Initial Training of Primary School Teachers: Development of Competencies for Inclusion and Attention to Diversity

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Inclusion is thus seen as a process that enables due account to be taken of the diversity of needs of all children, youth and adults through increased participation in learning, cultural and community activities, as well as reducing exclusion from and within the sphere of education, and ultimately ending exclusion” (p. 9).

- -

- Competence: valuing the diversity of learners: education is based on a belief in equality, human rights, and democracy for all learners. Meaningful participation of all learners in activities is necessary; it is not enough that they have access to education. It is crucial to identify the most appropriate ways to respond to diversity and to know the terminology and language of inclusion and diversity. Teachers should perform self-assessments of their own beliefs and attitudes and how they influence engagement with the diversity of learners.

- -

- Competence: supporting the whole student: this involves promoting the academic, practical, social, and emotional learning of all students and knowing that teachers’ expectations influence student success. Knowledge of learning models and supports for the learning process is necessary, as well as using alternative teaching methods, flexible teaching and providing feedback to learners. It also includes valuing collaborative work with families and communicating appropriately, both verbally and non-verbally, to respond to the needs of learners, families, and other professionals.

- -

- Competence: teamwork: this refers to valuing the effective participation of parents and families to support students’ learning and recognizing the benefits of working collaboratively with other education professionals and participating in school evaluation and development processes. It implies an approach to teaching that includes working with pupils, parents, other schoolteachers, and support staff as a multi-disciplinary team.

- -

- Competence: developing one’s professional and personal dimension: initial teacher education is the basis for continuous professional learning and development. Teachers must be reflective professionals because teaching is a conflict-resolution activity that requires systematic planning, review, and modification. They need to know methods and strategies for evaluating their own work and performance, as well as being aware of current legislation and regulations and their responsibilities toward students, families, and other professionals.

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Q1: Do university students of the degree in primary education at ULL have the competencies related to inclusion and attention to diversity?

- -

- Q2: Are there differences in the development of competencies on inclusion depending on gender, the year in which they are enrolled, or contact with a person with educational needs?

- -

- Q3: Have the students of this degree developed the knowledge necessary to deal with diversity and be inclusive teachers?

- -

- Q4: Have the students of this degree developed the necessary skills to deal with diversity and be inclusive teachers?

- -

- Q5: Have the students of this degree developed the necessary attitudes for dealing with diversity and being inclusive teachers?

- -

- Q6: Are there differences in the knowledge, skills, and attitudes for inclusion and attention to diversity based on the students’ gender, class attendance, the year in which they are enrolled, or their chosen specialization?

2.1. Participants

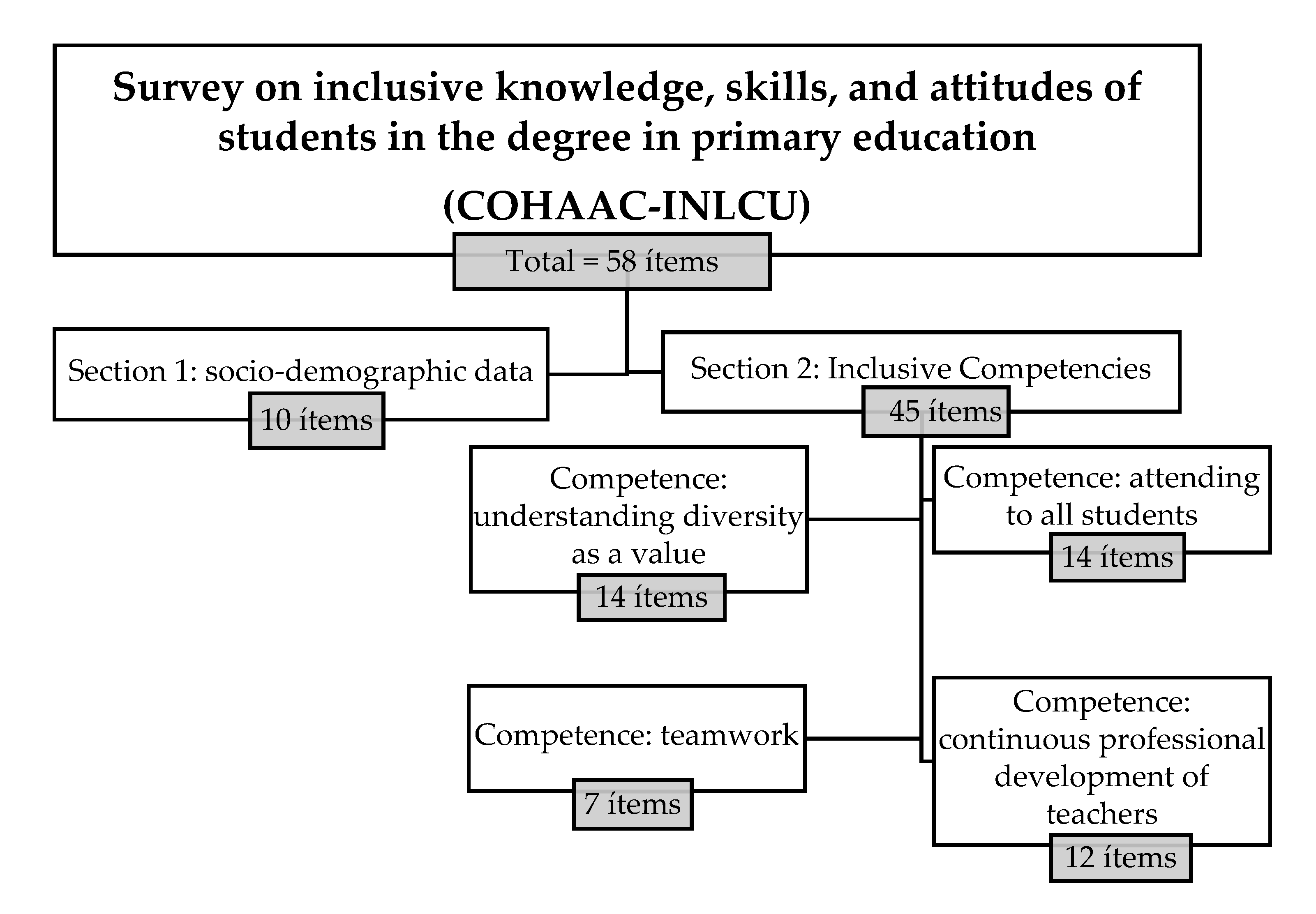

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1. Respond to the diversity of the student | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Student diversity enriches classroom practice. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Students should be given a response, avoiding prejudices based on the different needs they present. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I am concerned that attending to the diversity of students will increase my workload in the classroom. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I have to work for equal rights for all students, regardless of their skills and abilities. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Labeling students can negatively influence their learning. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Inclusive education is for all students, not just those diagnosed with special needs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I have the knowledge to remove barriers that limit the participation of students with needs in the classroom. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I know that in order to respond to diversity it is essential to consider each student in a comprehensive manner (personal, academic, social, emotional factors, etc.). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I know how to adequately use the terminology and language of inclusion and diversity. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I know the factors that condition the inclusion process: educational policies, educational practices, attitudes, etc. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I can identify the student’s learning style in order to offer the best response. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I can identify the learning pace of students to offer them the best response. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I am prepared to contribute to create schools that stimulate learning and achievement of all students. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I believe that the training received during my studies of the Degree in Primary Education has prepared me to be a teacher of all students, regardless of their abilities, interests, gender, social differences, culture, religion, etc. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 2. Attention to all students | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Teacher expectations influence student success. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| It is impossible to properly serve all students in the classroom. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| As a future teacher, I am concerned that students with educational needs are not accepted by the rest of the classmates. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I take into account the social, cultural and ideological background of the students and their families. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I can identify the learning potential of each student, regardless of their educational needs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I am able to provide personalized learning that allows each student to improve his/her competencies. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I am prepared to face the needs that students may present in their learning process. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| The studies of the Degree in Primary Education have allowed me to develop knowledge and skills necessary to teach and evaluate students with different needs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I am able to work individually with students in heterogeneous and diverse classrooms. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I am able to apply in the classroom strategies that promote the participation of all students (teamwork, cooperative work, peer tutoring, etc.). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I have the necessary ability to seek information, resources and support to respond to the educational needs of students. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I am able to adjust and adapt activities to offer the necessary support to all students. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I know how to apply different techniques and strategies to evaluate the performance of students with or without special needs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I am able to apply a variety of teaching methodologies to support the learning of students with and without difficulties. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I am able to implement different modalities of teamwork among students (planning, developing and evaluating them). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 3. Teamwork | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Inclusive education requires teamwork. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I have learned to use strategies to communicate and coordinate with the family and other external professionals (associations, health personnel, etc.) to provide a better response to all students. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I know teamwork techniques to coordinate with other teachers of the center. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I know the terminology and concepts related to the attention to diversity and educational inclusion necessary to work with other special needs support professionals. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I know how to apply conflict resolution strategies with other professionals of the center to coordinate the response to student diversity. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I can work collaboratively to respond to the needs of students with different agents (families, other professionals, specific associations, health personnel, special needs support teachers, etc.). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I have the ability to reflect and put into practice the opinions of other teachers when they are appropriate to improve the educational response. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 4. Permanent professional development of the teaching staff | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I am aware that in order to respond to the diversity of students, continuous training is necessary. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I have learned to critically examine my beliefs about students with educational needs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| A teacher must be knowledgeable in everything related to inclusive education. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| A teacher needs to have specific training to provide an adequate response to diversity. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I know the legal framework that supports inclusive education and attention to diversity. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I have basic knowledge to address the difficulties of students in the classroom. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I master strategies to evaluate the impact of my work on the students’ performance. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I am able to learn from other professionals to improve my inclusive practice. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I am able to learn on my own to improve my knowledge and skills about diversity. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I am sufficiently prepared to adapt my teaching strategies to student diversity. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I know how to use different information and communication technologies (ICT) to provide a better response to all students, with or without special needs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I continually reflect to improve my practice. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

References

- Valcarce, M. De la escuela integradora a la escuela inclusiva. Innovación Educ. 2011, 21, 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, N. Escuela inclusiva: Construcción democrática de sociedad en Chile. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 2011, 55, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.M. Competencias docentes y educación inclusiva. Rev. Electrónica Investig. Educ. 2013, 15, 82–99. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaiz, P. Hacia una educación eficaz para todos: La educación inclusiva. Educar 2000 2002, 5, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, M.A. Supervisión y educación inclusiva. Avances en la Supervisión Educativa: Revista de la Asociación de Inspectores de Educación De España 2011, 14, 1–14. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura UNESCO. Directrices Sobre Políticas de Inclusión en la Educación; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alegre, O.M. Diversidad Humana y Educación; Aljibe: Málaga, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Alegre, O.M. Educar en la Diversidad: Bases Conceptuales; Grupo Editorial Universitario: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Alegre, O.M.; Villar, L.M. Inclusión e Interculturalidad. Un estudio en el marco de la enseñanza universitaria. Rev. Nac. E Int. Educ. Inclusiva 2015, 8, 12–29. [Google Scholar]

- Vélaz, C.; Vaillant, D. Aprendizaje Y Desarrollo Profesional Docente; Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura (OEI); Fundación Santillana: Madrid, Spain, 2009. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Izuzquiza, D.; Echeita, G.; Simón, C. La percepción de estudiantes egresados de magisterio en la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid sobre su competencia profesional para ser “profesorado inclusivo”: Un estudio preliminar. Tend. Pedagógicas 2015, 26, 197–216. [Google Scholar]

- Barceló, M.; López, E.; Camilli, C. Análisis de las competencias genéricas del docente de educación primaria. Estudio de caso. In Las Competencias Básicas. Competencias Profesionales Del Docente; Nieto, E., Callejas, A., Jerez, O., Eds.; Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha: Ciudad Real, España, 2012; pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hollins, E. Teacher preparation for quality teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 2011, 62, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesquero, E.; Sánchez, M.; González, M.; Martín, R.; Guardia, S.; Cervelló, J.; Fernández, P.; Martínez, M.; Varela, P. Las competencias profesionales de los maestros de Primaria. Rev. Española Pedagog. 2008, 241, 447–466. [Google Scholar]

- Granada, M.; Pomés, M.; Sanhueza, S. Actitud de los profesores hacia la inclusión educativa. Pap. Trabajo. Cent. Estud. Interdiscip. Etnolingüística Antropol. Socio-Cult. 2013, 25, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Idol, L. Toward Inclusion of Special Education Students in General Education. A Program Evaluation of Eight Schools. Remedial Espec. Educ. 2006, 27, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, A.; Moliner, O.; Sanchiz, M.L. Actitudes hacia la atención a la diversidad en la formación inicial del profesorado. Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. Form. Del Profr. 2001, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, A.; Díaz, C.; Sanhueza, S.; Friz, M. Percepciones y actitudes de los estudiantes de pedagogía hacia la inclusión educativa. Estud. Pedagógicos 2008, 34, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatori, G.; Mesquita, H.; Rosário, M. Special Education for inclusion in Europe: Critical issues and comparative perspectives for teachers’ education between Italy and Portugal Education. Sci. Soc. 2020, 1, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, O.M.; Villar, L.M. Attitudes of Children with Hearing Loss towards Public Inclusive Education. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education (EADSNE). Formación del Profesorado Para la Educación Inclusiva en Europa. Retos y Oportunidades; Dirección General de Educación y Cultura de la Comisión Europea: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Amr, M.; Al-Natour, M.; Al-Abdallat, B.; Alkhamra, H. Primary school teachers’ knowledge, attitudes and views on barriers to inclusion in Jordan. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2013, 31, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bawa Kuyini, A.; Desai, I.; Sharma, U. Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, attitudes and concerns about implementing inclusive education in Ghana. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 24, 1509–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegalajar, M.C.; Colmenero, M.J. Actitudes y formación docente hacia la inclusión en Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Rev. Electrónica Investig. Educ. 2017, 19, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gil, F.; Martín-Pastor, E.; Flores, N.; Jenaro, C.; Poy, R.; Gómez-Vela, M. Teaching, Learning and inclusive education: The challenge of teachers’ training for inclusión. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 93, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Avramidis, E.; Bayliss, P.; Burden, R. Student teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of children with special educational needs in the ordinary school. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2000, 16, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education (EADSNE). Teacher Education for Inclusion. Profile of Inclusive Teachers; Dirección General de Educación y Cultura de la Comisión Europea: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Ato-García, M.; Vallejo, G. Diseños de Investigación en Psicología; Pirámide: Madrid, España, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández-Collado, C.; Batista, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 6st ed.; McGraw-Hill: Mexico D.F., Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Navas, M.J. Métodos, Diseños Y Técnicas de Investigación Psicológica; UNED: Madrid, España, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura-León, J.; Caycho-Rodríguez, T. El coeficiente Omega: Un método alternativo para la estimación de la confiabilidad. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Niñez Juv. 2017, 15, 625–627. [Google Scholar]

- Viladrich, C.; Angulo-Brunet, A.; Doval, E. Un viaje alrededor de alfa y omega para estimar la fiabilidad de consistencia interna. An. Psicol. 2017, 33, 755–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.Y. The alpha and the omega of scale reliability and validity. Eur. Health Psychol. 2014, 16, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Tomczak, M.; Tomczak, E. The need to report effect size estimates revisited. An overview of some recommended measures of effect size. Trends Sport Sci. 2014, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ballhysa, N.; Flagler, M. A Teachers’ Perspective of Inclusive Education for Students with Special Needs in a Model Demonstration Project. Acad. Int. Sci. J. 2011, 3, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

| Competencies | H | p | Average Ranges | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | ||||

| Responding to the diversity of the student | 24.217 | 0.000 | 0.055 | 190.97 | 229.19 | 221.09 | 277.49 |

| Attention to all students | 32.870 | 0.000 | 0.074 | 191.21 | 229.44 | 211.14 | 291.64 |

| Teamwork | 31.778 | 0.000 | 0.072 | 184.58 | 243.44 | 218.63 | 278.82 |

| Continuous professional development of teachers | 47.403 | 0.000 | 0.107 | 173.85 | 225.60 | 242.72 | 288.88 |

| Competencies | Pairs | Test Statistic | Deviation of the Test Statistic | p | p Adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responding to the diversity of students | 1st–4th | −86.520 | −4.86 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 3rd–4th | −56.402 | −2.40 | 0.003 | 0.020 | |

| Attention to all students | 1st–4th | −100.430 | −5.64 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 2nd–4th | −62.194 | −3.09 | 0.002 | 0.012 | |

| 3rd–4th | −80.496 | −4.19 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Teamwork | 1st–2nd | −58.855 | −3.52 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 1st–4th | −94.239 | −5.29 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 3rd–4th | −60.195 | −3.13 | 0.002 | 0.010 | |

| Continuous professional development of teachers | 1st–2nd | −51.765 | −3.09 | 0.002 | 0.012 |

| 1st–3rd | −68.872 | −4.42 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 1st–4th | −115.031 | −6.46 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 2nd–4th | −63.274 | −3.14 | 0.002 | 0.010 |

| Competencies | H | p | Average Range | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | W | M | WC | ||||

| Responding to the diversity of students | 20.083 | 0.000 | 0.045 | 285.68 | 231.32 | 212.72 | 205.61 |

| Attention to all students | 11.495 | 0.009 | 0.026 | 264.67 | 235.72 | 227.08 | 206.34 |

| Teamwork | 17.596 | 0.001 | 0.040 | 280.83 | 228.43 | 221.69 | 205.31 |

| Continuous professional development of teachers | 27.050 | 0.000 | 0.061 | 297.18 | 230.09 | 206.53 | 204.61 |

| Competencies | Pairs | Test Statistic | Deviation of the Test Statistic | p | p Adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responding to the diversity of students | D–WC | 80.069 | 4.41 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| D–M | 72.959 | 3.11 | 0.002 | 0.011 | |

| Attention to all students | D–WC | 58.326 | 3.21 | 0.001 | 0.008 |

| Teamwork | D–WC | 75.524 | 4.16 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Continuous professional development of teachers | D–WC | 92.560 | 5.10 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| D–W | 67.088 | 2.78 | 0.005 | 0.032 | |

| D–M | 90.641 | 3.87 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arvelo-Rosales, C.N.; Alegre de la Rosa, O.M.; Guzmán-Rosquete, R. Initial Training of Primary School Teachers: Development of Competencies for Inclusion and Attention to Diversity. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080413

Arvelo-Rosales CN, Alegre de la Rosa OM, Guzmán-Rosquete R. Initial Training of Primary School Teachers: Development of Competencies for Inclusion and Attention to Diversity. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(8):413. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080413

Chicago/Turabian StyleArvelo-Rosales, Carmen Nuria, Olga María Alegre de la Rosa, and Remedios Guzmán-Rosquete. 2021. "Initial Training of Primary School Teachers: Development of Competencies for Inclusion and Attention to Diversity" Education Sciences 11, no. 8: 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080413

APA StyleArvelo-Rosales, C. N., Alegre de la Rosa, O. M., & Guzmán-Rosquete, R. (2021). Initial Training of Primary School Teachers: Development of Competencies for Inclusion and Attention to Diversity. Education Sciences, 11(8), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080413