Abstract

The objective of this work is the development of an automated and objective identification scheme of cold fronts in order to produce a comprehensive climatology of Mediterranean cold fronts. The scheme is a modified version of The University of Melbourne Frontal Tracking Scheme (FTS), to take into account the particular characteristics of the Mediterranean fronts. We refer to this new scheme as MedFTS. Sensitivity tests were performed with a number of cold fronts in the Mediterranean using different threshold values of wind-related criteria in order to identify the optimum scheme configuration. This configuration was then applied to a 10-year period, and its skill was assessed against synoptic surface charts using statistic metrics. It was found that the scheme performs well with the dynamic criteria employed and can be successfully applied to cold front identification in the Mediterranean.

1. Introduction

Cold fronts are significant components of the weather and climate systems, and can be closely associated with extreme events. The passage of a cold front is indicated by, and associated with, substantial variations of temperature, humidity and wind. The identification of cold fronts has attracted more scientific interest than their warm counterparts because of their more discrete character and their connection with severe weather phenomena [1,2,3,4,5,6].

Despite the availability of numerical prediction and analysis models, the manual identification of fronts on weather charts is a time-consuming process that introduces a high degree of subjectivity, even for an experienced operational meteorologist [7,8]. The complexity of the task dictates that the compilation of frontal climatologies by manual methods is not feasible. Hence, there is practical and scientific interest in developing automated schemes to create such climatologies from observed data, reanalyses, and climate model outputs [8]. The advantage of automated detection methods is that they are objective, reproducible, and fast.

The majority of such objective and automated front identification methods in the literature use thermal criteria [6,9,10,11,12,13]. Most of these studies focus on large-scale fronts that develop and move across vast areas of oceans and continents. Thus, their identification is facilitated by the large scale of fronts and the homogeneity of surfaces. However, verification of these algorithms has shown that the recognition of the frontal surfaces, taking into account only temperature gradients, is inadequate in many cases for complex features [14,15]. Some of these methods are used routinely in weather forecasting [16], whereas others focus on extreme events, such as widespread fires [17]. A number of automated algorithms have been applied in order to generate frontal climatologies for southwest Western Australia [18], for the globe [7], and for the Southern Hemisphere [19,20].

Since the Mediterranean Sea is a closed basin surrounded by complex topography, its fronts tend to exhibit small spatial and temporal scales, as well as complicated kinematic and thermodynamic features during their lifetime [21]. Climatological studies focusing on the Mediterranean fronts are relatively few, and the early studies were based on subjective approaches utilising synoptic surface maps [22]. The investigation of a nine-year period (1971–1979) of daily charts [22], demonstrated that fronts appear very frequently in the Mediterranean throughout the year with maximum frequency one every seven days in winter. While identification schemes have been applied to diagnose the climatologies of cyclonic [23,24,25] and anticyclonic centers [26] in the Mediterranean, there is no corresponding application for the analysis of cold fronts.

The objective of this study was to develop and evaluate a scheme for the identification of cold frontal systems in the Mediterranean basin which is based on the Frontal Tracking Scheme (FTS) [19]. In Section 2, the scheme and the modifications performed are presented in brief, while in Section 3, typical results of the sensitivity tests are given for specific high impact cases connected with cold fronts passages over the Mediterranean. In Section 4, a statistical validation of the scheme for a decade is given and, finally, in Section 5, the main conclusions are summarized.

2. Description of the Identification Scheme

FTS was developed at The University of Melbourne, Australia [19], and has been used for the climatological study of Southern Hemisphere cold fronts. Unlike other similar schemes which use thermal criteria [7,10,16], FTS uses only wind-related criteria to identify fronts and has proved to work well compared to the other schemes. More specifically, thermal based methods are known to have difficulties identifying fronts in the areas of high temperature contrasts, such as coastal areas and regions with elevated topography [15]. Hence, the Mediterranean region would be a particularly difficult site for frontal identification using thermal variables. Furthermore, thermal based methods may not be able to reliably distinguish between cold/warm fronts [27].

FTS is based on Eulerian changes of the 10 m meridional wind component (v) which is valuable in diagnosing various aspects of frontal behavior [8,28]. The criteria for identification are [19]: (a) at a time t, grid points are flagged where the wind changes from the southwestern quadrant (westerly zonal wind u > 0, southerly meridional wind v > 0) to the northwestern quadrant (westerly zonal wind u > 0, northerly meridional wind v < 0) between subsequent time points t and (t + 6 h), (b) the change of the meridional wind dv exceeds a specific threshold value dvcrit during the same 6 h period.

The grid points which satisfy the above-mentioned criteria are flagged and a component labelling technique is applied [29]. Then, each flagged pixel is related and connected to its nearest eight neighbors, giving clusters of grid points. The location of the front is determined by the eastern edge of each cluster. As this approach is applied to all of the eastward edge points, the output is a set of latitude and longitude points which mark the location of the front. Thus, the location of the front at the time t + 6 h is given by a single series of longitude values. These values will have a stepwise character, since they represent discrete grid points. For this reason, the longitude values are treated as a simple series and smoothed by a resistant smooth method [30] appropriate for equally-spaced data. This robust statistical technique employs a set of short-window running median and running mean filters, which are successively applied multiple times to the series, to achieve adequate smoothing. Then, the obtained smoothed eastern edge determines a “mobile front”. This method is particularly suited for the detection of strongly elongated, meridionally oriented fronts, which typically extend far from a cyclone center [19].

Since FTS was developed to identify cold fronts in the oceans while the topography of the Mediterranean affects the formation and characteristics of cold fronts [31], in this study FTS is modified to better identify the position, scale and tilt of cold fronts in the Mediterranean. From the records of the Hellenic National Meteorological Service, twenty cases of cold fronts are selected that entered Mediterranean from different regions (e.g., Atlantic, North Africa, northern Europe) or formed in different parts of the Mediterranean (Western, Central and Eastern) during different months throughout the year, having caused intense precipitation.

The initial criterion used in MedFTS is that the zonal component u is westerly both at t and t + 6 h and the meridional wind changes sign from positive to negative. Then, sensitivity tests were performed on the other wind related criteria. First, sensitivity tests are made on the criterion of meridional wind change within the 6 h time step (dv), in order to find the optimum threshold value of the meridional wind magnitude change dvcrit. Second, instead of using the change of the meridional wind component (dv), the shift of the vector wind direction is employed during a 6 h period (dφ), where φ = arctan (v/u) and a specific minimum threshold value dφcrit is also investigated. This criterion is examined to better identify zonally elongated cold fronts and at the same time, to filter out erroneously identified front segments. Third, an additional criterion of the magnitude of vector wind |U| exceeding a specific critical threshold |U|crit in each cluster of grid points is added to optimise the scheme, considering the operational experience of forecasters that the intensity of the northwesterly wind is significant behind the cold front. This criterion allows the discarding of shallow fronts.

3. Sensitivity Tests

For the twenty selected cases, ECMWF Re-Analysis (ERA)-Interim datasets of zonal u and meridional v wind components at the near-surface level (10 m) on a 0.5° × 0.5° resolution are used [32]. This high resolution was chosen in order to obtain a better representation of the small-scale fronts appearing in the Mediterranean region. The scheme results are compared with the surface analyses produced by the UK MetOffice, archived by www2.wetter3.de, available every 6 h. Furthermore, for the validation of the results, MSG IR 12.0 μm satellite images, available from the Hellenic National Meteorological Service, are employed. We restrict ourselves here to showing results for the case of 7–10 November 2016 that included two extended tilted cold fronts that travelled across Mediterranean. However, the results were consistently investigated and validated for the other cases. The tests are performed following the rationale described in Section 2.

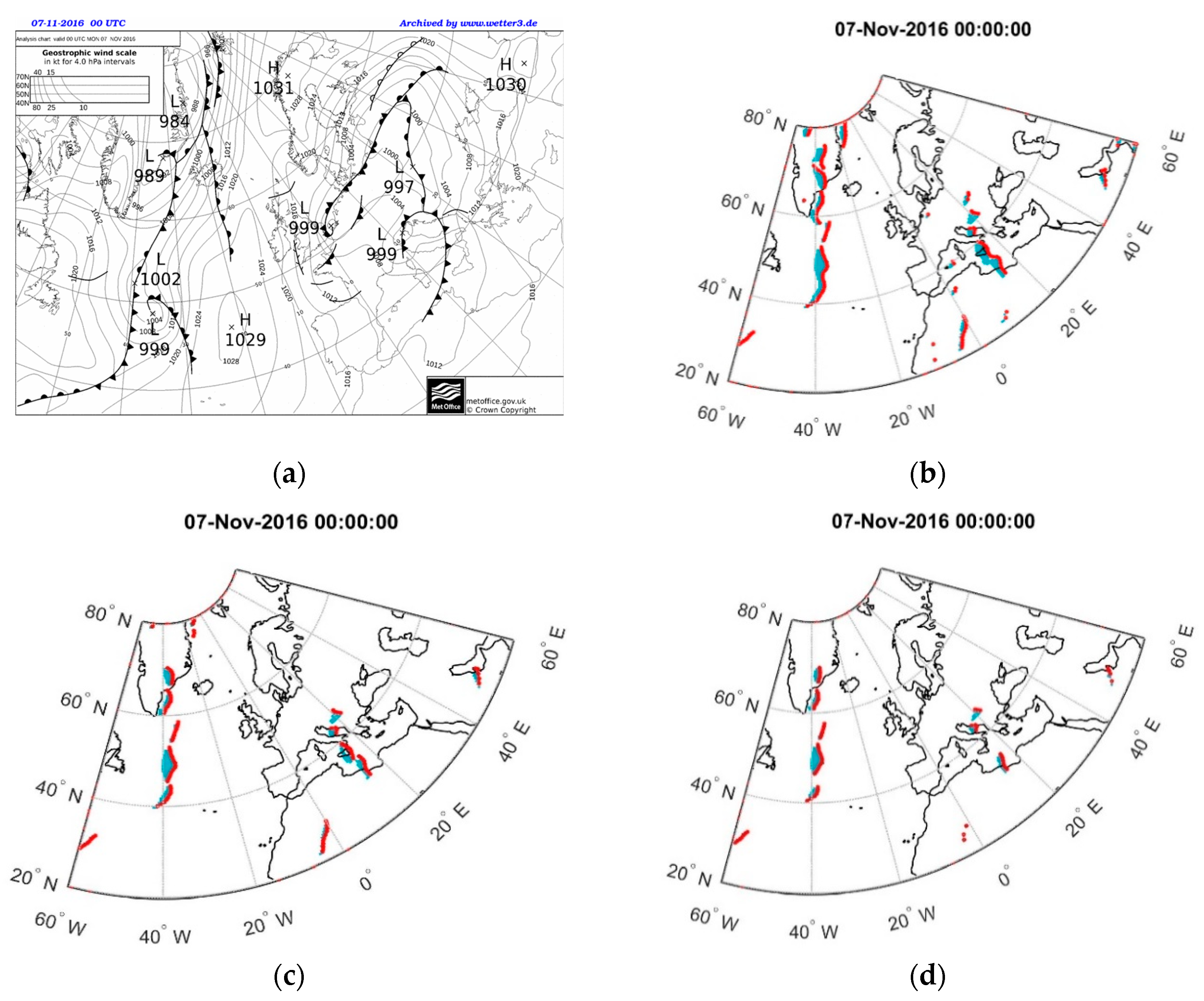

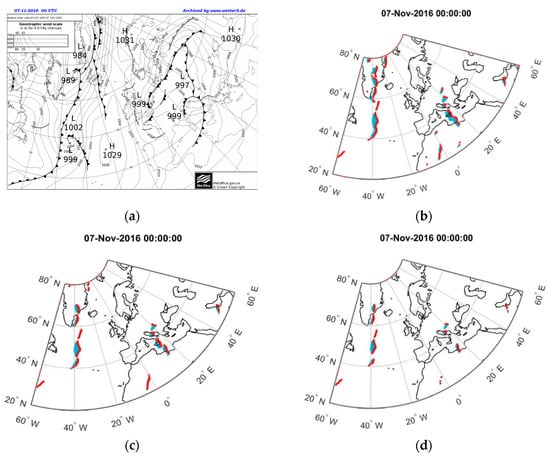

First, the critical values of the 6 h meridional wind change dvcrit was explored. An initial threshold value dvcrit = 2 m s−1 was employed, as suggested by [19] in the initial version of FTS. Then, the scheme was employed for different values of dvcrit increasing by 1 m s−1. Figure 1a shows the synoptic situation of 7 November 2016, 00:00 UTC. In Figure 1b, the identified fronts are depicted (red lines) for the same day and hour for dvcrit = 3 m s−1. In the same Figure, the light blue regions show the areas where the wind shift criterion is satisfied.

Figure 1.

(a) Synoptic surface chart over the area of interest at 00:00 UTC 7 November 2016, and identified fronts for (b) dvcrit = 3 m s−1, (c) dvcrit = 5 m s−1, and (d) dvcrit = 7 m s−1. The red lines show the identified fronts, whereas the areas where the wind shift criterion is satisfied are depicted with the light blue color.

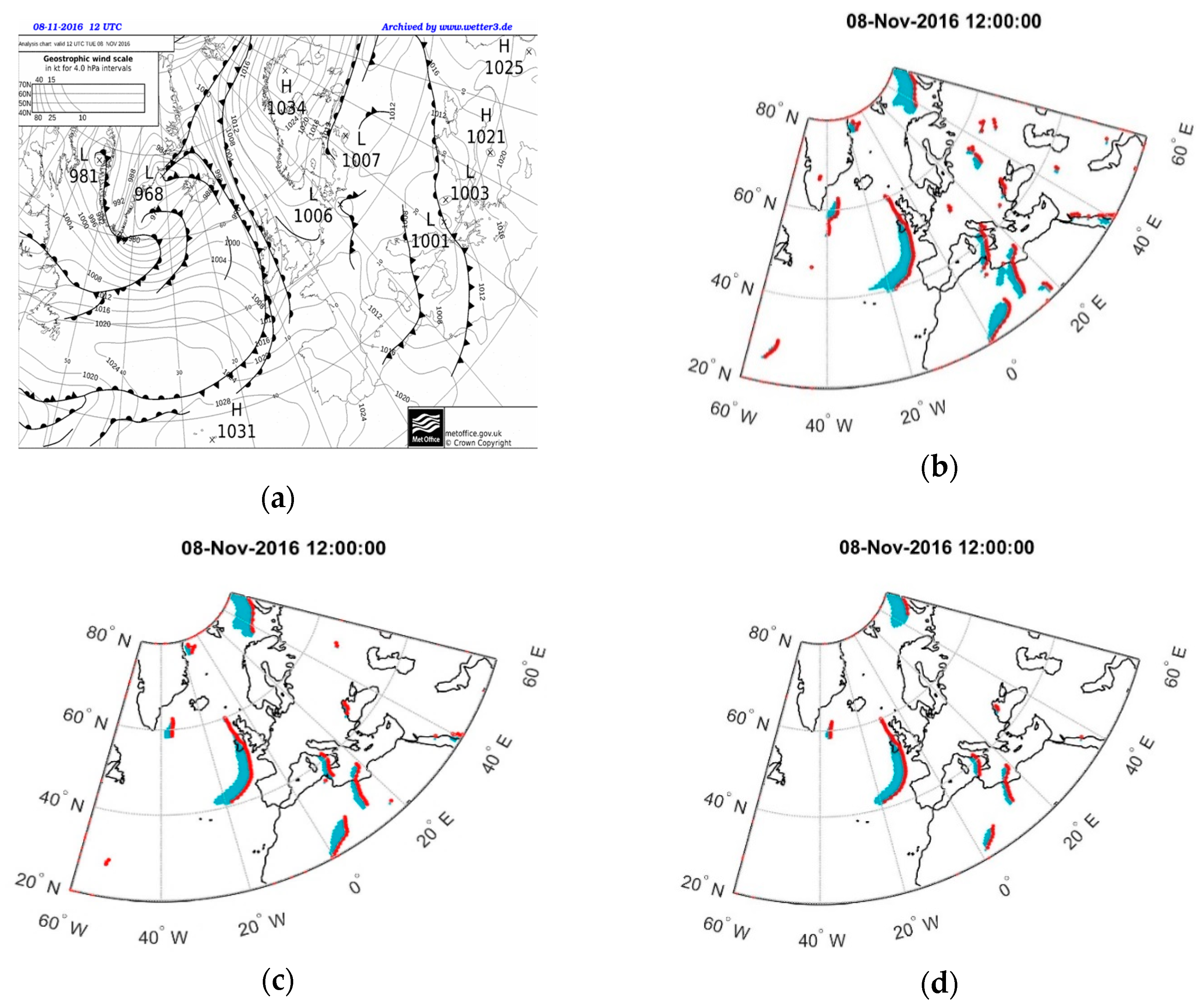

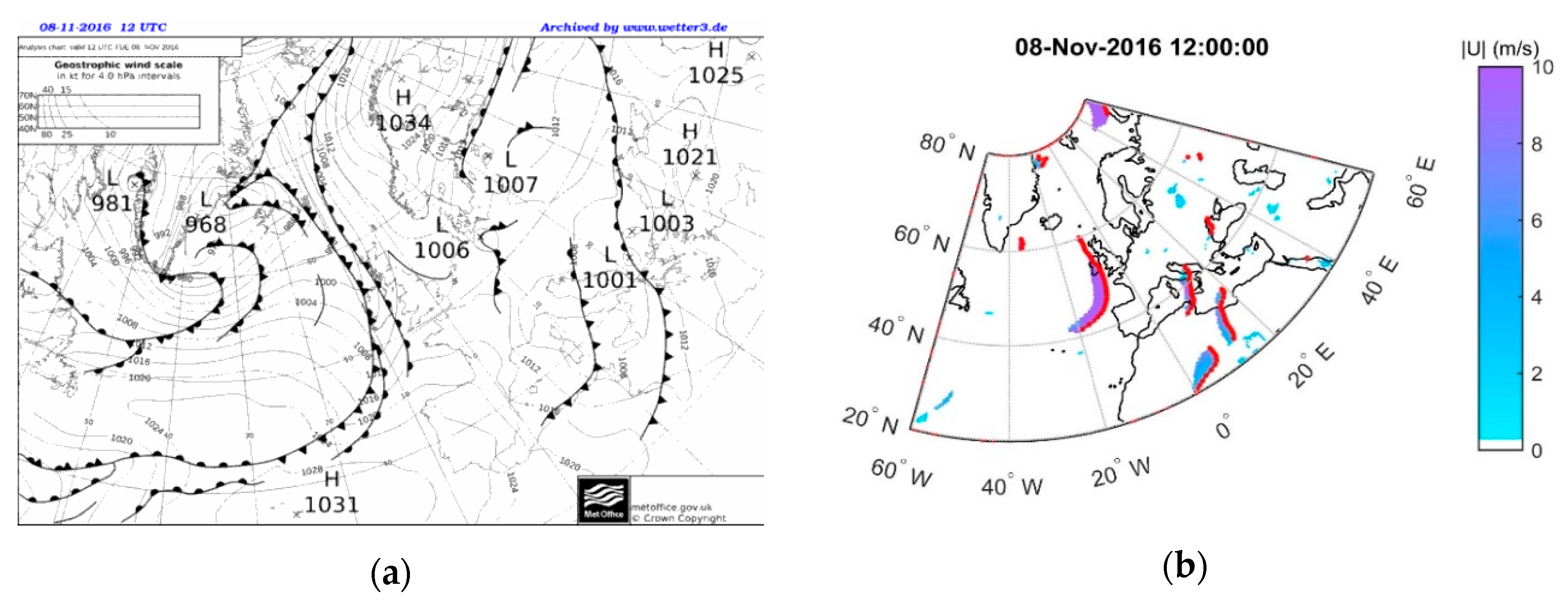

A comparison of Figure 1a,b reveals that the scheme succeeds in identifying fronts over the Atlantic. However, in the Mediterranean, its performance is somewhat lower: although it identifies correctly the main cold front over Italy, this is segmented over the Adriatic Sea while other frontal fragments are produced which do not exist in the synoptic analysis. For larger values of dvcrit of 4 and 5 m s−1, the erroneous front identifications show a tendency to diminish (Figure 1c). However, when dvcrit exceeds the value of 6 m s−1, the existing fronts incline to be broken into smaller fragments (Figure 1d). Therefore, moderate values of dvcrit ranging between 4–6 m s−1 seem to best represent Mediterranean cold fronts. Similar results were derived for the following hours. Figure 2 shows the results for 8 November 2016 at 12:00 UTC.

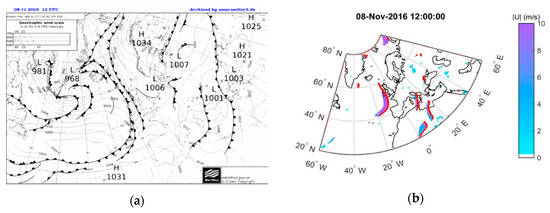

Figure 2.

(a) Synoptic surface chart over the area of interest at 12:00 UTC 8 November 2016, and identified fronts for (b) dvcrit = 2 m s−1, (c) dvcrit = 4 m s−1, and (d) dvcrit = 6 m s−1. The red lines show the identified fronts, whereas the areas where the wind shift criterion is satisfied are depicted with the light blue color.

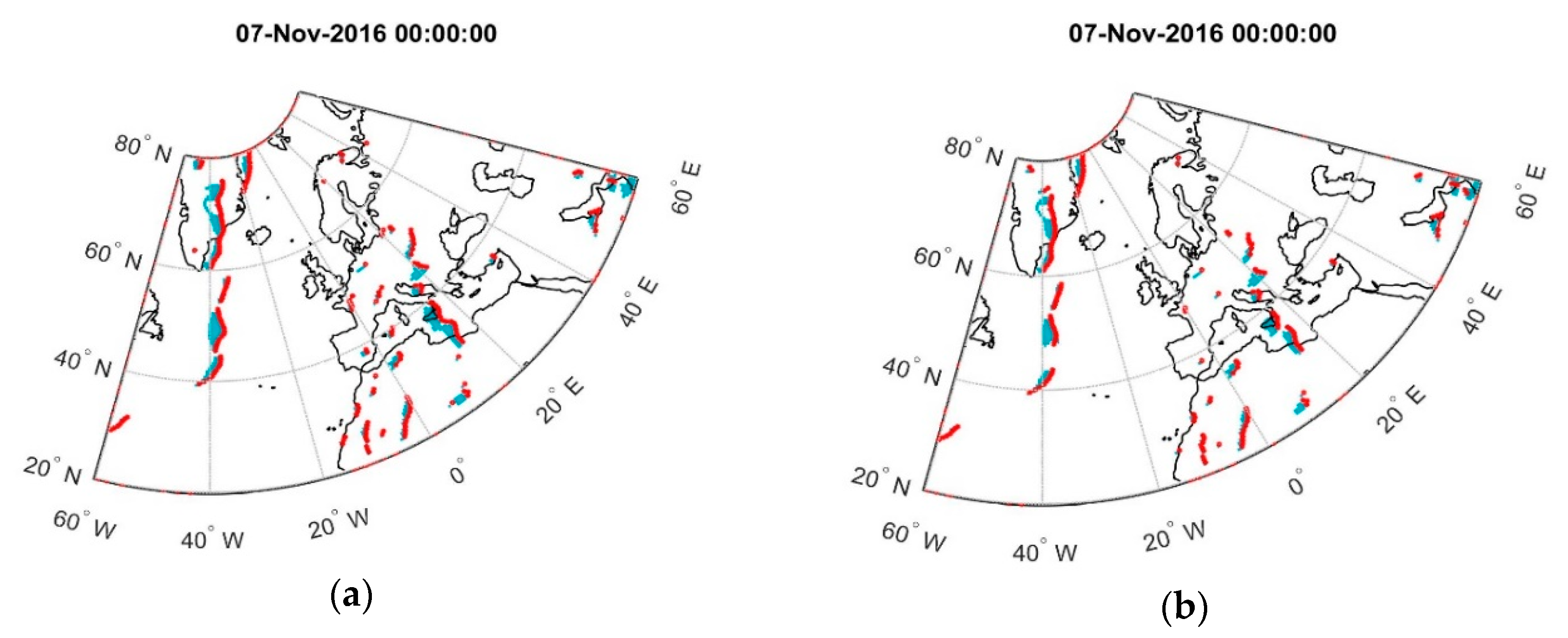

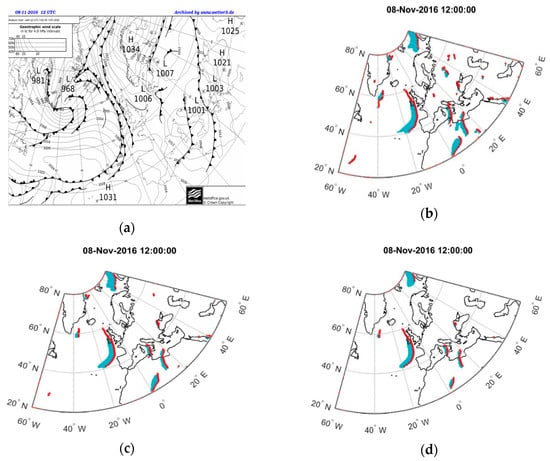

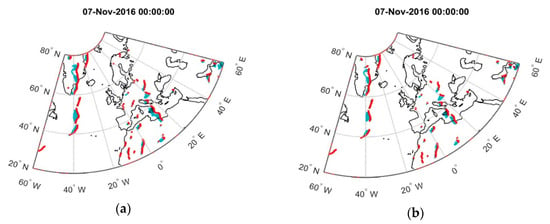

Since the analysed Mediterranean fronts are not purely meridionally elongated, but they rather tend to assume a more zonal orientation, the 6 h change of the total wind direction dφ is explored instead of the change of the meridional wind magnitude. It should be noted that this criterion was found helpful in identifying cold fronts that present zonal orientation in the beginning of their life [31] and the criterion on dv might not be able to properly identify them. The scheme was tested for different values of dφcrit starting from 20°, with steps of 10°. In Figure 3, the identified fronts are depicted for 7 November 2016, 00:00 UTC, for (a) dφcrit = 30° and (b) dφcrit = 50°. A comparison with the synoptic analysis in Figure 1a shows that the scheme indeed represents the front over Italy when dφcrit = 30°. However, it can be appreciated that using solely the dφ criterion, several erroneously identified fronts are obtained. Moreover, for dφcrit = 50°, the front over Italy is mistakenly broken into smaller fragments. Similar results were obtained for dφcrit > 40° and the best representation of fronts was obtained for dφcrit = 30° in most cases. To effectively filter out the erroneously identified frontal objects without losing the spatial continuity of the correctly identified fronts, the value dφcrit = 30° is adopted.

Figure 3.

Identified fronts at 00:00 UTC 07 November 2016, for (a) dφcrit = 30° and (b) dφcrit = 50°. The red lines show the identified fronts, whereas the areas where the wind shift criterion is satisfied are depicted with the light blue color.

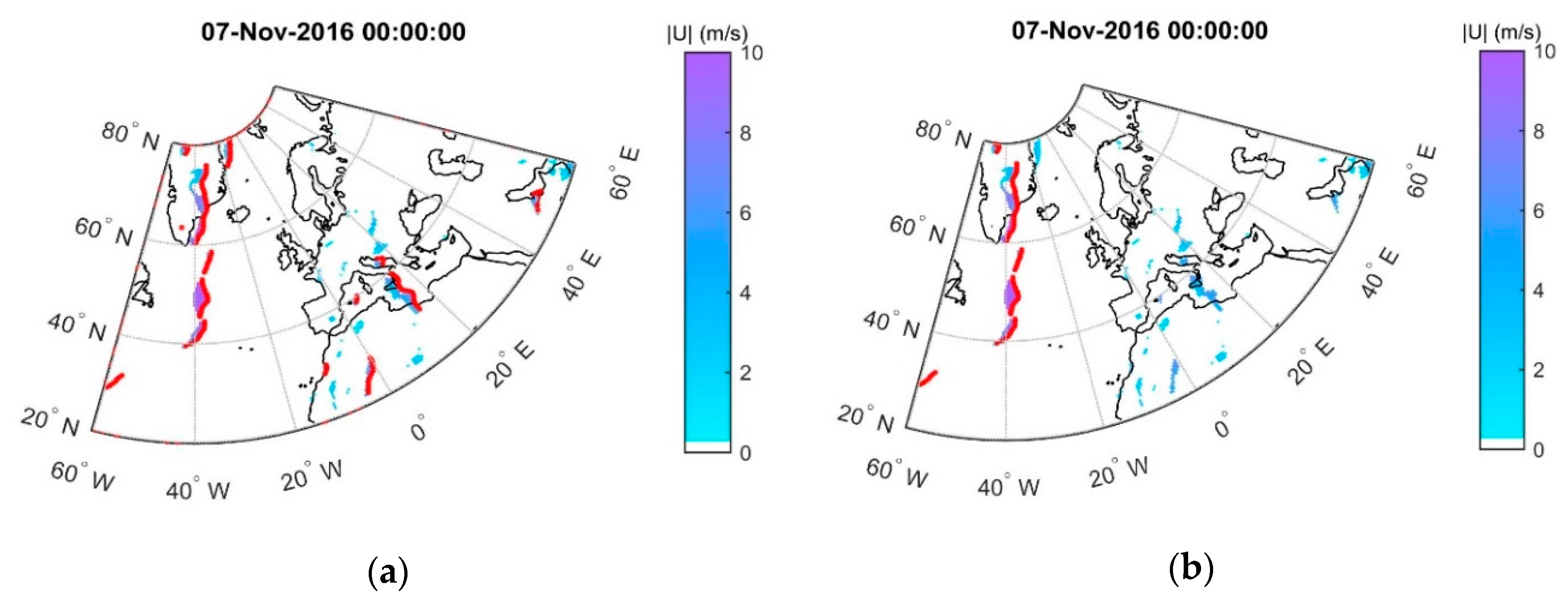

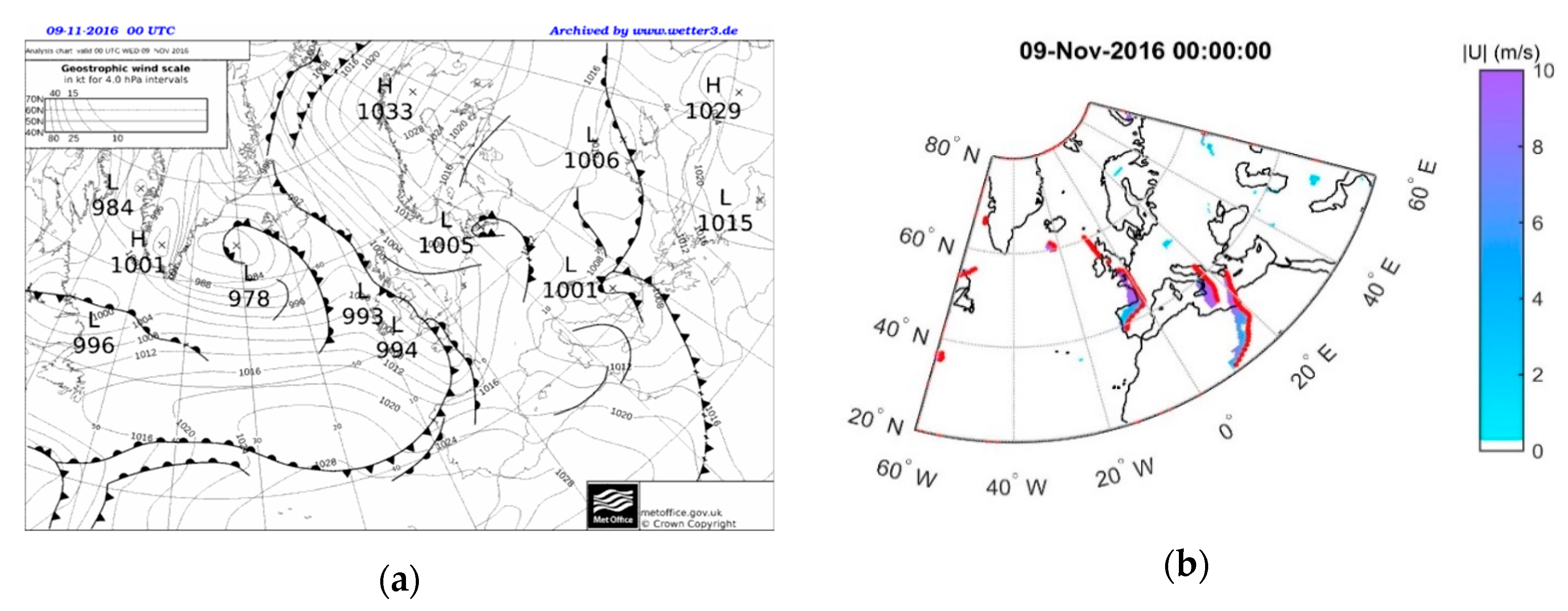

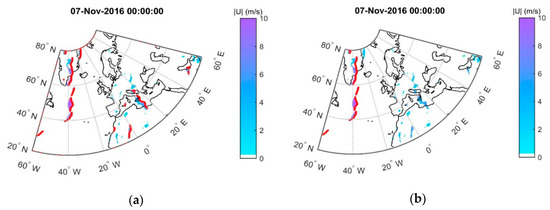

The use of the dφ criterion alone is not adequate, since it may lead to mistakenly identified fronts in cases when, at t + 6 h, the wind is weak or there is calm. For this reason, another criterion that we apply is that the maximum magnitude of the vector wind is above a threshold value |U|crit. It should be noted that apart from filtering out mistaken identifications, this criterion also helped in identifying cold fronts entering from North Africa and distorted cold fronts in the Central Mediterranean that rejuvenated when entering the Aegean Sea. To find the optimum value of |U|crit, values between 0 and 10 m s−1 were tested. Figure 4 depicts the results of the scheme on 7 November 2016 00:00 UTC for (a) |U|crit = 5 m s−1 and (b) |U|crit = 7 m s−1. Red lines represent the identified fronts, whereas colored areas show the magnitude of the total wind |U| at the grid points where the dφ criterion is met. It is clear that a value of |U|crit = 5 m s−1 effectively filters out spurious front identifications, while a larger value (e.g., |U|crit = 7 m s–1) erroneously filters out the front over Italy. From the above sensitivity tests, the combination of dφcrit = 30° and |U|crit = 5 m s−1 seems to best represent cold fronts in the Mediterranean at each following synoptic time (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Similar results were derived for the other selected cases under a variety of synoptic environments. It should be noted that based on these dynamic criteria, warm frontal structures are not identified.

Figure 4.

Identified fronts at 00:00 UTC 7 November 2016, for dφcrit = 30°, (a) |U|crit = 5 m s−1 and (b) |U|crit = 7 m s–1. Red lines represent the identified fronts, whereas colored areas show the magnitude of the total wind |U| at the grid points where the dφ criterion is met.

Figure 5.

(a) Synoptic surface chart at 12:00 UTC 08 November 2016, and (b) identified fronts for dφcrit = 30° and |U|crit = 5 m s–1. Red lines represent the identified fronts, whereas colored areas show the magnitude of the total wind |U| at the grid points where the dφ criterion is met.

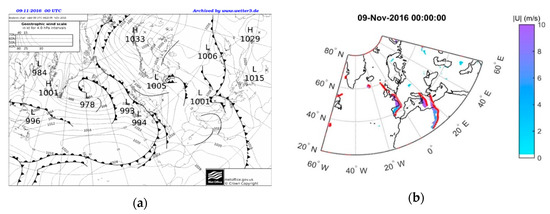

Figure 6.

(a) Synoptic surface chart over the area of interest at 00:00 UTC 9 November 2016, and (b) identified fronts for dφcrit = 30° and |U|crit = 5 m s–1. Red lines represent the identified fronts, whereas colored areas show the magnitude of the total wind |U| at the grid points where the dφ criterion is met.

In summary, in order to identify a front in our MedFTS scheme we require: (a) the zonal component u is westerly both at t and t + 6 h, (b) the meridional wind changes sign from positive to negative, (c) the directional shift of the wind (dφ) exceeds the threshold of dφcrit = 30° and (d) the magnitude of the vector wind |U| is greater than |U|crit = 5 m s−1. It should be noted that the initial criterion of dv> dvcrit used in FTS has been replaced by both the criteria of dφ > dφcrit and |U| > |U|crit.

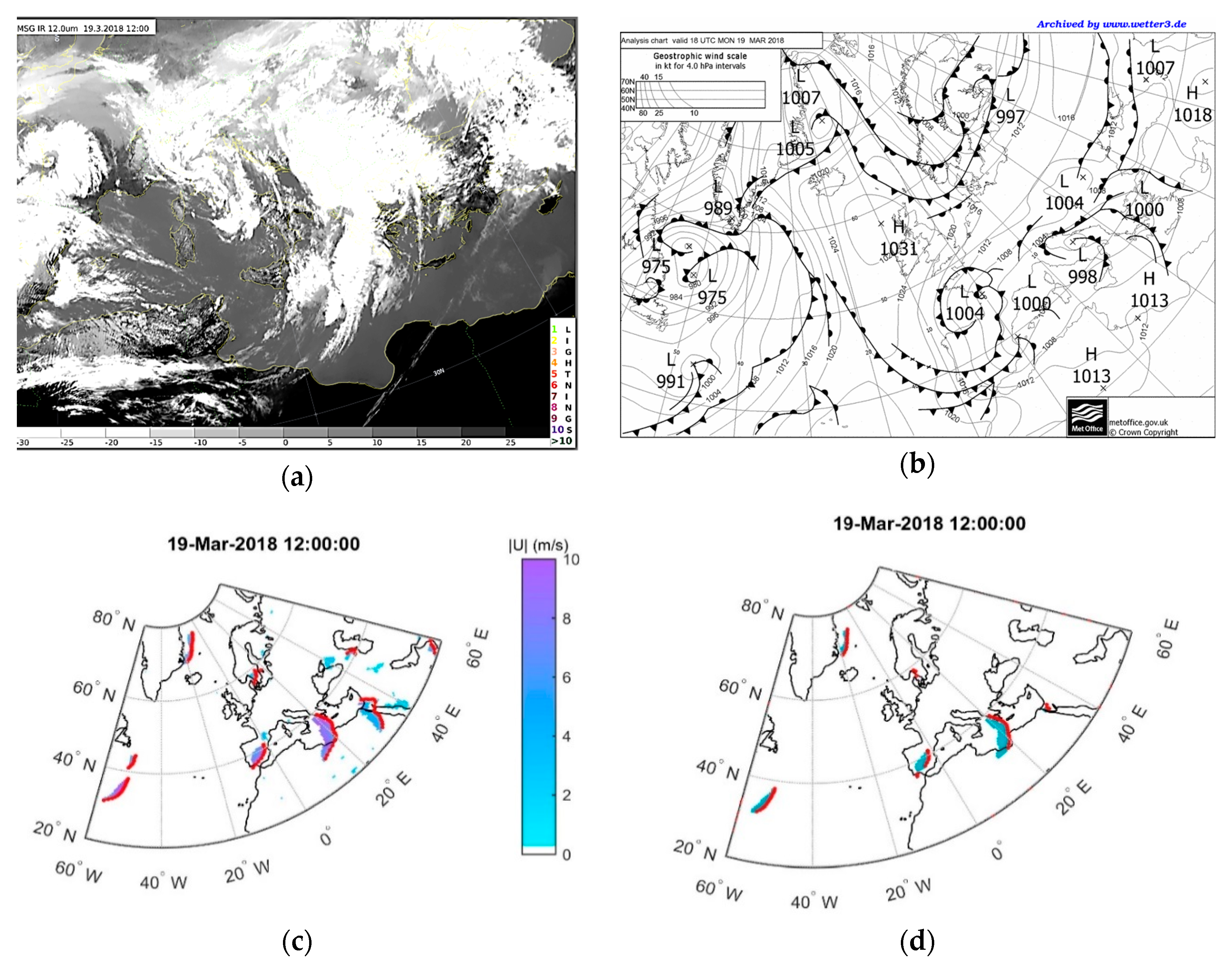

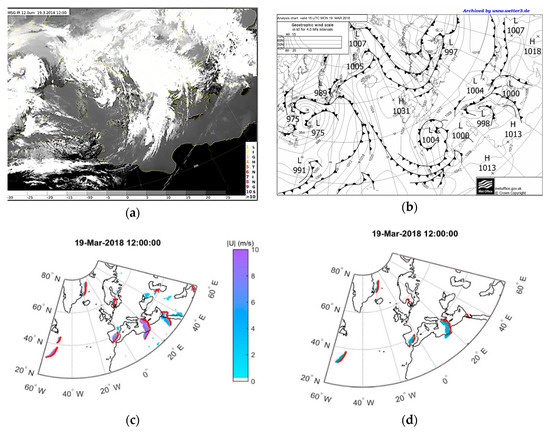

In order to check the performance of MedFTS, the results for 19 March 2018 at 12 UTC is demonstrated in Figure 7 which included a cold front that developed over Tunisia and affected Greece after rejuvenation and a zonally oriented cold front over the Iberian Peninsula that entered from the Atlantic and moved towards western Mediterranean. Figure 7a,b shows that the surface analysis agrees well with the satellite image for the cold front over Greece. The scheme correctly represents the location and orientation of the fronts at this specific time (Figure 7c), avoiding many erroneous identifications before the use of the |U|crit. The zonally elongated front over the Iberian Peninsula is also identified correctly by the scheme (Figure 7c) along with its subsequent evolvement. Figure 7d presents the results when the dv criterion is solely used. From the comparison between Figure 7c,d becomes evident that the zonal front over the Iberian is not properly identified with the dv criterion. Therefore, it is suggested that the successful identification of this front is mainly attributable to the combination of dφcrit and |U|crit criteria.

Figure 7.

(a) Satellite image (IR 12μm) of the Mediterranean sea at 19 March 2018, 12:00UTC, (b) synoptic surface chart over the area of interest at the same time, (c) identified fronts for dφcrit = 30° and |U|crit = 5 m s–1. Red lines represent the identified fronts, whereas colored areas show the magnitude of the total wind |U| at the grid points where the dφ criterion is met. (d) Respective results for the case of solely the dv criterion for dvcrit = 6 m s−1.

4. Statistical Validation

After the above modifications, the new MedFTS scheme was applied for a ten-year period (2007–2016) in order to validate its ability in identifying Mediterranean cold fronts on climatological basis. The number of the cold fronts passing over Greece was counted for the specific synoptic hour of 00:00 UTC. Then, the results were validated against synoptic analyses obtained from Deutscher Wetterdienst, with the aid of statistical indices (Table 1). It should be noted that the statistical validation handles the occurrence of a cold front as a two-fold categorical variable, and therefore if two fronts appear at the same time over the examined area in the analysis or in the scheme, only one is counted in the total number. Due to the limited geographic area of the examined region, the appearance of more than one front is an extremely rare event and does not affect the obtained results.

Table 1.

Definition of statistic indices used for the comparison of the fronts identified by the algorithm and the fronts appearing in the synoptic charts.

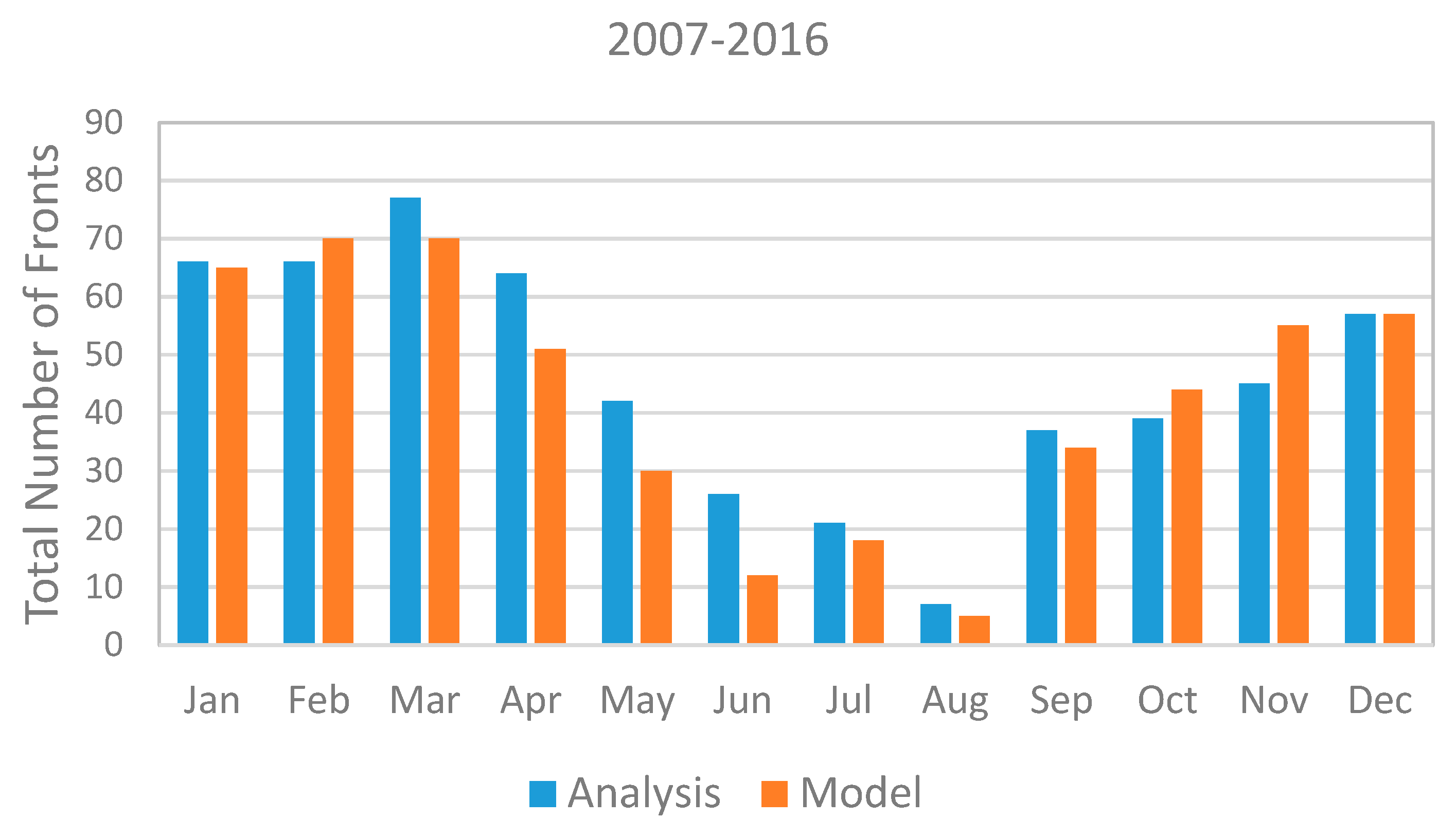

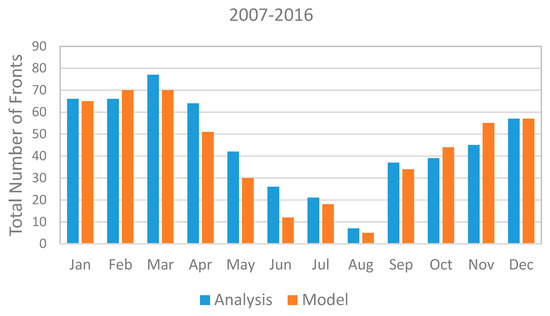

The total number of the cold fronts identified by the scheme was a + b = 511, which is slightly lower than the corresponding number identified from the charts (a + c = 547). From Figure 8 we see that there is excellent agreement between the monthly frontal frequencies in the two datasets, albeit with a scheme underestimation in spring and summer and overestimation in autumn and winter. Furthermore, the scheme succeeds in capturing the intra-annual variation of the frequency of cold fronts, in agreement with the results of [22]. The vast majority of the simulated cold fronts is observed during the cold period of the year, from November to March, peaking in February and March. The frequency declines after April with minimum in August due to the predominance of anticyclonic circulation during summer over the Eastern Mediterranean [26].

Figure 8.

Mean annual cycle of the number of cold fronts identified by the MedFTS (model) and the synoptic charts (analysis) over Greece for the period 2007–2016.

Furthermore, using the indices of Table 1, we calculated the success metrics described in Table 2, taken from [33] and given in Table 3. It can be seen that the scheme succeeded in identifying correctly the bulk of fronts in synoptic charts (hits) while it correctly rejected the vast majority of the fronts that did not appear in the synoptic charts (correct rejection). On the contrary, the number of false alarms and misses are comparatively smaller. It becomes also evident that the false alarms (b) are slightly more than the misses (c).

Table 2.

Definition of the statistical metrics used of the validation of the algorithm’s capability.

Table 3.

Values of the indices of Table 1, as they are counted for the decade 2007–2016.

Table 4 gives the values obtained for the metrics of Table 2. It can be seen that the value of FBI is almost equal to the perfect score 1, suggesting that the total number of the fronts in the scheme (a + b) is almost equal with the total number of fronts appearing in synoptic charts (a + c). Therefore, the scheme is unbiased, without apparent overestimation or underestimation of the front frequency appearing in the charts. Furthermore, POD was found of 85% and FAR of about 20%, suggesting satisfactory detection of the observed fronts with limited false identifications. Besides, Critical Success Index (CSI) presents high value (0.701), taking into account both incorrectly identified fronts and unidentified fronts. Since CSI is somewhat sensitive to the climatology of the event, the Equitable Threat Score (ETS) is also used, providing comparable value.

Table 4.

Values of the metrics that are defined in Table 2 for the decade 2007–2016.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the University of Melbourne Frontal Tracking Scheme (FTS), a front tracking algorithm based solely on wind related criteria that was employed in Southern Hemisphere, was appropriately modified to identify cold fronts in the Mediterranean, a closed basin with complex topography. It was then used to compile a climatology of these features. The modified scheme (named MedFTS) employs two new criteria, i.e., total wind direction change and total wind magnitude, to better identify the position and tilt of a Mediterranean cold front. Different threshold values of the combined criteria were tested for 20 different cases of cold fronts in the Mediterranean and an optimum selection of critical values was obtained.

It was found that the total wind shift, along with the wind magnitude, accounts for good representation of different types of cold fronts in the Mediterranean throughout the year. Therefore, in order for the Mediterranean cold fronts to be identified, not only the wind shift is required but a sufficient wind magnitude as well. Since no thermodynamic criteria has been included in this scheme, it is implied that wind shift is a prerequisite for the transition of a baroclinic zone to an organised cold front in the Mediterranean, confirming the experience of operational forecasters that, if there is no wind component at the upper levels perpendicular to the low level baroclinic zone, the formation of the frontal zone is inhibited [34]. This wind shift is mostly related with upper level disturbances, approaching a pre-existing area of enhanced low level temperature gradients [35].

Considering the climatological component of the scheme, a statistical validation of its results referring to the frequency of cold fronts passing over Greece for a decade was performed against results derived manually from synoptic analyses. It was found that the total frequency of the identified cold fronts agreed very well with the frequency of the fronts identified from synoptic analyses over Greece. Furthermore, the scheme succeeded in capturing the inter-monthly variations of the frequency of cold fronts. The employment of statistical metrics, considering the front as a two-fold categorical variable, confirms the satisfactory performance of the MedFTS on a climatological basis.

We are exploring the value of including thermodynamic and moisture information into the MedFTS, although we are aware that these are not without problems and weaknesses [36]. However, we have seen that with the appropriate modifications for the Mediterranean region, the dynamically-based FTS can be successfully applied to cold front identification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.F. and J.K.; methodology, I.S. and I.R.; software, E.B., I.S., I.R.; validation, E.B. and J.K.; formal analysis, E.B., M.H.; investigation, E.B. and M.H.; data curation, M.H., J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B., H.F., M.H.; writing—review and editing, E.B., H.F., M.H.; visualization, E.B.; supervision, H.F.

Funding

This work has been partly funded by the Greek Academy of Athens under a PhD scholarship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Anderson, R.; Boville, B.W.; McClellan, D.E. An operational frontal contour-analysis model. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1955, 81, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catto, J.L.; Pfahl, S. The importance of fronts for extreme precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 10791–10801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godson, W.L. Synoptic properties of frontal surfaces. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1951, 77, 633–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.E. On the concept of frontogenesis. J. Meteorol. 1948, 5, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherhag, R. Neue Methoden der Wetteranalyse und Wetterprognose; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1948; p. 424. [Google Scholar]

- Taljaard, J.J.; Schmitt, W.; van Loon, H. Frontal analysis with application to the Southern Hemisphere. Notos 1961, 10, 25–58. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, G.; Reeder, M.J.; Jakob, C. A global climatology of atmospheric fronts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L04809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, P.; Keay, K.; Pook, M.; Catto, J.; Simmonds, I.; Mills, G.; McIntosh, P.; Risbey, J.; Berry, G. A Comparison of Automated Methods of Front Recognition for Climate Studies: A Case Study in Southwest Western Australia. Mon. Weather Rev. 2014, 142, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewson, T.D. Objective fronts. Meteorol. Appl. 1998, 5, 37–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, G.; Jakob, C.; Reeder, M. Recent global trends in atmospheric fronts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L21812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catto, J.; Raveh-Rubin, S. Climatology and dynamics of the link between dry intrusions and cold fronts during winter. Part I: Global climatology. Clim. Dyn. 2019, 53, 1873–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, R.J.; Clarke, L.C. Experiments in numerical objective frontal analysis. Mon. Weather Rev. 1965, 93, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.C.; Renard, R.J. The U.S. Navy numerical frontal analysis scheme: Further development and limited evaluation. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1966, 5, 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, G.L.; Reeder, M.J.; Smith, R.K. The diurnal evolution of cold fronts in the Australian subtropics. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2009, 135, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemm, S.; Rudeva, I.; Simmonds, I. Extratropical fronts in the lower troposphere–global perspectives obtained from two automated methods. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 141, 1686–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewson, T.D. Diminutive Frontal Waves—A Link between Fronts and Cyclones. J. Atmos. Sci. 2009, 66, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, G.A. A re-examination of the synoptic and mesoscale meteorology of Ash Wednesday 1983. Aust. Meteorol. Mag. 2005, 54, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, P.; Pook, M.; Risbey, J.; Hope, P.; Wang, G.; Alves, O. Australia’s Regional Climate Drivers. CAR6 Final Rep. Land Water Aust. 2008, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds, I.; Keay, K.; Bye, J.A.T. Identification and climatology of southern hemisphere mobile fronts in a modern reanalysis. J. Clim. 2012, 25, 1945–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudeva, I.; Simmonds, I. Variability and Trends of Global Atmospheric Frontal Activity and Links with Large-Scale Modes of Variability. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 3311–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumen, W. Propagation of fronts and frontogenesis versus frontolysis over orography. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 1992, 48, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flocas, A.A. The annual and seasonal distribution of fronts over central-southern Europe and the Mediterranean. J. Climatol. 1984, 4, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flocas, H.A.; Simmonds, I.; Kouroutzoglou, J.; Keay, K.; Hatzaki, M.; Asimakopoulos, D.N.; Bricolas, V. On cyclonic tracks over the Eastern Mediterranean. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 5243–5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campins, J.; Genovés, A.; Jansà, A.; Guijarro, J.A.; Ramis, C. A catalogue and a classification of surface cyclones for the Western Mediterranean. Int. J. Climatol. 2000, 20, 969–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouroutzoglou, J.; Flocas, H.A.; Keay, K.; Simmonds, I.; Hatzaki, M. Climatological aspects of explosive cyclones in the Mediterranean. Int. J. Climatol. 2011, 31, 1785–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzaki, M.; Flocas, H.A.; Simmonds, I.; Kouroutzoglou, J.; Keay, K.; Rudeva, I. Seasonal aspects of an objective climatology of anticyclones affecting the Mediterranean. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 9272–9289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, R.; Czaja, A.; Seo, H. A simple diagnostic for the detection of atmospheric fronts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 4351–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Piva, E.; Gan, M.A.; Rao, V.B. Energetics of winter troughs entering South America. Mon. Weather Rev. 2010, 138, 1084–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAndrew, A. An Introduction to Digital Image Processing with MATLAB; Course Technology Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; p. 528. [Google Scholar]

- Velleman, P.F.; Hoaglin, D.C. Applications, Basics and Computing of Exploratory Data Analysis; Duxbury Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkner, J.; Sprenger, M.; Schwenk, I.; Schwierz, C.; Dierer, S.; Leuenberger, D. Detection and climatology of fronts in a high-resolution model reanalysis over the Alps. Meteorol. Appl. 2010, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dee, D.P.; Uppala, S.M.; Simmons, A.J.; Berrisford, P.; Poli, P.; Kobayashi, S.; Andrae, U.; Balmaseda, M.A.; Balsamo, G.; Bauer, P.; et al. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: Configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 137, 553–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, D. Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences, 2nd ed.; International Geophysics Series; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; Volume 91, Chapter 7 (Forecast Verification). [Google Scholar]

- Bader, M.J.; Forbes, G.S.; Grant, J.R.; Lilley, R.B.E.; Waters, A.J. Images in Weather Forecasting: A Practical Guide for Interpreting Satellite and Radar Imagery; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, F. Real front or baroclinic trough? Weather Forecast. 2005, 20, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudeva, I.; Simmonds, I.; Crock, D.; Boschat, G. Midlatitude fronts and variability in the Southern Hemisphere tropical width. J. Clim. 2019, 32, 8243–8260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).