1. Introduction

Climate change is an undeniable reality, causing significant impacts across the globe. Human activities have exacerbated the situation, resulting in observed changes in weather events and extreme climate phenomena. The global sea level has risen by an average of 3.7 mm per year over the past decade, which is twice the rate of sea level rise in the 20th century [

1]. The concentration of carbon dioxide in the earth’s atmosphere has risen to its highest level in at least 3 million years, as a result of human activities, such as burning fossil fuels and deforestation [

2].

Climate change is leading to changes in the timing and distribution of rainfall, resulting in more frequent and severe droughts in some areas and more intense rainfall in others. For example, Asia and Africa face an increased likelihood of droughts, while monsoon regions in Southeast Asia are expected to experience more floods and heavy rains [

3]. These catastrophic weather events have dire consequences for the livelihoods of millions, particularly for those living in remote mountainous regions who rely on agriculture. Research on the impact of climate change and variability on community livelihoods has increased in recent years, with a focus on assessing the vulnerability of agricultural communities and risk-prone areas [

4,

5,

6]. However, there remains a significant lack of integration of status, ethnicity, and gender aspects in the resilience literature, although recent efforts have been made to address this gap [

7,

8]. There is also a need to expand research on household livelihood resilience, an area that has received limited attention to date. With the impact of climate change becoming more apparent, it is crucial to study its effects on community livelihoods at multiple levels and to identify ways to improve resilience.

Resilience is a concept that has gained widespread use among international humanitarian agencies, policymakers, and development practitioners as a framework for sustainable development [

9]. It is often employed in response to the perception that various shocks, including those related to climate change, present significant challenges to development efforts [

10,

11]. While gender issues and ethnic minority groups have been examined in several climate studies, ethnicity has often overshadowed gender analysis [

4,

12,

13,

14]. Furthermore, most studies have focused solely on women rather than exploring gender dynamics more broadly, even though gender is a complex concept that intersects with other factors, such as socioeconomic status, ethnicity, geographic location, and disability, among others [

15]. This concept of intersectionality is crucial to understanding resilience, as climate shocks become increasingly unpredictable and communities face new challenges.

Recent studies suggest that the socioeconomic disparities between social groups are likely to widen due to the impacts of climate change [

16,

17]. As a result, it is essential to understand the factors that contribute to these inequalities. Gender, in particular, should not be viewed simply as a binary variable, but as a dynamic social entity that intersects with a range of factors, including rights, roles, identities, and responsibilities [

18]. Without a comprehensive cross-sectional analysis of gender and ethnicity in climate resilience, disproportionate impacts will persist, hindering progress towards achieving sustainable development goals related to gender equality and community development [

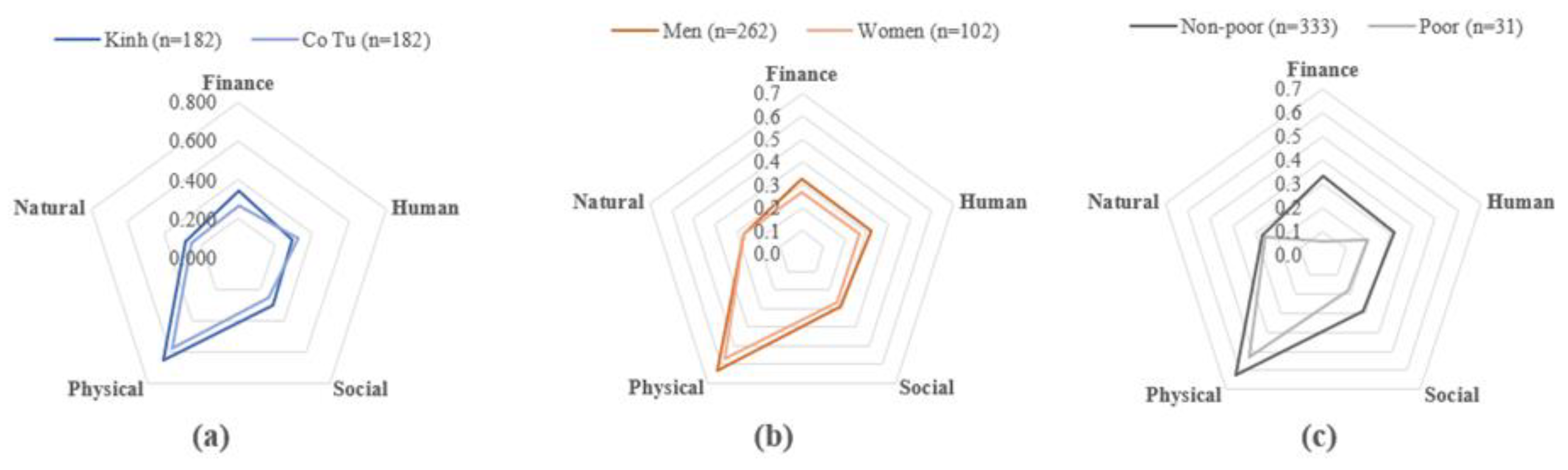

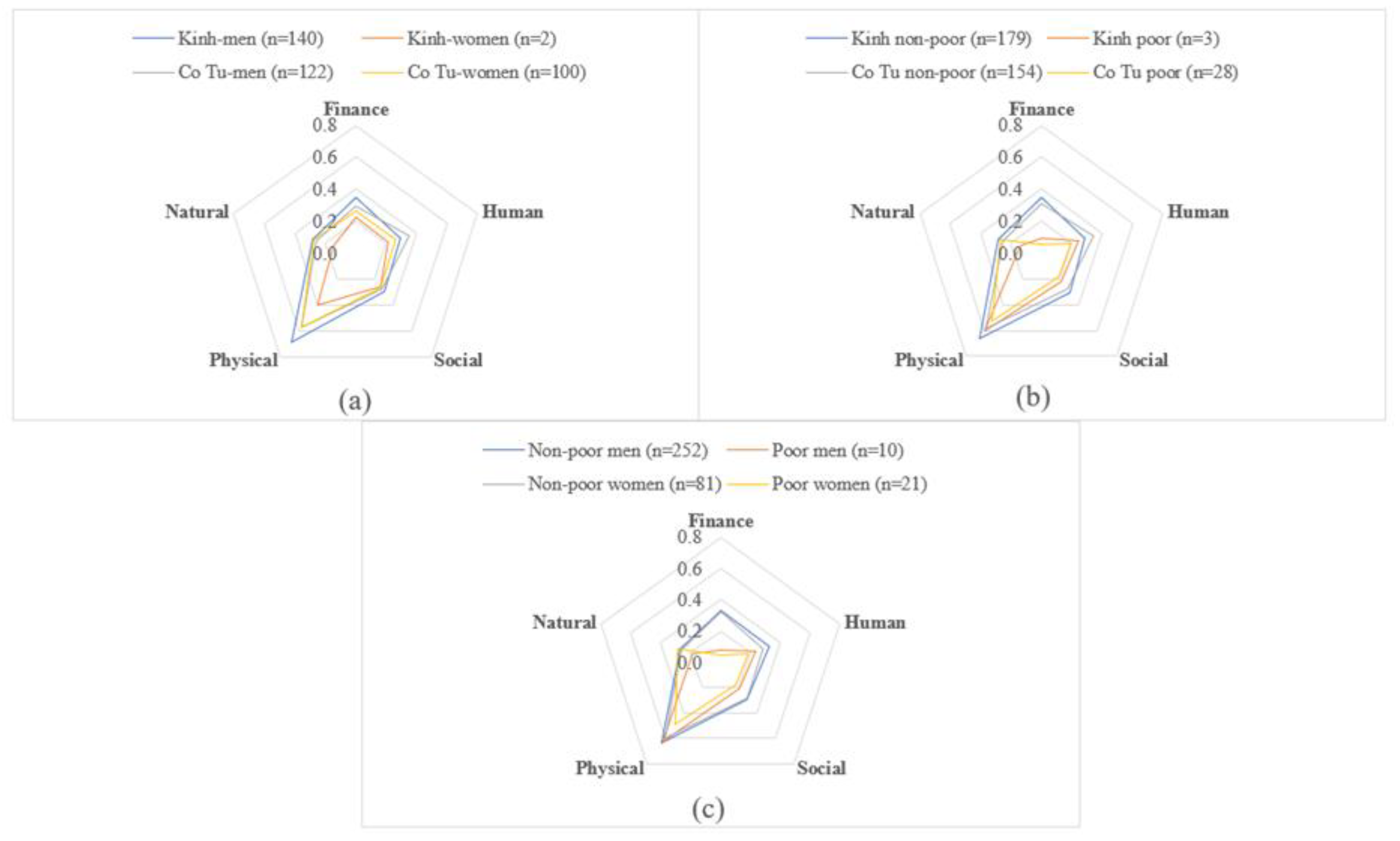

17]. The present investigation aims to scrutinize the variations in the resilience of livelihoods, based on distinct categories, such as economic status (poor and well-off households), sex (men and women), and ethnicity (Kinh majority and Co Tu minority groups), within two highland communities located in the Nam Dong District of the Thua Thien Hue Province in Central Vietnam. The study aims to contribute to the evolving understanding of climate resilience by exploring the intersectionality of these factors. By doing so, the study provides two noteworthy contributions: theoretically, it expands the existing literature on climate resilience with regard to gender and ethnicity, and practically, it proposes policy recommendations for development practitioners, planners, and humanitarian agencies to implement more equitable and sustainable interventions for disaster reduction and resilience-building programs.

5. Discussion and Implications

Our study yielded four significant findings related to the livelihood resilience of upland households in Vietnam. These findings have important implications for policies and programs aimed at enhancing the resilience of vulnerable communities.

First, our results indicate that men generally exhibit higher levels of livelihood resilience than women across all social groups, highlighting the need to address gender inequalities in disaster risk reduction and resilience-building efforts. This further supports previous findings [

8,

12]. To this end, policies and programs should strive to promote gender equality in access to resources, decision making, and leadership roles. We also found that Co Tu women have greater human capital than Kinh women, attributed to their knowledge of the impact of climate change on their lives, particularly in agriculture. Consequently, they actively engage in disaster prevention training courses and drills, which effectively build resilience and rehabilitate communities’ livelihoods. Thus, we recommend expanding these training initiatives to include individuals from other sectors, not just agriculture. However, our study also reveals that the educational level of the Co Tu ethnic group, particularly women, is very low. Therefore, to increase the effectiveness of such training courses, it is essential to concurrently address the issue of education improvement [

13,

14]. Urgent tasks include opening free literacy classes for the elderly and encouraging ethnic minority students to attend school [

7]. We also highlight the need to integrate social and ethical issues, such as local limitations and perceptions, and capabilities of the locality when designing any community-based resilience-building program.

Second, our study reveals that households belonging to better-off economic strata exhibit higher resilience scores for both Kinh and Co Tu households. This finding underscores the significance of addressing economic disparities to enhance the resilience of vulnerable communities. To this end, policies and programs should prioritize poverty alleviation and promote inclusive economic growth. Nonetheless, reducing poverty remains a formidable challenge that requires attention. In this article, we propose three main strategies to reduce poverty for upland farmers. First, increasing access to productive resources, such as land, credit, and technology, is essential. Previous research has demonstrated that providing small farmers with access to these resources can significantly improve their incomes and reduce poverty [

6,

8]. Second, enhancing productivity and competitiveness through better production practices, value chain development, and market linkages can also increase incomes and reduce poverty [

36,

37]. This necessitates investment in infrastructure, research and development, and extension services. Furthermore, encouraging off-farm income and using potential resources in locals, such as rural community tourism or craft villages such as local silk products, can also be advantageous [

7,

38,

39,

40]. Lastly, strengthening governance and institutions is vital to improving access to resources, services, and markets [

5]. Weak governance and institutions in upland areas can restrict access, thus hindering poverty reduction efforts. Strengthening governance and institutions through decentralization, participatory planning, and community-based natural resource management can enhance access and reduce poverty. It is also crucial to recognize the diversity of upland communities in terms of ethnicity, culture, and livelihoods. Policies and programs should be designed to address the specific needs and constraints of different upland communities to effectively reduce poverty.

Third, our study has revealed that poor Co Tu households and poor households led by women have the lowest climate resilience ability. This finding underscores the importance of tailoring disaster reduction and resilience-building policies to these groups [

10,

14,

35,

41]. Specifically, policies and programs should target these groups with tailored interventions that address their specific vulnerabilities and build their resilience. These results highlight the importance of financial support and human capital enhancement policies for poor households. Policies aimed at improving financial capital can help poor households better withstand and recover from climate shocks. Similarly, interventions to enhance human capital, such as education and training, can help build the capacity of poor households to adapt to changing climatic conditions. However, it is important to note that while economic status is a key factor in determining resilience, other factors, such as access to information, social networks, and cultural practices, also play important roles. Therefore, policies and interventions should be designed with a holistic and intersectional approach that considers the multidimensional nature of vulnerability and resilience. Additionally, several recent studies have suggested that providing interest-free or low-interest credit programs for women’s union members or those living in poverty could enhance their ability to access capital, thereby increasing their capacity to adapt to disaster risks and ultimately improving the resilience of households [

8,

42,

43].

Finally, our study indicates that financial, social, and human livelihood capitals are critical in enhancing the resilience of upland households in Vietnam. These findings have important implications for policymakers and practitioners working to enhance the resilience of vulnerable communities. Specifically, interventions should focus on improving access to financial, social, and human capital for the most vulnerable households, with an emphasis on ethnic minority communities. To operationalize this, we propose the following recommendations: First, microfinance programs can provide small loans to vulnerable households to establish or expand small businesses, improving their economic resilience [

8]. Second, investing in education and skills development can equip vulnerable households, especially ethnic minorities, with the necessary skills and knowledge to access better job opportunities, hence improving their financial resilience. Third, social safety net programs, such as conditional cash transfers, can provide vulnerable households with a safety net during crises, such as natural disasters or economic shocks, thereby improving their social and financial resilience [

43]. Fourth, community-based disaster risk reduction programs can prepare vulnerable households, including ethnic minority communities, to respond to and reduce the impact of natural disasters, improving their overall resilience [

44,

45]. Lastly, policies and programs that promote women’s economic empowerment, such as providing access to credit, training, and support for women-led businesses, can enhance the economic resilience of vulnerable households, particularly those led by women in ethnic minority communities [

46].

It is important to recognize that these interventions must be tailored to the unique needs and contexts of each community to achieve optimal effectiveness. Furthermore, it is critical to prioritize women and the poor in these programs, given their lower levels of resilience. Additional suggestions for practice include strengthening community-based organizations and involving them in the design, implementation, and monitoring of resilience-building programs. These can enhance local ownership, promote sustainability, and ensure that the programs are culturally appropriate. Additionally, policy interventions should be complemented with measures to address underlying structural issues, such as inequality, marginalization, and discrimination. For example, land and forest reform programs can help address unequal land distribution, which is a major source of vulnerability for many upland households [

13]. Finally, building partnerships between different actors, including the government, civil society organizations, and the private sector, can leverage their strengths and resources to enhance the resilience of vulnerable communities [

47,

48,

49].

In brief, the intersection of social inequality, gender roles and rights, resource scarcity, poverty, inadequate infrastructure, limited financial resources, and ineffective risk management plans is closely tied to the level and fluctuations of resilience on the ground, potentially resulting in disproportionate suffering and loss from climate variability. Addressing these disparities is crucial for promoting equality and social justice, and requires an intersectional approach in practical policies. As noted by Jones and Tanner (2015), resilience must prioritize the livelihoods of vulnerable populations and incorporate development strategies to meet the needs of the planet’s poorest and most marginalized communities [

23]. Gender-related studies are widely published, but gender issues are often not integrated into climate change policies and programs in many developing countries [

27,

46]. This lack of consideration for marginalized groups’ perspectives and experiences is due to a lack of comprehensive and reliable data on the gendered impacts of climate change, making it difficult to design effective policies and interventions. Additionally, intersectional research on climate change is still lacking [

8], resulting in gaps in understanding the experiences of marginalized communities and how climate change intersects with other forms of discrimination. This study provides a valuable contribution to gender-related research by adopting a context-specific approach to assess household resilience and offering tailored recommendations for the studied communities. The study conducted a nuanced analysis of self-assessments provided by households from two upland communities, namely, the Kinh majority and the Co Tu ethnic minority, located in the Nam Dong District, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam. Given that the study area is particularly vulnerable to climate change due to its disadvantaged economic and geographic conditions, the findings shed light on significant disparities in resilience levels among different ethnic and gender groups, offering critical insights into how policies and programs can better support disadvantaged groups and promote sustainable rural development. The study underscores the importance of addressing cultural and social norms specific to the studied communities and highlights the need to move beyond relying solely on macroeconomic data. By emphasizing the significance of enhancing financial, human, and social capitals; promoting overall well-being; and alleviating poverty, the study provides actionable recommendations for building resilience among disadvantaged groups in this specific context.

However, we recognize that the present study has certain limitations. First, it focuses primarily on two specific target groups, namely, the King majority and the Co Tu people, and thus excludes other ethnic groups, such as the Ta Oi and others, unintentionally. Second, this study lacks a meta-analysis integration of socioeconomic factors in the region, such as population growth rate or total area. Lastly, this study did not consider sensitive variables, such as social norms and customs, which can be crucial in building climate resilience in the Vietnamese rural community. Therefore, future studies should address these limitations to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the subject matter.

6. Conclusions

This study represents a groundbreaking departure from conventional macroeconomic-data-based research that typically overlooks the subjective experiences of communities and social groups in their assessments of resilience to stressors. To obtain a comprehensive understanding of household resilience, we conducted a highly nuanced analysis of self-assessments provided by 364 household heads in the Nam Dong District, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam. Our investigation focused on the two upland communities of the Kinh majority and Co Tu ethnic minority households, evaluating their resilience levels in terms of the five livelihood capitals and identifying significant disparities among different ethnic and gender groups.

Our findings reveal that women, ethnic minorities, and the poor exhibit notably lower levels of resilience to external changes caused by climate change, among other factors. This underscores the need for policies and programs designed to improve resilience and promote rural development, with an emphasis on these groups’ cultural and social norms. In particular, we recommend a focus on improving financial, human, and social capitals to increase households’ resilience to external shocks. Enhancing financial capital through off-farm income, local-resource-based initiatives, and livelihood diversification; increasing human capital by raising farmers’ awareness of climate shocks and improving education levels; and expanding social capital through greater participation in local civil society organizations to strengthen households’ social linkages can all contribute to enhancing livelihood recovery capacity.

Moreover, building resilience for disadvantaged groups must go hand in hand with promoting their overall well-being and alleviating poverty. Therefore, strategies for allocating poor households and encouraging them to actively raise their incomes should be top priorities. Tailored training programs to raise awareness among households, improving infrastructure, and enhancing institutional systems can also contribute to building resilience. Overall, our study highlights the importance of adopting a nuanced, subjective approach to assess household resilience and provides critical insights into how policies and programs can better support disadvantaged groups and promote sustainable rural development.