Abstract

Women entrepreneurs in the Middle Eastern region, particularly in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), face several challenges (e.g., cultural) coupled with the recent transformation of the digital economy. This issue poses a significant challenge for financing the business operations. Thus, this study aims to find the relationship between prior family business exposure, growth intention, motivation, and financial bootstrapping with the mediating role of prior experiences among women entrepreneurs in the UAE. A quantitative survey questionnaire method was used to collect responses from 318 women business owners in different regions of the UAE. The findings of the study suggest that there is a positive relationship between prior family business exposure and financial bootstrapping and growth intention and financial bootstrapping, and prior experience plays a mediating role among all exogenous variables. The study offers a unique perspective on the intersection between prior family business exposure, growth intention, motivation, and financial bootstrapping, highlighting the mediating role of prior experience in a demographical and geographic context (e.g., UAE) that is under-researched regarding financial strategies.

1. Introduction

In recent years, we have witnessed the ascendancy of the digital economy—a profound shift that signifies a move from traditional models centered on physical assets to modern frameworks deeply entrenched in digital technologies (Guo et al., 2023). This transformative wave is more than just a fleeting trend; it is an economic revolution that has birthed new business realms such as e-commerce, fintech, and digital content creation, all while injecting innovation into pre-existing sectors (Tao et al., 2023). Countries like the UAE, the US, the UK, and India stand as testaments to the boundless potential of this digital era. They have not merely adopted digital strategies but have intertwined them into the very fabric of their societal and economic structures (Xun et al., 2020).

The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic has unleashed profound repercussions on global economies, with a substantial impact extending to numerous Middle Eastern countries, including the UAE, which grapples with economic challenges on various fronts. Within this context, Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) have encountered an array of predicaments, including dwindling demand, scarcities of raw materials, the truncation or cancellation of export orders, and a dearth in workforces due to nationwide lockdown measures (Abdelrahman & Ismail, 2022). It is widely acknowledged that MSMEs often lack substantial financial reserves, rendering them particularly susceptible during unforeseen crisis circumstances (Joseph Jerome et al., 2023). The unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 crisis caught businesses off-guard, leaving them ill-prepared to navigate the complexities of operational disruptions, a challenge that is expected to persist over the course of several years (Bartik et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2020, 2021). Across the global landscape, MSMEs form the backbone of economies, offering substantial employment opportunities (Mpi, 2019). Notably, the Middle East has emerged as a hub of digital economic advancement, with MSMEs and women entrepreneurs playing a pivotal role in mitigating poverty levels (Agenda, 2023).

Despite women entrepreneurs making significant strides in various Arab economies, challenging stereotypes, and paving the way for future generations, they still constitute a minority in the region’s business landscape. In the Middle East and North African (MENA) region, less than 5 percent of businesses are led by women, a notable contrast to the global average of 26 percent. Securing funding poses a formidable challenge for women in the region, with a majority opting for informal sources, such as personal savings or family support, rather than pursuing formal financing avenues. Those who do seek investment encounter distinct challenges, as highlighted by a Wamda and TiE Dubai report, which revealed that 66 percent of women founders in MENA believe investors exhibit a reluctance toward backing start-ups led by women. This concern is underscored by the fact that female-only start-ups received less than $50 million in investment during the first nine months of 2022, comprising a mere two percent of the total start-up investment in the region during that period (Monzer, 2023).

As per the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM, 2023) women entrepreneurship report, 25.9% of women (UAE) think that digital tools are not necessary for pursuing entrepreneurship. However, when we analyze the pre-COVID situation, 13% of women had plans to adopt digital technology; this number has increased to 26.9% in post-COVID times, which shows the influence of COVID-19 on adopting digital means. According to Manolova et al. (2020), three major challenges have been reported for women entrepreneurs during the COVID-19 crisis. First, the recession has disproportionately affected the industries where women operate based on the fact that more women are involved in education, hospitals, social services, and a few other sectors compared to men (Elam et al., 2019). Second, women are more likely to run most of the youngest and smallest ventures, which makes them more vulnerable due to the economic downturn caused by the pandemic. Third, having schools closed due to lockdown and elderly members’ lives under threat, they have to indulge more in house chores instead of saving their ventures. Although these challenges exist, solutions related to gender-related threats for women entrepreneurs include cost-cutting through digital means while using financial bootstrapping techniques and gaining access to the opportunities formed during COVID-19 (Manolova et al., 2020).

The digital age has brought many opportunities to female entrepreneurs in the UAE in post-COVID times. Women have been able to expand their customer base beyond borders through various digital platforms, thus giving them access to global markets. The need for big physical infrastructure has been minimized in addition to lowering start-up costs due to the fact that there is no need to keep up heavy infrastructure in such instances when it comes to online trading or marketing. In addition, the financing of MSMEs at all stages of their life is probably the biggest challenge faced by most entrepreneurs (Franco et al., 2020). Entrepreneurs use various sources to fulfill their financial needs throughout the venture’s life. The choices vary depending on the availability of financial sources such as debt, equity, and bootstrapping. There are many sources to support entrepreneurial ventures at the start-up stage, such as financial institutions, government agencies, trade credit, and wealthy individual investors, but the majority of the small ventures are financed by the owner himself or herself. Hence, financial bootstrapping is known as the usage of strategies used by entrepreneurs to increase the value of their resources by integrating different strategies, such as improving cash flow by reducing expenses or mitigating the role of necessities to pay while focusing on increasing the finances internally (Khan et al., 2016; Smith & Blundel, 2014).

The usage of bootstrapping at the initial stages of the venture has been a topic of many studies, but little has been explored in this connection after the take-off stage. The value of bootstrapping has been subject to much debate. Many researchers have supported bootstrap financing for a venture as this neither requires a business plan nor collateral (H. Van Auken, 2003) and gives entrepreneurs a lot of freedom without undue pressure from external investors (Bhide, 1991).

However, digitalization has also become a challenge for women, with a special emphasis on bootstrapping. This is mainly due to the combination of societal, structural, and financial factors in regard to the Middle East, particularly the UAE. Some women entrepreneurs would find it hard to access any of the digital tools or platforms due to limited digital literacy. Moreover, the aforementioned challenges may be compounded culturally in terms of women pursuing a venture that is not technology-driven, or that would require them to go to public digital spaces for fundraising and business purposes (Samara & Terzian, 2021).

The other features that define women entrepreneurs in the Middle East include a preference for a home business or culturally appropriate businesses, reliance on personal or family networks for borrowing, and sectors like those in retail, fashion, or food and beverages (Fitzsimons et al., 2023). These sectors are best positioned for digital platform play, but the women’s inability to have targeted mentorship and a lack of access to professional networks or training on advanced digital strategies limit their opportunities. Therefore, efforts should be directed toward digital and financial literacy among women, inclusion in tech-driven networks, and designing gender-sensitive funding platforms that will speak along regional cultural dynamics.

As far as the research gap is concerned, considering women entrepreneurs from a Middle Eastern country as a sample in the context of this whole framework is presumed to be a unique research attempt, to the best of researchers knowledge. Past research has explored the financial bootstrapping approach through various avenues (Rita, 2019). Neely and Van Auken (2012) emphasized the correlation between the implementation of bootstrapping and the access to short-term and long-term debt for small enterprises. Fatoki (2014) delved into the financial bootstrapping methods adopted by immigrant entrepreneurs. Grichnik et al. (2013) underscored both the precursors and ramifications of bootstrapping. Given these considerations, this study identifies several gaps yet to be addressed. In this context, the influence of family business exposure, motivation, and growth intentions emerge as crucial factors that positively impact the potential for financial bootstrapping in the growing digital era. The objectives of the study are to explore the (i) role of prior family business exposure (PFBE), (ii) growth intentions (GI) in relationship with financial bootstrapping (FB), and (iii) the mediating role of Prior Experience (PE) among independent variables such as PFBE, GI and Motivation (MOT), and FB among women entrepreneurs pursuing digital means in the UAE in post-pandemic times. The rest of the paper will be presented as follows: an extensive literature review followed by hypotheses development. Thereafter, the paper has outlined the research methodology, explained the data analysis, and presented the results. The paper concludes with an in-depth discussion, incorporating future research and limitations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Underpinnings

As far as the theoretical underpinning of the study is concerned, the pecking order theory supports the overall framework of financial bootstrapping (Rita & Nastiti, 2024). According to this theory, micro and small entrepreneurs need financing to start and develop their new ventures in order to be successful. For numerous small business proprietors, securing funds from financial institutions is a crucial aspect of supporting investments and sustaining competitiveness (Armstrong et al., 2013). However, the prerequisites of collateral and extensive documentation often accompanying bank loans render this avenue less appealing for micro and small business owners. An additional insight suggests that beyond internal financing methods, certain proprietors resort to inventive informal financing strategies to raise capital (Beck, 2007; Rita & Nastiti, 2024). The theory suggests a dominant financial order adhered to by businesses, indicating a tendency to prioritize the utilization of internal resources, such as retained earnings, rather than seeking external financing, like bank debts. When external funding becomes necessary, a predilection for debt financing over equity financing emerges. This is particularly relevant due to the constraints surrounding tangible assets available for collateral in bank loan applications; many micro and small enterprises find bootstrap financing methods more accessible for fulfilling their capital requirements. Studies pertaining to the pecking order theory highlight entrepreneurs’ inclination to prioritize internal approaches over external ones for financing (Nkwinika, 2023).

Due to the distinct features of digital firms, this theory can be especially significant in the context of the digital economy (Rita & Nastiti, 2024). The business models of numerous digital ventures, particularly in the areas of software, e-commerce, and fintech, are less reliant on capital and can grow rapidly. Consequently, they rely mostly on internal funding sources like retained earnings in their expansion endeavors (Nassar & Malik, 2022). In doing so, these companies may avoid tapping into external financing that could increase investor scrutiny and dilute power over decision-making processes by reinvesting profits into product development, marketing, and expansion. Furthermore, in spite of the fact that it is often associated with start-ups and can be seen as debt financing for digital companies, digital companies are still on the safe side when it comes to this kind of financial lever. The volatility of this sector based on rapid changes in technology and market conditions makes debt financing costlier for such firms. Due to low earnings, these companies are careful not to engage in extensive borrowing because the high cost of debts does not allow them. Therefore, most of these companies follow the pecking order theory, which requires that they use internal funds first and, afterward, borrow with caution before finally considering selling equity if the need arises.

2.2. Financial Bootstrapping

One of the earliest authors who considered bootstrapping as a less conventional financing technique was Bhide (1991), who reported its potential to support small ventures at various stages of a venture. According to the research findings, entrepreneurs do not rely much on institutional financing due to its complex procedure. Rather, they prefer financial bootstrapping because of its simplicity and less costly nature (Fitzsimons et al., 2023; Malmström & Hällerstrand, 2023). Another study by Kargwell (2012) reported that women who used microfinancing were normally between the age group of 30–40 years, were married, and had less/no formal education. Less than half of the women borrowers were facilitated by microfinance institutions to start new business ventures, whereas the majority of the women used their own funds to support their already established ventures.

V. Van Auken (2005) has specified twenty-eight bootstrapping techniques grouped in five dimensions: sharing resources, delaying payments, private-owner financing, minimizing investments, and minimizing accounts receivables. Another study conducted on small enterprises by Al Issa (2021) identified four dimensions of financial bootstrapping: (i) customer-oriented, (ii) delaying-payment-related, (iii) owner-related, and (iv) the joint-utilization of resources. In this context, customer-related means that advance payments from customers are encouraged. On the other hand, delaying payments reflects negotiation with the suppliers for extended periods of time against accounts payable. Similarly, owner-related bootstrapping highlights using personal funds or taking loans from family or friends; and in the end, joint-utilization means the agreements with other micro/small businesses for sharing the physical and human resources. This study has adopted Al Issa’s approach to financial bootstrapping because of its relevance to this study.

Apart from these financial bootstrapping strategies, there are several other ways female entrepreneurs can adopt self-sufficiency strategies. One of them is equity crowdfunding. It permits bringing a fund raised from a large pool of small individual investors through an online platform to entrepreneurs. Giving equity in return for investment enables female entrepreneurs to avoid traditional financing barriers, including gender bias or a lack of collateral (Rutherford et al., 2022). Such online platforms include Kickstarter and Indiegogo, both of which have made this method highly accessible, especially for general businesses. However, this means multi-stakeholder management for entrepreneurs and requires transparency as well as regulatory compliance. Thus, it may not be practical for everyone, but it is mostly suitable for ventures focusing on sectors like technology, fashion, or artisanal products. Similarly, digital finance is an important tool for economic development (Liao & Du, 2024).

Crowdsourcing is yet another powerful strategy. It encourages collective cooperation to cut costs for the entrepreneur. Below are some avenues where women entrepreneurs can use sites like ‘Upwork’ to provide cheaper services like graphic designing, website development, or market research (Mariani & Chatterjee, 2023). This likewise creates customer engagement in product development or fine-tuning, making it less financially based but more loyal. Similarly, another cost-saving measure for women entrepreneurs is bartering services within collaborative economies. When they share their expertise or a resource with another entrepreneur, they create a cash-free relationship without needing to transact money. As such, women form a supportive entrepreneurial environment. Pre-sales or subscription models are workable bootstrapping mechanisms for entrepreneurs to collect revenue upfront for their products or services by making them available for sale in advance via platforms such as ‘Shopify’. This technique is widely used in creative fields because it allows female entrepreneurs to raise initial funding from their customer base. These methods are highly innovative but rely on excellent marketing, high levels of computer literacy, and good interpersonal skills to work in very competitive environments.

All the aforementioned techniques show the importance of the expansion of digital technologies. The competition is now digital, letting female entrepreneurs go beyond national borders and adopt data-driven methods in their engagements with customers. For instance, the She Trades ME initiative has aided women in the UAE in exporting products through online marketplaces (ITC, 2015). It emphasizes, however, how the digital economy continues to bring down entry barriers and even the playing field, notwithstanding the digital skills shortage and the technology resource constraints that remain sore points.

The financial self-sufficiency of women entrepreneurs varies greatly across regions due to cultural, policy, and social factors. In the United Arab Emirates, for instance, government empowerment initiatives such as the National Strategy for Empowerment of Emirati Women and various financing programs promote entrepreneurship, specifically by aligning them with digital and green economies. In addition to supportive policies, women entrepreneurs in the UAE have several channels that include raising equity through a crowdfunding platform and pre-sales, but they still face challenges due to cultural norms that incline toward gender bias at times (Heath, 2021). The Nordics, to some extent, are comparable to the entrepreneurial ecosystem: excellent access to public funding (Laugesen et al., 2021), while South Asia depends heavily on informal financing (Khalil et al., 2020). Community lending and Mobile money platforms are prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa, whereas venture capital dominates in the West, but gender disparity remains.

Surprisingly, the modern and digitally oriented policies of the UAE are propelling it forward in many areas of the globe in terms of developing female entrepreneurship. The further development of mentorship and venture funding, enormously expanding upon any offerings now available, is necessary to bring the ecosystem anywhere close to those of Western economies or the highly inclusive Nordic nations. It is, however, the same strength and resilience that unites all female entrepreneurs; the kind of financing strategies they adopt and the success they achieve depend entirely on the cultural attitudes prevalent in their regions, the funding ecosystems, and institutional support.

2.3. Prior Family Business Exposure

Several studies within the realm of family businesses have indicated that exposure to family business dynamics and an early introduction to entrepreneurship can have a positive impact on an individual’s subsequent entrepreneurial endeavors (Mahmoud et al., 2023; Zaman et al., 2021; Katz, 1992). Entrepreneurs often draw inspiration from family members who have established themselves as entrepreneurs, motivating them to initiate their ventures. Family, particularly that of entrepreneurs, is a close-knit relationship, particularly children who observe their parents and learn skills that are crucial for pursuing entrepreneurship (Zaman et al., 2021). In this study, the definition of prior family business exposure aligns with description from Carr and Sequeira (2007), indicating an individual’s familial connection to a business owner and their involvement in the family enterprise.

One of the leading studies intended to explore the effect of PFBE on women entrepreneurs was conducted by Roomi and Parrott (2008). A significant finding was that almost 70% of women entrepreneurs had their fathers, brothers, and husbands in the business field who supported and encouraged them to take on the challenges to start new ventures. This prior family background gave them an awareness of using financial bootstrapping to fulfill their funding requirements. A study conducted by Perveen (2019) focused mainly on women entrepreneurs and reported that the majority of women entrepreneurs had one or both of their parents as successful entrepreneurs who helped them raise capital through bootstrapping techniques. As per Welsh et al. (2018), those women entrepreneurs who had a family background in entrepreneurship performed better. According to Edelman et al. (2020), women entrepreneurs rely on their strong family ties for support and creative methods. In another research endeavor, Hisrich and Brush (1983) conducted interviews with 468 entrepreneurs, revealing that among the women entrepreneurs surveyed, a significant proportion indicated having parents and/or spouses who were self-employed.

In addition, exposure to family businesses results in effective decision-making and resource management, which are crucial components of bootstrapping (Cruz et al., 2021). Such entrepreneurs develop internal strategies to maximize the output with minimum resources. Within the digital economy, characterized by inexpensive business solutions facilitated by digital technology and platforms, these entrepreneurs might, as such, be particularly adept at maximizing the utilization of such technologies to support their start-ups. Specifically, they may use online marketplaces instead of a traditional store, social media for promotions, or even cloud-based services in order to save up on overlying costs, all of which conform to bootstrapping fundamentals (Olanrewaju et al., 2020). Looking at past studies leads to the first hypothesis.

H1.

There is a positive relationship between PFBE and FB.

2.4. Growth Intention

Growth intention pertains to the ambition for business expansion, encapsulating the intention to nurture growth. Within Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior, attitudes play a significant role, not just in shaping an entrepreneur’s choice to expand their business but also in dictating their commitment to maintaining growth and its scale over time. This concept of gradual, unfolding growth is widely explored within the literature. This construct draws from the insights of McNeill’s research (McNeill, 2015), revealing that women entrepreneurs’ growth intentions are shaped by factors such as excitement, the availability of time and growth potential, family support for expansion, and the confidence to fully realize the venture’s growth potential.

Numerous management literature have reported intention being the major driving force towards entrepreneurial growth aspirations. It has been the topic of various research studies (Amit et al., 1996; Gundry & Welsch, 2001; Wiklund et al., 2003). A choice by women entrepreneurs can be the central principle behind their growth, which can eventually lead to the better creation of financial methods (Huq et al., 2020). According to Gupta (2019), GI has a significant role in enhancing FB. A similar study reported a significant relationship between GI and FB (Pret & Cogan, 2019). A research study (Cliff, 1998) pointed out the difference among entrepreneurs in terms of their growth intentions, whereas another study focused on the need for wealth achievement and willingness to grow (Amit et al., 1996). Entrepreneurial researchers focus on understanding and predicting intentions and growth aspirations. The availability of financial resources can be challenging for entrepreneurs in order to pursue their growth intentions. Brush et al. (2004) concluded that GI plays a vital role in the usage of FB.

Growth-oriented entrepreneurs typically seek to rapidly expand their businesses while minimizing cash-on-hand dependency. Financial bootstrapping, which involves creatively using internal resources and low-cost methods to finance growth, aligns well with this objective (Coad et al., 2023). In order to achieve this, digital platforms such as social media marketing, e-commerce platforms, and cloud-based services can be used (Leitner & Güldenberg, 2021). Thus, it is likely that entrepreneurs who aim for major growth are more inclined to use bootstrapping methods in order to exploit these digital tools, which enable them to grow rapidly but also prevent them from losing control and incurring high financial risks. This leads to the second hypothesis.

H2.

There is a positive relationship between GI and FB.

2.5. Motivation

Regarding motivation, the definition employed is derived from Stefanovic et al.’s (2010) investigation, encompassing the fundamental factors that drive entrepreneurial enthusiasm and effectiveness. Motivation is a necessary factor for both starting up a new venture and running it smoothly on the path to success (Robertson et al., 2003). According to Colombo and Marques (2020), there is a significant relationship between motivation and prior experience. There are several factors that motivate entrepreneurs, with social factors being one of the many. There is sufficient empirical evidence to predict the predominant motives for the usage of bootstrapping in the literature—not enough capital, managing finances internally, and risk reduction (Fitzsimons, 2018). It has also been reported that entrepreneurs generally are reluctant to renounce control of their ventures. This indicates a desire to have more efficient resource management. Previous studies also identified that most women entrepreneurs look for independence, autonomy, flexibility in decision-making, and family security (Zellner et al., 1994).

Many studies have explored the relationship between the motivating factors of women entrepreneurs and the way they resolve financial challenges (Okafor & Amalu, 2012). As a result, women are motivated towards entrepreneurship because it offers them independence and a sense of achievement. It also facilitates their utilization of their fullest potential. A study conducted by Hisrich and Öztürk (1999) found that women entrepreneurs were more educated and had prior work experience before they were drawn towards entrepreneurship. There have been clearly defined sets of motivations that support women in making their decision to become entrepreneurs. Researchers agreed that highly motivated entrepreneurs are usually those who have prior managerial experience (Wiklund et al., 2003). Previous start-up experience can also provide a basis for motivation to entrepreneurs as it gives them expertise and knowledge for identifying new opportunities as well as running their businesses more efficiently (Davidsson & Honig, 2003).

Entrepreneurs who are intrinsically motivated, motivated by their passions, and have prior experience, personal ambitions, or commitment to a vision usually have great resourcefulness and determination in addressing issues of limited finances (Newman et al., 2022). In line with their intent to be in charge of their own businesses and attain their objectives, such entrepreneurs embrace financial bootstrapping that minimizes dependence on external financing. A digital economy in this context offers multiple opportunities for motivated entrepreneurs to use online platforms to manage their finances carefully (Chatterjee & Kar, 2022). The aforementioned discussion leads to the third hypothesis;

H3.

There is a positive relationship between MOT and PE.

2.6. Prior Experience

Prior experience also plays a crucial role in determining financial bootstrapping among women entrepreneurs. The definition for this variable was taken from a study conducted by Quan (2012), who considered job/management experience, educational background, and previous venture founding experience to ascertain the prior experience of an entrepreneur. A number of researchers have stressed that experienced entrepreneurs acquire valuable knowledge through their relations. This knowledge is beneficial for them in taking advantage of entrepreneurial prospects (Tarling et al., 2016). According to Beriso (2021), the educational level of the entrepreneur herself, the parent’s educational level, and prior business experience have a positive influence on the women entrepreneurs’ incomes. Family exposure in entrepreneurial activities involves not just parents but also other family members and relatives. Other family members of the same generation (i.e., siblings and relatives) could provide positive examples and practical experience (Lentz & Laband, 1990). PFBE influences the entrepreneur’s aspirations by supporting and encouraging them. As family plays a helpful role in the entrepreneurial process, it has been generally observed that the family background is a constant role model for entrepreneurs (Farrukh et al., 2017).

PFBE is an important element in enriching the experience of entrepreneurs, particularly in countries where support is much needed for running businesses due to limited access to financial resources. Researchers studied the impact of PFBE in developing individuals’ experiences that facilitate the identification and location of scarce resources (Uzzi, 1999). Likewise, these contacts and experience facilitate the exploitation of opportunities and better access to scarce financing resources. De Carolis and Saparito (2006) synthesize two major effects of PE and PFBE that are relevant to entrepreneurs: information and influence. Johannisson (1988) establishes that it is important for the entrepreneur to possess a diverse personal network and information to acquire necessary resources that are acquired from PE or the family network (Jiang et al., 2018). The aforementioned discussion leads to the fourth hypothesis;

H4.

There is a positive relationship between PFBE and PE.

The actual growth of a small business relies on the entrepreneur’s ability to manage growth (Sexton & Bowman-Upton, 1991). This involves the capacity to make internal adjustments with the increasing size of the business, as well as the willingness to continuously exploit growth opportunities (Slevin & Covin, 1997). The literature suggests that PE provides expertise in strategic decision-making since GI requires careful planning for managing environmental changes and the raising of additional resources. Business owners with PE are in a better position to make correct decisions and, hence, achieve the growth objectives of their ventures. This study presents three types of PE: educational background, job/management experience, and previous venture founding experience. Several studies have supported the notion that prior knowledge and work experience greatly support entrepreneurs in their growth intentions (Basit et al., 2020; Klepper, 2001). As per Basit et al. (2020), women’s entrepreneurial success is largely dependent on work experiences. Moreover, PE is the result of inputs through education and experience, which supports the entrepreneur’s growth initiatives (Snell & Dean, 1992). Educational knowledge is usually general for people and might not provide instant support to one’s entrepreneurial behavior, but it supports the entrepreneurs’ future growth-related decisions. More recently, some researchers have reported that education does have a positive impact on entrepreneurial growth intention (Capelleras & Hoxha, 2010). The study reported that business owners with better education and experience showed the tenacity to understand the environmental factors better, suggesting that there could be an underlying relationship between experience, knowledge, and growth intention (Kautonen et al., 2014). Experienced individuals have been found to run high-growth small businesses compared to less-experienced individuals (Sapienza & Grimm, 1997).

As per Baum et al. (2023), entrepreneurs derive crucial information, capabilities, and connections from prior experiences that are essential for spotting and seizing expansion chances. They possess an advantage over less-experienced individuals due to their ability to exploit the intricacies of a digital economy through discovering large-scale operational models for businesses using available digital channels coupled with better targeting of manifold customers in diverse areas. Therefore, they have high aims regarding expansion, which they are determinedly chasing (Autio et al., 2021). Moreover, in the context of the digital economy, prior experience may be extremely valuable for understanding market trends, consumer behavior, and technological advancements that play a key role in driving growth. The aforementioned discussion leads to the fifth hypothesis;

H5.

There is a positive relationship between GI and PE.

Bootstrapping is a creative way to arrange capital without using the conventional bank financing option. The major focus of bootstrapping methods is on internal financing through the smart management of businesses’ own resources and better credit management. Reynolds and White (1997) conducted a study in two states in the USA and found that PE in both related and unrelated businesses increased the chances for bootstrapping usage. A study conducted by Brush et al. (2004) emphasized that college education and industry experience supported exploring bootstrapping methods to raise financial capital. Scholars contend that entrepreneurs possessing managerial backgrounds and those who have pursued advanced academic education or specialized business training tend to be more actively involved in the practice of bootstrapping (Grichnik et al., 2013). Another study points out that individuals with relevant business and entrepreneurial education have more systematic thinking and are in a better position to explore financing opportunities (Quan, 2012). Carter et al. (2003) conducted multiple studies and found a positive relationship between the education of entrepreneurs and their usage of bootstrap financing. Their findings suggest that entrepreneurs with higher levels of education are more inclined to explore and adopt bootstrap financing methods. It has been evident that individuals with business and finance education are better aware of the financing alternatives for their ventures. The aforementioned discussion leads to the sixth hypothesis;

H6.

There is a positive relationship between FB and PE.

H7.

PE mediates the relationship among PFBE, MOT, GI, and FB.

H7a.

PE mediates the relationship between PFBE and FB.

H7b.

PE mediates the relationship between MOT and FB.

H7c.

PE mediates the relationship between GI and FB.

3. Results

Data analysis was performed through a descriptive and inferential type of analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated using SPSS 22, and hypotheses testing was performed using a covariance-based AMOS.

Table 1 shows the sample composition with marital status, venture age, and number of employees. As can be seen, most of the businesses were composed of health and safety products. Also, the number of employees was less than 35, so they fit in the micro and small enterprises segment.

Table 1.

Sample composition.

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The purpose of a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) is to reduce the factors that do not properly load on the variables. CFA is used to identify the factor loadings through standardized regression weights. Items having more than 0.5 factor loadings have been retained, whereas factor loadings less than 0.5 are removed, as highlighted in Table 2 (Hair et al., 2006). Items deleted in CFA are MOT 6, MOT 9, FB1, and FB3 to FB12. The fundamental aim of using the measurement model is to check whether the adapted tool is valid and reliable in the specific settings of the UAE.

Table 2.

Composite reliability and convergent validity.

To assess the reliability of all the elements, composite reliability was employed. As per the established criteria, items with values falling between 0.7 and 1.0 are deemed reliable (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Table 3 demonstrates that all the values fall within the targeted range, ranging from 0.885 to 0.949. According to Cortina (1993), if composite reliability is above 0.70, then it is acceptable. If it is 0.80 or more, then it is much better. In our case, all indices have composite reliability values close to or above 0.90. This suggests that all the items for each of the variables are internally consistent and further suggests that there is strong reliability across the items of the indices we have selected, i.e., PFBE (0.918), PE (0.896), MOT (0.885), GI (0.949), and FB (0.911).

Table 3.

Path coefficients.

Regarding convergent validity, it needs to satisfy three essential benchmarks: the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite Reliability, and Factor Loadings. Primarily, the AVE should exceed 0.50, and in this instance, the values are 0.699, 0.685, 0.530, 0.729, and 0.539. Subsequently, the composite reliability should surpass the 0.70 threshold, which is the case, as evidenced in Table 2. Furthermore, factor loadings must be higher than 0.50, confirming the fulfillment of convergent validity prerequisites (Hair et al., 2006).

Subsequent to constructing the measurement model, the researchers proceeded to formulate the structural model. The distinction between the measurement model and the structural model lies in their respective purposes. The measurement model primarily serves to assess the instrument’s reliability and validity, whereas the structural model is designed to examine the hypothesized relationships by evaluating path coefficients. First, fit indices have been checked and verified in order to run the structural model. The following indices have been used i.e., the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and Normed Fit Index (NFI). As required in the model, values should exceed 0.90; in this case, the values are 0.915, 0.922, 0.933, and 0.915, respectively. Moreover, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) threshold value should not exceed 0.080, and in this case, it is 0.062 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). It shows that the model is a good fit to run and test further relationships.

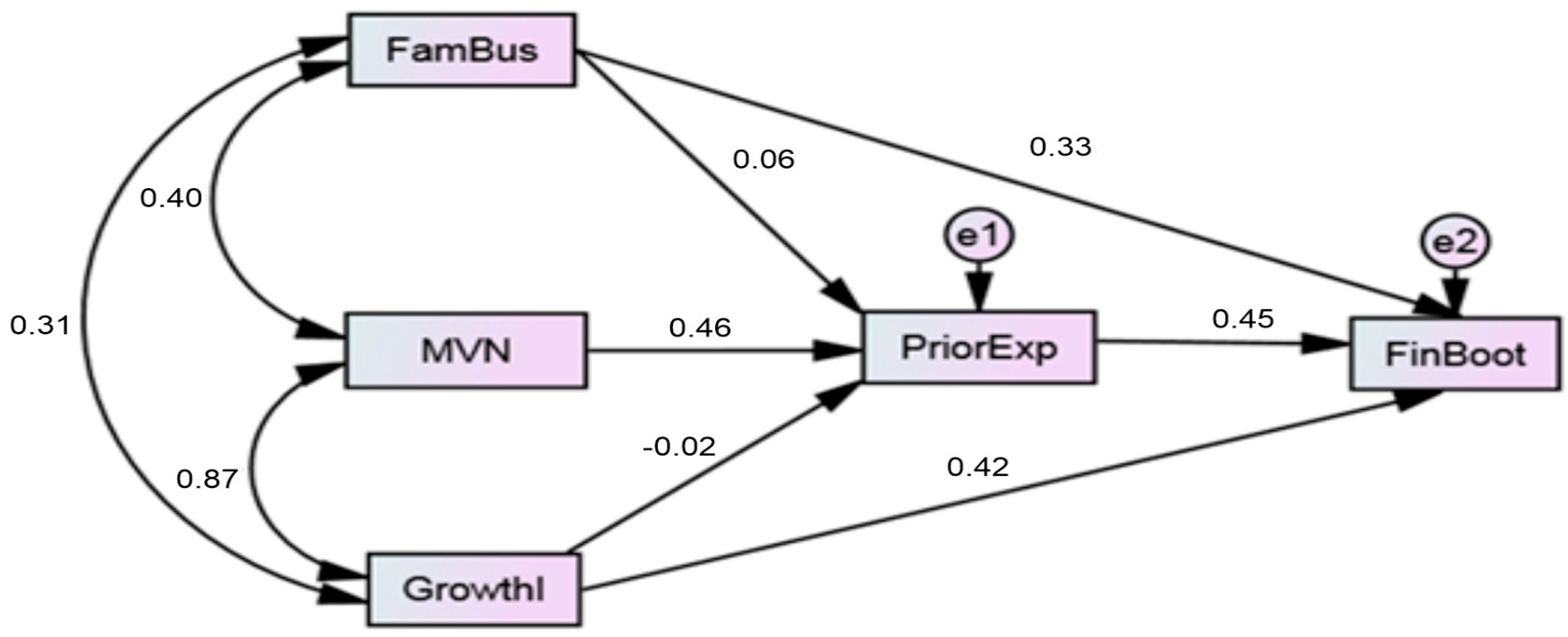

As per Table 3, the relationship between PFBE and FB is found to be positive and significant, with a path coefficient of 0.33, which leads to the acceptance of the first hypothesis. Moreover, as far as the relationship between GI and FB is concerned, it is found to be positive and significant as well, with a path coefficient of 0.42, which leads to the acceptance of the second hypothesis. As far as relationships between PFBE and GI with PE are concerned, they proved to be statistically insignificant. However, the relationship between motivation and PE was found to be statistically significant, with a path coefficient of 0.46. Similar results were found between PE and PFBE at 0.45, leading towards acceptance of the sixth hypothesis (see Figure 1). In addition, as far as the mediatory role of PE is concerned, mediation has been proved in all three paths, i.e., PFBE →PE → FB, MOT → PE → FB, and GI → PE → FB, with indirect effects of 0.099, 0.103, and 0.087, respectively. The Section 5 discusses the results.

Figure 1.

Path Structural Model.

4. Materials and Methods

This research is a quantitative study and primarily subjective in approach as it seeks to understand the usage of bootstrapping methods by women entrepreneurs in the UAE. This study used a questionnaire/survey technique to understand the factors affecting the usage of bootstrapping methods by women entrepreneurs to fulfill their financing needs to support their ventures’ financial requirements. As the study investigates the financing techniques used by the women segment of small ventures from the UAE, where most of them are operating in an informal sector, the respondents did not feel very comfortable sharing their personal as well as venture information; thus, access to such information was challenging. All the women entrepreneurs were associated with e-commerce boutiques.

As most of the respondents were from the informal sector and preferred not to list their ventures formally, therefore, a non-probability sampling technique was used. A combination of convenience and snowball sampling techniques was used, whereas the sample was not industry-specific. Information about women entrepreneurs was collected from various sources in the UAE, such as the Department of Economic Development (DED), chambers of commerce, and the Business Women Council. The survey population consisted of women entrepreneurs who were navigating growth challenges and addressing them by utilizing bootstrapping methods through digital tools and platforms.

Data were collected during the time period of March 2022 to May 2022. A sample size of 318 women entrepreneurs was selected for this study. A sampling frame included all the female entrepreneurs from the field. According to Hair et al. (2006), the general rule is to have a minimum of 5 observations per item (5:1). As the total items were 43, it made a minimum sample of 215. However, questionnaires were distributed to 380 participants for better generalizability. A total of 318 were returned that were considered valid, with a response rate of 83.7%. For the survey, only micro and small enterprises were included. The sample was further divided into various segments of the industry, such as health and safety, cooking/making, education and services, and software/IT-related ventures.

The survey questionnaire items utilized in this study were drawn from earlier research studies, and necessary adjustments were implemented to ensure their appropriateness within the specific context of the UAE. Since this paper aims at gathering information from female business owners, data collection was performed through a survey questionnaire. The survey questionnaire’s validity was evaluated by nine subject matter specialists. Five of them operated as women entrepreneurs and had a good knowledge of financial bootstrap methodologies. The remaining four were academicians in the same field. These experts were asked to study the questions closely and comment on their lucidity as well as ambiguity. In the end, they said that it was easy for anyone to read the questions with understanding. The study analyzed PFBE (Carr & Sequeira, 2007) with three items, with the sample item ‘Does a parent currently own or have they owned a business?’; Motivation (Stefanovic et al., 2010) had nine items, with the sample item ‘To increase my household income’; GI (McNeill, 2015) had seven items, with the sample item ‘I want to grow my business to its full potential’; PE (Quan, 2012) had three items, with the sample item ‘Please indicate the experience (years) of starting or developing a venture before starting this business’; FB had twenty-one items adapted from Winborg and Landström (2001), with the sample item ‘Buy used digital tools or software licenses instead of new ones’.

The issue of common method bias is quite common in such studies. Thus, to address this issue, researchers used Herman’s single factor test (HSF) to determine if a single component was responsible for most of the changes seen in this test. HSF extraction through a principal component analysis in this paper confirmed a maximum extracted variance of 33.4%, confirmed by one factor that was below 50% of the cut-off point, thus demonstrating the absence of the CMB (Huang, 2023). In addition, variance inflation factor (VIF) findings demonstrated that each measurement item complied with Ma and Zhang’s (2023) suggestion (VIF < 3.3). Thus, prior justifications have shown that our dataset results did not demonstrate any observable issues associated with CMB.

Since the data were collected from women entrepreneurs, their confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the study. In addition, informed consent was taken in advance to follow the ethical procedures.

5. Discussion

A number of studies have reported in the past that the nature of challenges faced by women entrepreneurs is considerably different from those of male entrepreneurs (Elam et al., 2019; McManus, 2017). These differences are also prominent when we compare the developed economies with the developing ones. Some of the reasons behind these differences are socio-cultural and religious norms, government support, literacy rates, financing options available for entrepreneurs (Elam et al., 2019), and less encouragement for women entrepreneurs in the UAE. The findings of this study have contributed to better understanding the usage of bootstrapping techniques by women entrepreneurs in the UAE. Although challenges for women entrepreneurs might be different from those for males, governments throughout the world do not take this factor into account (Al Issa, 2021).

In the context of this study, women entrepreneurs can take advantage of technology to minimize costs, streamline operations, and enhance productivity, which is important for bootstrapping methods. In addition, digital platforms also make non-traditional funding options more accessible, which lessens the need for traditional bank loans, which can be challenging to obtain. Digital tools enable entrepreneurs to scale their activities up or down in response to changing market conditions, thereby promoting efficient and adaptive financial resource management.

The primary data for this study were collected for hypothesis testing, and the results of the data stated that the relationship between PFBE and FB among women entrepreneurs was positively significant. This clearly shows that women entrepreneurs involved in their family business before starting their ventures have sufficient knowledge of financing options and their effectiveness for business growth. In times post-COVID-19, by using digital means, this relationship remains significant despite several economic challenges, as PFBE helped women entrepreneurs use FB techniques effectively. A similar relationship was found in the study conducted in Pakistan (Khalil et al., 2020). A similar positively significant relationship was found between the GI and FB among women entrepreneurs. This shows that women entrepreneurs feel positive about adopting a variety of financial bootstrapping techniques, including digital means if they have the intention to grow. Intentions play a crucial role in times of crisis and help them to grow. This encourages them to look into alternate financing options through FB (Pret & Cogan, 2019), even in times of pandemics. This is not only true for Middle Eastern countries since a similar study was conducted in the USA, where the same findings were observed in the context of growth positioning (Brush et al., 2006). Two hypotheses were rejected as having an insignificant relationship between PFBE and PE and between GI and PE. It could be because although PFBE and GI are critical for PE, it has been observed that there are many women entrepreneurs who, despite having PFBE and GI, could not significantly be affected by PE (Muravyev et al., 2009). A direct relationship was observed between motivation and PE in the study, which shows that women entrepreneurs can feel motivated by having prior experience in entrepreneurship. Also, a moderate positive relationship was observed between PE and FB, which shows that women in the UAE work well with FB techniques when having prior experience. It has also been observed in post-pandemic times that women with PE performed better while raising capital through FB to finance both new and existing micro and small ventures.

Women entrepreneurs, especially in the digital economy, face specific challenges compared to their male counterparts. These challenges include limited societal biases, access to capital, and structural constraints that, at times, push them to depend on more innovative and flexible financial methods. For example, while both women and men may engage in FB, women are often more dependent on informal and relationship-based resources, such as borrowing from personal networks or delaying salaries, due to systemic barriers in accessing formal financial systems and venture capital funding.

In this study, specific bootstrapping practices such as coordinating bulk digital purchases with other businesses, engaging in barter of digital services, and hiring gig workers for shorter-term digital projects highlight the adaptive strategies that women entrepreneurs use to address these challenges. In addition, activities such as collaborating with digital innovation hubs, utilizing innovation subsidies, and leveraging personal credit for online subscriptions demonstrate a resourcefulness that may be more pronounced among women, given their limited access to large-scale funding avenues.

Men, on the other hand, tend to have relatively easier access to formal financial systems and may not face the same pressures to rely on informal or relationship-based bootstrapping techniques. This systemic difference in access and opportunity underscores the need to explore and support the distinct financial behaviors of women entrepreneurs in the digital economy.

FB strategies do come with limitations that constrain the capacity of businesses to grow. Such limitations may include the scale at which a source of funding is provided, based on the fact that bootstrapping or using informal channels such as personal savings or family loans does not usually provide a significant amount of capital to scale operations, acquire advanced technology, or support entry into already competitive markets. This also restricts the ability to seize growth opportunities or be responsive to market fluctuating demands (Samara & Terzian, 2021).

These strategies slow down development as well. Congested cash flows tend to compel business persons to focus on immediate survival in terms of longer terms and, therefore, innovations or advancements, which could result in delays in various milestones like the launch of products in the market. Such limitations can also come with factors such as limited access to networks or even outside funding sources, forcing complications for women entrepreneurs on top of what men may face as they attempt to scale their business ventures.

In the case of theoretical contributions of the study, pecking order theory contributes in a way to understanding the effective usage of financial bootstrapping methods. The theory postulates a universal sequence for business financing decisions, elucidating that companies tend to prioritize the utilization of internal funds as opposed to seeking external bank financing, and this theory makes it easier for women entrepreneurs to understand the financial health of the start-ups.

In a nutshell, women entrepreneurs in the UAE and around the world can overcome financial obstacles and create self-sustaining, sustainable businesses by utilizing the digital economy. This strategy is consistent with the study’s findings, which show that the use of digital tools in conjunction with growth purposes and prior exposure to family businesses can support financial bootstrapping and entrepreneurial success.

5.1. Research Implications

Financial institutions play a vital role in the growth of any economy, as businesses of all sizes and magnitudes turn to financial institutions not only for their capital requirements but also to obtain professional and financial guidance at various stages of their business ventures. Micro and small businesses, especially women entrepreneurs, face major challenges in the Middle East when they turn to financial institutions for their capital requirements. In such a scenario, managers of MSMEs should focus on developing relatively easy and new bootstrapping methods to effectively tackle the challenges. In the post-pandemic world, women entrepreneurs have taken such challenges as an opportunity to operationalize new start-ups in the wake of the pandemic with the help of the government and explored relatively easy bootstrapping methods. This emerging trend has led to the shaping up of new business horizons and domains all over the Middle East in post-COVID times. However, the trends are changing, with increasing success stories of small businesses by women entrepreneurs in the Middle East and particularly the UAE, owing to several individual and cultural reasons, particularly in the digital domain of businesses.

It is important for policymakers and financial institutions to comprehend the contextual factors while developing policies and making decisions. Steps should be taken to support women entrepreneurs and encourage them to join the mainstream documented economy. This can ensure a higher contribution to regional development. The government should also support such ventures in times of crisis, as MSMEs face limitations of financial resources that may lead to business failure. Therefore, it is suggested that such policies and supportive decisions should be made by the government to ensure sustainable operations of MSMEs.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

The findings of this study have significant theoretical implications. This study extends the use of the pecking order theory, which states that firms prioritize the use of internal financing over external financing due to the costs as well as asymmetries linked with external financing. Focusing on women entrepreneurs, the research shows that they rank personal savings, reinvested profits, and assistance from relatives among their main sources of capital—a factor that conforms with the pecking order theory’s structure of dominance in terms of finance preferences.

Moreover, it highlights how women entrepreneurs creatively use social capital and community resources to reduce their dependence on outside finance and equity, thus lowering financial risks and ensuring that they retain control over their businesses. These gender-specific insights enhance the pecking order theory by taking into consideration the peculiar financial patterns as well as challenges encountered by female entrepreneurs. The paper also points out that digital tools are very important in promoting access to unconventional sources of funds, thereby implying that there is a need to review the pecking order theory so as to keep pace with changes in technology within entrepreneurship sector finance. Therefore, these investigations not only support the fundamentals of pecking order theory but also widen its scope through gendered and technological lenses.

5.3. Limitations

This study faced some limitations. One of the limitations has been to gain the willingness of the respondents to participate in the study. As the sample consisted of women entrepreneurs managing micro and small businesses, they were mostly in an undocumented economic sector. These women entrepreneurs did not show much willingness to participate in research studies that required them to share their personal and business data with external stakeholders. Another limitation has been the knowledge of the participating women entrepreneurs. Since bootstrapping has been a fairly new concept for the UAE’s women entrepreneurs, and due to less emphasis on technicalities in the Middle East region, it has been difficult to provide a clear understanding of bootstrapping and various methods of doing it to the participants. Moreover, as a snowball sampling technique was opted for, it has a generic drawback. As suggested by many researchers, this approach can yield partial outcomes as individuals often tend to recommend those who share similar attributes, influenced by their social associations. Lastly, although authors have tried to compare the differences between men and women in using FB strategies in the digital realm, the methodological differences in the studies limit the generalizability of the findings and make the results less meaningful.

5.4. Future Directions

Future studies can opt for a longitudinal research design, owing to the importance of data collection at multiple times, to gauge the pattern of financial bootstrapping using digital means. In addition, future studies should use probability sampling techniques for better external validity of the findings. Moreover, future studies can opt for cross-cultural comparisons. Financial bootstrapping practices could be better comprehended through comparative studies that are conjunctionally performed in many different countries and cultural contexts. This would help in finding out common strategies that apply irrespective of location as well as specialized ones limited to specific areas, thus leading to a clearer perspective of financial bootstrapping. In addition, this study is focused on the quantitative side only, so future studies can use mixed-methods research for a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study. Moreover, scholars may conduct a similar survey among male entrepreneurs as well, which will result in a better comparison between male and female entrepreneurs. Last, multi-group analysis can be performed in order to explain which financial bootstrapping method is more common group-wise.

Financial Bootstrapping Items:

- Buy used digital tools or software licenses instead of new ones

- Borrow digital resources from other businesses for shorter periods

- Hire freelancers or gig workers for shorter-term projects

- Coordinate bulk digital purchases with other businesses

- Subscribe to SaaS (Software as a Service) instead of buying outright

- Engage in barter of digital services

- Offer customers discounts for early digital payments

- Buy digital inventory on consignment

- Seek favorable terms from digital service providers

- Deliberately delay payment to digital suppliers

- Withhold manager’s salary temporarily in tough periods

- Use a manager’s private credit card for online subscriptions

- Obtain capital via freelance assignments by managers in other digital ventures

- Request payment in advance for digital services

- Raise capital from online factoring companies

- Obtain loans from personal networks for digital ventures

- Delay tax payments (within legal allowances)

- Seek digital subsidies from local government

- Utilize labor market incentives for digital hiring

- Apply for innovation subsidies

- Collaborate with digital innovation hubs start-ups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. methodology, S.A.; software, S.A.; validation, S.A.R.; formal analysis, S.A.; investigation, S.A.R.; resources, S.A.R.; data curation, S.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.; writing—review and editing, S.A.; visualization, S.A.; supervision, S.A.R.; project administration, S.A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the University of Sharjah Research Ethics Committee (Project identification code: REC-25-01-24-01-PG).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdelrahman, R., & Ismail, M. E. (2022). The psychological distress and COVID-19 pandemic during lockdown: A cross-sectional study from United Arab Emirates (UAE). Heliyon, 8(5), e09422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenda, D. (2023). Empowering female entrepreneurs in the Middle East. World Economic Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Al Issa, H. E. (2021). The impact of improvisation and financial bootstrapping strategies on business performance. EuroMed Journal of Business, 16(2), 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R., MacCrimmon, K., & Oesch, J. (1996). The decision to start a new venture: Values, beliefs, and alternatives, babson college/kauffman foundation entrepreneurship research conference. University of Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, A., Davis, P., Liadze, I., & Rienzo, C. (2013). Evaluating changes in bank lending to UK SMEs over 2001–2012—Ongoing tight credit? NIESR Discussion Paper (408). NIESR. [Google Scholar]

- Autio, E., Nambisan, S., Thomas, L. D., & Wright, M. (2021). Digital affordances, spatial affordances, and the genesis of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 15(2), 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartik, A. W., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z. B., Glaeser, E. L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. T. (2020). How are small businesses adjusting to COVID-19? early evidence from a survey (No. w26989). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Basit, A., Hassan, Z., & Sethumadhavan, S. (2020). Entrepreneurial success: Key challenges faced by Malaysian women entrepreneurs in 21st century. International Journal of Business and Management, 15(9), 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J. R., Bird, B. J., & Singh, S. (2023). The impact of entrepreneurial experience on new venture performance: The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 19, e00331. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T. (2007, April 26–27). Financing constraints of SMEs in developing countries: Evidence, determinants and solutions [Conference session]. KDI 36th Anniversary International Conference (pp. 26–27), Seoul, Republic of Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Beriso, B. S. (2021). Determinants of economic achievement for women entrepreneurs in Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhide, A. (1991). Bootstrap finance: The art of start-ups. Harvard Business Review, 70(6), 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen, & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brush, C. G., Carter, N. M., Gatewood, E. J., Greene, P. G., & Hart, M. M. (2004). Women entrepreneurs, growth, and implications for the classroom. In Coleman Foundation White Paper Series for the United States Association for Small Business and Entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurship in a Diverse World (pp. 47–91). Elizabeth J. Gatewood. [Google Scholar]

- Brush, C. G., Carter, N. M., Gatewood, E. J., Greene, P. G., & Hart, M. M. (2006). The use of bootstrapping by women entrepreneurs in positioning for growth. Venture Capital, 8(1), 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelleras, J. L., & Hoxha, D. (2010). Start-up size and subsequent firm growth in Kosova: The role of entrepreneurial and institutional factors. Post-Communist Economies, 22(3), 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, J. C., & Sequeira, J. M. (2007). Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent: A theory of planned behavior approach. Journal of business Research, 60(10), 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N., Brush, C., Greene, P., Gatewood, E., & Hart, M. (2003). Women entrepreneurs who break through to equity financing: The influence of human, social and financial capital. Venture Capital: An international journal of entrepreneurial finance, 5(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., & Kar, A. K. (2022). Why do small and medium enterprises adopt digital technologies? Enablers and barriers of digital transformation in SMEs. Journal of Business Research, 139, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Cliff, J. E. (1998). Does one size fit all? Exploring the relationship between attitudes towards growth, gender, and business size. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(6), 523–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, A., Daunfeldt, S. O., Johansson, D., & Wennberg, K. (2023). High-growth firms: The role of human capital and entrepreneurship policies. Journal of Business Venturing, 38(1), 106287. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, A., & Marques, L. (2020). Motivation and experience in symbiotic events: An illustrative example grounded in culture and business events. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 12(2), 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C., Justo, R., & De Castro, J. O. (2021). Does family business social capital constrain or enable the firm’s corporate social responsibility performance? The role of external uncertainties and family firm R&D investment. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 12(2), 100388. [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carolis, D. M., & Saparito, P. (2006). Social capital, cognition, and entrepreneurial opportunities: A theoretical framework. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T., Shirokova, G. V., & Tsukanova, T. V. (2020). Context matters: The importance of university and family for young nascent entrepreneurs. Poccийcкий жypнaл мeнeджмeнтa, 18(2), 127–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elam, A. B., Brush, C. G., Greene, P. G., Baumer, B., Dean, M., & Heavlow, R. (2019). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2018/2019 women’s entrepreneurship report. Global Entrepreneurship Research Association. [Google Scholar]

- Farrukh, M., Khan, A. A., Khan, M. S., Ramzani, S. R., & Soladoye, B. S. A. (2017). Entrepreneurial intentions: The role of family factors, personality traits and self-efficacy. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 13(4), 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoki, O. (2014). The Financial Bootstrapping Methods Employed by New Micro Enterprises in the Retail Sector in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(3), 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, M. (2018). Bootstrapping practice and motivations for its use in micro, small and medium enterprises [Doctoral dissertation, Dublin City University]. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons, M., Hogan, T., & Hayden, M. T. (2023). Tying the knot–linking bootstrapping and working capital management in established enterprises. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 26(6), 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M., Haase, H., & António, D. (2020). Influence of failure factors on entrepreneurial resilience in Angolan micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- GEM. (2023). Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/reports/womens-entrepreneurship (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Grichnik, D., Brinckmann, J., Singh, L., & Manigart, S. (2013). Beyond environmental scarcity: Human and social capital as driving forces of bootstrapping activities. Journal of Business Venturing, 29, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundry, L. K., & Welsch, H. P. (2001). The ambitious entrepreneur: High growth strategies of womenowned enterprises. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(5), 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q., Wu, Z., Jahanger, A., Ding, C., Guo, B., & Awan, A. (2023). The spatial impact of digital economy on energy intensity in China in the context of double carbon to achieve the sustainable development goals. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(13), 35528–35544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. (2019). The Behavioural Mediator between Entrepreneurship Intention of Students and Resources: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of the Gujarat Research Society, 21(11), 416–423. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (Vol. 6). Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, V. (2021). Artificial Intelligence in the Gulf: Women and the Fourth Industrial Revolution: An Examination of the UAE’s National AI Strategy (E. Azar, & A. N. Haddad, Eds.). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisrich, R. D., & Brush, C. G. (1983). The women entrepreneur: Implications of family, educational and occupational experience. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 2(1), 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Hisrich, R. D., & Öztürk, S. A. (1999). Women entrepreneurs in a developing economy. Journal of Management Development, 18(2), 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. C. (2023). Discovery brand authentic and sensory experience influencing word of mouth with mediation and moderation setting. Current Issues in Tourism, 27, 4185–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, A., Tan, C. S. L., & Venugopal, V. (2020). How do women entrepreneurs strategize growth? An investigation using the social feminist theory lens. Journal of Small Business Management, 58(2), 259–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITC. (2015). Available online: https://www.shetrades.com/about-the-initiative/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Jiang, X., Liu, H., Fey, C., & Jiang, F. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation, network resource acquisition, and firm performance: A network approach. Journal of Business Research, 87, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannisson, B. (1988). Business formation—A network approach. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 4(3–4), 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph Jerome, J. J., Sonwaney, V., & ON, A. (2023). Modelling the factors affecting organizational flexibility in MSMEs. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing, 17(3), 596–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargwell, S. A. (2012). A comparative study on gender and entrepreneurship development: Still a male’s world within UAE cultural context. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(6), 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, J. A. (1992). A psychosocial cognitive model of employment status choice. Entrepreneurship and Theory Practice, 17(1), 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T., Down, S., & Minniti, M. (2014). Ageing and entrepreneurial preferences. Small Business Economics, 42(3), 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M., Hassan, R. B. A., & Khan, M. A. (2020). Influence of Prior Family Business Exposure, Motivation and Growth Intention on Financial Bootstrapping among women entrepreneurs: Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Competencies. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(18), 1858–1869. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. A., Rathore, K., & Sial, M. A. (2020). Entrepreneurial orientation and performance of small and medium enterprises: Mediating effect of entrepreneurial competencies. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences (PJCSS), 14(2), 508–528. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. A., Tarif, A., & Zubair, D. S. S. (2016). Non-financial incentive system and organizational commitment: An empirical investigation. Pakistan Business Review, 18(1), 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. A., Zubair, S. S., Rathore, K., Ijaz, M., Khalil, S., & Khalil, M. (2021). Impact of entrepreneurial orientation dimensions on performance of small enterprises: Do entrepreneurial competencies matter? Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1943241. [Google Scholar]

- Klepper, S. (2001). Employee startups in high-tech industries. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10(3), 639–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugesen, K., Ludvigsson, J. F., Schmidt, M., Gissler, M., Valdimarsdottir, U. A., Lunde, A., & Sørensen, H. T. (2021). Nordic health registry-based research: A review of health care systems and key registries. Clinical Epidemiology, 533–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, K. H., & Güldenberg, S. (2021). Growth intentions and scaling up: The role of technology, resources, and capabilities in digital entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 57(1), 355–372. [Google Scholar]

- Lentz, B. F., & Laband, D. N. (1990). Entrepreneurial success and occupational inheritance among proprietors. Canadian Journal of Economics, 23(3), 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L., & Du, M. (2024). How digital finance shapes residents’ health: Evidence from China. China Economic Review, 87, 102246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K. Q., & Zhang, W. (2023). Assessing univariate and multivariate normality in PLS-SEM. Data Analysis Perspectives Journal, 4(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, A. B., Berman, A., Reisel, W. D., Fuxman, L., Grigoriou, N., & Tehseen, S. (2023). Entrepreneurial marketing intentions and behaviours among students: Investigating the roles of entrepreneurial skills, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and family business exposure. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 21(1), 123–148. [Google Scholar]

- Malmström, M., & Hällerstrand, L. (2023). Bootstrap financing. In The palgrave encyclopedia of private equity (pp. 1–7). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Manolova, T. S., Brush, C. G., Edelman, L. F., & Elam, A. (2020). Pivoting to stay the course: How women entrepreneurs take advantage of opportunities created by the COVID-19 pandemic. International Small Business Journal, 38(6), 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M., & Chatterjee, S. (2023). Examining the influence of trustworthiness, financial rewards, and admiration for crowdsourcing in the post COVID-19 period. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, M. J. (2017). Women’s Business Ownership: Data from the 2012 Survey of Business Owners. U.S. Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy, 13(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, D. (2015). Global firms and smart technologies: IBM and the reduction of cities. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 40(4), 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzer, L. (2023). Women on a mission: MENA female entrepreneurs are making waves in the region. MENASource. [Google Scholar]

- Mpi, D. L. (2019). Encouraging Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMES) for economic growth and development in Nigeria and other developing economies: The role of ‘the Igbo apprenticeship system’. The Strategic Journal of Business & Change Management, 6(1), 535–543. [Google Scholar]

- Muravyev, A., Talavera, O., & Schäfer, D. (2009). Entrepreneurs’ gender and financial constraints: Evidence from international data. Journal of Comparative Economics, 37(2), 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, H., & Malik, F. (2022). Role of Digital Platforms in Entrepreneurial Processes: The Resource Enabling Perspective of Startups in Pakistan. In Innovation practices for digital transformation in the global south: IFIP WG 13.8, 9.4, invited selection (pp. 130–148). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Neely, L., & Van Auken, H. (2012). An examination of small firm bootstrap financing and use of debt. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 17(1), 1250002–1250012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A., Obschonka, M., Moeller, J., & Chandan, G. G. (2022). Entrepreneurial motivation and venture performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 37(1), 106191. [Google Scholar]

- Nkwinika, E. (2023). Exploring ways to construction of a business bootstrapping model to equip emerging micro business in the first year of operation in South Africa. Technology Audit and Production Reserves, 6(4/74), 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric thseory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Okafor, C., & Amalu, R. (2012). Motivational patterns and the performance of entrepreneurs: An empirical study of women entrepreneurs in South-West Nigeria. International Journal of Applied Behavioral Economics (IJABE), 1(1), 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Olanrewaju, O., Hossain, M. A., Whiteside, N., & Mercieca, P. (2020). Social media and entrepreneurship research: A literature review. International Journal of Information Management, 50, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perveen, M. (2019). Life stress, personality and psychological well-being of women entrepreneurs, service holders and homemakers [Doctoral dissertation, University of Dhaka]. [Google Scholar]

- Pret, T., & Cogan, A. (2019). Artisan entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(4), 592–614. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, X. (2012). Prior experience, social network, and levels of entrepreneurial intentions. Management Research Review, 35(10), 945–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P. D., & White, S. B. (1997). The entrepreneurial process: Economic growth, men, women, and minorities. Praeger Pub Text. [Google Scholar]

- Rita, M. R. (2019). Financial bootstrapping: External financing dependency alternatives for SMEs. Jurnal Ekonomi dan Bisnis, 22(1), 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rita, M. R., & Nastiti, P. K. Y. (2024). The influence of financial bootstrapping and digital transformation on financial performance: Evidence from MSMEs in the culinary sector in Indonesia. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2363415. [Google Scholar]