Abstract

This study examined Finnish eighth graders’ (N = 1136) educational aspirations and how those can be predicted by mindsets, academic achievement, and gender. Multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate how two mindset constructs (intelligence and giftedness), domain-specific academic performance (mathematics and reading), and gender relate to students’ educational aspirations on three levels (academic, vocational, and unknown). The growth mindset about giftedness was found to predict unknown aspirations, whereas the growth mindset about intelligence did not predict educational aspirations. High performance in math predicted students’ academic aspirations, but performance in reading did not predict educational aspirations. Gender-related differences were found, as boys seem to have vocational aspirations, but the effect did not penetrate all schools. Lastly, students’ aspirations differed between schools: from some schools, students are more likely to apply to university, while from other schools, students are more likely to apply to vocational education. Overall, the study demonstrated that a growth mindset does not directly predict academic aspirations, and the relationship between implicit beliefs and educational outcomes might be more complex than suggested.

1. Introduction

Students′ self-concepts are shown to predict the selection of educational tracks, aspirations, and future occupations and are influenced by perceptions regarding the ability to master schooling [1,2]. Carol Dweck [3,4] has suggested that academic goal orientations are related to implicit theories about intellectual ability, which can explain the variations in students’ engagement, persistence, and achievement in education. Implicit theories produce a framework that influences how individuals process information and develop opinions about their abilities [5].

In Dweck’s mindset theory, mindset refers to people’s core beliefs about human attributes and abilities, such as personality and intelligence [6] and it is said to indicate how people respond to setbacks and react to (academic) challenges [7]. There have been a multitude of studies attempting to explain how beliefs about the malleable (growth) or trait-like (fixed) nature of human intelligence affect students’ learning motivation in educational settings [8,9,10]. A growth mindset about intelligence can substantially support functional learning processes and individuals’ responses to difficulties, enabling the pursuit of long-term educational goals that contribute to academic tenacity among young people [11,12,13]. Those with a fixed mindset regarding their capability may shy away from challenges or fail to reach their full potential. Regardless of the two opposites in mindsets, internal beliefs exist on a spectrum from fixed to growth and can vary in different situations and circumstances [7]. Dweck [3] has stated that differences in mindsets about intelligence do not most likely exist because of differences in the individuals’ actual abilities.

This article investigates how mindset regarding intelligence and giftedness—together with academic achievement and gender—predict educational aspirations. Educational aspirations refer to goals and plans within educational settings.

Ahmavaara and Houston [14] found implicit theories about intelligence related to educational aspirations among British secondary school students. A growth intelligence mindset had a more substantial effect on educational aspirations among those studying in selective schools than in non-selective schools. Students’ achievement aspiration was predicted directly by gender, school type, and intelligence mindset. The type of school indirectly affected aspirations, as it was mediated by perception of one’s intelligence and academic performance. Ahmavaara and Houston (p. 629, [14]) write that the differences between pupils in selective vs. non-selective schools are likely to be a product of the selection process, not a difference in students’ ability.

Glerum et al. [15] studied how the mindset about intelligence differs among students in vocational school and pre-university. Against their proposed hypothesis, hardly any difference was found in students’ mindsets about intelligence between students in different educational tracks that can be seen as selective, thus in the Netherlands, adolescents follow a vocational track, or a secondary education track, based on their level of academic performance in elementary school. In their other study, Glerum et al. [16] studied vocational school students’ intelligence mindset, yet it was not substantially found to differ from students in other forms of education. However, most vocational students did not have a growth mindset, but it seemed that their mindset and academic achievement were unrelated.

After all, the relationship between mindset and educational aspirations is under-researched. Due to the diverse findings, it is relevant to conduct further research on this rather complex topic.

1.1. Mindsets in Education

A growth mindset about intelligence is claimed to form an essential protective factor for academic achievement (e.g., test scores and grades), and students with a growth intelligence mindset commonly outperform students with a fixed mindset when comparing academic achievement [17,18,19,20]. This dissimilarity appears particularly in achievement in mathematics [21,22,23]. A growth mindset is associated with students’ motivation to master tasks and appreciation of schooling. It is shown to associate negatively with students’ fear of failure [24]. Moreover, growth mindset students experience a higher level of engagement toward school [25], and they tend to have finished a higher level of education [12].

Students with a fixed mindset about intelligence show poorer self-efficacy and are more likely to adopt maladaptive strategies for learning [8,26]. A student with a fixed mindset can draw adverse ability inferences about oneself when facing academic challenges or difficulties [19,27]. A fixed intelligence mindset is shown to be more common in students belonging to stereotyped groups, such as people of color and those from families with low socioeconomic status [28]. Claro et al. [29] have written that economic disadvantage can depress students’ academic achievement through multiple mechanisms, including reduced access to educational resources and higher stress levels [30]. A fixed mindset is debilitating (and a growth mindset is more protective) when individuals must overcome significant barriers to success. Separate democratic groups are situated differently in society, and the sense of belonging is not as strong for those from low socioeconomic groups [13,27,31].

A fixed mindset about intelligence can maintain inequality in education and, consequently, in life more broadly. It is also harmful to competent students to attribute success to their talent rather than their effort and learning processes. A growth mindset about intelligence encourages even high-performing students to try harder instead of just trusting their current capabilities [18,32]. A growth mindset has also been recognized to support students during difficult academic transitions, such as moving from elementary to secondary school [12,18,33].

Notwithstanding, some contradictory findings have been produced. Incremental beliefs about intelligence among Greek students did not correspond to school achievement nor support a causal role for implicit beliefs in academic outcomes. Instead, implicit beliefs about intelligence were affected by prior school success and mediated by perceived academic competence [34,35].

1.2. Mindsets about Intelligence and Giftedness

Diverse findings have led researchers to conclude that mindsets could be domain-general or non-specific [36]. Finnish researchers have investigated the constructs of intelligence and giftedness among academically prospering children and adolescents: Kuusisto et al. [32] found that they perceived intelligence and giftedness as two separate domains of talent. Intelligence was perceived as a more malleable quality than giftedness, and boys’ mindsets about giftedness were more fixed compared with girls.

A study among gifted American students found similar results when they contrasted intelligence and giftedness: gifted students perceived giftedness as more fixed than intelligence [37]. Makel et al. [37] state that despite the positive correlation between the natures of intelligence and giftedness, these two constructs cannot be regarded as synonyms. Intelligence and giftedness share intrinsic similarities as constructs, yet they are seen as distinct [32,38,39].

In everyday Finnish language, the word ‘intelligence’ refers to IQ and logical–mathematical and linguistic competence, whereas the word ‘giftedness’ has a broader meaning. Giftedness is said to occur in “all human areas of skills and knowledge,” and it captures all areas of talent (e.g., arts, music, and sports) [40]. Dweck (p. 312, [41]) has suggested that the word ‘gift’ implies that no effort is involved, indicating that giftedness might be seen as more fixed than intelligence. Both constructs are still easily associated with education [42,43,44].

1.3. Educational Aspirations

Educational aspirations predict educational goal selection and the organized pursuit of long-term goal-driven learning activity. These are anchored to students’ self-defining beliefs and are internalized by achieving educational objectives and understanding the connection between self-regulation and later educational attainment [45]. In the long term, educational aspirations are fairly good predictors of academic achievement [46].

Adolescents who set educational goals and aspirations have higher levels of educational attainment [46,47]. Hence, they are more likely to achieve their future occupational goals [48]. During adolescence, educational aspirations become more realistic based on students’ interests, perceived abilities, individual characteristics, and the opportunities available to them [49]. Low academic performance and weak motivation toward learning have been linked with, for example, low educational aspirations, educational delays, and dropout [50,51,52,53,54]. Educational aspirations are used to explain both individuals’ occupational choices and educational disparities in life [55,56].

A Finnish study [57] examined how educational aspirations differ between the genders. It was found that math and reading performance among girls was associated with educational aspirations, but only performance in math was linked to boys’ educational aspirations. High educational aspirations were predicted by positive self-beliefs, study engagement, and lack of school burnout. Another study [50] found that the highest-performing students had the highest educational aspirations (university). In contrast, students with the lowest academic performance had the lowest aspirations (comprehensive school).

Most studies have investigated high or low educational aspirations. However, some adolescents express uncertainty about their aspirations: Students who are still determining what they would like to do regarding their education are those with uncertain aspirations. Uncertainty in educational aspirations may put young people at risk of poor educational and life outcomes [58], and there is a need to investigate uncertain aspirations more in depth. Thus far, studies [58,59] focusing on young people’s uncertain aspirations have found that adolescents with uncertain career ambitions earned significantly less in young adulthood than those with specific professional and non-professional aspirations. Moreover, adolescents from low socioeconomic backgrounds and with low academic achievement were more likely to hold uncertainty in their career aspirations. In the present study, we investigate students’ educational aspirations by focusing on their academic, vocational, and unknown aspirations.

Generally, most young people seem highly aspirational, but they might lack the suitable opportunities and support to unleash their aspirations in formal schooling [60]. The tensions between informal and formal learning practices have increased because of the digital media. Internet nowadays provides informal learning opportunities for those who are willing. Ito and others claim that for an increasing number of young people, education no longer represents the unique place for learning, and the significance of formal educational degrees is no longer bright for all youth [61]. It might be that the educational context is currently failing to support students’ skills, self-concepts, and capabilities well enough—especially during adolescence, which is a risk of difficulty for some [45].

1.4. The Finnish Context

Finland’s public schooling has maintained a good reputation by international standards, and the country is known for having created a top-performing comprehensive education system with highly educated class and subject teachers. Finnish education aims to promote academic performance while creating inclusive learning environments with no ability grouping.

In recent years, however, national and international evaluations have indicated a continuing decline in the learning outcomes of Finnish students completing basic education [62]. Academic achievement has worrisomely declined among boys [63]: in secondary education, boys generally perform worse than girls [24,64,65]. The national assessment of ninth graders showed that girls outperformed boys in every area studied: reasoning skills, mathematical thinking, and reading comprehension [64]. In 2018, the Finnish National Board of Education launched a pilot project called Boys’ Learning Challenges and Solutions [63], which aims to find ways to improve boys’ learning outcomes by 2025. Regarding gender and educational choices, in 2016, 63 percent of girls who finished elementary school applied primarily to upper secondary school, and 55 percent of boys applied primarily to vocational education [63]. These statistics indicate the burgeoning trend of boys increasingly gravitating toward shorter educational tracks, and boys seem to have stronger motivation towards studying in vocational schools. Boys’ engagement even seems to increase when they begin their studies in vocational school after lower secondary school [66].

Additionally, there is an increasing lack of school motivation, particularly among adolescents with immigrant or low socioeconomic backgrounds [67], along with those who are active sociodigital participators [68].

Nowadays, the regional differences in schools’ academic performance are starting to point toward an increase in the family-background effect. A concern has been raised about school diversification in learning outcomes and urban segregation [69,70]. When students’ well-being is observed, girls are more likely to suffer from exhaustion or feelings of inadequacy [66] and boys from cynicism [51,71]. The latest OECD report stirred up a worried debate regarding the matter’s state of education and its future: the educational attainment of young people of working age in Finland is well below the average of other OECD countries [72]. The proportion of Finnish people aged 25 to 34 with higher education has remained at 40 percent for years. Meanwhile, across the OECD countries, the proportion of higher education students in the same age group has risen from 27 percent to 48 percent [72].

In the fall of 2021, the Finnish government elected to raise the comprehensive school age. From the previous 16, the age was adjusted to 18. Currently, comprehensive education includes elementary school (grades 1 to 6), lower secondary school (grades 7 to 9), and three years in upper secondary education (either upper secondary school or vocational education). The remarkable amendment aims to raise the level of education among the Finnish population and to support the increasing dropout rates among youth and the observed decline in study motivation.

During the data collection, however, comprehensive education continued until age 16, including only years in elementary school (grades 1 to 6) and lower secondary school (grades 7 to 9). In practice, it means that participants of this study could continue studying in upper secondary school, a vocational institute or leave education.

When continuing to upper secondary education, study places are granted based on the grades in the ninth-grade student diplomas. Gaining entry to some of the highest-performing upper secondary schools is today highly competitive, and not everyone can be admitted to their first choice of school or commuter school. More often, those with lower grades on their diploma apply to vocational education.

After upper secondary education, it is possible to apply to higher education, which consists of two parallel tracks: universities or universities of applied sciences (UAS). Admission is either based on the diploma from upper secondary education or the entrance examination. University is typically perceived as an institution for those obtaining the highest achievement in the matriculation examination that conclude upper secondary school. In recent years, the role of mathematics has become significant when applying to the university; applicants who apply straight after upper secondary school gain the highest points in the selection process if they have done well in the matriculation exam in mathematics.

The applicant’s previous academic success and home background (education and socio-economic status) are strongly linked to whether the applicant aspires to the vocational or academic higher education sector. Stenström et al. [73] found that students are more likely to apply for vocational studies if their parents have a degree in vocational education. Moreover, students who have faced problems in education are probably more likely to apply to vocational educational tracks [16], as their unpleasant educational experiences may lead to the development of a fixed mindset among these students [9]. However, accessing some highly valued vocational tracks (i.e., arts, music, business economy) can be challenging. Vuorinen and Valkonen [74] found that the labor market valued university degrees slightly higher than UAS degrees, which can fuel dispensable competition between these higher education institutions.

2. The Present Study

Our aim was to investigate how mindsets, academic achievement, and gender predict educational aspirations in the eighth grade. To our knowledge, only a few studies have previously investigated the relationship between students’ mindsets about intelligence and educational aspirations [14,15,16] with varying results.

This current research extends this line of inquiry to the Finnish educational context, asking the following question: How do mindsets about intelligence and giftedness, academic achievement in math and reading, and gender predict educational aspiration among eighth-grade students in Finland?

The participating students at the time of the data collection were 14 years old, studying the penultimate year of compulsory education. They were about to face the most critical decisions regarding their future education and occupation, as they needed to decide if they were applying to upper secondary education. Moreover, it is common to prefigure life after upper secondary education. The scholarly path in formal education affects adolescent life and the future.

The eighth-grade students in this study likely feel they have more freedom to choose their future than those supervised to upper secondary education after the ninth grade. Nevertheless, even when the comprehensive education continued until age 16, most from the age cohort continued studying for the equivalent of three years in upper secondary school or vocational education, regardless of studying from this point on being voluntary.

Understanding whether and how mindsets about one’s abilities can predict students’ educational aspirations makes it possible for scholars, educators, and counselors to support students toward their educational goals and occupations to fulfill their potential.

We expect students’ mindsets about intelligence and giftedness to predict their educational aspirations. Moreover, it is likely that a growth mindset about intelligence and giftedness indicates students’ academic aspirations; potentially, the fixed mindset in those constructs predicts vocational and unknown aspirations. Domain-specific performance and gender are likely to predict educational aspirations, too. Boys might show stronger intentions toward vocational education than girls and non-binary individuals.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Procedure and Participants

The data for this cross-sectional study were collected from 30 schools in the fall of 2020 in Helsinki, Finland. Data were collected via an online questionnaire surveying mindsets and academic aspirations. Respondents’ academic grades were requested from the education division of Helsinki. The education division holds a databank of each school’s educational evaluation, i.e., every student’s school reports from each academic year. Current school reports include grades from the academic year 2020–2021.

The online questionnaire was administered within regular school hours. Before completing the questionnaire, respondents were explained voluntary participation, a guarantee of total anonymity, and a reminder of their right to withdraw from the research at any time.

The respondents (N = 1136) were 14 years old. Approximately half (n = 580, 51.6%) identified themselves as girls, almost half as boys (n = 520, 45.7%), and a small minority as non-binary (n = 36, 3.1%). Six participants did not report their gender; thus, they were excluded from this study.

The survey was provided in the two official languages, Finnish and Swedish, as well as in English. The majority (96.1%) of the participants responded to the survey in Finnish. The students and their guardians were asked to consent to participate in this study. Ethical approval for this research was obtained from the University of Helsinki’s Research Ethics Committee and the Education Division of Helsinki.

3.2. Measurements

To measure students’ beliefs regarding the malleable or static nature of intelligence and giftedness, Dweck’s Implicit Theory of Intelligence [3] scale was utilized with three fixed mindset items. Respondents indicated on a scale of 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (strongly disagree) the extent to which they endorsed each of three statements: “People have a certain amount of intelligence, and not much can be done to change it”, “To be honest, you can’t really change how intelligent you are”, and “People can learn new things, but cannot really change their basic intelligence”. To measure giftedness, we adapted the instrument by replacing the word “intelligence” with “giftedness”.

Educational aspirations were examined using a six-point Likert scale with the statement: “What is the highest degree of education you think you will accomplish?” Response options were: 1 = Basic education, 2 = High school, 3 = Vocational school, 4 = University of Applied Sciences, 5 = University, and 6 = I do not know. The distribution of responses to the six categories was uneven, as a vocational school and basic education had the lowest responses. Instead of using all six categories, we formulated three categories with a reasonably even number of responses. The university was chosen to represent the category of academic aspirations. The University of Applied Sciences, upper secondary school, vocational school, and basic education were chosen to represent vocational aspirations. “I do not know” responses represent the category of unknown aspirations.

The academic grades in math and reading used in the present study are based on teachers’ evaluations of each student. Grades at Finnish schools are not based on standardized tests; instead, they are composed of each student’s effort and classroom participation, test performance, and homework activities. Grades range from 4 (the lowest) to 10 (the highest).

3.3. Data Preparation

We started by reverse coding the Implicit Theory of Intelligence scale so that higher scores indicate a growth mindset. Cronbach’s Alpha value for intelligence was α = 0.87, and for giftedness, α = 0.92.

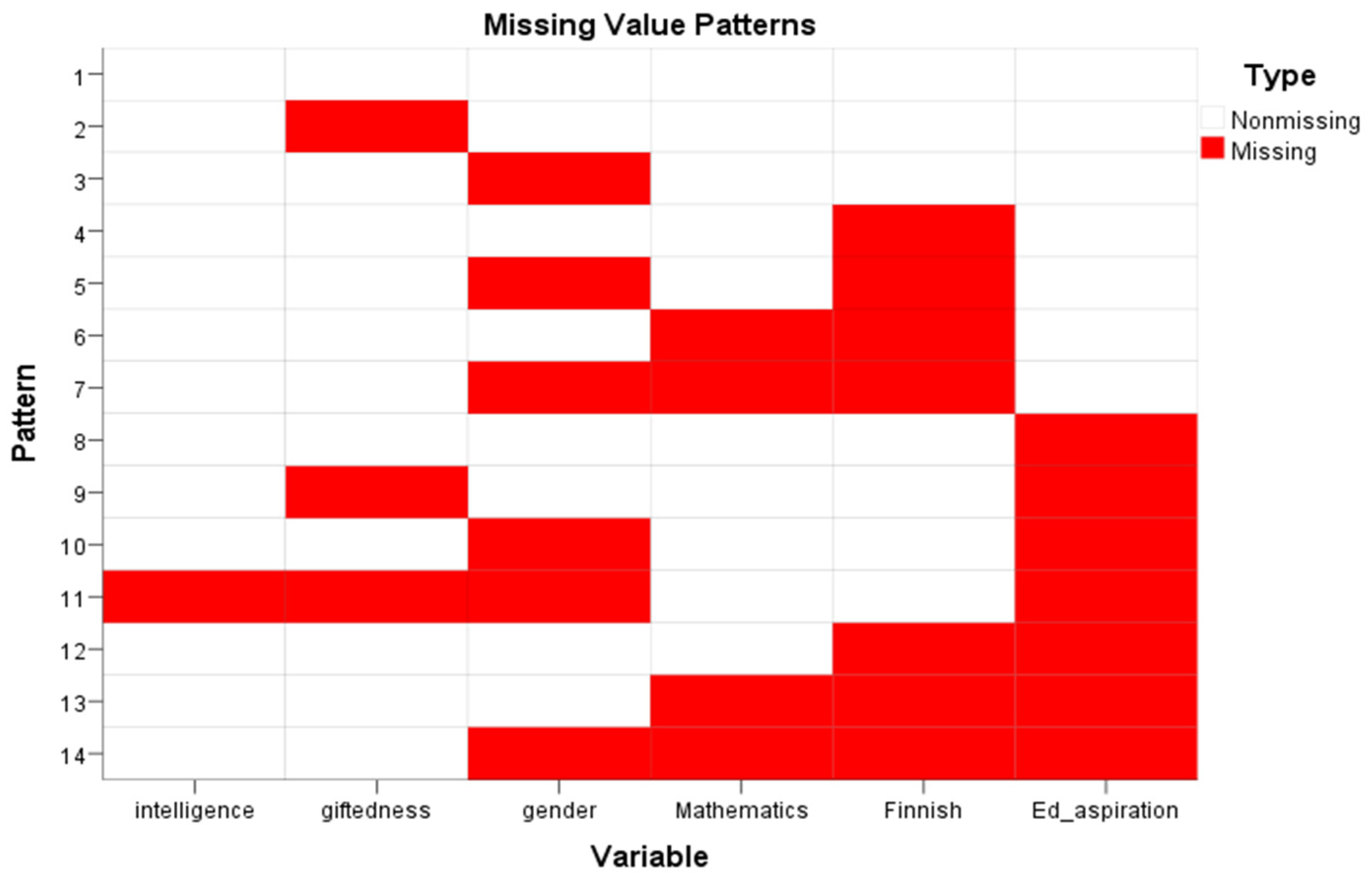

The missing value analyses revealed that most of the values were scattered across academic achievement and educational aspirations. The grades in mathematics (11% of cases) and reading (16.3% of cases) included a significant number of missing values, as there was missing information in the dataset: half of the grades from one school and all from another were lacking. Despite this unfortunate occurrence, we concluded it was feasible to use the achievement data in the predictive analysis.

In educational aspiration, there were missing values in 28.6% of cases. The principal question was whether the missing values were a random process or a systematic bias. The missing values were inspected using Little’s MCAR test. As a result, the assumption that values are missing completely at random was rejected (Chi-Square = 57,849, DF = 35, p < 0.05). The procedures for dealing with the missing data depend on the nature of the data [75,76]. Because of the systematic bias in the missing values of the main variables, multiple imputation was used. Before performing imputation, we analyzed the pattern of the main variables. Since the missing data were found to have a scattered pattern toward a few variables, particularly educational aspirations, we used the monotone method (10 iterations) to impute data. All variables in the dataset (mindsets about intelligence and giftedness, educational aspirations, achievement in mathematics and reading, and gender) were included for imputation, and five imputations were created. Thus, for data analysis, SPSS provided us with five sets of analysis separately and a pooled analysis combined with all five results, which is used for reporting the results.

Multiple imputation restores the natural variability of the missing values while incorporating the uncertainty due to the missing data, which results in a valid statistical inference. It is robust to the violation of the normality assumptions and produces appropriate results even in small sample sizes or a high number of missing data [77]. When using multiple imputation, each missing data point was replaced with a set of m > 1 plausible values to generate a more complete dataset [78]. Missing values were predicted by using the existing data from other variables and then replacing the missing values with the predicted values, creating imputed data. The missing value patterns can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The pattern of missing values in the data.

3.4. Data Analysis Strategy

Given the nested data structure, all variables were first standardized to be in the same metric. Before further analyses, we investigated whether the constructs of intelligence and giftedness differ. Building on the findings of Kuusisto et al. [32], we formulated the standpoint for the present study and decided to investigate intelligence and giftedness as separate constructs of mindset among a larger sample of students. Results from a confirmatory-factor analysis confirm intelligence and giftedness to be separate constructs, as per Table 1.

Table 1.

CFA for one- and two-factor solutions of mindset.

We began the primary analysis by examining zero-order correlations between mindsets, academic achievement, and educational aspirations. To investigate how intelligence and giftedness mindsets, academic achievement in math and reading, and gender predict educational aspirations, we used a multilevel multinomial logistic regression analysis with SPSS Statistics 26.

Educational aspirations were used as a dependent variable with three levels (academic aspiration, vocational aspiration, and unknown aspiration), while intelligence and giftedness mindsets, academic achievement, and gender were used as independent variables.

In multinomial logistic regression, the odds ratio or Exp (B) coefficients are mainly used to predict how independent variables fall into the dependent variable categories. An odds ratio of <1 shows that the outcome is more likely to be in the reference group (in this case, academic aspiration). An odds ratio of >1 indicates that the outcome is more likely to be in the comparison groups (vocational or unknown educational aspiration) [79].

Additionally, we examined how predicting variables were distributed across the academic aspiration with a one-way ANOVA. For example, whether students with the highest scores in mindsets mainly chose academic aspirations or other categories. The final statistical test was a chi-square test to examine the gender distribution of academic aspirations.

4. Results

4.1. Zero-Order Correlation of Main Variables

Inspection of Table 2 shows that educational aspirations positively correlated with math and reading achievement and negatively correlated with the mindset about intelligence and giftedness. In other words, students with higher scores in math and Finnish are more likely to choose the university as their educational aspiration. Based on an article by Funder and Ozer [80] the effect size for reading achievement and educational aspirations is large and medium for math achievement and educational aspirations. The effect size for the negative correlation between the mindset about intelligence and educational aspirations is small and very small for the negative correlations between mindset about giftedness.

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations of the main variables in the study.

4.2. Predicting Educational Aspirations with Independent Variables

To examine the extent to which mindsets about intelligence and giftedness, academic achievement in math and reading, and gender predict academic aspirations, we conducted the following steps:

Step 1: Building an empty model. To understand to what extent the log-odds of students’ educational aspirations vary between schools, we performed an intercept-only model with no predictors to estimate the log-odds of choosing vocational or unknown educational aspirations across all schools. The model included the three dependent variables (academic, vocational, and unknown aspirations, with the academic variable being the reference category) and school ID as the second level of data (schools pertain to a level rather than a predictor variable). Considering the fixed coefficients, the odds ratio for unknown educational aspiration (B = −0.82, ExpB = 0.44, p < 0.05) and vocational educational aspiration (B = −0.57, ExpB = 0.56, p < 0.05) were statistically significant. It is less likely for a respondent to fall into the categories of unknown or vocational aspiration relative to academic aspiration, with the odds ratio being smaller than 1. The z-test examined whether the log-odds may vary from one school to another. The results indicate that students from some schools are more likely to choose a vocational education (z = 2.64, p < 0.05). No statistically significant differences were found in choosing unknown educational aspirations (z = 1.75, p > 0.05). Results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Effects for the log-odds of educational aspiration in different schools.

Step 2: A model with the first-level predictors. A model with five predicting variables (mindset about intelligence, mindset about giftedness, academic achievement in math, academic achievement in Finnish, and gender) was used from the first level (students) to investigate the effect of a relevant first-level variable that varies between clusters. We did not have particular variables in the second level.

First, mindsets about intelligence and giftedness were analyzed for the similarity of the two constructs that could cause issues with multi-collinearity. The t-test (Table 4) showed that considering the coefficients, only the mindset about giftedness predicted the unknown aspiration (t = 2.11, p < 0.05). Based on the odds ratio for the variable (1.086), students are more likely to fall into the category of an unknown aspiration than an academic aspiration. Nevertheless, the effect was not statistically dependent on the school level (z = 1.76, p > 0.078), as it does not make a statistical difference across all schools. The z-test (z = 2.64, p < 0.05) was statistically significant in the observation of the vocational aspiration: in choosing a particular educational aspiration, the effects of mindset about intelligence differed from one school to another. However, the fixed effects for mindset about intelligence (t = −0.003, p > 0.05) and giftedness (t = 1.10, p > 0.05) were statistically insignificant. When the effects of intelligence and giftedness mindset on educational aspiration in different schools were examined separately, the results show that only giftedness mindset predicts unknown educational aspiration. Still, such an effect is not dependent on the school level. The investigation of the interaction term of intelligence and giftedness showed that the variables significantly predicted how to choose vocational aspiration (B = −0.062, ExpB = 0.94, p < 0.05). The result indicates that the higher the interaction terms of intelligence and giftedness mindset, the less likely the students are to choose vocational aspiration than academic one. The interaction term for unknown aspiration was not statistically significant (B = 0.015, ExpB = 1.01, p > 0.05). The z-tests for vocational aspiration were statistically significant (z = 2.67, p < 0.05), indicating that choosing vocational aspiration considering the effect of interaction terms of intelligence and giftedness was different from one school to others.

Table 4.

The effects of mindset on educational aspiration in different schools.

Step 3: Running a final model. The last analysis of the model with first-level predicting variables was to include all five predicting variables in the first level to see whether the model improved. The results from these analyses are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Fixed effects of mindset on educational aspiration in different schools.

As per Table 5, academic achievement in math (t = −2.36, p < 0.05) and mindset about giftedness (t = 2.35, p < 0.05) predict unknown educational aspiration. The chance of choosing an unknown aspiration compared with academic aspiration decreases as the score in math achievement increases (B = −0.10).

The mindset about giftedness showed the opposite effect (B = −0.094), indicating that with an increase in giftedness mindset, the chance of following the unknown educational aspiration increases. The z-test (z = 1.35, p > 0.05) revealed that the effect of mindset about giftedness and achievement in math was not statistically different across schools.

Gender significantly affected vocational aspirations (t = 3.74, p < 0.01), as results indicate boys prefer vocational aspiration to academic aspiration, and the z-test (z = 2.52, p < 0.05) revealed that the effect of gender on vocational aspiration statistically differs among schools.

The rest of the variables (mindset about intelligence, achievement in reading, and non-binary gender) did not contribute to the model.

Generally considering the nested structure of data (student’s level 1 and school level 2), the results show that unknown educational aspirations did not statistically differ across schools. Nevertheless, the results indicate a significant difference in vocational aspirations, which varied from one school to another. The first-level predicting variables showed the following results:

- -

- Mindset about giftedness had a positive effect on choosing unknown aspiration compared with academic aspiration.

- -

- The interaction terms of intelligence and giftedness mindset had a negative effect on vocational compared with academic aspiration.

- -

- Achievement in mathematics had a negative effect on unknown aspiration compared with academic aspiration, whereas the mindset about giftedness positively affected the decision.

- -

- Being a boy positively affected choosing vocational aspiration compared with academic aspiration.

4.3. The Distribution of Independent Variables into the Three Educational Aspirations Categories

Lastly, a one-way ANOVA was performed to examine the extent to which the independent variables predicted educational aspirations. That is, to see the distribution of students with different mindsets and degrees of achievement into the three educational aspirations categories.

Students with a growth mindset about intelligence selected vocational aspirations (Table 6). Unknown aspiration in the second place indicates that a group of students with a growth mindset about intelligence has not yet decided about their educational aspirations.

Table 6.

One-way ANOVA for intelligence mindset grouped by academic aspiration.

Students with a growth mindset about giftedness chose unknown and vocational educational aspirations. Conversely, students with a fixed mindset selected academic aspirations (Table 7).

Table 7.

One-way ANOVA for giftedness mindset grouped by academic aspiration.

Students with the highest math grades had academic aspirations, and students with lower grades in math had vocational and unknown aspirations (Table 8).

Table 8.

One-way ANOVA for mathematics achievement, grouped by academic aspiration.

Students with higher grades in reading chose academic aspiration as their first educational aspiration, while students with lower grades in reading selected vocational education as their aspiration.

All of the results from Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 are statistically significant (p < 0.001), which shows that the null hypothesis is rejected for all independent factors.

Table 9.

One-way ANOVA for achievement in reading, grouped by academic aspiration.

Table 10 shows that 53.1% of girls, 48.7% of boys, and 50% of non-binary chose academic aspiration; 23.8% of girls, 48.7% of boys, and 22.2% of non-binary chose vocational aspirations; and 23.1% of girls, 19.6 of boys, and 27.8% non-binary chose unknown aspiration. Based on chi-square analysis, the differences were statistically significant (χ2 = 9.92, df = 2, p < 0.05).

Table 10.

Descriptive statistics of educational aspirations grouped by gender.

5. Discussion

The present study investigated how mindsets about intelligence and giftedness, academic achievement, and gender predict academic, vocational, and unknown educational aspirations among eighth-grade students in Finland. The results of the final model show that the growth mindset about giftedness predicted unknown aspirations. The interaction terms of intelligence mindset and giftedness mindset jointly affect choosing academic aspiration. Achievement in mathematics positively related to academic aspiration, whereas the mindset about giftedness positively affected unknown aspirations. Regarding gender differences, boys were more likely to have vocational aspirations than girls and non-binary individuals.

These results only partially support our hypothesis. Contrary to what was expected, students’ mindsets about intelligence did not predict educational aspirations in the model. This aligns with results from a study by Glerum et al. [16], who did not find pre-university students’ or vocational school students’ mindsets to differ, yet, the vocational school students did have a growth mindset in general. The results from Ahmavaara and Houston [14] are different, as they found that intelligence mindset was related to educational aspirations among British secondary school students. Of course, it is crucial to contemplate how the (school) culture influences results. As in the British study, students were from selective vs. non-selective schools, and students with a higher academic performance (selective-school students) also had a growth mindset about intelligence.

Interestingly, the growth mindset about giftedness predicts unknown aspirations but not academic ones, which would seem logical considering the previous mindset research (e.g., [32]). Surprisingly, the growth mindset about intelligence did not contribute to the model, which is contrary to what has been claimed by Dweck [3,81], as it was suggested that the intelligence theory has an effect on aspirations, along with Ahmavaara and Houston [14]. It is significant to contemplate the effect, as the students in the British study by Ahmavaara and Houston were from selective vs. non-selective schools. Students with higher academic performance also had a growth mindset about intelligence. A study among Greek students found that incremental beliefs about intelligence did not correspond to school achievement [34]. However, students’ mindset about intelligence was affected by prior school success and mediated by perceived academic competence.

There can be several explanations for this somewhat anomalous result. It can be speculated whether results indicate that young people whose interests are something other than theoretical subjects, such as mathematics, do not consider studying in the university as attractive to them, as those whose interests are in theoretical subjects. Students who participate in artistic activities outside of school are likely to be more sensitive to the definition of giftedness if their skills and talent is receiving attention there. Students with interests other than in theoretical subjects, for example, arts, do not necessarily view their giftedness as developed at formal institutions or universities; thus, their aspirations are outside the academic institutions.

Additionally, it has been recognized that most young people seem aspirational regarding their future, but in informal schooling, they might lack the suitable opportunities and support to unleash their aspirations [60]. Ito and others have claimed that an increasing number of young people might be fleeing from education as it no longer represents a unique place for learning for them [61]. One explanation might be that the educational context currently fails to support every student’s skills, self-concepts, and capabilities well enough—especially during adolescence [45]. More, young people use the Internet immediately when they have a problem to solve. In contrast, school learning relies too often on encapsulated and outdated textbooks. Moreover, many students solve problems outside school through active exploration, whereas learning by telling still characterizes school learning. Simultaneously, education is considered a place for young people to develop their learning skills and motivation toward learning.

Intelligence and giftedness can be seen as culturally associated with traditional forms of academic achievement [82]; thus, they may be culturally mediated constructions [83]. Mindsets likely reflect the dominant social representations of culture, school, and home [84]. However, the implicit theories of intelligence and giftedness seem to exist in individual minds. Overall, the results in this study emphasize that the practices of schools can unintentionally socialize students towards the ideas and ideals of what constitutes a “good student” for academic studies or what is suitable for a student in the vocational track. Current institutional evaluation practices can shape perceptions about good students and their abilities and capabilities [85]. Despite the inclusive ethos of the Finnish comprehensive school, implicitly categorizing students based on their academic achievement makes the theories of both intelligence and giftedness more explicit [82,86]. Additional research is needed to illuminate the relationship between students’ mindsets and their educational aspirations.

It was not unexpected that academic achievement—especially in mathematics—predicted a motivation toward academic studies, supported in several studies, also among Finnish students [50]. Ninth graders’ math performance seemed to be significantly linked to the level of educational and occupational aspirations in general; the highest-performing students had the highest educational aspirations (university), with the distinction that among boys, only math performance was linked to their aspirations [50]. In the same study, students’ high achievement in reading predicted academic aspirations. In our model, achievement in the reading did not predict educational aspirations. In a study by Kuusisto et al. [32], the giftedness mindset supported higher mathematics grades among students in the 7th grade. The application to higher education emphasizes mathematics, so it has become more critical for applicants. This might even highlight how achievement in math predicts higher educational aspirations.

We found gender predicted educational aspirations, so that boys were more likely to set themselves vocational aspirations. Girls, on the other hand, were more likely to have academic aspirations. The result regarding boys’ vocational aspiration is expected when considering what is known about the development of Finnish boys’ educational tracks. Finnish boys tend to follow lower educational tracks more often than girls do [52]. Moreover, boys are found to be more cynical toward school and education, at least at the upper secondary level of education. It has been observed that boys’ study engagement increases when they enter vocational school after lower secondary education [66]. One possible explanation for this is that Finnish boys are suffering from a lack of interest in reading, which is necessary for academic studies [24,65,87].

In a study by Hansen et al. [88], they stated, “In Finland, there are no school differences; instead, very substantial classroom differences have been identified”. Surprisingly, oppositely to what was expected, the model revealed differences between schools in selecting educational aspirations: selecting academic aspirations compared with vocational aspirations was found to differentiate between schools inside Helsinki. This indicates that the concern about school diversification in learning outcomes and possible segregation can affect students’ aspirations [69,70]. However, there were no differences between selecting the unknown aspiration and academic aspiration.

When considering the correlations and one-way ANOVA, we found some contradictions compared with the multilevel multinomial logistic regression model. The growth mindset about giftedness contributed to unknown aspirations, supporting the main model’s results. The growth mindset about giftedness also contributed to vocational aspiration in one-way ANOVA but did not contribute to academic aspiration.

One-way ANOVA showed that the growth mindset about intelligence contributed to students’ vocational aspirations, and the fixed intelligence mindset contributed to academic aspirations, as did the fixed mindset about giftedness. These results raise questions rather than answer questions, which raises an urge to further study the mindsets about intelligence and giftedness in the Finnish context—especially among lower secondary students.

Because the growth mindset about intelligence is claimed to form an essential protective factor for learning motivation and students’ academic achievement, investigations regarding the constructs of intelligence and giftedness, gathering data, and presenting results from versatile schools and students are critical. In the study by Kuusisto et al. [32], their students represented at some level the top of Finnish academically oriented students, as the study was carried out in a Teacher Training School at the University of Helsinki, which commonly has high-performing students. Participants in our study are from schools all over the city of Helsinki.

When investigating mindset, it is essential to reflect on how mindset was assessed. In our survey, a scale with fixed mindset items was used. We chose to present only the entity items due to previous research in the intelligence domain [89] showing that when both entity and incremental options are included, it is common to endorse incremental statements wildly when contrasting statements are presented. Leggett [89] argued that incremental belief might be pretty compelling and may be the more socially desirable choice. Ultimately, however, as Yeager and Dweck [8] have highlighted, “mindsets are not all-or-nothing, but conceptualized as being on a continuum from fixed to growth”.

6. Conclusions

Our findings challenge how mindset about intelligence has been hypothesized to support students’ educational aspirations. Moreover, it challenges how the mindset about giftedness has been found to support student’s academic aspirations. However, further international and cross-cultural research is required to clarify the differences between our results and those of previous research.

Homogenous schools have been the pride of Finnish education for decades. Based on our results, there are differences between schools, and the difference affects students’ educational aspirations. These indicators are worrisome and imply increasing segregation inside Helsinki between the schools and residential areas.

This study is one step forward in demonstrating and understanding the complexity of mindsets and educational aspirations. There is a need to examine further the reciprocal interactive processes between mindsets and those related to educational aspirations.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, J.L. and K.G.; investigation, J.L.; methodology, J.L., K.G. and K.T.; project administration, J.L.; software, K.G.; supervision, K.T. and K.H.; writing—original draft, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is part of research project Growing Mind: Educational transformations for facilitating sustainable personal, social, and institutional renewal in the digital age. Within the Growing Mind research project, studies have been conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research project have received ethical approval from the University of Helsinki Ethical review board in humanities and social and behavioral sciences.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study will be made available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the restrictions of participant privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dweck, C.S. The Development of Ability Conceptions. In Development of Achievement Motivation; Wigfield, A., Eccles, J.S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-08-049112-7. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. Chapter 4—The Development of Competence Beliefs, Expectancies for Success, and Achievement Values from Childhood through Adolescence. In Development of Achievement Motivation; Wigfield, A., Eccles, J.S., Eds.; Educational Psychology; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 91–120. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S. Self-Theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-315-78304-8. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S. Implicit Theories as Organizers of Goals and Behavior. In The Psychology of Action: Linking Cognition and Motivation to Behavior; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 69–90. ISBN 978-1-57230-032-3. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S.; Chiu, C.Y.; Hong, Y.Y. Implicit Theories and Their Role in Judgments and Reactions: A World from Two Perspectives. Psychol. Inq. 1995, 6, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, 2nd ed.; Random House Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager, D.S.; Dweck, C.S. What Can Be Learned from Growth Mindset Controversies? Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeager, D.S.; Dweck, C.S. Mindsets That Promote Resilience: When Students Believe That Personal Characteristics Can Be Developed. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 47, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattan, A.; Good, C.; Dweck, C.S. “It’s Ok—Not Everyone Can Be Good at Math”: Instructors with an Entity Theory Comfort (and Demotivate) Students. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, R.W.; Pals, J.L. Implicit Self-Theories in the Academic Domain: Implications for Goal Orientation, Attributions, Affect, and Self-Esteem Change. Self Identity 2002, 1, 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, J.; Fried, C.B.; Good, C. Reducing the Effects of Stereotype Threat on African American College Students by Shaping Theories of Intelligence. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 38, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D.S.; Hanselman, P.; Walton, G.; Rege, M.; Solli, I.F.; Ludvigsen, S.; Bettinger, E.; Hooper, S.Y.; Hinojosa, C.; Tipton, E.; et al. How Can We Inspire Nations of Learners? Evidence from Growth Mindset Interventions Conducted in Two Countries. Am. Psychol. 2018, 76, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S.; Walton, G.M.; Cohen, G.L. Academic Tenacity: Mindsets and Skills That Promote Long-Term Learning; Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: Seattle, WA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmavaara, A.; Houston, D.M. The Effects of Selective Schooling and Self-Concept on Adolescents’ Academic Aspiration: An Examination of Dweck’s Self-Theory. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 77, 613–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glerum, J.; Dimeska, A.; Loyens, S.M.M.; Rikers, R.M.J.P. Does Level of Education Influence the Development of Adolescents’ Mindsets? Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glerum, J.; Loyens, S.M.M.; Rikers, R.M.J.P. Mind Your Mindset. An Empirical Study of Mindset in Secondary Vocational Education and Training. Educ. Stud. 2019, 46, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J.L.; Russell, M.V.; Hoyt, C.L.; Orvidas, K.; Widman, L. An Online Growth Mindset Intervention in a Sample of Rural Adolescent Girls. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 88, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, L.S.; Trzesniewski, K.H.; Dweck, C.S. Implicit Theories of Intelligence Predict Achievement across an Adolescent Transition: A Longitudinal Study and an Intervention. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunesku, D.; Walton, G.M.; Romero, C.; Smith, E.N.; Yeager, D.S.; Dweck, C.S. Mind-Set Interventions Are a Scalable Treatment for Academic Underachievement. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.; Master, A.; Paunesku, D.; Dweck, C.S.; Gross, J.J. Academic and Emotional Functioning in Middle School: The Role of Implicit Theories. Emotion 2014, 14, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettinger, E.; Ludvigsen, S.; Rege, M.; Solli, I.F.; Yeager, D. Increasing Perseverance in Math: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Norway. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2018, 146, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaler, J. Developing Mathematical Mindsets: The Need to Interact with Numbers Flexibly and Conceptually. Am. Educ. 2019, 4, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Boaler, J.; Wiliam, D.; Brown, M. Students’ Experiences of Ability Grouping: Disaffection, Polarisation and the Construction of Failure. Curric. Pedagog. Incl. Educ. Values Pract. 2013, 26, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. PISA 2018 Results (Volume III) What School Life Means for Students’ Lives; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.J. Implicit Theories about Intelligence and Growth (Personal Best) Goals: Exploring Reciprocal Relationships. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 85, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimovitz, K.; Wormington, S.V.; Corpus, J.H. Dangerous Mindsets: How Beliefs about Intelligence Predict Motivational Change. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2011, 21, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D.S.; Hanselman, P.; Walton, G.M.; Murray, J.S.; Crosnoe, R.; Muller, C.; Tipton, E.; Schneider, B.; Hulleman, C.S.; Hinojosa, C.P.; et al. A National Experiment Reveals Where a Growth Mindset Improves Achievement. Nature 2019, 573, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Castella, K.; Byrne, D. My Intelligence May Be More Malleable than Yours: The Revised Implicit Theories of Intelligence (Self-Theory) Scale Is a Better Predictor of Achievement, Motivation, and Student Disengagement. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2015, 30, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro, S.; Paunesku, D.; Dweck, C.S. Growth Mindset Tempers the Effects of Poverty on Academic Achievement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 8664–8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, J.D.; Rock, D.A. Academic Success among Students at Risk for School Failure. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, G.L.; Garcia, J.; Apfel, N.; Master, A. Reducing the Racial Achievement Gap: A Social-Psychological Intervention. Science 2006, 313, 1307–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuusisto, E.; Laine, S.; Tirri, K. How Do School Children and Adolescents Perceive the Nature of Talent Development? A Case Study from Finland. Educ. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4162957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D.S.; Kamentz, D.; Urstein, R.; Dweck, C.S.; Brady, S.T.; Keane, L.; Akcinar, E.N.; Gomez, E.M.; Paunesku, D.; Duckworth, A.L.; et al. Teaching a Lay Theory before College Narrows Achievement Gaps at Scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E3341–E3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leondari, A.; Gialamas, V. Implicit Theories, Goal Orientations, and Perceived Competence: Impact on Students’ Achievement Behavior. Psychol. Sch. 2002, 39, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonida, E.; Kiosseoglou, G.; Leondari, A. Implicit Theories of Intelligence, Perceived Academic Competence, and School Achievement: Testing Alternative Models. Am. J. Psychol. 2006, 119, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Hau, K.-T. Are Intelligence and Personality Changeable? Generality of Chinese Students’ Beliefs across Various Personal Attributes and Age Groups. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 34, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makel, M.C.; Snyder, K.E.; Thomas, C.; Malone, P.S.; Putallaz, M. Gifted Students’ Implicit Beliefs About Intelligence and Giftedness. Gift. Child Q. 2015, 59, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusisto, E.; Laine, S.; Rissanen, I. Education of the Gifted and Talented in Finland; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 195–216. ISBN 978-90-04-46500-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, S.B.; Sternberg, R.J. Conceptions of Giftedness; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Laine, S.; Kuusisto, E.; Tirri, K. Finnish Teachers’ Conceptions of Giftedness. J. Educ. Gift. 2016, 39, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S. Self-Theories and Lessons for Giftedness: A Reflective Conversation. In The Routledge International Companion to Gifted Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-203-60938-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. x, 292. ISBN 978-0-465-02610-4. [Google Scholar]

- Räty, H.; Snellman, L. Social Representations of Educability. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 1998, 1, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kuusisto, E.; Tirri, K. How Do Students’ Mindsets in Learning Reflect Their Cultural Values and Predict Academic Achievement? Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2019, 18, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.; Midgley, C.; Wigfield, A.; Buchanan, C.; Reuman, D.; Flanagan, C.; Mac Iver, D. Development During Adolescence: The Impact of Stage-Environment Fit on Young Adolescents’ Experiences in Schools and in Families. Am. Psychol. 1993, 48, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, S.J.; Crockett, L.J. Adolescents’ Occupational and Educational Aspirations and Expectations: Links to High School Activities and Adult Educational Attainment. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 46, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Eccles, J. Who Lower Their Aspirations? The Development and Protective Factors of College-Associated Career Aspirations in Adolescence. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 116, 103367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, I.; Polek, E. Teenage Career Aspirations and Adult Career Attainment: The Role of Gender, Social Background and General Cognitive Ability. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2011, 35, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, L.S. Circumscription and Compromise: A Developmental Theory of Occupational Aspirations. J. Couns. Psychol. 1981, 28, 545–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widlund, A.; Tuominen, H.; Korhonen, J. Academic Well-Being, Mathematics Performance, and Educational Aspirations in Lower Secondary Education: Changes within a School Year. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bask, M.; Salmela-Aro, K. Burned out to Drop out: Exploring the Relationship between School Burnout and School Dropout. Eur. J Psychol. Educ. 2013, 28, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen-Soini, H.; Salmela-Aro, K. Schoolwork Engagement and Burnout among Finnish High School Students and Young Adults: Profiles, Progressions, and Educational Outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Tapola, A.; Linnanmäki, K.; Aunio, P. Gendered Pathways to Educational Aspirations: The Role of Academic Self-Concept, School Burnout, Achievement and Interest in Mathematics and Reading. Learn. Instr. 2016, 46, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorilli, C.; De Stasio, S.; Di Chiacchio, C.; Pepe, A.; Salmela-Aro, K. School Burnout, Depressive Symptoms and Engagement: Their Combined Effect on Student Achievement. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 84, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.; Midgley, C. The Effect of Achievement Goals: Does Level of Perceived Academic Competence Make a Difference? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 1997, 22, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watt, H.M.G.; Eccles, J.S. (Eds.) Gender and Occupational Outcomes: Longitudinal Assessment of Individual, Social, and Cultural Influences; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-4338-0310-9. [Google Scholar]

- Widlund, A.; Tuominen, H.; Tapola, A.; Korhonen, J. Gendered Pathways from Academic Performance, Motivational Beliefs, and School Burnout to Adolescents’ Educational and Occupational Aspirations. Learn. Instr. 2020, 66, 101299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, L.; Schoon, I.; Sabates, R. Uncertain Aspirations for Continuing in Education: Antecedents and Associated Outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 48, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staff, J.; Harris, A.; Sabates, R.; Briddell, L. Uncertainty in Early Occupational Aspirations: Role Exploration or Aimlessness. Soc. Forces Sci. Medium Soc. Study Interpret. 2010, 89, 659–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.; Baird, J.-A. Aspirations and an Austerity State: Young People’s Hopes and Goals for the Future. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2013, 11, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Gutiérrez, K.D.; Livingstone, S.; Penuel, W.R.; Rhodes, J.; Salen, K.; Schor, J.; Sefton-Green, J.; Watkins, C. Connected Learning: An Agenda for Research and Design; The Digital Media and Learning Research Hub Reports on Connected Learning; DML Hub: Irvine, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tulevaisuuden Peruskoulu Future of the Comprehensive School; Opetus-ja Kulttuuriministeriö; Ministry of Education and Culture: Helsinki, Finland, 2015.

- Finnish Agency for Education. Poikien Oppimishaasteet ja-Ratkaisut Vuoteen 2025; Finnish Agency for Education: Helsinki, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hautamäki, J.; Kupiainen, S.; Marjanen, J.; Vainikainen, M.-P.; Hotulainen, R. Oppimaan Oppiminen Peruskoulun Päättövaiheessa: Tilanne Vuonna 2012 ja Muutos Vuodesta 2001 [Learning to Learn at the End of Basic Education: The Situation in 2012 and the Change from 2001]; University of Helsinki: Finland, Helsinki, 2013; pp. 3–122. [Google Scholar]

- Hautamäki, J.; Kupiainen, S.; Kuusela, J.; Rautapuro, J.; Scheinin, P.; Välijärvi, J. Oppimistulosten Kehitys [Development of the Learning Outcomes]. In Tulevaisuuden Peruskoulu [Future of the Comprehensive School]; Opetus-ja Kulttuuriministeriö [Ministry of Education and Culture]: Helsinki, Finland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Salmela-Aro, K.; Tynkkynen, L. Gendered Pathways in School Burnout among Adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K.; Read, S.; Minkkinen, J.; Kinnunen, J.M.; Rimpelä, A. Immigrant Status, Gender, and School Burnout in Finnish Lower Secondary School Students: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2018, 42, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hietajärvi, L.; Lonka, K.; Hakkarainen, K.; Alho, K.; Salmela-Aro, K. Are Schools Alienating Digitally Engaged Students? Longitudinal Relations between Digital Engagement and School Engagement. Frontline Learn. Res. 2020, 8, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernelius, V.; Vaattovaara, M. Choice and Segregation in the ‘Most Egalitarian’ Schools: Cumulative Decline in Urban Schools and Neighbourhoods of Helsinki, Finland. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 3155–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosunen, S.; Bernelius, V.; Seppä, P.; Porkka, M. School Choice to Lower Secondary Schools and Mechanisms of Segregation in Urban Finland. Urban Educ. 2020, 55, 1461–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K.; Muotka, J.; Alho, K.; Hakkarainen, K.; Lonka, K. School Burnout and Engagement Profiles among Digital Natives in Finland: A Person-Oriented Approach. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 13, 704–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Educationa at Glance 2022. OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stenström, M.-L.; Virolainen, M.; Vuorinen-Lampila, P.; Valkonen, S. (Eds.) Ammatillisen Koulutuksen ja Korkeakoulutuksen Opintourat; Jyväskylän yliopisto, Koulutuksen tutkimuslaitos: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2012; ISBN 978-951-39-4850-4. [Google Scholar]

- Vuorinen, P.; Valkonen, S. Ammattikorkeakoulu ja Yliopisto Yksilöllisten Tavoitteiden Toteuttajina; Jyväskylän yliopisto, Koulutuksen tutkimuslaitos: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2005; pp. 1–145. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnik, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 4th ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J. The Relationship between Corporate Diversification and Corporate Social Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinharay, S.; Stern, H.S.; Russell, D. The Use of Multiple Imputation for the Analysis of Missing Data. Psychol. Methods 2001, 6, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.S.; Freese, J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata, 3rd ed.; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-59718-111-2. [Google Scholar]

- Funder, D.C.; Ozer, D.J. Evaluating Effect Size in Psychological Research: Sense and Nonsense. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 2, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S.; Leggett, E.L. A Social-Cognitive Approach to Motivation and Personality. Psychol. Rev. 1988, 95, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasanen, K. Lasten Kykykäsityksen Koulussa [School Children’s Notions of Ability]. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, D.; Lachicotte, W. Vygotsky, Mead, and the New Sociocultural Studies of Identity. Camb. Companion Vygotsky 2007, 20, 101–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, S.; Marková, I. Presenting Social Representations: A Conversation. Cult. Psychol. 1998, 4, 371–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurell, J.; Seitamaa, A.; Sormunen, K.; Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P.; Korhonen, T.; Hakkarainen, K. A Socio-Cultural Approach to Growth-Mindset Pedagogy: Maker-Pedagogy as a Tool for Developing the Next-Generation Growth Mindset; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 296–312. ISBN 978-90-04-46500-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tuominen-Soini, H.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Niemivirta, M. Achievement Goal Orientations and Subjective Well-Being: A Person-Centred Analysis. Learn. Instr. 2008, 18, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2013: OECD Indicators; Education at a Glance; OECD: Paris, France, 2013; ISBN 978-92-64-20104-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, N.; Jordan, N.C.; Rodrigues, J. Identifying Learning Difficulties with Fractions: A Longitudinal Study of Student Growth from Third through Sixth Grade. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 50, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggett, E.L. Children’s Entity and Incremental Theories of Intelligence: Relationships to Achievement Behaviour. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Eastern Psychological Assocition, Boston, MA, USA, 21–24 March 1985. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).