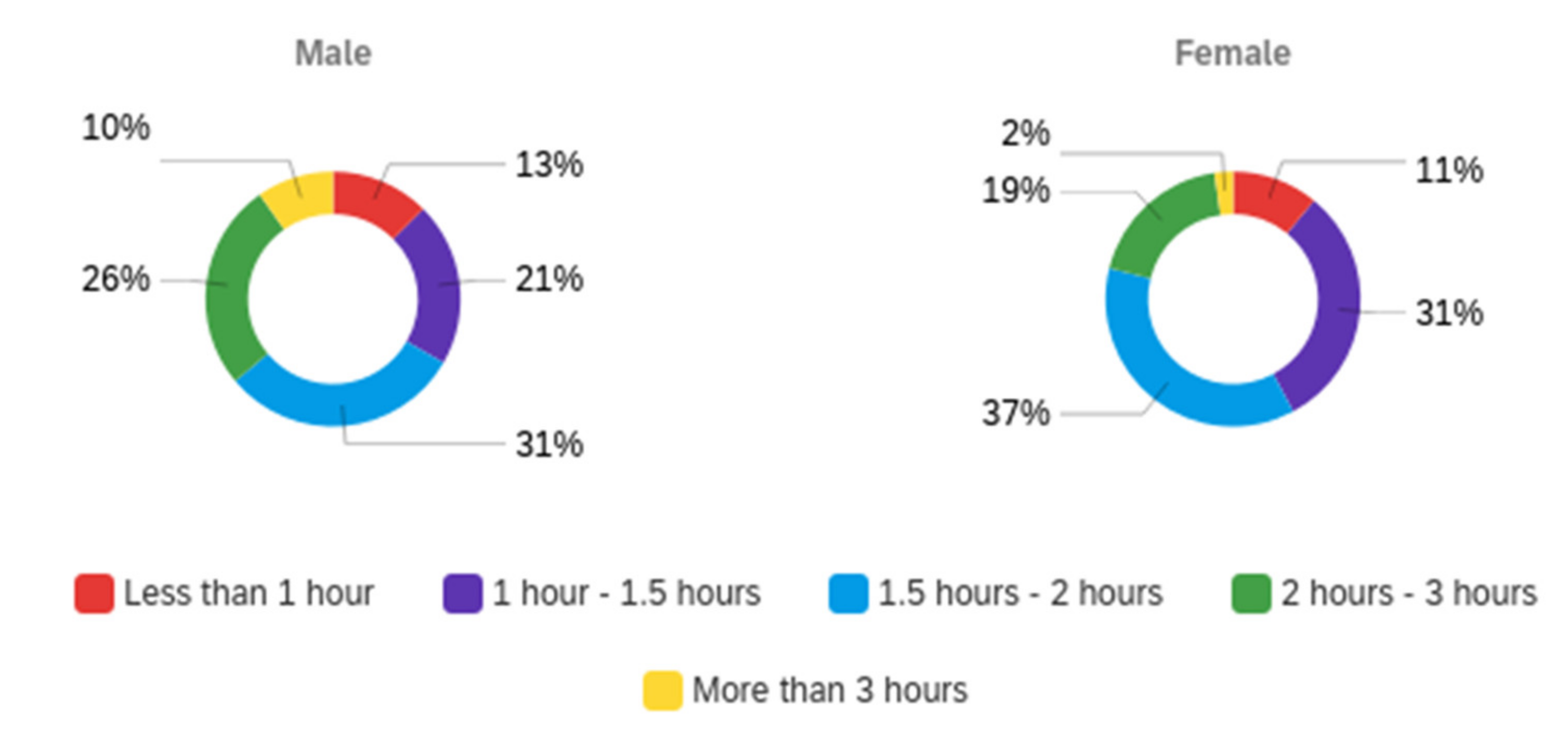

Figure 1.

Breakdown of length of defense by gender, for n = 72 male respondents and n = 128 female respondents.

Figure 1.

Breakdown of length of defense by gender, for n = 72 male respondents and n = 128 female respondents.

Figure 2.

Distribution of numbers of committee members, broken down by gender. n = 70 for the male respondents and n = 128 for the female respondents.

Figure 2.

Distribution of numbers of committee members, broken down by gender. n = 70 for the male respondents and n = 128 for the female respondents.

Figure 3.

Nervousness by gender: (a) before the defense, (b) during the defense, and (c) after the defense and before receiving the outcome. n = 200 for before the defense, with n = 128 female respondents and n = 71 male respondents, n = 197 for during the defense, with n = 124 female respondents and n = 72 male respondents, and n = 175 for after the defense, with n = 111 female respondents and n = 63 male respondents. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 3.

Nervousness by gender: (a) before the defense, (b) during the defense, and (c) after the defense and before receiving the outcome. n = 200 for before the defense, with n = 128 female respondents and n = 71 male respondents, n = 197 for during the defense, with n = 124 female respondents and n = 72 male respondents, and n = 175 for after the defense, with n = 111 female respondents and n = 63 male respondents. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 4.

Enjoyment of the defense on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by gender. n = 197, with n = 126 female respondents and n = 71 male respondents. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 4.

Enjoyment of the defense on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by gender. n = 197, with n = 126 female respondents and n = 71 male respondents. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 5.

Perceived difficulty of the defense on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by gender. n = 200, with n = 129 female respondents and n = 71 male respondents. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 5.

Perceived difficulty of the defense on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by gender. n = 200, with n = 129 female respondents and n = 71 male respondents. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 6.

Nervousness before the defense on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by ethnicity. n = 193, with n = 142 white, n = 7 Black or African American, n = 15 Asian, n = 12 Latinx, n = 1 First Nations, n = 4 mixed, and n = 12 other. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 6.

Nervousness before the defense on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by ethnicity. n = 193, with n = 142 white, n = 7 Black or African American, n = 15 Asian, n = 12 Latinx, n = 1 First Nations, n = 4 mixed, and n = 12 other. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 7.

Affective dimensions of the defense correlated to ethnicity: (a) Enjoyment of the defense proceedings on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by ethnicity. n = 194, with n = 141 white, n = 7 Black or African American, n = 15 Asian, n = 12 Latinx, n = 1 First Nations, n = 4 mixed, and n = 14 other, (b) Perceived seriousness of the defense proceedings on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by ethnicity. n = 195, with n = 141 white, n = 7 Black or African American, n = 15 Asian, n = 13 Latinx, n = 1 First Nations, n = 4 mixed, and n = 14 other. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 7.

Affective dimensions of the defense correlated to ethnicity: (a) Enjoyment of the defense proceedings on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by ethnicity. n = 194, with n = 141 white, n = 7 Black or African American, n = 15 Asian, n = 12 Latinx, n = 1 First Nations, n = 4 mixed, and n = 14 other, (b) Perceived seriousness of the defense proceedings on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by ethnicity. n = 195, with n = 141 white, n = 7 Black or African American, n = 15 Asian, n = 13 Latinx, n = 1 First Nations, n = 4 mixed, and n = 14 other. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 8.

Overall value of the defense as part of the doctoral experience on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by ethnicity. n = 197, with n = 143 white, n = 7 Black or African American, n = 15 Asian, n = 13 Latinx, n = 1 First Nations, n = 4 mixed, and n = 14 other. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 8.

Overall value of the defense as part of the doctoral experience on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by ethnicity. n = 197, with n = 143 white, n = 7 Black or African American, n = 15 Asian, n = 13 Latinx, n = 1 First Nations, n = 4 mixed, and n = 14 other. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 9.

Nervousness by age group: (a) before the defense, (b) during the defense, and (c) after the defense and before receiving the outcome. n = 193 for before the defense, with n = 5 < 26, n = 75 26–30, n = 61 31–35, n = 26 36–40, n = 11 41–45, n = 8 46–50, n = 7 > 50. n = 190 for during the defense, with n = 5 < 26, n = 74 26–30, n = 59 31–35, n = 26 36–40, n = 11 41–45, n = 8 46–50, n = 7 > 50. n = 168 for after the defense and before knowing the outcome, with n = 5 < 26, n = 66 26–30, n = 52 31–35, n = 21 36–40, n = 10 41–45, n = 7 46–50, n = 7 >50. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 9.

Nervousness by age group: (a) before the defense, (b) during the defense, and (c) after the defense and before receiving the outcome. n = 193 for before the defense, with n = 5 < 26, n = 75 26–30, n = 61 31–35, n = 26 36–40, n = 11 41–45, n = 8 46–50, n = 7 > 50. n = 190 for during the defense, with n = 5 < 26, n = 74 26–30, n = 59 31–35, n = 26 36–40, n = 11 41–45, n = 8 46–50, n = 7 > 50. n = 168 for after the defense and before knowing the outcome, with n = 5 < 26, n = 66 26–30, n = 52 31–35, n = 21 36–40, n = 10 41–45, n = 7 46–50, n = 7 >50. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 10.

Perceived difficulty of the defense on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by age group. n = 194, with n = 5 < 26, n =77 26–30, n = 61 31–35, n = 26 36–40, n = 10 41–45, n = 8 46–50, n = 7 > 50. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 10.

Perceived difficulty of the defense on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by age group. n = 194, with n = 5 < 26, n =77 26–30, n = 61 31–35, n = 26 36–40, n = 10 41–45, n = 8 46–50, n = 7 > 50. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 11.

Overall value of the defense as part of the doctoral experience on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by age group. n = 194, with n = 5 < 26, n = 77 26–30, n = 60 31–35, n = 26 36–40, n = 11 41–45, n = 8 46–50, n = 7 > 50. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 11.

Overall value of the defense as part of the doctoral experience on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by age group. n = 194, with n = 5 < 26, n = 77 26–30, n = 60 31–35, n = 26 36–40, n = 11 41–45, n = 8 46–50, n = 7 > 50. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 12.

Perceived seriousness of defense proceedings on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by current position. n = 199, with n = 151 in academia, n = 28 in industry or as business owner, n = 8 in government, n = 5 employed otherwise, and n = 7 unemployed. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 12.

Perceived seriousness of defense proceedings on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by current position. n = 199, with n = 151 in academia, n = 28 in industry or as business owner, n = 8 in government, n = 5 employed otherwise, and n = 7 unemployed. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 13.

Overall value of the defense as part of the doctoral experience on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by current position. n = 201, n = 153 in academia, n = 28 in industry or as business owner, n = 8 in government, n = 5 employed otherwise, and n = 7 unemployed. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 13.

Overall value of the defense as part of the doctoral experience on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by current position. n = 201, n = 153 in academia, n = 28 in industry or as business owner, n = 8 in government, n = 5 employed otherwise, and n = 7 unemployed. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 14.

Enjoyment of defense on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by field of study. n = 196, with n = 45 in life sciences, n = 27 in humanities and arts, n = 59 in social sciences, n = 56 in STEM, and n = 9 in multidisciplinary fields. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 14.

Enjoyment of defense on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by field of study. n = 196, with n = 45 in life sciences, n = 27 in humanities and arts, n = 59 in social sciences, n = 56 in STEM, and n = 9 in multidisciplinary fields. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 15.

Perceived formality of defense on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by field of study. n = 198, with n = 46 in life sciences, n = 26 in humanities and arts, n = 59 in social sciences, n = 58 in STEM, and n = 9 in multidisciplinary fields. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 15.

Perceived formality of defense on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by field of study. n = 198, with n = 46 in life sciences, n = 26 in humanities and arts, n = 59 in social sciences, n = 58 in STEM, and n = 9 in multidisciplinary fields. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 16.

Overall value of the defense as part of the doctoral journey on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by field of study. n = 199, with n = 46 in life sciences, n = 27 in humanities and arts, n = 60 in social sciences, n = 57 in STEM, and n = 9 in multidisciplinary fields. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Figure 16.

Overall value of the defense as part of the doctoral journey on a 0–10 Likert scale, broken down by field of study. n = 199, with n = 46 in life sciences, n = 27 in humanities and arts, n = 60 in social sciences, n = 57 in STEM, and n = 9 in multidisciplinary fields. The red line in the boxplot indicates the median, and the blue dot indicates the mean value.

Table 1.

Matrix of analysis between categories of sociodemographic properties and categories of student perception.

Table 1.

Matrix of analysis between categories of sociodemographic properties and categories of student perception.

| | Sociodemographic Elements | Student’s Perception of Defense |

|---|

| 1 | Gender | Nervousness |

| 2 | Ethnicity | Enjoyment |

| 3 | Age at obtaining the doctorate | Perceived fairness of committee |

| 4 | Current position | Perceived committee suitability |

| 5 | Field of study | Perceived importance |

| 6 | | Difficulty of defense |

| 7 | | Formality of defense |

| 8 | | Seriousness of defense proceedings |

| 9 | | Purpose of defense |

| 10 | | Perceived academic competence after defense |

| 11 | | Desire to continue in field after defense |

| 12 | | Desire to remain in academia after defense |

| 13 | | Perceived publishability of research after defense |

| 14 | | Overall perception of defense as valuable experience |

Table 2.

Sociodemographic aspects of survey respondents, broken down by gender. Note, no respondents self-identified as “Other/prefer not to say” gender.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic aspects of survey respondents, broken down by gender. Note, no respondents self-identified as “Other/prefer not to say” gender.

| | Total | Male | Female |

|---|

| | n = 204 | n = 72 | n = 130 |

| Ethnicity | n = 199 | n = 71 | n = 128 |

| White | 72% | 59% | 80% |

| Black or African American | 4% | 4% | 3% |

| Asian | 8% | 10% | 7% |

| Latinx/Hispanic | 7% | 11% | 4% |

| First Nations | 1% | 1% | 0% |

| Mixed | 2% | 1% | 2% |

| Other | 7% | 13% | 4% |

| Current employment | n = 202 | n = 72 | n = 129 |

| Academia | 76% | 75% | 78% |

| Industry and business | 14% | 14% | 13% |

| Government | 4% | 4% | 4% |

| Unemployed | 3% | 4% | 3% |

| Other | 2% | 3% | 2% |

| Age at the defense | n = 195 | n = 70 | n = 125 |

| <26 | 3% | 4% | 2% |

| 26–30 | 39% | 33% | 43% |

| 31–35 | 31% | 41% | 26% |

| 36–40 | 13% | 14% | 13% |

| 41–45 | 6% | 4% | 6% |

| 46–50 | 4% | 3% | 5% |

| >50 | 4% | 0% | 6% |

| Field of study | n = 201 | n = 72 | n = 128 |

| Life sciences | 23% | 15% | 27% |

| Humanities and arts | 14% | 10% | 17% |

| Social sciences | 30% | 18% | 37% |

| STEM | 28% | 56% | 13% |

| Multidisciplinary | 4% | 1% | 6% |

Table 3.

Committee fairness and suitability, by gender.

Table 3.

Committee fairness and suitability, by gender.

| | Male | Female |

|---|

| Did you consider your committee fair? |

| | n = 71 | n = 128 |

| Yes | 92.96% | 79.69% |

| To some extent | 5.63% | 19.53% |

| No | 1.41% | 0.78% |

| Did you consider your committee suitable for making a well-balanced assessment of your work? |

| | n = 72 | n = 129 |

| Yes | 84.72% | 77.52% |

| To some extent | 15.28% | 20.16% |

| No | 0.00% | 2.33% |

Table 4.

Long-term impact of defense on student perception, by gender.

Table 4.

Long-term impact of defense on student perception, by gender.

| | Male | Female |

|---|

| How did your defense influence your perception of your academic competence? |

| | n = 72 | n = 129 |

| Increased | 62.50% | 53.49% |

| Not affected | 30.56% | 36.43% |

| Decreased | 6.94% | 10.08% |

| How did your defense influence your desire to continue to work in the sphere of your PhD research? |

| | n = 72 | n = 129 |

| Increased | 34.72% | 30.23% |

| Not affected | 59.72% | 60.47% |

| Decreased | 5.56% | 9.30% |

| How did your defense influence your desire to work in academia? |

| | n = 72 | n = 129 |

| Increased | 37.50% | 23.26% |

| Not affected | 56.94% | 65.12% |

| Decreased | 5.57% | 11.63% |

| How did your defense influence your perception on the publishability of your research? |

| | n = 72 | n = 129 |

| Increased | 40.28% | 37.98% |

| Not affected | 55.56% | 50.39% |

| Decreased | 4.17% | 11.63% |

Table 5.

Committee fairness and suitability, by ethnicity.

Table 5.

Committee fairness and suitability, by ethnicity.

| | White | Black or African American | Asian | Latinx | First Nations | Mixed | Other |

|---|

| Did you consider your committee fair? |

| | n = 143 | n = 7 | n = 15 | n = 12 | n = 1 | n = 4 | n = 14 |

| Yes | 80.42% | 100% | 100% | 83.33% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| To some extent | 18.18% | 0% | 0% | 16.67% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| No | 1.40% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Did you consider your committee suitable for making a well-balanced assessment of your work? |

| | n = 144 | n = 7 | n = 15 | n = 13 | n = 1 | n = 4 | n = 14 |

| Yes | 77.78% | 85.71% | 80.00% | 84.62% | 100% | 100% | 92.86% |

| To some extent | 20.14% | 14.29% | 20.00% | 15.38% | 0% | 0% | 7.14% |

| No | 2.08% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Table 6.

Long-term impact of defense on student perception, by ethnicity.

Table 6.

Long-term impact of defense on student perception, by ethnicity.

| | White | Black or African American | Asian | Latinx | First Nations | Mixed | Other |

|---|

| How did your defense influence your perception of your academic competence? |

| | n = 144 | n = 7 | n = 15 | n = 13 | n = 1 | n = 4 | n = 14 |

| Increased | 50.69% | 57.14% | 80.00% | 76.92% | 0% | 75.00% | 64.29% |

| Not affected | 40.28% | 28.57% | 13.33% | 15.38% | 100% | 25.00% | 21.43% |

| Decreased | 9.03% | 14.29% | 6.67% | 7.69% | 0% | 0% | 14.29% |

| How did your defense influence your desire to continue to work in the sphere of your PhD research? |

| | n = 144 | n = 7 | n = 15 | n = 13 | n = 1 | n = 4 | n = 14 |

| Increased | 31.25% | 57.14% | 40.00% | 23.08% | 0% | 50% | 21.43% |

| Not affected | 61.81% | 28.57% | 60.00% | 46.15% | 100% | 50% | 71.43% |

| Decreased | 6.94% | 14.29% | 0% | 30.77% | 0% | 0% | 7.14% |

| How did your defense influence your desire to work in academia? |

| | n = 144 | n = 7 | n = 15 | n = 13 | n = 1 | n = 4 | n = 14 |

| Increased | 24.31% | 42.86% | 40.00% | 30.77% | 0% | 50% | 42.86% |

| Not affected | 65.28% | 57.14% | 60.00% | 53.85% | 100% | 50% | 42.86% |

| Decreased | 10.42% | 0% | 0% | 15.38% | 0% | 0% | 14.29% |

| How did your defense influence your perception on the publishability of your research? |

| | n = 144 | n = 7 | n = 15 | n = 13 | n = 1 | n = 4 | n = 14 |

| Increased | 38.19% | 42.86% | 40.00% | 46.15% | 0% | 50% | 42.86% |

| Not affected | 52.78% | 28.57% | 53.33% | 46.15% | 100% | 50% | 50.00% |

| Decreased | 9.03% | 28.57% | 6.67% | 7.69% | 0% | 0% | 7.14% |

Table 7.

Committee fairness and suitability, by age at the defense.

Table 7.

Committee fairness and suitability, by age at the defense.

| | <26 | 26–30 | 31–35 | 36–40 | 41–45 | 46–50 | >50 |

|---|

| Did you consider your committee fair? |

| | n = 5 | n = 75 | n = 61 | n = 26 | n = 11 | n = 8 | n = 7 |

| Yes | 100% | 85.33% | 85.25% | 80.77% | 81.82% | 75% | 85.71% |

| To some extent | 0% | 14.67% | 14.75% | 11.54% | 18.18% | 25% | 14.29% |

| No | 0% | 0% | 0% | 7.69% | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Did you consider your committee suitable for making a well-balanced assessment of your work? |

| | n = 5 | n = 77 | n = 61 | n = 26 | n = 11 | n = 8 | n = 7 |

| Yes | 100% | 83.12% | 80.33% | 80.77% | 72.73% | 87.50% | 71.43% |

| To some extent | 0% | 16.88% | 16.39% | 19.23% | 27.27% | 12.50% | 14.29% |

| No | 0% | 0% | 3.28% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 14.29% |

Table 8.

Long-term impact of defense on student perception, by age at the defense.

Table 8.

Long-term impact of defense on student perception, by age at the defense.

| | <26 | 26–30 | 31–35 | 36–40 | 41–45 | 46–50 | >50 |

|---|

| How did your defense influence your perception of your academic competence? |

| | n = 5 | n = 77 | n = 61 | n = 26 | n = 11 | n = 8 | n = 7 |

| Increased | 100% | 50.65% | 62.30% | 53.85% | 27.27% | 75.00% | 71.43% |

| Not affected | 0% | 36.36% | 32.79% | 38.46% | 63.64% | 12.50% | 14.29% |

| Decreased | 0% | 12.99% | 4.92% | 7.69% | 9.09% | 12.50% | 14.29% |

| How did your defense influence your desire to continue to work in the sphere of your PhD research? |

| | n = 5 | n = 77 | n = 61 | n = 26 | n = 11 | n = 8 | n = 7 |

| Increased | 20% | 29.87% | 34.43% | 42.31% | 0% | 25.00% | 42.86% |

| Not affected | 80% | 59.74% | 60.66% | 53.85% | 81.82% | 62.50% | 42.86% |

| Decreased | 0% | 10.39% | 4.92% | 3.85% | 18.18% | 12.50% | 14.29% |

| How did your defense influence your desire to work in academia? |

| | n = 5 | n = 77 | n = 61 | n = 26 | n = 11 | n = 8 | n = 7 |

| Increased | 40% | 25.97% | 27.87% | 34.62% | 18.18% | 37.50% | 28.57% |

| Not affected | 60% | 61.04% | 63.93% | 61.54% | 72.73% | 62.50% | 42.86% |

| Decreased | 0% | 12.99% | 8.20% | 3.85% | 9.09% | 0% | 28.57% |

| How did your defense influence your perception on the publishability of your research? |

| | n = 5 | n = 77 | n = 61 | n = 26 | n = 11 | n = 8 | n = 7 |

| Increased | 20% | 36.36% | 42.62% | 38.46% | 36.36% | 50.00% | 42.86% |

| Not affected | 60% | 55.84% | 52.46% | 50.00% | 45.45% | 37.50% | 28.57% |

| Decreased | 20% | 7.79% | 4.92% | 11.54% | 18.18% | 12.50% | 28.57% |

Table 9.

Committee fairness and suitability, by current position.

Table 9.

Committee fairness and suitability, by current position.

| | Academia | Industry or Business Owner | Government | Other | Unemployed |

|---|

| Did you consider your committee fair? |

| | n = 152 | n = 28 | n = 8 | n = 5 | n = 7 |

| Yes | 85.53% | 75% | 87.5% | 80% | 85.71% |

| To some extent | 13.82% | 25% | 12.5% | 0% | 14.29% |

| No | 0.66% | 0% | 0% | 20% | 0% |

| Did you consider your committee suitable for making a well-balanced assessment of your work? |

| | n = 154 | n = 28 | n = 8 | n = 5 | n = 7 |

| Yes | 80.52% | 78.57% | 75% | 40% | 100% |

| To some extent | 18.18% | 21.43% | 12.5% | 60% | 0% |

| No | 1.30% | 0% | 12.5% | 0% | 0% |

Table 10.

Long-term impact of defense on student perception, by current position.

Table 10.

Long-term impact of defense on student perception, by current position.

| | Academia | Industry or Business Owner | Government | Other | Unemployed |

|---|

| How did your defense influence your perception of your academic competence? |

| | n = 154 | n = 28 | n = 8 | n = 5 | n = 7 |

| Increased | 57.79% | 50.00% | 50.00% | 40% | 85.71% |

| Not affected | 33.77% | 35.71% | 37.50% | 60% | 14.29% |

| Decreased | 8.44% | 14.29% | 12.50% | 0% | 0% |

| How did your defense influence your desire to continue to work in the sphere of your PhD research? |

| | n = 154 | n = 28 | n = 8 | n = 5 | n = 7 |

| Increased | 33.12% | 17.86% | 12.50% | 60% | 57.14% |

| Not affected | 58.44% | 75.00% | 75.00% | 40% | 42.86% |

| Decreased | 8.44% | 7.14% | 12.50% | 0% | 0% |

| How did your defense influence your desire to work in academia? |

| | n = 154 | n = 28 | n = 8 | n = 5 | n = 7 |

| Increased | 31.17% | 10.71% | 0% | 40% | 57.14% |

| Not affected | 61.69% | 71.43% | 75% | 40% | 42.86% |

| Decreased | 7.14% | 17.86% | 25% | 20% | 0% |

| How did your defense influence your perception on the publishability of your research? |

| | n = 154 | n = 28 | n = 8 | n = 5 | n = 7 |

| Increased | 40.91% | 21.43% | 37.5% | 40% | 57.14% |

| Not affected | 49.35% | 71.43% | 50% | 60% | 42.86% |

| Decreased | 9.74% | 7.14% | 12.5% | 0% | 0% |

Table 11.

Committee fairness and suitability, by field of study.

Table 11.

Committee fairness and suitability, by field of study.

| | Life Sciences | Humanities and Arts | Social Sciences | STEM | Multidisciplinary |

|---|

| Did you consider your committee fair? |

| | n = 45 | n = 28 | n = 60 | n = 57 | n = 9 |

| Yes | 88.89% | 64.29% | 86.67% | 89.47% | 66.67% |

| To some extent | 11.11% | 32.14% | 11.67% | 10.53% | 33.33% |

| No | 0% | 3.57% | 1.67% | 0% | 0% |

| Did you consider your committee suitable for making a well-balanced assessment of your work? |

| | n = 46 | n = 28 | n = 60 | n = 58 | n = 9 |

| Yes | 82.61% | 67.86% | 83.33% | 84.48% | 44.44% |

| To some extent | 15.22% | 32.14% | 13.33% | 15.52% | 55.56% |

| No | 2.17% | 0% | 3.33% | 0% | 0% |

Table 12.

Long-term impact of defense on student perception, by field of study.

Table 12.

Long-term impact of defense on student perception, by field of study.

| | Life Sciences | Humanities and Arts | Social Sciences | STEM | Multidisciplinary |

|---|

| How did your defense influence your perception of your academic competence? |

| | n = 46 | n = 28 | n = 60 | n = 58 | n = 9 |

| Increased | 47.83% | 50% | 60% | 70.69% | 22.22% |

| Not affected | 45.65% | 25% | 35% | 22.41% | 66.67% |

| Decreased | 6.52% | 25% | 5% | 6.90% | 11.11% |

| How did your defense influence your desire to continue to work in the sphere of your PhD research? |

| | n = 46 | n = 28 | n = 60 | n = 58 | n = 9 |

| Increased | 28.26% | 39.29% | 25.00% | 37.93% | 22.22% |

| Not affected | 60.87% | 39.29% | 73.33% | 58.62% | 55.56% |

| Decreased | 10.87% | 21.43% | 1.67% | 3.45% | 22.22% |

| How did your defense influence your desire to work in academia? |

| | n = 46 | n = 28 | n = 60 | n = 58 | n = 9 |

| Increased | 32.61% | 25.00% | 18.33% | 37.93% | 11.11% |

| Not affected | 56.52% | 46.43% | 78.33% | 55.17% | 88.89% |

| Decreased | 10.87% | 28.57% | 3.33% | 6.90% | 0% |

| How did your defense influence your perception on the publishability of your research? |

| | n = 46 | n = 28 | n = 60 | n = 58 | n = 9 |

| Increased | 32.61% | 32.14% | 50.00% | 36.21% | 22.22% |

| Not affected | 56.52% | 39.29% | 46.67% | 62.07% | 55.56% |

| Decreased | 10.87% | 28.57% | 3.33% | 1.72% | 22.22% |