3.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

At the beginning of the survey, a question was used to find out in which area the subjects follow influencers or also consider them useful. With the help of the function “Define variable sets for multiple answers”, it was examined which subject areas were most frequently indicated. The first places are as visible in

Figure 1: food/nutrition in first place with 185 answers, followed by sports with 178 and travel with 170 answers and fashion with 139 answers. Surprisingly, despite the high female participation rate, beauty is in 5th place with only 100 responses.

The results are almost identical to the surveys conducted by PwC and Mindshare, with the exception of beauty, as this topic is not among the top three in this survey. As expected, the topic “finance” is in last place with 31 responses, again an indication that influencer marketing is not yet used in this sector. For this reason it does not yet have any significance for followers, and there seems to be potential for this new topic in which influencers can reposition themselves.

On the topics of credibility and trust (questions 3–11), participants were shown specific statements to rate on a 5-point Likert scale from “1 = agree” to “5 = disagree.” The results show that the majority of participants answered “partly agree” when it comes to whether respondents were interested in advertised products (49.7%), believe the judgment of influencers (37.7%), can be convinced to buy the product (39.1%) and in that sense, also see influencers as role models (44.7%). In contrast, there are only 58 participants (19.2%) who see influencers as a person of trust—30.5% of respondents do not trust the influencers at all. Almost 50% of the participants could not decide whether they consider influencers to be credible or not.

The second focus of the survey was on financial products. The first three statements, which were to be rated on a 5-point Likert scale, were an attempt to evaluate the respondents’ insights into their interest in and involvement with financial products. Several studies conducted, including those by Erste Bank and BAWAG, show that financial literacy and knowledge of financial products are weak among young adults (

BAWAG Group 2019;

Erste Bank der österreichischen Sparkassen 2018). As expected, the interest in financial topics increases on average the older the respondent is. In the smaller group of 18–19 years, no one agreed to be very interested in or concerned with financial products.

Table 1 and

Table 2 summarize these results.

The higher the school-leaving qualification, the more likely the respondents are to be interested in financial products or to deal with them. Among university graduates, however, there is a tendency for higher interest in, than actual involvement with, financial products. It can therefore be concluded that the interest undoubtedly exists, but that the appropriate form of marketing or information is still insufficient for those people to actually engage with financial products.

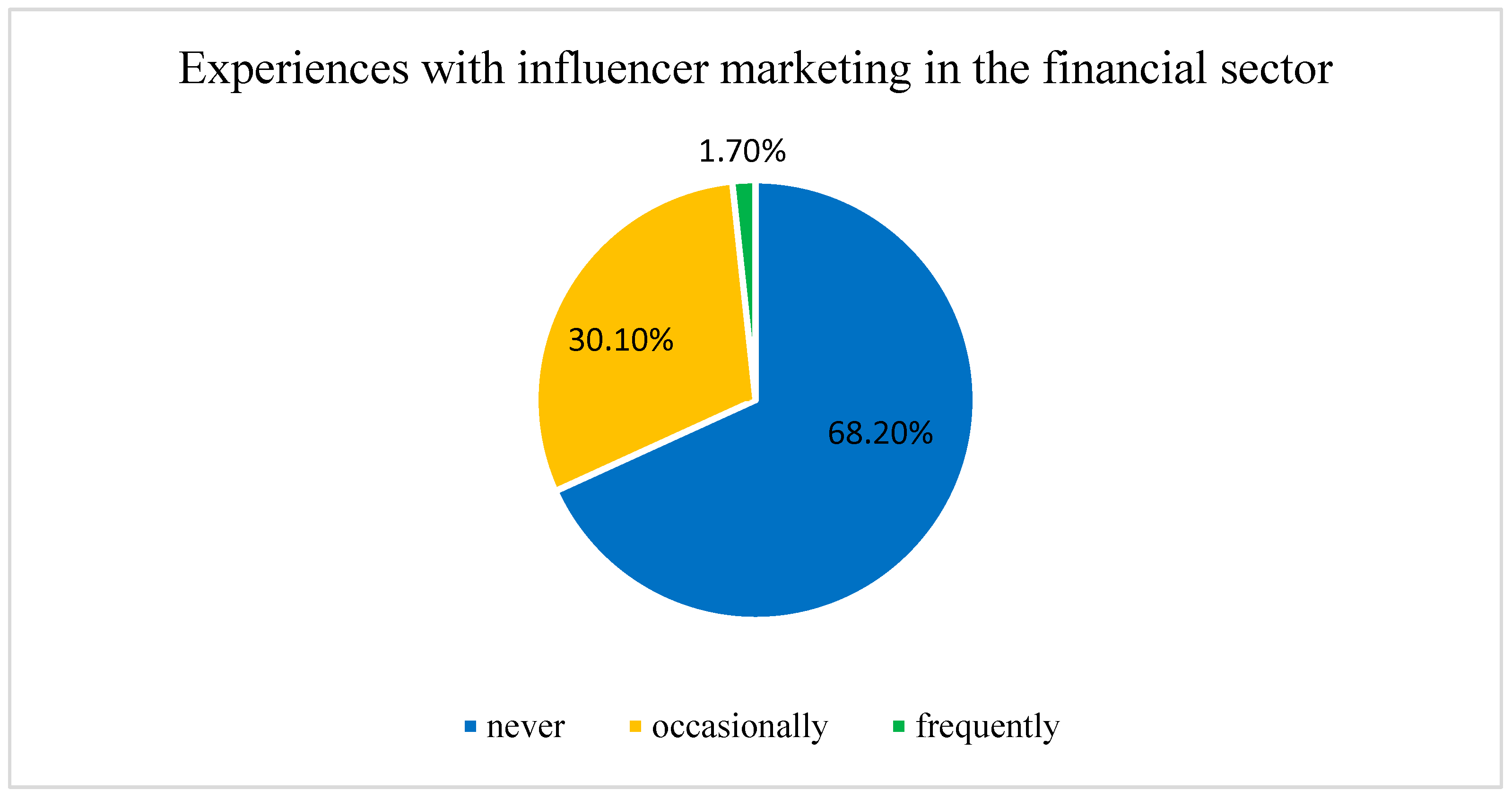

At the beginning of the second part of the survey, participants were asked whether they had already noticed influencer marketing by banks. A clear picture emerged here, confirming that there are no real influencers for the financial sector to date.

Figure 2 illustrates the result, which states that 68.2% of the respondents have not yet recognized influencer marketing in the financial sector, 30.1% did so occasionally, and only 1.7% did frequently. At first glance, it seems inconclusive that almost a third stated that they have occasionally perceived influencer marketing for financial products, although on the part of the literature it was repeatedly mentioned that there is hardly any influencer marketing of Austrian banks. From a theoretical point of view this is true, yet three possible reasons can be given in practice that can explain the 30.1%. First, there have been isolated collaborations between an influencer and a bank in the past, for example the cooperation with Tatjana Kreuzmayr and Erste Bank. Secondly, it is possible that the respondents also understand influencer marketing to mean web blogs and financial blogs, of which there are quite a few that provide information about financial products.

Probably the most important information for our study comes from the question of whether influencers should advertise financial products, and whether there is approval for this on the part of followers.

However, we find that there is currently a clear opinion against influencer marketing as a form of marketing for financial products (70%). Only 30% see a new opportunity in this form of marketing. In a next step, it was analyzed whether there are differences between the age groups. The results show that in almost every age group, more people reject influencer marketing in banks. The outliers here were test subjects aged 18 or 19—here the “yes/no” answers were almost the same or the same. Even if it is clear at first glance that influencer marketing is not desired, the 30% who agreed should not be underestimated—it is still more than a quarter who are in favor of the new form of marketing. Thus, this marketing strategy can be successful. However, the aversive tendency towards influencers is also reflected by 76.5% of the respondents who would not or rather not buy financial products even if they were recommended by influencers.

For further analysis, the subjects were divided into two groups—the division was based on question 4 of the survey: Have you bought products recommended by influencers in the last two years?

group 1 “yes, already bought at least one product” (n = 198)

group 2 “no, never bought a product before” (n = 194)

If we compare both groups in terms of their behavior and their attitude toward influencer marketing in banks, a surprising picture emerges. Since 65.5% of the test subjects already have experience with influencer marketing, one could assume that they also approve of influencer marketing for financial products (198, 65.5% of 302). However, the results show that only 32% of group 1, who have experience with the purchase of advertised products through influencers, also consider influencer marketing useful for banks and 68% are against influencer marketing in this area. A similar result can also be seen in group 2, where 72% of the people questioned are against influencer marketing. This is an obvious result, since those people have not yet purchased any products advertised by influencers and therefore have no experience with them. For the second group, the result could be explained by the lack of experience in this respect.

In the following analysis, groups 1 and 2 were also compared with the results of the questions whether they would buy or deal with financial products advertised by influencers. To recall the descriptive results: 3/4 of all respondents stated that they would not/rather not buy financial products, even if they were presented and recommended by influencers. The new result shows a similar picture, with just under 74% of group 1 fully disagreeing with the statements that they would buy financial products advertised by influencers. There is no respondent in either group 1 or group 2 who fully agreed to the statement.

Therefore, we further analyze why some people buy influencer products in general but do not want financial products promoted by influencers. Since the result is very clear, both groups were additionally compared with the results regarding the engagement with financial products. Possibly, the purchase of financial products is too risky, and people therefore tend to engage more with the products before finally buying.

The results confirm the assumptions: People in group 1 are tempted to look more closely at financial products when the financial products are presented by influencers. Four subjects answered, “fully agree”. Overall, as many as 31% agreed and just under 44% of them disagreed. Based on this, it is possible that influencers are considered an important source of information for group 1—however, this assumption cannot be confirmed, as 36.9% of group 1 “strongly disagree”. Even more skeptical are the people of group 2, who have no experience with influencer products so far; here, too, the subjects who do not allow themselves to be enticed by influencers to engage with financial products are in the majority (69.2%).

Thus, it can already be concluded from the descriptive results that for those subjects in group 2, influencer marketing is not the right strategy to get in touch with them to entice them to buy or deal with financial products. For people questioned who are already experienced with advertised products, it is shown that they can be reached with this type of marketing, but for topics which were not covered so far by influencer marketing, it is more a type of incentive for an engagement, but not for a final purchase. Here, however, the question cannot be answered whether the failure to make a purchase is related to the serious topic of financial products, or the reason that influencer marketing has not yet been used for financial products and therefore lacks experience.

3.2.2. Hypotheses Testing

To test our hypotheses, we apply different statistical tests depending on the scale levels. The significance level was assumed to be an error probability of 5%, which means that a result can be considered significant if p (error probability) is less than or equal to 5% (p ≤ 0.05).

Table 3 shows the result with

r value of 0.246. The

p-value of 0.000 is smaller than the established 0.05 (

p < 0.05) and therefore the result is significant. It follows that we can reject H0. Thus, a relationship between influencer information acquisition and engagement with financial products can be confirmed.

To answer H2, the first step was to create a new variable for buying behavior called “Buying behavior NEW”. This new variable is composed of two items from the questionnaire “If the influencer convinces me, I buy the product” and “It happens that I am influenced”. The dependent variable “Buying behavior _NEW” and the independent variable “Credibility”, both of which are again interval scaled and have a metric scale level, are therefore subjected to a Pearson correlation test to show whether there is a correlation and whether the hypothesis is consequently accepted or rejected.

Table 4 shows that we can accept H1, since the two-sided significance has a value of 0.000 and is thus lower than the required 5%. (

p < 0.05). Furthermore, there is a positive medium correlation (

r = 0.479) between the variables. Consequently, it can be confirmed that the more credible an influencer is, the easier it is for his or her followers to be influenced in their purchasing behavior.

Obviously, our result is significant. Furthermore, there is a moderately weak positive correlation (

r = 0.310) between credibility and the consequence of buying a financial product advertised or recommended by influencers (

Table 5). Therefore, we reject H0 again and we can accept the hypothesis that the more credible an influencer is, the more likely people are to buy the financial products advertised.

H4 is basically the same as H3, except that in this case we wanted to find out whether people also engage with financial products if they consider an influencer to be trustworthy. As already described in the testing of the third hypothesis, the variable “engagement with advertised financial products” is the dependent variable, which is interval-scaled, and the variable “trusted person”, which is new in this case, is also interval-scaled with a metric scale level.

As with the previous hypothesis, the result is significant (

p = 0.000) and there is a weak positive correlation (

r = 0.293) between the two variables (

Table 6). It follows that H0 can be rejected and H1 is accepted, which states that people are more likely to engage in the advertised financial products if they consider an influencer to be trustworthy.

H5 is also a correlation hypothesis, consisting of the independent variable “influencers more trustworthy than traditional advertising” and the dependent variable “buy advertised financial product”. Both variables are interval-scaled and therefore have a metric scale level, which is why a Pearson correlation test is used.

We can see that the variables are positively correlated (

r = 0.261) and the

p-value is 0.000 (

p < 0.05) and thus (

Table 7), significant, which leads to rejecting H0 and confirming H1.

To be able to test H6 which is a difference hypothesis, a new variable “purchase_influencer_reviewed_products_new” was created in the first step to generate two independent samples. The response options “yes, once”; “yes, 2–10 times”; “yes, more than 10 times” were coded into group 1 “yes, already bought at least 1 product” as well as “no, never bought a product” into group 2.

The hypothesis includes the new nominally scaled variable as well as an interval scaled variable “purchase of advertised financial products.” These two scale levels require the t-test. Before this test can be performed, the mean of both independent samples is first tested for the dependent variable “buy advertised financial product”. The results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test applied to both samples show that there is no normal distribution in either sample (

Figure 3).

Since there is no normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney U test is used for indepen-dent samples. The analysis shows that there is a significant difference between the two control groups (already bought a product, not yet bought a product) regarding the willingness to buy an advertised financial product (

Table 8). We can see that the asymptotic significance has a value of 0.037, which is less than 0.05. The difference between the two control groups is therefore not significant. The results show that we can confirm H6. That is, people who have already bought influencer-promoted products in the past two years also tend to buy advertised financial products. Exactly the same applies to people who have not yet bought any products—they also tend not to buy any advertised financial products in the future.