Winging It: Key Issues and Perceptions around Regulation and Practice of Aircraft Maintenance in Australian General Aviation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Aims and Objectives

- What perceived changes in regulation and/or in the role of the regulator have impacted the GA sector in Australia, and to what extent are these changes perceived to have diminished safe operations?

- What specific practical and operational challenges does the GA industry have to deal with to sustain safe operations going forward?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Changes to Industry and Working Practices

I think they should learn an air law before they come out on the shop floor for their apprenticeship. In that way, that’s just ridiculous to not have air law knowledge before you actually go and work in the industry. It’s not a part of the setup which should be.(P_9)

[Trainees today] never really learn and they never become accountable for actually [becoming competent]. Since they know that there is—“hang on a minute, if I just cock this up and I don’t put any effort in, but I keep turning up, I’m going to get through anyway”.(P_10)

I did one year full-time of the Cert IV. That got me, basically, two-thirds of my theory out of the way. During that time, I was doing work experience with four different operators.(P_2)

Younger people coming through with these training organizations need to be trained practically on the job, and they just need the input from the older people.(P_8)

[Apprentices are] coming out very insecure and very poorly trained, I suppose, because they just haven’t had that time being mentored by the good engineers […] there’s just not that same level of mentorship, I feel, anymore.(P_2)

A lot of employers these days don’t have the money or the time to baby in a practice. They want them to come in as a second-year apprentice, basically. They are new one year, come in as a second year, and be able to let them go into the work. You can’t do that. That happens on a daily basis. That is just how it happens. That’s why I don’t have apprentices anymore and I will not, I will not, I don’t have the time.(P_5)

AndPeople in General Aviation either can’t afford [to maintain their aircraft] or don’t want to pay. They will shop around and find the cheapest place, which means that there are unscrupulous organizations out there that will cut corners, that will do it cheaper;(P_4)

I’ve seen airplanes go into a hangar and then an hour later, they roll out and the annual inspection has been done on them. You can’t do that in GA. There are some shops around that do it, but they tend to get found out. The industry, as you said before, is quite a small industry. There’s enough scuttlebutt around that you hear, that you don’t take your pioneer. They’re dodgy. Or, if you want a hundred hourly done, fly over the airfield and it’ll turn up in the mail a week later;(P_10)

“[You fix faults] in accordance with the maintenance manual and that’s it […] [The new Maintenance Engineer’s] idea of fault finding is, ‘oh that’s loose, or there’s the fault.’ Fix it by replacement instead of repair quite often.(P_3)

[The regulators are] bogging down the engineer with paperwork and not letting the engineer do what engineers do best, which is work on aircraft, or supervise people that are working on aircraft.(P_4)

AndWe’re doing a job at the moment where we’re being told to leave things to another year to reduce the cost and then spread it across. More people saying, “Oh, we’re going to be changing that in a year and a half. Can you just sign it off?”;(P_9)

Some owners simply don’t have the funds to be able to sustainably maintain their aircraft in an airworthiness state […] the LAME has to be the one, I suppose, who makes the decision to go, “I’m just not going to sign this airplane out again until we do $30,000 worth of work”;(P_2)

You may be put under a position where it’s Friday night and an owner is screaming, to go away kids and family. You go, “Bring it in. We’ll do an oil change. I had a good look at it this last time.” You know the member. You know the aircraft. You’re intimate with it. Maybe you won’t do every checklist in there, because last time, you did the whole thing. You sign it off, and you might, six weeks later, have a disgruntled person that leaves there. They then ring the regulator and go, “He didn’t do this proper annual”.(P_10)

There is no right of reproach. You cannot go to anyone within [the regulator] and argue it. Recently I did my [aircraft] exam for my license […] Doing the exam, I noticed there were some discrepancies in the wording […] When I rang [the regulator], they effectively said “stick your head up your ass, we don’t care, we are the regulator and we will do what we want to do.” They are not engaging with it.(P_10)

[The regulator is] trying to help more than they have done, and it is happening. Some of the things I’ve learned over the past and put into the company like doing safety meetings, things like that … Yeah, that’s all stuff that we never used to do in the past, but it’s a positive;(P_9)

The small operators are being pushed out now. There’s an argument that those smaller dodgy operators get filtered out of the industry. Perhaps that’s one of the goals of this increased compliance;(P_2)

And[The Regulator] has devolved responsibility in a number of different areas, some good, some bad;(P_4)

[The Regulator] bought out a SID’s program, which is causing a few dramas and ripples around the industry but in some ways, is actually a good thing because we’re finding… like we recently found some tail plane cracks on a Cessna because of…we would have found them anyway, but it was a part of the SID’s program;(P_9)

3.2. Role of the Regulator

…we get audited constantly, and you know just picking up little things like where it tool—we used a tool tag system for tool control, one of the numbers was a bit worn off on a tool tag, it then becomes an audit finding […] at the end of the day that bit of paint worn off a tool tag is not going to make an aircraft come down […]I’ve never seen an audit come through with a clean slate.(P_1)

Paper work’s always good. You have to have it but, jeez, it’s gotten ridiculous now. Back in the day, you’d change a light bulb and go to the pilot, “Yep, you’re good to go.” I change a light bulb and now, is still takes me ten minutes to change it, but it is an hour of paperwork.(P_5)

The regulatory body is less concerned about the quality of the work that the engineers are doing and more concerned about the paperwork that they’re producing.(P_4)

…recently, we had three airworthiness inspectors [from the regulator] turn out at a local airfield. They spent three days going over a flying school. They called up the LAME, and they were standing there with a fistful of papers saying, “Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. You’ve done wrong. You’ve done wrong.” The [LAME] turned around and said, “Well, actually no, what you’re citing as a reference isn’t applicable, because that’s for an airline. These aircraft are a lesser weight”.(P_10)

It’s a lack of education. It’s like when I registered the aircraft in my name, or put my name down as a registered operator, did I get a leaflet from [the regulator] saying, “as the registered operator you are required to bang, bang, bang?” I think there’s a misunderstanding in the industry, particularly in the private aircraft sector of who holds responsibility and what those people are required to do […] It’s law you should know it. I personally think there should be some onus on CASA too, you’re the registered operator of this aircraft.(P_4)

I have a lot of concerns, not only about the engine. I have a lot of concerns about, first of all, the certification of the aircraft, I have a lot of concerns about the engineering of the aircraft, the standards of the engineers. How they check the engineering standards, there was no oversight happening from [the regulator] at all.(P_4)

[The regulator] impacts the industry because [maintenance engineers] will then do things that they shouldn’t do. They know [what to do] they’ve done it that way for years. They know that it isn’t a safety case, it’s more a compliance issue, but they just do it because they’ve done it that way for years. Then, the regulator comes in and smacks them down, so then they don’t do it. That increases the cost. It increases the time. People don’t want to own aircraft. They sell aircraft, so we see these gradually diminishing infrastructure and system that shouldn’t need to be that way […] we have a regulator who sees it’s better to regulate than to educate and to assist.(P_10)

It’s this regulatory oversight that’s happening on everything all the time. Every time I pick up the phone and talk to [the regulator] they want to send a bill, so the government funded safety authority, that is also funded out of the levy that is put on fuel. Yet every time I do something, they want to charge me for it. I’m not sure how all of that works, are they double dipping? Are they now a profit center for the government? Yet they [are] supposed to be the safety authority […] at the moment it’s as the authority and the regulator aren’t telling you “you need to do this”, [they are saying that] to do that you need to come to us and when you come to us we’re going to charge you.(P_4)

I’ve worked on the spinners with guys that were too lazy to do their LAME license. They were more than happy for me to sign for their work. Those people are now [working in the regulator office], in regulatory roles, enforcing rules that they really don’t have the privilege to [enforce].(P_10)

3.3. (Re)calibration of Underlying Values and Philosophies

Fault finding is what I love doing. I like having a customer come in and say I have a problem with this, and I go search the memory bank and you try and find a solution to it. That, to me, is the best part […] I enjoy being the chief engineer because I can make the decisions.(P_8)

Engineers are either passionate and believe in what they’re doing and want to do it the right way […] or they’re tainted by the industry, they have no respect for the industry, they have no respect for what the industry is trying to achieve. Consequently, they’d rather spend more time on their telephone organizing the building of their new house, while they’re charging the client.(P_4)

I’ve never come across such a toxic, mind state as aviation. Everyone’s an expert. The only people they should listen to LAMES because they’ve earned their right, but anyone feels that, well, hey, I can work on a mower, I can work on an airplane. Why would I need to pay you 120 dollars, 150 dollars an hour to do something I can do myself? Then they will use commercial-grade hardware. We refer to it as “Bunnings Aerospace”;(P_10)

You, effectively, really only start to learn when you become licensed. From that day, when you’re accountable for you own action is when you actually start really learning.(P_10)

I’ve worked with some engineers that I’ve basically said, “I don’t want those engineers working on my aircraft again […] I can see what they’re doing, I don’t like what they’re doing, I don’t like their attitude”;(P_4)

And[Trainees] have all sorts of funny preconceived ideas about what their first job’s going to look like and how the industry actually is or is not ;(P_2)

The guys that come in for work experience, they’ve already done their one-year course and they don’t want to be there. They already believe that they know more than you.(P_5)

[Trainees] have done their year course, they’ve paid all the money, they’re ready to work on planes—and they’re not;(P_5)

andI believe that there is no respect anymore. Kids these days, we see them coming through industry. They want to sit there with their thumbs on their phone […] There is certainly a lack of accountability amongst younger people these days. They want everything for nothing. They don’t want any hard work to do it;(P_10)

You can’t put full trust in somebody straightaway as they walk in the door, but you need to trust that they can use a screwdriver or spanner properly and things like that. They don’t seem to have that sort of thing when they come into the shop as an apprentice.(P_9)

3.4. Work as Imagined vs. Work as Done

People coming from the college were a bit off with experience, and they’ve been working on an engine or aircraft that’s in their facility, that’s been pulled apart last month and put back together, whereas they come here and it’s a plane that hasn’t been pulled apart for ten years and everything’s rusted and corroded;(P_7)

Everyone that I’ve come across has come out without any knowledge of what we’re actually doing on the floor;(P_8)

AndWhen you get trained it’s always this perfect picture, and then the real life. It’s not so perfect. Definitely certain places have different methods to other places. Some I agree with, some I don’t;(P_6)

Because [the exam is] written by bureaucrats, there’s no real relevance to what you actually do in the field to what you learn in the exam.(P_10)

[Work experience] giving the apprentices the appreciation as to what it is actually like in the working environment, I think there’s a lot of benefit in that. Yeah and in my case, it led into an apprenticeship at the end of it. I highly recommend that apprentices and people in the airline industry do that.(P_2)

I think, go back many years it was all on the job training, and so the bad habits that an engineer taught to another engineer, taught to another engineer, taught to another. Just got passed down and then got even made worse to the point where you have an apprentice who’s being taught by someone whose got a license, yet the work’s crap.(P_4)

You read the maintenance manual and it just says, “Fix it.” There’s no interpretation, you know? […] Quite often the manual will give you all of the information you need to know on how to build it from the nut up, but you’re not doing that. You need to dive into that particular part that you’re involved with, you know? Then use the manual to repair it from there, not from go to whoa. Understanding the manual and interpreting it is a real challenge.(P_3)

…having this mindset that the regulator tells you that you are not to refer to anything mentally. You are to refer to a manual to do any servicing and maintenance.(P_10)

3.5. Practical and Operational Challenges for GA

[In] Australia, unfortunately, you haven’t really learnt from the mistakes made in the UK, so they’re trying to make the General Aviation industry the same as the [commercial] airline industry, which doesn’t work […] [they] are very different ballgames.(P_9)

And“One of the problems is we do a lot of the maintenance on vintage aircraft, and some of the parts just, you can’t get a new part with a release note and then there’s perfectly good serviceable parts that are available from the parts bin. You’re not allowed to use it theoretically;(P_7)

The levels that [the regulator] are wanting people to come up to, and the standards that they’re wanting us to comply with, are good. But they need to be careful, though, particularly with small operators, that the effort and the cost and the time required with compliance doesn’t detract from actually getting the job done properly and getting the job done safely. It can start to be counterproductive, particularly in small organizations where resources are having to be divided to the compliance side of thing.(P_2)

The most difficult point is when [your company] grows to the size that you can’t afford the overhead of having someone like a business manager, but you can’t afford not to because you physically can’t do it and it’s not your forte;(P_4)

How do we still make profit trying to do all this paperwork, trying to help apprentices? It goes back to that again—you don’t get time;(P_5)

And[The implication of the regulator’s] high standards that they’re trying to promote throughout the industry is there’s a real … Small operators are real disadvantaged […] It’s basically only able to be done sustainably with bigger organizations. Middle level and larger organizations seem to be the only organizations that can continue to be able to be sustainable;(P_2)

Most of the maintenance goes abroad these days for the heavy stuff. To the lower maintenance, you still have 2 or 3 engineers that are available to work on their airplanes, where in General Aviation, we generally have maybe 1 to 2 for the entire airplane. We have 25 multiple jobs happening at (any) one time.(P_9)

[Aircraft owners] simply just can’t afford to repair their aircraft, so there’s compromises need to be made in terms of, “Okay, we’ll do these jobs this time. We’ll stretch these other jobs out for another hundred hours for the next inspection,” or what have you.(P_2)

AndWe’re entering a very interesting time in the aviation industry, particularly in GA, where the best competent engineers are in the office, off the tools, and the least competent engineers are operating hands-on on the aircraft;(P_2)

Those that are trying to do it the right way can’t afford to stay in business, so they fall out of business. Which means that all you end up with is are those that have cut the corners and you now have an unsafe engineer environment in General Aviation. End of story.(P_4)

Back in my day, you were taught, you were given a competency, when you expressed that you knew what you were doing, you were examined and tested on that. You were then given that privilege. If you didn’t know and you made a mistake, you got a thick ear. You were off your machine, you were out sweeping floors. There was a consequence for you not putting that effort in. These days, there’s no consequence.(P_10)

AndIf I could know half of what [my Dad] knows [about aviation maintenance engineering] I’d be doing well, you know? I think there’s still a bit of a concern now that there’s not that much experience coming out of the schools and apprentices and stuff ;(P_3)

The sad thing is that the guys at my age are becoming less and less, and those young people aren’t getting the experience from them.(P_8)

There’s not many apprentices coming through […] I just loved working with older [engineers] because they could give me hints and guidance on where to go and what to do. I’m, me now as being one of those older people, don’t have the opportunity to teach the young.(P_8)

The apprentices are just having to learn by trial and error and on their own. They’re coming out very insecure and very poorly trained […] As bigger companies try and keep costs down, those budgets that training apprentices, they don’t have those budgets for extra people on the floor to mentor and to guide and to hand over those skills to the apprentices.(P_2)

Small operators are real disadvantaged. The days of having a small operator, be it a charter company or be it a maintenance organization with just the chief engineer, the owner, and a couple of LAMEs … Those days are gone because you need so many senior persons now just to be able to meet requirements;(P_2)

AndThe main thing for me is money. That’s the biggest negative at the moment is that you’re always fighting it […] For some reason, the General Aviation industry, people think that everyone should … We should be a bank for them. […] It’s like, “well, we’re a small business, we can’t afford to do that.” In the same respect, it’s … Then [maintenance engineers] have problems paying our people and our suppliers and, by law, we’re supposed to be able to afford to operate;(P_9)

The cost of parts have gone up because of the new system. The cost of maintenance has gone up because of the new system. Owners can’t afford planes these days and when they do, they can only just afford them. However, they still want the plane maintained perfectly and they still have to have their plane yesterday.(P_5)

Back when it was [the aircraft] only 10 years old, yeah, $150 is fine because it didn’t need all this major work. Now, you need to be putting money aside for not just your mandatory component overhauls, but major refurbishment: air frame and avionics upgrades, paint interiors, things that have never been replaced in the aircraft’s life;(P_2)

AndWe haven’t made profit in two years. It’s not possible to make a profit, but the customers still complain about the bill;(P_5)

The hardship now, really, is that there’s a lack of money in the industry, not only, from an engineering perspective, but from the customer’s perspective. Everyone’s trying to scrimp and save.(P_9)

3.6. General Discussion

3.6.1. Changes and Impacts in Regulation and to the Regulator Role to the GA sector

3.6.2. Practical and Operational Challenges in the GA Industry

3.6.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

3.6.4. Implications and Future Research Directions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO). Annex 6 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, Operation of Aircraft, Part I—International Commercial Air Transport–Aeroplanes, 11th ed.; International Civil Aviation Organisation: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, S. Foundations of Safety Science: A Century of Understanding Accidents and Disasters; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- CASA. Sector Risk Profile for the Small Aeroplane Transport Sector. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/sites/default/files/srp_small_aero_booklet.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Boyd, D.D.; Stolzer, A. Accident-precipitating factors for crashes in turbine-powered general aviation aircraft. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 86, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.D. Causes and risk factors for fatal accidents in non-commercial twin engine piston general aviation aircraft. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 77, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASA. Safety Behaviours, Human Factors: Resource Guide for Engineers. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/sites/default/files/_assets/main/lib100215/hf-engineers-res.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- ATSB. Aviation Occurance Statistics 2005 to 2014. Available online: https://www.atsb.gov.au/publications/2015/ar-2015-082/ (accessed on 23 January 2020).

- BITRE. General Aviation Study—[Statistical Report—978-1-925531-77-0]. Available online: https://www.bitre.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-11/cr_001_0.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Haynes. The Theory and Practice of Change Management; Palgrave: Hampshire, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- CASA. SMS for Aviation—A Practical Guide: Safety Assurance. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/safety-management/safety-management-systems/safety-management-system-resource-kit (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- CASA. Part 43—Maintenance of General Aviation and Aerial Work Aircraft (CD 1812SS). Available online: https://consultation.casa.gov.au/regulatory-program/cd1812ss/ (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Naweed, A.; Kingshott, K. Flying off the handle: Affective influences on decision making and action tendencies in real-world aircraft maintenance engineering scenarios. J. Cognit. Eng. Decis. Making 2019, 13, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingshott, K.; Naweed, A. “Taxiing down the runway with half a bolt hanging out the bottom”: Affective influences on decision making in general aviation maintenance engineers. In Proceedings of the 2018 Ergonomics & Human Factors Conference, Birmingham, UK, 23–25 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, D. The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture and Deviance at NASA; Uni of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Naweed, A.; Chapman, J.; Trigg, J. “Tell them what they want to hear and get back to work”: Insights into the utility of current occupational health assessments from the perspectives of train drivers. Transp. Res. Part. A 2018, 118, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naweed, A.; Dorrian, J.; Rose, J. Evaluation of Rail Technology: A Practical Human Factors Guide; CRC Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Naweed, A.; Balakrishnan, G.; Bearman, C.; Dorrian, J.; Dawson, D. Scaling Generative Scaffolds Towards Train Driving Expertise, in Contemporary Ergonomics and Human Factors 2012: Proceedings of the International Conference on Ergonomics & Human Factors 2012; Anderson, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Blackpool, UK, 2012; p. 235. [Google Scholar]

- Naweed, A. Psychological factors for driver distraction and inattention in the Australian and New Zealand rail industry. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 60, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, G.; Calderwood, R.; Macgregor, D.G. Critical decision method for eliciting knowledge. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern. 1989, 19, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, A.; Howard, S. Methods & tools: The rich picture: A tool for reasoning about work context. Interactions 1998, 5, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Checkland, P. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Naweed, A. Getting mixed signals: Connotations of teamwork as performance shaping factors in network controller and rail driver relationship dynamics. Appl. Ergon. 2020, 82, 102976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naweed, A.; Rainbird, S.; Chapman, J. Investigating the formal countermeasures and informal strategies used to mitigate SPAD risk in train driving. Ergonomics 2015, 58, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabel, A.; Naweed, A.; Ferguson, S.A.; Reynolds, A. Crack a smile: The causes and consequences of emotional labour dysregulation in Australian reef tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 1598–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naweed, A.; Rose, J. “It’s a Frightful Scenario”: A Study of Tram Collisions on a Mixed-traffic Environment in an Australian Metropolitan Setting. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 2706–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naweed, A.; Ambrosetti, A. Mentoring in the rail context: The influence of training, style, and practice. J. Workplace Learn. 2015, 27, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hofstede, G.; Milosevic, D. Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASA. Cessna Supplemental Inspection Documents. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/aircraft/airworthiness/cessna-supplemental-inspection-documents (accessed on 2020 25 March).

- Dekker, S.W.A. The bureaucratization of safety. Saf. Sci. 2014, 70, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, E. The nitty-gritty of human factors. In Human Factors and Ergonomics in Practice: Improving System Performance and Human Well-Being in the Real World; Shorrock, S., Wiliams, C., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Naweed, A.; Young, M.S.; Aitken, J. Caught between a rail and a hard place: A two-country meta-analysis of factors that impact Track Worker safety in Lookout-related rail incidents. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 2019, 20, 731–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Chong, E. Power distance in Singapore construction organizations: Implications for project managers. Int. J. Project Manag. 2003, 21, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.S.; Carter, M.Z.; Zhang, Z. Leader–team congruence in power distance values and team effectiveness: The mediating role of procedural justice climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieck, A.M. Exploring the nature of power distance on general practitioner and community pharmacist relations in a chronic disease management context. J. Interprofessional Care 2014, 28, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naweed, A.; Dennis, D.; Krynski, B.; Crea, T.; Knott, C. Delivering simulation activities safely: What if we hurt ourselves? Simul. Healthc. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, N. A new accident model for engineering safer systems. Saf. Sci. 2004, 42, 237–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Read, G.J.; Naweed, A.; Salmon, P. Complexity on the rails: A systems-based approach to understanding safety management in rail transport. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 188, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.M.; Read, G.J.; Walker, G.H.; Goode, N.; Grant, E.; Dallat, C.; Carden, T.; Naweed, A.; Stanton, N.A. STAMP goes EAST: Integrating systems ergonomics methods for the analysis of railway level crossing safety management. Saf. Sci. 2018, 110, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Voogt, A.; Chaves, F.; Harden, E.; Silvestre, M.; Gamboa, P. Ultralight Accidents in the US, UK, and Portugal. Safety 2018, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Topic | Example Content | Example Questions |

|---|---|---|

| General experience in aviation | Background, entry into industry, rapport building questions | “What is your background in aviation?” “Do you remember the first aircraft you fixed?” |

| Current processes and changes in the industry | Training delivery, industry status past and present, challenges | “How has the aviation industry changed over the years?” “What aspects of the industry do you find most challenging?” |

| Safety in aviation maintenance | Changes in safety, positive and negative influences | “How has the safety of aviation maintenance changed over the life of your work?” “What has a negative impact on safety?” |

| Factors impacting a maintenance task | Distractions, pressures in day-to-day maintenance work | “What pressures do you feel when completing a job?” “How do you limit distraction during work?” |

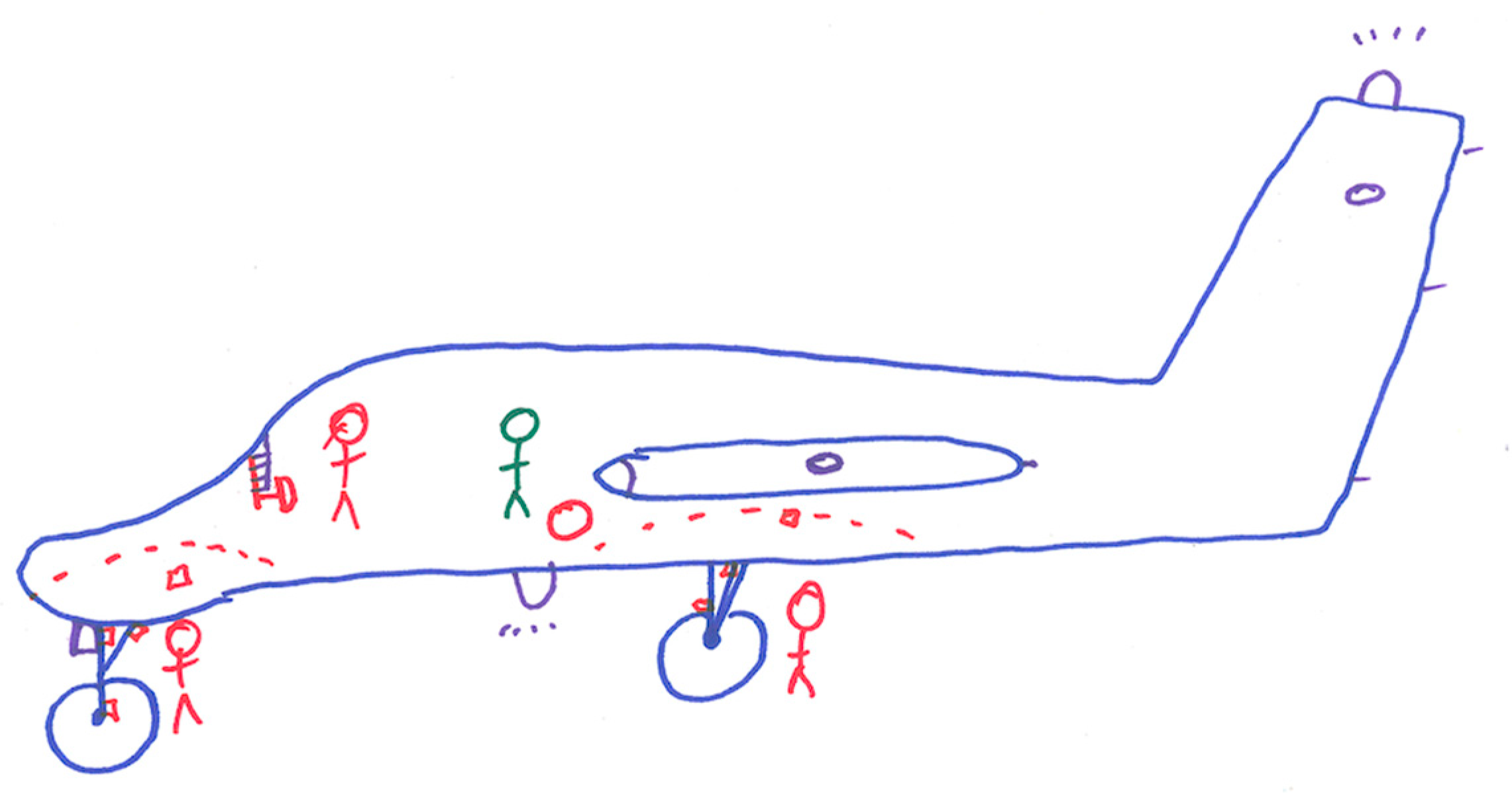

| Scenario Invention Task Technique Activity | Create scenario | “Imagine you are at work and completing a difficult maintenance engineering task. Use the pen-paper to describe this task, using any drawing convention you wish.” |

| Recall and retell | “What else would be going on around you?” |

| Themes | Major Categories | N1 | Frequency of Statements | Theme Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changes to Industry and Working Practices | General decline in training and education | 7 | 16 (10%) | 47 (29%) |

| Drift in working practices | 6 | 12 (7%) | ||

| Emphasis and growth of safety culture | 5 | 11 (7%) | ||

| Wider power-distance gap | 3 | 8 (5%) | ||

| Role of the Regulator | Auditing and bureaucratization | 5 | 10 (6%) | 29 (18%) |

| Lack of clarity and support | 3 | 7 (4%) | ||

| Negative safety climate | 2 | 12 (7%) | ||

| (Re)calibration of Underlying Values and Philosophies | Working to live, not living to work | 6 | 15 (9%) | 27 (16%) |

| Attitudinal stability | 5 | 12 (7%) | ||

| Work as Imagined vs. Work as Done | Theory vs. practical experience | 7 | 10 (6%) | 16 (10%) |

| Restrictive maintenance manuals | 3 | 6 (4%) | ||

| Practical and Operational Challenges for GA | Mismatch between GA and commercial aviation sector | 6 | 13 (8% | 45 (27%) |

| Safety-risk and safety concerns | 5 | 11 (7%) | ||

| Workforce development | 4 | 10 (6%) | ||

| Financial burden | 4 | 11 (7%) |

| Theme | Major Categories | Minor Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Changes to Industry and Working Practices | General decline in quality of training and education | Training changed for worse |

| Mentoring | ||

| Regulator knowledge | ||

| Drift in working practices | Unscrupulous operators | |

| Aircraft owners | ||

| Maintenance work | ||

| Emphasis and growth of safety culture | ||

| Wider power-distance gap |

| Theme | Major Categories | Minor Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Role of the Regulator | Auditing and bureaucratization | Auditing excessive, rigged and undermining safety |

| Excessive bureaucracy | ||

| Lack of clarity and support | ||

| Negative safety climate | Regulation turned into a profiteering exercise | |

| Negation of responsibility | ||

| No confidence |

| Theme | Major Categories | Minor Categories |

|---|---|---|

| (Re)calibration of Underlying Values and Philosophies | Working to live, not living to work | Engineers are now Business Managers |

| GA requires passion | ||

| Attitudinal stability | Licensing culture | |

| Teamworking | ||

| Trainees and their sense of entitlement |

| Theme | Major Categories | Minor Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Work as Imagined vs. Work as Done | Theory vs. practical experience | Relevance of classroom to real-world setting |

| Work experience | ||

| Restrictive maintenance manuals | Inflexible | |

| Require interpretation |

| Theme | Major Categories | Minor Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Practical and Operational Challenges for GA | Mismatch between GA and commercial aviation sector | Regulation and compliance have poor fit with GA needs |

| Implications for sustainability | ||

| Safety-risk and safety concerns | From over-modulation of safety | |

| From loss of skills | ||

| Workforce development | Loss of knowledge and skills | |

| Staff turnover | ||

| Mentorship | ||

| Financial burden | Safety improvement increasing cost | |

| Age and cost of aircraft |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Naweed, A.; Kourousis, K.I. Winging It: Key Issues and Perceptions around Regulation and Practice of Aircraft Maintenance in Australian General Aviation. Aerospace 2020, 7, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace7060084

Naweed A, Kourousis KI. Winging It: Key Issues and Perceptions around Regulation and Practice of Aircraft Maintenance in Australian General Aviation. Aerospace. 2020; 7(6):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace7060084

Chicago/Turabian StyleNaweed, Anjum, and Kyriakos I. Kourousis. 2020. "Winging It: Key Issues and Perceptions around Regulation and Practice of Aircraft Maintenance in Australian General Aviation" Aerospace 7, no. 6: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace7060084

APA StyleNaweed, A., & Kourousis, K. I. (2020). Winging It: Key Issues and Perceptions around Regulation and Practice of Aircraft Maintenance in Australian General Aviation. Aerospace, 7(6), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace7060084