Abstract

Future educational professionals should possess both the academic and personal skills needed for resilience. These future professionals will face difficult situations, and the development of skills such as resilience is an important part of their training. The primary objective of this research paper is to study and analyze the links between the emotional intelligence, resilience, and personalities of undergraduates studying for different degrees in educational sciences. A quantitative analysis was performed with a non-experimental, descriptive, comparative, and correlational design. The sample results show above-average levels in all three dimensions, with resilience exhibiting the highest values. Regarding the influence of gender, males presented a higher level of resilience than females, while females tended to exhibit higher levels of spirituality. University students who studied physical activity and sport sciences were found to be more resilient and to have higher weighted emotional intelligence scores than students with other educational science degrees. Emotional clarity and repair corresponded directly with the subjects’ age. Emotional intelligence was positively correlated with repair, highlighting this variable as fundamental to resilience.

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the study of resilience in the 1960s, there have been many definitions proposed by various authors, and we highlight several of them below. When we use the term “resilience” in any investigation, we must provide a clear definition of the term, as it can have different meanings depending on authors’ approaches. For example, there are authors who support the idea that resilience refers to post-traumatic growth because they understand it as the ability to emerge unscathed from an adverse experience, to learn from it, and to eventually improve oneself as a result [1]. On the other hand, there are authors who define resilience as a process of overcoming and helping individuals to recover from adversity [2], thus differentiating it from the concept of post-traumatic growth [3]. As we understand it, resilience is the capacity to overcome emotional pain or difficult experiences and to be ourselves again [4]. The loss of a loved one, physical or mental abuse, abandonment, failure, poverty, etc., are all examples of situations that are difficult to overcome, but anyone can generate the biological, psychological, or social factors necessary to resist these situations and eventually recover from them.

The importance of having appropriate resilience when facing adverse situations, as demonstrated [5], is vital because it shows that the more adversities that one faces, the more resilience one has, which is a protective factor in the face of future adverse situations [5,6,7]. This attests to the fact that resilience is holistically conditioned by psychological, physiological, and sociological factors [8].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a study was conducted that compared different personality factors with resilience and well-being. Personality influences resilience and psychological well-being, and that these relations are context-dependent, which suggests the importance of integrating such contextual factors into future research [9].

Over the last several decades, educational systems have undergone numerous changes, mainly leaving behind the emotional needs of learners [10]. These changes must be reversed to restore the importance of emotional intelligence, since this is one of the main predictors of success in both academic and professional fields [11].

The value of personality during the learning process consists of various cognitive, affective, and social aspects, as well as the brain’s capacity for knowledge disposition [12]. According to [13], personality begins to form at birth, when the character of each subject begins to develop. A subject’s personality is determined by the presence and/or lack of differentiating elements according to which each subject characterizes his/her behavior [14]. Subjects who possess life satisfaction, higher resilience, and protective factors are also more likely to possess high emotional intelligence [15].

The use of resilient strategies and emotional repair have an impact on the life satisfaction of subjects [16], such that the most resilient subjects are those who possess greater abilities to distinguish, relate to, and manage their own emotions as well as those of others. Existence of a positive correlation between personality traits and resilience and a negative association with neuroticism has been shown [17]. Similarly, subjects with high resilience tend to have lower neuroticism, as well as higher agreeableness, extraversion, and responsibility [18].

Some researchers showed the correlation between resilience and various personality dimensions, such as extraversion and emotional stability, thus affirming that personality traits (Table 1) have an impact on subjects’ resilience [19].

Table 1.

Personality traits [20].

Personality components definitely influence resilience, with neuroticism exhibiting a negative correlation, while other factors exhibit a positive correlation with resilience (e.g., control under pressure, adaptability and support networks, control and purpose, and spirituality) [21].

It is important to remember that the objectives of a study should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART), meaning that they should be clear, well-defined, realistic, and have a specific deadline for completion. In this case, our objectives are focused on understanding the relationships between different factors and variables, such as personality, resilience, emotional intelligence, and sociodemographic aspects, in university students.

The main objective of this study is to identify the factors that influence the development of resilience, emotional intelligence, and personality in university students. More precisely, our specific objectives are as follows:

- To identify the personality components, resilience, emotional intelligence, and sociodemographic variables of university students;

- To investigate the relationships between personality, resilience, emotional intelligence, and sociodemographic aspects.

With these objectives in mind, we propose the following hypotheses. It is usually expected that male university students will show a higher level of resilience, while female university students show higher levels of emotional intelligence. Early childhood education undergraduates are expected to possess high levels of all variables. Finally, it is expected that university students will exhibit similar characteristics to those of other students with similar educational degrees. Emotional intelligence and resilience have a strong influence on the personalities of future professionals.

2. Materials and Methods

A descriptive (percentages and measures), comparative (comparison of variables), non-experimental (no intervention in the responses of the participants), and correlational quantitative study was carried out, measuring a single group of university students.

2.1. Variables and Instruments

The variables were gender, age, resilience, emotional intelligence, and personality; the relevant variables were measured based on the extraversion, neuroticism, sincerity, and psychoticism of the sample.

An ad hoc questionnaire was used, which included a record sheet with the sociodemographic variables in this study (gender, age, place of residence, and university degree). This ad hoc questionnaire was designed by researchers based on other tools and variables reported in the scientific literature. These experts participated in a qualitative and quantitative validation process.

The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), created by Connor and Davison in 2003, was employed in this study, using the Spanish version adapted by Crespo et al. (2014). This questionnaire consists of 25 items on a Likert-type scale with five points each, in which 0 = not at all, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, and 4 = almost always. The final score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater resilience.

The Trait Meta-Mood Scale 24 (TMMS-24) emotional intelligence test [22] and based on the Trait Meta-Mood Scale 48 [23], was also employed. This method evaluates the subject’s meta-knowledge of emotional states; it is composed of three dimensions with 8 items in each dimension, for a total of 24 items. It measures the subject’s level of agreement with each of the items on a Likert-type scale, in which 1 = not at all agree, 2 = somewhat agree, 3 = more agree, 4 = strongly agree, and 5 = totally agree.

The Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Revised-Abbreviated (EPQR-A) is the abbreviated version of the 100-item EPQR [24]; the current version consists of 24 items, with four subscales (Table 2), which are composed of 6 items each, with dichotomous response options (yes or no).

Table 2.

Four subscales of the EPQR-A Questionnaire.

2.2. Procedure

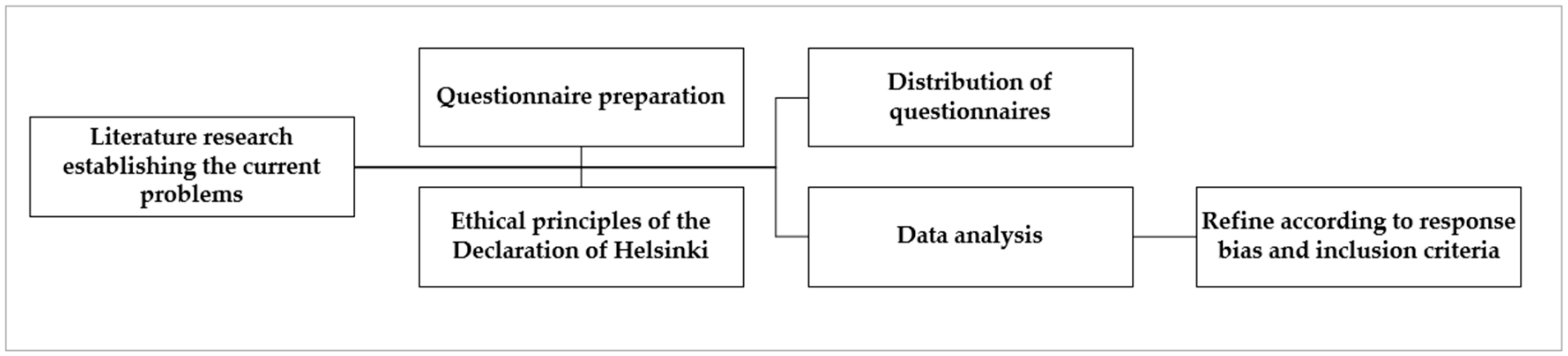

After obtaining all the necessary information from the literature, the study was performed using a Google form. Participation in the questionnaire had to be consented to by the students to ensure the anonymity of the data. The questionnaire explained the instruments used, the objective of the study, and the objectives to be achieved. Once the responses had been obtained and the invalid ones discarded, the data were collected in SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), as shown in Figure 1. The study complied with the ethical codes regulated by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1.

Study procedure.

2.3. Data Analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed using the mean (M), standard deviation (SD), and frequencies (%) of all variables. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to determine the contrasts between subjects, and Pearson’s bivariate correlation was employed, with significance levels of p < 0.05 and p < 0.01. The Excel package for data storage was used, and the data were imported to be processed in SPSS 25.0 software.

Sample

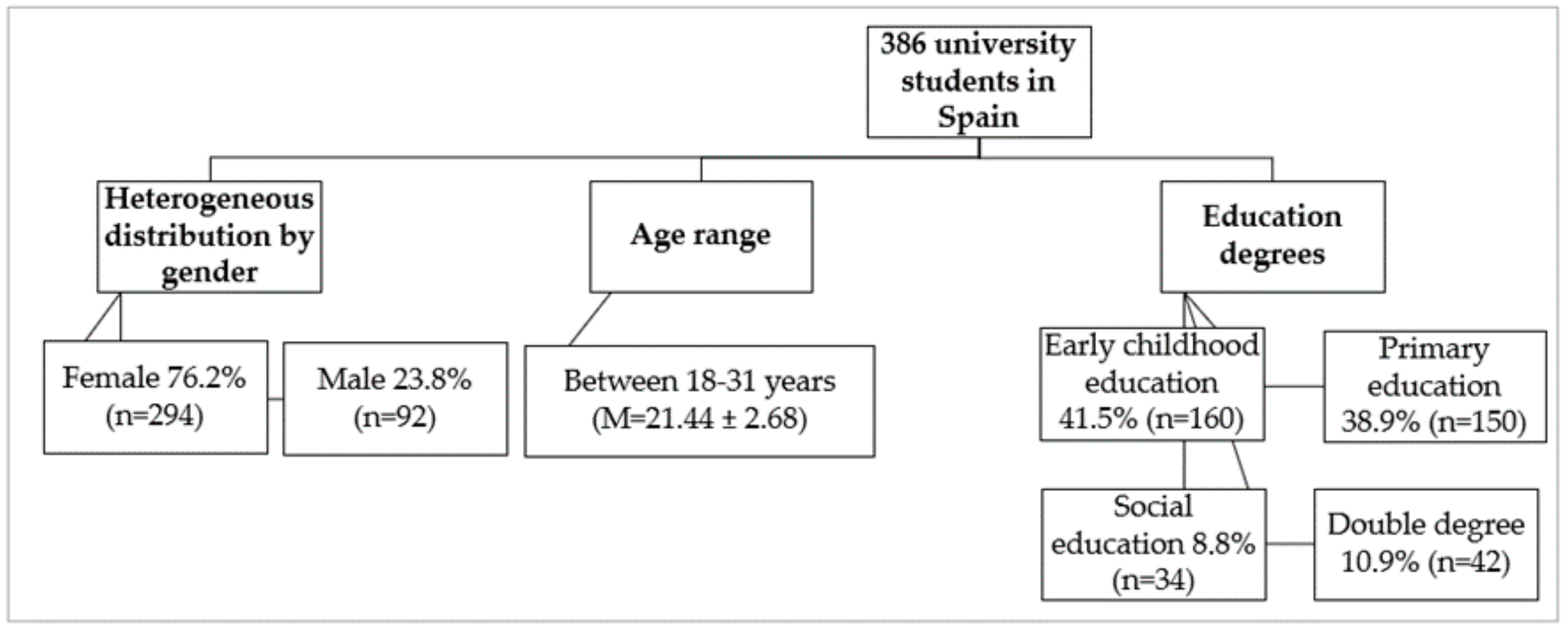

A total of 386 Spanish university students from different cities participated in the present study. The age range was between 18 and 31 years (M = 21.44 ± 2.68); 76.2% (n = 294) were women and 23.8% (n = 92) were men. Subjects reported studying the following educational degrees: early childhood education: 41.5% (n = 160), primary education: 38.9% (n = 150), social education: 8.8% (n = 34), and double degree: 10.9% (n = 42), see Figure 2. The subjects were chosen through a non-random sampling method for convenience based on their accessibility.

Figure 2.

Demographics of subjects in the study sample.

3. Results

The descriptive results of the psychosocial variables are shown in Table 3. The percentages values for emotional intelligence reflect that the subjects tended to have an adequate level of EI. For EIS, the mean values were M = 4.92 ± 3.67. Regarding resilience, most students showed a high level (77.7%; n = 300).

Table 3.

Descriptive results of psychosocial variables.

Next, EIS values are reported in Table 4 (M = 4.92 ± 3.67). With respect to emotional intelligence and its categories, the highest values were found in AT (M = 3.89 ± 0.67), and the lowest values were found in CL (M = 3.56 ± 0.72). Regarding resilience, the university students showed a high level (77.7%; n = 300). Regarding personality, extraversion had the highest mean level (M = 0.71 ± 0.31), while psychoticism had the lowest levels (M = 0.36 ± 0.16).

Table 4.

Descriptive results of psychosocial variables.

Next, correlations between sociodemographic features as functions of psychosocial variables were determined. First, Table 5 illustrates the correlation between the psychosocial variables of the subjects as a function of gender. A significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) in emotional intelligence between genders was found, with females (p ≤ 0.001) scoring higher in attention (M = 3.98 ± 0.62). Regarding personality, female subjects were found to show significantly (p ≤ 0.001) higher levels of neuroticism (M = 0.53 ± 0.29); by contrast, male subjects tended to show higher levels of sincerity, with M = 0.57 ± 0.25. Finally, regarding resilience and its categories, female subjects exhibited significantly higher levels of spirituality (p ≤ 0.001, M = 3.66 ± 0.93), whereas male subjects showed higher levels of PTSE (p = 0.039, M = 4.01 ± 0.72) and CUP (p ≤ 0.001, M = 3.72 ± 0.61). The highest levels for RS were found in male subjects (M = 3.86 ± 0.61), while female subjects exhibited a mean RS of M = 3.72 ± 0.60.

Table 5.

Psychosocial variables according to participants’ gender.

Table 6 shows the results of the psychosocial variables as a function of which degree subjects are pursuing. With respect to EI, university students pursuing DD had higher RP (M = 0.34 ± 0.26), while PE university students had the lowest RP levels (M = 3.44 ± 0.71). Regarding personality and its categories, the N of PE students tended to be higher (M = 0.52 ± 0.31) while that of DD students tended to have a lower mean (M = 0.34 ± 0.26).

Table 6.

Psychosocial variables according to the university degree of the participants.

PS was higher in S students (M = 0.40 ± 0.22) compared to that of PE students (M = 0.32 ± 0.17). Regarding resilience, university students from DD exhibited a higher mean in the PTSE category, while those from S exhibited lower levels (M = 4.42 ± 0.47 and M = 3.69 ± 0.73, respectively). For ASN, university students in DD had the highest values (M = 4.40 ± 0.41) while those in PE had the lowest values (M = 3.79 ± 0.73). To conclude, in RS and EIS, the DD university students obtained the highest means (M = 4.13 ± 0.44 and M = 3.82 ± 0.52, respectively), while the SOCE university students exhibited significantly lower values (M = 3.67 ± 0.56 and EIS, respectively).

4. Discussion

The sample was mainly composed of female university students. Regarding the descriptive results between emotional intelligence and resilience, the university students studied achieved adequate levels in all dimensions of EI, as well as high levels of resilience. This shows that the most resilient people also have the skills to perceive, assimilate, and manage their own emotions, as well as those of others [25]. With respect to the elements of emotional intelligence, the students exhibited the highest levels of attention, followed by repair and emotional clarity, which matches the findings reported in others studies [19].

Regarding resilience, the subjects reported higher levels of adaptability and support networks, as well as persistence, tenacity, and self-control, which are related to overcoming adverse situations that affect them negatively. This suggests that they were able to transform such situations into learning experiences, which could increase the levels of the resilience construct. According to our findings regarding the relationship between the sociodemographic aspects and psychosocial variables, there was no significant difference in the emotional intelligence sum based on gender, contrary to the findings of the study [25].

Additionally, male subjects reported higher levels of persistence, tenacity, and self-efficacy (PTSE), as well as higher control under pressure (CUP), while female subjects reported higher levels of spirituality [26,27]. Concerning personality, female subjects exhibited higher levels of neuroticism, specifically higher levels of anger and anguish, contrary to the data reported [28]. Concerning the relationship between psychosocial variables and the university degree of the subjects, university students with double degrees exhibited significantly higher levels of resilience compared to students pursuing other university degrees, being more persistent, more tenacious, and having greater self-control, as well as having greater adaptability and more support networks.

They also obtained higher levels for the resilience sum and emotional intelligence sum, with higher levels of emotional repair. These results may be related to sports and physical activity [29], since these students experience greater self-satisfaction and develop the ability to react quickly and effectively to stressful experiences. Primary education students exhibited higher levels of neuroticism [30], while social education students showed a higher percentage of spirituality.

Concerning the study variables, which depend on the observed psychosocial aspects of the university students and their degrees of emotional attention, it can be affirmed that the university students who pay the most attention to their emotions also present the highest level of neuroticism. This is in contrast to those who present an adequate level of emotional attention and obtain higher levels of sincerity. Regarding resilience, those who show greater control under pressure also tend to show adequate or too much emotional attention and are able to act on that awareness [8]. This is in contrast to those who give too little attention to their emotions, which tends to result in low values of total resilience.

5. Conclusions

Based on the hypotheses and objectives of this study, we conclude the following:

Male students tend to show higher levels of resilience, persevere more in their work, and have greater self-control under pressure. In contrast, female students tend to show greater emotional intelligence with a higher degree of attention to their emotions.

The early childhood education sample did not show high levels on the personality survey, nor in any of its variables, instead showing average levels in each of them; thus, it is estimated that in all the dimensions with significant values, these university students exhibit appropriate average levels. There is evidence that the students pursuing degrees in education and physical activity obtain higher values than other university students with respect to resilience and being able to repair their emotions.

The university students pursuing primary education had the highest negative levels in their personality traits, being the most neurotic of all the groups in this study, and the university students studying social education were the most psychotic in comparison with the groups in our sample. Our research emphasizes the importance of emotional intelligence and resilience for our future teachers and the importance of taking these features into account at personal and academic levels. Furthermore, it suggests the need to work on improving these skills during teacher training.

6. Limitations and Implications

In terms of the limitations of this study, it is noted that the sample used in the study could be improved by including other university degrees, rather than only education science students, to support more specific conclusions. Another limitation is the large number of female subjects in the sample.

Furthermore, it is necessary to continue studying these two phenomena in depth, looking for new psychological and sociodemographic variables that can establish new relationships. An option for future work would be to compare these results with those obtained using other similar scales available in the scientific literature.

On the other hand, the practical consequences of this study underscore the need to promote education regarding emotional intelligence and resilience to improve personal well-being. In addition, it can contribute to improvements in the design, development, and evaluation of intervention programs in different populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V.-J. and M.O.-C.; methodology, I.O.-C.; validation, A.O.-C.; formal analysis, M.O.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V.-J.; writing—review and editing, A.S.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project (CE-CAM-22): Emotional Intelligence and Education. UNESCO CAM.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to personally identifiable information was removed.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ong, A.D.; Bergeman, C.S.; Bisconti, T.L.; Wallace, K.A. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 730–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, J.; Delfabbro, P.H. Psychological resilience in disadvantaged youth: A critical overview. Aust. Psychol. 2004, 39, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Robles, A.; Segura-Robles, L. Secundaria y profesorado: Un estudio entre los futuros Profesores de secundaria. In Educación Global en Contextos Formativos; Padilla, D.B., Olmedo, E., de la Rosa, A., Belmonte, J.L., Eds.; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 101–114. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=860408 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Carazo, V. Resiliencia y coevolución neuroambiental. Rev. Educ. 2018, 42, 528–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Bonanno, G.A. Ajuste psicológico durante el brote global de COVID-19: Una perspectiva de resiliencia. Trauma Psicológico Teoría Investig. Práctica Política 2020, 12, S51. [Google Scholar]

- Karataş, Z.; Tagay, Ö. Las relaciones entre la resiliencia de los adultos afectados por la pandemia de COVID en Turquía y el miedo al COVID-19, el sentido de la vida, la satisfacción con la vida, la intolerancia a la incertidumbre y la esperanza. Pers. Difer. Individ. 2021, 172, 110592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero-Moreno, S.; Lacomba-Trejo, L.; Tamarit, A.; Pérez-Marín, M.; Montoya-Castilla, I. Ajuste psicoemocional en padres de adolescentes: Un análisis transversal y longitudinal del impacto de la pandemia de COVID. D. Enfermería Pediátrica 2021, 59, e44–e51. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, M.; Saavedra, S. Resilience: Physiological assembly and phychosocial factors. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 132, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmony, F.U.; Kanbach, D.K.; Stubner, S. Entrepreneurs in times of crisis: Effects of personality on business outcomes and psychological well-being. Traumatology 2022, 28, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Casares, M.J.; Aguaded-Ramírez, E.M. Evaluación de la Inteligencia Emocional en el alumnado de Educación Primaria y Educación Secundaria. Rev. Educ. Univ. Granada 2019, 26, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez, D. Aproximación crítica a la Inteligencia Emocional como discurso dominante en el ámbito educativo. Rev. Española Pedagog. 2018, 76, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tacca, D.; Tacca, A.; Alva, M. Estrategias neurodidácticas, satisfacción y rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios. Cuad. Investig. Educ. 2019, 10, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos Atienza, R. Prevención de Riesgos Laborales para el Técnico Auxiliar de Enfermería; Formación Alcalá: Madrid, Spain, 2018; ISBN 978-84-13-01156-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda, D.; Mahecha, J. Autorregulación del aprendizaje y rasgos de personalidad en estudiantes universitarios. Rev. Innova Educ. 2022, 4, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulic, I.M.; Crespi, M.C.; Cassullo, G.L. Evaluación de la Inteligencia Emocional, la Satisfacción Vital y el Potencial Resiliente en una muestra de estudiantes de Psicología. Anu. Investig. 2010, 17, 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Limonero, J.T.; Tomás-Sábado, J.; Fernández-Castro, J.; Gómez-Romero, M.J.; Ardilla-Herrero, A. Estrategias de afrontamiento resilientes y regulación emocional: Predictores de satisfacción con la vida. Behav. Psychol./Psicol. Conduct. 2012, 20, 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Fayombo, G. The Relationship between Personality Traits and Psychological Resilience among the Caribbean Adolescents. Int. J. Psychol. Stud. 2010, 2, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dematteis, M.B.; Grill, S.S.; Posada, M.C. Sentido de Coherencia y Resiliencia: Características salugénicas de personalidad. In IV Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología XIX Jornadas de Investigación VIII Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del 252 MERCOSUR; Facultad de Psicología-Universidad de Buenos Aires: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A.; Saklofske, D.H. Promoting individual resources: The challenge of trait emotional intelligence. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 65, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T.; Furnham, A. Personality and Intellectual Competence; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Osimo, S.A.; Aiello, M.; Gentili, C.; Ionta, S.; Cecchetto, C. The Influence of Personality, Resilience, and Alexithymia on Mental Health During COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 630751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N.; Ramos, N. Validity and Reliability of the Spanish Modified Version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychol. Rep. 2004, 94, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D.; Goldman, S.L.; Turvey, C.; Palfai, T.L. Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In Emotion, Disclosure, and Health; Pennebaker, J.W., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck, S.B.G.; Eysenck, H.J.; Barrett, P. Una versión revisada de la escala de psicoticismo. Pers. Difer. Individ. 1985, 6, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso-Besio, C.; Cuadra-Peralta, A.; Antezana-Saguez, I.; Avendaño-Robledo, R.; Fuentes-Soto, L. Relación entre inteligencia emocional, satisfacción vital, felicidad subjetiva y resiliencia en funcionarios de educación especial. Estud. Pedagógicos 2013, 39, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, D.A.G.; Sánchez, U.D.; Flores, F.G.M.; Rodríguez, M.A.O.; Reyes, R.A. Resiliencia, género y rendimiento académico en jóvenes universitarios del Estado de Morelos. Rev. ConCiencia EPG 2021, 6, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, I.; Castro, M. Análisis de los niveles de resiliencia en función del género y factores del ámbito educativo en escolares. ESHPA 2018, 2, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mesa Jacobo, J.R. Inteligencia Emocional, Rasgos de Personalidad e Inteligencia Psicométrica en Adolescentes. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Murcia, Murcia, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Puertas Molero, P.; González Valero, G.; Sánchez Zafra, M. Influencia de la práctica físico deportiva sobre la Inteligencia Emocional de los estudiantes: Una revisión sistemática. ESHPA 2017, 1, 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Carty-Vásquez, A.M.; Josco-Mendoza, J.; Ocaña-Fernández, Y. La empatía en estudiantes universitarias de educación primaria. Práxis Educ. 2020, 16, 358–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).