Abstract

This paper investigates whether trade frictions, in the form of exchange controls, are among the main obstacles preventing the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) hypothesis from being valid among trading nations. It specifically looks at whether exchange controls—a type of trade friction—hinder PPP’s applicability in the relationship between an emerging economy, South Africa, and its major trading partners, classified by their use of exchange control regulations. The methodology used to test the PPP hypothesis includes nonlinearity through quantile unit root tests and quantile cointegration, designed to capture the varied economic conditions across trading nations. The empirical findings indicate that trade frictions may not necessarily obstruct the validity of the PPP hypothesis. Moreover, the weak form of the PPP hypothesis predominantly appears at the extreme quantiles of the real exchange rate among trading nations, especially the lower quantile, which is associated with the real exchange rate depreciation of the South African economy. This insight is significant for both policymakers and investors.

1. Introduction

Numerous studies have been dedicated to exploring the validity of the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) hypothesis in relation to both bilateral and multilateral exchange rates (see Alba & Papell, 2007; Moatsos & Lazopoulos, 2021; Olaniran & Ismail, 2023). The core premise of the PPP hypothesis is that the exchange rate between two countries should ideally mirror the difference in their respective consumer price indices, thereby reflecting the price differential between them. In essence, PPP suggests that a standardized basket of goods should cost the same in both countries when the exchange rate is factored in.

This concept gains further complexity and nuance in the work of Driver and Westaway (2013), who posit that PPP can only be considered inherently valid if the Law of One Price (LOOP) is consistently applied under specific circumstances. These conditions include uniform consumer preferences across different countries, resulting in a standardized basket of goods; the ability to trade all goods and services freely; and the identical production of goods in each country. The absence of any of these prerequisites may lead to the failure of PPP, even if the LOOP is observed in practice.

The implications of the PPP hypothesis extend beyond theoretical considerations. It serves as a crucial tool for evaluating the extent of financial and economic integration between countries on a bilateral or multilateral scale. This aspect of PPP has been further explored and elaborated in studies such as those by Taguchi (2010), Yoon and Jei (2020), and Nagayasu (2021). These investigations underscore the relevance of PPP as more than just a theoretical model; it is a practical measure that reflects the interconnectedness and economic congruence of global economies.

Results from testing the PPP (Purchasing Power Parity) hypothesis have been contentious, with some studies supporting the hypothesis and others opposing it (see Robertson et al., 2014; Yoon & Jei, 2020; Moatsos & Lazopoulos, 2021; Nagayasu, 2021). This disparity in PPP test results is frequently ascribed to the deployment of inappropriate statistical and econometric methods. For instance, Taylor and Taylor (2004) emphasized that empirical studies relying on traditional unit root and cointegration tests often yield unreliable outcomes.

There is an agreement among scholars that the test of the PPP hypothesis is carried out by using two general types of tests, one involving the stationarity of the real exchange rate and another utilizing the cointegration relationship of the nominal exchange rate and price difference (Chang, 2002; Bonga-Bonga, 2011; Moatsos & Lazopoulos, 2021). However, a disagreement resides in the appropriate type of stationarity or cointegration technique to be used. The traditional stationarity and cointegration techniques developed by Granger (1984), Engle and Granger (1987), and Johansen and Juselius (1990) are usually associated with these tests. However, studies have challenged these techniques arguing that the mean-reverting process related to the PPP theory is nonlinear rather than linear (see Chang, 2002; Lyon & Olmo, 2017).

On a theoretical basis, the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) hypothesis is grounded in the idea that, under ideal conditions, identical goods should sell for the same price in different markets when prices are expressed in a common currency. This premise largely depends on the assumption of a free flow of goods and services among trading partners. In regions where market integration is high and trade barriers are minimal—as evidenced by studies such as Yildirim (2017)—the PPP tends to hold, suggesting that closer economic ties facilitate the convergence of prices. However, empirical evidence also indicates that the PPP hypothesis does not uniformly apply across all trading relationships. For example, Tiwari and Shahbaz (2014) demonstrate that in the case of India, the PPP relationship breaks down with several of its major trading partners. The authors argue that this divergence can be attributed to significant barriers affecting the trade of intermediate goods. Such obstacles—ranging from tariffs and non-tariff measures to regulatory and logistical challenges—introduce friction that disrupts the efficient transmission of price signals across borders. This finding by Tiwari and Shahbaz (2014) raises an important question: to what extent does trade friction undermine the validity of the PPP theory? Despite its potential significance, the role of trade friction in either hindering or supporting the PPP framework remains underexplored in the academic literature. It is in this context that this paper seeks to fill this gap by assessing whether trade friction could enhance or hinder the applicability of PPP in different economic settings.

Trade frictions can arise in various forms, such as quotas or exchange rate controls (Alvarez & Braun, 2006; Wei & Zhang, 2007; Tamru et al., 2021). For instance, Wei and Zhang (2007) demonstrate that exchange controls adversely affect trade by increasing the costs associated with intensified border inspections and other measures designed to prevent evasion. These trade frictions may obstruct the functioning of the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) theory, depending on the trade volume. Specifically, the PPP hypothesis relies on arbitrage opportunities to facilitate price equalization across countries. However, frictions like exchange controls, such as restrictions on currency convertibility or trade barriers, disrupt the natural flow of goods and capital. This disruption limits arbitrage opportunities, thereby hindering the convergence of price differentials as predicted by the PPP theory.

While exchange rate controls, viewed as a form of trade friction or barrier, may impede the validity of the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) hypothesis among trading partners, no study has yet explored this theoretical dimension in evaluating the PPP hypothesis. This paper aims to address this gap by investigating the extent to which exchange controls influence the PPP hypothesis among trading partners. This paper contributes to the literature in three significant ways. First, it evaluates the validity of the PPP hypothesis among trading partners that implement exchange controls as a trade friction mechanism, making a distinction between cases where one or both partners apply exchange controls. Second, it incorporates economic conditions related to the distribution of exchange rates and price levels among trading partners. This analysis accounts for nonlinearity by employing quantile unit root tests and cointegration methods, enabling an assessment of how different market conditions affect the validity of the PPP hypothesis. Third, this study differentiates between the weak form of PPP—evaluated through the stationarity of the real exchange rate using the quantile unit root approach—and the strong form of PPP, which posits a one-to-one relationship between exchange rates and relative prices. The strong form is tested using the quantile cointegration method, drawing on the frameworks of Pedroni (2001) and Robertson et al. (2014).

This paper focuses on South Africa and its trading partners, which are categorized based on their adherence to exchange control regulations. Notably, South Africa introduced exchange controls during the Apartheid era as a measure to curtail massive capital outflows, a consequence of the international economic and financial sanctions it faced at the time. Although this regulation has been gradually relaxed, it remains in place to some extent. Among South Africa’s trading partners, Morocco, Sri Lanka, Egypt, Indonesia, and China still maintain exchange control regulations. Conversely, the Czech Republic, Botswana, the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom do not enforce such controls1.

Choosing South Africa as an example of an African emerging economy in a study examining trade impacts with its partners is well founded for several reasons. Firstly, South Africa ranks among Africa’s largest and most advanced economies, making it an ideal proxy for the economic prospects and significance of African emerging markets in the international trade sphere (Patra & Muchie, 2019; Mishra et al., 2023). Secondly, its economy is more diverse than many of its African counterparts, boasting strengths in mining, manufacturing, and services. Such diversity positions it as a fitting representative of the range of economic activities and trade dynamics typical of emerging African economies (Klein & Wöcke, 2007; Ashman & Fine, 2013). Lastly, South Africa’s extensive trade networks encompass various countries and regions, including fellow African states, the European Union, China, and the USA (Scholvin & Draper, 2012). Investigating these trade relations can provide crucial insights into the central research question addressed in this paper.

2. Literature Review

A substantial body of research has focused on examining the validity of the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) hypothesis, investigating its applicability across both bilateral and multilateral exchange rate contexts. These studies aim mainly to determine whether exchange rates and relative price levels between countries align in a manner consistent with the theoretical underpinnings of the PPP. For example, Munir and Kok (2015) test the purchasing power parity (PPP) hypothesis for ASEAN-5 countries using panel unit root and cointegration tests. The results of the empirical analysis show mixed evidence for PPP: tests that ignore cross-country dependence reject PPP, while those accounting for dependence support it only after the 1997 financial crisis. Strong evidence for PPP emerges from cointegration tests that allow for structural breaks and cross-sectional dependence. The identified structural breaks align with macroeconomic shocks and institutional changes, offering valuable policy insights. Shim et al. (2016) assess whether the relative purchasing power parity (PPP) hypothesis holds for the Korean won–US dollar and Korean won–Japanese yen markets by using inflation proxies derived from stock market returns. The authors find that relative PPP does not hold over the full sample but holds for the won–US dollar market after excluding the Asian Financial Crisis period. The findings suggest that exchange rate volatility during crises and other factors beyond inflation influence the won–yen exchange rate. Al-Gasaymeh (2015) tests the strong and weak forms of purchasing power parity (PPP) between Jordan and its major trading partners from the period 2000–2012. The author finds that the strong PPP fails as real exchange rates are non-stationary, indicating no long-term equilibrium. However, weak PPP holds, with cointegration observed between exchange rates and price levels. The author argues that these findings suggest that proportionality and symmetry restrictions may explain the empirical failure of strong PPP.

Many studies attribute the failure of the PPP hypothesis to the reliance on linear methods and recommend adopting nonlinear approaches instead. For example, Jiang et al. (2016) apply a nonlinear threshold unit root test to examine the validity of purchasing power parity (PPP) and real exchange rate (RER) convergence for ten Central Eastern European countries. The results show that the PPP holds for seven countries, with RERs exhibiting nonlinear mean reversion towards equilibrium based on Taylor rules. The findings suggest that monetary policies in these economies are strongly influenced by external factors, particularly from the United States, and that capital mobility, exchange rate efficiency, and monetary integration follow a nonlinear pattern. Xie et al. (2024) provide new evidence on purchasing power parity (PPP) in 18 countries by jointly testing the non-stationarity and nonlinearity of real effective exchange rates (REERs). The findings of the study reveal that REERs exhibit nonlinearity, with stationarity dependent on the size of disequilibrium, linked to transaction costs. The exponential smooth transition autoregressive model best captures size nonlinearity. Additionally, the authors show that asymmetric adjustment, driven by price stickiness, is crucial for validating PPP when using a threshold autoregressive model. Yoon and Jei (2020) analyze the effects of NAFTA on Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) among the United States, Canada, and Mexico using a time-varying cointegration model. The findings reveal that the PPP validity fluctuates over time, with the consumer price index (CPI)-based PPP being more volatile than the producer price index (PPI)-based PPP, emphasizing the need for prioritizing consumption sector stabilization. Additionally, comparing PPP with Uncovered Interest Rate Parity (UIRP), the authors conclude that PPP is more reliable for evaluating long-term exchange rate movements. De Villiers and Phiri (2022) address the empirical inconsistencies in the purchasing power parity (PPP) hypothesis by using the fractional frequency flexible Fourier form (FFFFF) unit root test. This method captures asymmetries and accounts for unknown structural breaks in real exchange rate data for 14 newly industrialized countries (NICs) from 1970 to 2018. By introducing a binary search method to optimize fractional frequencies, the authors find that all NICs’ real exchange rates are mean reverting when asymmetries and structural breaks are considered, though forms of asymmetries vary across countries. Policy implications from these findings are also explored. Chan et al. (2023) investigate the purchasing power parity (PPP) hypothesis between China and its five major trading partners: the European Union, the United States, Brazil, Japan, and Korea. The authors show that traditional unit root tests with structural breaks have largely failed to confirm PPP. In addition to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), a tradable goods price index is used by the authors to account for the Balassa–Samuelson effect. Applying the Fourier quantile unit root test, which accommodates potential structural breaks and non-Gaussian distributions, they provide strong evidence supporting PPP between China and these trading partners.

Still accounting for the asymmetry in testing for the PPP hypothesis, Muto and Saiki (2024) assess how the exchange rates of the U.S. dollar with the euro and Japanese yen synchronize based on purchasing power parity. Using a Hilbert transform-based analysis, the authors find that these currencies are highly synchronized most of the time, supporting the idea of PPP. However, during periods marked by asymmetric economic events, such as the U.S. real estate bubble, this synchronization weakens. Jie and Liu (2024) develop a market-based price index that accounts for price regulation and uses it alongside the parallel market exchange rate to test the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) in China from 1952 to 2019. While official data offer weak support for PPP, no evidence against PPP is found when using the parallel market measures. Additionally, the real exchange rate of the RMB adjusts much faster—with a half-life of about one year—than the commonly estimated 3–5 years.

While previous studies have focused on testing the purchasing power parity (PPP) hypothesis, highlighting the significance of nonlinearity and asymmetry in its validation, none, to the best of our knowledge, have explicitly considered the role of exchange controls as a critical factor in trade friction and restrictions. Exchange controls, which regulate the flow of foreign exchange and influence the convertibility of currencies, are a vital element in determining the dynamics of international trade and price adjustments. Ignoring these controls may overlook a significant source of possible deviations from PPP. In this context, this paper examines the validity of the PPP hypothesis among trading partners that use exchange controls as a mechanism for trade friction, distinguishing between scenarios where exchange controls are implemented by one or both partners.

3. Methodology

The PPP hypothesis states that the nominal exchange rate between two countries should be equal to their relative prices. This implies

with being the nominal exchange rate (the domestic price of foreign currency), the domestic price level, and the foreign price level. When the natural logarithm is taken, Equation (1) is transformed into

The econometric model of Equation (2) is expressed as

with being the error term. The linear combination of Equation (3) yields

In Equation (4), denotes the real exchange rate, , especially when is unity. It is in that context that the test of the weak form of PPP relies on the stationarity of , while the strong form goes further by testing the null hypothesis of . It is worth noting that in a bivariate model, as expressed in Equation (4), the stationarity of implies a cointegrating relationship between and .

To test for the weak form of PPP within the quantile methodology, the quantile unit root test of Koenker and Xiao (2004) is considered. The conditional quantile autoregression model is given by

with being the conditional quantile of for the defined quantile level and the error term. The solution for is obtained using quantile regression. The null hypothesis of unit root conditional on the quantile level is then given by

with a t-ratio statistic defined by

where and are the probability and cumulative density functions of , is the vector of lagged real exchange rates used and is the projection matrix onto the space orthogonal to . The t-ratio statistic is estimated, and its critical values are found using a bootstrap approach outlined in (Koenker & Xiao, 2004).

To test for the strong form of PPP within the quantile methodology, the quantile cointegration regression framework of (Xiao, 2009) is considered. The model takes the form

where is the price difference and refers to information known prior to time t. The parameters are solved using quantile regression and the null hypothesis conditional on the quantile level is of the form

with test statistic

where , , and is the long-run variance of . The critical values are obtained through a bootstrap method. These results will, however, be displayed visually with confidence intervals for . The strong form PPP hypothesis holds if the null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected and .

4. Data

This paper utilizes monthly data spanning from January 1980 to July 20202. The selected sample encompasses significant epochs, capturing both tranquil and tumultuous periods in the global economy that can influence international trade. Nominal exchange rates concerning the South African currency, the rand, as well as consumer price indices were sourced from the South African Reserve Bank statistics and the International Financial Statistics of the International Monetary Fund.

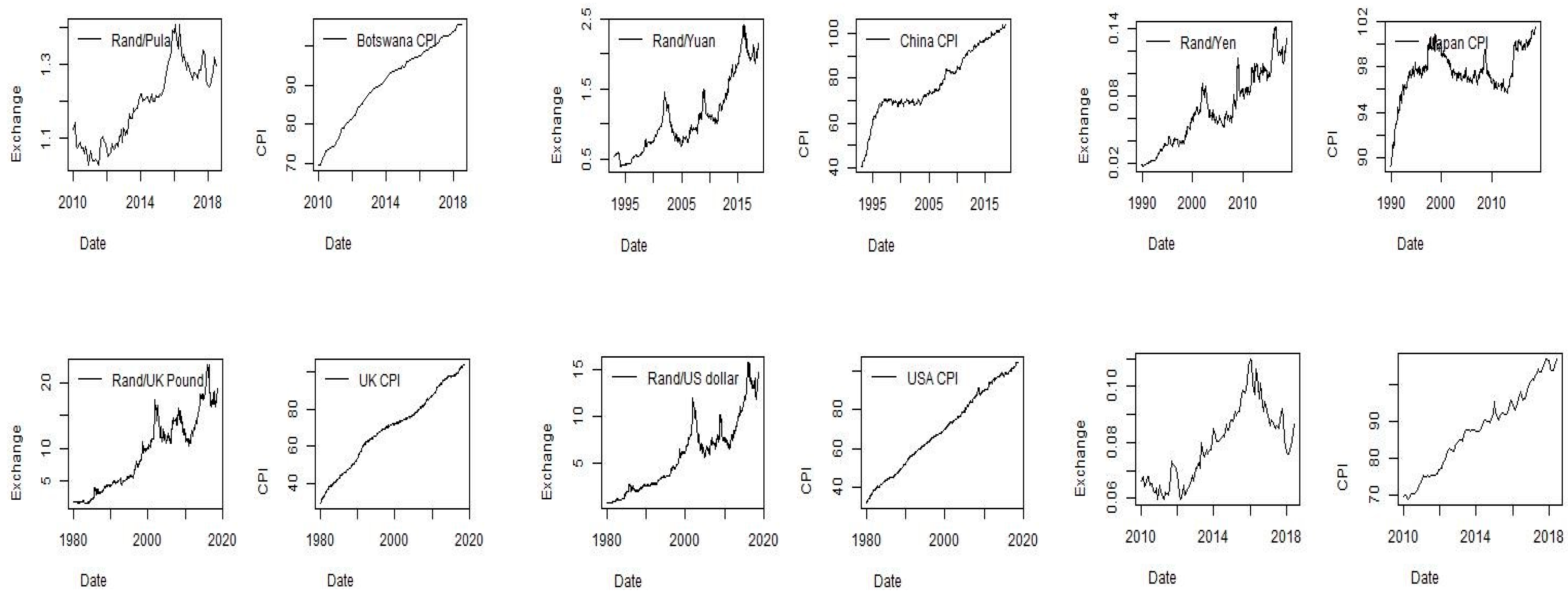

Figure 1 presents the exchange rates and consumer price indices for South Africa’s trading partners. Table A2 in Appendix A lists these key trading partners, based on COMTRADE statistics, along with the descriptive statistics of their exchange rates. A notable feature across the data, as illustrated in Figure 1, is the pronounced volatility of exchange rates during pivotal financial and economic crises, specifically the dot.com crisis of 2000, the global financial crisis of 2008, and the COVID-19 pandemic. CPI data indicate a consistent upward trend, suggesting that inflationary episodes are a predominant characteristic in many countries’ price structures.

Figure 1.

Exchange rates and CPI of selected countries.

The exchange rate trajectory between the South African rand and currencies of developed trading partners exhibits a marked similarity. These rates tend to spike during global financial crises and recede during more stable periods. Various factors may contribute to the parallel trends observed in exchange rates between South Africa and several developed economies. These factors encompass global economic cycles, investor sentiment, trade connections, and financial contagion.

In terms of the global economic cycle, it is crucial to highlight that a thriving global economy often sees investors gravitating towards higher yields in emerging markets, such as South Africa. In contrast, during global economic slumps or financial crises, capital flows reverse, moving away from emerging markets and gravitating towards the relative safety of developed economies. Such cyclical behaviors can lead to the South African rand (ZAR) mirroring movements against currencies of several developed nations (Frankel, 2010). A similar logic can be applied when discussing investor sentiment and financial contagion.

5. Empirical Results and Discussion

To examine whether the PPP hypothesis holds in its weak form between South Africa and its primary trading partners, we employ the quantile unit root tests on their real exchange rate, as delineated in Equation (5). The real exchange rate is constructed as = , which is expressed in a natural logarithm as , where is the natural logarithm of the nominal exchange rate between the South African rand and the currency of its trading partners and and are consumer price indices in South Africa and its trading partners, respectively.

We advocate for the quantile unit root test based on concerns surrounding the traditional unit root tests for the real exchange rate. Specifically, the results of the test based on the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) tests, reported in the Appendix A (Table A1), either yield inconclusive outcomes or fail to corroborate the stationarity of the real exchange rate. Additionally, the Jarque–Bera test results predominantly reject the null hypothesis of normality for the real exchange rates. Given these observations, we recommend the quantile unit root test as it better accounts for the asymmetrical behavior of the real exchange rate, a behavior underscored by the rejection of the standard normal distribution.

To account for possible asymmetry, the quantile unit root test is executed over the quantiles τ ∈ (0.1, 0.2, …, 0.9). We calculate the critical statistics for the test and the corresponding p-values using a bootstrap methodology, following the approach outlined in Koenker and Xiao (2004). Table 1 and Table 2 present the t-statistics and p-values for each quantile. These tables differentiate between South African trading partners based on whether they have exchange control regulations.

Table 1.

Quantile unit root test of real exchange rate: partners without exchange control regulation.

Table 2.

Quantile unit root test of real exchange rate: partners with exchange control regulation.

It is pivotal to underscore that, according to the tabulated results, the null hypothesis of a unit root (indicating the non-stationarity of the real exchange rate) is rejected at the 10%, 5%, and 1% significance levels if the corresponding p-values fall below 0.1, 0.05, and 0.01, respectively. Rejecting this null hypothesis points to the validity of the weak form of the PPP hypothesis for that particular quantile.

The findings presented in Table 1, concerning South Africa’s trading partners that do not implement exchange control regulations, indicate that the null hypothesis of a unit root is largely upheld across all countries at every quantile level, with Botswana being the sole exception. Specifically, for Botswana, this hypothesis is rejected at lower quantiles, notably at the 10% and 30% quantiles. Crucially, it should be emphasized that the lower quantile of the South African real exchange rate is representative of its depreciation. A real depreciation in currency can enhance a country’s trade competitiveness and furnish opportunities to ameliorate its terms of trade.

Table 2 displays the outcomes of the quantile unit root test of the real exchange rate between South Africa and its principal trading partners that impose exchange control regulations. The results reveal that the null hypothesis of a unit root is rejected for China at the 30%, 50%, 60%, and 70% quantiles. Furthermore, for Indonesia, the null hypothesis is rejected across all lower quantiles and the majority of the upper quantiles. However, there is no evidence to support the rejection of the null hypothesis of a unit root for the remaining countries that implement exchange control regulations.

From the insights derived from Table 1 and Table 2, several key observations emerge. First, predominantly, the weak form of the PPP hypothesis is evident at the extreme quantile of the real exchange rate, especially the lower quantile, which corresponds to when the South African real exchange rate depreciates. This phenomenon can be attributed to the idea that a real currency depreciation plays a pivotal role in rectifying potential disequilibria related to the PPP hypothesis (Bonga-Bonga, 2019). Essentially, beginning from a position of disequilibrium, if a real depreciation, subsequently leading to currency undervaluation, makes domestic goods more affordable for foreigners, it can drive up exports and taper off imports. This shift results in a trade surplus, exerting upward pressure on the currency, and can recalibrate the real exchange rate in alignment with the PPP. Second, the validation of the PPP hypothesis does not appear to be influenced by whether a country enforces an exchange control regulation. As an illustration, the PPP hypothesis stands true for both Botswana and Indonesia, despite the contrasting exchange control regulations they have in place. Lastly, the findings hint at the PPP hypothesis predominantly holding ground between South Africa and certain emerging market nations. In contrast, there is scant evidence to substantiate the validity of the PPP hypothesis between South Africa and the chosen developed economies for this paper.

As for why the PPP hypothesis is more prevalent between emerging markets than between developed and emerging economies, this fact may be explained by a combination of factors related to the similarities of the economic structures among emerging economies, the similarities between their responses to global shocks, and their dependence on natural resources. As for the similarity of economic structures being why PPP might hold between emerging economies, it is worth noting that emerging economies often have similar economic structures, face comparable challenges, and grow at comparable rates. As a result, different goods and services may have similar prices. Adding to this similarity of economic structure, the common responses of emerging economies to global shocks due to contagion synchronize their business cycle (see Teng et al., 2013; Bonga-Bonga, 2019); thus, most economic indicators display a common trend. On the dependence of most emerging economies on natural resources for their export revenues, the price dynamics of these resources can influence both economies similarly, affecting their exchange rates and prices.

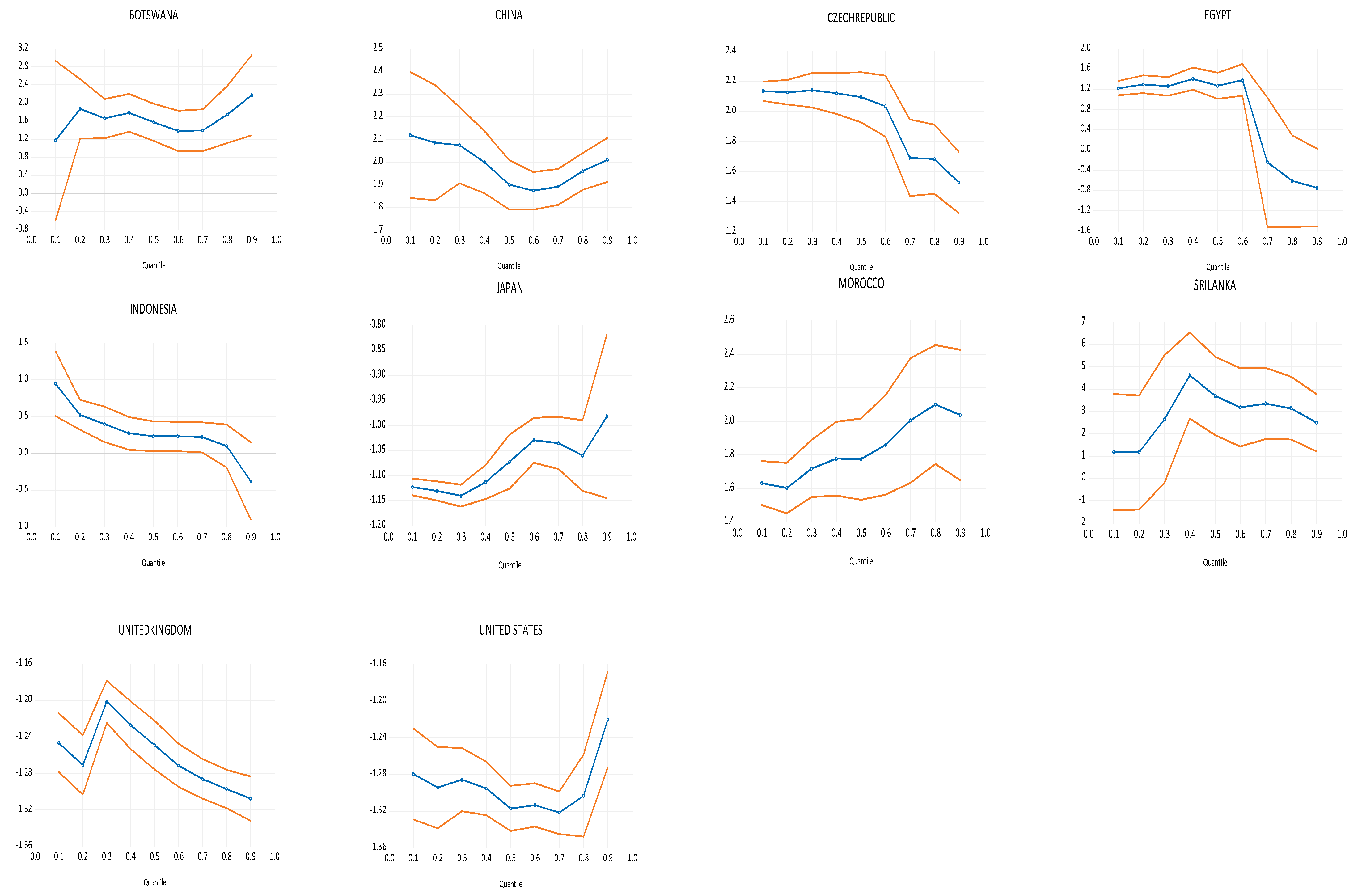

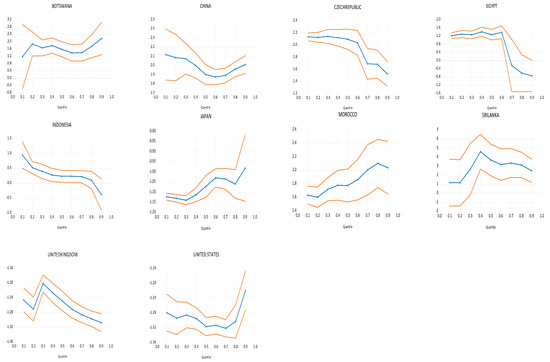

Regarding the strong form of the PPP hypothesis, we estimate the dynamic cointegrating vector based on Equation (7) and then evaluate if . In addition, we apply the test statistics as suggested in Equation (8) to confirm a cointegrating relationship at the quantile where . Figure 2 presents the dynamics of across the different quantiles. Its 99% confidence intervals are represented in red.

Figure 2.

Dynamics of cointegrating vectors across different quantiles. Orange: confidence interval. Blue: values.

When interpreting the results shown in Figure 2, several key points stand out concerning the strong form of the PPP hypothesis. First, the confidence interval must encompass the value of unity. Second, even if this interval contains the value of unity, it should not include the value of zero. Third, the null hypothesis of no cointegration should be rejected at the quantile that includes the value of unity. From Figure 23, we see that all three of these conditions are met for Indonesia at the 10% quantile, Botswana at 20%, and Sri Lanka at 10%.

These findings indicate that both the strong and weak forms of the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) hypothesis hold between South Africa and the emerging economies studied. This reinforces the idea that PPP is most valid among countries with similar economic structures and synchronized business cycles. In other words, even in the presence of trade frictions, if countries react similarly to global economic shocks due to parallel economic structures, the PPP is likely to remain intact.

A prime example is the relationship between Botswana and South Africa. Despite Botswana not imposing foreign exchange controls or restricting capital outflows through its financial institutions, our analysis demonstrates that the PPP hypothesis holds between the two nations. Both the weak and strong forms of the hypothesis are evident, particularly at the lower quantile of the real exchange rate distribution between their currencies. These outcomes highlight that structural economic alignment may be a critical factor in maintaining the validity of PPP, even when other market frictions exist.

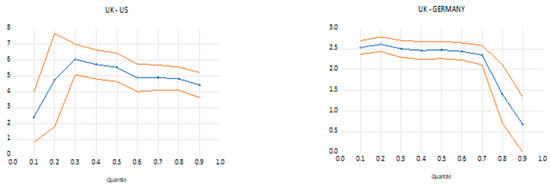

To determine whether the validity of the PPP hypothesis is more closely linked to the synchronization of business cycles between countries rather than merely the absence of trade frictions this paper examines its applicability among developed economies. Notably, evidence suggests that business cycles in developed economies tend to synchronize to a degree. Such synchronization is often credited to aspects like trade connections, financial integration, and parallel economic policies (Kose et al., 2008; Karadimitropoulou, 2018). However, it is essential to highlight that while synchronization exists, it is not absolute. There are occasions when the business cycles of two countries diverge. This very inconsistency underscores this paper’s rationale for using a time-varying approach linked to the quantile model to test the PPP hypothesis.

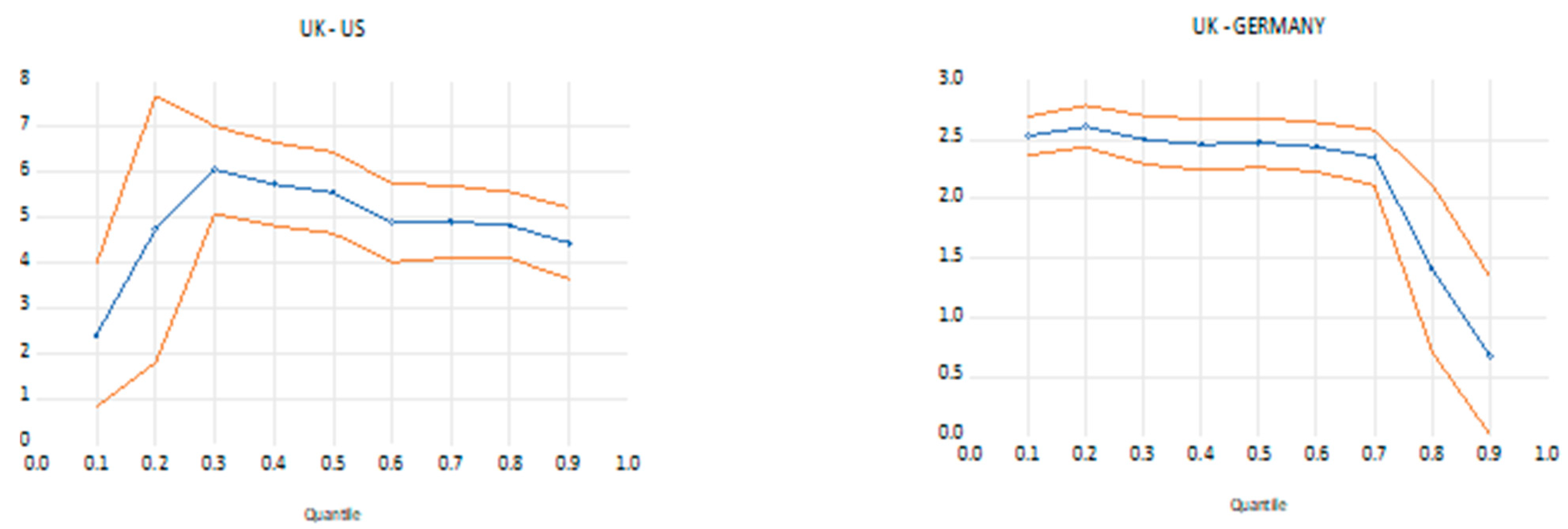

Figure 3 presents the outcomes of the strong form of the PPP hypothesis using quantile cointegration between the UK and US, as well as the UK and Germany. The findings indicate that the hypothesis is valid at extreme quantiles, specifically when one currency either appreciates or depreciates in relation to another.

Figure 3.

The dynamics of the cointegrating vectors across the different quantiles in developed economies. Blue: values. Orange: confidence interval.

It is essential to highlight that this paper’s findings underscore the importance of synchronized business cycles and similar economic structures between countries for the PPP hypothesis to hold. However, because business cycle synchronization is not perfect and does not persist indefinitely, quantile regression models serve as a valuable tool for determining when such synchronization takes place, and, thus, when the PPP hypothesis is valid. The results of this paper support the PPP hypothesis at the extreme quantile distributions. They may suggest that countries’ business cycles likely synchronize during these extreme quantiles, particularly when certain currencies appreciate or depreciate against others.

The rationale behind these findings may be linked to global imbalances and the resulting external adjustments. Global imbalances, such as sustained trade surpluses or deficits between countries, can lead to concerns about the sustainability of trade and financial flows and the synchronization of real business cycles among countries (Djigbenou-Kre & Park, 2016; Allegret et al., 2015). Studies show that one of the ways to adjust these imbalances is through the real exchange rate channel (Omoshoro-Jones & Bonga-Bonga, 2021; Bonga-Bonga, 2019; Schnatz, 2011).

Regarding the adjustment of global imbalances through the real exchange rate channel, Omoshoro-Jones and Bonga-Bonga (2021) demonstrated that in trade surplus countries, a rise in exports can lead to currency appreciation. As the currency appreciates, exports become costlier while imports become more affordable. Over time, this could diminish the trade surplus, with exports declining and imports increasing. Conversely, a trade deficit might exert downward pressure on a nation’s currency, leading to its depreciation, thus, boosting exports. These adjustments underscore that severe fluctuations in both nominal and real exchange rates—manifested in changes in extreme quantiles—are necessary for the synchronization of the business cycle and price equality between countries.

It is important to highlight that the aforementioned mechanism for global imbalances adjustment can result in exchange rate shifts. Within the framework of the PPP theory, these shifts aid in re-establishing the equilibrium concerning the relative price levels between nations.

6. Conclusions

This paper aimed to investigate whether trade frictions, primarily in the form of exchange controls, serve as a central barrier to the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) hypothesis among trading nations. The focus was on the relationship between an emerging economy, South Africa, and its major trading partners. These partners were categorized based on whether they implement exchange control regulations or not.

The methodology used incorporates nonlinearity, using quantile unit root tests and quantile cointegration, to accommodate the varying economic conditions between trading countries. Empirical evidence indicates that the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) hypothesis tends to hold more robustly between countries that share similar economic structures and exhibit synchronized business cycles. A prime example is the relationship between Botswana and South Africa. Despite Botswana not enforcing foreign exchange controls or imposing capital outflow restrictions through its financial institutions, the PPP hypothesis remains valid between these two nations. In fact, both the weak and strong forms of the hypothesis show consistency at the lower quantile of the real exchange rate distribution between their currencies. These findings support the findings of other studies that demonstrate that the PPP hypothesis does not uniformly apply across all trading relationships (see Tiwari & Shahbaz, 2014).

This observation leads to the intriguing possibility that trade frictions may not necessarily undermine the validity of the PPP hypothesis when countries have congruent economic structures and react similarly to global economic shocks. In such contexts, the commonality in economic behavior might offset the negative effects of trade barriers, thereby sustaining price convergence despite the presence of friction.

These insights carry significant policy implications, especially for investors and asset managers. The findings suggest that when devising investment and portfolio allocation strategies, greater emphasis should be placed on the alignment of economic structures rather than solely on differences in trade policies and monetary controls, such as exchange regulations. This strategic focus on structural congruence could provide a more stable and reliable framework for forecasting currency movements and ensuring market stability.

For future studies, we recommend an exploration of the PPP hypothesis under varied conditions, particularly focusing on time-frequency and frequency aspects. Specifically, it would be valuable to investigate whether the hypothesis remains valid when considering issues related to different time series frequencies with the use of Fourier transform. This includes an analysis of both short-term and long-term frequency patterns. For example, examining the PPP hypothesis in the context of short-term economic fluctuations versus long-term economic trends could provide insightful distinctions. Such an analysis could reveal how the PPP hypothesis behaves under varying temporal scales, potentially offering a more nuanced understanding of its applicability across different economic scenarios.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Unit root test and normality tests.

Table A1.

Unit root test and normality tests.

| ADF (t-Statistics) | KPSS (LM-Statistics) | Jarque-Bera Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SA/Botwsana | −1.5856 | 0.9302 *** | 2.62 |

| SA/China | −1.6376 | 1.4012 *** | 6.49 *** |

| SA/Czech | −2.2348 | 1.4716 *** | 18.9 *** |

| SA/Egypt | −1.8262 | 0.2594 | 6.0057 ** |

| SA/Indonesia | −3.8152 *** | 1.551 *** | 182.17 *** |

| SA/Morocco | −1.685 | 0.7626 *** | 2.822 *** |

| SA/Japan | 3.047 | 0.2833 | 2.3 |

| SA/Srilanka | −1.5742 | 0.9308 *** | 4.9247 * |

| SA/UK | −1.6591 | 2.522 *** | 42.2 *** |

| SA/US | −2.235 | 2.485 *** | 39.17 *** |

Note: ***, **, and * denote rejection at 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Null hypothesis of ADF is presence of unit root while null hypothesis of KPSS in that series are stationary.

Table A2.

Results of quantile cointegration test.

Table A2.

Results of quantile cointegration test.

| Country | Quantile | t-Statistics | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | 10% | −1.6191 *** | cointegration |

| Botswana | 10% | −0.134 * | cointegration |

| Sri Lanka | 20% | −0.199 * | cointegration |

*** and * denote rejection of null hypothesis of no cointegration at 1% and 10% level of significance, respectively.

Notes

| 1 | We selected South Africa’s key trading partners who either use exchange control or not. |

| 2 | It is worth noting that the starting sample period varies by country depending on data availability. This did not compromise this study as the test is conducted by country. Moreover, the selected sample encompasses both periods of relative calm and key economic crises, providing a robust framework for testing the PPP hypothesis under varying market conditions. |

| 3 | We tested the cointegrating relationship at the quantiles where and found the rejection of the null hypothesis of no cointegration. See results in Table A2. |

References

- Alba, J., & Papell, D. (2007). Purchasing power parity and country characteristics: Evidence from panel data tests. Journal of Development Economics, 83, 240–251. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Gasaymeh, A. (2015). Strong and weak form of purchasing power parity: The case of Jordan and its major trading partners. Journal of International Business and Economics, 3(1), 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Allegret, J. P., Mignon, V., & Sallenave, A. (2015). Oil price shocks and global imbalances: Lessons from a model with trade and financial interdependencies. Economic Modelling, 49, 232–247. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, R., & Braun, M. (2006). Trade liberalization, process distortions and resource allocations. Central Bank of Chile working paper no. 374.

- Ashman, S., & Fine, B. (2013). Neo-liberalism, varieties of capitalism, and the shifting contours of South Africa’s financial system. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 81(1), 144–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonga-Bonga, L. (2011). Testing for the purchasing power parity hypothesis in a small open economy: A VAR-X Approach. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 10(12), 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bonga-Bonga, L. (2019). Fiscal policy, monetary policy and external imbalances: Cross-country evidence from Africa’s three largest economies. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 28(2), 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K. S., Lai, J. T., & Liang, X. (2023). Testing the validity of purchasing power parity for China: Evidence from the Fourier quantile unit root test. Review of International Economics, 31(2), 464–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y. (2002). Nonlinear IV unit root tests in panels with cross-sectional dependency. Journal of Econometrics, 110(2), 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, D., & Phiri, A. (2022). Towards resolving the purchasing power parity (PPP) ‘Puzzle’ in newly industrialized countries (NIC’s). The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 31(2), 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Djigbenou-Kre, M. L., & Park, H. (2016). The effects of global liquidity on global imbalances. International Review of Economics & Finance, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Driver, R. L., & Westaway, P. F. (2013). Concepts of equilibrium exchange rates. In Exchange rates, capital flows and policy (pp. 98–148). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Engle, R. F., & Granger, C. W. (1987). Co-integration and error correction: Representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica, 55(2), 251–276. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, J. A. (2010). The natural resource curse: A survey. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper no. 15836.

- Granger, C. W. J. (1984). Some properties of time series data and their use in econometric model specification. Handbook of Econometrics, 2, 1023–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C., Jian, N., Liu, T. Y., & Su, C. W. (2016). Purchasing power parity and real exchange rate in Central Eastern European countries. International Review of Economics & Finance, 44, 349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Jie, H., & Liu, X. (2024). Price regulation, exchange rate regulation and the purchasing power parity: Empirical evidence from China. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 60(7), 1537–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, S., & Juselius, K. (1990). Maximum likelihood estimation and inference on cointegration—With applications to the demand for money. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 52(2), 169–210. [Google Scholar]

- Karadimitropoulou, A. (2018). Advanced economies and emerging markets: Dissecting the drivers of business cycle synchronization. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 93, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, S., & Wöcke, A. (2007). Emerging global contenders: The South African experience. Journal of International Management, 13(3), 319–337. [Google Scholar]

- Koenker, R., & Xiao, Z. (2004). Unit root quantile augoregression inference. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 99, 775–787. [Google Scholar]

- Kose, M. A., Otrok, C., & Whiteman, C. H. (2008). Understanding the evolution of world business cycles. Journal of International Economics, 75(1), 110–130. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, M., & Olmo, J. (2017). Does the PPP condition hold for oil-exporting countries? A quantile cointegration regression approach. International Journal of Finance and Economics, 23(2), 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A. K., Theertha, A., Amoncar, I. M., & RL, M. (2023). Equity market integration in emerging economies: A network visualization approach. Journal of Economic Studies, 50(4), 696–717. [Google Scholar]

- Moatsos, M., & Lazopoulos, A. (2021). Purchasing power parities and the Dollar-A-Day approach: An unstable relationship. Economics Letters, 206, 109974. [Google Scholar]

- Munir, Q., & Kok, S. C. (2015). Purchasing power parity of ASEAN-5 countries revisited: Heterogeneity, structural breaks and cross-sectional dependence. Global Economic Review, 44(1), 116–149. [Google Scholar]

- Muto, M., & Saiki, Y. (2024). Synchronization analysis between exchange rates on the basis of purchasing power parity using the Hilbert transform. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 74, 102191. [Google Scholar]

- Nagayasu, J. (2021). Causal and frequency analyses of purchasing power parity. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 71, 101287. [Google Scholar]

- Olaniran, S. F., & Ismail, M. T. (2023). Testing absolute purchasing power parity in West Africa using fractional cointegration panel approach. Scientific African, 20, e01615. [Google Scholar]

- Omoshoro-Jones, O. S., & Bonga-Bonga, L. (2021). Global imbalances, external adjustment and propagated shocks: An African perspective from a global VAR model. International Economics, 165, 186–203. [Google Scholar]

- Patra, S. K., & Muchie, M. (2019). Science and technological capability building in global south: Comparative study of India and South Africa. In Innovation, regional integration, and development in Africa: Rethinking theories, institutions, and policies (pp. 303–336). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Pedroni, P. (2001). Purchasing power parity tests in cointegrated panels. Review of Economics and Statistics, 83, 727–731. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R., Kumar, A., & Dutkowsky, D. (2014). Weak-form and strong-form purchasing power parity between the US and Mexico: A panel cointegration investigation. Journal of Macroeconomics, 42, 241–262. [Google Scholar]

- Schnatz, B. (2011). Global imbalances and the pretence of knowing fundamental equilibrium exchange rates. Pacific Economic Review, 16(5), 604–615. [Google Scholar]

- Scholvin, S., & Draper, P. (2012). The gateway to Africa? Geography and South Africa’s role as an economic hinge joint between Africa and the world. South African Journal of International Affairs, 19(3), 381–400. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, H., Kim, H., Kim, S., & Ryu, D. (2016). Testing the relative purchasing power parity hypothesis: The case of Korea. Applied Economics, 48(25), 2383–2395. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, H. (2010). Feasibility of Currency Unions in Asia-An Assessment Using Generalized Purchasing Power Parity. Public Policy Review, 6(5), 859–872. [Google Scholar]

- Tamru, S., Miten, B., & Swinnen, J. (2021). Trade, value chains and rent distribution with foreign exchange controls: Coffee export in Ethiopia. Agricultural Economics, 52(1), 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A. M., & Taylor, M. P. (2004). The Purchasing Power Parity Debate. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(4), 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, K. T., Yen, S. H., & Chua, S. Y. (2013). The synchronisation of ASEAN-5 stock markets with the growth rate cycles of selected emerging and developed economies. Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 7(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, A. K., & Shahbaz, M. (2014). Revisiting purchasing power parity for India using threshold cointegration and nonlinear unit root test. Economic Change and Restructuring, 47, 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S. J., & Zhang, Z. (2007). Collateral damage: Exchange controls and international trade. Journal of International Money and Finance, 26(5), 841–863. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z. (2009). Quantile cointegration regression. Journal of Econometrics, 150, 248–260. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z., Chen, S. W., & Hsieh, C. K. (2024). Testing PPP hypothesis under considerations of nonlinear and asymmetric adjustments: New international evidence. Empirica, 52(1), 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, D. (2017). Empirical investigation of purchasing power parity for Turkey: Evidence from recent nonlinear unit root tests. Central Bank Review, 17(2), 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J. C., & Jei, S. Y. (2020). Purchasing power parity vs. uncovered interest rate parity for NAFTA countries: The value of incorporating time-varying parameter model. Economic Modelling, 90, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).