Abstract

Amid Lebanon’s multifaceted economic crisis, this paper explores the intricate dynamics between political patronage networks and financial stability. Grounded in the theoretical frameworks of New Institutional Economics (NIE) and Project Management (PM), the study delves into how entrenched political elites and patronage networks have shaped Lebanon’s financial system, exacerbating vulnerabilities and perpetuating the ongoing crisis. Utilizing qualitative methods including in-depth interviews, document analysis, and case studies, the research illuminates the pivotal role of political actors and their vested interests in economic policies and financial institutions. The findings reveal systemic governance failures, crony capitalism, and institutional decay as underlying causes of Lebanon’s economic stress. In response, the paper proposes a comprehensive framework for governance reform that integrates insights from NIE and PM, emphasizing structured planning, accountability mechanisms, and institutional strengthening. The purpose of this study is not only to contribute to a nuanced understanding of Lebanon’s challenges but also to offer actionable insights for policymakers, academics, and stakeholders to address the root causes of the crisis and pave the way for sustainable economic recovery and revitalization.

1. Introduction

The economic landscape of Lebanon stands at a critical juncture, marred by a profound crisis that has reverberated across its financial institutions, societal structures, and political frameworks (World Bank 2021). At the heart of Lebanon’s economic woes lie deeply entrenched political patronage networks, which have wielded considerable influence over the nation’s financial stability and governance structures (MayBaaklini 2023).

Political patronage networks, characterized by intricate webs of relationships and exchanges of favors among political elites, business magnates, and other vested interests, have long shaped Lebanon’s socio-political landscape (MayBaaklini 2023). These networks, rooted in historical legacies and perpetuated by entrenched power structures, have not only perpetuated systemic inequalities but have also played a pivotal role in steering economic policies and financial decisions (Maya Gebeily 2024).

These networks originated during the Ottoman era, where local leaders, or “zaims”, wielded substantial influence by leveraging their connections and dispensing favors to maintain control over their constituencies (Johnson 1986) This system was perpetuated during the French Mandate period, further entrenching patronage as a central mechanism of political power (Hourani 1991). Then, following Lebanon’s independence in 1943, the sectarian nature of its political system institutionalized patronage networks, intertwining them with the country’s confessional divisions (Makdisi 2000). Political elites utilized their sectarian affiliations to mobilize support, secure resources, and consolidate power, leading to a complex web of mutual dependencies and reciprocal obligations that continue to dominate Lebanese politics today (Makdisi 2000).

Comparing Lebanon’s patronage networks with those in other countries, like Iraq, Syria, and Jordan, highlights similar patterns of political control through patron–client relationships. In Iraq and Syria, sectarian and tribal affiliations are crucial for political stability, while Jordan’s monarchy uses patronage to manage tribal allegiances (Luciani 1990). This comparative analysis underscores the systemic nature of political patronage in shaping governance and economic development in the region (Luciani 1990).

The significance of understanding political patronage networks within the context of Lebanon’s economic crisis cannot be overstated. The critical impact of political stability and governance on financial and economic development underscores the necessity of stable and transparent political institutions to foster economic growth and financial stability. Studies by Girma and Shortland (2008) and Chletsos and Sintos (2024) highlight the significant influence of political regime type and stability on financial development, while research by Das and Das (2014) and Das and Mandal (2022) emphasizes the importance of governance and anti-corruption measures for sustainable economic growth. As Lebanon faces a severe financial downturn exacerbated by political instability, corruption, and mismanagement, the influence of these networks looms large over efforts to mitigate the crisis and chart a path towards recovery.

This qualitative study seeks to unravel the complex interplay between political patronage networks and financial stability in Lebanon. Through an in-depth exploration of the mechanisms through which these networks operate, the paper aims to shed light on the underlying dynamics that have precipitated and perpetuated Lebanon’s economic crisis.

By employing a multifaceted approach encompassing interviews, document analysis, and case studies, this study endeavors to offer nuanced insights into the role of political actors, the interconnectedness of political and financial interests, and the governance challenges posed by entrenched patronage networks. Moreover, it seeks to delineate the implications of these dynamics for Lebanon’s financial stability, investor confidence, and prospects for reform.

This study addresses the gap in the existing literature, where practical policy recommendations are often lacking despite discussions of the challenges posed by political patronage. By utilizing New Institutional Economics (NIE) and Project Management (PM) methodologies, the study offers actionable policy measures, evaluates their effectiveness, and provides tailored solutions considering Lebanon’s unique economic context.

Amid Lebanon’s economic crisis, this study explores political patronage, corruption, and crony capitalism. Integrating theories from New Institutional Economics (NIE) and Project Management (PM), it examines how political elites shape the financial system, exacerbating vulnerabilities. The integration of Project Management (PM) alongside New Institutional Economics (NIE) in this study is based on the practical application of PM principles in managing large-scale economic reforms and governance projects. PM offers systematic methodologies for planning, risk management, and performance evaluation, which are crucial for the successful implementation of economic policies.

Using qualitative methods like interviews and case studies, the research dissects the role of political actors in economic policies. This approach informs policy discourse and collective action for governance reform and economic recovery, aiming to foster inclusive development.

In the ensuing sections, we delve into the complexities of Lebanon’s economic crisis, examine the functioning of political patronage networks, analyze case studies highlighting their impact on financial stability, and elucidate the challenges and implications that emanate from their pervasive influence. Through this inquiry, our motivation is to offer actionable recommendations, chart future research directions, and foster a more informed discourse on the critical issues confronting Lebanon today.

2. Literature Review

The impact of political issues and stability on financial stability and development has been a subject of considerable interest among researchers. Understanding how political regimes and stability influence financial markets and economic growth is crucial for policymakers and scholars alike. Recent studies have delved into the intricate relationship between political institutions, regime characteristics, and the pace of financial development.

A study conducted by Girma and Shortland (2008) indicates that the type of political regime significantly affects the speed of financial development. Autocratic regimes are less likely to establish robust financial markets, while more representative, democratic political systems tend to promote faster financial development. The study suggests that financial development is influenced more by regime characteristics than by the legal system.

Another study by Chletsos and Sintos (2024) emphasizes the crucial role of political stability in influencing financial development, particularly in the context of 123 countries studied from 1980 to 2017. It reveals that political stability positively correlates with financial development, fostering confidence among economic agents and facilitating the implementation of liberalization reforms. Structural conditions, which have been identified as generators of long-term inequality, are empirically supported as exogenous determinants of political instability. Moreover, political instability, driven by conditions perpetuating inequality and weak democracy, poses a significant challenge for international organizations like the World Bank striving to promote financial development. The study’s findings underscore the importance of political stability for financial development and highlight the critical pathway from structural inequality to political instability, particularly in non-democratic settings, and then to financial underdevelopment (Chletsos and Sintos 2024).

Furthermore, the studies by Das and Das (2014) and Das and Mandal (2022) provide critical insights into the interrelationships between governance, corruption, and key economic indicators. Das and Das (2014) found that governance significantly affects economic growth, with pooled data showing that business and consumer confidence indices, unemployment, debt ratio, and governance are key determinants of growth. Notably, governance coefficients were negative, suggesting potential non-linear effects, emphasizing the need to explore various aspects of governance. Das and Mandal (2022) further explored the dynamics between corruption and inflation. Their study, covering 30 countries from 1996 to 2017, found a long-run equilibrium relationship between corruption control and inflation rates. They observed both long-run and short-run causality from corruption to inflation, highlighting the importance of implementing stricter anti-corruption measures to reduce inflation and enhance social sustainability.

These findings collectively underscore the critical impact of political stability and governance on financial and economic development, highlighting the need for stable and transparent political institutions to foster economic growth and financial stability.

Lebanon has a complex political system that has elements of both democracy and authoritarianism. While it is considered to have democratic institutions, such as free elections and a parliamentary system, the political landscape is heavily influenced by sectarian divisions and patronage networks, which often lead to political deadlock and inefficiency (El-Husseini and Crocker 2012). Additionally, certain aspects of governance have been criticized for being authoritarian, particularly in terms of the influence of powerful political figures and the limited accountability of the ruling class (Salamey 2013). Therefore, it would be more accurate to describe Lebanon as a country with a hybrid political system rather than purely autocratic.

2.1. Defining Political Patronage Networks

Political patronage networks represent complex webs of relationships and exchanges of favors among political elites, business figures, and other influential actors within a society (Towett and Ndungu Kungu 2020; Thomsen and Fakhoury 2022). In Lebanon, these networks have evolved over decades, intertwining with the country’s socio-political fabric and exerting substantial influence over its economic landscape (Fahed-Sreih 2023).

At their core, political patronage networks operate on the basis of reciprocal obligations and mutual dependencies. Political elites, often holding positions of power or influence, leverage their connections to secure economic advantages, maintain political dominance, and consolidate their hold on key institutions and resources (Paniagua and Vogler 2022). In return, they dispense favors, appointments, and privileges to their allies, thereby reinforcing loyalty and perpetuating their own power structures (Brinkerhoff and Goldsmith 2002).

The modus operandi of political patronage networks in Lebanon is multifaceted, encompassing a spectrum of practices ranging from informal alliances and backroom deals to overt displays of influence and coercion. These networks thrive on lack of transparency, uncertainty, and the exploitation of institutional weaknesses, often operating beyond the purview of formal mechanisms.

Moreover, political patronage networks in Lebanon are deeply entrenched within the country’s sectarian and confessional dynamics, further complicating the already intricate tapestry of Lebanese politics. Sectarian affiliations and communal identities serve as conduits for the consolidation of patronage networks, with political leaders often leveraging religious affiliations to mobilize support and gain legitimacy (Kingston 2013).

The pervasiveness of political patronage networks extends beyond the realm of politics, permeating various spheres of Lebanese society, including business, academia, and civil society (Allison McCulloch 2022). In the economic domain, patronage networks wield significant influence over investment decisions, regulatory frameworks, and market dynamics, shaping the allocation of resources and the distribution of wealth in ways that perpetuate inequality and hinder sustainable development.

Understanding the dynamics of political patronage networks is indispensable for grasping the root causes of Lebanon’s economic crisis. These networks, by virtue of their reach and influence, have played a central role in shaping monetary policies and economic policies, distorting market mechanisms, and perpetuating systemic vulnerabilities. As Lebanon confronts the formidable challenges posed by its economic downturn, the need to unravel the complexities of political patronage networks becomes even more pressing.

In the subsequent sections of this study, we delve deeper into the functioning of political patronage networks in Lebanon, examining their role in economic decision making, their impact on financial stability, and the challenges they pose to governance and reform efforts. Through a comprehensive analysis, we endeavor to elucidate the intricate interplay between political patronage and Lebanon’s economic crisis, offering insights that can inform policy discourse, academic inquiry, and collective action aimed at charting a path towards recovery and revitalization.

2.2. Understanding Crony Capitalism and Its Implications for Lebanon

Crony capitalism refers to a system where economic activities are heavily influenced by political power, shaping which firms operate, the resources they utilize, and the investments they undertake (Abdo et al. 2020). In such systems, political connections play a crucial role, with firms often relying on these connections for survival and success (Acemoglu and Verdier 2000). This phenomenon is particularly prevalent in developing countries, where business activities are often conducted based on “deals” rather than clear rules and regulations. Instances of crony capitalism have been documented in various countries, including Egypt under the Mubarak regime (Osman 2013) and China (Jargad 2022), where political connections to local governments are almost prerequisites for business success. Despite its prevalence, measuring the extent of crony capitalism globally remains a challenge.

Lebanon’s economic landscape has not been immune to the influence of crony capitalism. The intertwining of political and economic interests has resulted in certain sectors being dominated by politically connected individuals and entities (Brown-Jackson et al. 2019). For instance, the electricity sector in Lebanon has been subject to significant corruption and inefficiency, with political elites using state resources to benefit themselves and their supporters (Diwan 2019). The prevalence of crony capitalism exacerbates economic inequalities, stifles competition, and undermines the country’s economic development efforts (Harb 2006). As Lebanon grapples with its economic crisis, addressing the systemic issues associated with crony capitalism is essential for promoting transparency, accountability, and sustainable economic growth.

2.3. New Institutional Economics (NIE)

Political patronage networks, a focal point of New Institutional Economics (NIE), represent intricate systems of relationships and exchanges among political elites, business figures, and influential actors within Lebanese society. NIE offers a unique lens through which to analyze these networks, emphasizing their role in shaping economic outcomes and institutional structures (Natsvaladze 2023). One of the key advantages of applying NIE to the Lebanese context lies in its ability to elucidate the interplay between informal institutions, such as patronage networks, and formal institutions, like government policies and regulations.

In Lebanon, where political patronage networks have deep historical roots and wield considerable influence over economic decisions, NIE provides a framework to understand the mechanisms through which these networks operate. By emphasizing the importance of incentives, property rights, and transaction costs, NIE sheds light on how political elites leverage their connections to secure economic advantages and maintain power (Dixit 2002). Moreover, NIE highlights the impact of patronage networks on market dynamics, resource allocation, and wealth distribution, elucidating their role in perpetuating inequality and hindering sustainable development.

Furthermore, NIE underscores the importance of institutional analysis in understanding the complexities of Lebanon’s economic crisis. By examining the formal and informal rules that govern economic interactions, NIE enables researchers and policymakers to identify areas where institutional reforms are needed to address the root causes of the crisis (Azfar 2002). In particular, NIE emphasizes the importance of reducing transaction costs, improving property rights enforcement, and enhancing institutional transparency and accountability.

In summary, applying NIE to the study of political patronage networks in Lebanon offers several advantages. It provides a theoretical framework to understand the incentives and behaviors of political elites, elucidates the impact of patronage networks on economic outcomes, and identifies avenues for institutional reform. By incorporating insights from NIE into policy discourse and academic inquiry, stakeholders can work towards addressing the challenges posed by political patronage and charting a path towards economic recovery and revitalization in Lebanon.

2.4. Theoretical Justification of Interrelationships

This study is theoretically anchored in New Institutional Economics (NIE), complemented by insights from economic theories, to elucidate the complex interrelationships among governance, corruption, and economic development.

- 1.

- Institutional Environment and Political Patronage

The institutional environment significantly influences the prevalence and functioning of political patronage networks. Institutions characterized by weak governance structures, lack of transparency, and inadequate rule of law are more susceptible to the proliferation of patronage networks. Therefore, it is theoretically expected that a weak institutional environment would be positively correlated with the presence and extent of political patronage (North 1990; Rose-Ackerman 1999).

- 2.

- Rule of Law and Corruption Levels

The rule of law is a fundamental determinant in shaping the levels of corruption within a society. A strong rule of law, marked by impartial enforcement of laws and contracts, tends to reduce opportunities for corrupt practices. Hence, it is theoretically expected that a higher level of the rule of law will be associated with lower levels of corruption (Kaufmann et al. 2010; Treisman 2000).

- 3.

- Corruption Levels and Economic Development

Corruption has been widely acknowledged as a significant barrier to economic development. High levels of corruption lead to misallocation of resources, reduced investment, and inefficiency in economic activities. Therefore, it is theoretically anticipated that higher levels of corruption will be negatively correlated with economic development indicators, such as GDP growth, investment levels, and human development (Mauro 1995) (Acemoglu et al. 2001).

- 4.

- Political Patronage and Economic Development

Political patronage, by diverting resources away from productive uses to politically connected individuals or groups, can hinder economic development (Auyero et al. 2009). It is expected that high levels of political patronage will be associated with lower economic growth, decreased investment, and reduced human development outcomes.

- 5.

- Institutional Environment and Economic Development

The institutional environment plays a crucial role in fostering or constraining economic development (Acemoglu et al. 2001). Strong institutions characterized by transparency, accountability, and the rule of law tend to create an environment conducive to economic growth and development (Kaufmann et al. 2010). Therefore, it is theoretically posited that a favorable institutional environment will be positively correlated with economic development indicators.

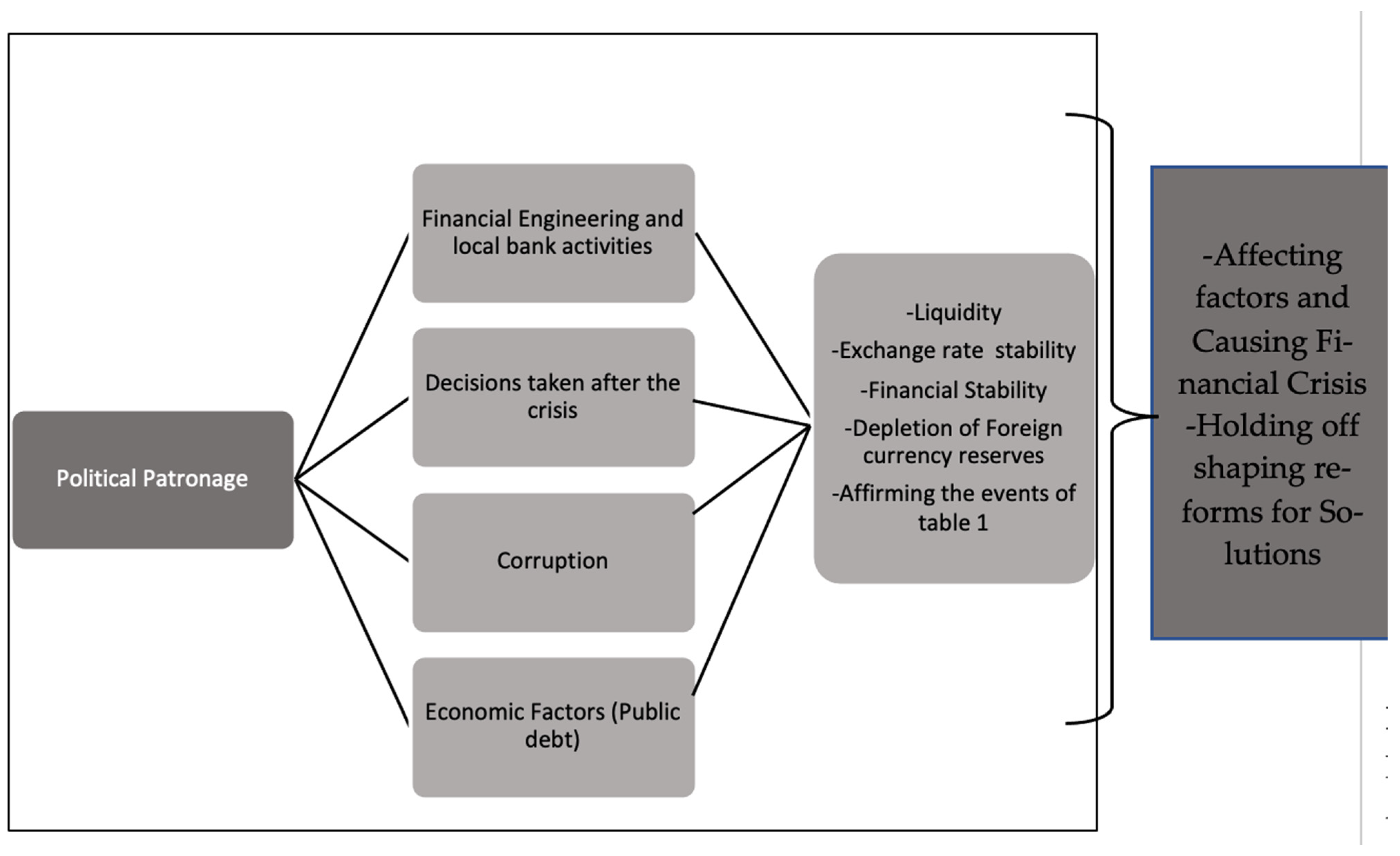

Based on the above theoretical justifications, a theoretical model can be established as follows (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical model, adapted by the authors.

This theoretical model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the interrelationships between the key indicators and forms the basis for our empirical investigations.

2.5. Integrating Project Management, New Institutional Economics, and Economic Theories for Effective Governance Reforms

In contemporary governance paradigms, the amalgamation of Project Management (PM), New Institutional Economics (NIE), and Economic Theories presents a robust framework for fostering impactful reforms. We refer to several case studies and examples where PM methodologies have been effectively integrated into economic policy implementation.

- World Bank Projects: The World Bank often employs PM principles to manage its development projects. For instance, the implementation of infrastructure projects in developing countries requires meticulous planning, stakeholder engagement, and continuous monitoring—core aspects of PM.

- Public Sector Reforms: Many public sector reform initiatives, such as those in the health and education sectors, have utilized PM techniques to ensure successful implementation. These reforms are treated as projects with defined objectives, timelines, and resource allocations.

- Anti-Corruption Programs: In countries like Georgia and Singapore, comprehensive anti-corruption programs have been implemented using PM frameworks. These programs involve setting clear goals, developing detailed action plans, managing resources efficiently, and continuously monitoring progress, all of which are fundamental PM practices.

By integrating PM with NIE, this study leverages the systematic approach of PM to enhance the analysis of economic policy implementation. PM’s focus on structured methodologies for managing complexity, assessing risks, and ensuring accountability complements NIE’s theoretical insights into institutional dynamics. This interdisciplinary approach not only enriches the analytical framework but also provides practical tools for policymakers to design and implement effective governance reforms.

Furthermore, each theory contributes distinct perspectives and methodologies.

- The Keynesian Theory of Aggregate Demand delves into the fluctuations of domestic and foreign demand, shaping economic output and employment dynamics (Foster 2013). Leveraging this theory enables the identification of barriers to project implementation while aligning interventions with prevailing economic conditions.

- The Monetary Approach to the Balance of Payments underscores the critical influence of exchange rates and monetary policies on a nation’s balance of payments (Murad 2022). Deliberate consideration of transaction costs and incentives is paramount for optimizing decision-making processes and resource allocations.

PM can tailor interventions to promote investment and enhance productivity (Quisumbing and Pandolfelli 2010). The integration of PM principles with these theories furnishes governance reforms with systematic planning, precise goal delineation, resource optimization, and robust risk management strategies, thereby enhancing their implementation efficacy (PMBOK Guide 2021). Collectively, this synthesized framework engenders a holistic approach to address governance complexities, instigate institutional transformations, and propel inclusive growth agendas forward.

3. Lebanon’s Economic Crisis

Lebanon’s economic crisis represents a convergence of myriad factors rooted in decades of systemic dysfunction, political instability, and unsustainable economic practices. At its core lies a nexus of interconnected challenges that have precipitated a profound and protracted downturn, testing the resilience of Lebanon’s financial institutions and societal cohesion.

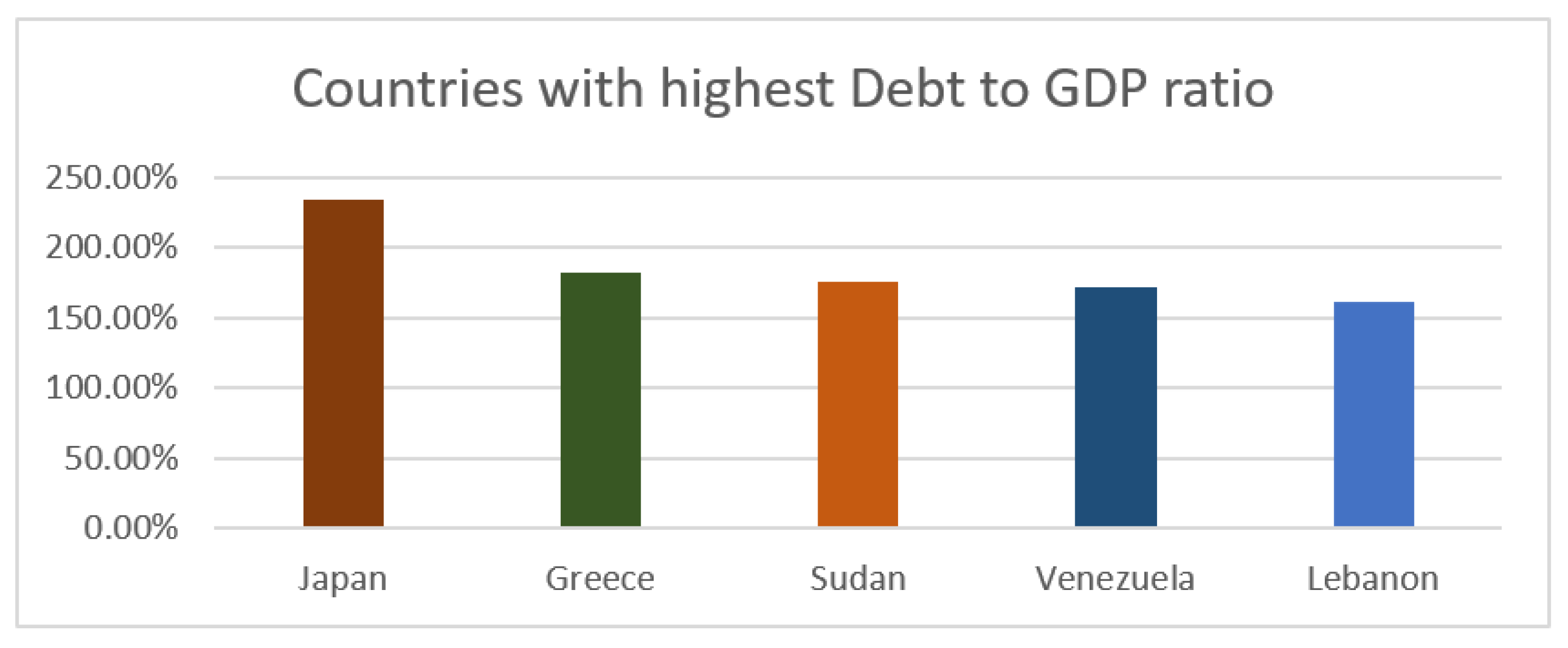

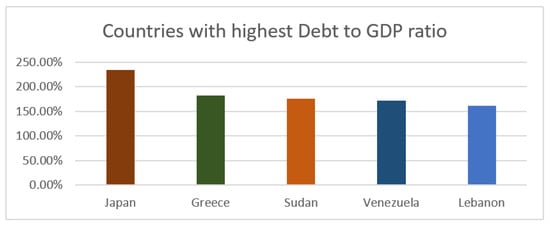

The genesis of Lebanon’s economic crisis can be traced back to a combination of fiscal mismanagement, endemic corruption, and unsustainable debt accumulation. For years, successive governments have pursued expansionary fiscal policies, characterized by heavy borrowing, budget deficits, and a lack of fiscal discipline. The result has been a ballooning public debt, which, as a percentage of GDP, by 2019 stood among the highest in the world, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Countries with highest debt ratios by 2019, adapted by the author. Source: National Debt by Country (2019).

Compounding these fiscal challenges is a pervasive culture of corruption that permeates Lebanon’s public and private sectors. Corruption, manifesting in various forms, such as embezzlement, bribery, and nepotism, has eroded trust in public institutions, undermined the rule of law, and distorted market mechanisms (Abouzeid 2021). The pervasive influence of political patronage networks has further facilitated the entrenchment of corrupt practices, exacerbating governance deficiencies and hindering efforts to combat systemic corruption.

Against this backdrop of fiscal mismanagement and corruption, Lebanon’s economy has been beset by structural imbalances and vulnerabilities. The country’s overreliance on remittances, tourism, and real estate speculation has left it susceptible to external shocks and fluctuations in global markets. Moreover, the lack of diversification and investment in productive sectors has stifled economic growth, perpetuating dependence on unsustainable sources of revenue.

The eruption of socio-political unrest in 2019 further exacerbated Lebanon’s economic woes, precipitating a wave of protests and civil unrest against government corruption, economic inequality, and sectarianism. The subsequent resignation of Prime Minister Saad Hariri and the failure to form a new government underscored the deep-seated political dysfunction that continues to impede meaningful reform efforts.

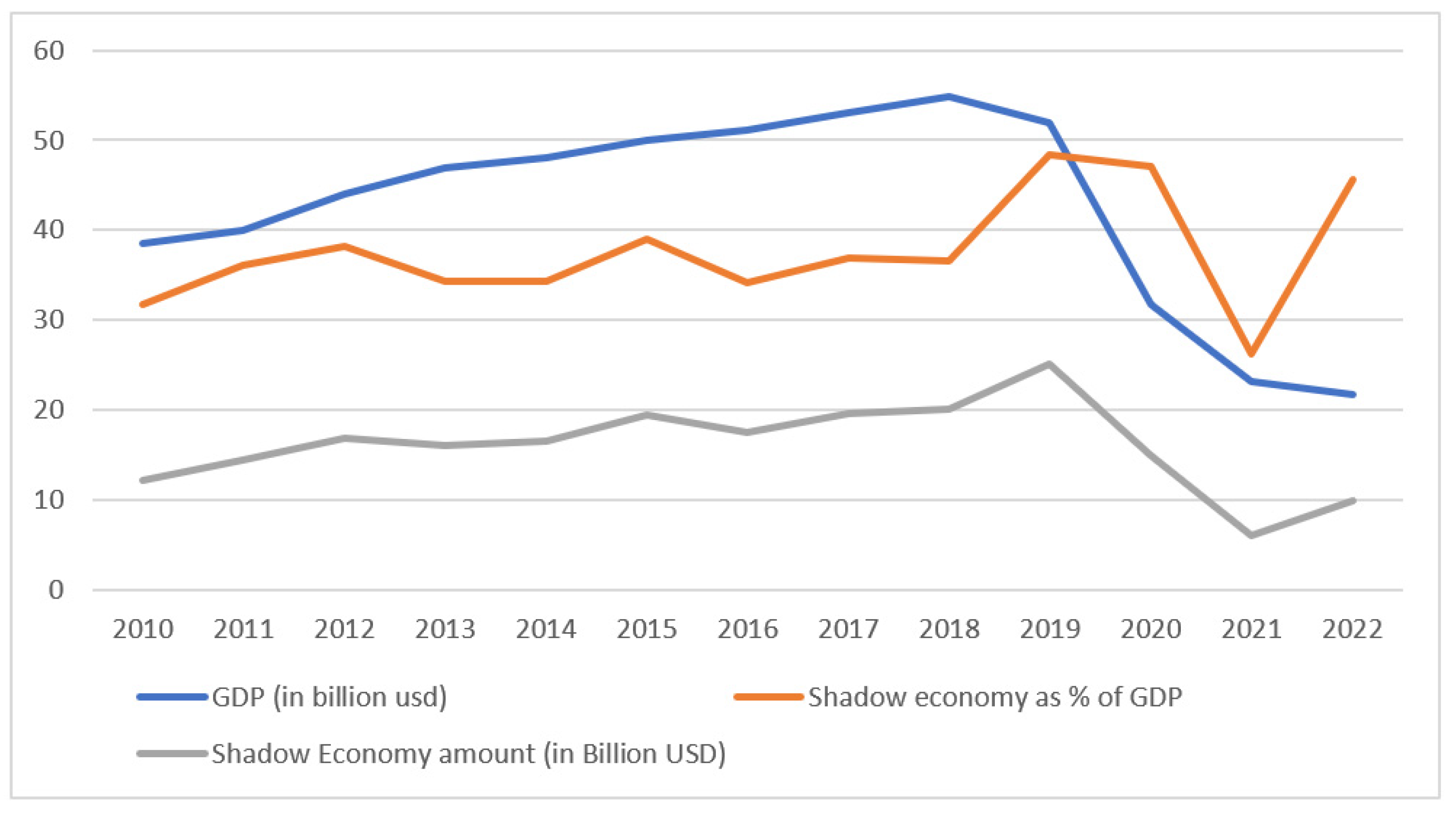

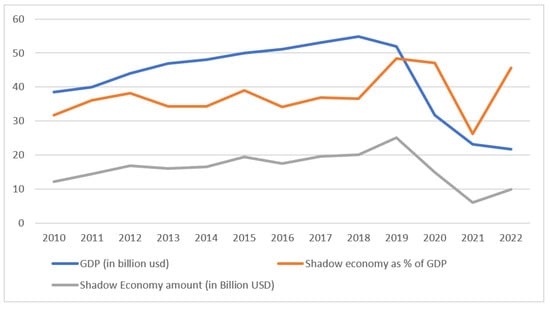

Figure 3, which depicts GDP and shadow economy data from 2010 to 2022, reflects the deep-seated economic challenges facing Lebanon, underscoring the complexity of its ongoing crisis. By 2019, the GDP had fallen, while there was an increase in the shadow economy as a percentage of GDP. This trend resulted from growing economic instability, pushing more activities underground. Since 2019, banking liquidity problems and scarcity of foreign currency have further driven this shift. The economic crisis caused currency depreciation, which intensified the reliance on the shadow economy as formal financial systems struggled and people sought alternative ways to conduct business.

Figure 3.

GDP and shadow economy trends over time (2010–2022), adapted by the authors. Source: Kareh (2020); World Bank (2023).

The consistent rise in the shadow economy as a percentage of GDP reveals the extent to which informal economic activities have proliferated amidst fiscal mismanagement, corruption, and structural vulnerabilities. The data suggest a troubling pattern of economic informality, indicating a lack of trust in formal institutions and regulatory frameworks. The substantial size of the shadow economy underscores the magnitude of tax evasion, regulatory evasion, and informal employment, posing significant challenges to fiscal sustainability, market efficiency, and governance integrity. Moreover, the fluctuation in GDP alongside the shadow economy trends reflects the precariousness of Lebanon’s economic landscape, marked by volatility, uncertainty, and systemic fragility. The COVID-19 pandemic, which started spreading in Lebanon by 2020, exacerbated Lebanon’s economic crisis, leading to a contraction in GDP due to widespread business closures, reduced consumer spending, and increased reliance on the informal sector for survival, further weakening the country’s already fragile financial situation (Bizri et al. 2021).

Given the prevailing political instability and social unrest, the data emphasize the immediate need for robust reform initiatives in Lebanon.

In the subsequent sections of this study, we delve into the role of political patronage networks in exacerbating Lebanon’s economic crisis, examining their influence on economic decision making, financial stability, and governance dynamics. By unpacking the complexities of Lebanon’s economic challenges, we seek to illuminate pathways for reform, resilience, and renewal in the face of adversity.

4. Political Patronage Networks in Lebanon and the Impacts

Lebanon’s political landscape is characterized by a complex mosaic of sectarian affiliations, historical rivalries, and power-sharing arrangements (Brown-Jackson et al. 2019). The country’s confessional system, enshrined in its political institutions, allocates positions of power and influence along sectarian lines, fostering a fragmented and often contentious political environment (Harb 2006). At the center of Lebanon’s political system are entrenched political parties and factions, each vying for dominance and influence within the country’s power structures (Harb 2006).

These political actors, often aligned along sectarian lines, wield significant sway over electoral politics, government appointments, and policy decisions, perpetuating a system of patronage and clientelism.

The intricate web of political patronage networks lies at the heart of Lebanon’s economic crisis, exerting significant influence over decision-making processes, resource allocation, and governance structures (Dibeh n.d.). Understanding the composition, dynamics, and modus operandi of these networks is essential for unraveling the complexities of Lebanon’s economic challenges.

4.1. Role of Political Elites in Economic Decision Making

Political elites, drawn from Lebanon’s entrenched political parties and factions, play a central role in shaping the country’s economic policies and priorities. Through their control of key government ministries, regulatory bodies, and public institutions, political elites exercise considerable influence over economic decision-making processes, resource allocation, and investment strategies.

The intertwining of political and economic interests is pervasive within Lebanon’s political elite, with many political leaders also holding significant financial stakes in various sectors of the economy. This convergence of political and economic power enables political elites to advance their own interests, consolidate their hold on power, and perpetuate systems of patronage and clientelism (Johnston 2005).

4.2. Interconnectedness between Political and Financial Interests

Lebanon’s economic landscape is intricately linked to its political dynamics, with political patronage networks exerting considerable influence over the country’s financial institutions, regulatory frameworks, and business environment. The close nexus between political and financial interests facilitates the manipulation of economic policies, the allocation of financial resources, and the perpetuation of rent-seeking behaviors (Auyero et al. 2009).

Key sectors of the economy, including banking, real estate, and infrastructure development, are often dominated by politically connected individuals and business interests, further blurring the lines between politics and economics. This intertwining of political and financial interests undermines market competition, fosters crony capitalism, and stifles innovation and entrepreneurship (Brown-Jackson et al. 2019).

In the subsequent sections, we delve into specific case studies and analyses that illuminate the mechanisms through which political patronage networks influence Lebanon’s financial stability, governance structures, and reform efforts. By examining concrete examples and manifestations of patronage networks, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of their impact on Lebanon’s economic crisis and to offer insights that inform policy discourse, academic inquiry, and collective action aimed at addressing the root causes of the crisis.

4.3. Case Studies and Insights from Interviews

Examining specific case studies provides valuable insights into the intricate dynamics of political patronage networks and their impact on Lebanon’s economic crisis. Through detailed analysis, we explore the mechanisms through which these networks operate, their consequences for financial stability, and their implications for governance and reform efforts.

- 1.

- Influence of Political Actors on Financial Policies

One prominent manifestation of political patronage networks is the influence exerted by political actors over financial policies and regulatory frameworks. Case studies reveal instances where political elites have manipulated economic policies to serve narrow political interests, prioritize rent-seeking behaviors, and perpetuate systems of patronage and clientelism.

Examples include the allocation of government contracts, subsidies, and investment incentives to politically connected individuals and businesses, often at the expense of broader economic development and public welfare. Political interference in monetary policy, regulatory enforcement, and fiscal management further undermines market confidence, erodes investor trust, and exacerbates systemic vulnerabilities within Lebanon’s financial system.

- 2.

- Role of Patronage Networks in Banking Sector Governance

Lebanon’s banking sector, long regarded as a cornerstone of the country’s economy, has been deeply intertwined with political patronage networks, exacerbating vulnerabilities and systemic risks. Case studies highlight instances where politically connected individuals and entities have leveraged their influence to gain preferential treatment, access to credit, and regulatory leniency within the banking sector.

The ownership structure of most banks in Lebanon reveals a significant presence of politicians, whether they are current or former government officials or their companies hold shares in these banks. Specifically, in 18 out of 20 cases, politicians are linked to bank ownership, while 15 out of 20 banks have politicians serving on their board of directors (Diwan 2019). This indicates a direct association between banks, their owners, management, and the state.

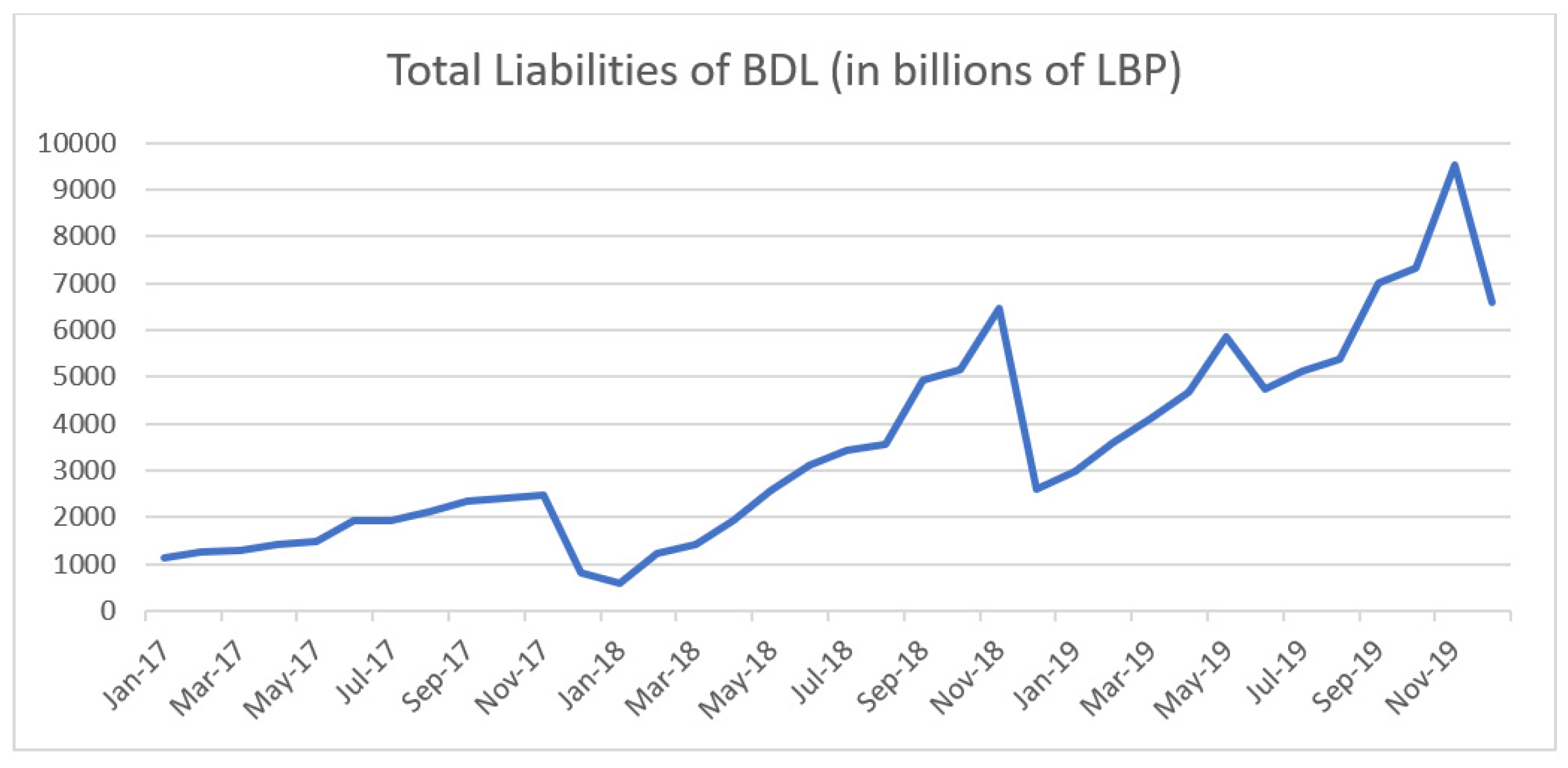

Lebanon’s political and economic elites were deeply involved in government policies that favored the banking sector, which was particularly evident in the imposition of notably high interest rates on government debt securities acquired by Lebanese banks. The period spanning from 1993 to 2019 witnessed significant financial transformations, as public debt surged from USD 4.2 billion to USD 92 billion, representing a remarkable increase of over 2000%, while bank assets surged by more than 1300% to reach USD 248.88 billion, surpassing the modest 370% growth in GDP. Moreover, private banks experienced an astonishing 3000% rise in net profits, escalating from USD 63 million to USD 2 billion between 1993 and 2018. These policies were anchored by the engineered USD–LBP peg in 1997, artificially linking the Lebanese pound and the state’s debt in dollars, resulting in a substantial influx of capital (Abdo et al. 2020).

The financial engineering scheme in Lebanon, as outlined in Table 1, highlights the intricate workings of the banking sector, which often operates within a framework influenced by political patronage networks. The surge in bank assets and liabilities reflects not only financial activities but also the extent to which patronage networks may exert influence over banking sector governance. The disruption and vulnerabilities exposed by the scheme underscore the risks associated with unsustainable financial practices exacerbated by patronage networks, thereby emphasizing the critical role of addressing patronage in ensuring the integrity and stability of banking sector governance in Lebanon.

Table 1.

Analysis of events and roadmap conclusions regarding political patronage in Lebanon’s economic sectors (Ahmad et al. 2022; Simet 2023).

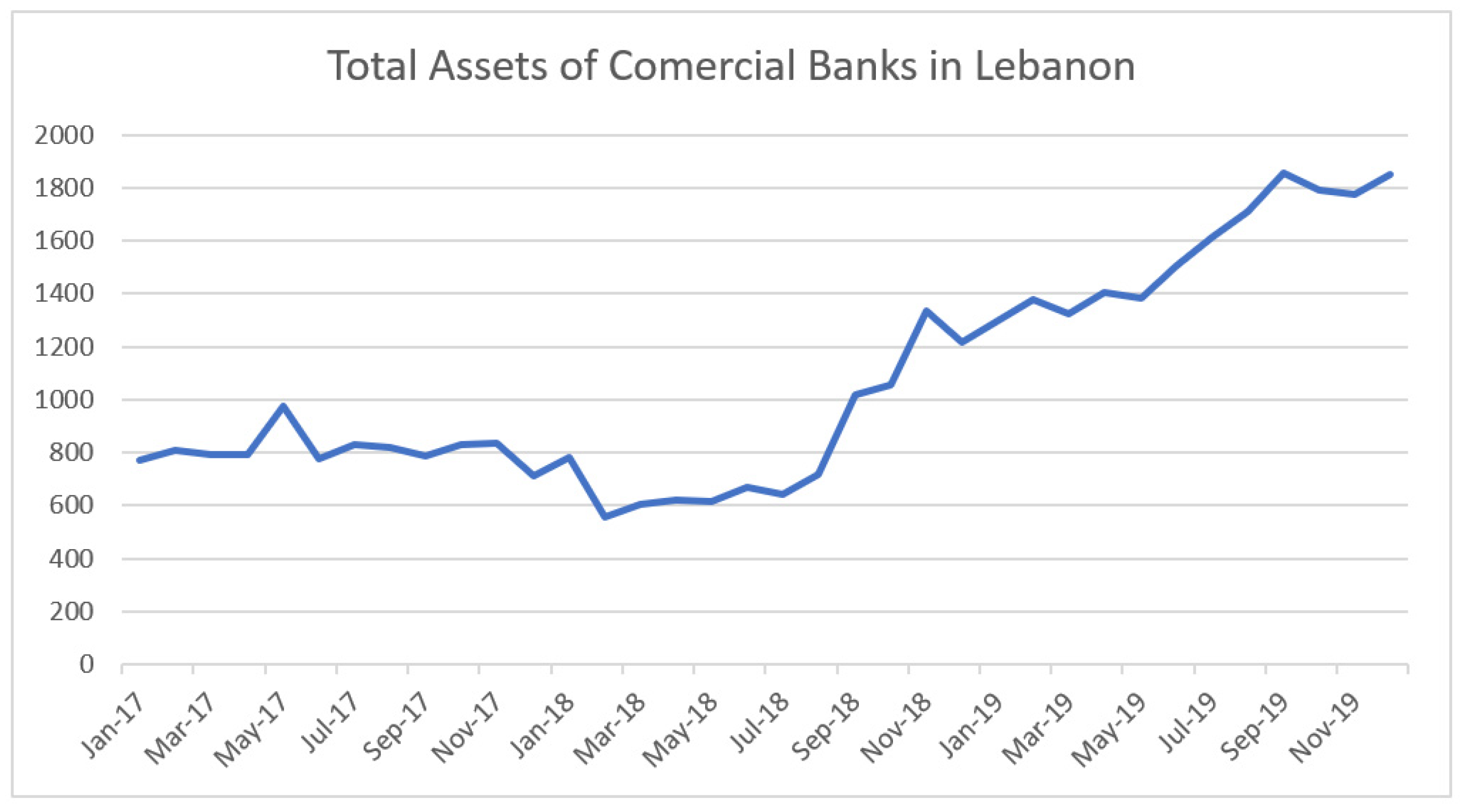

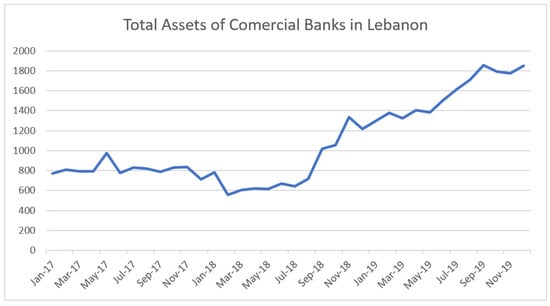

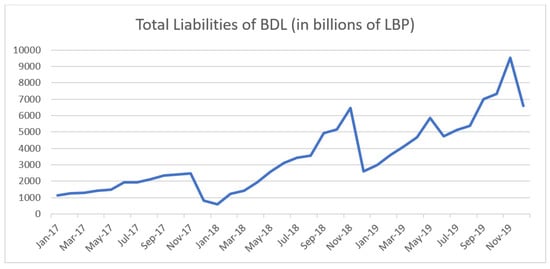

The surge in bank assets and liabilities reflects the extensive financial activities driven by the Ponzi-like financial engineering scheme in Lebanon. This scheme, orchestrated by the Central Bank, involved swaps of sovereign bonds between commercial banks and the government, resulting in a significant increase in bank balance sheets.

In summary, the rise in commercial bank assets (Figure 4) and BDL liabilities (Figure 5) underscores the nexus between political decisions, financial policies, and economic stability in Lebanon. The episode highlights the need for enhanced transparency, accountability, and regulatory oversight within the financial sector to mitigate systemic risks and protect depositor savings and overall economic resilience.

Figure 4.

Total assets of commercial banks from 2017 to 2019, adapted by the authors. Source: BDL (2023a).

Figure 5.

Total liabilities of BDL from 2017 to 2019, adapted by the authors. Source: BDL (2023b).

The concentration of economic power and financial resources within a select group of politically connected banking elites has perpetuated systemic risks and market distortions within Lebanon’s financial landscape. This symbiotic relationship between political and financial interests has hindered the effective allocation of capital, the management of risk, and the promotion of financial inclusion, posing profound challenges to the stability and sustainability of Lebanon’s economy. Addressing these entrenched issues demands comprehensive reforms that prioritize transparency, accountability, and the depoliticization of the banking sector to restore public trust and ensure economic resilience.

- 3.

- Impact of Corruption on Financial Institutions

Governments’ effectiveness and regulatory quality are crucial dimensions of good governance that directly influence corruption. Effective governance institutions with strong enforcement mechanisms and transparent practices can deter corrupt activities. Clear and well-enforced regulations minimize opportunities for corruption by reducing bureaucratic discretion. Given the significant impact of these factors on corruption, our paper focuses on examining corruption and its implications for economic development (Kaufmann et al. 2010).

Corruption, facilitated by political patronage networks, poses a significant threat to the integrity, stability, and credibility of Lebanon’s financial institutions. Case studies reveal instances of embezzlement, bribery, and fraud within banking institutions, facilitated by collusion between political elites, regulatory authorities, and financial intermediaries.

This table provides an analysis of key events related to political patronage in Lebanon’s economic sectors. Each event underscores the detrimental impact of political influence on governance and the need for reforms to ensure transparency, fairness, and accountability. These conclusions form the basis of a roadmap towards sustainable economic development and governance reform in Lebanon’s economic landscape.

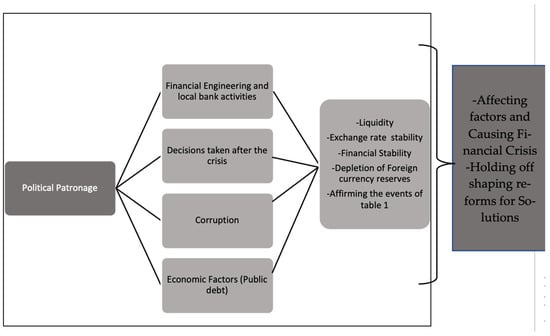

4.4. Insights from Interview Analysis of Lebanon’s Financial Crisis

The outcomes of the interviews reveal a complex web of interdependencies among critical nodes in Lebanon’s financial crisis. At its core, political issues wield a profound influence, not only directly impacting compliance measures and financial engineering strategies but also shaping decision-making processes post-crisis. This nexus between political issues and compliance measures sets the stage for the intricate relationship between financial engineering and local banking activities, both of which significantly impact economic factors. Furthermore, the interviews underscore how political issues directly influence exchange rate fluctuations, further complicating the economic landscape. Ultimately, these findings highlight the pivotal role of these interwoven and interdependent factors in shaping recommendations and future solutions for the myriad challenges facing Lebanon’s financial sector. Refer to Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Insights from interviews regarding factors behind the financial crisis in Lebanon, adapted by the authors.

“BDL was fulfilling the politicians’ requests to cover budget deficit and using depositors’ funds”, revealing the significant impact of politics on banking operations. This interconnectedness also reaches into economic aspects, as highlighted by another specialist: “Banks utilized individuals’ funds in the financial engineering rather than investing elsewhere, like supporting SMEs, while the government was not working to solve its deficit and corruption proceeded”, emphasizing the consequences of political intervention for Lebanon’s economic equilibrium.

5. Methodology

To investigate the intricate interplay between political patronage networks and Lebanon’s economic crisis, a qualitative research approach was adopted. This methodology integrates insights from three economic theories—the Classical Theory of International Trade, the Keynesian Theory of Aggregate Demand, and the Monetary Approach to the Balance of Payments—along with principles of Project Management (PM) to offer a comprehensive analysis. Qualitative methods offer a nuanced understanding of complex phenomena, allowing for in-depth exploration and analysis of contextual dynamics (Maxwell 2012; Myers 2019), like, in our case, the financial–political situation in Lebanon.

5.1. Data Collection Methods

- Literature Review and Document Analysis: A comprehensive review of primary and secondary sources, including government documents, policy reports, media articles, and academic literature, was conducted to contextualize the findings of the study. Document analysis provided valuable insights into historical trends, policy trajectories, and institutional dynamics shaping Lebanon’s economic crisis.

- In-Depth Interviews: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with key stakeholders to elicit insights, perspectives, and firsthand accounts of the functioning of political patronage networks in Lebanon. Interviews were tailored to explore participants’ experiences, observations, and analyses of the intersection between political power dynamics and economic decision making.

- Selection of Participants: In total, 22 individuals were interviewed, as represented in Table 2, based on their expertise, knowledge, and experience relevant to Lebanon’s political and economic landscape. Key informants included policymakers, economists, academics, and individuals with firsthand experience of or insights into the workings of political patronage networks and financial networks, including deputies in Parliament. NVivo facilitated systematic organization and analysis of qualitative data, unveiling patterns and relationships within the dataset.

Table 2. Number and groups of interview participants, by the authors.

Table 2. Number and groups of interview participants, by the authors.

- Case Studies: In-depth case studies were employed to examine specific instances of political patronage networks within Lebanon’s economic landscape, shedding light on their mechanisms and consequences.

Event Analysis: A critical analysis of key events related to political patronage networks and their impact on Lebanon’s economic crisis was conducted. The events were analyzed to draw conclusions regarding the role of political patronage networks in exacerbating the crisis and hindering governance reforms.

5.2. Integrating Insights: Synthesizing Findings

The study’s strength lies in its combination of diverse qualitative research methods. A comprehensive review of government documents and academic literature provided insights into Lebanon’s economic crisis. Semi-structured interviews with policymakers, economists, academics, and individuals with firsthand experience offered diverse perspectives on political patronage networks. In-depth case studies examined specific instances, shedding light on their mechanisms and consequences. This approach facilitated a robust exploration of the intersection between political power dynamics and economic decision making in Lebanon, informing policy discourse and academic inquiry.

6. Analysis: Economic Challenges and Implications

Lebanon’s economic quagmire is emblematic of a complex interplay of political patronage networks, crony capitalism, and institutional deficiencies, posing profound challenges to its stability and prosperity. This critical analysis dissects the intricate web of factors contributing to Lebanon’s economic malaise, highlighting systemic weaknesses and offering insights for transformative reform.

6.1. Governance Paralysis in the Shadow of Crony Capitalism

The pervasive influence of crony capitalism has entrenched Lebanon’s governance structures in a quagmire of corruption, nepotism, and inefficiency. Political elites, entrenched in patronage networks, wield disproportionate power, subverting democratic principles and perpetuating a culture of impunity. State institutions, compromised by political interference and regulatory capture, fail to uphold the rule of law and safeguard public interests. The result is governance paralysis that undermines trust, stifles innovation, and perpetuates socio-economic disparities.

6.2. Financial Fragility: Navigating the Nexus of Political and Financial Interests

Lebanon’s financial sector, marred by political interference and regulatory loopholes, stands on shaky ground. The fusion of political and financial interests breeds systemic vulnerabilities, exposing the economy to volatility and contagion risks. Investor confidence wanes as transparency dwindles, eroding trust in financial institutions and deterring vital capital inflows. The absence of robust governance mechanisms exacerbates fragility, leaving Lebanon’s financial landscape susceptible to external shocks and internal decay.

6.3. Obstacles to Reform and Accountability Mechanisms

Efforts to catalyze reform face formidable obstacles rooted in entrenched interests and institutional inertia. Political elites, entrenched beneficiaries of the status quo, resist change that threatens their stranglehold on power and privilege. The absence of effective checks and balances perpetuates a cycle of corruption, hindering accountability and impeding progress. Despite calls for transparency and accountability, meaningful reform remains elusive, perpetuating Lebanon’s descent into economic turmoil.

In the context of our study, which primarily focuses on political patronage, the application of economic theories, such as the Keynesian Theory of Aggregate Demand and the Monetary Approach to the Balance of Payments, offers valuable insights into Lebanon’s economic challenges. The Keynesian Theory provides understanding of the fluctuations of domestic consumption and investment concerning foreign demand, illuminating potential barriers to economic reform. Likewise, the Monetary Approach underscores the role of exchange rates and monetary policies in shaping Lebanon’s balance of payments, shedding light on the complexities of external financing and trade balance dynamics. Integrating these economic theories into our analysis allows us to explore the intricate interplay between economic policies, institutional reforms, and accountability mechanisms within the context of political patronage. This nuanced perspective enriches our understanding of Lebanon’s journey towards sustainable development and governance reform, particularly within the realm of political patronage networks and their impact on economic dynamics.

In conclusion, Lebanon’s economic quagmire demands a bold reckoning with entrenched power dynamics, crony capitalism, and institutional malaise. Meaningful reform hinges on confronting vested interests, strengthening governance mechanisms, and fostering a culture of transparency and accountability. It is only through unified and decisive action that Lebanon can forge a trajectory towards economic rejuvenation and inclusive prosperity.

7. Recommendations and Conclusions

7.1. Conclusions

Lebanon’s economic crisis is a deeply entrenched phenomenon rooted in systemic governance failures, political dysfunction, and economic mismanagement. The pervasive influence of political patronage networks, compounded by the insidious grip of crony capitalism, has exacerbated these challenges, perpetuating a cycle of corruption, cronyism, and institutional decay.

This study’s theoretical model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the interrelationships between governance, corruption, political patronage, and economic development. By anchoring our analysis in New Institutional Economics (NIE) and relevant economic theories, we have delineated the intricate connections among these key indicators. This theoretical underpinning forms the basis for our empirical investigations, guiding our exploration of the complex dynamics shaping Lebanon’s governance landscape and economic trajectory.

However, amid the daunting challenges lies an opportunity for renewal, reform, and revitalization. Economic theories, such as the Keynesian Theory of Aggregate Demand and the Monetary Approach to the Balance of Payments, shed light on the causes of the crisis. Additionally, integrating NIE and Project Management (PM) principles offers a pathway for recovery and reform. NIE provides insights into how institutions shape economic behavior, emphasizing incentives, transaction costs, and property rights. PM, on the other hand, offers structured planning and execution tools, ensuring clear goals, resource efficiency, and risk management.

By leveraging NIE and PM frameworks, Lebanon can navigate the complexities of governance reform, address institutional deficiencies, and foster sustainable economic development. The recommendations outlined in this paper represent a starting point for action, a roadmap for reform, and a call to arms for all those committed to building a brighter future for Lebanon. It is incumbent upon policymakers, civil society leaders, business stakeholders, and citizens alike to seize this moment, demand accountability, and work tirelessly towards a Lebanon that is prosperous, just, and inclusive for all.

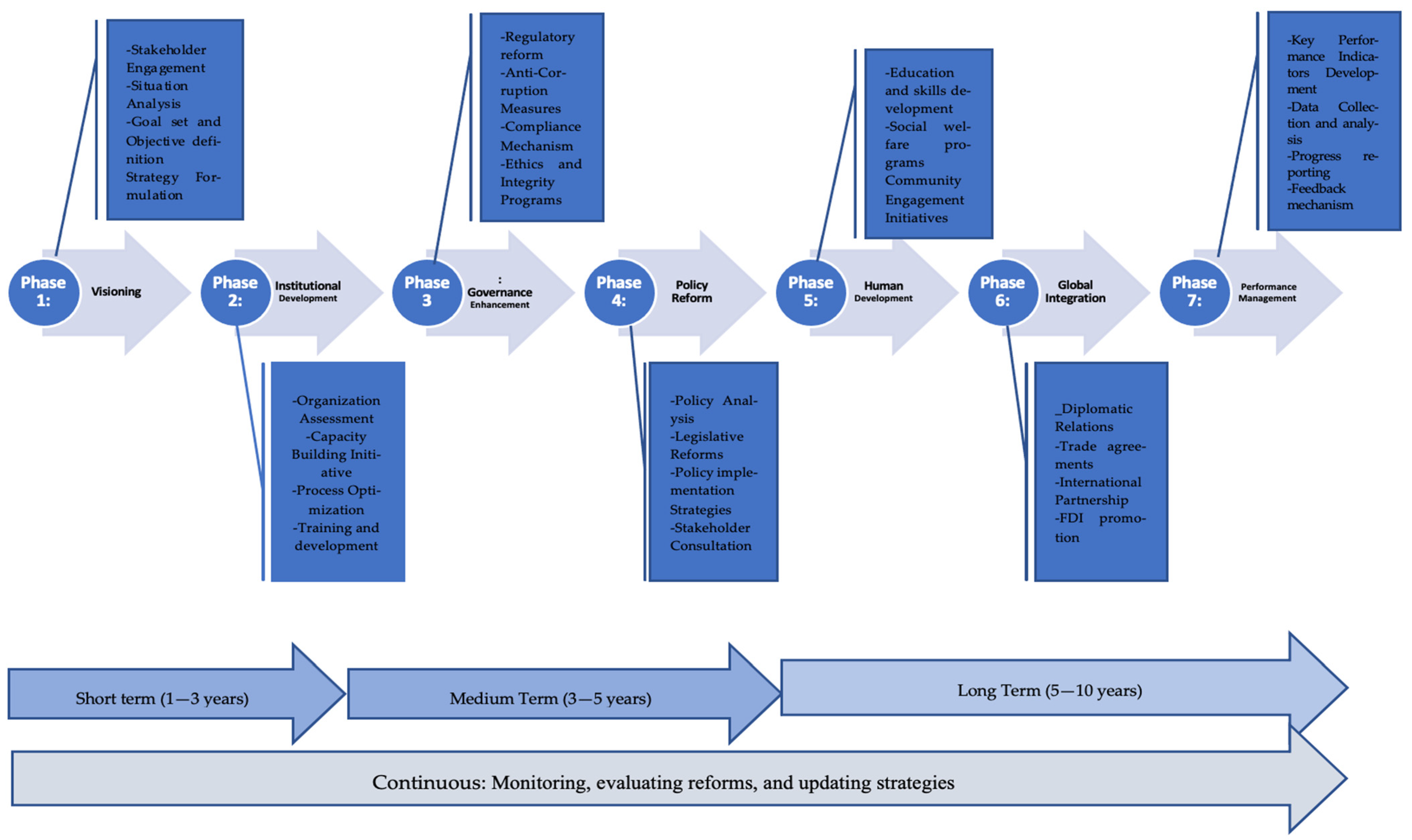

7.2. Recommendations

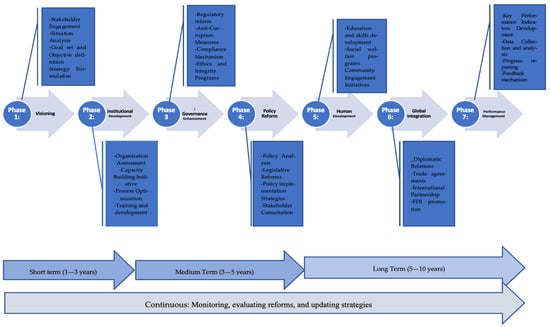

Figure 7 illustrates a comprehensive framework for combating political patronage, corruption, and crony capitalism by integrating New Institutional Economics (NIE) principles with Project Management methodologies. At the core of the framework are seven interconnected phases: Strategic Vision and Planning, Institutional Strengthening and Capacity Building, Transparency and Accountability, Policy Innovation and Adaptability, Investment in Human Capital and Social Development, Regional and International Engagement, and Monitoring and Evaluation. Each phase addresses specific aspects of governance reform and economic development, leveraging NIE insights to analyze institutional contexts and employing Project Management practices to design and implement effective interventions. By integrating efforts across these phases, countries can develop holistic strategies to combat corruption, enhance transparency, and promote inclusive growth, fostering sustainable development and governance outcomes.

Figure 7.

Integrated governance reform framework, by the authors.

Details Concerning Roadmap for Governance Reforms in Lebanon

In the short term, the focus will be on vision-setting and institutional development. The first year involves developing a national vision for reform through inclusive consultations with political leaders, civil society, and international partners, led by the Presidential office and the Ministry of Planning. Over the next two years, efforts will shift to establishing independent institutions, like an anti-corruption commission, and strengthening the electoral commission’s independence, along with judicial reforms to ensure impartiality. Challenges will include resistance from political elites and limited resources.

The medium term will concentrate on governance enhancement and policy reform. This involves enhancing transparency and accountability by implementing protocols for public officials and stricter regulation of campaign financing, led by the anti-corruption commission and the Ministry of Interior. Empowering local governments with financial and decision-making autonomy will also be crucial, requiring legislative support and local coordination. Promoting inclusive political systems through proportional representation and encouraging non-sectarian political parties, alongside economic diversification policies, will be led by the Lebanese Parliament and international democratic support organizations. Obstacles will include political interference and entrenched sectarian loyalties.

In the long term, efforts will focus on human development, global integration, and performance management. Investing in education and healthcare to build human capital will be a priority, led by the Ministries of Education and Health. Programs to empower youth and women will be managed by the Ministries of Youth and Sports and Women’s Affairs. Strengthening international partnerships and adopting global best practices in governance will be overseen by the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Economy. Finally, establishing a performance management system to monitor and evaluate reforms will ensure continuous improvement, led by the Ministry of Planning and independent auditors. Potential obstacles include budget constraints, cultural barriers, and resistance to accountability.

The roadmap for governance reforms in Lebanon includes continuous processes, particularly in the long-term phase of performance management and ongoing improvement. Monitoring, evaluating reforms, and updating strategies based on performance data are continuous efforts crucial for the sustainability and success of the reforms. Considering the context of entrenched political interests, Table 3 includes specific policy measures and practical steps that could be adopted to mitigate the influence of patronage networks.

Table 3.

Specific policy measures and practical steps to mitigate the influence of patronage networks, adapted by the authors.

This study acknowledges some limitations. The methods used for data collection, interviews, may be subject to biases, like self-reporting bias, recall bias, or interviewer bias, which may affect the reliability of the data. To mitigate these issues, some methods were implemented, including standardized interview procedures, choices of interviewers, and triangulation with multiple data sources.

Future research directions are being considered based on the findings of this paper and to further address its limitations. These include evaluating the effectiveness of the implemented governance reforms and comparing Lebanon’s crisis with those of other politically fragile economies to understand different approaches and outcomes. Additionally, exploring international cooperation in combating corruption and assessing the applicability of successful anti-corruption measures undertaken by other countries to Lebanon are areas of active investigation. Conducting quantitative research to identify socio-economic factors with the highest impact on financial situation and GDP is also underway. Longitudinal analyses to track institutional decisions (before and after the crisis), as well as changes over time, will offer a deeper understanding of the efficacy and sustainability of reforms. These efforts aim to provide a comprehensive and robust agenda for future studies, contributing to the development of effective policy solutions for Lebanon.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, visualization, project administration, review and editing, and funding acquisition: S.A.L. Supervision and review: S.M.-Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted without external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdo, Nabil, Abed Dana, Ayoub Bachir, and Nizar Aouad. 2020. The IMF and Lebanon: The Long Road Ahead—An Assessment of How Lebanon’s Economy May Be Stabilized While Battling a Triple Crisis and Recovering from a Deadly Blast. Oxfam. Oxford: Oxfam GB. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouzeid, Rania. 2021. How Corruption Ruined Lebanon. The New York Times, October 28. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, Daron, and Thierry Verdier. 2000. The Choice between Market Failures and Corruption. American Economic Review 90: 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. 2001. The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation. American Economic Review 91: 1369–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Ali, Neil McCulloch, Muzna Al-Masri, and Marc Ayoub. 2022. From dysfunctional to functional corruption: The politics of decentralized electricity provision in Lebanon. Energy Research & Social Science 86: 102399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison McCulloch. 2022. ‘Revisiting the Politics of Sectarianism Amidst Lebanon’s Concomitant Crises’. Roundtable Summary Booklet. Paris: Sciences Po. [Google Scholar]

- Auyero, Javier, Pablo Lapegna, and Fernanda Page Poma. 2009. Patronage Politics and Contentious Collective Action: A Recursive Relationship. Latin American Politics and Society 51: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azfar, Omar. 2002. The NIE Approach to Economic Development. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development. [Google Scholar]

- BDL. 2023a. Available online: https://www.bdl.gov.lb/statisticsandresearch.php (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- BDL. 2023b. Banque Du Liban. Available online: https://www.bdl.gov.lb/economicandfinancialdatasub.php?docId=17&code=1&filecode=100 (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Bitar, Joseph. 2021. The Monetary Crisis of Lebanon. Review of Middle East Economics & Finance 17: 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bizri, Abdul Rahman, Hussein H. Khachfe, Mohamad Y. Fares, and Umayya Musharrafieh. 2021. COVID-19 Pandemic: An Insult Over Injury for Lebanon. Journal of Community Health 46: 487–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, Derick, and Arthur Goldsmith. 2002. Clientelism, Patrimonialism and Democratic Governance: An Overview and Framework for Assessment and Programming. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development Office of Democracy and Governance under Strategic Policy and Institutional Reform. [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Jackson, Maia, Sarah Gold, and Isais Medinas. 2019. Lebanon-Understanding the Regime. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372482947_Lebanon-_Understanding_the_Regime (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Chletsos, Michael, and Andreas Sintos. 2024. Political stability and financial development: An empirical investigation. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 94: 252–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, Ramesh Chandra, and Jagabandhu Mandal. 2022. Long-Run Associations and Short-Run Dynamics Between Corruption and Inflation: Examining Social Unsustainability for the Panel of Countries. International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development (IJSESD) 13: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, Ramesh, and Utpal Das. 2014. Interrelationships among Growth, Confidence and Governance in the Globalized World-An experiment of some selected countries. International Journal of Finance & Banking Studies (2147-4486) 3: 68–83. Available online: https://www.ssbfnet.com/ojs/index.php/ijfbs/article/view/387 (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Dibeh, Dr Ghassan. n.d. The Financial Recovery Plan: Its Impact on Lebanon’s Economic Model, Negotiations with the IMF, and Recession. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Available online: https://lebanon.fes.de/user_upload/documents (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Diwan, Ishac. 2019. Crony Capitalism in the Middle East: Business and Politics from Liberalization to the Arab Spring. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, Avinash. 2002. Some Lessons from Transaction-Cost Politics for Less-Developed Countries. Economics and Politics 15: 107–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Husseini, Rola, and Ryan Crocker. 2012. Pax Syriana: Elite Politics in Postwar Lebanon. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fahed-Sreih, Josiane. 2023. Corruption and New Insights in Lebanon. In Corruption—New Insights. London: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, John. 2013. Evolutionary Macroeconomics (Routledge Revivals). London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gebeily, Maya. 2024. Lebanon’s Parliament Passes 2024 Budget, Shunning Major Reforms. Reuters, January 27. [Google Scholar]

- Girma, Sourafel, and Anja Shortland. 2008. The political economy of financial development. Oxford Economic Papers 60: 567–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb. 2006. Lebanon’s Confessionalism: Problems and Prospects. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace. Available online: https://www.usip.org/publications/2006/03/lebanons-confessionalism-problems-and-prospects (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Hourani, Albert. 1991. A History of the Arab Peoples. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Available online: https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674058194 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- IMF. 2020. Lebanon IMF Executive Board Concludes 2019 Article IV Consultation. New Hampshire: IMF. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2019/10/17/pr19378-lebanon-imf-executive-board-concludes-2019-article-iv-consultation-with-lebanon (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Jargad, Shruti. 2022. Book Review: Yuen Yuen Ang, China’s Gilded Age: The Paradox of Economic Boom and Vast Corruption—Shruti Jargad. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/00094455221074289 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Johnson, Michael. 1986. Class & Client in Beirut: The Sunni Muslim Community and the Lebanese State, 1840–1985. Ithaca: Ithaca Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Michael. 2005. Syndromes of Corruption: Wealth, Power, and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kareh, Marie Dahdah. 2020. The Reform of the Tax System in Lebanon: An Impossible Equation? Doctoral thesis, Université Panthéon-Sorbonne-Paris I, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2010. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues. SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester: SSRN, September 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, Paul W. T. 2013. Reproducing Sectarianism Advocacy Networks and the Politics of Civil Society in Postwar Lebanon. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luciani, Giacomo. 1990. The Arab State. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Makdisi, Ussama. 2000. The Culture of Sectarianism by Ussama Makdisi—Paperback—University of California Press. Available online: https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520218468/the-culture-of-sectarianism (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Mauro, Paolo. 1995. Corruption and Growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 110: 681–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, Joseph A. 2012. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- MayBaaklini. 2023. The Absent Leviathan the Fate of Power Sharing in Lebanon. Beirut: American University of Beirut. Available online: https://scholarworks.aub.edu.lb/bitstream/handle/10938/24163/MayBaaklini_2023.pdf?sequence=7 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Murad, S. M. Woahid. 2022. The role of domestic and foreign economic uncertainties in determining the foreign exchange rates: An extended monetary approach. Journal of Economics and Finance 46: 666–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Michael D. 2019. Qualitative Research in Business and Management. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- National Debt by Country. 2019. The Top IOU Nations. SpendMeNot, December 4. Available online: https://spendmenot.com/blog/national-debt-by-country/ (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Natsvaladze, Marina. 2023. The New Institutional Economics and Digitalization. In Digital Management to Shape the Future, Proceedings of the 3rd International Scientific Practical Conference (ISPC 2023), Lviv, Ukraine, 9–10 November 2023. Georgia: East European University. [Google Scholar]

- North, Douglass C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, Tarek. 2013. Egypt on the brink: From Nasser to the Muslim Brotherhood. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 1–309. [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua, Victoria, and Jan P. Vogler. 2022. Economic elites and the constitutional design of sharing political power. Constitutional Political Economy 33: 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMBOK Guide. 2021. Project Management Institute. Available online: https://www.pmi.org/pmbok-guide-standards/foundational/pmbok (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Quisumbing, Agnes R., and Lauren Pandolfelli. 2010. Promising Approaches to Address the Needs of Poor Female Farmers: Resources, Constraints, and Interventions. World Development 38: 581–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Ackerman, Susan. 1999. Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences, and Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salamey, Imad. 2013. The Government and Politics of Lebanon. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simet, Lena. 2023. Cut Off From Life Itself. New York: Human Rights Watch. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, Alessandra, and Tamirace Fakhoury. 2022. Power-Sharing System entrenches Recurring Dilemmas that undermine Reform and Citizen Well-Being. Available online: https://bibnum.sciencespo.fr/files/original/5614b851b61f84159bb25d62b12f9cafd81c975d.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Towett, Geofrey, and John Ndungu Kungu. 2020. The Implication of Political Patron-Client Linkages on Democratic Governance in Developing Democracies. International Journal of Innovative Research and Advanced Studies (IJIRAS) 7: 2394–4404. [Google Scholar]

- Treisman, Daniel. 2000. The causes of corruption: A cross-national study. Journal of Public Economics 76: 399–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2021. Lebanon Sinking into One of the Most Severe Global Crises Episodes, Amidst Deliberate Inaction. Washington: World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/05/01/lebanon-sinking-into-one-of-the-most-severe-global-crises-episodes (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- World Bank. 2023. Lebanon: Normalization of Crisis Is No Road to Stabilization. Washington: World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/05/16/lebanon-normalization-of-crisis-is-no-road-to-stabilization (accessed on 13 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).