Thrust Measurement of an Integrated Multi-Sensor Micro-Newton Cold Gas Thruster

Abstract

1. Introduction

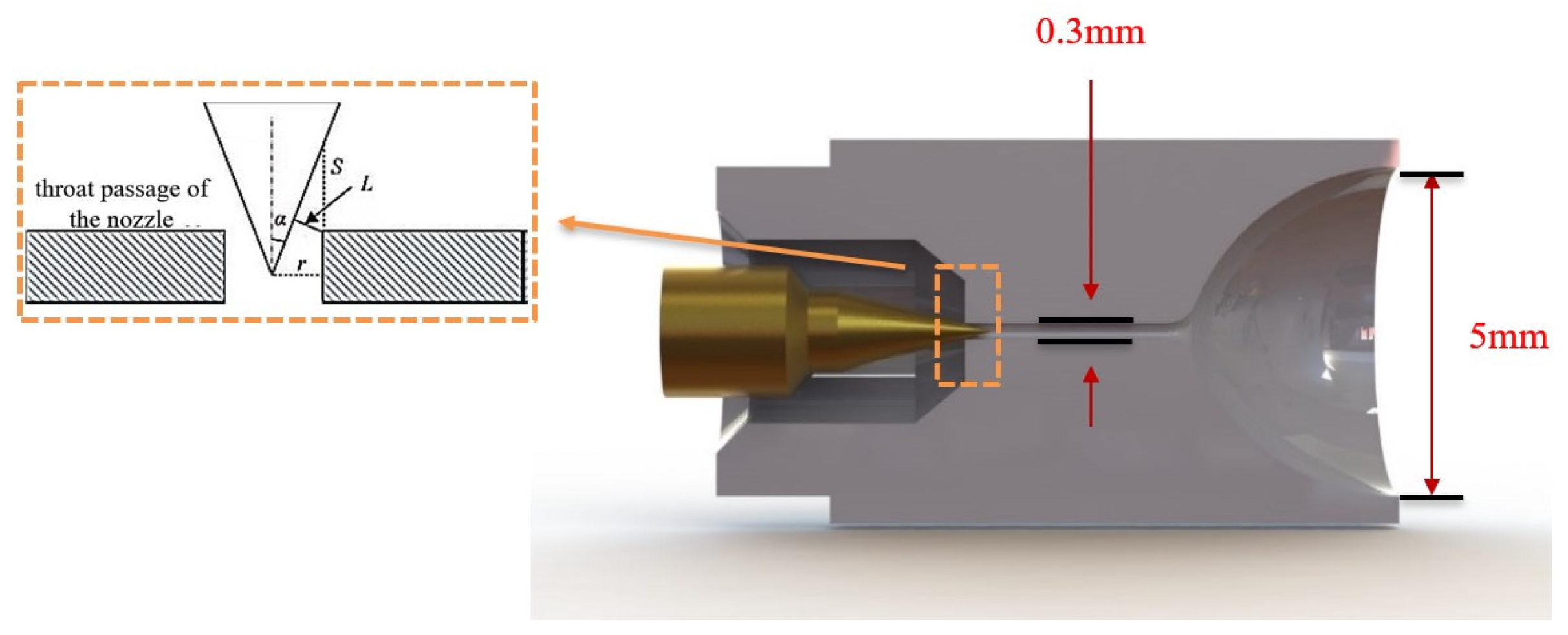

2. Principle and Composition of Cold Gas Thruster

2.1. Principle of Thruster

2.2. Composition of Thruster

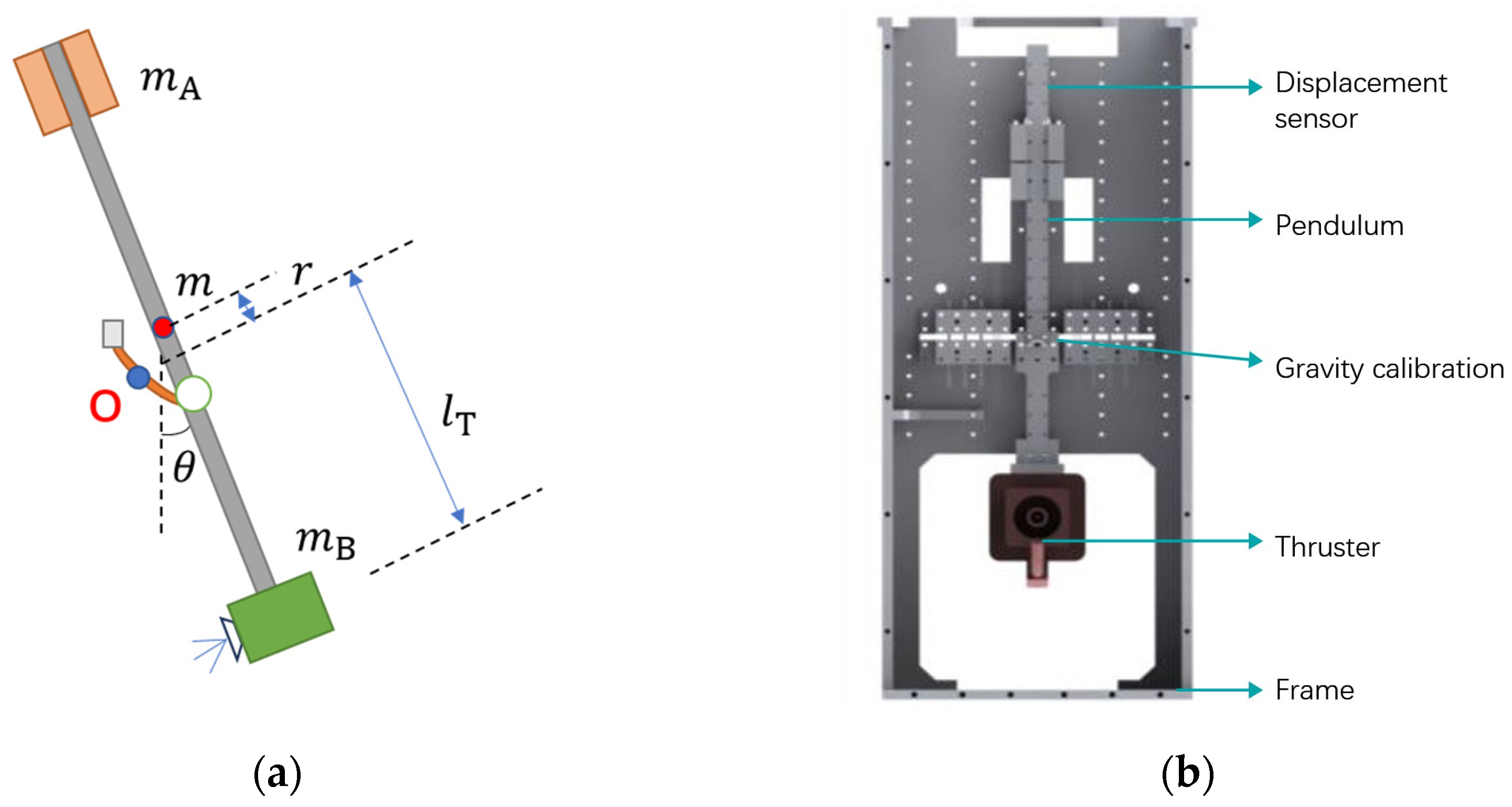

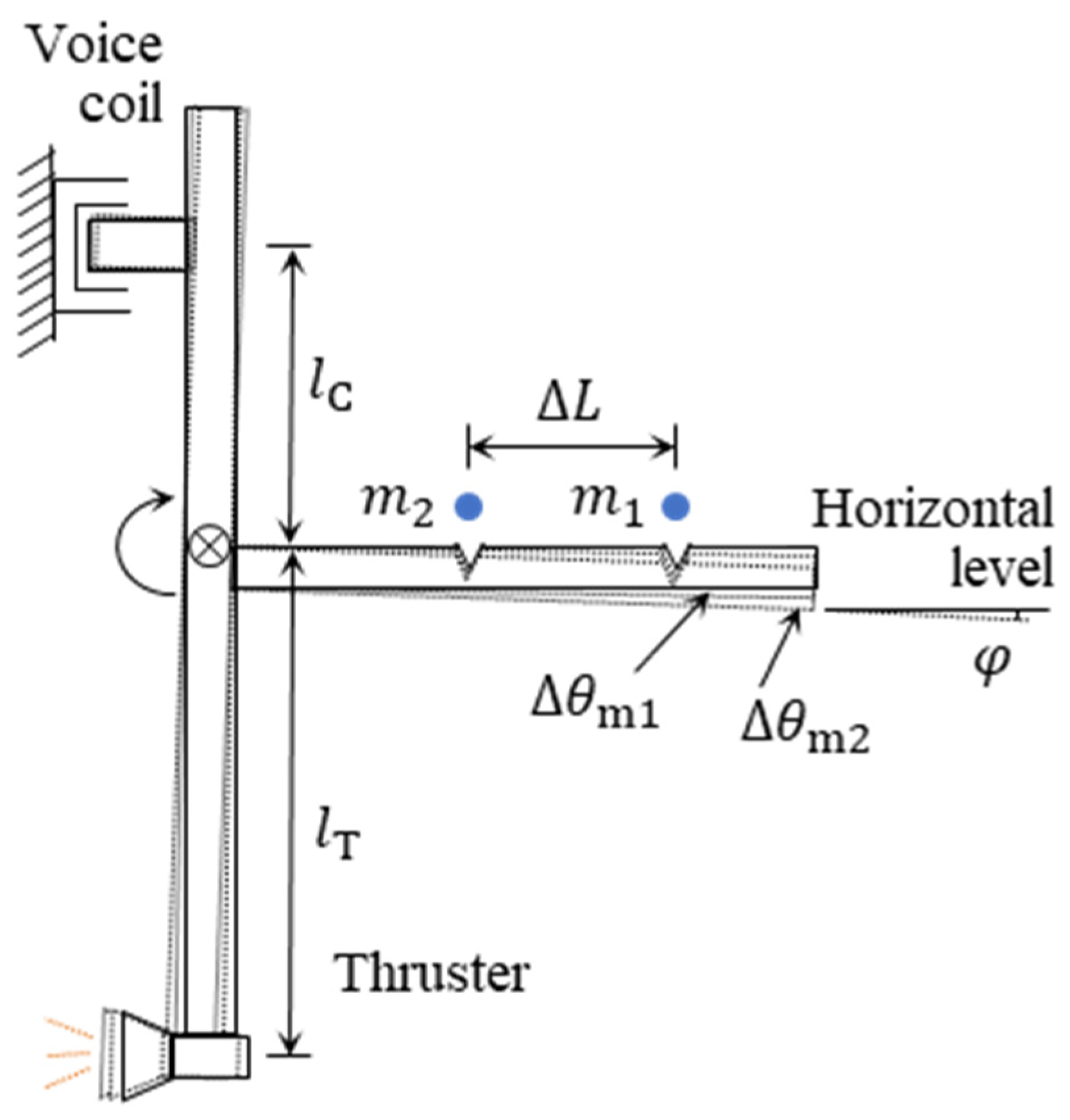

3. Thrust Measurement Principle

3.1. Measurement Principle

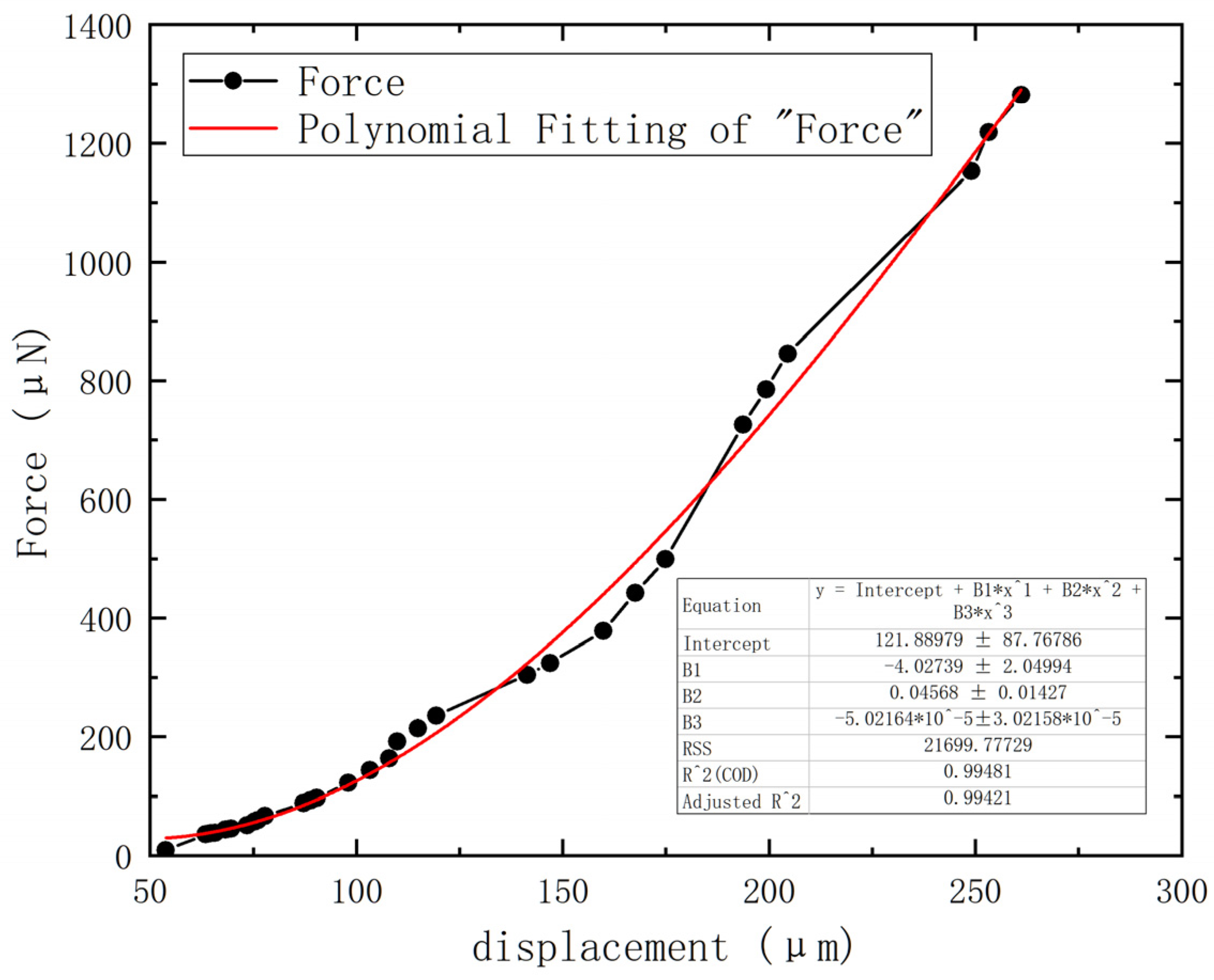

3.2. Calibration of Thrust Test Bench

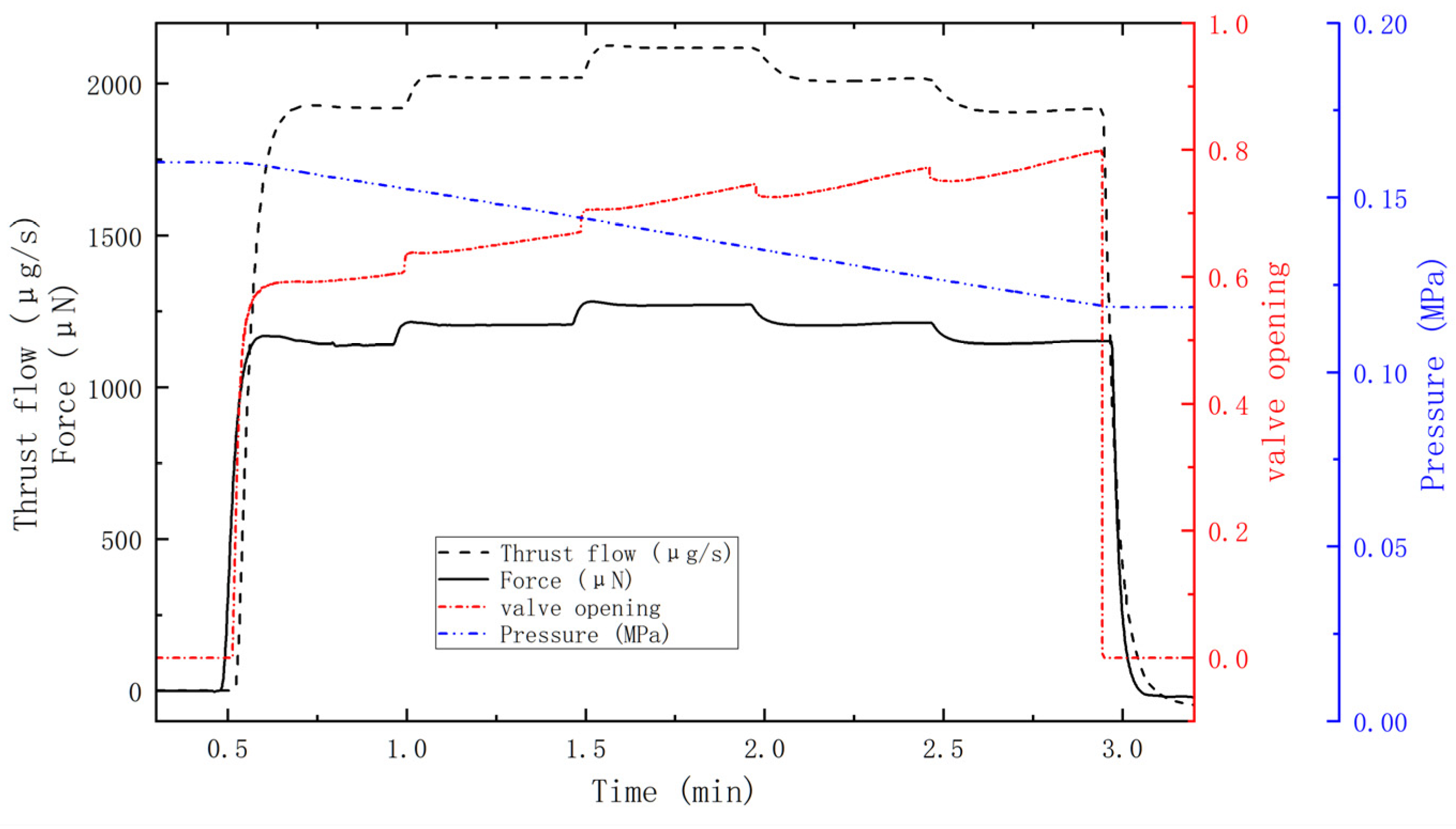

4. Results and Discussion

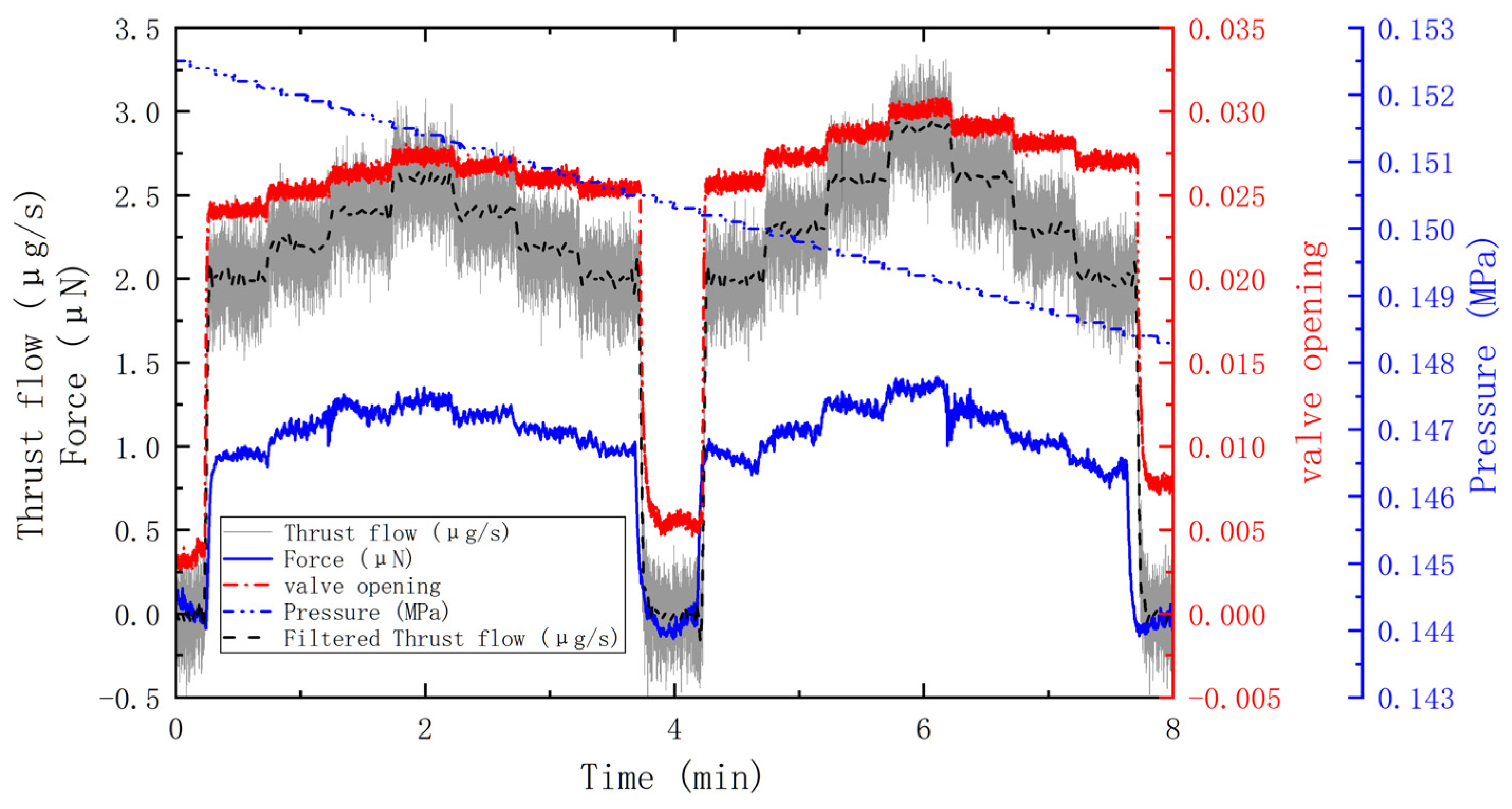

4.1. Thrust Range

4.2. Thrust Resolution

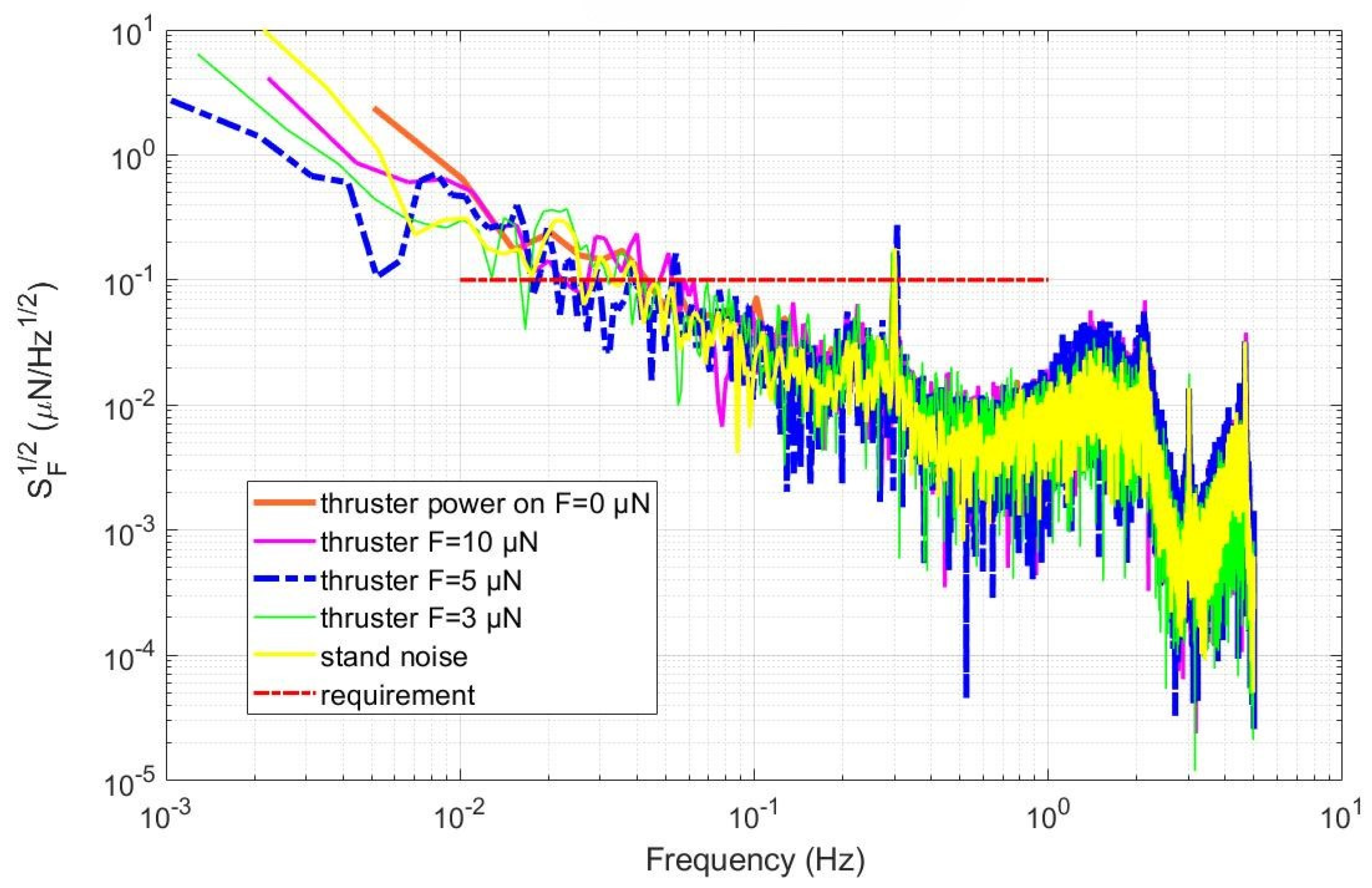

4.3. Thrust Noise

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marie, J.; Cordero, F.; Milligan, D.; Ecale, E.; Tatry, P. In-orbit experience of the Gaia and LISA Pathfinder cold gas micro-propulsion systems. In Space Operations: Inspiring Humankind’s Future; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 551–574. [Google Scholar]

- Lienart, T. First in-flight observations of the Cold Gas Propulsion System for CNES’Microscope spacecraft. In Proceedings of the 53rd AIAA/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–12 July 2017; p. 4947. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchetta, A.; Saponara, M.; Torasso, A.; Criado, G.S.; Girouart, B. The Euclid AOCS science mode design. CEAS Space J. 2015, 7, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Bai, Y.; Cai, L.; Cao, B.; Chen, W.-M.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, D.-C.; Ding, Y.-W.; Duan, H.-Z.; Gou, X.; et al. The first round result from the TianQin-1 satellite. Class. Quantum Gravity 2020, 37, 185013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wu, Y. The Taiji Program in Space for gravitational wave physics and the nature of Gravity. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2017, 4, 685–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, A.; Ziegler, T.; Schubert, R.; Brandt, N.; Bergner, P.; Johann, U.; Fichter, W.; Grzymisch, J. In-orbit performance of the LISA Pathfinder drag-free and attitude control system. CEAS Space J. 2018, 10, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Bejhed, J.; Kratz, H.; Bruhn, F.; Lindberg, U.; Hjort, K.; Stenmark, L. A hybrid cold gas micro thruster system for spacecraft. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2002, 97, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.; Chou, S.K.; Riaz, F.; Karthikeyan, K. Cold gas micro propulsion development for satellite application. Energy Procedia 2017, 143, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktor, P.; Jafry, Y.; DeBra, D. On orbit thruster calibration with applications to Gravity Probe B. In Automatic Control in Aerospace 1992, Proceedings of the 12th IFAC Symposium, Ottobrunn, Germany, 7–11 September 1992; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 525–530. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt, C.; Muhlfelder, B.; DeBra, D.; Parkinson, B.W.; Turneaure, J.P.; Silbergleit, A.S.; Acworth, E.B.; Adams, M.; Adler, R.; Bencze, W.J.; et al. The Gravity Probe B test of general relativity. Class. Quantum Gravity 2015, 32, 224001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBra, D.; Bencze, W.; Everitt, C.; VandenBeukel, J.; Kirschenbaum, J. Proportional helium thrusters for Gravity Probe B. Class. Quantum Gravity 2015, 32, 224016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matticari, G.; Noci, G.; Siciliano, P.; Colangelo, G.; Schmidt, R. Cold gas micro propulsion prototype for very fine spacecraft attitude/position control. In Proceedings of the 42nd AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Sacramento, CA, USA, 9–12 July 2006; p. 4872. [Google Scholar]

- Sarritzu, A.; Pasini, A. Performance comparison of green propulsion systems for future Orbital Transfer Vehicles. Acta Astronaut. 2024, 217, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Chen, L.; Duan, H.; Gong, Y.-G.; Hu, S.; Ji, J.; Liu, Q.; Mei, J.; Milyukov, V.; Sazhin, M.; et al. TianQin: A space-borne gravitational wave detector. Class. Quantum Gravity 2016, 33, 035010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milyukov, V. TianQin space-based gravitational wave detector: Key technologies and current state of implementation. Astron. Rep. 2020, 64, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Yan, H.; Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Geng, J.; Chen, T.; Fu, T.; Su, G.; Hu, Y.; Han, D. The view of micropropulsion technology for China’s advanced small platforms in deep space. Space Sci. Technol. 2022, 2022, 9769713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, W.; Xu, H.; Li, Q.; Li, Z.; Yang, S.Q.; Liu, J.P. Micronewton Cold Gas Thruster Based on Silicon-Etched Two-Dimensional Nozzles. AIAA J. 2024, 62, 3418–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packan, D.; Jarrige, J.; Thobois, P.; Blanchard, C.; Elias, P.Q.; Fallerini, L.; Noci, G. Micronewton balance measurements at Onera and application to the GAIA Mission. IEPC Pap. 2013, 418, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrige, J.; Thobois, P.; Blanchard, C.; Elias, P.-Q.; Packan, D.; Fallerini, L.; Noci, G. Thrust measurements of the Gaia mission flight-model cold gas thrusters. J. Propuls. Power 2014, 30, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guan, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Li, F.; Yu, X. Dynamic-force extraction for micro-propulsion testing: Theory and experimental validation. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2018, 89, 115110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Gao, Y.; Mao, Q.; Ye, L.-W.; Hu, Z.-K.; Zhang, K.; Song, P.; Li, Q. A compound pendulum for thrust measurement of micro-Newton thruster. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2022, 93, 064501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Mao, Q.; Gao, Y.; Wei, L.; Ding, Y.; Tu, H.; Song, P.; Hu, Z.; Li, Q. A newly designed decoupling method for micro-Newton thrust measurement. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2023, 94, 014504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, J.; Tu, L.; Yang, S.; et al. Ground-vibration suppression by a matched center of mass for microthrust testing in spaceborne gravitational-wave detection. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2023, 19, 024040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.; Sun, H.; Liu, K.; Cui, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Jiao, X.; Dong, Q.; Liu, L. Investigating the repeatability error in thrust measurement on a pendulum-based stand. Measurement 2024, 238, 115397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.; Cui, Q.; Sun, H.; Liu, K.; Liu, L. An integrated weak thrust stand based on vertical pendulum and its performance characteristics. Chin. Space Sci. Technol. 2024, 44, 154–163. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hernando, J.; Sánchez-Rojas, J.; Schmid, U.; Ababneh, A.; Marchand, G.; Seidel, H. Characterization and displacement control of low surface-stress AlN-based piezoelectric micro-resonators. Microsyst. Technol. 2010, 16, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchilloux, P.; Le, L.; Lhermet, N.; Patient, G.; Claeyssen, F.; Lang, M. Application of amplified piezoelectric actuators to the construction of gas valves. In Proceedings of the Smart Structures and Materials 2003: Industrial and Commercial Applications of Smart Structures Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA, 4–6 March 2003; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2003; Volume 5054, pp. 309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Motoo, K.; Toda, N.; Arai, F.; Fukuda, T.; Matsuno, T.; Kikuta, K.; Hirano, S.-I. Tailor-made multilayer piezoelectric actuator having large displacements and forces. Nippon Kikai Gakkai Ronbunshu C Hen/Trans. Jpn. Soc. Mech. Eng. Part C 2006, 72, 3302–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Cross, L. Piezoelectric tubes and tubular composites for actuator and sensor applications. J. Mater. Sci. 1993, 28, 3962–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, E.; Ananthasayanam, B. Piezoelectric actuation of a compliant semi-infinite beam. In Proceedings of the Smart Structures and Materials 2004: Modeling, Signal Processing, and Control, San Diego, CA, USA, 14–18 March 2004; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5383, pp. 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Duan, B.; Wu, L.; Hua, Z.; Bao, Z.; Guo, N.; Ye, Y.; DeLuca, L.T.; Shen, R. Development of a steady-state microthrust measurement stand for microspacecrafts. Measurement 2021, 178, 109357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Wu, H.; Tang, H.; Liu, Y.; Liang, X. Development and testing of a new thrust stand for micro-thrust measurement in vacuum conditions. Vacuum 2013, 91, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Li, X. A novel design method for the micro-thrust measurement system. Measurement 2023, 221, 113543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, D.; Li, H. Development of a cantilever beam thrust stand for electric propulsion thrusters. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2020, 91, 115104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, S.; Gao, Y.; Tu, H.; Wang, X.; Fu, X.; Meng, G.; Long, J.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. Thrust Measurement of an Integrated Multi-Sensor Micro-Newton Cold Gas Thruster. Aerospace 2025, 12, 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12030210

Lu S, Gao Y, Tu H, Wang X, Fu X, Meng G, Long J, Liu X, Li Y. Thrust Measurement of an Integrated Multi-Sensor Micro-Newton Cold Gas Thruster. Aerospace. 2025; 12(3):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12030210

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Songcai, Yong Gao, Haibo Tu, Xudong Wang, Xinju Fu, Gang Meng, Jun Long, Xuhui Liu, and Yong Li. 2025. "Thrust Measurement of an Integrated Multi-Sensor Micro-Newton Cold Gas Thruster" Aerospace 12, no. 3: 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12030210

APA StyleLu, S., Gao, Y., Tu, H., Wang, X., Fu, X., Meng, G., Long, J., Liu, X., & Li, Y. (2025). Thrust Measurement of an Integrated Multi-Sensor Micro-Newton Cold Gas Thruster. Aerospace, 12(3), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12030210