Review of Rural and Urban Areas in South Africa. Climate. 2022; 10(8):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli10080118

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Leocadia, Dumisani Shoko Kori, Melusi Sibanda, and Kenneth Nhundu. 2022. "An Analysis of the Differences in Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Review of Rural and Urban Areas in South Africa" Climate 10, no. 8: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli10080118

APA StyleZhou, L., Kori, D. S., Sibanda, M., & Nhundu, K. (2022). An Analysis of the Differences in Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Review of Rural and Urban Areas in South Africa. Climate, 10(8), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli10080118