Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Prices in Nigeria—A Threshold Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Theoretical Framework

3.2. Empirical Model Specification

3.3. Estimation Technique

3.4. Data Sources and Description

4. Empirical Results and Discussion

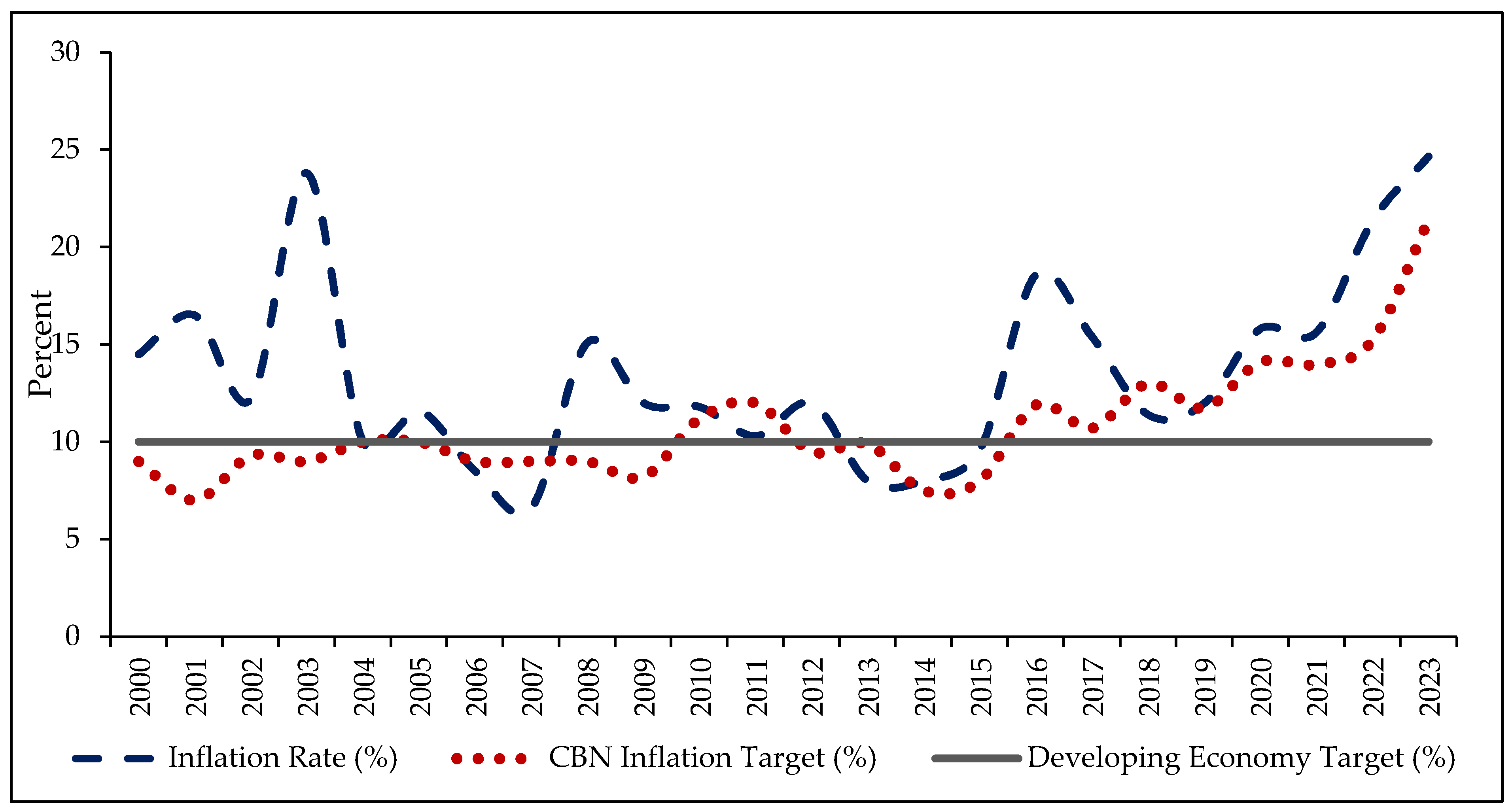

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

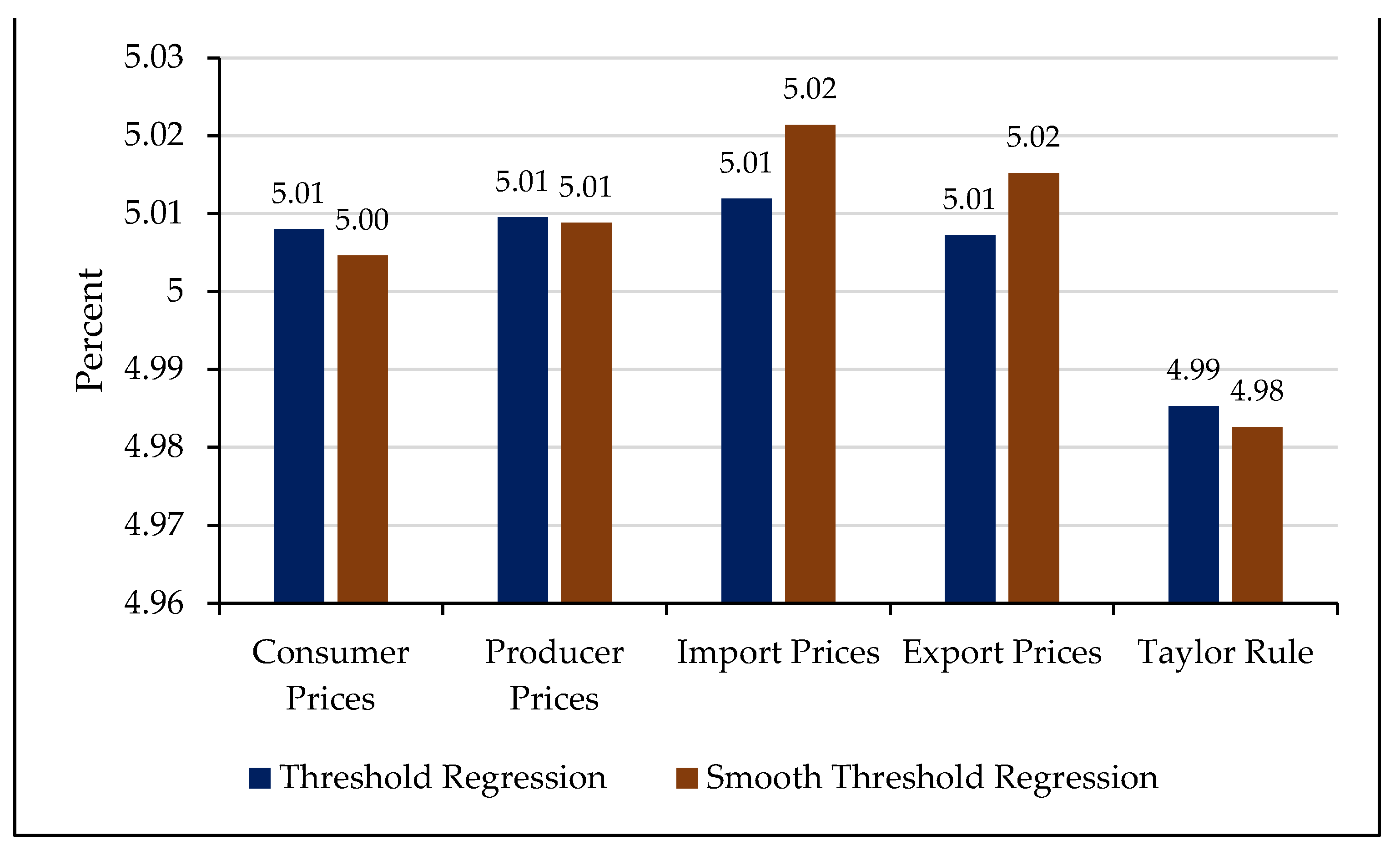

4.2. Main Analysis

4.2.1. The Wald Test

4.2.2. Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Producer and Consumer Prices

4.2.3. Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Export and Import Prices

4.2.4. Exchange Rate Depreciation within the Taylor Rule of Monetary Policy

4.3. Sub-Sample Analysis (2000–2015) and a Test for the Sensitivity of the Results

5. Discussion of Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Consumer Prices | Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Producer Prices | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | |||||

| Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | |

| LEXC | 0.7322 | 0.8112 | 0.7299 | 0.8298 | 0.7117 | 1.4819 | 0.7398 | 1.5217 |

| (0.0046) *** | (0.0000) *** | (0.0009) *** | (0.0000) *** | (0.0002) *** | (0.0009) *** | (0.0059) *** | (0.0000) *** | |

| Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | |||||

| LEXC(-1) | 0.0360 ** | (0.0178) | 0.0280 *** | (0.0125) | 0.1596 * | (0.0820) | 0.1423 * | (0.0800) |

| MPR | −0.0355 *** | (0.0018) | −0.0340 *** | (0.0009) | −0.0844 ** | (0.0114) | −0.0671 ** | (0.0167) |

| MPR(-1) | −0.0249 ** | (0.0390) | −0.0278 * | (0.0786) | −0.0391 ** | (0.0499) | −0.0304 ** | (0.0333) |

| RGDPG | 0.0019 *** | (0.0081) | 0.0063 *** | (0.0096) | 0.0092 *** | (0.0056) | 0.0097 *** | (0.0099) |

| RGDPG(-1) | 0.0181 *** | (0.0045) | 0.0069 ** | (0.0191) | 0.0061 *** | (0.0099) | 0.0090 *** | (0.0088) |

| C | −0.8008 * | (0.0993) | 2.2000 ** | (0.0139) | ||||

| Threshold | 5.008 | 5.0059 *** | (0.0000) | 5.0097 | 5.0086 *** | (0.0000) | ||

| SSR | 1.1818 | 1.8990 | 11.9899 | 11.7899 | ||||

| Regime | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Serial Correlation | 0.5008 | 0.7191 | 0.9100 | 0.6709 | ||||

| Heteroscedasticity | 0.3684 | 0.6950 | 0.9956 | 0.6971 | ||||

| Normality Test | 0.8912 | 0.6865 | 0.7877 | 0.8610 | ||||

| Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Export Prices | Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Import Prices | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | |||||

| Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | |

| LEXC | 0.6319 *** | 1.5722 *** | 0.6319 *** | 1.6059 *** | 0.7716 *** | 1.6500 ** | 0.7696 ** | 1.6490 *** |

| (0.0057) | (0.0085) | (0.0001) | (0.0000) | (0.0091) | (0.0308) | (0.0426) | (0.0000) | |

| Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | |||||

| LEXC(-1) | 0.2720 ** | (0.0471) | 0.8665 * | (0.0642) | 0.1440 * | (0.0665) | 0.2381 * | (0.0518) |

| MPR | −0.0075 ** | (0.0481) | −0.0223 ** | (0.0205) | −0.0180 ** | (0.0135) | −0.0239 * | (0.0734) |

| MPR(-1) | −0.0137 ** | (0.0324) | −0.0446 ** | (0.0176) | −0.0181 ** | (0.0147) | −0.0268 ** | (0.0474) |

| RGDPG | 0.0060 ** | (0.0223) | 0.0167 ** | (0.0127) | 0.0016 * | (0.0719) | 0.0004 * | (0.0926) |

| RGDPG(-1) | 0.0017 ** | (0.0286) | 0.0017 * | (0.0797) | 0.0041 ** | (0.0347) | 0.0028 * | (0.0562) |

| C | 3.1965 *** | (0.0000) | 3.1523 *** | (0.0000) | 1.6324 *** | (0.0058) | 1.6459 *** | (0.0051) |

| Threshold | 5.0072 | 5.0152 *** | (0.0000) | 5.0119 | 5.0214 *** | (0.0000) | ||

| SSR | 1.6853 | 2.85 | 1.3506 | 3.28 | ||||

| Regime | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Serial Correlation | 0.1657 | 0.277 | 0.138 | 0.1267 | ||||

| Heteroscedasticity | 0.334 | 0.6018 | 0.614 | 0.5476 | ||||

| Normality Test | 0.812 | 0.7657 | 0.3681 | 0.6456 | ||||

| Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | |

| LEXC | 3.1984 ** | 5.8567 ** | 1.70016685 *** | 5.0711 *** |

| (0.0131) | (0.0192) | (0.0089) | (0.0000) | |

| Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | |||

| INFGAP | 0.0129 * | (0.0790) | 0.2000 ** | (0.0289) |

| YGAP | 0.0279 * | (0.0511) | 0.0800 ** | (0.0177) |

| MPR(-1) | −0.9089 *** | (0.0000) | −0.2678 ** | (0.0212) |

| LEXC(-1) | 3.0020 ** | (0.0299) | 1.1201 ** | (0.0198) |

| C | −1.7978 ** | (0.0311) | −6.8496 ** | (0.0333) |

| Threshold | 4.9918 | 4.9732 | ||

| SSR | 102.3137 | 600.3189 | ||

| Regime | 2 | 2 | ||

| Serial Correlation | 0.8770 | 0.9543 | ||

| Heteroscedasticity | 0.6657 | 0.4192 | ||

| Normality Test | 0.1908 | 0.2749 | ||

References

- Abango, Mohammed A., Hadrat Yusif, and Adam Issifu. 2019. Monetary aggregates targeting, inflation targeting and inflation stabilization in Ghana. African Development Review 31: 448–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedokun, Adebayo S., Charles O. Ogbaekirigwe, and Kehinde. A. Tiamiyu. 2022. Exchange Rate Pass-Through to Inflation: Symmetric and Asymmetric Effects of Monetary Environment in Nigeria. Acta Universitatis Danubius 18: 24–41. [Google Scholar]

- Adekunle, Wasiu, Kehinde A. Tiamiyu, and Taiwo H. Odugbemi. 2019. Exchange Rate Pass-through to Consumer Prices in Nigeria: An Asymmetric Approach. Bingham Journal of Economics and Allied Studies 2: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Adelowokan, Oluwaseyi A. 2012. Exchange Rate Pass-Through in Nigeria: Dynamic Evidence. European Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 16: 785–801. [Google Scholar]

- Alagidede, Paul, and Muazu Ibrahim. 2017. On the causes and effects of exchange rate volatility on economic growth: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of African Business 18: 169–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleem, Abdul, and Amine Lahiani. 2014. Monetary policy credibility and exchange rate pass-through: Some evidence from emerging countries. Economic Modelling 43: 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Syed Zahid, and Sajid Anwar. 2016. Can exchange rate pass-through explain the price puzzle? Economics Letters 145: 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghelescu, Cristina. 2022. Shock-Dependent Exchange Rate Pass-Through into Different Measures of Price Indices in the Case of Romania. Romanian Journal of Economic Forecasting XXV: 88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, Raphael A., and Raphael S. Schoenle. 2016. Market structure and exchange rate pass-through. Journal of International Economics 98: 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bada, Abiodun S., Ajibola I. Olufemi, Inuwa A. Tata, Idowu Peters, Sani Bawa, Anigwe J. Onwubiko, and Udoko C. Onyowo. 2016. Exchange Rate Pass-through to Inflation in Nigeria. CBN Journal of Applied Statistics 7: 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bandt, Olivier, and Tovonony Maherizo Razafindrabe. 2014. Exchange rate pass-through to import prices in the Euro-area: A multi-currency investigation. International Economics 138: 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, Usman A., and Aliyu R. Sanusi. 2019. Inflation Dynamics and Exchange Rate Pass-Through in Nigeria: Evidence from Augmented Nonlinear New Keynesian Philips Curve. CBN Journal of Applied Statistics 10: 109–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernanke, Ben S., Tomas Laubach, Frederic S. Mishkin, and Adam S. Posen. 2018. Inflation Targeting: Lessons from the International Experience. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, Javed A., Md Zulquar Nain, and Sajad A. Bhat. 2022. Exchange rate pass-through to consumer prices in India—nonlinear evidence from a smooth transition model. International Journal of Finance & Economics 29: 927–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, G. Maria, Mohamad H. Helmi, Abdurrahman N. Çatık, Faek M. Ali, and Coskun Akdeniz. 2018. Monetary policy rules in emerging countries: Is there an augmented nonlinear Taylor rule? Economic Modelling 72: 306–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, Camila. 2020. Industry heterogeneity and exchange rate pass-through. Journal of International Money and Finance 106: 102182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellares, Renzo, and Hiroshi Toma. 2020. Effects of a mandatory local currency pricing law on the exchange rate pass-through. Journal of International Money and Finance 106: 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN). 2021. Inflation Targeting as a Monetary Policy Framework. Available online: https://www.cbn.gov.ng/Out/2022/MPD/Series%2012.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN). 2023. CBN Statistical Bulletin, 2023 Edition. Available online: https://www.cbn.gov.ng/documents/QuarterlyStatbulletin.asp (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN). 2024. Weighted Average Rate—Nigerian Foreign Exchange Market (NFEM). Available online: https://www.cbn.gov.ng/rates/ExchRateByCurrency.asp (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Cheikh, N. B., and B. Y. Zaied. 2020. Revisiting the pass-through of exchange rate in the transition economies: New evidence from new EU member states. Journal of International Money and Finance 100: 102093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheikh, N. Ben, and Wael Louhichi. 2016. Revisiting the role of inflation environment in exchange rate pass-through: A panel threshold approach. Economic Modelling 52: 233–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhri, Ehsan U., Hamid Faruqee, and Dalia S. Hakura. 2005. Explaining the exchange rate pass through in different prices. Journal of International Economics 65: 349–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mendonça, Helder F., and Bruno P. Tiberto. 2017. Effect of credibility and exchange rate pass-through on inflation: An assessment for developing countries. International Review of Economics and Finance 50: 196–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, Michael B., and James Yetman. 2010. Price adjustment and exchange rate pass-through. Journal of International Money and Finance 29: 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, Michael B., Charles Engel, and Peter E. Storgaard. 2004. Endogenous exchange rate pass-through when nominal prices are set in advance. Journal of International Economics 63: 263–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornbusch, Rudiger. 1987. Exchange rates and prices. American Economic Review 77: 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Fandamu, Humphrey, Manenga Ndulo, Dale Mudenda, and Mercy Fandamu. 2023. Asymmetric Exchange Rate Pass Through to Consumer Prices: Evidence from Zambia. Foreign Trade Review 58: 504–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Nga N., Loan V. T. Kim, An P. Hoang, and Cuong T. Q. Khanh. 2022. Understanding exchange rate pass-through in Vietnam. Cogent Economics & Finance 10: 2139916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Rodrígueza, Rebeca, and Amalia Morales-Zumaquero. 2016. A new look at exchange rate pass-through in the G-7 countries. Journal of Policy Modeling 38: 985–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabundi, Alain, and Montfort Mlachila. 2019. The role of monetary policy credibility in explaining the decline in exchange rate pass-through in South Africa. Economic Modelling 79: 173–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassi, Diby F., Gang Sun, Ning Ding, Dilesha N. Rathnayake, and Guy R. Assamoi. 2019. Asymmetry in exchange rate pass-through to consumer prices: Evidence from emerging and developing Asian countries. Economic Analysis and Policy 62: 357–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khundrakpam, Jeevan K. 2008. Have Economic Reforms Affected Exchange Rate Pass-Through to Prices in India? Economic and Political Weekly 43: 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kiliç, Rehim. 2016. Regime-dependent exchange-rate pass-through to import prices. International Review of Economics and Finance 41: 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Villavicencio, Antonia, and Marc Pourroy. 2019. Does inflation targeting always matter for the ERPT? A robust approach. Journal of Macroeconomics 60: 360–77. [Google Scholar]

- López-Villavicencio, Antonia, and Valerie Mignon. 2017. Exchange rate pass-through in emerging countries: Do the inflation environment, monetary policy regime and central bank behavior matter? Journal of International Money and Finance 79: 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, Qaiser, Kasim Mansur, and Fumitaka Furuoka. 2009. Inflation and economic growth in Malaysia: A threshold regression approach. ASEAN Economic Bulletin 26: 180–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, Mohammad A., and Xuan V. Vo. 2020. A quarter century of inflation targeting & structural change in exchange rate pass-through: Evidence from the first three movers. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 54: 42–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, Mohammad A., Toan L. D. Huynh, and Xuan V. Vo. 2020. Exchange rate pass-through & management of inflation expectations in a small open inflation targeting economy. International Review of Economics and Finance 69: 178–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundipe, Adeyemi A., and Samuel Egbetokun. 2013. Exchange Rate Pass-through to Consumer Prices in Nigeria. European Scientific Journal 9: 110–23. [Google Scholar]

- Oktay, Alex. 2022. Heterogeneity in the exchange rate pass-through to consumer prices: The Swiss franc appreciation of 2015. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics 158: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyadeyi, Olajide O. 2022a. A systematic and non-systematic approach to monetary policy shocks and monetary transmission process in Nigeria. Journal of Economics and International Finance 14: 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyadeyi, Olajide O. 2022b. Interest Rate Pass-Through in Nigeria. Journal of Economics and Development Studies 10: 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Oyadeyi, Olajide O. 2024a. The Velocity of Money and Lessons for Monetary Policy in Nigeria: An Application of the Quantile ARDL Approach. Journal of the Knowledge Economy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyadeyi, Olajide O. 2024b. Financial Development, Monetary Policy and Monetary Transmission Mechanism—An Asymmetric ARDL Analysis. Economies 12: 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyinlola, Mutiu A., and Musibau A. Babatunde. 2009. A Bound Testing Analysis of Exchange Rate Pass through to Aggregate Import prices in Nigeria: 1980–2006. Journal of Economic Development 34: 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir, Metin. 2020. The role of exchange rate in inflation targeting: The case of Turkey. Applied Economics 52: 3138–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, Ibrahim, and Lutfi Erden. 2015. Time-varying nature and macroeconomic determinants of exchange rate pass-through. International Review of Economics and Finance 38: 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigobon, Roberto. 2020. What can online prices teach us about exchange rate pass-through? Journal of International Money and Finance 106: 102179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takhtamanova, Yelana F. 2010. Understanding changes in exchange rate pass-through. Journal of Macroeconomics 32: 1118–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, John B. 1993. Discretion versus policy rules in practice. In Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy. Pittsburgh: North-Holland, vol. 39, pp. 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Howell. 1978. On a Threshold Model in Pattern Recognition and Signal Processing. Edited by C. H. Chen. Amsterdam: Sijhoff & Noordhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Valogo, Matthew K., Emmanuel Duodu, Hadrat Yusif, and Samuel T. Baidoo. 2023. Effect of exchange rate on inflation in the inflation targeting framework: Is the threshold level relevant? Research in Globalization 6: 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, Abraham. 1943. Tests of statistical hypotheses concerning several parameters when the number of observations is large. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 54: 426–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigit, Özlem. 2022. Exchange Rate Pass-Through and Historical Decomposition of Inflation in Turkiye. Ekonomik Yaklaşım 33: 379–428. [Google Scholar]

| Variables and Abbreviation | Measurements | Expected Sign | Sources | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Price (LCPI) | The log of consumer price index | - | CBN Bulletin 2023 | (Ozdemir 2020; Valogo et al. 2023; Aleem and Lahiani 2014) |

| Producer Price (LPPI) | The log of GDP Deflator | - | CBN Bulletin 2023 | (Jiménez-Rodrígueza and Morales-Zumaquero 2016; Casas 2020) |

| Export Price (LEPI) | The log of export price index | - | CBN Bulletin 2023 | (Jiménez-Rodrígueza and Morales-Zumaquero 2016; Casas 2020) |

| Import Price (LIPI) | The log of import price index | - | CBN Bulletin 2023 | (Ozdemir 2020; Valogo et al. 2023; Aleem and Lahiani 2014) |

| Exchange Rate (LEXC) | The log of nominal exchange rate | Positive on prices and the policy rate | CBN Bulletin 2023 | (Ozdemir 2020; Valogo et al. 2023; Aleem and Lahiani 2014) |

| Monetary Policy (MPR) | The benchmark interest rate is the percentage that central banks charge commercial banks as a fee for overnight loans of surplus cash from their reserve accounts. | Negative on prices | CBN Bulletin 2023 | (Ozdemir 2020; Valogo et al. 2023; Aleem and Lahiani 2014) |

| Inflation Gap (INFGAP) | The difference between actual inflation rate and the trended inflation rate (inf − inf*). | Positive on the policy rate | CBN Bulletin 2023 | (Ozdemir 2020; Valogo et al. 2023; Aleem and Lahiani 2014) |

| Output Gap (YGAP) | The difference between actual real GDP growth and the trended real GDP growth (y − y*) | Positive on the policy rate | CBN Bulletin 2023 | (Ozdemir 2020; Valogo et al. 2023; Aleem and Lahiani 2014) |

| Output (RGDPG) | The real GDP Growth | Negative on prices | CBN Bulletin 2023 | (Ozdemir 2020; Valogo et al. 2023) |

| LCPI | LPPI | LEPI | LIPI | MPR | INFGAP | YGAP | RGDPG | LEXC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 4.80 | 6.25 | 4.77 | 4.83 | 12.73 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.50 | 5.20 |

| Median | 4.80 | 5.48 | 4.69 | 4.71 | 13.00 | −0.40 | 0.14 | 4.74 | 5.04 |

| Maximum | 6.21 | 8.27 | 5.64 | 5.63 | 20.50 | 11.34 | 12.41 | 19.17 | 6.29 |

| Minimum | 3.40 | 4.61 | 4.23 | 4.29 | 6.00 | −12.60 | −14.12 | −7.59 | 4.61 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.76 | 1.39 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 3.25 | 3.79 | 2.96 | 3.82 | 0.45 |

| Skewness | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.91 | 1.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.44 | 0.12 | 0.76 |

| Kurtosis | 1.98 | 1.25 | 3.28 | 3.82 | 3.33 | 4.05 | 10.88 | 5.84 | 2.18 |

| Jarque-Bera | 4.01 | 12.76 | 12.86 | 18.37 | 0.47 | 4.25 | 241.05 | 31.05 | 11.42 |

| Probability | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.89 | 0.56 | 0.79 | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.31 |

| Sum | 441.4 | 574.6 | 438.7 | 444.0 | 1171.3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 413.7 | 478.1 |

| Sum Sq. Dev. | 52.2 | 176.3 | 7.5 | 6.6 | 963.8 | 1310.1 | 799.8 | 1326.7 | 18.2 |

| Observations | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 |

| Consumer Prices | Producer Prices | ||||

| Panel A | Centred | Panel B | Centred | ||

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF | Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

| C | NA | C | NA | ||

| LEXC | 4.2277 | 0.2365 | LEXC | 4.2277 | 0.2365 |

| LEXC_1 | 4.1644 | 0.2401 | LEXC_1 | 4.1644 | 0.2401 |

| MPR | 9.3494 | 0.1070 | MPR | 9.3494 | 0.1070 |

| MPR_1 | 9.1451 | 0.1093 | MPR_1 | 9.1451 | 0.1093 |

| RGDPG | 1.0881 | 0.9191 | RGDPG | 1.0881 | 0.9191 |

| RGDPG_1 | 1.1353 | 0.8808 | RGDPG_1 | 1.1353 | 0.8808 |

| Export Prices | Import Prices | ||||

| Panel C | Centred | Panel D | Centred | ||

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF | Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

| C | NA | C | NA | ||

| LEXC | 4.2277 | 0.2365 | LEXC | 4.2277 | 0.2365 |

| LEXC_1 | 4.1644 | 0.2401 | LEXC_1 | 4.1644 | 0.2401 |

| MPR | 3.3494 | 0.1070 | MPR | 3.3494 | 0.1070 |

| MPR_1 | 3.1451 | 0.1093 | MPR_1 | 3.1451 | 0.1093 |

| RGDPG | 1.0881 | 0.9191 | RGDPG | 1.0881 | 0.9191 |

| RGDPG_1 | 1.1353 | 0.8808 | RGDPG_1 | 1.1353 | 0.8808 |

| Taylor Rule | |||||

| Panel E | Centred | ||||

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF | |||

| C | NA | ||||

| LEXC | 4.3638 | 0.2292 | |||

| INFGAP | 1.0725 | 0.9324 | |||

| YGAP | 1.0757 | 0.9296 | |||

| MPR_1 | 1.2734 | 0.7853 | |||

| LEXC_1 | 4.0402 | 0.2475 | |||

| Variables | ADF | PP | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| I(0) | I(0) | ||

| LCPI | −3.7164 *** | −10.3617 *** | Stationary |

| LPPI | −9.3344 *** | −9.3344 *** | Stationary |

| LEPI | −11.5473 *** | −18.3423 *** | Stationary |

| LIPI | −10.1019 *** | −11.4374 *** | Stationary |

| LEXC | −5.6079 *** | −5.1313 *** | Stationary |

| MPR | −8.1210 *** | −8.1636 *** | Stationary |

| INFGAP | −8.3237 *** | −11.5558 *** | Stationary |

| YGAP | −9.2723 *** | −19.0772 *** | Stationary |

| RGDPG | −9.1062 *** | −16.3350 *** | Stationary |

| Model | Chi-Square Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange Rate Pass-through to consumer prices | 368.8556 | 0.0000 *** |

| Exchange Rate Pass-through to producer prices | 1123.55 | 0.0000 *** |

| Exchange Rate Pass-through to export prices | 9712.544 | 0.0000 *** |

| Exchange Rate Pass-through to import prices | 7954.658 | 0.0000 *** |

| Taylor Rule | 272.5593 | 0.0000 *** |

| Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Consumer Prices | Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Producer Prices | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | |||||

| Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | |

| LEXC | 0.7343 | 0.8404 | 0.7286 | 0.8402 | 0.7302 | 1.4928 | 0.7308 | 1.5289 |

| (0.0047) *** | (0.0013) *** | (0.0060) *** | (0.0000) *** | (0.0033) *** | (0.0049) *** | (0.0065) *** | (0.0000) *** | |

| Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | |||||

| LEXC(-1) | 0.0355 ** | (0.0172) | 0.0271 *** | (0.0129) | 0.1647 * | (0.0844) | 0.2145 * | (0.0802) |

| MPR | −0.0356 *** | (0.0012) | −0.0391 *** | (0.0004) | −0.0879 ** | (0.0121) | −0.0869 ** | (0.0166) |

| MPR(-1) | −0.0227 ** | (0.0382) | −0.0204 * | (0.0651) | −0.0345 ** | (0.0336) | −0.0348 ** | (0.0353) |

| RGDPG | 0.0057 *** | (0.0055) | 0.0058 *** | (0.0015) | 0.0026 *** | (0.0084) | 0.0076 *** | (0.0054) |

| RGDPG(-1) | 0.0114 *** | (0.0030) | 0.0086 ** | (0.0190) | 0.0031 *** | (0.0080) | 0.0091 *** | (0.0043) |

| C | −0.4779 * | (0.0923) | 2.1363 ** | (0.0133) | ||||

| Threshold | 5.008 | 5.0046 *** | (0.0000) | 5.0095 | 5.0088 *** | (0.0000) | ||

| SSR | 1.0804 | 1.0377 | 11.3751 | 11.2473 | ||||

| Regime | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Serial Correlation | 0.2214 | 0.2547 | 0.6058 | 0.229 | ||||

| Heteroscedasticity | 0.1694 | 0.2281 | 0.1968 | 0.235 | ||||

| Normality Test | 0.8913 | 0.484 | 0.8003 | 0.1897 | ||||

| Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Export Prices | Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Import Prices | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | |||||

| Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | |

| LEXC | 0.6319 *** | 1.5722 *** | 0.6319 *** | 1.6059 *** | 0.7716 *** | 1.6500 ** | 0.7696 ** | 1.6490 *** |

| (0.0057) | (0.0085) | (0.0001) | (0.0000) | (0.0091) | (0.0308) | (0.0426) | (0.0000) | |

| Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | |||||

| LEXC(-1) | 0.2720 ** | (0.0471) | 0.8665 * | (0.0642) | 0.1440 * | (0.0665) | 0.2381 * | (0.0518) |

| MPR | −0.0075 ** | (0.0481) | −0.0223 ** | (0.0205) | −0.0180 ** | (0.0135) | −0.0239 * | (0.0734) |

| MPR(-1) | −0.0137 ** | (0.0324) | −0.0446 ** | (0.0176) | −0.0181 ** | (0.0147) | −0.0268 ** | (0.0474) |

| RGDPG | 0.0060 ** | (0.0223) | 0.0167 ** | (0.0127) | 0.0016 * | (0.0719) | 0.0004 * | (0.0926) |

| RGDPG(-1) | 0.0017 ** | (0.0286) | 0.0017 * | (0.0797) | 0.0041 ** | (0.0347) | 0.0028 * | (0.0562) |

| C | 3.1965 *** | (0.0000) | 3.1523 *** | (0.0000) | 1.6324 *** | (0.0058) | 1.6459 *** | (0.0051) |

| Threshold | 5.0072 | 5.0152 *** | (0.0000) | 5.0119 | 5.0214 *** | (0.0000) | ||

| SSR | 1.6853 | 2.85 | 1.3506 | 3.28 | ||||

| Regime | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Serial Correlation | 0.1657 | 0.277 | 0.138 | 0.1267 | ||||

| Heteroscedasticity | 0.334 | 0.6018 | 0.614 | 0.5476 | ||||

| Normality Test | 0.812 | 0.7657 | 0.3681 | 0.6456 | ||||

| Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | |

| LEXC | 3.5474 ** | 5.8211 ** | 1.6465 *** | 5.0711 *** |

| (0.0122) | (0.0149) | (0.0022) | (0.0019) | |

| Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | |||

| INFGAP | 0.0111 * | (0.0729) | 0.2080 ** | (0.0207) |

| YGAP | 0.0250 * | (0.0539) | 0.0868 ** | (0.0171) |

| MPR(-1) | −0.9010 *** | (0.0000) | −0.2835 ** | (0.0272) |

| LEXC(-1) | 3.0036 ** | (0.0232) | 1.1104 ** | (0.0133) |

| C | −1.7929 ** | (0.0272) | −6.8490 ** | (0.0310) |

| Threshold | 4.9853 | 4.9826 | ||

| SSR | 102.3113 | 648.3256 | ||

| Regime | 2 | 2 | ||

| Serial Correlation | 0.8808 | 0.8675 | ||

| Heteroscedasticity | 0.5466 | 0.5414 | ||

| Normality Test | 0.1345s | 0.1389 | ||

| Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Consumer Prices | Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Producer Prices | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | |||||

| Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | |

| LEXC | 0.7143 | 0.8104 | 0.7316 | 0.8392 | 0.7102 | 1.4889 | 0.7334 | 1.5189 |

| (0.0017) *** | (0.0000) *** | (0.0089) *** | (0.0000) *** | (0.0003) *** | (0.0019) *** | (0.0095) *** | (0.0000) *** | |

| Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | |||||

| LEXC(-1) | 0.0351 ** | (0.0171) | 0.0281 *** | (0.0123) | 0.1659 * | (0.0876) | 0.1425 * | (0.0802) |

| MPR | −0.0358 *** | (0.0015) | −0.0341 *** | (0.0007) | −0.0821 ** | (0.0121) | −0.0667 ** | (0.0166) |

| MPR(-1) | −0.0245 ** | (0.0388) | −0.0274 * | (0.0798) | −0.0398 ** | (0.0465) | −0.0398 ** | (0.0328) |

| RGDPG | 0.0012 *** | (0.0078) | 0.0059 *** | (0.0098) | 0.0090 *** | (0.0061) | 0.0093 *** | (0.0094) |

| RGDPG(-1) | 0.0178 *** | (0.0054) | 0.0066 ** | (0.0189) | 0.0059 *** | (0.0066) | 0.0089 *** | (0.0083) |

| C | −0.8779 * | (0.0998) | 2.1999 ** | (0.0133) | ||||

| Threshold | 5.008 | 5.0046 *** | (0.0000) | 5.0095 | 5.0088 *** | (0.0000) | ||

| SSR | 1.1804 | 1.8970 | 11.9886 | 11.7863 | ||||

| Regime | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Serial Correlation | 0.5212 | 0.8747 | 0.9565 | 0.4799 | ||||

| Heteroscedasticity | 0.3664 | 0.8951 | 0.9384 | 0.8697 | ||||

| Normality Test | 0.8983 | 0.6849 | 0.7886 | 0.8686 | ||||

| Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Export Prices | Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Import Prices | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | |||||

| Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | |

| LEXC | 0.6319 *** | 1.5722 *** | 0.6319 *** | 1.6059 *** | 0.7716 *** | 1.6500 ** | 0.7696 ** | 1.6490 *** |

| (0.0057) | (0.0085) | (0.0001) | (0.0000) | (0.0091) | (0.0308) | (0.0426) | (0.0000) | |

| Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | |||||

| LEXC(-1) | 0.2720 ** | (0.0471) | 0.8665 * | (0.0642) | 0.1440 * | (0.0665) | 0.2381 * | (0.0518) |

| MPR | −0.0075 ** | (0.0481) | −0.0223 ** | (0.0205) | −0.0180 ** | (0.0135) | −0.0239 * | (0.0734) |

| MPR(-1) | −0.0137 ** | (0.0324) | −0.0446 ** | (0.0176) | −0.0181 ** | (0.0147) | −0.0268 ** | (0.0474) |

| RGDPG | 0.0060 ** | (0.0223) | 0.0167 ** | (0.0127) | 0.0016 * | (0.0719) | 0.0004 * | (0.0926) |

| RGDPG(-1) | 0.0017 ** | (0.0286) | 0.0017 * | (0.0797) | 0.0041 ** | (0.0347) | 0.0028 * | (0.0562) |

| C | 3.1965 *** | (0.0000) | 3.1523 *** | (0.0000) | 1.6324 *** | (0.0058) | 1.6459 *** | (0.0051) |

| Threshold | 5.0072 | 5.0152 *** | (0.0000) | 5.0119 | 5.0214 *** | (0.0000) | ||

| SSR | 1.6853 | 2.85 | 1.3506 | 3.28 | ||||

| Regime | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Serial Correlation | 0.1657 | 0.277 | 0.138 | 0.1267 | ||||

| Heteroscedasticity | 0.334 | 0.6018 | 0.614 | 0.5476 | ||||

| Normality Test | 0.812 | 0.7657 | 0.3681 | 0.6456 | ||||

| Threshold Regression | Smooth Threshold Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Regime | High Regime | Linear Model | Non-Linear | |

| LEXC | 3.1356 ** | 5.8341 ** | 1.6685 *** | 5.0691 *** |

| (0.0127) | (0.0189) | (0.0013) | (0.0000) | |

| Non-Threshold Regressors | Non-Threshold Regressors | |||

| INFGAP | 0.0111 * | (0.0789) | 0.2011 ** | (0.0209) |

| YGAP | 0.0259 * | (0.0521) | 0.0811 ** | (0.0170) |

| MPR(-1) | −0.9034 *** | (0.0000) | −0.2898 ** | (0.0278) |

| LEXC(-1) | 3.0016 ** | (0.0287) | 1.1159 ** | (0.0135) |

| C | −1.7911 ** | (0.0296) | −6.8477 ** | (0.0313) |

| Threshold | 4.9900 | 4.9823 | ||

| SSR | 102.3134 | 600.3065 | ||

| Regime | 2 | 2 | ||

| Serial Correlation | 0.8006 | 0.9619 | ||

| Heteroscedasticity | 0.6418 | 0.4411 | ||

| Normality Test | 0.1765 | 0.2396 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oyadeyi, O.O.; Oyadeyi, O.A.; Iyoha, F.A. Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Prices in Nigeria—A Threshold Analysis. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2024, 12, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs12040101

Oyadeyi OO, Oyadeyi OA, Iyoha FA. Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Prices in Nigeria—A Threshold Analysis. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2024; 12(4):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs12040101

Chicago/Turabian StyleOyadeyi, Olajide O., Oluwadamilola A. Oyadeyi, and Faith A. Iyoha. 2024. "Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Prices in Nigeria—A Threshold Analysis" International Journal of Financial Studies 12, no. 4: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs12040101

APA StyleOyadeyi, O. O., Oyadeyi, O. A., & Iyoha, F. A. (2024). Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Prices in Nigeria—A Threshold Analysis. International Journal of Financial Studies, 12(4), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs12040101