Between the Lines: An Exploration of Online Academic Help-Seeking and Outsourced Support in Higher Education: Who Seeks Help and Why?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of Academic Support

2.2. Provision of Academic Support

2.3. Academic Help-Seeking

3. Materials and Methods

- What was the pattern of student cohort engagement with Studiosity?

- Why did students engage/not engage with Studiosity (i.e., what can we learn from the questions they ask)?

- What were students’ perceptions of Studiosity?

- What are the implications of student engagement patterns with Studiosity?

3.1. Studiosity Data

3.2. Student Survey

- to remind students about Studiosity and encourage them to use it.

- to find out why they were not using Studiosity.

- to evaluate the service independently of the service provider’s own evaluation.

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Studiosity Data

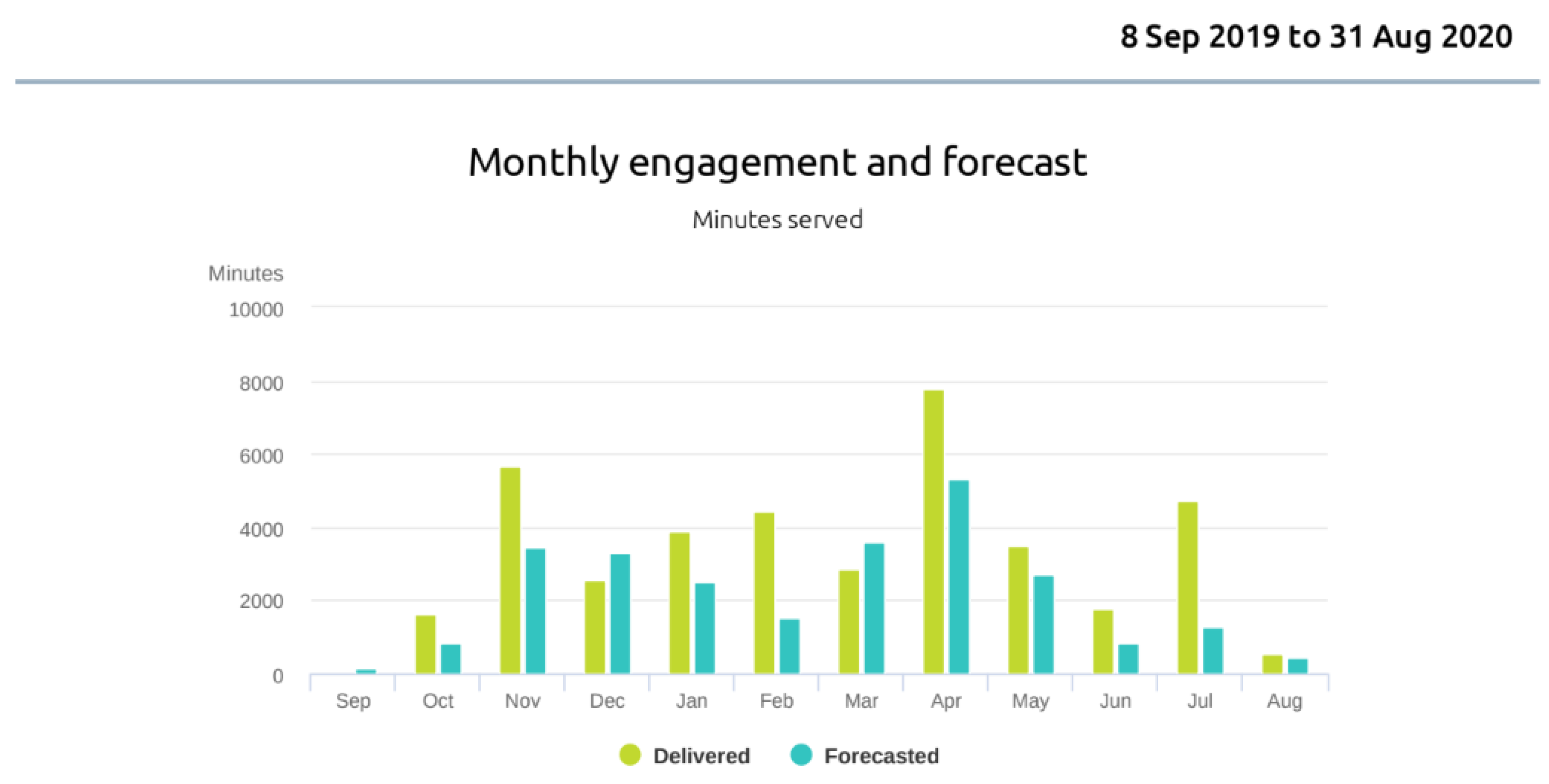

4.1.1. Pattern of Student Cohort Engagement with Studiosity

I am preparing a document longer than the 5k limit. I had put through the first 5k words a few days before. Very little was picked up. I put through the last 5k words this time, (February 2020 PG WF)

I sent one document broken into 5 lots to Studiosity yesterday. (May 2020 PG WF)

I put the document through again and got much more insightful comments from another Reviewer. I am glad I put the work through a second time. this might be harder to do in the university based system? (February 2020 PG WF)

I was interested to see if there was a difference in opinion. (February 2020 PG WF)

I really appreciate you reviewing this—especially as it’s over the holiday period. Thanks so much. (December 2019 WF FY)

4.1.2. Why Did Students Engage/Not Engage with Studiosity?

I found your advice on the conclusion structure a great help for this, and future assignments. Many thanks (February 2020 WF FY)

Always very informative. Very helpful and always seem to learn something new every time I submit a file. February 2020 WF FY)

Hi This is what I have so far Stepsize = Vref/2n = 3.3/2power of 12 = 0.000806 Analogue input/stepsize = 1.65/0.000806 Ans 2047.146 This can not be correct? (May 2019 CL FY)

if a question is asked maybe rather than waiting for the student to answer it (which is impossible as it is themselves who have posed the question, why would you pose a question if you know the answer) maybe answer it. (July 2020 CL SY)

My report organisation and report formatting are less then 60%, ……what can i do to take it to the next level. (December 2019 PG WF)

I am trying to maintain my grade above 70% so any feedback you can offer would be greatly appreciated. (November 2019 WF PG)

I’m unsure at present as it is my first assignment, apologies (November 2019 WF FY)

I am lost in this question and just need to know how to start it (February 2020 CL FY)

Hi lads, can you check spelling, grammar also choice of language please, cheers (November 2019 WF PG)

I have been told by my supervisor that the questionnaire is vague. (April 2019 PG CL)

Hi. I am struggling with writing an academic report…. I would like to get help on how to structure my report and access resources. Thanks

Soooooo much better than having my wife or a friend review my paper (November 2018 FY WF)

It’s been fifteen years since I last wrote an academic essay, this advice is invaluable to me as a learner returning to education (November 2019 WF FY).

I am very unsure about whether this is any good at all! (November 2019 WF FY)

Hi, I have been told I need to provide more critique. Does this refer to:—Finding an alternative academic view on a topic or—Critique from myself, (May 2020 CL FY)

4.1.3. Evaluation of Studiosity

Wow. This is brilliant👏👏👏 I am actually blown away by how intuitive and quick this whole process is for users. Thank you! (October 2019 WF PG)

My issue is with inconsistencies among Studiosity feedback. (May 2020 WF PG)

Session terminated due to network issue at specialist end (May 2020 CL FY)

4.2. Triangulating Usage Data with the Survey

Q4: If you have not used Studiosity, please indicate why not

I have never heard of it before

Not really sure what’s it’s about or how to use it, not promoted or explained well enough

Encourages ill-informed interference with teaching process by commercial agents unscreened by local educational professionals

An aggressive campaign of contact from the Studiosity team

Never having written academic essays before, I really appreciated any assistance that would improve my work. Although our tutors give a broad outline on what is required, they are unable to give feedback on draft essays.

I want to use all tools available to help me improve my grades.

I was curious and in need of an unbiased opinion.

It’s good to get peer review from someone who does not know you and will be impartial

The ‘expert’ had no knowledge of any aspects I asked about. No knowledge about crtical theories and wasted the allocated time asking me stupid questions.

Studiosity adopts a one-fits-all approach to essay writing that is not discipline specific.

Studiosity service is great. It is quick and reliable when it comes to feedback. It gives feedback within 24 hrs. It ensures that the work is academic standard. give honest comment and giving option to go back to correct them before submitting your work.

There was a misconception with tutors that there would be subject advise but Studiosity gave me more confidence that what I was trying to say was being said, rather then being lost in bad writing. It was like a human grammarly and didn’t comment on the subject matter at all. Absolutely fantastic service that I would highly recommend to everyone.

As with all services, the quality of feedback varied depending on who was assessing my work. Some ‘tutors’ were very thorough offering invaluable feedback and suggestions and others were not so good. However on one occasion I submitted the same essay twice which really benefited me.

It is irrelevant, unhelpful and unwelcome, possibly even disruptive of student-teacher relations

I hope [institution] continue to offer students this service as it has not only helped me to improve my work but it has given me more confidence in my own ability. This service is invaluable to “connected”/online students as interaction with our tutors and other students is quite minimal. Also although [institution] does offer the facilities of its writing centre, it’s hours are limited and don’t always suit online students

I am baffled how we are encouraged by the powers that be in [institution] to avail of the service but the tutor doesn’t want it used—for the obvious reason that some of the feedback was total rubbish i.e., in an English lit dissertation feedback I was told to write as if the reader had no knowledge of the novel which is in direct contrast to feedback from tutor.

End the contract

5. Synthesis of Key Findings

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

8. Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morris, N.P.; Ivancheva, M.; Coop, T.; Mogliacci, R.; Swinnerton, B. Negotiating growth of online education in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2020, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinnerton, B.; Ivancheva, M.; Coop, T.; Perrotta, C.; Morris, N.P.; Swartz, R.; Czerniewicz, L.; Cliff, A.; Walji, S. The Unbundled University: Researching emerging models in an unequal landscape. Preliminary findings from fieldwork in South Africa. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Networked Learning 2018, Zagreb, Crotia, 14–16 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bornschlegl, M.; Meldrum, K.; Caltabiano, N.J. Variables related to Academic Help-Seeking Behaviour in Higher Education—Findings from a Multidisciplinary Perspective. Rev. Educ. 2020, 8, 486–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornschlegl, M.; Caltabiano, N.J. Increasing Accessibility to Academic Support in Higher Education for Diverse Student Cohorts. Teach. Learn. Inq. 2022, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.; Mitala, A.; Ratcliff, M.; Yap, A.; Jamaleddine, Z. A public-private partnership to transform online education through high levels of academic student support. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 36, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.; McAuley, A.; Ashton-Hay, S.; van Eyk, T. Just when I needed you most: Establishing on-demand learning support in a regional university. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netanda, R.S.; Mamabolo, J.; Themane, M. Do or die: Student support interventions for the survival of distance education institutions in a competitive higher education system. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, R.; Russell, A.M.T. Stop! Grammar time: University students’ perceptions of the automated feedback program Grammarly. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 35, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador, P.V.; Amador, J.M. Academic Help Seeking: A Framework for Conceptualizing Facebook Use for Higher Education Support. TechTrends 2017, 61, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, H.J.; Harper, R. Developing student writing in higher education: Digital third- party products in distributed learning environments. Teach. High. Educ. 2020, 25, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, J.; Lodge, J. Use of live chat in higher education to support self-regulated help seeking behaviours: A comparison of online and blended learner perspectives. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2021, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenknecht, M.; Hompus, P.; van der Schaaf, M. Feedback seeking behaviour in higher education: The association with students’ goal orientation and deep learning approach, Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambiritch, A. A Social Justice Approach to Providing Academic Writing Support. Educ. Res. Soc. Change 2018, 7, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Xie, Z. Effects of undergraduates’ academic self-efficacy on their academic help-seeking behaviors: The mediating effect of professional commitment and the moderating effect of gender. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2019, 60, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J. Profitable portfolios: Capital that counts in higher education. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2013, 34, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollinger, M.; Cox, S.; Eaton, R.; Vanderlelie, J.; Ridsdale, S. Investigating the Usage and Perceptions of Third-Party Online Learning Support Services for Diverse Students. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2020, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, T.; Muenks, K.; Aguayo, E. “Just Because I am First Gen Doesn’t Mean I’m Not Asking for Help”: A Thematic Analysis of First-Generation College Students’ Academic Help-Seeking Behaviors. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2021, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanagavarapu, P.; Abraham, J. Validating the relationship between beginning students’ transitional challenges, well-being, help-seeking, and their adjustments in an Australian university. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, E.; McCann, J.J.; Haynes, R.; Harland, L. An Exploration of Student Satisfaction Using Photographic Elicitation: Differences between Undergraduate and Postgraduate Students. In Proceedings of the Higher Education Academy Annual Conference: Generation TEF: Teaching in the Spotlight, Manchester, UK, 4–6 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mcpherson, C.; Punch, S.; Graham, E. Transition from Undergraduate to Taught Post Graduate Study: Emotion, Integration and Belonging. J. Perspect. Appl. Acad. Pract. 2017, 5, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.; Johnston, N.; Matthews, S. Online self-access learning support during the COVID-19 pandemic: An Australian University case study. Stud. Self-Access Learn. J. 2020, 11, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.J.; Gonzales, C.; Hill-Troglin Cox, C.; Shinn, H.B. Academic Help-Seeking and Achievement of Postsecondary Students: A Meta-Analytic Investigation. J. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 115, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marineo, F.; Shi, Q. Supporting student success in the frst-year experience: Library instruction in the learning management system. J. Libr. Inf. Serv. Distance Learn. 2019, 13, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.E.O.; Kanchewa, S.S.; Rhodes, J.E.; Gowdy, G.; Stark, A.M.; Horn, J.P.; Parnes, M.; Spencer, R. “I’m having a little struggle with this, can you help me out?”: Examining impacts and processes of a social capital intervention for first-generation college students. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 61, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotar, O. Online student support: A framework for embedding support interventions into the online learning cycle. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2022, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurney, L.; Grossi, V. Performing support in higher education: Negotiating conflicting agendas in academic language and learning advisory work. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2019, 38, 940–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Arbós, S.; Castarlenas, E.; Dueñas, J.-M. Help-Seeking in an Academic Context: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Choi, J. A review of online course dropout research: Implications for practice and future research. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2011, 59, 593–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calarco, J.M. ‘’I Need Help!” Social Class and Children’s Help-Seeking in Elementary School. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 76, 862–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golann, J.W.; Darling-Aduana, J. Toward a multifaceted understanding of Lareau’s “sense of entitlement”: Bridging sociological and psychological constructs. Sociol. Compass 2020, 14, e12798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J. Learning support literacy: Promoting independent learning skills and effective help-seeking behaviours in HE students. J. Acad. Lang. Learn. 2020, 14, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Giblin, J.; Stefaniak, J. Examining decision-making processes and heuristics in academic help-seeking and instructional environments. TechTrends 2021, 65, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winograd, G.; Rust, J.P. Stigma, awareness of support services, and academic help-seeking among historically underrepresented first-year college students. Learn. Assist. Rev. (TLAR) 2014, 19, 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Montoya, M.; Ives, J. Transformative practices to support first-generation college students as academic learners: Findings from a systematic literature review. J. First-Gener. Stud. Success 2021, 1, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction. In Knowledge, Education and Cultural Change; Brown, R., Ed.; Tavistock: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste; Nice, R., Translator; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Robinson, J.G., Ed.; Greenwood Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau, A. Invisible Inequality: Social Class and Childrearing in Black Families and White Families. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2002, 67, 747–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesters, J.; Watson, L. Returns to education for those returning to education: Evidence from Australia. Stud. High. Educ. 2014, 39, 1634–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croxford, L.; Raffe, D. Social class, ethnicity and access to higher education in the four countries of the UK: 1996–2010. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2014, 33, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, L.; Brown, M. Many happy returns! An exploration of the socio-economic background and access experiences of those who (re)turn to part-time higher education. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2019, 39, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, D.J. Conducting Web-Based Surveys. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2001, 7, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; Chapter 13. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; Sage: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, O. Supporting Students in Online, Open and Distance Learning; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Writing Feedback (WF) | Connect Live (CL) | |

|---|---|---|

| Service | Writing submission | Online live chat |

| Offered when | 24/7 | Six days a week (Mon–Sat) |

| Response time | 24–48 h | Approx 30 min |

| Types of submissions | Essays, reports, résumé, etc., up to 5000 words | Course/subject-related questions |

| Responder | One-to-one from suitable responder/subject specialist | One-to-one from suitable responder/subject specialist |

| Additional functions | Collaborative whiteboard for file sharing, maths, science-related queries | |

| Feedback | Written feedback on grammar, structure, readability Academic help but not answers | Oral feedback related to the question Academic help but not answers |

| Number of Students in Cohort | Users | Percentage | Uses | Average No. of Uses | Max No. of Uses by Individual | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-year undergraduates | 380 | 74 | 19% | 451 | 6 | 17 |

| All other undergraduates | 627 | 194 | 31% | 566 | 3 | 17 |

| Postgraduate | 401 | 115 | 29% | 651 | 6 | 14 |

| Total | 1408 | 383 | 1668 |

| Number of Students | Users | Percentage | Unique Instances of Use | Average No. of Uses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (2018/2019) | 644 | 113 | 17.5% | 509 | 4.5 |

| Total (2019/2020) | 764 | 270 | 35% | 1159 | 4.3 |

| Student Questions | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connect Live | PG | UG | PG | UG | |

| Where is the feedback | 1 | 1 | |||

| How to search for articles | 1 | 1 | |||

| How to design a survey | 1 | 1 | |||

| How to approach a question | 1 | 5 | 8 | 14 | |

| How to critique | 1 | 1 | |||

| Writing Feedback | |||||

| Submit assignment questions for review, e.g., Have I interpreted it correctly and answered it correctly? | 25 | 27 | 17 | 26 | 95 |

| Referencing | 18 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 35 |

| Academic conventions (Structure, layout, analysis, clarity, academic language, flow, style) | 17 | 6 | 3 | 13 | 39 |

| Grammar, spelling, punctuation | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 14 |

| Any help | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 11 |

| Word count | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||

| English as an Additional Language learner | 2 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 16 |

| Better mark/improvement | 4 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Plagiarism | 1 | 1 | |||

| Job reference | 1 | 1 | |||

| Transcription service | 1 | 1 | |||

| Questions and Responses | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1: About the survey | ||||||||

| Q2: Plain Language Statement.Click to consent. | ||||||||

| Q3: Have you used Studiosity? | Yes 26 (63.41%) | No 15 (36.59%) | 41 | |||||

| Q4: If you haven’t used Studiosity, please indicate why not | Don’t see the relevance. 1 (5.88%) | Lack of time 6 (35.29%) | Concerned about the feedback that will be received. 0 | Other 10 (58.82%) | 17 | |||

| Q5: How did you hear about Studiosity? | Programme Chair 16 (29.63%) | Tutor 9 (16.67%) | Fellow Student 3 (5.56%) | Moodle 21 (38.89%) | Don’t know about it. 3 (5.56%) | Other 2 (3.70%) | 54 | |

| Q6: Have you used the WF service? | Yes 24 (58.54%) | No 17 (41.46%) | 41 | |||||

| Q7: What motivated you to use the WF service? | 22 | |||||||

| Q8: To what extent did the feedback you received help you to improve your assignment? | Major improvements 9 (31.03%) | Minor improvements 16 (55.17%) | Not at all 3 (10.34%) | Made worse. 1 (3.45%) | 29 | |||

| Q9: To what extent did the feedback you received help you to develop your academic writing skills? | Significantly 12 (44.44%) | To some extent 10 (37.04%) | Not at all 5 (18.52%) | 27 | ||||

| Q10: Please indicate which type of document(s) you requested feedback on. | Essay 20 (41.65%) | Case Study 6 (12.50%) | Scientific Report 6 (12.50%) | Thesis 5 (10.42%) | Text Analysis 5 (10.42%) | Other 6 (12.5%) | 48 | |

| Q11: How satisfied were you with Studiosity Assignment Feedback? | Extremely Satisfied 16 (57.14%) | Somewhat Satisfied 8 (28.57%) | Neither Satisfied or Dissatisfied 3 (10.71%) | Somewhat Dissatisfied 0 | Extremely Dis- satisfied 1 (3.57%) | 28 | ||

| Q12: Have you used the CL service? If not, why? | Yes 6 (15%) | No 34 (85%) | 40 | |||||

| Q13: How satisfied were you with the CL service? | Extremely Satisfied 4 (44.44%) | Somewhat Satisfied 0 | Neither Satisfied or Dissatisfied 3 (33.33%) | Somewhat Dissatisfied 0 | Extremely Dis- satisfied 2 (22.22%) | 9 | ||

| Q14: If you experienced any difficulties with using Studiosity please indicate what these were | 7 | |||||||

| Q15: Do you have any other comments to share about the value of the Studiosity service? | 16 | |||||||

| Q16: Any other comments? | 12 | |||||||

| Q17: Sex | Male 16 (40%) | Female 24 (60%) | 40 | |||||

| Q18: Modules * | 20 Psychology | 10 Sociology | 7 History | 3 Philosophy | 2 Literature | 30 PG | 35 | |

| Q19: Year of Study | 13 × 1st Y (32.5%) | 5 × 2nd Y (12.5%) | 1 × 3rd Y (2.5%) | 4 × 4th Y (10%) | 1 × 5th Y (2.5%) | 15 × PG (38%) | 1 × Staff (2.5%) | 40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Delaney, L.; Brown, M.; Costello, E. Between the Lines: An Exploration of Online Academic Help-Seeking and Outsourced Support in Higher Education: Who Seeks Help and Why? Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111147

Delaney L, Brown M, Costello E. Between the Lines: An Exploration of Online Academic Help-Seeking and Outsourced Support in Higher Education: Who Seeks Help and Why? Education Sciences. 2023; 13(11):1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111147

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelaney, Lorraine, Mark Brown, and Eamon Costello. 2023. "Between the Lines: An Exploration of Online Academic Help-Seeking and Outsourced Support in Higher Education: Who Seeks Help and Why?" Education Sciences 13, no. 11: 1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111147

APA StyleDelaney, L., Brown, M., & Costello, E. (2023). Between the Lines: An Exploration of Online Academic Help-Seeking and Outsourced Support in Higher Education: Who Seeks Help and Why? Education Sciences, 13(11), 1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111147