Abstract

When missing reliable comparables, estimating inappropriately is a high risk in the use of both market-oriented and income approach methods. Therefore, it is useful to identify effective alternatives in accordance with the estimation method to arrive at the estimated value in the absence of comparables. This paper examines the use of the asking price for estimating the market value of a fruit tree orchard, missing comparable data of similar assets. The analysis was conducted by considering two different scenarios. In the first, asking prices from the same segment of the land to be estimated were used in two market-oriented appraisal methods: the General Appraisal System (GAS) and the Nearest Neighbors Appraisal Technique (NNAT). In both these approaches, market prices were replaced with detected asking prices. The second scenario was based on the use of the Remote Segments Approach (RSA). The comparison was conducted between the market segment of the fruit orchard to be valued and other comparison market segments, consisting of three other species of fruit trees, grown in the same area where the fruit orchard to be estimated is located. The results showed that in the first scenario, the estimated value appeared to be unreliable and excessively high compared to actual market conditions. Using the segment comparison method, which applies asking prices for the purpose of determining the capitalization rate, produced more reliable results. The appraisal also appeared more objective, transparent, and consistent with valuation standards. In the presence of similar limiting conditions, RSA can be an effective support to the activity of the appraiser in the valuation process of agricultural land.

Keywords:

asking price; market comparison; land market; evaluation standards; income capitalization; Remote Segments Approach; JEL Classification:

D40; E43; Q12; Q15; R39

1. Introduction

In the estimation of agricultural land, it is very common that there is no availability of comparison assets similar to the land to be estimated, and whose data can be used to construct the comparison function. This is a rather common condition in the agricultural land market, due to the low frequency with which sales occur and the dis-uniformity that generally characterizes agricultural land. In the case of missing comparison data, therefore, estimation by income capitalization should be used (IVS 2022; TEGoVA 2020; Italian Property Valuation Standard 2018). This involves determining the income to be attained from cultivation and the rate to be used to perform the capitalization. The income can be inferred by drawing up an economic balance sheet for estimation purposes. The capitalization rate, not being a quantity expressed by the market, is derived by inductive or deductive research (Simonotti 2019).

The difficulty of finding useful data may lead the appraiser to operate in an approximate manner by including invalid comparables in the comparison function. Under these circumstances, the risk of estimating inappropriately can affect the use of both market-oriented and income approach methods.

In the income approach, if the appraiser uses a capitalization rate obtained inappropriately, it could be because it is derived from subjective and opaque valuations. In the use of market-oriented methods, in the absence of comparison prices, on the other hand, the reliability of the estimate may be impaired by the use of asking prices instead of actual market prices. Since the objective of an appraisal is to provide an objective identification of the market value of a property, providing an inappropriate result leads to inevitable negative economic and social consequences, as well as for the parties involved (Italian Property Valuation Standard 2018).

In this regard, it may be useful to identify effective alternatives for arriving at the appraisal value in the absence of comparables, which conform to the estimative method and are capable of constituting a valid support to the appraiser operating under severely limiting conditions for the development of a comparison function.

In this paper, we propose the possibility of employing the asking price for estimating the market value of a fruit tree orchard with missing comparison data (prices and incomes) of similar assets, which may constitute one of the extreme situations in which to determine the appraisal value.

This is used, in particular, to develop a comparison function between different segments to derive a capitalization rate for applying the income approach to reach the market value of a fruit orchard. Via the proposed approach, the analysis shows that with missing comparison data in the same segment, it is possible to obtain a more reliable estimated value containing the distorting effects on the estimated value. The result of the application is then compared with those obtained by using the asking price with two different market-oriented procedures.

The application is carried out by making a comparison between the segment to which the asset to be estimated belongs and other comparable segments. In this regard, for the estimation of the market value of a fruit orchard for which there are no comparison prices and incomes, the use of the Remote Segments Approach (RSA; Simonotti 2019) is proposed. The comparison function is carried out between the segment in which the fruit orchard to be estimated is located and other segments consisting of other fruit tree crops located in the same area where the subject is cultivated. In each of these segments, the intensities of the relevant characteristics on the market value are measured.

The methodology used, while allowing for a second-best result because it is not derived from actual exchange prices, is otherwise in accordance with the estimation method. Moreover, since from what has been possible to verify there is a lack of a similar application referring to the estimation of agricultural land, it is believed that the approach adopted here may be adaptable to analogous estimation contexts. The methodology followed here also appears to comply with the requirements of clarity and verifiability stated by valuation standards (Italian Property Valuation Standard 2018). It also appears to be quite interesting because the topic of asking price in property appraisals continues to be a relevant topic in the appraisal discipline (Knight 2002; Anglin et al. 2003; Węgrzyn and Kuta 2024). To the best of our knowledge, the case study examined here represents one of the first applications of asking prices in the estimation of agricultural land.

The paper is structured as follows. After some background on asking price and a description of the RSA, the application for estimating a fruit orchard in an intermediate year of the growing cycle is illustrated, in the absence of comparison data belonging to the same market segment. The result is compared with those obtainable by a market comparison using the detected asking price. In the concluding remarks, some possible insights are suggested, toward which further research and verification can be directed.

2. Some Implications of Asking Price on Market Value

In addition to the real estate data (prices, incomes, and technical-economic characteristics), the results obtained from the market survey to identify the assets to be compared may also consist of other elements (extra data), useful to configure the asset to be estimated and the segment to which it belongs. These include the price requests made by sellers—the asking price—market quotations, and real estate information, which comprise all the news and indications valid for practical and immediate use in estimation (trends, economic indices, etc.) (Simonotti 2019).

Regarding the use of the asking price, valuation standards point out that they are indicative of market trends and cannot be understood as prices in the proper sense or as substitutes for market prices (Italian Property Valuation Standard 2018). This is because they can also be subject to significant reductions during negotiations between buyers and sellers prior to purchase (Hacıevliyagil et al. 2022; Haurin et al. 2010).

It should also be noted that the asking price and real estate quotations represent price expectations and, therefore, cannot be considered valid for determining the market value of a property, which, according to Reg. (EU) 575/2013, is instead derived from the price actually paid (Italian Property Valuation Standard 2018).

The wide accessibility of the asking price and other real estate information of various kinds, facilitated by the development of digital technologies, however, increases the conviction that there is a vast possibility of their use in property valuation (Zhang et al. 2012), even in the appraisal of agricultural land.

The use of such data, however, is likely to be implemented in an inappropriate and artificial manner, probably in order to proceed more quickly with the appraisal. Their use, in fact, may avoid conducting much more accurate and time-consuming market analyses. For example, an in-depth analysis of comparables similar to the asset being valued or the preparation of the relative expected cash flow to be capitalized using the most appropriate procedure, as well as the collection of data useful for determining the most appropriate capitalization rate (Simonotti 2011).

The use of the asking price to estimate the market value, in addition to altering the reliability of the result of the appraisal, is not consistent with the appraisal methodology and best practices indicated by valuation standards (IVS 2022; TEGoVA 2020).

This is certainly an issue on which it might be appropriate to develop some deeper insights, taking into account that in many countries, such as Italy, the acquisition of real estate data is now facilitated by the possibility of consulting official documents of sale through the online availability of real estate transactions (Giuffrida et al. 2024). On the other hand, the possibility of having the asking price of real estate probably deserves more interest—especially in the Italian land market—in terms of analysis and insights, also for estimation purposes (Casini et al. 2023; Albrecht et al. 2016).

In active real estate markets, for example, characterized by frequent transactions, the use of the asking price (or extra data) could be considered admissible for the construction of the comparison function, if they are able to represent the real dynamics of the reference market and can be considered valid substitutes for prices (Han and Strange 2016; Khezr and Menezes 2016). In other contexts, however, the use of the asking price cannot be considered viable, as they cannot always be considered a substitute for real exchange prices (Liu 2021). Some urges toward their use tend, however, to be seen in the agricultural context as well, even in the presence of a land market that generally appears to be less dynamic than that of urban real estate (Hidayat et al. 2018). In the case of land markets, in fact, the availability of certain and reliable real estate data may fail to materialize in a way that is functional to the appraisal objectives. In these circumstances, it is more frequent to resort to solutions more in keeping with the appraiser’s expertise than with the canons of verifiability and replicability of estimative comparison, also recalled by valuation standards.

In this regard, it may be useful to ascertain whether effective alternatives can be identified to achieve the appraisal value of agricultural land in the absence of comparables.

This is, moreover, a rather frequent condition in the farmland market, given the low frequency with which agricultural land is sold, the orographic and agronomic unevenness that generally differentiates them even in local contexts, and the consequent difficulties of being able to acquire data of sold farmland, similar to that being estimated.

However, if the asking price and/or real estate quotations are available, it is not uncommon for appraisers to operate differently. Simulating that the asking price represents the real selling price (real exchange price), they carry out the estimation of the property using market-oriented procedures. Since the deviation between the asking price and real exchange price is often not predictable (Gohl et al. 2024; Glaeser and Nathanson 2017; d’Amato et al. 2023; d’Amato and Cucuzza 2022) and does not respond to a defined relationship, the estimation result could prove to be random and inaccurate (Manganelli et al. 2022). Not surprisingly, in this regard, standards require that the appraisal value be obtained through comparison with real exchange prices of similar assets (IVS 2022; TEGoVA 2020; Italian Property Valuation Standard 2018).

In this paper, a different use of the asking price is proposed. In particular, the possibility of employing the asking price in the comparison between the segment of the fruit orchard to be valuated and other comparable segments is analyzed. The aim is to derive the rate to be used in the capitalization of the income expected from the cultivation of the land to be valued. Extra data, such as the asking price, asking rent, property quotations, and other market information, however, constitute a useful set of knowledge for improving the appraisal valuation (Glower et al. 1998; Italian Property Valuation Standard 2018).

3. The Remote Segments Approach (RSA)

To estimate the market value of an asset in the absence of comparative data, the RSA can be used (Simonotti 2019). This approach involves a comparison between the market segment of the asset being estimated and one or more similar market segments being compared. The aim is to estimate the Gross Rent Multiplier (GRM) in the segment to which the asset to be valued belongs. The RSA, by some adjustments on the prices and incomes detected in the comparable segments, derives the rate to be used to develop the appraisal of the asset via an income approach.

The capitalization rate is determined using the inductive method by comparing with market segments for which prices and incomes are available (Simonotti 2019). According to the logic of remote search, the capitalization essay is expressed as a quantity derived from the ratio between the income and the price found in the respective market segments being compared (Simonotti 2006).

The RSA can be used with both data and extra data (e.g., asking price) surveyed in market segments close to that of the property being valued. In the absence of prices or income, the principle of comparison admits, in fact, that the survey takes place in market segments other than that of the property to be estimated (Italian Property Valuation Standard 2018; Simonotti 2019). When prices and incomes are measured in different market segments, they are subject to systematic adjustments according to the marginal values of the characters for which they differ. These adjustments can be expressed in percentage and value terms (Simonotti 2019).

Therefore, when prices and incomes are not available, the price/income ratio can be estimated, comparing the similar market segments with the reference market segment. Price and income can refer to the same property or to different properties but are included within the same market segment. They can also be made up of point data referring to individual properties or of average data calculated from sample data per market segment or of standardized average unit data (e.g., EUR/m2; EUR/m2 per year) (Simonotti 2019).

In general terms, given two properties (A and B) for which the corresponding prices and incomes (PA and RA, and PB and RB) are detected, the price/income ratio of the market segment (ρseg) is derived as the expected value by which the respective incomes occur:

where, and , Pseg and Rseg represent the average values.

If prices and incomes refer to different properties belonging to the same market segment, the relationship sought can be derived from average unit prices and incomes, even with different data. In this circumstance, Equation (1) assumes the following formulation:

where:

PC and PD represent property prices C and D, respectively.

RX, RY, and RW represent, respectively, the incomes of properties X, Y, and W.

SC and SD represent, respectively, the measurement of surfaces in buildings C and D.

SX, SY, and SW represent, respectively, the measurement of surfaces in buildings X, Y, and W.

As the sample size increases, the price/income ratio can be inferred from the respective average values:

When price and income data are not available in the segment in which the asset being valued falls, the price/income ratio is estimated using the RSA.

The use of the RSA requires that: (i) comparisons are made between the characters of the market comparable segments and the segment of the asset to be estimated, (ii) systematic adjustments are made to the prices or incomes found in one or more comparison market segments, (iii) the adjustments made, represented by the marginal prices or incomes of the segment characters, are expressed in percentage and value terms, and (iv) the determination of the value of the asset being valued is performed by using income capitalization.

Therefore, the capitalization rate is obtained inductively through the survey of incomes and market prices in different market segments from that of the property to be valued, and it is represented by the expected value of the capitalization rate, estimated through the comparison of market segments. The main steps of the RSA are the collection of data in segments and the search for marginal values of prices and incomes.

In particular, for its application, it is necessary to identify the market segment of the asset to be valued and the comparison segments, the detection of technical and economic characteristics, the detection of prices and incomes in the segments of comparison on a random sample of goods, and the detection of extra data and information in the segment of the property being estimated and in the comparison segments.

Once these steps have been completed, the characteristics of the segments are selected, and the corresponding marginal prices and incomes are analyzed. The application concludes with the determination of the price/income ratio from which the capitalization rate is derived.

The choice of comparison characters concerns those considered relevant by the appraisal and for which there are differences between the segment of the subject and the segments of comparison. Consistent with the principle of comparison, characters with the same intensity are not relevant for the purpose of the estimated comparison and are, therefore, not taken into account. In addition, each character shall be appropriately identified by means of an appropriate nomenclature and its technical and economic measure.

The analysis of marginal prices and revenues is aimed at making the estimation of adjustments in market segments. It is expressed by changes in their sign, not in absolute terms but in relative terms (percentage and value changes). The purpose of this stage is to be able to establish, on a par with the other characteristics, to what extent the market price level of the comparable segment differs from the price level of the segment in which the asset to be estimated belongs.

The result achieved is represented by the value that the prices and income of real estate falling in a comparable segment would have if they belonged to the segment in which the asset is estimated (Simonotti 2019).

Considering two segments, (H) and (K), the RSA provides that the marginal price, , of the generic character j, expressed in percentage, and the marginal income, , of the general character j, also expressed in percentage, can be derived, respectively, from the following equations:

With reference to different characteristics (e.g., location, destination, real estate typology, dimension, etc.), the adjusted price and income for all characteristics of the segment of the asset under assessment can, therefore, be determined by the following equations, which identify the prices [PK (H)] and revenues [RB (H)] that the asset belonging to comparable segment (H) would have if they fell into segment (K), in which the asset being estimated Equations (6) and (7) belongs:

The price/income ratio, ρK (H), of the segment of the asset to be valued is then equal to:

where PK (H) and RK (H) are the adjusted average unit prices and rent.

With reference to a number j of characters for two or more comparable segments (e.g., A and C and up to the generic segment Xi-th), the Equation (6) can be rewritten as follows:

and the Equation (6) can again be rewritten as follows:

where the symbols used assume the meanings corresponding to those indicated in the previous Equations (4) and (5).

…

…

Considering two comparison segments, A and C, the assessment ratio is identified through the expected value by the following equation:

The more similar the comparable segments are, and, therefore, the smaller the differences in characters, the less uncertain and more accurate the estimate; also, the greater the number of comparable segments, the less uncertain and more accurate the estimate will be. It is, therefore, essential for the appraiser to have an adequate knowledge not only of the technical and economic characteristics of the asset being valued and the market segment to which it belongs, but also the market segments of comparison (Simonotti 2019).

4. Materials and Methods

For the appraisal of market value of a specialized fruit orchard, the market survey showed that there were not any available prices and incomes from similar cultivations located in the same growing area, only asking prices and market quotations.

The market analysis made it possible to identify similar market segments from an economic and estimative point of view and to acquire the data useful for the purposes of the estimate (characters and their intensity; Table 1).

Table 1.

Relevant characteristics on the value of fruit orchards in the area.

In the comparison set, the segments that recorded differences in the relevant characteristics were taken into consideration as comparable. Precisely, for the location, it was measured in kilometers of distance from the nearest wholesale agri-food market, distinguishing those at a distance of ≤5 km from those located at a greater distance; for the surface area (measured in hectares), we distinguished those with a surface area of ≤5 ha from those with a larger surface area; for the bioeconomic cycle phase (measured in years since planting), we identified the production phase in which the orchard was located (planting, juvenile, maturity, senescence); for the cultivation regime, we distinguished whether the cultivation was carried out using conventional or organic techniques.

Missing comparable data for fruit orchards similar to the one being estimated, asking price, asking rent, and other market information were acquired in the segment to which the fruit orchard to be estimated belonged.

For the preliminary determination of the value of the agricultural land through the asking prices, two different market-oriented methods were used: the General Appraisal System (GAS) (Simonotti 1985) and the Nearest Neighbors Appraisal Technique (NNAT) (Isakson 1986).

The GAS is a multi-parametric and multi-equational method (Simonotti 1985; Simonotti 1987; Simonotti 1989) that estimates the value of the asset by solving a non-homogeneous system of linear equations through matrix calculation. The procedure can be formalized in symbols, as follows:

where:

is the vector of incognit terms, in which the first element represents the value of the asset being estimated and the subsequent elements indicate the marginal value of the individual relevant characteristics.

is the inverse matrix of the matrix of differences of the coefficients of the relevant characteristics, which exists when the matrix of coefficients is non-singular.

is the vector of known terms, represented by the prices of the comparable goods being compared (Simonotti 1985).

The set of comparison goods was made up of m goods, with n characteristics in common with the good being estimated. The data matrix of order (m + 1) × n, such that each generic element is aji with j = 0, 1, 2, 3, …, m and i = 0, 1, 2, 3, …, n, was constructed by arranging the coefficients of the relevant characteristics of the good to be estimated in the row with index 0, and those of the comparison goods, taken neatly one by one, in the following m rows, for each of the n characteristics in common. The vector of known terms was such that each generic element pj, with j = 1, 2, 3, …, m, indicated the price of the corresponding good m of the comparison set (Simonotti 1985).

The system of linear equations subjected to solution was constructed through non-redundant comparisons between the good being estimated with index 0 and each of the m comparable goods, and was made up of m linear equations in (n + 1) unknowns, such that when it admits the solution, it is the estimative solution (Simonotti 1985).

The estimative comparison for finding the value of the asset is represented by the system of linear equations, which, according to the relevance principle, consists of m useful, non-redundant comparisons, taking the following configuration (Simonotti 1985):

where S is the subject’s value (Simonotti 1985).

In this paper, the use of this method is proposed, admitting that it is possible to use the asking prices detected on the market in place of the market price vector. In the comparison function, the intensities measured in the n characteristics in common with the m comparable ones detected in the segment to which the asset being estimated belongs were considered as relevant characteristics. In the vector , the asking prices of the comparables were considered as known terms. Comparables were detected so that m equals n + 1 characteristics. Once the non-singular coefficient matrix was defined and the inverse matrix of the differences in the coefficients of the relevant characteristics () was calculated, the solution vector () was made up of n + 1 elements. The first element of this vector represents the value of the asset being sought, and the subsequent elements indicate the marginal value of the relevant characteristics in the market segment to which the asset being estimated belongs.

Another market-oriented method that was applied to determine the value of the fruit orchard using asking prices was the NNAT (Isakson 1986).

The NNAT applies a statistical calculation logic based on the measurement of the similarity between the asset being estimated and each comparison asset, arriving at the determination of the value of the asset through the product between a weighting factor and the prices of similar assets recorded on the exchange market. The weighting factor is made up of the relative ratio between the reciprocal of the similarity distance measure, neatly considered between the good being estimated and each comparison good, and the sum of the reciprocals of the similarity distances.

The use of similarity distances in the appraisal context allows to determine a measure of the level of similarity of the comparison goods with respect to the good being valued based on the relevant characteristics. It, therefore, allows to order the comparison goods with respect to their different level of similarity with the good to be estimated.

The NNAT can be depicted as follows (Isakson 1986):

where:

J = 1, 2, …, k, are the comparison goods,

Pj are the prices of the comparison goods,

W0J = is the weighting factor,

d0J = is the similarity distance between the good to be estimated and the comparison j good,

The similarity distance can be calculated in different ways. Commonly, having to express the level of similarity of goods with respect to variable characteristics, the standardized Euclidean distance is used in estimation fields (Equation (19))1:

In the case study presented, the determination of the value using the NNAT occurred by determining the weighting factor, W0J, based on the differences in the intensity of the characteristics between the comparison goods detected and the good being estimated. represents the value of the asking price detected (Table 2).

Table 2.

Asking price and quotations of avocado fruit orchards (* quotations).

To apply the RSA in the absence of prices and rental fees for other avocado fruit orchards, the market analysis was extended into comparison segments close to that of the land to be estimated. In these comparable market segments, made up of other fruit orchards, prices, rental fees, asking prices, and asking rents were detected.

The market segments for which it was possible to acquire data and information useful for applying the RSA were the following: citrus, drupaceous, and pomegranate fruit orchards. All of these cultivations, moreover, represent concrete alternatives for the intended use of agricultural land in the area in which the fruit orchard to be estimated is located and are, therefore, valid and representative elements for estimative comparison. Each tree cultivation, distinguishing itself by training method, planting layout, cultivation techniques used, irrigation needs, etc., constitutes, in fact, a different market segment and is perceived as such by local market operators.

Of the various relevant characteristics previously identified (Table 1), in the segments considered, those for which differences were detected were taken into consideration. In fact, from the price and income values obtained with the RSA (Equation (15)), the GRM and the average capitalization rate were obtained to apply the income approach.

To this aim, the cash flow from the fruit orchard to be evaluated was calculated, and the Net Present Value (NPV) and the value of the fruit orchard at the time of the estimate (n = 9) were estimated.

In this regard, technical and economic data were collected through direct interviews with farmers and were categorized into three different groups: structural data (e.g., farm size and farm investments), data on the production process (e.g., farming operations, inputs required for crop growing, and human labor), and farmers’ revenues (e.g., yield)2. Annual profits and costs incurred were calculated under the assumption that financial conditions remained constant over the entire period (Testa et al. 2018).

The NPV of the crop cycle represents the value of the fruit orchard when n = 0 and was calculated by the following equation:

where Bfn represents the annual income at the n-th year (revenues minus costs), n stands for the economic life of the orchard, q equals (1 + i), and i denotes the discount rate, assuming that financial conditions remained constant throughout the entire n bioeconomic period (Testa et al. 2018).

To calculate the value when the fruit orchard was aged 9 years, we adopted the “metodo dei redditi futuri”, assuming that the fruit orchard will be infinitely replanted at the end of each 30-year period of cycle duration (Tempesta 2018; Michieli and Cipollotti 2018; Simonotti 2003):

where Vm is the value to be estimated at the year m = 9, V0 is the value of the land without the trees, q equals (1 + i), and Bft represents the income at the year t, with t ranging from year m = 9 to year n = 30.

5. The Case Study: The Appraisal of an Avocado Cultivation

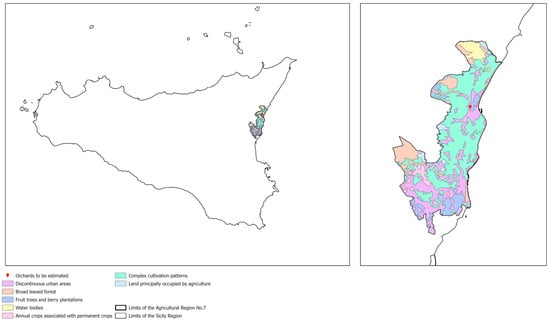

The fruit orchard to be estimated consisted of a specialized plant of avocado (cv. Hass), extended 1.2 hectares, with the same age (12 years). The density was 208 plants/ha (6 m by 8 m). It was cultivated with organic farming techniques and is located in Sicily, in the territory of “Piana di Mascali”, an alluvial plain located in the eastern part of the island, between the Ionian coast and the slopes of Volcano Etna. The area in which the fruit orchard is located is included within the agricultural region n. 7, called “Hills of Acireale”, at a distance of approximately 5 km from the local wholesale market for agricultural products. In the past, citrus groves (mainly lemon trees) were largely predominant in this area compared to other fruit crops (drupaceous, such as peach and cherry). In the following years, the unfavorable market dynamics of lemon production together have led to an increase in other fruit orchards. More recently, growing areas of avocado and pomegranate are increasing. Figure 1 shows the area of cultivation and the complex of crops, derived using Corine Land Cover (CLC 2018)

Figure 1.

Identification of the territorial area “Piana di Mascali”.

The cultivation of avocado in this area shows, therefore, a certain interest as a possible alternative to the traditional cultivation of lemons. Unfortunately, the size of the avocado crop to be estimated was rather small. However, it can be considered that it can still be an interesting case study to understand also from the perspective of the possibility of using the asking price in the appraisal of fruit orchards. In the area in which the cultivation of avocado to be estimated was located, nevertheless, the presence of small agricultural farms is not uncommon, as well as in other areas of the region (Crea 2024).

5.1. The Appraisal by Asking Price Using the Market-Oriented Approach

In the segment of avocado cultivation to be estimated, in the absence of price and income data of similar fruit orchards, asking price, asking rents, and other market information (land quotations) were acquired (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 3.

Asking rent of avocado fruit orchards.

All these “data” were acquired and verified through direct contacts in the local area with reliable interlocutors. These operators are active in the area of cultivation, mainly made up of owners and farmers, professionals in the sector, traders of agricultural products, brokers, and agents.

Regarding the appraisal of avocado cultivation using the asking prices detected in the same market segment, the use of two market-oriented procedures was proposed. Through the use of GAS, the estimated value was equal to EUR 61,740.18. Following the solution procedure, the estimated value obtained with the system of equations was obtained by comparing the values of the four relevant characteristics (localization, surface area, bioeconomic cycle stage, and farming regime) measured in the five available comparison assets (Table 2, comparable n. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6) consisting of other avocado fruit orchards and the corresponding asking prices detected. Table 4 shows the coefficient matrix, price vector, and appraisal vector.

Table 4.

Coefficient matrix, price vector, and appraisal vector of SGS.

The appraisal results with the NNAT are listed in Table 5, which reports the similarity Euclidean distance calculated between the avocado fruit orchard to be estimated and the other similar avocado fruit orchards, as well as the estimates of weights. The market value of the subject using the NNAT was EUR 84,336.44.

Table 5.

Determination of market value using the NNAT.

The difference in GAS and NNAT estimates depends on the different hypotheses assumed by each method. In theory, the NNAT value, due to the weighted assessment performed across the comparables, could be more reliable than the GAS solution. The inclusion of a weight inversely proportional to the similarity distance produces a more conservative estimate. In general terms, the results of the two procedures differed considerably, and both values appeared overestimated.

What must be noted, however, is that these results were conditioned by the use of asking price and not prices really paid. Looking at the farmland market, it should also be noted that the asking prices used may not represent valid elements to be used in the comparison function, both because the two estimated values appeared significantly divergent, and because both results appeared generally high compared to market values. This consideration was derived from the analysis conducted with privileged interlocutors and from some comparisons with the quotations of land in the area (Exeo 2023). We, therefore, propose a verification using a different approach.

5.2. The Appraisal by the Remote Segments Approach

The application of the MCS was conducted through the development of two phases. Initially, for each of the comparison segments considered (citrus, stone fruit, and pomegranate), the corresponding GRM was determined from the purchase and prices and rental fees, and from its inverse, the capitalization rate.

After this, following the comparison options valid for each characteristic between the segment to which the asset to be estimated belongs (avocado) and the comparable segments, the adaptations to be used to determine the correct average price and the correct average rent fee of the comparable segments were measured.

Although the reliability of the estimate increased as the number of segments used to make comparisons between the characteristics increased, the availability of only three comparison segments is compatible with the applicability of the approach. It is also representative of the cultivation area considered, whereby the cultivations considered were more widespread.

Prices and incomes detected were used, as it was possible to verify the presence of conditions of homogeneity with respect to the characters selected in each of the segments considered. Furthermore, each of these was located in the same area where the fruit orchard to be estimated was located (Table 6).

Table 6.

Prices and rental fees detected in the comparison segments.

For each comparable segment, the corresponding GRM and its inverse, the capitalization rate, were then determined (Table 7).

Table 7.

Capitalization rate in the comparable segments.

Furthermore, in the comparison segments, the asking price, asking rent, and market information useful for applying the comparison between the segments with the RSA (Equations (8) and (9)) and arriving at the evaluation synthesis (Equation (15)) were collected.

In the different comparison segments, only the asking prices and asking rents useful for making an estimative comparison with the segment to which the avocado cultivation being estimated belonged were considered. They were, therefore, selected to allow an orderly comparison between each segment and the avocado cultivation with respect to the characteristics previously mentioned (location, surface area, age for bioeconomic cycle stage, and farming regime; Table 8 and Table 9).

Table 8.

Asking price in the comparison segments.

Table 9.

Asking rent in comparable segments.

The market analysis was carried out with the collaboration of local market operators (real estate agents, brokers, and other professional operators), which made it possible to carry out appropriate checks on the data acquired and to eliminate unreliable data and information.

However, it should be underlined that the use of such data occurs in relative terms, through their mutual relationships, and not in absolute terms. The RSA is in fact aimed at remote research of the capitalization rate and not at the definition of an estimative function to be used for determining the value through market-oriented approaches. The principle taken into account is that the difference in price or rent fees is explained by the difference found in the characteristics. The adjustments made, therefore, concern the characteristics of the segments used in the comparison, and not the capitalization rate.

Following the valid comparison options for each characteristic between the segment to which the asset to be estimated belongs (the avocado fruit orchard) and the comparable segments (Table 10), the adaptations to be used to determine the correct average price and the correct average rent of the goods were measured.

Table 10.

Comparison characters for the estimated comparison between the segments.

In particular, from the comparison between the asking prices detected in the avocado segment with those detected in similar comparison segments, for each of the characteristics considered, the adaptation coefficients expressed in terms of relative percentage divergence were calculated (Equations (4) and (5); Table 11).

Table 11.

Determination of adaptation coefficients for each comparable segment.

These coefficients are useful for the application of Equations (11) and (14), using which the prices and rental fees detected in each comparable segment were brought into line with the segment to which the asset to be estimated belonged.

The values of these coefficients, being obtained from comparisons between asking prices and market prices, appeared conditioned by inevitable limitations; however, in addition to being identifiable, they are less random than the subjective changes adopted on the capitalization rate by the appraiser on the basis of his own beliefs.

Prices and rental fees of the comparison segments aligned with the avocado segment are, therefore, presented in Table 12.

Table 12.

Prices and rental fees of the comparison segments modified.

The GRM of the avocado segment derived from the available comparison segments could then be calculated as the expected value of prices and incomes adjusted by the fit coefficients used, as follows (Equation (15)):

Consequently, the rate to be used in the capitalization estimate of income from avocado cultivation was equal to 0.03736.

To apply the income capitalization, as indicated by the best practices (Italian Property Valuation Standard 2018; d’Amato and Bambagioni 2023), the cash flow of the avocado cultivation to be estimated was, therefore, determined (Table 13).

Table 13.

Estimated cash flow of avocado fruit orchard (average values).

The estimated cash flow of the avocado plantation under consideration refers to 2022 and was determined assuming a duration of the cultivation cycle of 30 years. The data used were acquired through specific surveys carried out among sector operators, technicians, and professionals and on the basis of market indications provided by the owner of the fruit orchard.

Avocado trees began to yield in the third year, but the highest cash flow was achieved from the 10th year. Revenues were calculated based on an average selling price of EUR 1.5 per ton. The highest cost was for planting expenses (EUR 13,000). At the productive maturity stage, the average annual cost was approximately EUR 6500 per hectare. Labor, packing, and transportation represent the highest expenses, accounting for about 30 percent of the total costs, respectively, followed by farming operations (about 19%). Annual average cost values amounted to approximately EUR 5200 per hectare, with labor accounting for a variation between 28% and 33% and packing and transportation between 30% and just under 32%.

According to the appraisal best practice (Italian Property Valuation Standard 2018), having determined the cash flow of the avocado cultivation, using the capitalization rate derived from the use of the RSA, the NPV was calculated (Equation (20), where n = 30). The value of the fruit orchard when n = 0 was also calculated by discounting the NPV, assuming that it was an infinite and periodic income (V0). The value of the avocado fruit orchard at the time of the estimate (Equation (21), where m = 9) was also obtained, which was equal to EUR 45,170.17 (Table 14).

Table 14.

Values estimated with the capitalization of income.

The value estimated with the RSA was significantly lower than that obtained through the market approach, in which asking prices were used to replace real market prices (Table 4 and Table 5). Furthermore, the value estimated with the RSA appeared more realistic and appropriate, even when compared with other applications conducted in other territories. The market value estimated by the RSA was the second-best solution from an estimative point of view. It was conditioned by the use of a capitalization rate derived from a comparison between segments and, in particular, by the use of asking prices, asking rent, and market quotations. Even in the presence of these limitations, it still appeared less random than what can be obtained by relying exclusively on the expertise of the appraiser.

With reference to the case study, therefore, it seems that the hypothesis of replacing market prices with asking prices is not a reliable choice, particularly in the case of the valuation of agricultural land, where there are various difficulties in obtaining comparative data on land similar to that to be valued due to the heterogeneity of its intrinsic characteristics, which can cause various inconveniences in carrying out the valuation (DeWeese 2022). Furthermore, by making use of the adjustments to be made on the primary quantities from which the capitalization rate was obtained, it seems that the RSA is capable of attenuating the distorting effects of asking prices and market quotations on the estimated value. Even in the absence of comparison prices and incomes, from the case study it seems that it is possible to perform an adequate and acceptable appraisal of the market value. The value estimated following the RSA procedure seems capable of representing the market value of the avocado fruit orchard, as detectable with some available quotations (Exeo 2023). However, it is necessary to highlight the need to carry out further applications in order to more effectively validate this initial evidence. In this regard, it should be noted that approximate or partially reliable market information can influence the estimated value, as the adjustments made in the comparison between segments can depend on it. It is, therefore, necessary to use them with caution. Knowledge of the market and the expertise of the appraiser are, therefore, also essential with reference to the use of the RSA. For these reasons, the RSA cannot be interpreted as a simplification or an alternative to market-oriented approaches or the income approach.

Furthermore, the possibility of determining the capitalization rate by comparing segments involves acting on the characteristics of the segments and not making positive or negative variations on the rate, in a random and subjective way, on the part of the evaluator.

The use of the MCS, therefore, requires similar skills to those of other estimation procedures in terms of competence and professionalism by the appraiser and cannot be assimilated to an ambiguous estimation procedure. On the other hand, the lack of comparison data cannot constitute a facilitation to withdraw from the formulation of an appropriate comparison function (Parker 2016).

6. Concluding Remarks

This paper proposed the possibility of employing the asking price in the comparison between the segment of the fruit orchard to be valuated and other comparable segments. The aim was to derive the rate to be used in the capitalization of the income expected from the cultivation of the land to be valued.

The results showed the effectiveness of the RSA in two useful directions: the possibility of exploiting extra data and market information for estimative purposes without using the asking price in market-oriented procedures, and the possibility of preventing the use of the expert’s expertise with reference to the choice of the capitalization rate. The rate, in fact, is determined by comparison between segments close to that of the asset being valued and not on the basis of investments considered alternative, or on the basis of subjective beliefs of the appraiser.

In the absence of comparative prices and incomes, even in the presence of the limitations referred to, the RSA could, therefore, constitute a valid aid for estimating the market value of agricultural land in the absence of other possible alternatives, i.e., it is preferable because it can allow one to “be more or less right than precisely wrong”.

In the presence of limitations that prevent the application of market-oriented approaches, the RSA, through the formulation of a comparison function between different market segments, can represent a valid aid to develop an estimate judgment. In this regard, the case study verified the possibility of using extra data and asking prices in the comparison between segments, in compliance with the principle of comparison and consistent with the foundations of appraisal theory.

In the absence of adequate knowledge of the reference market (market segment of the asset to be estimated and comparison segments), however, the application of the RSA can lead to results no less random than what could occur by resorting solely to the appraiser’s expertise. The RSA cannot, therefore, be understood as instrumental to the use of asking prices directly in the comparison function of the market-oriented approach.

The use of the RSA, allowing the GRM from which to derive the capitalization rate to be determined, takes place, in fact, in compliance with the estimation principles and the indications of the evaluation standards (TEGoVA 2020).

In this regard, it is possible to note some aspects of compliance with the valuation standards. A first element concerns the logic of the RSA, substantially similar to that used for the remote search of the rate in the estimate for direct capitalization (Italian Property Valuation Standard 2018). The comparison between segments also requires an accurate and in-depth market investigation, as indicated by the IVS, and it is advisable that it takes place in compliance with the indications contained in the reference best practices.

Furthermore, through the estimate of the GRM, the RSA imposes the need to determine an appropriate cash flow, helping to make the estimate of the asset value compliant with transparency and replicability requirements, consistent with the estimation methodology and valuation standards (Italian Property Valuation Standard 2018).

Therefore, although it is based on the use of extra data and market information, the RSA is more in line with the estimation methodology than to what occurs when determining the estimated value from the market comparison with the asking prices or by resorting solely to the appraiser’s expertise.

Even in the estimation of agricultural land, the limited availability of market comparison data can justify the use of the RSA, but even in this context, its use can only occur in the presence of adequate knowledge of the market segment of the land to be estimated and of the comparison segments. The peculiar characteristics of the land market also make it indispensable for the use of the RSA to resort to an integration of the real estate data with in-depth checks and feedback by the appraiser. Although conditioned by the limitations caused by the unavailability of real estate data of comparison assets, the RSA made it possible to determine the value of the fruit orchard being estimated by adopting a procedure consistent with the comparison between different segments, which was verifiable and capable of containing uncertainty of a subjective and unverifiable judgement.

However, the MCS cannot be understood in any way as an alternative approach to market-oriented procedures. It is possible, rather, to envisage its use also to integrate applications carried out with other estimating approaches, or to envisage its use as a verification and comparison tool also when reviewing estimates.

It should also be considered that the growing availability of extra data and market information can constitute an area of interest for studies and research of an estimative nature for other reasons, too. Among these, we highlight the possibility of carrying out analyses with georeferenced data (Giuffrida et al. 2023) both in local and large-area territorial contexts, or integrating modern estimation technologies (Salvo 2023; Tajani et al. 2020); for example, to evaluate the weight assumed by the various relevant variables on the expected value of market prices (Salvo et al. 2023) and on the price and income adjustments expected by the RSA.

Another element worthy of further investigation is also represented by the opportunity to verify the market values estimated with MCS compared to the final sale prices of real estate.

In conclusion, regarding missing comparable data, the results obtained here showed that the RSA can be useful to estimate the market value. RSA can also be used to verify or control an estimate judgment already made. Further application possibilities can also be found in counseling activities for the benefit of subjects interested in operating in the real estate investment sector, since, in the absence of necessary comparison data, through the application of the RSA it is possible to acquire useful indications for operating with greater awareness among possible alternative investments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C.; methodology, G.C.; software, G.C. and M.C.; validation, G.C. and L.G.; formal analysis, G.C. and M.C.; investigation, G.C.; resources, G.C.; data curation, G.C. and L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C. and L.G.; writing—review and editing, G.C., M.C. and L.G.; visualization, G.C. and M.C.; supervision, G.C.; project administration, G.C.; funding acqusisition, G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the research project PIAno di inCEntivi per la RIcerca di Ateneo 2020/2022 (PIACERI)–UNICT LINE 2-2020/2022-Sostenibilità ed innovazioni della ricerca in agricoltura, alimentazione e ambiente, funding by the University of Catania.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Another similarity distance is the Manhattan distance, which is equivalent to the distance one needs to travel in a Cartesian plane to move from one point i to another point j by moving in directions parallel to the axes (. Together with the Euclidean distance, it can be derived from the more general Minkowski distance of order k between units i and j: , where k ≥ 1. If k = 2, one obtains, in fact, the Euclidean distance, and with k = 1, the Manhattan distance. |

| 2 | Estimated costs included the average planting cost, distinguished into its different components (such as deep tillage, plants and plant setting, etc.), and direct costs, excluding taxes. Direct costs encompass farming operations (such as soil tillage, fertilization, pesticide treatments, etc.), performed considering rental usage, labor for all manual operations (pruning, harvesting, etc.), and boxes and transportation, as the harvested production is sold to the local wholesale market. |

References

- Albrecht, James, Pieter Gautier, and Susan Vroman. 2016. Directed search in the housing market. Review of Economic Dynamics 19: 218–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglin, Paul M., Ronald Rutheford, and Thomas M. Springer. 2003. The trade-off between the selling price of residential properties and time-on-market: The impact of price setting. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 26: 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, Leonardo, Enrico Marone, and Gabriele Scozzafava. 2023. La scuola estimativa italiana, gli International Valuation Standard (IVS) e il Codice delle valutazioni immobiliari: I problemi di natura metodologica e applicativa. Aestimum 83: 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centro di ricerca Politiche e Bioeconomia (Crea). 2024. L’agricoltura in Sicilia in cifre 2024. p. 109. ISBN 9788833853796. Available online: https://www.crea.gov.it (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Corine Land Cover (CLC). 2018. CORINE Land Cover (Vector/Raster 100 m), Europe, 6-Yearly, DOI (Raster 100 m). Available online: https://doi.org/10.2909/960998c1-1870-4e82-8051-6485205ebbac (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- d’Amato, Maurizio, and Giampiero Bambagioni. 2023. Discounted Cash Flow Analysis and Prudential Value DCFA Formula. Aestimum 83: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Amato, Maurizio, and Giuseppe Cucuzza. 2022. Cyclical capitalization: Basic models. Aestimum 80: 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Amato, Maurizio, Giuseppe Cucuzza, and Giampiero Bambagioni. 2023. Appraising forced sale value by the method of short table market comparison approach. Aestimum 82: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWeese, Gary S. 2022. Land Valuation: Real Solutions to Complex Issues. Chicago: The Appraisal Institute, p. 194. ISBN 9781935328865. [Google Scholar]

- Exeo. 2023. Osservatorio dei valori agricoli. Padova: Rapporto Statistic. ISBN 978-88-6907-335-9. Available online: www.exeo.it (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Giuffrida, Laura, Giuseppe Cucuzza, Daniela Tavano, Francesca Salvo, and Maria De Salvo. 2024. Using a spatial econometric approach to detect main determinants and spillover effects of residential property prices in Spezia Italy. Paper presented at the International Symposium “Networks, Markets & People”, University of Reggio Calabria, Reggio Calabria, Italy, May 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, Laura, Maria De Salvo, Andrea Manarin, Damiano Vettoretto, and Tiziano Tempesta. 2023. Exploring farmland price determinants in Northern Italy using a spatial regression analysis. Aestimum 83: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, Edward E., and Charles Nathanson. 2017. An extrapolative model of house price dynamics. Journal of Financial Economics 126: 147–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glower, Michel, Donald R. Haurin, and Patrich H. Hendershott. 1998. Selling time and selling price: The influence of seller motivation. Real Estate Economics 26: 719–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohl, Niklas, Peter Haan, Claus Michelsen, and Felix Weinhardt F. 2024. House price expectations. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 218: 379–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacıevliyagil, Nuri, Krzysztof Drachal, and Ibrahim Halil Eksi. 2022. Predicting House Prices Using DMA Method: Evidence from Turkey. Economies 10: 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Lu, and William Strange. 2016. What is the role of the asking price for a house? Journal of Urban Economics 93: 115–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haurin, Donald, Jessica L. Haurin, Taylor Nadauld, and Anthony Sanders. 2010. List prices sale prices and marketing time: An application to U.S. housing markets. Real Estate Economics 38: 659–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, Etika, Iwan Rudiarto, F. Siegert, and W. D. Vries. 2018. Modeling the Dynamic Interrelations between Mobility, Utility, and Land Asking Price. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 123: 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Valuation Standards Council (IVS). 2022. International Valuation Standards. Effective 31 January 2022. Norwich: Page Bros. ISBN 978-0-9931513-4-7. [Google Scholar]

- Isakson, Hans R. 1986. The Nearest Neighbors Appraisal Technique: An alternative to the Adjustment Grid Methods. Real Estate Economics 14: 175–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Property Valuation Standard. 2018. Codice delle Valutazioni Immobiliari, 5th ed. Roma: Tecnoborsa S.c. p.a. Consorzio per lo Sviluppo del Mercato Immobiliare Editore, p. 370. ISBN 9788894315806. [Google Scholar]

- Khezr, Peyman, and Flavio M. Menezes. 2016. Dynamic and Static Asking Prices in the Sydney Housing Market. The Economic Record 92: 209–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, John R. 2002. Listing price, time on market, and ultimate selling price: Causes and effects of listing price changes. Real Estate Economics 30: 213–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Nan. 2021. Market buoyancy, information transparency and pricing strategy in the Scottish housing market. Urban Studies 58: 3388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganelli, Benedetto, Francesco Paolo Del Giudice, and Debora Anelli. 2022. Analysis of the difference Between Asking Price and Selling Price in the Housing Market. Paper presented at the 22nd International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications (ICCSA 2022), Malaga, Spain, July 4–7, vol. 13378, pp. 629–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michieli, Maurizio, and Giovanni Battista Cipollotti. 2018. Trattato di Estimo. Bologna: Edagricole, New Business-Media, p. 698. ISBN 9788850655274. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, David. 2016. International Valuation Standards: A Guide to the Valuation of Real Property Assets. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, p. 272. ISBN 978-1-118-32936-8. [Google Scholar]

- Salvo, Francesca. 2023. From appraisal function to Automatic Valuation Method (AVM). The contribution of International Valuation Standards in modern appraisal methodologies. Aestimum 83: 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvo, Francesca, Manuela De Ruggiero, and Daniela Tavano. 2023. Social Variables and Real Estate Values: The Case Study of the City of Cosenza. In Green Energy and Technology. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 173–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonotti, Marco. 1985. La comparazione e il sistema generale di stima. Rivista di Economia agraria XL 4: 543–561. [Google Scholar]

- Simonotti, Marco. 1987. Esposizione diagrammatica del sistema generale di stima. Rivista di Economia Agraria XLII 1: 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Simonotti, Marco. 1989. Applicazioni del Sistema Generale di Stima. Rivista di Economia Agraria XLIV 3: 505–12. [Google Scholar]

- Simonotti, Marco. 2003. Il saggio di capitalizzazione negativo nella stima analitica degli arboreti. Aestimum 43: 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Simonotti, Marco. 2006. Metodi di stima immobiliare. Applicazione degli standard internazionali. Palermo: Flaccovio editore, p. 425. ISBN 9788877586865. [Google Scholar]

- Simonotti, Marco. 2011. Ricerca del saggio di capitalizzazione nel mercato immobiliare. Aestimum 59: 171–80. [Google Scholar]

- Simonotti, Marco. 2019. Valutazione Immobiliare Standard. Nuovi metodi. Mantova: Stimatrix editore, p. 576. ISBN 978-88-904764-6-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tajani, Francesco, Pierluigi Morano, Francesca Salvo, and Manuela De Ruggiero. 2020. Property valuation: The market approach optimised by a weighted appraisal model. Journal of Property Investment and Finance 38: 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TEGoVA. 2020. European Valuation Standards, 9th ed. Brussels: TEGoVA, p. 400. ISBN 9791220092913. [Google Scholar]

- Tempesta, Tiziano. 2018. Appunti di Estimo Rurale. Padova: Cleup, p. 316. ISBN 978 88 6787 888 8. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, Riccardo, Salvatore Tudisca, Giorgio Schifani, Anna Maria Di Trapani, and Giuseppina Migliore. 2018. Tropical Fruits as an Opportunity for Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: The Case of Mango in Small-Sized Sicilian Farms. Sustainability 10: 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węgrzyn, Joanna, and Julita Kuta. 2024. The effect of anchoring bias on the estimation of asking and transaction prices in the housing market. Real Estate Management and Valuation 32: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yanbing, Xiuping Hua, and Liang Zhao. 2012. Exploring determinants of housing prices: A case study of Chinese experience in 1999–2010. Economic Modelling 29: 2349–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).