Learning from Incidents: A Qualitative Study in the Continuing Airworthiness Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Systematic Literature Review

- Subject—Related to learning from incidents and past experiences.

- Setting—Any high reliability industry or sector where learning from incidents is critical.

- Publication—Journal or peer-reviewed conference proceedings.

- Date range—published post 1992. The year 1992 was the starting point for the screening process, since at the time of planning the research project, 25 years was considered to be a reasonable timespan to include material pertaining to learning from incidents.

- Deductive—themes reported on are predetermined to some extent. In this case, these predetermined themes were the output of a focus group process.

- Inductive—themes reported are derived from analysis of the literature.

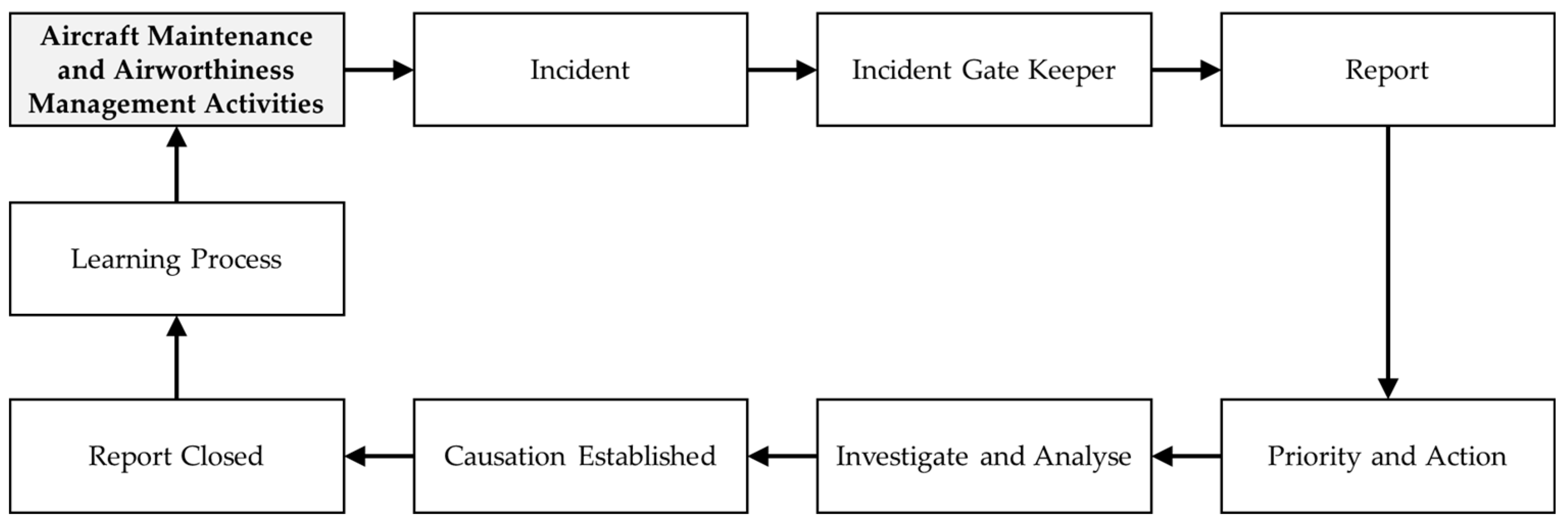

1.2. The Notion of a Generic Incident Lifecycle

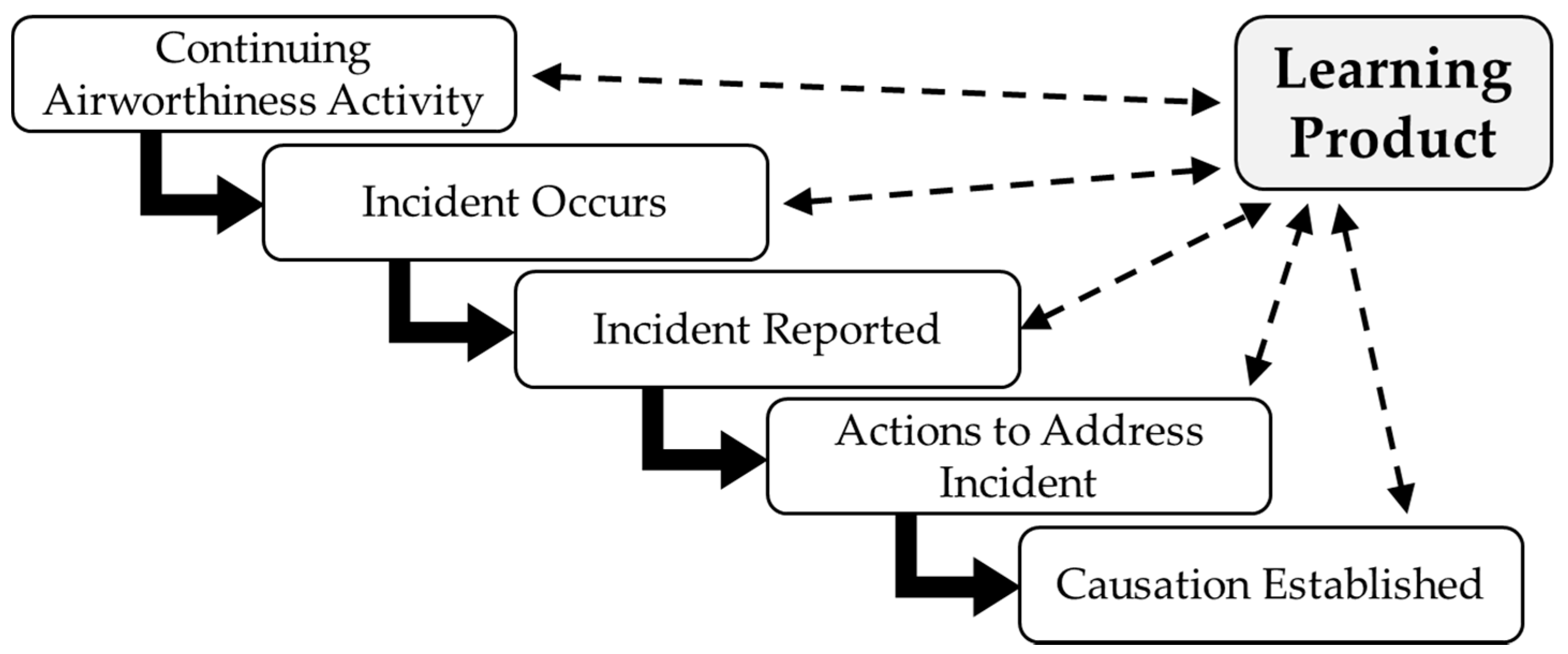

1.3. A Potential Learning Cycle Emerges

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Philosophical Underpinnings

2.2. Focus Group

2.3. Data Collection

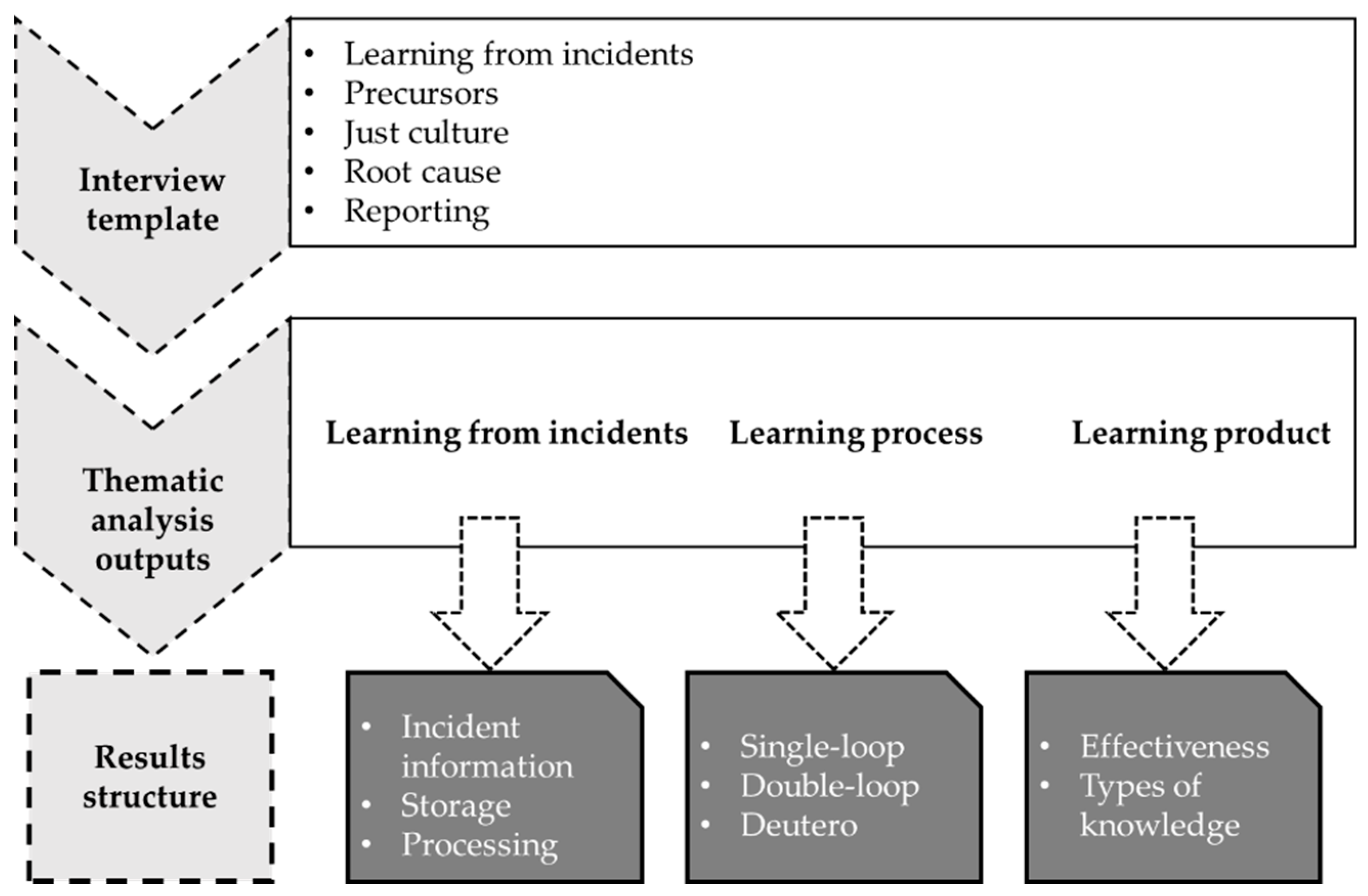

2.3.1. Instrument

2.3.2. Participants

2.4. Data Analysis

- The content of the cluster of codes which were being reported on.

- Patterns where relevant.

- Considering background information noted against participants and examining any patterns relating to participants’ profiles.

- Considering any relationship between codes and their importance in relation to the research questions.

- Noting any primary sources relating to the context of the relationship with the literature in addition to highlighting any gaps in the literature.

- Unit of analysis is an individual;

- Semi-structured interview guide was constructed following a systematic analysis of literature and the use of a focus group;

- Data were collected through qualitative interviews;

- Thirty-four interviews were collected in locations endorsed by eight organizations;

- Qualitative analysis based on the guidelines from Braun and Clarke [47] (thematic analysis) employing a six-phase approach was used in the study.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Framework

3.1.1. Learning form incidents—Acquiring, Processing and Storing Data

3.1.2. Learning Process—Single-Loop, Double-Loop and Deutero Learning

3.1.3. Learning Product—Effectiveness and Types of Knowledge

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview Template

| Code 1 | Code 2 | Previous Positions | Years in Previous Positions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position | Years in position | Qualification | Type of organization |

- Could you describe an occurrence/incident that happened recently?

- How is a report made?

- Who decides what events to report?

- Where does the requirement to report come from?

- How is the importance of reporting highlighted in the organization?

- What do you think the aim of reporting is?

- Have you received feedback from reports you have submitted?

- Do you think there is a good safety culture in the organization?

- Why is this?

- Is it easy to communicate with management on safety issues?

- Do you feel a just culture exists in the company? (Why is that?)

- How does just culture impact on reporting?

- How are lessons that arise from occurrence/incident reporting delivered to staff in your area?

- How is learning achieved? (What is the process?)

- What obstacles to learning from incidents have you experienced in your position?

- In your opinion, what conditions or developments could improve learning from incidents/occurrences in your organization?

- What is your opinion on efforts to establish a single root cause when an incident/occurrence is investigated?

- Is this approach always effective?

- What situations have you experienced where incident causes can be numerous and complex?

- How important is it to identify and report events not required by the mandatory occurrence reporting (MOR) schemes? (Why is this?)

- Is the organization’s occurrence/ incident reporting system capable of managing reports other than MOR’s?

- Is there a better way of gathering and using the potential information from non-mandatory events? (What would you suggest?)

Appendix B. Defining and Naming Themes

| Phase 5—Categories Conceptually Mapped and Collapsed into 3 Major Themes with 8 Sub-Themes | Code Definitions for Coding Consistency | Interviews Coded | Units of Meaning Coded |

|---|---|---|---|

| LEARNING PROCESS | This relates to the three levels of learning suggested by Bateson (1972) and applied by Argyris and Schon (1996) | 34 | 359 |

| Deutero-learning | This relates to when members of an organization reflect on previous learning and thereby setting about to improve its learning process. | 26 | 65 |

| Double-loop Learning | This relates to learning that takes place and organizational norms and theory in use are changed. | 26 | 63 |

| Single-loop Learning | This relates to when an organizations’ members detect and correct errors but still maintain the organizations theory in use. | 26 | 63 |

| LEARNING PRODUCT | This relates to what the learning process delivers | 33 | 235 |

| Effectiveness | This relates to measuring effectiveness of learning | 31 | 155 |

| Types of knowledge | This relates to conceptual, procedural, dispositional and locative knowledge | 23 | 74 |

| LEARNING FROM INCIDENTS | This relates to the inputs necessary to enable the assembly of a learning material in support of learning from incidents | 17 | 213 |

| Processing | This relates to how learning information is processed | 17 | 82 |

| Acquiring | This relates to the sources of information that support learning and how there are gathered | 16 | 55 |

| Storing | This relates to how learning information is stored | 12 | 27 |

References

- Drupsteen, L.; Hasle, P. Why do organizations not learn from incidents? Bottlenecks, causes and conditions for a failure to effectively learn. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 72, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.-H.; Wang, Y.-C. Significant human risk factors in aircraft maintenance technicians. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.A.; Carvalho, H.; Oliveira, M.J.; Fialho, T.; Soares, C.G.; Jacinto, C. Organizational practices for learning with work accidents throughout their information cycle. Saf. Sci. 2017, 99, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akselsson, R.; Jacobsson, A.; Bötjesson, M.; Ek, Å.; Enander, A. Efficient and effective learning for safety from incidents. Work 2012, 41, 3216–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, A.N. Human Errors in Context: A Study of Unsafe Acts in Aircraft Maintenance. Ph.D. Thesis, University of New South Wales, Kensington, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EU). Commission Regulation (EU) No 1321/2014 of 26 November 2014 on the Continuing Airworthiness of Aircraft and Aeronautical Products, Parts and Appliances, and on the Approval of Organisations and Personnel Involved in These Tasks; European Commission (EU): Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, C.; Stanton, N.A. Safety in system-of-systems: Ten key challenges. Saf. Sci. 2014, 70, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EU). Commission Regulation (EU) No 376/2014 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 3 April 2014 on the reporting, analysis and follow-up of occurrences in civil aviation, amending Regulation (EU) No 996/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council and repealing Directive 2003/42/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Regulations (EC) No 1321/2007 and (EC) No 1330/2007; European Commission (EU): Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gerede, E. A study of challenges to the success of the safety management system in aircraft maintenance organizations in Turkey. Saf. Sci. 2015, 73, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drupsteen, L.; Wybo, J.-L. Assessing propensity to learn from safety-related events. Saf. Sci. 2015, 71, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method, and Practice; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Drupsteen, L.; Guldenmund, F.W. What is learning? A review of the safety literature to define learning from incidents, accidents and disasters. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2014, 22, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, G.J.; Saunders, R.; Collyer, R. Developing a model to predict aircraft maintenance performance. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Aviation Psychology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 3–6 May 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sms, I. Safety Management Manual (SMM). In Doc 9859; ICAO: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, M.; McDonald, N.; Morrison, R.; Gaynor, D.; Nugent, T. A performance improvement case study in aircraft maintenance and its implications for hazard identification. Ergonomics 2010, 53, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsson, A.; Ek, Å.; Akselsson, R. Learning from incidents–A method for assessing the effectiveness of the learning cycle. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2012, 25, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunel, I. Sessional Papers Printed by Order of the House of Lords, or Presented by Royal Command; Government of Great Britain: London, UK, 1841. [Google Scholar]

- Furniss, D.; Curzon, P.; Blandford, A. Using FRAM beyond safety: A case study to explore how sociotechnical systems can flourish or stall. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 2016, 17, 507–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, E. Barriers and Accident Prevention; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, C.; Schabram, K. A Guide to Conducting a Systematic Literature Review of Information Systems Research; Sprouts Farmers Market: Chandler, AZ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, C.; Murphy, K.; Meehan, B.; Thomas, J.; Brooker, D.; Casey, D. From screening to synthesis: Using nvivo to enhance transparency in qualitative evidence synthesis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandara, W.; Furtmueller, E.; Gorbacheva, E.; Miskon, S.; Beekhuyzen, J. Achieving rigor in literature reviews: Insights from qualitative data analysis and tool-support. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 37, 154–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.; Oliver, S.; Thomas, J. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2017; pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Meline, T. Selecting studies for systematic review: Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Contemp. Issues Commun. Sci. Disord. ASHA 2006, 33, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wienen, H.C.A.; Bukhsh, F.A.; Vriezekolk, E.; Wieringa, R.J. Accident Analysis Methods and Models—A Systematic Literature Review; University of Twente, Centre for Telematics and Information Technology (CTIT): Enschede, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Maykut, P.S.; Morehouse, R. Beginning Qualitative Research: A Philosophic and Practical Guide; Falmer Press: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, D.L.; Rohleder, T.R. Learning from incidents: From normal accidents to high reliability. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2006, 22, 213–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drupsteen, L.; Groeneweg, J.; Zwetsloot, G.I. Critical steps in learning from incidents: Using learning potential in the process from reporting an incident to accident prevention. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2013, 19, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission (EU). (EU) 2018/1139 of the European Parliment and the Council of 4 July 2018 on common rules in trhe field of civil aviation and establishing a European Union Aviation Safety Agency, and amending Regulations (EC) No 2111/2005, (EC) No 1008/2008, (EU) No 996/2010, EU376/2014 and Directives 2014/30/EU of the European Parliment and the Council, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 of the European Parliment and of the Council and Council Regulation (EEC) No 3922/91; European Commission (EU): Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, A.-K.; Hansson, S.O.; Rollenhagen, C. Learning from accidents–What more do we need to know? Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukic, D.; Littlejohn, A.; Margaryan, A. A framework for learning from incidents in the workplace. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, L. Organizational dilemmas as barriers to learning. Learn. Organ. 1998, 5, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, F.W. The Principles of Scientific Management; Harper & Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, R. Editor’s Comments: The rhetoric of positivism versus interpretivism: A personal view. MIS Q. 2004, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Walsham, G. Interpretive case studies in IS research: Nature and method. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 1995, 4, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, B.J. Researching Information Systems and Computing; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschheim, R. Information systems epistemology: An historical perspective. Res. Methods Inf. Syst. 1985, 9, 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt, T. Constructivist, interpretivist approaches to human inquiry. Handb. Qual. Res. 1994, 1, 118–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger, J. The methodology of focus groups: The importance of interaction between research participants. Sociol. Health Illn. 1994, 16, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogardus, E.S. Social distance in the city. Proc. Publ. Am. Sociol. Soc. 1926, 20, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, J.H.; Fontana, A. The group interview in social research. Soc. Sci. J. 1991, 28, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, R.A.; Single, H.M. Focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 1996, 8, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzi, A.V. The diagnosis of communication and trust in aviation maintenance (DiCTAM) model. Aerospace 2019, 6, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzi, A.V.; Martin, W.; Bates, P.; Murray, P. The unexplored link between communication and trust in aviation maintenance practice. Aerospace 2019, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Patton, M.Q., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QDA Training. Working with NVivo; QDA Training: Dublin, Ireland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Baskerville, R.; Pries, J.H. Short cycle time systems development. Inf. Syst. J. 2004, 14, 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, M.; Atkinson, P. Ethnography: Principles in Practice, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, L. Designing and Refining Hierarchical Coding Frames. In Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis: Theory, Methods and Practice; Udo, K., Ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1995; pp. 96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Birks, M.; Chapman, Y.; Francis, K. Memoing in qualitative research: Probing data and processes. J. Res. Nurs. 2008, 13, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. The Logical Categories of Learning and Communication. In Steps to an Ecology of Mind; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1972; pp. 279–308. [Google Scholar]

- Bedwell, W.L.; Salas, E. Computer-based training: Capitalizing on lessons learned. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2010, 14, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, E.L. Fundamental theorems in judging men. J. Appl. Psychol. 1918, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Included | Excluded |

|---|---|

| Research studies | Literature reviews |

| Qualitative and mixed methods | Quantitative methods |

| Perceptions and experiences | Focused on decision-making and legislative requirements |

| Reference to just culture | Not about “no blame” or a punitive approach |

| High reliability settings | Non high reliability settings |

| Published post 1992 | |

| Peer-reviewed publications | |

| Industry based settings | |

| Original studies |

| Codification Theme | Description | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Root Cause | Reason to establish causation | Focus Group |

| Reporting | Value of reporting to learning from incidents | Focus Group |

| Learning from Incidents | Outcomes of learning from incidents | Literature Analysis |

| Just culture | Impact of just culture on learning from incidents | Literature Analysis |

| Precursors | Contribution of precursors to learning from incidents | Literature Analysis |

| Participant Roles | Number |

|---|---|

| Category B1 Engineer | 4 |

| Supervisor | 3 |

| Category A Mechanic | 3 |

| Quality Assurance Engineer | 3 |

| Category B2 Engineer | 2 |

| Shift Controller | 2 |

| Contract Composite Inspector | 1 |

| Inspector | 1 |

| Aeronautical Engineer | 1 |

| Category B1/B2 Engineer | 1 |

| Maintenance Manager | 1 |

| Technical Safety Manager | 1 |

| Technical Services Manager | 1 |

| Line Maintenance Manager | 1 |

| Deputy Quality Manager | 1 |

| Maintenance Control Manager | 1 |

| Maintenance Planner | 1 |

| Maintenance Safety Officer | 1 |

| Apprentice Technician | 1 |

| Analytical Process (Braun and Clarke, 2006) [47] | Practical application of Braun and Clarke in Conjunction with NVivo | Strategic Objective | Iterative Process Throughout Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Familiarizing yourself with the data | Transcribing data (if necessary), reading and re-reading the data, noting down initial ideas. Import data into the NVivo data management tool | Data Management (Open and hierarchal coding through NVIVO)  Descriptive Accounts (Reordering, ‘coding on’ and annotating through NVIVO)  Explanatory Accounts (Extrapolating deeper meaning, drafting summary statements and analytical memos through NVIVO) | Assigning data to refined concepts to portray meaning Refining and distilling more abstract concepts  Assigning data to themes/concepts to portray meaning  Assigning meaning  Generating themes and concepts |

| 2. Generating initial codes | Phase 2. Open Coding:Coding interesting features of the data in a systematic fashion across the entire data set, collecting data relevant to each code | ||

| 3. Searching for themes | Phase 3. Categorization of Codes:Collating codes into potential themes, gathering all data relevant to each potential theme | ||

| 4. Reviewing themes | Phase 4.Coding on:Checking if the themes work in relation to the coded extracts (level 1) and the entire data set (level 2), generating a thematic “map” of the analysis | ||

| 5. Defining and naming themes | Phase 5. Data Reduction:On-going analysis to refine the specifics of each theme, and the overall story (storylines) the analysis tells, generating clear definitions and names for each theme | ||

| 6. Producing the report | Phase 6. Generating Analytical Memos. Phase 7. —Testing and Validating. Phase 8. Synthesizing Analytical Memos. The final opportunity for analysis. Selection of vivid, compelling extract examples, final analysis of selected extracts, relating back of the analysis to the research question and literature, producing a scholarly report of the analysis [47,48] |

| Learning from Incidents 1 | Learning Process 2 | Learning Product 3 |

|---|---|---|

| The decision to report an incident can be impacted by the perceived commercial pressure and the potential for embarrassment associated with making a mistake, amongst front line maintenance staff. | The release of a safe aviation product is the primary goal all operational maintenance and management staff espouse to. | In the organizations supporting the study, it was apparent that incidents are managed with the support of a consistent life-cycle methodology. |

| Identifying and understanding organizational behavioral and human factors are important elements affecting decisions to report. | Single-loop learning is a level of learning that can exist in a dynamic operational environment where a “find and fix” ethos exists. | Learning products that arise from the managed lifecycle of an incident are intended to impart sufficient learning to prevent recurrence or occurrence of same or similar events. |

| Inadequately resourced investigation and follow up of incidents does not support the determination of accurate event causation and measures to prevent similar incidents reoccurring. | The mandatory human factors continuation training program is considered by study participants to be an effective enabler of double-loop learning. | While aircraft manufacturers generally provide feedback on notified incidents, component manufacturers provide less feedback with little or no feedback arising from aviation authorities on submitted reports in the jurisdiction of the study. |

| The recognition of the extended impact of under-reporting on “levels of learning” is not always a priority in some organizations. | Evidence amongst study participants where a review of single and double-loop learning within organizations was not available during the study. | The cost of classroom delivered continuation training is a primary consideration for most organizations. |

| The absence of a potential learning product that results from effective reporting is an impediment when attempting to gauge the effectiveness of learning. | No formal requirement for competence in the areas of learning for managers and accountable persons exists in EU regulation 1321/2014. | Computer based training is an option that is under trial by some organizations but there are concerns amongst operational staff regarding its overall effectiveness in its current form. |

| Pressure to prematurely close incident reports does not promote thorough event causation and measures to prevent similar incidents reoccurring. | No competence requirements for staff involved in the development or delivery of formal human factors continuation training programs. | Just culture has a positive impact on reporting rates. |

| Feedback to staff on incident causation factors from an information and learning perspective is important. | ||

| Poorly designed continuation training syllabi do not support effective learning. | ||

| Timely follow up to incident reports supports more effective learning outputs from the reporting process. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Clare, J.; Kourousis, K.I. Learning from Incidents: A Qualitative Study in the Continuing Airworthiness Sector. Aerospace 2021, 8, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace8020027

Clare J, Kourousis KI. Learning from Incidents: A Qualitative Study in the Continuing Airworthiness Sector. Aerospace. 2021; 8(2):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace8020027

Chicago/Turabian StyleClare, James, and Kyriakos I. Kourousis. 2021. "Learning from Incidents: A Qualitative Study in the Continuing Airworthiness Sector" Aerospace 8, no. 2: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace8020027

APA StyleClare, J., & Kourousis, K. I. (2021). Learning from Incidents: A Qualitative Study in the Continuing Airworthiness Sector. Aerospace, 8(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace8020027