Abstract

The pandemic caused by the coronavirus continues to test barriers around the world. In this sense, the tourism industry has become the sector most affected by the crisis with more than 900 million euros in losses. Recovery will require a great effort, especially in countries where the sector accounts for a large share of the economy and employment. This study analyzes the perceptions and proposals of the residents of the autonomous community of Andalusia. A total of 658 surveys were conducted during the closure. A quantitative and qualitative thematic analysis was carried out using SPSS and NVivo Pro programs. The findings provide significant insights into the economic recovery of society after the pandemic. The Andalusians have opted for local tourism so that the residents become the consumers of the tourist products of their territory. The deployment of new technologies and marketing campaigns should provide the basic strategies for structural changes and innovations. The residents demand a united Europe and disagree with the statements of some political leaders. The conclusions have practical and theoretical implications for tourist destinations.

1. Introduction

Tourism is one of the most important economic activities in developed economies. However, it is more vulnerable than other sectors to critical situations (Baum and Hai 2020; Laws et al. 1998; Gössling et al. 2020; Ma et al. 2020; Ritchie et al. 2020). While the world is trying to overcome the pandemic, they are facing the consequences of the war between Ukraine and Russia. The tourism sector needs a calm environment and depends on international politics, transportation, gasoline, economic cycles (Nundy et al. 2021; Khan et al. 2020), and the success of marketing campaigns (Kaur 2017).

Over the past decades, there has been a sustained research activity about the contribution of tourism to employment, social development, and climate change (Leonard 2015; Kizielewicz 2020; Clemente et al. 2020). It is a sector that influences and is, in turn, influenced by a multitude of factors (Zopiatis et al. 2019), such as natural causes (Durocher 1994; Pottorff and Neal 1994; Pearlman and Melnik 2008; Rittichainuwat 2013), political issues (Ioannides and Apostolopoulos 1999; Mansfeld 1999), or the most predictable factor, economic issues (Henderson 1999a, 1999b; Prideaux 1999). Therefore, the interactions generated by tourism activity entail positive and negative impacts on local communities (Lin and Lu 2016). Positive effects are related to the opportunities for investment, profitability, and employment generation (Chen et al. 2021). Tourism favors the creation of new infrastructures and the value of the natural and historical resources (Wang and Pfister 2008; Andereck and Nyaupane 2011; Dyer et al. 2007; Gursoy et al. 2002). However, the crisis can hurt tourism, especially when this sector is the driving force behind the development of a territory (Ritchie and Jiang 2019; Jiang et al. 2019). In recent years, there has been renewed interest in the study of the impacts on the residents and their relations with the tourists. In fact, tourism activity can cause damage and negative attitudes to be perpetuated (Almeida-García et al. 2016). Frequently perceived impacts are related to overcrowding of infrastructure and public spaces (Lindberg and Johnson 1997; Sheldon and Abenoja 2001), drug and alcohol consumption (Diedrich and García-Buades 2009; Haralambopoulos and Pizam 1996), noise and insecurity, and an increase in prices (Liu and Var 1986).

The COVID-19 pandemic, as with other crises, can exacerbate inequalities (Jamal and Higham 2021). However, health crises, such as COVID-19, seem to be recurrent, generating uncertainty in financial markets and causing severe economic problems. Therefore, it is not only interesting to observe their impacts, but also possible solutions from different points of view. Examples are the 1918/1919, 1957/1958, and 1968/1969 cycles, in which epidemics caused higher mortality rates and negative consequences in relation to the economy.

The repercussions have been magnified, increasing the risks of disease spread, favored by conflicts, population movements, social interactions, and climate change (Hidalgo García 2019; Saunders-Hastings and Krewski 2016). Therefore, after the pandemic declaration, many countries opted to close their borders to curb the virus. However, the current global business model is contrary to the complete isolation of almost any territory. Tourism has been an engine of recovery in the past crisis of 2008, despite the fact it has suffered some uncertainties due to Brexit, other geopolitical issues, and social tensions. Therefore, recovery is a complex process. The first thing to do is to re-conceptualize the indicators and figures provided by the forecasts before the health crisis and think based on a world that is temporarily crumbling in many economic sectors, especially tourism (Torres and Fernández 2020). These have undermined their development, leading to economic losses and social problems (Clavellina Miller and Domínguez Rivas 2020).

As part of its global mission, the UNWTO was to review the growth model foreseen for 2020–2021, which placed an increase in activity between 3 and 4%. However, current data brings us closer to business recovery forecasts throughout 2022 and 2023. The first 2022 issue of the UNWTO World Tourism Barometer indicated that International tourism rebounded moderately during the second half of 2021, with international arrivals down 62% in both the third and fourth quarters compared to pre-pandemic levels. According to limited data, international arrivals in December were 65% below 2019 levels (UNWTO 2022).

In its most recent history, tourism has become one of the most relevant economic activities of the Spanish economy (Vallejo-Pousada 2013; Larrinaga and Vallejo Pousada 2013). The Andalusian tourism sector needs to reinvent itself to maintain its leadership as one of the most visited territories in Spain. However, although their long-term marketing strategy was focused on the search for a tourist with high purchasing power, tourism managers have opted for operational marketing strategies to return to the previous state.

After this introduction, this paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 introduces a complete review of the literature. Section 3 proposes the research model through a mixed methodology. Finally, Section 4 shows the results obtained, and Section 5 and Section 6 offer a discussion and conclusions, limitations, and potential topics for future research.

2. Literature Review

In contemporary times, the word crisis is also used to refer to a ‘profound and consequential change in a process or situation, or in the way, it is appreciated’ (RAE 2021). Economic history shows that crises are part of the normal operations of economies. They occur over time and constitute economic cycles, affecting both the developed world and the Third World (Schumpeter 2002; De Huerta Soto 2009).

Moreover, the reasons for a crisis are innumerable. For example, the relationship between tourism and terrorism has been studied in the academic literature. Not only because of the impact that a terrorist attack has on a tourist destination, but also because of the recovery process that it requires (Kepel 2002; Blake and Sinclair 2003; Essner 2003; Kuto and Groves 2004; Bhattarai et al. 2005; Hu and Goldblatt 2005; Yuan 2005; Young-Sook 2006; Araña and León 2008; Korstanje 2015; Aledo et al. 2020). In this relationship, media management plays a fundamental role since perceptions and attitudes can be easily manipulated in times of crisis (Korstanje and Clayton 2012). Insecurity, therefore, makes destinations vulnerable (Calgaro et al. 2014) because destinations are perceived as less attractive by potential tourists (Glaesser 2003).

In the case of COVID-19, the crisis has been global. The epidemic has been a tragedy for society, but it has also provided an opportunity for change in the world (Hall et al. 2020; Gills 2020). This perception is shared by Sneader and Singhal (2020) who assert that the pandemic has led to a restructuring of the world economic order. However, there is previous experience in health catastrophes, such as the case of Taiwan’s SARS (Yang and Chen 2009; Xu and Grunewald 2009, p. 104).

Tourism is a very complex sector that benefits from the movement of people, so any situation that impedes free movement poses a risk to the continuation of the activity. Indeed, the impacts on the tourism industry are difficult to solve (Laws and Prideaux 2006). Some authors affirm that to overcome it, a retrospective analysis should be carried out (Faulkner and Vikulov 2001). This is in addition to the importance of tourism in the economy of the territory. If tourism contributes a high percentage of the GDP, a paralysis of the sector would trigger an economic crisis. Hence, there is a need to have efficient tourist planning (Gurtner 2016).

Economic historians affirmed the existence of including tourism as an explanatory theory of the development of the Spanish economy in the 20th century (Vallejo-Pousada 2013). By the early 1930s, Spain had already become one of the thirteen major tourist countries in the world (Vallejo-Pousada 2019).

In 1936, France established the first ‘paid holidays’, and this favored the recovery of Europe after the Second World War. A little later, mass tourism was imposed in Spain. The tertiary sector, which includes tourism, helped to curb the crisis of the 1970s in Spain, consolidating itself in the following decades as a formula for growth and overcoming conflicts (Ybañez Bueno 1997).

Many decades have passed between the so-called Great Recession of 1929 and the economic crisis of 2008, decades that have been analyzed from various perspectives in a global work dedicated to explaining the Great Depression and the Great Recession of the first decade of the 20th century (Martin-Aceña 2012). The recent economic crisis that began in 2008 has also affected the Spanish tourism sector, especially the behavior of domestic tourism consumption (Cuadrado-Roura and López Morales 2015). However, attention was once again focused outside Spain’s borders. Attracting the attention of international tourists with high purchasing power was the solution to an economy based on tourism and construction. When foreign investment ceased and the mass tourist was only looking for low prices, the economy went into recession. One of the main drawbacks was the interruption in the flow of financing, but the liquidity injections managed to reverse negative trends. In the case of the autonomous community of Andalusia, the previous economic crisis showed that foreign tourism became the economic engine that improved the balance of payments (Dancausa Millán et al. 2021).

In any strategic situation, the capacity to handle a crisis and the measures applied for the economic recovery will be transcendental in the medium- and long-term projection of the crisis (Ritchie 2004, 2008). A study by Rittichainuwat (2006) referring to Thai tourism after the tsunami crisis in 2004 revealed that lowering prices for tourist packages was not a good long-term tool. In addition, the tourists returned to the destination after verifying that the necessary measures had been taken to restore security. Although crises seem to disappear and many destinations return to normality within one year (Alvarez de la Torre and Rodríguez-Toubes Muñiz 2013; Rodrigues and Mallou 2014), the repercussions in the economy could be suffered for years. It is, at this point, that the resident becomes most important. In the absence of external income, domestic consumption must become more valuable.

The pandemic has affected the way we live and relate to each other, partly because of the measures that governments had to put in place to stop the spread of the disease. Restrictions would have been unthinkable in any other context (Baum and Hai 2020). Along with this, social effects caused by distancing (Sikali 2020) and the use of masks (Aranaz Andrés et al. 2020) have become two common elements in everyday life. Therefore, for tourism, making successful decisions in change processes is very important because they can determine its future (Hanlan et al. 2006). For this reason, it is important to act quickly to foster a climate of confidence with the creation of new policies that allow the recovery of the destination (Persson-Fischer and Liu 2021; Karl 2018). The return to normality is particularly slow in this sector, and different solutions will have to be implemented in coordination with the agents involved. The step before planning should include close collaboration between all the actors in the territory.

Preparing an action plan will be fundamental (Waller et al. 2014; Gurtner 2016; Martens et al. 2016), and this should include the perceptions of institutions and citizens (Floyd et al. 2004). In this sense, residents appear as a key element both for the evaluation of impacts (Teixeira and Ribeiro 2020) and for the better management of the territories through their brand (Cruz-Ruiz et al. 2019). The literature is extensive in talking about possible crisis tools, but not in analyzing the residents’ perceptions of these possibilities and studying their feasibility. In addition, the tourism product needs local support not only for the growth of the destination, but also for its sustainable development (Allen et al. 1988; Williams and Lawson 2001; Byrd et al. 2009; Gursoy et al. 2010; Nunkoo and Gursoy 2012; Sharpley 2014). A crisis plunges the destinations into chaos, and this situation needs to be recovered (Prideaux et al. 2003). In this sense, the opinion of residents is important for the global reconstruction of the sector (Floyd et al. 2004). Communication among stakeholders, the media, events, and marketing messages were necessary elements for reconstruction (Hayden 2009; Walters and Mair 2013; Séraphin et al. 2019; Perkins et al. 2020; Ghannad et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2020). Attention must be paid to elements such as the lack of disaster management plans, damage to the image and reputation of the destination, and changes in tourist behavior after the crisis (Mair et al. 2016, p. 1). The marketing of a tourist destination depends fundamentally on the options for generating positive images (Salazar and Graburn 2014), and residents are projecting an image with their messages, behaviors, and opinions. Media coverage seems to be another crucial agent. As stated by Yu et al. (2020), media could dynamically change the perceptions of tourists. For them, the risk of travel must be taken into account, as it facilitates decision making and planning in a health crisis (Reisinger and Mavondo 2005). Communication channels will be vital in the return to normality (Hass 2009; Carlsen and Liburd 2008). However, the resident who became a tourist may not pay attention to all these aspects. In this sense, during the pandemic, institutions have not been working on attracting residents, but on how to attract tourism when COVID-19 disappears. Previous research showed the value of knowing the typology of tourists who are more resistant to insecurity and the factors involved in decision making (Hajibaba et al. 2015), especially in post-crisis scenarios (Muñiz and Fraiz Brea 2010; Rodríguez-Toubes Muñiz and Fraiz Brea 2012; Mair et al. 2016; Domdouzis et al. 2016).

Marketing strategies should be taken into account in the future reconstruction of tourist cities. These actions can be useful to restore lost identity and confidence in the territories (Avraham and Ketter 2017; Qureshi and Dada 2019; Avraham 2020). Lanquar and Hollier (2002) refer to the fact that that tourism marketing increasingly reflects the opinion of tourists and locals, although this perception is less studied in the literature (Lawton 2005; Stylidis et al. 2017; Zerva et al. 2019). The success of tourism policies largely depends on the participation of the local population (Gursoy et al. 2002; Besculides et al. 2002; Gursoy and Rutherford 2004; Ritchie and Inkari 2006; Zhang et al. 2006; Tovar and Lockwood 2008; Fredline et al. 2013; Vargas-Sánchez et al. 2014; Sharpley 2014).

New technologies should play a key role in the recovery of the tourism industry. Information and communication technologies (ICT) will play a crucial role in the fight against COVID-19 (Takenaka et al. 2020). Technological advances have reduced the dependence on physical connectivity, offering alternative methods and maintaining urban functionality in times of crisis (Sharifi et al. 2021).

On the other hand, these advances, most notably ICT, the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), deep learning, and cloud computing have become the most relevant issues for smart cities. Indeed, the pandemic has offered an unprecedented opportunity to test their effectiveness (Chen et al. 2021; Almeida et al. 2020).

Consequently, since the beginning of the pandemic, numerous companies have relied on smart solutions to contain the spread of the virus and improve their ability to respond. Analyzing the impact of new technologies on both business strategies and consumer behaviors will provide more efficient management of the recovery from the economic crisis (Grewal et al. 2020).

RQ 1.

How has the pandemic impacted residents in Andalusia?

RQ 2.

Why do consumers of tourism products reject some destinations?

RQ 3.

How can the tourism sector curb the current crisis from the residents’ perspective?

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area

The present research was conducted in Andalusia. It is one of the seventeen autonomous communities of Spain. It is located in the extreme southwest of the European Union (Figure 1). Surrounded by two seas and two continents, this distinctive geographical feature has marked its history and has given this territory an open and multicultural identity (Junta de Andalucía 2020).

Figure 1.

Map of Andalusia (Spain). Source: maphill. (CC BY-ND).

According to data from the Survey of Tourist Movements at the Andalusian Border, this territory received 12,079,017 international tourists in 2019, which was an increase of 3.4% compared to 2018 (INE 2020). Although the forecast indicated a positive trend in 2020, COVID-19 completely paralyzed the tourist activity. According to the Office of the National Statistics Institute (INE), Andalusia received 4.2 million international tourists in 2021, approximately one-third of pre-COVID-19 levels. The number of tourists received by Andalusia between October and December 2021 exceeded five million two hundred thousand, 229.5% more than in the same quarter of 2020. In 2021, tourists increased by 49.8%, exceeding twenty million, and 70.3% of tourists came from Spain. The average daily expenditure made by tourists in Andalusia was 67.08 euros, 9.9% higher than the previous year (Junta de Andalucía 2022). It represents a timid recovery compared to pre-pandemic data. Although a positive balance is expected for the summer of 2022, new variants of the coronavirus, Brexit, and the conflict between Ukraine and Russia have once again set off alarm bells, as international tourism is the basis of this region.

3.2. Sampling, Data Collection, and Analysis

The study applies a quantitative and qualitative approach to deal with the research questions. This research examines the coronavirus crisis from Andalusians’ perceptions and the future implications for the tourism sector in this region. For this study, we employed data collected from a survey. A pilot study (25 surveys) was carried out to ensure the applicability and relevance of this instrument. No substantial alteration was made. The questionnaire was translated into Spanish and English. This is because there are residents from different nationalities. As indicated by Etikan et al. (2016), the snowball sampling method (non-probability sampling) is particularly suitable when the population of interest is difficult to reach. In this regard, due to quarantines and lockdown, it was impossible to conduct face-to-face surveys. Therefore, social networks were used. The questionnaire was created through Lime Survey Software and the link was sent via WhatsApp. Thanks to the progress of technology, these tools open new ways to conduct studies for a fraction of the time and cost. The study proceeded in two stages: in the first step, the survey was distributed among the author’s contacts, and in the second step, these contacts sent the survey to others, and so on. One of the potential risks of this type of sampling is that respondents will send the link to others with similar characteristics. This is why the initial set of participants was 63 people and the link was also sent by mail to create another answer network. All respondents participating in this study have given their consent for being part of this research. IBM ISPSS and NVIVO software were used to analyze the data and to present the findings of the study.

The questionnaire was divided into five sections. The first was related to socio-demographic characteristics. The variables analyzed were gender, age, level of studies, and level of income. The second was related to the trips per year and whether the participant had postponed or canceled a trip due to COVID-19. Whether the destination was national or international, and if, from the participant’s perception, tourism could help the economy to curb the crisis were the last questions in this group. The third part of the questionnaire included questions related to future purchase intent, the destination of future trips, changes due to the coronavirus, and proposals about how to re-start after the pandemic. The last part of the study focuses on the answers to the open questions. An analysis, categorization, and synthesis were carried out to provide an orderly presentation of the results.

4. Results

A total of 658 respondents participated in this research. No missing data were obtained because subjects had to answer each question before proceeding to the next. Regarding the socio-demographic characteristics of participants, the distributions are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

The distribution between gender showed that there was a high percentage of women (61.4%) answering the questionnaire in comparison with men (38.6%) (Table 2). With regard to age, a high response (57.3%) was giving by people from 46 to 60 years old (28.9%), followed by the 36 to 45 group (28.4%). The majority of respondents were graduated. These data are representative of Andalusia as it is the only Spanish community in which each of its seven provinces has at least one university. Regarding the level of income, the sample was well distributed among the groups (17.6%: 0 to 12,000 €; 25.5%: 12,001 to 24,000 €; 28.9%: 24,000 to 40,000 €; 28%: more than 40,000 €).

Table 2.

Gender distribution.

Of the respondents, 64.59% had a job, although 41.79 belonged to companies that had carried out temporary employment regulation expenditures. In these circumstances, companies were exempted from paying worker wages. This legal figure is a labor flexibilization measure that allows companies to reduce or suspend employment contracts. Although the workers were not working, they received a subsidy from the State. It was relevant for the research to know how many trips the participant takes a year. The result has been compared with the level of income to examine if there was a relationship between the variables (Table 3). The Chi-Square Test is show in Table 4.

Table 3.

Trip per year and level of income crosstabulation.

Table 4.

Chi-Square Tests.

The p value (0.001) is less than 0.05 so there is no difference between the means, and one can conclude that a significant difference does exist. The lower the level of significance, the stronger the evidence that an event is not due to mere coincidence (randomness). As the number of trips per year increases, so does the level of income. One of the main questions in this study was related to the change or cancelation of travel plans due to COVID-19. In this sense, 344 people affirmed to have had to cancel a trip for touristic purposes due to the coronavirus (Table 5). Regarding the destination of the canceled trip, there were no significant differences between national and international.

Table 5.

Destination of canceled trips.

Epidemics, as we have analyzed in the literature review, could affect the purchase intent of tourism products and services. In this sense, participants were asked about their willingness to travel within Spain, long-distance travel, or Europe (international). There was an increase of 18.6% in the intention to travel within the country. The main findings came when cross-referencing data on income and willingness to travel. Subjects who claimed to have higher incomes (over 40,000) were the most likely to travel internationally (69%). However, participants who reported incomes up to 12,000 euros had the willingness to travel within Spain (94%). Overall, there is a greater willingness to travel within a Spanish territory (Table 6). It should be mentioned that only 15.2% have the willingness to travel within Andalusia.

Table 6.

Destination of future trips.

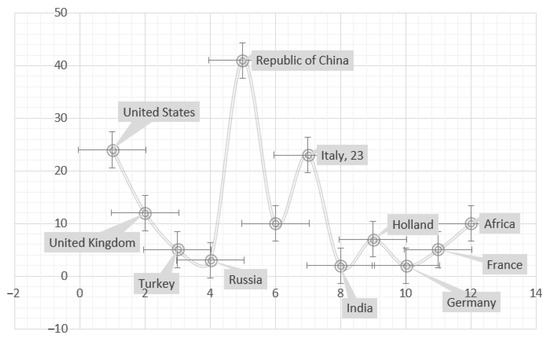

They were also asked about when they will start traveling and, in this sense, the participants indicated that they would travel within Spain when the vaccination process was more advanced (80%), followed by I will travel regardless of how the vaccination progresses (20%). No participants chose any of the following options: I do not plan to travel until we are back to normal, or I will travel depending on the conditions at the destination. The data suggest that after COVID-19, there will be many changes in the form that tourism products are purchased. In this regard, 24.88% of participants (144 respondents) stated that they had removed some countries from their destination lists due to the pandemic. Although 66% of the participants had already chosen a travel destination, they chose to change it for a safer place. In this sense, the countries where the participants would not be safe are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Destinations rejected by Andalusians. Source: Authors.

Specifically, the destinations listed in Figure 2 were rejected for different reasons. A content analysis was carried out through the repetition of words mentioned by the participants. Table 7 shows the data of the countries mentioned by at least 25% of the participants.

Table 7.

Main reasons for rejections.

Concerning whether tourism would help mitigate the effects of the economic crisis, 80.5% agreed. One of the participants concluded that “the reconstruction of the economy should not be built on a paralyzed sector” while another added, “the economy of a territory like Andalusia cannot be based on such vulnerable tourism. Tourism is too dependent, and the economy must have a balance”.

Given the importance of the previous answer, participants were given the opportunity to propose measures and other aspects or ideas that could be useful to recover the post-pandemic situation in Andalusia. It can be seen in Figure 3 that the three most prominent words highlighted were “COVID-19 Tax”, “transparency”, and “security”, followed by “help”, “inland tourism”, “new products and technologies”, “adaptation”, “European policies”, “special needs”, “flexibility”, and “all-inclusive changes”. Other words were parts of phrases repeated throughout the answers—“HORECA”, “VAT”, “International routes”, “marketing campaigns”, and “virtual experience”.

Figure 3.

Word cloud. Source: Authors.

In this regard, open questions were asked about specific measures that could be applied in order to assess their feasibility and potential usefulness. Throughout these questions, we show a description of the ideas or changes proposed. The answers were categorized as specified in Table 8. To facilitate and illustrate the comprehension of the results, the authors have summarized the opinion with higher frequency.

Table 8.

Thematic analysis of the proposals.

The proposals related to Europe were the most numerous; 78% of the participants used the term Europe in some of their proposals. The thematic analysis showed that the proposals were divided into health, business, social perceptions, and tourism. Social perceptions were also considered proposals because, although they were critical of the lack of support, they indicated a necessary action for recovery. The use of spaces and the creation of protocols were the two central themes mentioned in the local proposals. Residents think that increasing the use of public space will lead to increased sales. They also consider that if catering occupies more public space it will also help safety. All participants mentioned an economic proposal. Aid to the sector and the population are the most repeated proposals among the participants. It is necessary to indicate that residents should consider proposals for advertising purposes as a way to recover from this crisis. Regarding technological proposals, contactless services and virtual experiences were the most frequently mentioned among residents.

5. Discussion

This study has examined how the coronavirus pandemic has affected the Andalusia region and how, according to the residents’ perceptions, tourism could help stem the crisis. Regarding the limitations of this research, it could be argued that it was not possible to give the exact figure of how many of the respondents would continue to work or how many of them would lose their jobs. During the field activities, 54.54% (275) of workers were included in the temporary employment regulation. This figure suggests important impacts on the business fabric of Andalusia. Concerning the first research question, the economic capacity suffered a dramatic reduction due to the coronavirus. A total of 52.28% of respondents canceled their trips due to the coronavirus crisis and almost half (45%) of these trips had an international destination. The fact that the Spanish government launched the temporary employment regulation has led citizens to a situation of uncertainty.

In terms of income distribution, as income increases, the number of trips rises as well. It makes sense in terms of economic capacity as a person will be able to spend more money on a holiday if he/she has more financial capacity. Despite this, most of the participants with lower incomes stated that they would travel to a national destination. This protectionism is in agreement with Kuto and Groves (2004) when affirming that the sector should encourage local tourism. In the case presented by these authors, based on the terrorist attacks in Kenya, local tourism was a starting point that, together with a crisis agenda, led to a positive economic result for the hotels.

It should be stressed that this is a very important fact since it is clear that the residents of Andalusia were aware that the restoration of tourism had to start with their national territory. This contradicts some strategies such as that of Serbia where the provision of free vaccines helped increase the number of international tourists. Spain could not have carried out this type of strategy because it did not have surpluses, on the contrary, the population was stratified by groups to give priority to risk groups.

The findings indicated that a crisis with such implications affects the choice of destination. Concerning the second research question, destinations that are perceived as high-risk places are rejected. The research identified some different reasons for rejections. China topped the list, followed by Italy. The Andalusians were grateful for the help of China but considered that they would not travel to this country until the origin of the virus was clarified. In this regard, the media have played an essential role. Respondents said that at the beginning of the virus’ emergence, the media was focused on international news. This diverted our country’s concern. Non-transparency could be partly responsible for the dramatic situation in some European countries. This is also the reason for the rejection of African destinations. Residents think that Europe does not receive enough data about the figure in that continent.

Concerning European countries, the study revealed great findings. The factor that determined the rejection was not fear or insecurity. Previous studies have emphasized the importance of the fear factor in the destination choice. However, this analysis demonstrates another aspect. Participants stated that they were not receiving a solidarity response from the rest of the European Union countries, and therefore, if they did not show solidarity, the Andalusians would refuse to travel to these destinations. Some of the respondents affirmed that Europe must be a union of many cultures and they were concerned about the statements of the main political leaders of Germany and the Netherlands. The last question of the questionnaire was related to proposals to curb the future crisis. The results demonstrated two things. First, the Andalusians have a high degree of knowledge of their tourism industry, but at the same time, the proposals are grounded in recovering the same pre-Covid-19 tourist model. The main findings of this research were determined by the very detailed proposals on many different aspects. They are included within four broad categories: European, local, economic, and tourism proposals.

Concerning Europe, the proposals are related to the reasons for the rejection of some destinations. Residents consider that a united Europe is necessary and that an economic community is not enough. They propose that incentives be given to entrepreneurs, that the value of traditions is recognized and that a new tourism structure is created. Local government support emerges as another starting point to support the destination. Both residents of Andalusia and tourists take great advantage of the city’s life, which is why the occupation of public space takes on so much importance. Residents affirm that to create a sense of security it is necessary to allow restoration to expand the space. To this end, they believe that it is necessary to create new protocols in which all actors can contribute with their opinion. The Andalusians also say that it is not necessary to invest in infrastructure and that it is not necessary to make large economic outlays. Politicians must get involved and some have mentioned the famous case of Palomares. In January 1966, a bomber of the B-52G bomber of the United States Air Force collided with a tanker during mid-air refueling at 31,000 feet over the Mediterranean Sea. The Spanish Minister for Information and Tourism, Manuel Fraga Iribarne, and the United States Ambassador, Angier Biddle Duke, swam on beaches in front of the press to defuse the alarm of contamination that had been created in the media (Stiles 2006).

The economic proposals are based on aid for young people and vulnerable families as well as for tourists. The high price of tourist products is a drawback for residents to become tourists in their territory. The aim is for the residents to become the consumers of the tourist products of their territory.

In addition, they demand a reduction in VAT. Residents understand that tourism is a commodity that sustains the economy and, therefore, a VAT reduction is necessary. Regarding tourism proposals, residents believe that it is necessary to improve the image after the pandemic. In addition, they state that hotels should establish relationships with residents and not only with tourists. They affirm that it is necessary to put an end to the seasonality of the territory and for this, they base their proposals on marketing campaigns for foreign tourists, more transparency in the media, and the integration of new technologies. Concerning the latter, the elimination of contact and virtual experiences accounted for the majority of responses. In relation to marketing campaigns, Walters and Mair (2013) shown that it is necessary to run publicity campaigns for the most loyal tourists as they will be the first to return to the destination. In the case under study, the challenge has been that with the closing of borders, only locals could become consumers of the products and tourist attractions.

6. Conclusions

According to the results of this study, the inhabitants of Andalusia suffered significant impacts due to COVID-19. The most important one is shown in the number of workers who were subject to a labor force adjustment plan. When residents were asked whether tourism could help the economic recovery after the pandemic, they replied in the affirmative. However, they claim that the economy should not be based on a sector as vulnerable as tourism. Residents call for a change in the product fabric of Andalusia that might have been possible if most of the European aid had not been used to maintain the layoffs. Despite this, they understand the importance of domestic consumption, which has been shown when they proposed to change the destination of their international trips to destinations within the territory. The problem is that the opinions seem to be punctual since when the sector begins to recover, the international tourists are again the ones who collaborate in the balance of payments of Andalusia. Likewise, the rejection of some destinations is also striking. In particular, the Chinese territory could be understood as a natural rejection since it was the origin of the pandemic. However, rejections are increasing, and some of them are due to a lack of support or government statements against Spain. Therefore, the lack of external support becomes a relevant factor to take into account in future studies on the willingness to visit a tourist destination. The response to this pandemic cannot be only economic or financial because this global issue can become an opportunity to reinforce the structures of what Europe means.

The residents’ opinions have seemed to play a key role lately when we refer to the acceptance of the tourist or how both can coexist in the same territory. However, regarding how to stop the crisis, the findings reveal some contradictions. Residents bet on protectionist measures, but their main tourist destinations are international. They are aware that the exit from the crisis cannot lead to a price war with other tourist destinations, but at the same time, they affirm that if prices in Andalusia do not go down, they will continue to opt for trips to destinations where they get more services for the same money. It is cheaper for an Andalusian to travel to Punta Cana than to spend a week in Marbella or Santi Petri (Andalusia). It is necessary to point out that the locals have initiative, but they are aimed at an external client. Their proposals reflect that although they have realized that in a period of crisis, they are the ones who can contribute to recovering the economy, they end up returning to the previous state in which the target is the tourist with high purchasing power. In this sense, tourism management must pay attention to the residents because although the idea of lowering prices and maintaining them seems to be contradictory, it is possible for both to coexist. That is to say, the destination can maintain prices but, at the same time, it can launch offers to residents as the city’s museums do. In this way, the measure would be progressive. Some of the proposed measures start from a very protectionist point of view and this makes some of them go against the free competition. In this case, it would be necessary to adapt these types of measures with a great European agreement so that the single market is not damaged but benefits. This is another issue for future research to explore, and future investigations are necessary to validate these kinds of conclusions that can be drawn from this study.

The findings showed that local government initiatives may contribute to facing the challenges of Mediterranean cities. Andalusians identified that Europe should be a unit, and simultaneously, specific needs and solutions should integrate countries with similar characteristics, such as the Mediterranean countries. This is the key component in future attempts to overcome tourism recovery. The proposals aimed at what we could call regenerative tourism and tourism of proximity. The residents have perceived the need to develop a new tourism model that obtains profitability from safer environments, and a return to the origins where values and traditions allow sustainable development.

The results show that the resident is a source of proposals to be taken into account to overcome the crisis. However, it is also necessary to re-educate them. Andalusia is a destination that has undergone many changes throughout its history. Mass tourism has helped to recover an economy based on the tertiary sector in all previous crises, however, for some years now, and under the need to make the destination sustainable, the institutions created campaigns to transform the tourist product. Marketing strategies have been efficient, but neither residents nor tourism managers have taken advantage of the residents’ role. In fact, residents do not contemplate campaigns dedicated to encouraging tourism consumption among the local population. Five years ago, the Andalusian brand was characterized by the sun, the beach, the diet, and the climate almost exclusively. The opening of luxury hotels and museums is currently helping tourism with high purchasing power reach this territory. It has brought advantages and disadvantages. The residents used the term tourism-phobia, and now their concerns are the high prices. The residents complain about Europe, but while other destinations have used the funds for the restructuring of the productive sector, the Spanish Government has used them to maintain the same economic model. If Andalusians believe in the need to change the production fabric to make the economy less dependent, agents should work together. On the other hand, if the objective is to return to the same point before the crisis, the resident will not be able to bear the rise in prices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.R.-R.d.l.C. and L.C.-G.; methodology, E.C.-R., L.C.-G. and L.C.-G.; software, L.C.-G.; validation, E.R.-R.d.l.C., E.C.-R., and L.C.-G.; formal analysis, E.C.-R. and E.R.-R.d.l.C.; investigation, L.C.-G. and E.C.-R.; resources, E.C.-R.; data curation, E.R.-R.d.l.C. and L.C.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.R.-R.d.l.C. and L.C.-G.; writing—review and editing, E.C.-R. and E.R.-R.d.l.C.; visualization, L.C.-G. and E.R.-R.d.l.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all respondents for their kind cooperation for our questionnaires and the members of SEJ-121 and the University of Malaga (UMA) for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aledo, Antonio, Guadalupe Ortiz, Pablo Aznar-Crespo, José Javier Mañas, Iker Jimeno, and Emilio Climent-Gil. 2020. Vulnerabilidad Social y el Modelo Turístico-Residencial Español: Escenarios Frente a la Crisis de la COVID-19. Available online: http://www.albasud.org/noticia/es/1202/vulnerabilidad-social-y-el-modelo-tur-stico-residencial-espa-ol-escenarios-frente-a-la-crisis-de-la-covid-19 (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Allen, Laurence R., Patrick T. Long, Richard R. Perdue, and Scott Kieselbach. 1988. The impact of tourism development on residents’ perceptions of community life. Journal of Travel Research 27: 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Fernando, José Duarte Santos, and José Augusto Monteiro. 2020. The challenges and opportunities in the digitalization of companies in a post-COVID-19 World. IEEE Engineering Management Review 48: 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-García, Fernando, Mari Úngeles Peláez-Fernández, Antonia Balbuena-Vazquez, and Rafael Cortés-Macías. 2016. Residents’ perceptions of tourism development in Benalmádena (Spain). Tourism Management 54: 259–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alvarez de la Torre, Jaime, and Diego Rodríguez-Toubes Muñiz. 2013. Riesgo y percepción en el desarrollo de la imagen turística de Brasil ante los mega-eventos deportivos. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 11: 147–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, Kathleen L., and Gyan P. Nyaupane. 2011. Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. Journal of Travel Research 50: 248–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranaz Andrés, Jesús M., Maria Teresa V. de Castro, Jorge Vicente-Guijarro, Joaquin B. Peribáñez, Mercedes G. Haro, Jose L. Valencia-Martín, and Cornelia G. Montero. 2020. Mascarillas como equipo de protección individual durante la pandemia de COVID-19: Cómo, cuándo y cuáles deben utilizarse. Journal of Healthcare Quality Research 35: 245–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araña, Jorge E., and Carmelo J. León. 2008. The Impact of terrorism on tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research 35: 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, Eli, and Eran Ketter. 2017. Destination image repair while combatting crises: Tourism marketing in Africa. Tourism Geographies 19: 780–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, Eli. 2020. Combating tourism crisis following terror attacks: Image repair strategies for European destinations since 2014. Current Issues in Tourism 24: 1079–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, Tom, and Nguyen Thi Thanh Hai. 2020. Hospitality, tourism, human rights and the impact of COVID-19. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 32: 2397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besculides, Antonia, Martha E. Lee, and Peter J. McCormick. 2002. Resident’s perceptions of the cultural benefits of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 29: 303–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, Keshav, Dennis Conway, and Nanda Shrestha. 2005. Tourism, terrorism and Turmoil in Nepal. Annals of Tourism Research 32: 669–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, Adam, and M. Thea Sinclair. 2003. Tourism crisis management: US response to September 11. Annals of Tourism Research 30: 813–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, Erick T., Holly E. Bosley, and Meghan G. Dronberger. 2009. Comparisons of stakeholder perceptions of tourism impacts in rural eastern North Carolina. Tourism Management 30: 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calgaro, Emma, Kate Lloyd, and Dale Dominey-Howes. 2014. From vulnerability to transformation: A framework for assessing the vulnerability and resilience of tourism destinations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 22: 341–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, Jack C., and Janne J. Liburd. 2008. Developing a research agenda for tourism crisis management, market recovery and communications. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 23: 265–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Tzu-ling, Ching-cheng Shen, and Mark Gosling. 2021. To stay or not to stay? The causal effect of interns’ career intention on enhanced employability and retention in the hospitality and tourism industry. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education 28: 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavellina Miller, José Luis, and Mario Iván Domínguez Rivas. 2020. Implicaciones económicas de la pandemia por COVID-19 y opciones de política. Instituto Belisario Domínguez 81: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, Filomena, António Lopes, and Vitor Ambrósio. 2020. Tourists’ Perceptions on Climate Change in Lisbon Region. Atmosphere 11: 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cruz-Ruiz, Elena, Elena Ruiz-Romero de la Cruz, and Franciso J. Calderon Vázquez. 2019. Sustainable tourism and residents’ perception towards the brand: The case of Malaga (Spain). Sustainability 11: 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuadrado-Roura, Juan R., and Jose Maria López Morales. 2015. El Turismo, Motor del Crecimiento y de la Recuperación de la Economía Española. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10017/21517 (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Dancausa Millán, Mª Genoveva, Mª Genoveva Millán Vázquez de la Torre, and Ricardo Hernández Rojas. 2021. Analysis of the demand for gastronomic tourism in Andalusia (Spain). PLoS ONE 16: 0246377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Huerta Soto, Jesús. 2009. Dinero, Crédito Bancario y Ciclos Económicos. Los Angeles: Union Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Diedrich, Amy, and Esther García-Buades. 2009. Local perceptions of tourism as indicators of destination decline. Tourism Management 30: 512–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domdouzis, Konstantinos, Babak Akhgar, Simon Andrews, Helen Gibson, and Laurence Hirsch. 2016. A social media and crowdsourcing data mining system for crime prevention during and post-crisis situations. Journal of Systems and Information Technology 18: 364–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durocher, Joe. 1994. Recovery marketing: What to do after a natural disaster. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 35: 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, Pam, Dogan Gursoy, Bishnu Sharma, and Jennifer Carter. 2007. Structural Modeling of Resident Perceptions of Tourism and Associated Development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Tourism Management 28: 409–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essner, Jonathan. 2003. Terrorism’s impact on Tourism: What the industry may learn from Egypt’s struggle with al -Gama’a al -Islamiya. Security and Development IPS 688: 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, Ilker, Rukayya Alkassim, and Sulaiman Abubakar. 2016. Comparision of snowball sampling and sequential sampling technique. Biometrics and Biostatistics International Journal 3: 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faulkner, Bill, and Svetlana Vikulov. 2001. Katherine, washed out one day, back on track the next: A post-mortem of a tourism disaster. Tourism Management 22: 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, Myron F., Heather Gibson, Lory Pennington-Gray, and Brijesh Thapa. 2004. The effect of risk perceptions on intentions to travel in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 15: 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredline, Liz, Margaret Deery, and Leo Jago. 2013. A longitudinal study of the impacts of an annual event on local residents. Tourism Planning and Development 10: 416–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghannad, Pedram, Yong-Cheol Lee, Carol J. Friedland, Jin Ouk Choi, and Eunhwa Yang. 2020. Multiobjective Optimization of Postdisaster Reconstruction Processes for Ensuring Long-Term Socioeconomic Benefits. Journal of Management in Engineering 36: 04020038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gills, Barry. 2020. Deep restoration: From the great implosion to the great awakening. Globalizations 17: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glaesser, Dirk. 2003. Crisis Management in the Tourism Industry. Burlington: Butterworth-Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, Stefan, Daniel Scott, and C. Michael Hall. 2020. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 29: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, Dhruv, John Hulland, Praveen K. Kopalle, and Elena Karahanna. 2020. The future of technology and marketing: A multidisciplinary perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 48: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gursoy, Dogan, and Denney G. Rutherford. 2004. Host attitudes toward tourism: An improved structural model. Annals of Tourism Research 31: 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, Dogan, Christina G. Chi, and Pam Dyer. 2010. Locals’ attitudes toward mass and alternative tourism: The case of Sunshine Coast, Australia. Journal of Travel Research 49: 381–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, Dogan, Claudia Jurowski, and Muzaffer Uysal. 2002. Resident attitudes: A structural Modeling Approach. Annals of Tourism Research 29: 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtner, Yetta. 2016. Returning to paradise: Investigating issues of tourism crisis and disaster recovery on the island of Bali. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 28: 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibaba, Homa, Ulrike Gretzel, Friedrich Leisch, and Sara Dolnicar. 2015. Crisis-resistant tourists. Annals of Tourism Research 53: 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, C. Michael, Daniel Scott, and Stefan Gössling. 2020. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tourism Geographies 22: 577–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlan, Janet, Don Fuller, and Simon Wilde. 2006. Destination decision making: The need for a strategic planning and management approach. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development 3: 209–21. [Google Scholar]

- Haralambopoulos, Nicholas, and Abraham Pizam. 1996. Perceived impacts of tourism: The case of Samos. Annals of tourism Research 23: 503–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, Rabea. 2009. The Role of Media in Conflict and their Influence on Securitisation. The International Spectator 44: 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, Craig. 2009. Media Strategies for Marketing Places in Crisis: Improving the Image of Cities, Countries and Tourist Destinations—By Eli Avraham and Eran Ketter. Journal of Communication 59: E30–E33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, Joan C. 1999a. Asian tourism and the financial Indonesia and Thailand compared. Current Issues in Tourism 2: 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, Joan C. 1999b. Tourism management and the Southeast Asian economic and environmental crisis: A Singapore perspective. Managing Leisure 4: 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo García, María del Mar. 2019. Las enfermedades infecciosas: El gran desafío de seguridad en el siglo XXI. Cuadernos de Estrategia 203: 37–80. Available online: http://bibliodigitalibd.senado.gob.mx/handle/123456789/4829 (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Hu, Clark, and Joe J. Goldblatt. 2005. Tourism, terrorism, and the new World for Event Leaders. E-Review of Tourism Research 3: 139–44. [Google Scholar]

- INE. 2020. Retrieved July 29. Available online: https://www.ine.es/en/daco/daco42/frontur/frontur1219_en.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Ioannides, Dimitri, and Yiorgos Apostolopoulos. 1999. Political instability, war, and tourism in Cyprus: Effects, management, and prospects for recovery. Journal of Travel Research 38: 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, Tazim, and James Higham. 2021. Justice and ethics: Towards a new platform for tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 29: 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Yawei, Brent W. Ritchie, and Pierre Benckendorff. 2019. Bibliometric visualisation: An application in tourism crisis and disaster management research. Current Issues in Tourism 22: 1925–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Andalucía. 2020. Available online: https://www.juntadeAndalusia.es/Andalusia/economia/turismo.html (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Junta de Andalucía. 2022. Encuesta de Coyuntura Económica, 1 Trimestre. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/turismo/notaprensa.htm (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Karl, Marion. 2018. Risk and uncertainty in travel decision-making: Tourist and destination perspective. Journal of Travel Research 57: 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Gurneet. 2017. The importance of digital marketing in the tourism industry. International Journal of Research-Granthaalayah 5: 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepel, Gilles. 2002. Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Asif, Sughra Bibi, Ardito Lorenzo, Jiaying Lyu, and Zaheer U. Babar. 2020. Tourism and development in developing economies: A policy implication perspective. Sustainability 12: 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kizielewicz, Joanna. 2020. Measuring the Economic and Social Contribution of Cruise Tourism Development to Coastal Tourist Destinations. European Research Studies Journal XXIII: 147–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korstanje, Maximiliano Emanuel, and Anthony Clayton. 2012. Tourism and terrorism: Conflicts and commonalities. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 4: 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korstanje, Maximiliano Emanuel. 2015. The Spirit of Terrorism: Tourism, Unionization and Terrorism. Available online: http://riull.ull.es/xmlui/handle/915/16090 (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Kuto, Benjamin, and James Groves. 2004. The Effects of Terrorism: Evaluating Kenya´s tourism Crisis. E-Review of Tourism Research 2: 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar, Robert, and Robert Hollier. 2002. Le Marketing Touristique. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Larrinaga, Carlos, and Rafael Vallejo Pousada. 2013. El turismo en el desarrollo español contemporáneo. Transportes, Servicios y Telecomunicaciones 24: 12–27. [Google Scholar]

- Laws, Eric, Bill Faulkner, and Gianna Moscardo. 1998. Embracing and Managing Change in Tourism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Laws, Eric, and Bruce Prideaux. 2006. Crisis management: A suggested typology. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 19: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, Laura. J. 2005. Resident Perceptions of Tourist Attractions on the Gold Coast of Australia. Journal of Travel Research 44: 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leonard, Llewellyn. 2015. Mining and/or tourism development for job creation and sustainability in Dullstroom, Mpumalanga. Local Economy: The Journal of The Local Economy Policy Unit 31: 249–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Huei-Wen, and Huei-Fu Lu. 2016. Valuing residents’ perceptions of sport tourism development in Taiwan’s North Coast and Guanyinshan National Scenic Area. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 21: 398–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, Kreg, and Rebecca L. Johnson. 1997. Modeling resident attitudes toward tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 24: 402–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Juanita C., and Turgur Var. 1986. Resident attitudes toward tourism impacts in Hawaii. Annals of Tourism Research 13: 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Haiyan, Yung-ho Chiu, Xiaocong Tian, Juanjuan Zhang, and Quan Guo. 2020. Safety or Travel: Which Is More Important? The Impact of Disaster Events on Tourism. Sustainability 12: 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mair, Judith, Brent W. Ritchie, and Gabby Walters. 2016. Towards a Resarch Agenda for PostDisaster and Post-Crisis Recovery Strategies for Tourist Destinations: A Narrative Review. Current Issues in Tourism 19: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfeld, Yoel. 1999. Cycles of war, terror, and peace: Determinants and management of crisis and recovery of the Israeli tourism industry. Journal of Travel Research 38: 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, Hanno Michail, Kim Feldesz, and Patrick Merten. 2016. Crisis management in tourism—A literature based approach on the proactive prediction of a crisis and the implementation of prevention measures. Athens Journal of Tourism 3: 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Aceña, Pablo. 2012. Pasado y Presente: De la Gran Depresión del Siglo XX a la Gran Recesión del Siglo XXI. Bilbao: Fundacion BBVA/BBVA Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz, Diego Rodríguez-Toubes, and José Antonio Fraiz Brea. 2010. Gestión de crisis en el turismo: La cara emergente de la sostenibilidad. Revista Encontros Científicos-Tourism and Management Studies 6: 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nundy, Srijita, Aritra Ghosh, Abdelhakim Mesloub, Ghazy Abdullah Albaqawy, and Mohammed Mashary Alnaim. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on socio-economic, energy-environment and transport sector globally and sustainable development goal (SDG). Journal of Cleaner Production 312: 127705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, Robin, and Dogan Gursoy. 2012. Residents’ support for tourism: An identity perspective. Annals of Tourism Research 39: 243–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, David, and Olga Melnik. 2008. Hurricane Katrina’s effect on the perception of New Orleans leisure tourists. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 25: 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, Rachel, Catheryn Khoo-Lattimore, and Charles Arcodia. 2020. Understanding the contribution of stakeholder collaboration towards regional destination branding: A systematic narrative literature review. Journal of Hospitality Tourism Management 43: 250–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson-Fischer, Ulrika, and Shuangqi Liu. 2021. The impact of a global crisis on areas and topics of tourism research. Sustainability 13: 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottorff, Susan M., and David M. Neal. 1994. Marketing implications for post-disaster tourism destinations. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 3: 115–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, Bruce. 1999. Tourism perspectives of the Asian financial crisis: Lessons for the future. Current Issues in Tourism 2: 279–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, Bruce, Eric Laws, and Bill Faulkner. 2003. Events in Indonesia: Exploring the limits to formal tourism trends forecasting methods in complex crisis situations. Tourism Management 24: 475–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, Reyaz A., and Zubair A. Dada. 2019. Post Conflict Rebuilding: An Exploration of Destination Brand Recovery Strategies. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal 6: 126–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAE. 2021. Available online: https://dle.rae.es/crisis (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Reisinger, Yvette, and Felix Mavondo. 2005. Travel anxiety and intentions to travel internationally: Implications of travel risk perception. Journal of Travel Research 43: 212–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, Brent W. 2004. Chaos, Crisis and Disasters: A Strategic Approach to Crisis Management in the Tourism Industry. Tourism Management 25: 669–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, Brent W. 2008. Tourism disaster planning and management: From response and recovery to reduction and readiness. Current Issues in Tourism 11: 315–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, Brent W., and Mikko Inkari. 2006. Host community attitudes toward tourism and cultural tourism development: The case of the Lewes District, Southern England. International Journal of Tourism Research 8: 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, Brent W., and Yawei Jiang. 2019. A review of research on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management. Annals of Tourism Research 79: 102812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, Hannah, Edouard Mathieu, Lucas Rodés-Guirao, Cameron Appel, Charlie Giattino, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, and Max Roser. 2020. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Rittichainuwat, Bongkosh N. 2006. Tsunami recovery: A case study of Thailand’s tourism. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 47: 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittichainuwat, Bongkosh N. 2013. Percepciones de los turistas y proveedores de turismo hacia la gestión de crisis en caso de tsunami. Gestión del Turismo 34: 112–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Adriana Silva, and Jesús Varela Mallou. 2014. A influência da motivação na intenção de escolha de um destino turístico em tempo de crise económica. International Journal of Marketing, Communication and New Media 2: 5–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Toubes Muñiz, Diego, and José Antonio Fraiz Brea. 2012. Desarrollo de una política de gestión de crisis para desastres en el turismo. Tourism and Management Studies 8: 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, Noel B., and Nelson H. H. Graburn. 2014. Tourism Imaginaries: Anthropological Approaches. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders-Hastings, Patrick R., and Daniel Krewski. 2016. Reviewing the history of pandemic influenza: Understanding patterns of emergence and transmission. Pathogens 54: 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schumpeter, Joseph. A. 2002. Business Cycles: Theoretical, Historical, and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process. Zaragoza: Zaragoza’s University, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Séraphin, Hugues, Mustafeed Zaman, and Anestis Fotiadis. 2019. Challenging the Negative Image of Postcolonial, Post-conflict and Post-disaster Destinations Using Events. Caribbean Quarterly 65: 88–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, Ayyoob, Amir Reza Khavarian-Garmsir, and Rama Krishna Reddy Kummitha. 2021. Contributions of Smart City Solutions and Technologies to Resilience against the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Literature Review. Sustainability 13: 8018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, Richard. 2014. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tourism Management 42: 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, Pauline J., and Teresa Abenoja. 2001. Resident attitudes in a mature destination: The case of Waikiki. Tourism Management 22: 435–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikali, Kevin. 2020. The dangers of social distancing: How COVID-19 can reshape our social experience. Journal of Community Psychology 48: 2435–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sneader, Kevin, and Shubham Singhal. 2020. Beyond Coronavirus: The Path to the Next Normal. Brussels: McKinsey and Company, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Stiles, David. 2006. A Fusion Bomb over Andalusia: U.S. Information Policy and the 1966 Palomares Incident. Journal of Cold War Studies 8: 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, Dimitrios, Amir Shani, and Yaniv Belhassen. 2017. Testing an integrated destination image model across residents and tourists. Tourism Management 58: 184–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takenaka, Aiko Kikkawa, Raymond Gaspar, James Villafuerte, and Badri Narayanan. 2020. COVID-19 Impact on International Migration, Remittances, and Recipient Households in Developing Asia. Mandaluyong: Asian Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, Diego, and Cadima J. Ribeiro. 2020. Residents’ Perceptions of the Tourism Impacts on a Mature Destination: The Case of Madeira Island. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1822/63746 (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Torres, Raymond, and María Jesús Fernández. 2020. La política económica española y el COVID-19. Cuadernos de Información Económica 275: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar, Cesar, and Michael Lockwood. 2008. Social impacts of tourism: An Australian regional case study. International Journal of Tourism Research 10: 365–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. 2022. World Tourism Barometer, January 2022. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Vallejo-Pousada, Rafael. 2013. Turismo y desarrollo económico en España durante el franquismo, 1939–1975. Revista de la Historia de la Economía y de la Empresa 7: 423–52. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo-Pousada, Rafael. 2019. Turismo en España durante el primer tercio del siglo xx: La conformación de un sistema turístico. Ayer: Revista de Historia Contemporánea 114: 175–211. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Sánchez, Alfonso, Nuria Porras-Bueno, and Ángeles Plaza-Mejía. 2014. Residents’ attitude to tourism and seasonality. Journal of Travel Research 53: 581–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, Mary J., Zhike Lei, and Robert Pratten. 2014. Focusing on Teams in Crisis Management Education: An Integrated and Simulation-Based Approach. Academy of Management Learning and Education 13: 208–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, Gabrielle, and Judith Mair. 2013. The effectiveness of post-disaster recovery marketing messages: The case of the 2009 Australian bushfires. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 29: 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yasong, and Robert E. Pfister. 2008. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism and perceived personal benefits in a rural community. Journal of Travel Research 47: 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, John, and Rob Lawson. 2001. Community issues and resident opinions of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 28: 269–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Feng, Wenxia Niu, Shuaishuai Li, and Yuli Bai. 2020. The Mechanism of Word-of-Mouth for Tourist Destinations in Crisis. SAGE Open 10: 215824402091949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Jing, and Alexander Grunewald. 2009. What Have We Learned? A Critical Review of Tourism Disaster Management. Journal of China Tourism Research 5: 102–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Hao-Yen, and Ku-Hsieh Chen. 2009. A general equilibrium analysis of the economic impact of a tourism crisis: A case study of the SARS epidemic in Taiwan. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 1: 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybañez Bueno, Eloy. 1997. Respuestas españolas en las diversas fases del fenómeno turístico. Estudios Turísticos 133: 41–76. [Google Scholar]

- Young-Sook, Lee. 2006. The Korean War and tourism: Legacy of the war on the development of the tourism industry in South Korea. International Journal of Tourism Research 8: 157–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Meng, Zhiyong Li, Zhicheng Yu, Jiaxin He, and Jingyan Zhou. 2020. Communication related health crisis on social media: A case of COVID-19 outbreak. Current Issues in Tourism 24: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Michael. 2005. After September 11: Determining its Impacts on Rural Canadians travel to U.S. E-Review of Tourism Research 3: 103–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zerva, Konstantina, Saida Palou, Dani Blasco, and José Antonio Benito Donaire. 2019. Tourism-philia versus tourism-phobia: Residents and destination management organization’s publicly expressed tourism perceptions in Barcelona. Tourism Geographies 21: 306–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jiaying, Robert J. Inbakaran, and Mervyn S. Jackson. 2006. Understanding community attitudes towards tourism and hosteguest interaction in the urban-rural border region. Tourism Geographies 8: 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zopiatis, Anastasios, Christos S. Savva, Neophytos Lambertides, and Michael McAleer. 2019. Tourism stocks in times of crisis: An econometric investigation of unexpected nonmacroeconomic factors. Journal of Travel Research 58: 459–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).