3. Methodology

For a theory to contribute to scientific knowledge, Patterson [

36] proposed eight criteria. As stated earlier in the introduction, the blending of traditional and holistic education was proposed as an answer to today’s educational problems. The research question of this review blends a holistic educational paradigm such as Waldorf schools with aspects of MI theory and neuroeducation. Such a suggestion has relevance to actual life since it may explain why Waldorf students have certain attributes. It has a practical value as well, since it could lead to a new curriculum proposal, blending traditional and alternative school’s curricula. The choice of conducting a systematic literature review was made because the systematic aspect of the review could act as a foundation to a future empirical research. The results of this systematic review can be the basis of an empirical study that will test the proposed relationship.

This literature review follows the guidelines described in the PRISMA statement [

37], as well as those proposed by Petticrew & Roberts [

38]. A list of inclusion criteria was made in order to collect the necessary articles. The intention was to find the greatest number of empirical studies about Waldorf education and, from there on, to distinguish which studies could be linked to MI theory and which to neuroscience in order to answer RQ1 and RQ2. The eligibility criteria are shown in

Table 1.

Appendix A contains more information about the methodology. The search included five main academic databases (ERIC, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, and Scopus) websites and journals related to Waldorf education (Research on Steiner Education (Rose), The Online Waldorf Library, see

Appendix A Table A2 for more). Additionally, the publications reference lists added several articles. The search terms used were chosen to return a broad selection of articles about Waldorf education (“(Rudolf AND Steiner) OR (Steiner AND Education) OR Waldorf”).

The PRISMA diagram, shown in

Figure 2, displays the number of publications on each stage. During the screening stage, the title and abstract were screened in order to exclude irrelevant articles. During the eligibility stage, the inclusion criteria were applied to the full text. The screening and eligibility phases were conducted by a single researcher while the second researcher participated by examining a sample of them.

This procedure led to the creation of a database of 43 scientific papers to be reviewed fulfilling the criteria set and corresponding to RQ1 as well as of 10 papers corresponding to RQ2. There were six papers that were relevant to both RQ1 and RQ2.

For the collection of the data, a form was used that was pilot-tested on the first included articles from the ERIC database. Both researchers participated independently in the data extraction process and in the case of different views, a consensus was needed.

A coding system was created to associate, in a qualitative manner, each publication to the research questions. The articles were searched for methods that connected the way children are taught in Waldorf schools and the way children could be taught according to the MI theory [

23,

39]. Armstrong [

8] describes ways and methods to integrate MI theory with teaching (

Table 2).

To this end, a two-way method was followed. Firstly, an examination of the publications from the MI theory end to the Waldorf end was made. A list with teaching strategies that are well-suited to MI theory was created and the articles were searched for evidence that these strategies are used in Waldorf schools (

Figure 3).

For each teaching strategy that taps into a specific intelligence, a code was associated. A similar approach was taken with the focus or concept of each study. Each study had a different focus, which was depended on the goal of the study. All the relevant articles were associated with one concept. The concepts were the MI theory eight “intelligences” and the neuroeducation concept. For example, in Rose, Jolley, and Charman [

40], the goal was to examine the Expressive and Representational Drawings in different school settings. The study focus “drawing development” can be related to the MI’s

spatial intelligence. As such it was identified as “spatial” and was tagged with the

spatial concept (

Table 3.). After reading the study and specifically its results, it was associated with three codes, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic and “other.” That meant that the study succeeded in proving its aim and also reported two other results. According to Webster and Watson [

41], the use of such a table, which relates the articles with the key concepts of a topic, is crucial to the transition to a concept-centric review. The table, in this case, lists all the relevant articles, their focus-concepts, the intelligence and neuroeducation codes associated with them, and their type and methodology. The last two fields were included in order to help us critically analyze each article. For the critical analysis, each study was given a quality value starting from evidence resulting from meta-analysis (highest value) and resulting to evidence based on opinions of specialists (lowest value) (for more information see

Appendix A Table A6).

Secondly, the articles were examined for measurable results that derive from the pedagogical methods used in Waldorf schools. In many studies, Waldorf students showed having a positive or negative effect in an area associated to a specific intelligence. Consequently, the appropriate codes were associated to these passages. Finally, a code for neuroeducation was associated whenever article outcomes that exhibited a relation between Waldorf pedagogy and neuroeducation were encountered.

4. Analysis of Results

Table 4 presents each study and the intelligence codes associated to them. The studies that showed a relation of Waldorf education to Neuroeducation are also presented. There were studies that reported a negative correlation of Waldorf schools with some intelligences, which is represented with the minus symbol. Two of the studies, although relevant to the research questions, were neutral and were not given any code.

Nearly half of the studies were comparative studies comparing Waldorf schools to other school types, mostly mainstream. This is a known feature with studies about Waldorf schools, as the most of them are comparative studies [

52]. In these comparative studies, the assessment of Waldorf students in a specific area was usually compared to the assessment of students of mainstream schools. Regarding the field of the study, most of them were about primary-secondary education and about psychology.

Table 5 describes the types of the studies.

Figure 4 shows the number of studies associated with an intelligence code as well as the number of studies about Steiner pedagogy associated with neuroeducation. Studies that were associated with an intelligence not included in Gardner’s list of eight, such as spiritual, were linked to the code “other.”

Each study was given an MI theory intelligence code either by matching similar teaching practices or by examining the results of the study, such as superior performance of Waldorf students to other in an area, e.g., mathematics.

A qualitative analysis follows, where the majority of the studies are discussed as well as their relationship to each intelligence.

4.1. RQ1. How Are Waldorf-Steiner Educational Practices Related to MI theory?

4.1.1. Linguistic

Teaching Methods: Lectures, Discussions, Word Games, Storytelling, Choral Reading, Journal Writing

Cunningham and Carroll [

49] wrote about the way children are taught phonics in Steiner schools. This is described as an analytic approach, including games and the position of letters in familiar words. It was concluded that Steiner students exhibit superior reading-related skills and greater maturity. Nicholson [

68] writes that discussion and a sort of “Socratic” dialogue is a part of the oral tradition of Steiner schools. He also adds storytelling and reciting to that list. Students usually write their own textbooks based on the oral and written feedback given by teachers [

82]. Ashley [

17] states that Waldorf teachers are effective storytellers who operate with a much stronger tradition than teachers in mainstream schools, with recitation and choral speaking being regular features in the curriculum. A known criticism of Steiner schools is the delay in starting to read and write until the age of seven. Suggate [

83] states that students in Steiner schools catch up very quickly with their mainstream counterparts, with no need of intensive instruction. This is attributed to the strong oral language activities in Steiner schools.

4.1.2. Logical-Mathematical

Teaching Methods: Brainteasers, Problem Solving, Science Experiments, Mental Calculation, Number Games, Critical Thinking

Oberman [

69] and Larrison and Dalya [

65] describe studies that show that Waldorf students have equivalent test results in Math tests with students of traditional schools, albeit not in early grades. Randoll and Peters [

70] report a PISA study result that suggests a better understanding of physics among Austrian Waldorf students. Jelinek and Sun [

61], in a study about science education and Waldorf students, describe their deductive ability as on par, if not better, with public schools’ students. In the same study, Waldorf students’ reasoning-skills are labeled as high and their logical reasoning as sophisticated. Waldorf schools are also reported to encourage the use of experiments, the development of problem-solving skills and scientific reasoning. On the other hand, the authors conclude that some pseudoscientific notions, which derive from Steiner’s philosophy, are in contrast with modern mainstream scientific thinking.

4.1.4. Bodily-Kinesthetic

Teaching Methods: Hands-On Learning, Drama, Dance, Sports That Teach, Tactile Activities, Relaxation Exercises

Kanitz et al. [

21] reported on the benefits of Eurythmy in stress and fatigue coping, although in adults. As with other aspects of Waldorf pedagogy, the kinesthetic approach is an integral part of the curriculum, like children forming the number eight in an eurythmy lesson, weaving to calm and gain a sense of balance [

17], or role-playing the trial of Galileo [

85]. Drama plays at the end of the year is considered a method of expression and forming bonds as are dancing and sport events [

80].

4.1.5. Musical

Teaching Methods: Rhythmic Learnings, Using Songs That Teach

Music lessons, singing, and playing instruments are part of the Waldorf special classes and activities [

57,

80]. Singing and reciting is also part of the “main” lesson block with students singing songs related to the lesson or songs with a moral dimension. Of special interest to the changing of the learning rhythm is the singing and reciting breaks that occur between lessons [

68]. Rhythm and musicality are aspects that are carried in language. Steiner associated them with writing using a correct orthography. Because of that, Waldorf teachers must be very articulate in speaking [

82].

4.1.7. Intrapersonal

Teaching Methods: Individualized Instruction, Independent Study, Private Time, Self-Esteem Building

Friedlaender et al. [

57] and Zhang [

81] report about the individualized instruction given to Waldorf students based on a holistic approach. Sobo [

20] discusses the building of “will” in Waldorf kindergartens, which corresponds partly with the results in [

75] that show higher academic self-image. The individualized approach is partially based on the Steiner adherence to the classical though outmoded (for some researchers) idea of “temperaments.” Dahlin [

82] ascertains, though, that this idea should not be scorned since it is implicit in the EAS theory of temperament [

87].

4.1.8. Naturalist

Teaching Methods: Nature Study, Ecological Awareness, Care of Animals

Wright [

84], talking about the geography curriculum in Waldorf schools, states that it moves away from determinism to different cultures and their relationship to nature. Woods et al. [

80], in their study about Steiner school in England, report the well-known fact of using props and resources (like toys, pencil cases, craft material) that are natural. Plastic is excluded from the Waldorf school.

“Gardening… environmental studies and ecology … woodland work, landscape, building paths etc., propagation techniques, caring for bushes/trees, and grafting” form a distinct curriculum area, as the same study informs. Student field trips to farms where the students participate and help care for farm animals are also reported [

57]. Dahlin [

82] writes of a domination of an ecological holistic perspective that explores how everything is connected to the world around it. Rawson and Richter [

88] argue that the Waldorf curriculum, with its connection to nature, preceded today’s interest and concerns about ecology and sustainable development.

4.1.9. Imaginative- Spiritual

One of the prominent features of Waldorf education is its unique imaginative and spiritual character. On the special imaginative quality of Waldorf students, Gidley [

59] reports that they produce rich and positive imaginative visions of the world. This quality is cultivated by the teaching methods of drama, exploration, storytelling, routine, arts, discussion, and empathy [

89]. Furthermore, the imagination playing and the lack of outside influences like plastic toys, cartoons, etc. force the children to use their imagination [

78].

The existential-spiritual intelligence was eventually not included in Gardner’s list of intelligences, but Waldorf schools have a distinct relation with spiritual education. Pearce [

90] studied the spiritual education in Steiner schools and concluded that they are “weakly” confessional schools. They intentionally prepare pupils for spirituality without enforcing a dogma, but they tend to tip the scaled against agnosticism or atheism.

4.2. RQ2. Which Aspects Of Neuroeducation Are Shown To Be Related With Waldorf-Steiner Educational Practices?

Table 6 lists the ten (10) studies associated with the neuroeducation code. Two of these studies [

58,

77] were not specifically about education but associated certain aspects of Steiner pedagogy to neuroeducation. Six studies were also relevant to RQ1. Τhe number of articles related to RQ2 is small. Only five articles had a neuroeducation focus.

The 10 studies describe Waldorf school practices that were quantitively associated to characteristics crucial to cognitive development. Neuroeducation focuses on some educational topics: the linguistic and mathematical skills and problems, the social and emotional “intelligence,” and the attention levels of students. A critical factor is also the cognitive development of the children related to age, something that is central to Steiner’s pedagogy, with his age stages. Educational aspects that associate to these topics and were present to the articles were given the neuroeducation code.

A discussion of these associations follows.

4.2.1. Late Entry

Waldorf students start primary schooling at the age of seven, following Steiner’s development stages. Under this tradition, children start learning to read and write in a later age that it is usually practiced in mainstream schools. Puhani and Weber [

91], in their study in the German school system, report positive effects for entering school at a higher age. It is supported [

3,

82] that when stimulation is presented at an inauspicious time, this may harm the ideal growth of neural connections and that any effort spent on formal teaching in early age may harm creativity and the students’ cognitive development. According to Suggate [

83], there is a list of skills that are crucial to have in order to start formal schooling, namely, neural maturation, language, attention, social skills, memory, and general knowledge. Suggate [

83] also calls for further research about potential psychological or developmental costs to early literacy instruction.

4.2.2. ADHD

Halperin and Healey [

92] reported that physical exercise and play impact the development of the human high-order executive functions. In the same review, it is supported that directed play, physical exercise, and the engagement of children in sports and nature could benefit children with ADHD in a more persistent manner than drugs and behavioral intervention. A study by Payne et al. [

93], albeit in a preliminary stage, reported that students in Waldorf schools have reduced rates and severity of ADHD. Larrison and Dalya [

65] justifies that, because Waldorf schools employ somatosensorimotor activities related to basal ganglia, which is a brain area related to ADHD. It is also reported that societal reasons that may contribute to ADHD, like early age, poor education, and increased academic expectations [

94], are absent from the Waldorf setting.

4.2.3. Physical Activity-Play

Sibley and Etnier [

95], in an influential meta-analysis of studies pertaining to physical activity and cognition in children, concluded that a significant positive relationship exists between them. The eurythmy class, a unique characteristic of Waldorf education, is reported to provide benefits in coping with stress and fatigue [

21]. Eurythmy also attempts to help students express concepts through movement and sound connecting the mind and body [

86].

In a literature review about the impact of play in children [

96], a number of benefits are reported concerning the cognitive growth of children: developing vocabulary, understanding of different concepts, increased ability to solve problems, increased self-confidence and motivation, and an awareness of the needs of others. In the same review, it is reported that play involving arts develops the fine motor skills of hand and finger control, whereas fantasy play has a therapeutic value. Finally, play that involves contact with nature appears to have a positive effect on recovery from stress and attention fatigue and on mood, concentration, self-discipline, and physiological stress.

Sobo [

20] states that outdoor play is highly valued by Waldorf teachers because of the sensory and motor stimulation it allows. In the same study it is argued that outdoor play contributes to the handling of the changing rhythm and pace by Waldorf teachers, by alternating the quieter classroom activities with the boisterous play action. The outdoor play constitutes an activity that is more and more disappearing from the modern city with great cost to the health, well-being, and achievement of children [

97].

4.2.4. Rhythm

The attention to rhythm, the way students alternate between tasks demanding concentration and more relaxed activities, is vital to Waldorf schools and to neuroeducation principles [

58]. This alternation is likened to “breathing” in and out by the Waldorf teachers. This control of students’ attention, by teachers and schedule, is intentional and it is aimed in they having more concentration during the more structured parts of the day [

78]. The two-hour “main lesson” is a system which incorporates many good principles of “rhythm” or pace and timing [

17]. The teacher is responsible for the pacing of the lesson and, through this management of the rhythm, pupils’ attention spans and capacities for protracted periods of work can be considerably lengthened [

80].

4.2.5. Sleep

Sleep plays an important role in Waldorf education. Every topic presented during the main lesson lasts more than a day; new ideas are usually presented over a three-day period [

80] and are integrated into the main lesson block that lasts 2–4 weeks [

68]. As it is argued by Maquet [

98], sleeping is important for brain plasticity and for learning and memory. Furthermore, procedural memory tasks do not improve performance until hours later and sleep is vital to memory consolidation. The practice of Waldorf teachers of requesting recall of the previous day in oral and written form is related to this theory of connecting sleep to memory and cognition.

4.2.6. Screens and Computers

Today, public worries are targeted towards smartphone use by children and adolescents. There is evidence, hitherto small, that associates smartphone use with negative effects on memory, cognition, attention, and stress [

99]. In this setting, Steiner education with discouraging students from using computers and screens in the early age seems prophetic. The disagreement with the early use of technology, even for educational reasons, comes from the belief that students must learn to perform tasks by themselves first. For example, pupils must learn to draw a map from memory first since the early use of geography software may harm their spatial awareness [

80] (or intelligence as Gardner may point out).

4.2.7. Architecture and Space

Steiner was, among other things, an architect with very distinctive ideas about shapes and colors (goetheanian style-organic shape-relation of colors to developmental stages). Waldorf schools try to follow these ideas in different levels of involvement. Bjørnholt [

100], in her article about the Oslo Waldorf school, writes that

“The rooms are shaped so as to support concentration and immersion in the subject at hand over time, and at the same time, the aesthetic-spatial arrangements mirror and support the growing and developing child.”

There is also an effort to have green spaces, gardens, etc. in the environment of Waldorf schools, wherever this is possible. There are Waldorf schools situated near forest or semi-urban areas [

71], or schools that are in urban areas attempt to reshape the site into a more natural setting [

57]. This effort, as Karjalainen et al. [

101] state, presents benefits that assume that natural settings is related to reducing stress and facilitating recovery from concentration-demanding tasks.

4.2.8. Imitation

Waldorf teachers are expected to be a role model for students, especially in preschool. This has its origins in the developmental theory of Rudolf Steiner, which argues that the child before the age of seven has a strong need and instinct for imitation (an idea also developed by Piaget at a later age). Teaching during these years should be formational but not, as someone may understand it at first sight, that the child must be formed into something else, but rather that teachers should be forming themselves as role-models for the child [

82,

102]. They do that by taking actions, whenever they are observed by children, like sweeping the path and gardening when outdoors [

20]. This need of imitation is related by Waite and Rees [

78] to the emergence of “mirror neuron theory” in neuroscience, which associates imitation to cognition, an association that also has its opponents [

103].

4.2.9. Stress, Emotion, and Cognition

The connection between emotion and cognition is something that it is easily accepted by teachers but not fully researched yet. Teachers recognize that the success of a student in a class depends on his/her emotional state. The relationship between teacher and student is also critical for the students to succeed [

104]. Immordino-Yang and Damasio [

105] explored how cognition is subject to emotion and how they interact with each other. In Immordino-Yang [

106], it is also described how students of disadvantaged areas found a new meaning in learning science when they felt that the lesson was relevant to their emotional experiences (diversity and ethnic identities). Likewise, Ashley [

17] describes students in Waldorf schools situated in deprived districts as achieving better grade results than their mainstream peers because of the stable teacher-students relationship. The eight years this relationship lasts allows for deep trust and appreciation and a feeling of belonging [

82]. Early life stress was indicated by Pechtel and Pizzagalli [

107] to have a major impact on the cognitive and affective function. Waldorf schools are described as schools that attempt to reduce stressful activities [

80,

86].

5. Discussion

The results showed that most of the studies were associated with the linguistic intelligence and with the spatial intelligence. This is not surprising because of the strong oral tradition of Waldorf schools and the importance of drawing and art in these schools [

17].

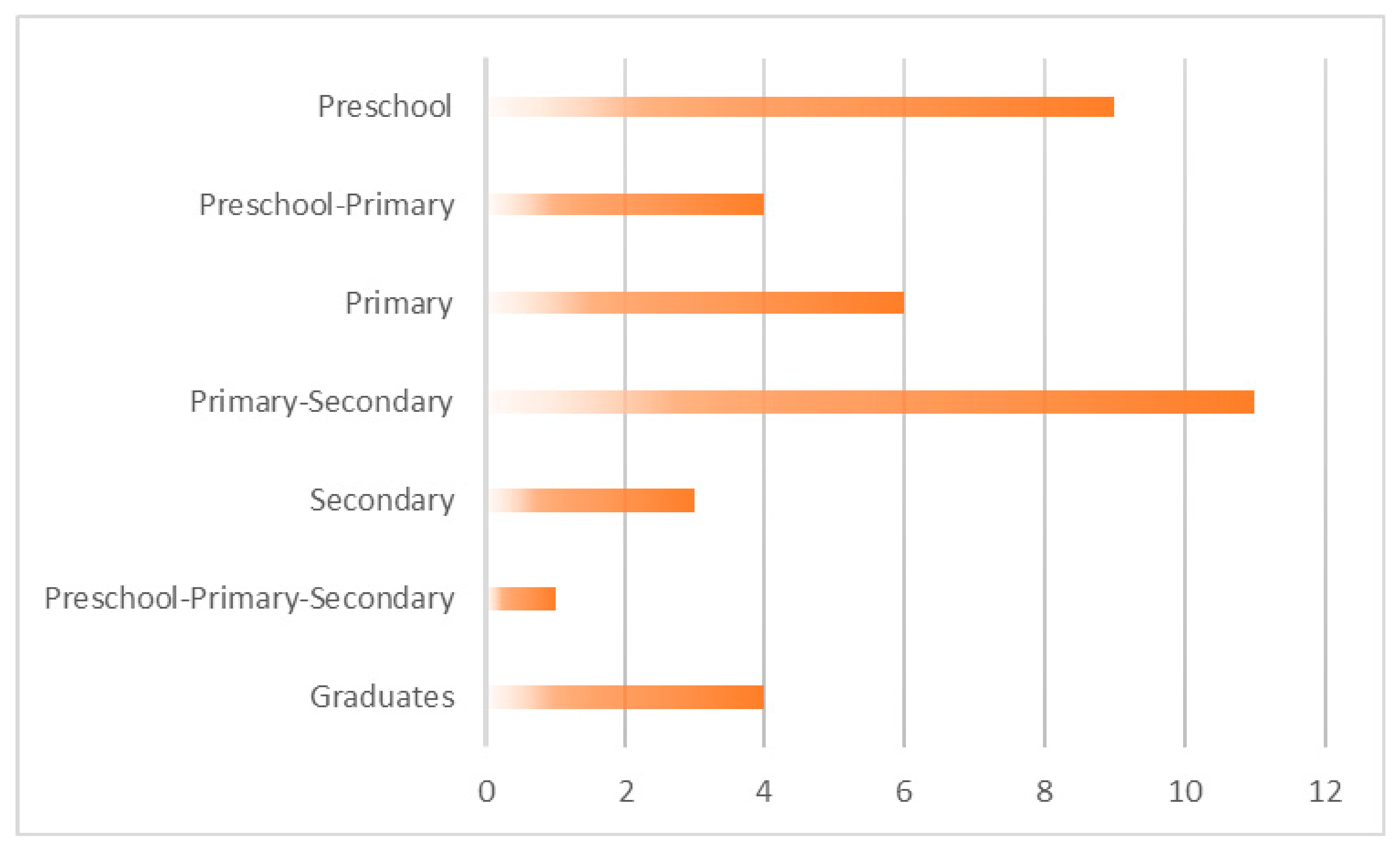

Most of the studies were about preschool education as well as primary-secondary. These school levels cover the developmental stages significant to Steiner, i.e., from the time when the child is between 3 and 7 years old (preschool), to the second developmental stage between 7 and 14 years old (primary and early secondary), until students finally pass to the adolescent phase of their life.

Figure 5 shows the correlation of Waldorf schools with intelligences after considering the level of school.

Figure 5 illustrates that, in the preschool setting, most of the studies related Waldorf with spatial, interpersonal, naturalist, and spiritual-existential (other) intelligence as well as with linguistic and bodily-kinesthetic (preschool-primary). Indeed, the Steiner-Waldorf early childhood approach considers the interdependence of physical, social, emotional, spiritual, and cognitive development [

82]. Children are highly involved with painting and drawing, which helps them acquire balance and symmetry skills (spatial and bodily-kinesthetic intelligence) as well as with playing activities [

68]. During play, children participate in physical exercise or carry out craft activities, which develop fine motor skills (bodily-kinesthetic) [

40]. Play also allows them to communicate with other children; in addition, imitation is fostered, which is one of the most effective and natural means of developing social skills and awareness of others at this age (interpersonal) [

78]. Oral narrative is also central to Waldorf education. Through the rich language of fairy tales, children are building their vocabularies. Moreover, children can tell a story by “reading” the pictures in a book, which develops verbal skills and encourages them to use their own words [

68]. Many children are also participating in puppet shows, thus developing dramatic skills through working with narrative and dialogue in an artistic way (linguistic). In addition, traditional fairy tales and nature stories fill children with a world of feelings, while they gradually evoke a fine moral sense for knowing right from wrong (intrapersonal). In Waldorf setting, children are also encouraged to appreciate the natural world, since the beauty of nature, animals, insects, and plants are brought to them with a feeling of respect and wonder. Besides this, the use of natural materials (wool, wood, felt, cotton) in play and craft fosters a connection with the natural world. All these help children value the gifts of nature (naturalist) [

20]. The Waldorf kindergarten day has different “moods.” There are moments of reverence each day when the children associate the mood with stillness, awe, and wonder (spiritual). Music and movement are introduced by letting children experience the musicality of language and its social aspects through playing ring games and eurythmy. Ring games let children enjoy and participate in traditional songs and rhymes, accompanied by rhythmical and routinely performed gestures by imitation of the teacher. Next, children try to recreate these songs, rhymes, and stories as part of their creative play or in puppet shows or theatre. Eurythmy is a form of movement that works with language and music. Moreover, the celebration of festivals provides experiences of different cultures, so children learn songs and rhymes in many languages as part of regular activity (musical).

As regards the second developmental stage between 7 and 14 years old (primary and early secondary),

Figure 5 shows that several studies associated Waldorf with all intelligences. Some of them are given special attention, such as linguistic and spatial (primary) as well as logical-mathematical, interpersonal, and intrapersonal (primary-secondary). Indeed, as the child moves from preschool education to primary education setting, there is a shift to the development of their linguistic intelligence [

42]. This is attributed to the start of learning how to read and write after the age of seven. Spatial intelligence also plays an important role until the conclusion of the primary education stage, since the artistic immersion continues.

One goal of Waldorf education is linking any knowledge gained to life experiences. For instance, science education starts with stories about the living world. This helps children use their imagination, which, according to Steiner, is an area that must be cultivated during the second developmental stage. The use of children’s imagination is vital because they form a personal experience with the subject taught and this makes the knowledge “live” for a longer time [

85]. Another aspect of science teaching is the importance bestowed to observation, a feature influenced by Goethe [

108]. Students, during early primary grades, observe and describe the living world. Zoology, botany, and human studies are introduced as subjects in a later stage. Only at later grades are chemistry, physics, and other more abstract subjects integrated to the curriculum. A similar approach is followed with mathematics. Students start with numbers and drawing and then proceed to measurement and geometry. There is also an effort to engage many senses when teaching a subject: counting backwards, in second grade for example, is done while students walk backwards in a circle and multiplying is done with a singing and clapping game [

57].

Consequently, there is activation of imagination and of different intelligences during this kind of teaching that include logical-mathematical, interpersonal, and intrapersonal ones. Only after these essential and easy-to-relate subjects are conquered, are algebra and the more abstract notions of mathematics introduced.

Indeed, the child during the first grades of this stage longs to appear adequate and skilled. The student wants to gain the approval of the teacher and of his or her peers. The lack of testing and the more relaxed environment of Waldorf schools enforce that feeling (intrapersonal). The practice of experiencing the lesson in an artistic way, through painting, singing, or role playing, is another factor that helps children explore their inner selves. The increased value of art in Waldorf education has its basis on Steiner and his belief that it makes students establish a personal connection to the subject and that it creates social bonds between students. This is more important during the middle grades, when the child wants to build friendships and to be included as part of a group. The choirs and theatrical plays, which are a common feature of Waldorf schools, help towards this socialization (interpersonal). Students do not just memorize facts; there is an effort to empathize with the subject, as in role playing biographies of historic persons.

Regarding RQ1, there was a considerable number of articles that showed that Waldorf schools are MI “compatible.” There is an overlap of the teaching practices proposed by MI enthusiasts. The subjects are covered by many ways and art plays a role in every subject from mathematics to physical education as Gardner has proposed [

109]. It is true that the empirical evidence that support MI theory is scarce; only two studies were mentioned in this article. The support for the educational implications of MI theory, on the other hand, by educators is strong [

25].

Regarding RQ2, the number of articles that this review unveiled was considerably smaller. In order to explore this relation, more empirical evidence is needed about Waldorf students and anxiety, stress, concentration, and conditions like dyslexia or dyscalculia. The articles that were examined in this review reported that Waldorf students have reduced rates of ADHD, thus better concentration, a subject of neuroeducation. Children in Waldorf schools start reading and writing later in their lives, a practice that is based on Steiner’s theory. This happens because Steiner believed that play and imagination is more critical to the child than reading or writing. Stress, which is related to the cognitive function, is reported to be low in Waldorf schools.