Abstract

Household savings are a long-term financial issue that can undermine the financial well-being of American families if not addressed. This study examines financial planning strategies through the Behavioral Life-Cycle (BLCH) hypothesis, focusing on long-term savings goals, financial safety nets, and foreseeable expenses. Using data from the 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances, a moderated mediation model explores how financial safety nets, self-control, and mental accounting influence saving habits. The findings show that long-term savings goals significantly mediate the relationship between financial safety nets and saving habits, while foreseeable expenses do not significantly moderate this relationship. These results highlight the importance of goal setting in promoting saving behaviors, regardless of specific financial needs. Policymakers can leverage these findings to design initiatives that encourage structured savings programs, while financial advisors should emphasize goal-setting strategies to help households improve their financial security. This research contributes to a deeper understanding of the behavioral and economic factors that drive personal savings, offering valuable insights for both policymakers and financial practitioners aiming to boost financial well-being in households.

1. Introduction

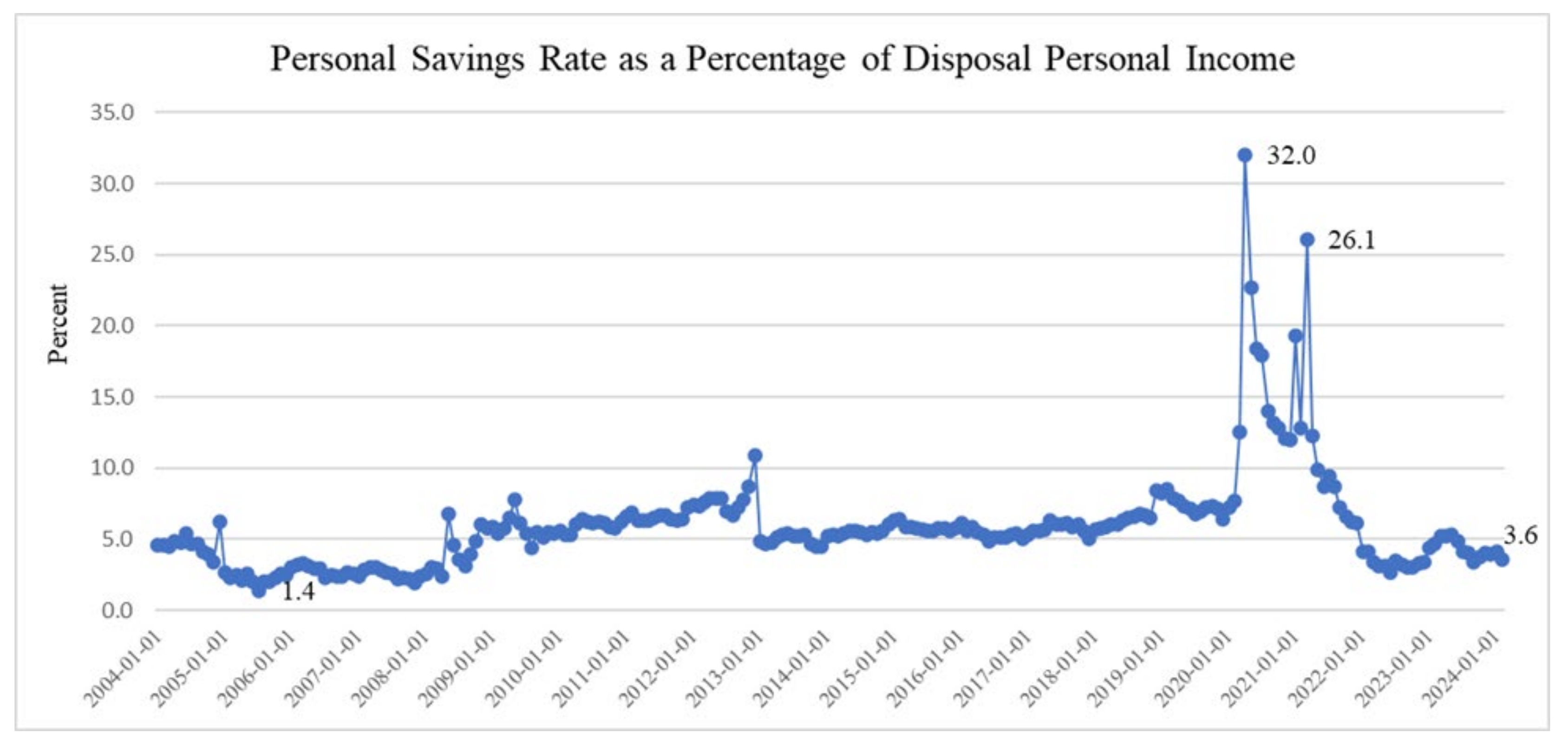

U.S. household savings rates have been artificially elevated in recent years due to unprecedented government transfer payments and a curtailment of consumer spending driven by COVID-19-related shutdowns (Aladangady et al., 2022; Abdelrahman & Oliveira, 2023). However, economists report that since 2021, savings levels have dipped below pre-pandemic levels (see Figure 1), a concerning trend given the importance of personal savings to the economic stability and well-being of the household. The Bureau of Economic Analysis calculates the personal savings rate as the “amount of income left after people spend money and pay taxes” (U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2024). Economists and scholars have used personal savings rates to monitor financial behaviors and to assess the health of consumers.

Figure 1.

U.S. Households Personal Savings Rate (2004–2024). Note. Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (2024). Personal savings rate.

Personal savings rates are essential, as these rates directly influence the accumulation of household savings assets, shaping overall financial stability and preparedness for future outcomes, including retirement, emergency reserves, and major purchases (Fisher & Anong, 2012). Savings assets are defined as income minus consumption (Browning & Lusardi, 1996). Individuals who can postpone current pleasures or defer today’s enjoyment for the sake of future rewards tend to demonstrate stronger saving behaviors, thereby using self-control or self-regulation to create more savings assets (Brounen et al., 2016; Winchester et al., 2011). Savings assets would also support well-being and reduce the incidence of wellness factors such as loneliness and depressive symptoms (Bialowolski et al., 2024; Martin & Hill, 2015). Additionally, studies have also found that the way we frame our savings goals can influence the amount we save. For example, specifying the exact amount to be saved, compared to only saving as much as possible, is associated with greater savings (Ülkümen & Cheema, 2011). The practice of deferring current consumption to create savings assets is an invaluable behavior that positions an individual for future financial success.

Despite their importance, households have sometimes reported difficulty in reaching and maintaining levels of liquid assets sufficient to meet their financial needs. Collins and Gjertson (2013) explain that liquid savings assets allow households to absorb unexpected financial events that exceed current income and describe individuals unable to accumulate these assets as financially fragile. While their study focused on individual financial events, less is known about the influence of widespread economic events on factors that affect consumer saving behaviors, such as a pandemic, an economic shutdown, or government transfer payments.

Financial professionals have become increasingly influential in shaping both consumer saving behavior and the amount they save. For example, individuals who work with financial professionals are more likely to resist short-sighted financial decision-making and are more committed to long-term investment decisions than those who do not (Winchester et al., 2011; Montmarquette & Viennot-Briot, 2015). Financial professionals monitor and encourage personal savings rates, savings assets, and related behaviors due to their significant impact on future financial outcomes. Thus, we expect widespread economic events to directly impact financial professionals’ work with individuals and their savings assets. Gaining insight into this and other factors that influence saving behaviors will empower financial professionals to assist consumers and potentially address barriers to achieving their savings objectives.

We aim to add to the literature on savings assets and behaviors by examining how the behavioral components of the behavioral life-cycle (BLCH) model can be used to support consumers in developing productive financial habits like saving. This study specifically examines the fungibility of savings assets in a post-pandemic environment. Our analysis (i) begins with an examination of households’ financial safety nets, (ii) explores how long-term savings goals serve as mediators, (iii) investigates whether the presence of foreseeable expenses influences saving habits, and (iv) demonstrates that within the U.S. context, having savings goals mediates the relationship between financial safety nets and saving habits and considers the role foreseeable expenses play as a moderator to the relationship. We hypothesize that the effect of having foreseeable expenses moderates the relationship between savings goals and saving habits.

2. A Literature Review

Saving behaviors have been studied extensively in the literature. However, the importance of this behavior to future financial outcomes warrants regular examination of its factors of influence and periodic review of potential savings strategies that may help to promote successful financial outcomes. Changes in market environments, societal norms, trends in consumption patterns, along with new financial product offerings each have the potential to influence or change savings patterns (Gargano & Rossi, 2024). Further, the propensity to save is an important financial behavior with the potential to influence most other financial objectives, e.g., retirement savings goals, emergency reserve targets, etc. (Yoon & Hanna, 2024). Despite extensive research, the interplay between financial safety nets, self-control, and long-term goals has not been fully explored. This study builds on the existing literature by examining how these factors interact using a moderated mediation framework.

2.1. Behavioral Influence and Savings

People often rely on mental shortcuts and established habits when making financial decisions, particularly when faced with complex choices. Research suggests that how savings decisions are framed can influence behavior. For example, individuals are more likely to save when goals are clearly defined and broken into manageable time frames (Hershfield et al., 2020; Shin et al., 2019).

Self-control and financial planning strategies also play a role in shaping saving habits. Prior studies have found that individuals who set specific savings rules or goals tend to save more over time (Shefrin & Thaler, 1992; Kim & Hanna, 2017; Liu et al., 2019). Using data from the 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances, Kim and Hanna (2017) found that structured savings rules were associated with stronger saving behavior. Similarly, Rha et al. (2006) showed that saving for specific purposes—such as retirement, major purchases, or emergency funds—was linked to a higher likelihood of saving.

While previous research has explored the role of goal-setting in financial decisions, whether the presence of a financial safety net strengthens self-control for savings decisions has not been adequately examined. This study builds on the existing literature by examining how financial safety nets and long-term goals relate to saving habits using the latest available data. By considering the role of planning and anticipated expenses, this study provides a broader perspective on the factors that encourage consistent saving.

2.2. Factors of Influence on Savings

The motivation for saving behavior has largely been driven by future funding needs, such as retirement or wealth creation (Fisher & Anong, 2012; Hanna & Lee, 2015). However, more recent studies have also considered the influence of factors such as psychological characteristics (Cobb-Clark et al., 2016; Asebedo et al., 2019) and relationship status (Chawla & Svec, 2023) to better understand what may explain the saving behaviors seen by practitioners. For example, in older adults, Asebedo et al. (2019) found that financial self-efficacy was a significant factor in saving, and personality traits also indirectly influenced saving behaviors in this population. Self-control was also found to positively relate to saving behaviors (Liu et al., 2019), and savings goals were found to positively encourage savings attitudes (Cho et al., 2014).

Demographic patterns in saving behavior found in prior studies have largely aligned with expectations. For example, households with higher levels of income and net worth were more likely to save, as well as those who expected their future income to be higher than their current income (Yuh & Hanna, 2010). The same study found that households with access to external financial resources were also more likely to be savers. Differences in saving behavior have been found by gender, race, and ethnicity, as well as health status, with those reporting poor health as more likely to save than those in good health (Yuh & Hanna, 2010; Fisher et al., 2015).

Historically, financial professionals have underscored the importance of saving early and emphasized the advantages derived from factors such as compounding (Liu et al., 2019). Scholars have also identified specific behaviors as influential to having a savings account, for example, planning for how money will be spent or saved or having written financial goals (Croy et al., 2010; Copur & Gutter, 2019). Further, research indicates that setting savings goals serves to counteract tendencies toward excessive spending (Liu et al., 2019; Sui et al., 2021). Shefrin and Thaler (2004) have described this principle as temptation-inducing impatience. Strategies aimed at improving savings rates have included approaches such as increasing financial education initiatives and introducing default saving options (Lusardi, 2008).

The propensity to save is an important financial behavior with the potential to influence most other financial objectives, e.g., retirement savings goals, emergency reserve targets, etc. (Yoon & Hanna, 2024). This study aims to add to the literature by examining the role a financial safety net plays in influencing saving behaviors and determining if factors such as goal-setting and anticipated expenses may impact the relationship.

2.3. Managing Foreseeable Expenses

Research on household saving behavior has identified several key factors that significantly influence an individual’s likelihood of saving. Rha et al. (2006) found that having one or more saving rules significantly increases the likelihood of saving, with the expectation of major foreseeable expenses also positively influencing saving behavior. Their study demonstrated that specific savings goals for retirement, precautionary purposes, or future purchases were associated with higher savings rates, while goals related to education had a negative impact. Similarly, Hogarth and Anguelov (2003) highlighted the importance of clear financial motivations in increasing savings among low-income households, showing that families expecting major expenses within the next 5 to 10 years were 1.2 times more likely to save. Additionally, Hogarth et al. (2005) found that households anticipating significant expenses were more likely to maintain bank accounts, indirectly promoting better saving habits through structured financial management.

These findings align with BLCH, which incorporates psychological factors like self-control and mental accounting into saving behavior models. BLCH suggests that individuals use mental accounting and commitment devices, such as saving rules and specific goals, to manage their finances effectively. Further supporting this, Ülkümen and Cheema (2011) found that specific savings goals lead to greater savings, and Asebedo et al. (2019) emphasized the role of psychological factors in saving behavior. Together, these studies underscore the importance of setting clear savings goals and anticipating future expenses as strategies to enhance saving habits and provide support for examining foreseeable expenses as a potential moderator in the relationship between savings goals and saving habits.

3. Theory

The Life-Cycle Savings Theory, initially proposed by Modigliani and Brumberg (1954), posits a normative framework for household savings and consumption, advocating for an optimal consumption path to maximize lifetime utility. This model suggests consumers aim to smooth consumption across different life stages, adjusting their savings and spending to maintain constant utility. Yet, empirical observations often reveal deviations from these theoretical predictions, attributable to behavioral factors unaccounted for in the initial model. Subsequent enhancements, notably the Behavioral Life-Cycle Hypothesis (Shefrin & Thaler, 1988), incorporate insights from behavioral economics like self-control and mental accounting, offering a more nuanced understanding of financial decision-making that acknowledges psychological influences on consumer behavior. This evolution signifies a critical refinement of classical economic theories, emphasizing the importance of aligning financial policies and interventions with the complex reality of consumer decision-making processes.

While the normative Life-Cycle Hypothesis offered rational assumptions explaining households’ saving behavior, the BLCH provides a robust theoretical foundation for examining contemporary household financial behaviors. Shefrin and Thaler (1988) introduced behavioral concepts such as self-control, mental accounting, and framing in BLCH. They discussed how self-control can be challenging for individuals’ saving habits, such as delaying gratification for long-term savings. They introduced mental accounting, which is how people categorize foreseeable expenses, aiding in effective resource allocation. Additionally, framing is presented as a way that the structuring of information impacts financial decisions, emphasizing the influence of achieving long-term savings goals. Our study builds on this framework by testing a moderated mediation model that intricately weaves together several key components of financial decision-making: households’ financial safety net, savings goals, foreseeable expenses, and saving habits.

3.1. Households’ Financial Safety Net—Resources

The financial safety net of households, conceptualized as the independent variable in our model, is a crucial element rooted in the life-cycle savings theory. This theory suggests that households accumulate savings as a safety net to maintain consumption stability over their life cycle, particularly to buffer against future uncertainties or income fluctuations (White et al., 2022). The BLCH further acknowledges that real-life savings are not always aligned with idealized, rational models due to behavioral factors like risk perception and future uncertainty.

3.2. Long-Term Savings Goals as the Mediator—Framing

Savings goals serve as the mediator in our model, representing the deliberate planning aspect of the life-cycle theory. The framework posits that individuals set savings goals to ensure a smooth consumption path, balancing present needs with future aspirations. This aligns with the BLCH’s emphasis on mental accounting, where individuals mentally allocate resources for specific objectives, potentially impacting their saving behaviors.

3.3. Foreseeable Expenses as the Second-Stage Moderator—Mental Accounting

Incorporating foreseeable expenses as a second-stage moderator adds a layer of complexity to our model, resonating with the behavioral aspects of the life-cycle theory. This recognizes that individuals’ savings decisions are not only influenced by their set goals but also by their anticipation of future expenses. It acknowledges that foreseeable expenses can significantly modulate the relationship between savings goals and actual saving habits.

Foreseeable expenses, which include anticipated major financial outlays such as education costs, home purchases, or significant medical expenses, play a pivotal role in financial planning. The expectation of these expenses can act as a powerful motivator for individuals to save (Hogarth & Anguelov, 2003; Rha et al., 2006). When individuals foresee substantial future costs, this study posits that they would be more likely to adopt disciplined saving behaviors to prepare for these financial demands. This preparation can take the form of specific savings accounts, budgeting strategies, or investments in financial products designed to grow savings over time.

3.4. Saving Habit as the Dependent Variable—Self-Control

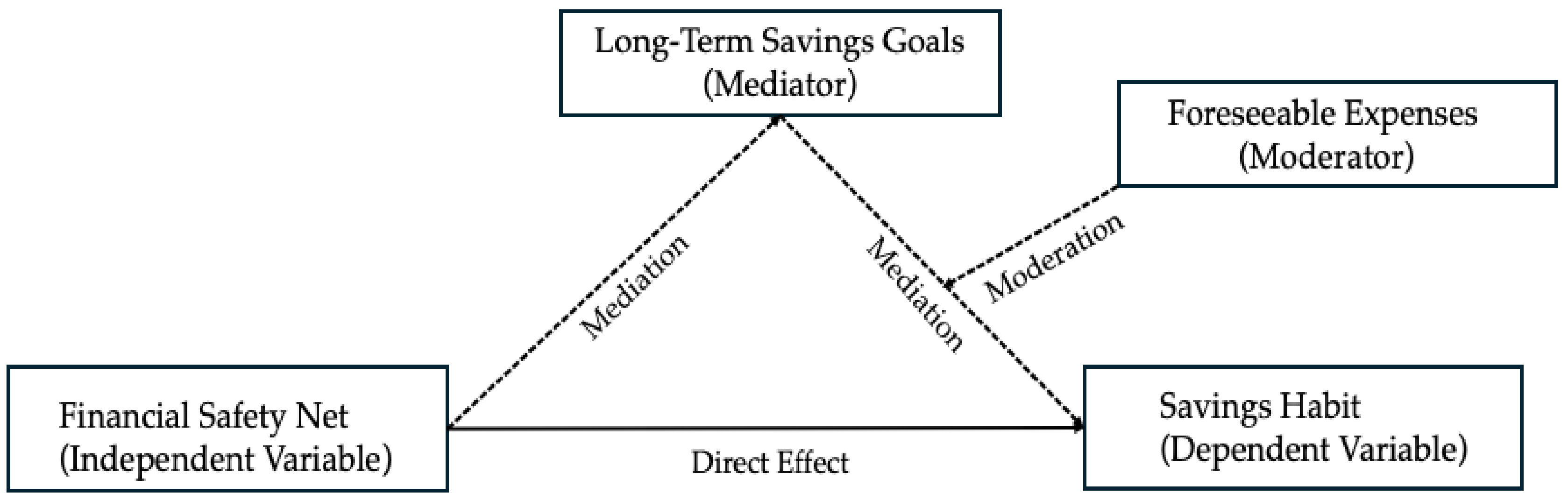

Finally, the saving habit, our dependent variable, is the culmination of these interlinked factors. It represents the actualization of the life-cycle savings theory and its behavioral nuances in everyday financial practices. Saving habit embodies the concept of consumption smoothing and reflects how households’ financial safety nets, savings goals, and expected future expenses collectively shape real-life saving behaviors. The conceptual framework for this study is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework for Moderated Mediation Analysis. Note. Long-term savings goals serve as mediators, and foreseeable expenses are the second-stage moderators.

4. Methodology

4.1. Dataset

The dataset for this study was the 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), the most recent version of the dataset. The SCF is a triennial interview survey of U.S. families sponsored by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System with the cooperation of the U.S. Department of the Treasury (Bricker et al., 2017). The Federal Reserve Board’s triennial Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) collects information about family incomes, net worth, balance sheet components, credit use, and other financial outcomes. Compared to other datasets, the SCF utilizes a sample design that includes both a nationally representative random sample and an oversample of wealthy households, facilitating a thorough examination of household financial health across diverse income and wealth categories. The SCF contains detailed information on U.S. households’ credit and debt use combined with comprehensive details on household characteristics and financial attitudes (Zinman, 2004), as well as a number of attitudinal and expectation questions (Hanna et al., 2018; Kennickell & Shack-Marquez, 1992). Therefore, the SCF is particularly well-suited for testing the topic of this study.

There are 4595 households represented by 22,975 records in the dataset. As Hanna et al. (2018) noted, most of the information, such as income, is for the Primary Economic Unit, which may be a subset of the household. However, for convenience, we will follow other authors (Kim & Hanna, 2017; Hanna et al., 2018; Shin et al., 2019) in referring to households. This paper also emphasizes the importance of preserving household representativeness within the survey design by reflecting each household’s intended family-level weight, ensuring that every household’s overall contribution to the analysis is maintained.

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Dependent Variable

Saving Habit

The dependent variable was constructed from the question, “Over the past year, would you say that your spending (excluding spending on investments and durables) exceeded your income, was about the same as your income, or that you spent less than your income?” A binary variable was coded as 1 if the respondent reported that spending (excluding spending on investments and durables) was less than income and coded as 0 otherwise.

The dependent variable was, thus, an indicator of the potential for saving. Following Rha et al. (2006), we used this variable to estimate the probability of saving over the past year.

4.2.2. Explanatory Variable

Financial Safety Net

The financial safety net variable is measured using the following question: “In an emergency, could you (or your {husband/wife/partner}) get financial assistance of USD 3000 or more from any friends or relatives who do not live with you?” Responses were coded as 1 for “Yes” and 0 for “No”.

While this measure captures external financial support rather than personal assets, it aligns with the BLCH by recognizing that individuals manage resources through both personal savings and external financial networks (Shefrin & Thaler, 1988). Access to such assistance can serve as a temporary financial buffer, reducing liquidity constraints and influencing long-term financial decisions (Rha et al., 2006; Hanna & Lee, 2015; Ouyang et al., 2019). Households that anticipate financial support may allocate personal savings differently, prioritizing long-term goals over precautionary reserves (Yuh & Hanna, 2010).

Thus, while not a direct measure of accumulated wealth, this variable reflects an important aspect of financial security and complements traditional measures of financial resilience (White et al., 2022).

Long-Term Savings Goal

In developing a definition for long-term (LT) savings goals, recent studies have categorized these goals using frameworks such as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 1943; Hanna & Lee, 2015). According to Rha et al. (2006) and Hanna and Lee (2015), savings goals can be categorized into levels corresponding to Maslow’s hierarchy, including basic needs, emergency/safety, retirement/security, love/family, esteem/luxuries, self-actualization, and others. Categories above emergency/safety are often considered long-term, depending on the context. For example, Maslow’s framework places education and family-related expenses (weddings, children, and burial expenses) in the love/family category, which can be viewed as either short-term or long-term depending on individual circumstances, though they are typically retained as long-term goals (Maslow, 1943). In contrast, older studies such as Rha et al. (2006) categorized savings goals into retirement, precautionary, purchase, children, and future/own education, which aligns more closely with our study. Precautionary goals, such as unemployment reserves or rainy-day funds, fall under near-term goals and would likely be excluded from long-term savings. However, categories like future education, wealth preservation, and maintaining lifestyle, often categorized under esteem/luxuries or retirement in both frameworks, are logical to include as LT savings. Charitable giving, while considered part of self-actualization, is debatable in terms of timeframe but would be retained under the broader Maslow interpretation.

Foreseeable Expenses

Foreseeable expenses were measured with the question asking respondents, “In the next five to ten years, are there any foreseeable major expenses that you (and your family) expect to have to pay for (yourself/yourselves), such as educational expenses, purchase of a new home, health care costs, support for other family members, or anything else?” Yes was recorded as 1; No was recorded as 0. The overview and descriptions of key variables used in the empirical analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview and Descriptions of Key Variables Used in the Empirical Analysis.

4.2.3. Control Variables

Households’ sociodemographic variables, such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment status, marital status of the respondent, homeownership, household income, household financial asset, financial independence, economy expectations, and retirement horizon, were controlled. Other household financial information was also included, such as the number of financial dependents, the presence of an emergency fund, and objective and subjective financial knowledge.1

4.3. Analysis

This study investigates the relationships among financial safety nets, long-term goals, and saving habits. Given the binary nature of our primary variables, we utilized the Phi coefficient to assess the bivariate associations among them, revealing a weak positive correlation across all key variables, with the highest Phi coefficient of 0.151 between the financial safety net and saving habits. To test our conceptual model l, as shown in Figure 1, we adopted a second-stage moderated mediation model. Specifically, we run mediation analysis with 1000 bootstrap replications, with the presence of a long-term savings goal serving as the mediator in the relationship between the financial safety net and saving habits. Subsequently, to examine a combined moderated mediation effect, we introduced the variable of foreseeable expenses as a moderator in the relationship between long-term goals and saving habits. In this analysis framework, the financial safety net was specified as the independent variable, saving habits as the dependent variable, long-term goals as the mediator, and foreseeable expenses as the moderator. Control variables were incorporated at both stages of the analysis to account for potential confounding factors. The bootstrap approach offers a data-driven methodology for estimating standard errors that carefully addresses the complexities of the SCF survey design and the additional uncertainty from its multiple imputations. Meanwhile, the mediation and moderated mediation analyses in this study apply the household-level weight to maintain representativeness, thereby facilitating robust inference. The direct and indirect effects on saving habits were analyzed in detail.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for all variables under consideration are presented in Table 2. A total of 66.65% indicated that they had access to more than USD 3000 financial support from friends or relatives in emergencies. A total of 64.86% of the respondents reported setting long-term financial goals. Nearly 6 out of 10 (59.05%) surveyed respondents demonstrated the habit of saving extra money. Over half (53.87%) anticipated incurring significant expenses in the next 5 to 10 years. On average, respondents correctly answered two out of three questions designed to objectively assess their financial knowledge. Moreover, on a self-assessment scale ranging from 0 to 10, participants rated their perceived financial knowledge at an average of 7.510. Married or cohabiting males represented the largest group at 42.48%, while unmarried males constituted the smallest group at 13.85%. Education levels varied, with 8.62% having attained a high school education or less and 26.19% holding a bachelor’s degree. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 95, with an average age of 54.01. More than half (59.71%) of respondents identified as non-Hispanic white. A total of 7.13% reported having children under 18, and 67.70% were homeowners. The logarithmic average of income stood at 11.67, and financial assets at 11.12. Regarding perceptions of retirement income adequacy, 27.00% found it very satisfactory, whereas 16.20% deemed it completely inadequate, based on their current or expected income from all sources. Economic outlooks were pessimistic among nearly half (48.08%) of the respondents who anticipated a worse economy over the next year, while only 15.21% expected a better economy. Furthermore, when it came to managing their finances, higher proportions of respondents prioritized planning or budgeting for the next few years (25.94%) and the next 5 to 10 years (26.71%) than other time frames.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics (N = 4595).

5.2. Main Findings from Moderated Mediation

The key findings on moderated mediation suggest that households with financial safety nets as resources were more likely to develop a saving habit of spending less than their income, demonstrating self-control. Also, part of this relationship operates through the presence of long-term savings goals, which align with the deliberate planning aspect of life-cycle theory. However, the influence of long-term savings goals on saving habits did not significantly change regardless of whether households anticipated major future expenses, a concept tied to mental accounting.

We presented the analysis results in two steps. First, the mediation analysis generated a 1000-bootstrap confidence interval without zero for the significance test. The results of the mediation analysis are reported in Table 3. In the logistic regression analysis examining the role of having a long-term savings goal as a mediator between financial safety nets and saving habits, the results indicated a positive direct association. Individuals with access to USD 3000 or more financial support from friends or relatives were more likely to report having long-term goals (OR = 1.316, p < 0.001), and a positive relationship was observed between long-term goals and saving habits (OR = 1.172, p < 0.001), confirming the foundational relationships necessary for mediation to occur. The mediation effect results suggest that long-term savings goals serve as the mediator in the relationship between the financial safety net and saving habits. Specifically, the average mediation effect of the financial safety net on saving habits through long-term goals was estimated at 0.002, with the average direct effect as 0.030. This suggests that although long-term savings objectives play an important role in mediating this relationship, a significant proportion of the impact of the financial safety net on saving behaviors occurs directly. The total effect of the financial safety net on saving habits was found to be 0.032, of which approximately 6.31% was mediated by long-term goals.

Table 3.

Mediating Effect of Long-Term Goals on the Relationship Between Financial Safety Nets and Saving Habits.

Then, with the moderator of foreseeable expenses added into the model (Table 4), there was a positive and significant association between the financial safety net and saving habits (OR = 1.146, p < 0.001), as well as between long-term goals and saving habits (OR = 1.154, p < 0.001) in the logistic regression. Preceding relationships identified in the mediation analysis were validated. The moderated mediation model included an interaction term to capture the moderating effect of foreseeable expenses on the relationship between long-term savings goals and saving habits (Table 4). However, the interaction term was not significant in the analysis, suggesting that the effect of long-term goals on saving habits does not significantly vary with the presence of anticipated major future expenses. The average mediation across the presence and absence of a financial safety net was estimated at 0.002. The average direct effect of the financial safety net on saving habits was 0.028, and the total effect was approximately 0.030. Therefore, approximately 6.05% of the relationship between financial safety net and saving habits was mediated by long-term savings goals.

Table 4.

Results of moderated mediation analyzing the impact of foreseeable expenses as a moderator and long-term goals as a mediator on the relationship between financial safety nets and saving habits.

Objective financial knowledge was positively associated, while subjective financial knowledge was negatively associated with having a long-term savings goal. Age was positively associated, although age squared was negatively associated with the long-term savings goal. Possessing a graduate degree as opposed to having less than a high school education, the presence of dependent children under 18 years old, greater financial assets, higher satisfaction with retirement preparedness, and the anticipation of a worse economy compared to maintaining the same were all factors that positively correlated with setting long-term savings goals. In contrast, being a homeowner and having a budgeting or financial planning horizon of less than 10 years showed a negative correlation with the inclination to set long-term savings goals.

Subjective financial knowledge showed a positive association correlation with saving habits. Individuals with a bachelor’s degree showed a higher likelihood of having saving habits compared to those lacking a high school diploma. A similar pattern for age and its squared term with saving habits appeared as their relationship with long-term goals. Non-Hispanic White respondents were found to have a negative association with saving habits. The presence of dependent children, higher income levels, larger financial assets, greater satisfaction with retirement adequacy, expectations of a better economy compared to an unchanged economy, maintaining a budgeting and planning horizon in the next 5 years compared to having more than 10 years as reference, all demonstrated a positive association with saving habits.

6. Discussion

This study investigated the role the financial safety net plays in influencing saving behaviors and examined the impact of psychological factors such as self-control and mental accounting on the relationship. When individuals have a financial safety net, our findings showed that savings goals were positively related to having a saving habit. Saving habits served as a proxy for the construct of self-control. Interestingly, we found that anticipated future expenses, the measure used to examine the influence of mental accounting, did not significantly impact the relationship between savings goals and saving behaviors. These findings suggest that simply setting a savings goal can create conditions for better saving habits without the need for a specific expense or reason.

Our findings build upon and extend previous studies that have established a link between financial safety nets and saving behavior. Prior research suggests that households with clearly defined savings goals tend to exhibit stronger saving habits, particularly when those goals are framed as specific financial targets (Rha et al., 2006; Kim & Hanna, 2017). Additionally, Rha et al. (2006) found that foreseeable expenses modestly increased the likelihood of saving; our study does not support this moderating effect. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in economic conditions and consumer sentiment across time. Rha et al. (2006) based their analysis on the 1998 wave of SCF, whereas our study utilizes data from the 2022 SCF. The economic landscape has shifted considerably over this period, with the pandemic-influenced environment characterized by heightened financial uncertainty, inflationary pressures, rising interest rates, and labor market volatility (Ouyang et al., 2025). These factors may have reshaped household financial priorities, leading consumers to adopt more flexible and precautionary savings strategies rather than allocating funds explicitly for anticipated expenses.

The lack of support found for the moderating role of expected future purchases on the relationship between financial resources and saving habits is consistent with prior studies that have highlighted the challenges individuals face in delaying current consumption in order to fund future consumption needs (Shefrin & Thaler, 1992; Rha et al., 2006). One potential explanation is that individuals prioritize financial safety nets and long-term goals over specific upcoming expenses when structuring their saving behaviors. The COVID-19 pandemic may have fundamentally altered consumer psychology, leading individuals to adopt broader, more flexible savings strategies rather than earmarking funds for specific foreseeable expenses. The once-in-a-lifetime COVID experience may have shortened the temporal lens of consumers and could explain why anticipated future expenses did not impact long-term savings goals in our more recent study. This finding is also consistent with Fisher and Anong (2012), who found that medium- and long-term saving horizons were more predictive of saving behaviors than short-term anticipated expenses. This suggests a shift in consumer behavior due to unprecedented economic conditions, warranting further investigation.

Another possible explanation is that households with financial safety nets perceive themselves as having greater financial security, thereby reducing the psychological urgency to explicitly allocate funds for foreseeable expenses. This perspective aligns with research on financial resilience, which suggests that individuals with greater financial resources are more likely to exhibit proactive saving behaviors without necessarily tying them to anticipated expenditures (White et al., 2022).

Trends in personal savings rates tend to ebb and flow over time, sometimes to the detriment of the average consumer. However, as this study confirmed, intentional efforts like specific savings goals are most effective in positioning consumers to achieve their financial goals (Kim & Hanna, 2017). The findings underscore the necessity of reinforcing goal-setting practices within financial advisory services, as these practices can significantly contribute to more disciplined saving behaviors and better financial preparedness.

Saving should be more than only a good financial habit given its importance to nearly all future financial outcomes. So, regularly revisiting our understanding of factors associated with changes in savings rates or motivators of saving behaviors can help us better understand consumer behavior. This study’s focus on long-term savings targets and goals reflects our interest in sustainable saving habits and behaviors and adds to prior studies that focused on broader definitions of savings goals (Rha et al., 2006; Yoon & Hanna, 2024). By focusing on long-term savings goals, this study contributes to a nuanced understanding of how specific financial planning strategies can enhance financial resilience and well-being. Furthermore, this study also examined the influences on saving behaviors in the post-COVID environment of higher interest rates and economic recovery, which extends the work of prior studies using data from pre-COVID periods. Findings from this study support the importance of savings goals, or self-control, on the success of a personal savings plan.

7. Implications

The results of our study highlight the important role of long-term savings goals in a household’s saving habits, as mediated by the presence of a financial safety net. This echoes past research, such as the work by Ülkümen and Cheema (2011), which found that specific savings goals lead to greater accumulation of savings. Financial professionals, particularly planners, should, therefore, emphasize the establishment of clear, specific, and attainable long-term savings goals when advising clients. This approach aligns with the BLCH, which suggests that setting explicit financial targets can help individuals better manage their current and future financial states. Planners should work with clients to identify and articulate these goals, whether they are related to retirement, purchasing a home, or building an educational fund, thereby encouraging disciplined and goal-oriented saving behavior.

Despite the expectation that foreseeable expenses would significantly modulate the impact of long-term goals on saving habits, our analysis revealed that this was not the case. The non-significant moderating effect of foreseeable expenses suggests that the fundamental strategies of setting long-term savings goals and establishing a robust financial safety net are important to enhancing saving behaviors regardless of specific anticipated future expenses. Financial professionals should prioritize helping clients establish a comprehensive financial safety net and clear savings goals, which have demonstrated strong associations with improved saving habits. While foreseeable expenses did not show a significant moderating effect in our study, they should not be completely disregarded in financial planning, as they can still play a critical role in personal financial management, according to Hogarth and Anguelov (2003). However, our results show that financial professionals should focus on the broader and more consistent impact of strategic financial planning practices that help clients navigate through their financial journey with or without specific foreseeable expenses. This could include strategies such as goal-based budgeting and emergency fund management to ensure financial stability regardless of anticipated or unexpected expenses.

The BLCH model, which underscores the integration of psychological factors like self-control and mental accounting into financial decision-making, is supported by our findings. Our study shows that long-term savings goals significantly mediate the relationship between a financial safety net and saving habits, supporting the BLCH model’s assertion that behavioral factors are pivotal in financial decision-making.

While foreseeable expenses did not emerge as a significant moderator in our study, they remain an important consideration in financial planning. This aspect calls for a nuanced understanding of the BLCH model, where the non-significant moderating effect of foreseeable expenses on savings goals’ effectiveness highlights the complexity of financial behavior and the potential for individual variations in response to different financial planning strategies. This observation invites a broader application of the BLCH model to accommodate the diversity in individual financial behavior and the varying impact of psychological factors across different financial contexts. These findings underscore the need for expert financial guidance to tailor financial strategies that account for individual variations in financial behaviors. Tailored strategies would be adjusted to reflect individual consumption, savings, and risk preferences.

8. Limitations and Future Research

Our study, while extensive, is not without its limitations. Primarily, the use of cross-sectional data restricts our ability to infer causality. This limitation is inherent in this study’s design, which captures data at a single point in time, thus precluding the establishment of a temporal sequence necessary for causal conclusions. Additionally, our findings may not be fully generalizable beyond the sampled demographic, limiting their applicability to different cultural or economic contexts. Such constraints highlight the potential for variation in saving behaviors across diverse environments that our study could not address. Furthermore, the scope of our moderated mediation model did not encompass all potential moderating variables, which may influence the relationships explored in our research.

To address these limitations and broaden the understanding of saving behaviors, future research could adopt different methodological approaches. Experimental designs could be utilized to test the efficacy of specific financial planning interventions, allowing for the establishment of causality through controlled manipulation of variables. Employing longitudinal data in future studies would significantly enhance our ability to ascertain causal relationships, providing a temporal dimension that allows for observing changes and developments over time. Considering that the dataset utilized in this study was collected in 2022, directly after the COVID-19 pandemic, future research could benefit from assessing the proposed conceptual models across diverse economic conditions. Future studies might also consider expanding this study by including diverse cultural and economic contexts to provide a richer, more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics at play. Moreover, incorporating qualitative research methods would offer deeper insights into personal financial decision-making processes, revealing individuals’ subjective experiences and motivations.

9. Conclusions

The findings from our research reaffirm the critical importance of cultivating good saving habits for ensuring financial stability and future preparedness. These habits are instrumental in influencing long-term financial outcomes, such as retirement preparedness and the adequacy of emergency funds. Our analysis demonstrates that setting specific, long-term savings goals and maintaining a robust financial safety net are essential strategies that significantly enhance saving behaviors. This relationship holds true across different financial and demographic contexts, highlighting the important benefits of structured and goal-oriented saving practices. Thus, the extensive use of these strategies can enhance the financial resilience of households.

Financial planners play a pivotal role in this financial ecosystem. They are tasked with guiding clients to set clear and attainable savings goals, which our findings suggest are foundational to developing strong saving habits. Planners also have a crucial role in educating clients about effective financial strategies, including the principles of mental accounting, which helps in setting aside funds for specific financial goals. Moreover, by assisting clients in building and maintaining emergency funds, planners can help their clients be better prepared to handle unforeseen financial challenges, thereby securing their financial future and contributing to overall financial resilience and stability. By doing so, financial planners can assist in creating a stronger economic future for all.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.O., M.J. and Y.Z.; methodology, Y.Z.; software, C.O. and Y.Z.; validation, C.O., M.J. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, C.O. and Y.Z.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.O., M.J., Y.Z. and K.N. writing—review and editing, C.O., M.J. and Y.Z.; visualization, C.O., M.J. and Y.Z; supervision, C.O.; project administration, C.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data underpinning the analyses presented in this manuscript were derived from publicly available sources and proprietary datasets, which are detailed within this manuscript. The primary dataset utilized, the 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), is publicly accessible via the Federal Reserve’s website, enabling interested researchers to replicate this study’s findings or extend the research in related areas.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- Saving HabitOver the past year, would you say that your (family’s) spending exceeded your (family’s) income, that it was about the same as your income, or that you spent less than your income?(Spending should not include any investments you have made.)IF DEBTS ARE BEING REPAID ON NET, TREAT THIS AS SPENDINGLESS THAN INCOME.1. *SPENDING EXCEEDED INCOME2. *SPENDING SAME AS INCOME3. *SPENDING WAS LESS THAN INCOME*/Measurement of Savings Goal in the SCFThe long-term savings goals are coded if household reasons for saving are 1, 2, 3, 6, 11, 12, 22, 26, 32 and 93.The code was based on the following question:People have different reasons for saving, even though they may not be saving all the time. What are your most important reasons for saving?1. Children’s education; education of grandchildren2. Own education; spouse/partner’s education;education—not known for whom3. “For the children/family”, n.f.s.; “to help thekids out”; estate5. Wedding, Bar Mitzvah, and other ceremonies(except 17)6. To have children/a family9. To move (except 11)11. Buying own house (code “summer cottage” in 12)12. Purchase of cottage or second home for own use13. Buy a car, boat, or other vehicle14. Home improvements/repairs15. To travel; take vacations; take other time off16. Buy durable household goods, appliances, homefurnishings; hobby and recreational items; forother purchases not codable above or notfurther specified; “buy things when we need/want them”; special occasions17. Burial/funeral expenses18. Charitable or religious contributions20. “To enjoy life”21. Buying (investing in) own business/farm; equipmentfor business/farm22. Retirement/old age23. Reserves in case of unemployment24. In case of illness, medical/dental expenses25. Emergencies; “rainy days”; other unexpected needs;for “security” and independence26. Investments reasons (to earn interest, to bediversified, to buy other forms of assets)27. To meet contractual commitments (debt repayment,insurance, taxes, etc.) to pay off house28. “To get ahead”; to advance standard of living29. Ordinary living expenses/bills30. Pay taxes31. No particular reason (except 90, 91, 92)32. “For the future”33. Like to save40. Do not wish to spend more41. To give gifts; "Christmas"90. Had extra income; saved because had the money leftover—no other purpose specified91. Wise/prudent thing to do; good discipline to save;habit92. Liquidity: to have cash available/on hand93. “Wealth preservation”; maintain lifestyle−1. Do not/cannot save; “have no money”−7. Other0. Inap. (/no further responses)Financial Safety NetIn an emergency, could you (or your {husband/wife/partner}) receive financial assistance of USD 3000 or more from any friends or relatives who do not live with you?1. *YES5. *NOForeseeable expensesIn the next five to ten years, are there any foreseeable major expenses that you (and your family) expect to have to pay for (yourself/yourselves), such as educational expenses, purchase of a new home, health care costs, support for other family members, or anything else?1. *YES5. *NOFinancial literacy variablesSubjective financial literacySome people are very knowledgeable about personal finances, while othersare less knowledgeable about personal finances. On a scale from zero to ten, where zero is not at all knowledgeable about personal finance and ten is very knowledgeable about personal finance, what number would you (and your {husband/wife/partner}) be on the scale?−1. *NOT AT ALL KNOWLEDGEABLE ABOUT PERSONAL FINANCE1.2.3.4.5.6.7.8.9.10. *VERY KNOWLEDGEABLE ABOUT PERSONAL FINANCEObjective financial literacyStockDo you think that the following statement is true or false: buying a single company’s stock usually provides a safer return than a stock mutual fund?1. *TRUE5. *FALSE−2. Do not know−3. Refused*/Savings interestSuppose you had USD 100 in a savings account, and the interest rate was 2% per year. After 5 years, how much do you think you would have in the account if you left the money to grow: more than USD 102, exactly USD 102, or less than USD 102?1. *MORE THAN USD 1023. *EXACTLY USD 1025. *LESS THAN USD 102−2. Do not know−3. Refused*/InflationImagine that the interest rate on your savings account was 1% per year, and inflation was 2% per year. After 1 year, would you be able to buy more than today, exactly the same as today, or less than today with the money in this account?1. *MORE THAN TODAY3. *EXACTLY THE SAME AS TODAY5. *LESS THAN TODAY−2. Do not know−3. Refused*/

Note

| 1 | Subjective financial knowledge responses ranged from 1 to 7: “On a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 means very low and 7 means very high, how would you assess your overall financial knowledge?” (Federal Reserve Board, 2023). Objective financial knowledge was computed based on respondents’ correct answers to three financial knowledge-related questions. The scores ranged from 0 (incorrect answers to all seven questions) to 3 (correct answers to all three financial knowledge questions) (Federal Reserve Board, 2023). The financial knowledge questions are described in Appendix A). |

References

- Abdelrahman, H., & Oliveira, L. E. (2023). The rise and fall of pandemic excess savings (FRBSF economic letter). Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Available online: https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2023/may/rise-and-fall-of-pandemic-excess-savings/ (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Aladangady, A., Cho, D., Feiveson, L., & Pinto, E. (2022). Excess savings during the COVID-19 pandemic (FEDS Notes). Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asebedo, S. D., Wilmarth, M. J., Seay, M. C., Archuleta, K., Brase, G. L., & MacDonald, M. (2019). Personality and saving behavior among older adults. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 53(2), 488–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialowolski, P., Xiao, J. J., & Weziak-Bialowolska, D. (2024). Do all savings matter equally? Saving types and emotional well-being among older adults: Evidence from panel data. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 45(1), 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricker, J., Dettling, L. J., Henriques, A., Hsu, J. W., Jacobs, L., Moore, K. B., Pack, S., Sabelhaus, J., Thompson, J., & Windle, R. A. (2017). Changes in US family finances from 2013 to 2016: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 103, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Brounen, D., Koedijk, K. G., & Pownall, R. A. (2016). Household financial planning and savings behavior. Journal of International Money and Finance 69, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M., & Lusardi, A. (1996). Household saving: Micro theories and micro facts. Journal of Economic Literature, 34(4), 1797–1855. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, I., & Svec, J. (2023). Household savings and present bias among Chinese couples: A household bargaining approach. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 57(1), 648–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S. H., Loibl, C., & Geistfeld, L. (2014). Motivation for emergency and retirement saving: An examination of regulatory focus theory. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(6), 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb-Clark, D. A., Kassenboehmer, S. C., & Sinning, M. G. (2016). Locus of control and savings. Journal of Banking and Finance, 73, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J. M., & Gjertson, L. (2013). Emergency savings for low-income consumers. Focus, 30(1), 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Copur, Z., & Gutter, M. S. (2019). Economic, sociological, and psychological factors of the saving behavior: Turkey case. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(2), 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croy, G., Gerrans, P., & Speelman, C. (2010). The role and relevance of domain knowledge, perceptions of planning importance, and risk tolerance in predicting savings intentions. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31(6), 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Reserve Board. (2023). Survey of Consumer Finances (2022). Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scfindex.htm (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Fisher, P. J., & Anong, S. (2012). Relationship of saving motives to saving habits. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 23(1), 63–79. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2222006 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Fisher, P. J., Hayhoe, C. R., & Lown, J. M. (2015). Gender differences in saving behaviors among low-to moderate-income households. Financial Services Review, 24(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, A., & Rossi, A. G. (2024). Goal setting and saving in the FinTech era. The Journal of Finance, 79(3), 1931–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S. D., Kim, K. T., & Lindamood, S. (2018). Behind the numbers: Understanding the survey of consumer finances. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 29(2), 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S. D., & Lee, J. M. (2015). Savings goals and financial behavior in young adults. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 26(2), 129–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hershfield, H. E., Shu, S., & Benartzi, S. (2020). Temporal reframing and participation in a savings program: A field experiment. Marketing Science, 39(6), 1039–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, J. M., & Anguelov, C. (2003). Can the poor save? Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 14(1), 1–18. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2265627 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Hogarth, J. M., Anguelov, C. E., & Lee, J. (2005). Who has a bank account? Exploring changes over time, 1989–2001. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 26, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennickell, A., & Shack-Marquez, J. (1992). Changes in family finances from 1983 to 1989: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 78, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G. J., & Hanna, S. D. (2017). Do self-control measures affect saving behavior? Journal of Personal Finance, 16(2), 1–20. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3000139 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Liu, F., Yilmazer, T., Loibl, C., & Montalto, C. (2019). Professional financial advice, self-control, and saving behavior. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 43, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A. (2008). Household saving behavior: The role of financial literacy, information, and financial education programs (No. w13824). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, K. D., & Hill, R. P. (2015). Saving and well-being at the base of the pyramid: Implications for transformative financial services delivery. Journal of Service Research, 18(3), 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, F., & Brumberg, R. (1954). Utility analysis and the consumption function: An interpretation of cross-section data. In K. Kurihara (Ed.), Post Keynesian economics (pp. 388–446). Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montmarquette, C., & Viennot-Briot, N. (2015). The value of financial advice. Annals of Economics and Finance, 16(1), 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, C., Crandall, T., & Chatterjee, S. (2025). The Impact of the COVID-19 Income Shock on Debt Management: A Mediation Analysis. Financial Services Review, 33(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, C., Hanna, S. D., & Kim, K. T. (2019). Are Asian households in the US more likely than other households to help children with college costs? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(3), 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rha, J., Montalto, C. P., & Hanna, S. D. (2006). The effect of self-control mechanisms on household saving behavior. Financial Counseling and Planning, 17(2), 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Shefrin, H. M., & Thaler, R. H. (1988). The behavioral life-cycle hypothesis. Economic Inquiry, 26(4), 609–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefrin, H. M., & Thaler, R. H. (1992). Mental accounting, saving, and self-control. Choice over Time, 287–330. [Google Scholar]

- Shefrin, H. M., & Thaler, R. H. (2004). Mental accounting, saving, and self-control. Advances in Behavioral Economics, 395–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S., Kim, H., & Heath, C. J. (2019). Narrow framing and retirement savings decisions. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 53(3), 975–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, L., Sun, L., & Geyfman, V. (2021). An assessment of the effects of mental accounting on overspending behaviour: An empirical study. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(2), 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2024). Personal saving rate. Available online: https://www.bea.gov/data/income-saving/personal-saving-rate (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Ülkümen, G., & Cheema, A. (2011). Framing goals to influence personal savings: The role of specificity and construal level. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(6), 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K. J., Ouyang, C., Machiz, I., McCoy, M., & Qi, J. (2022). An application of financial resilience to retirement planning by racial/ethnic status. The Journal of Retirement, 9(4), 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchester, D. D., Huston, S. J., & Finke, M. S. (2011). Investor prudence and the role of financial advice. Journal of Financial Service Professionals, 65(4). [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, D. W., & Hanna, S. D. (2024). The relationship between self-control factors and household saving behavior. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 35(3), 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuh, Y., & Hanna, S. D. (2010). Which households think they save? Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(1), 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinman, J. (2004). Why use debit instead of credit? Consumer choice in a trillion-dollar market. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).