‘Getting into the Nucleus of the School’: Experiences of Collaboration between Special Educational Needs Coordinators, Senior Leadership Teams and Educational Psychologists in Irish Post-Primary Schools

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Rationale

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Quality

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Participants

2.5. Ethics

2.6. Limitations

2.7. Data Collection

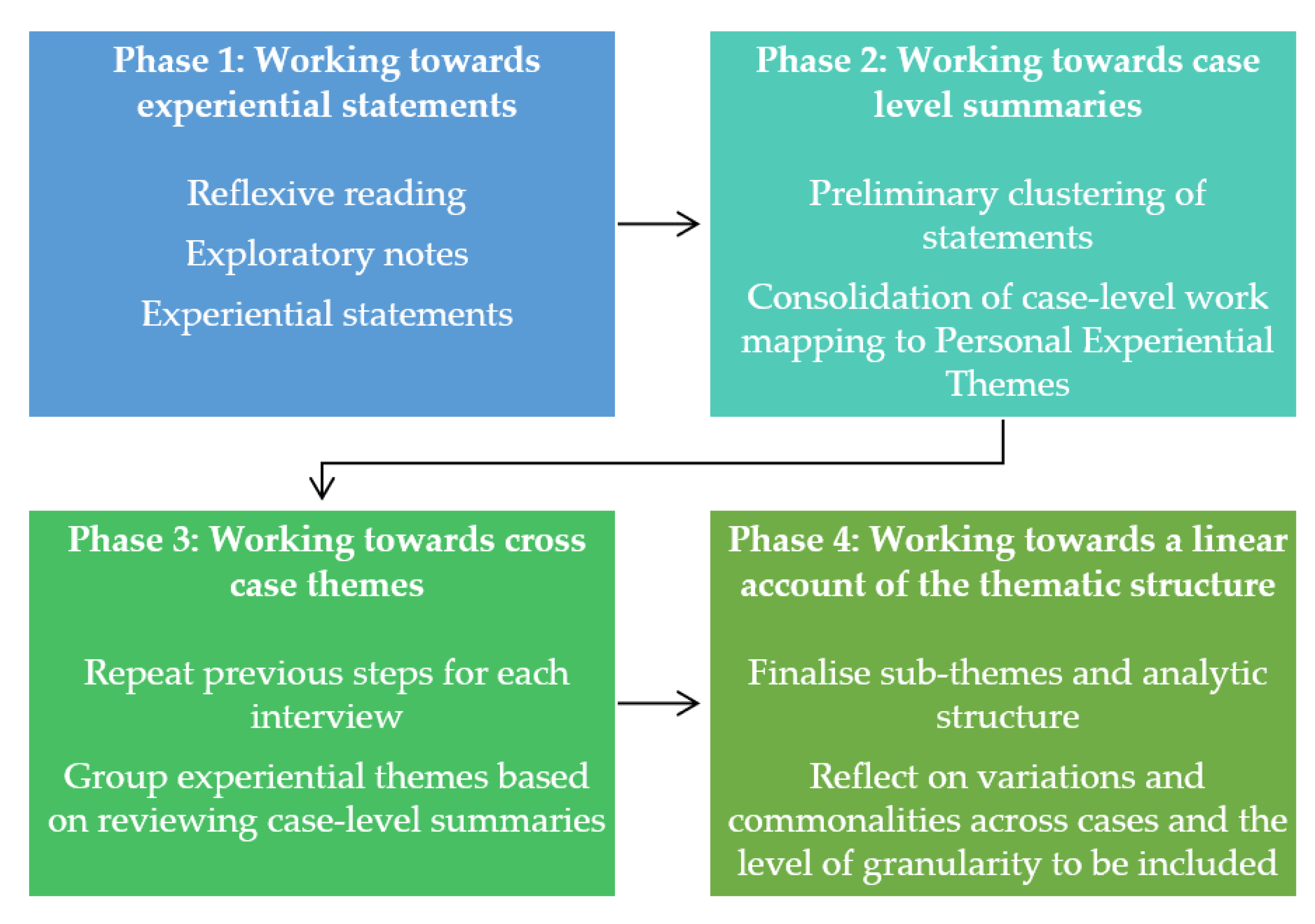

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Interpersonal Connections

3.1.1. From Battle to Luck

It wasn’t for the good of the child, d’you know. It wasn’t. With [current psychologist] it always is. So I’m very lucky and I hope that we still have her, I got a letter the other day to say she’s appointed to us for next year again. Thank God. I’m very lucky.

I’d like a team, because then you could, you know, have an expert in maybe all of those areas or a few of us could have a few of the skills that we could share. So quite often I feel it’s the tail wagging the dog. You know, rather than the other way around. But look, we’ll fight the good fight and we’ll keep asking for it. I might get it from private prayer.

3.1.2. Far and Beyond

When we closed in January [due to COVID], we asked them [Special Needs Assistants and Special Education Teachers] to phone on a regular basis all of their students because they weren’t the type that were going to engage too much with school anyway. Some of them went far and beyond what they were called to do.

I have to say I’m tired. […] I’’s like a piece of elastic really, and I don’t seem to have the personality to say, well I can’t do that because if it’s not done I’m looking at a child’s face and I can’t sleep at night then. I mean, I can’t, you know. So by our nature I suppose in the role we’re not as kind of I suppose strict or as disciplined as we could be if you like.

It’s not mentioned, It’s not catered for, it can be an AP [assistant principal] II post, it can be an AP I post. It can have hours, it can have no hours and no money. It can be anything. It can be enough for teachers to resign from it.

You can’t have box-tickers. You have to have people who look beyond the 40-min class or the one-hour class and see the big picture. And it’s becoming more complicated.

Instead of getting a bunch of carrots, or all the carrots, I may have got half the carrots, but I’m very happy to take half the carrots and the next time I’d like to–- because now he’s getting, he’s really starting to get it as well, am, and then the next time, then I’ll get a little bit more and we’ll build it.

3.1.3. Holding Hands

The SENCO is the person that mediates it for the family and explains it and helps them and supports them and is that little light in the tunnel that helps them see the other side when people are giving them names and labels and talking about their child in very deficit-oriented language, because tha’’s just the nature of the job. The SENCO is the person that holds their hands kind of through the process and helps them see the journey and the path forward and helps them see you know, this is how we’re gonna help you, help your child achieve their potential. And they sound like real catch words and buzz words, but they actually really mean something when you, when you’re in the middle of this and you want someone to say, but what can we do to help? They’re the person that helps you with the help. That’s quite an inspiring role, isn’t it? I don’t know how you capture that in a job description.

3.2. Theme 2: Expertise in Managing Layers

3.2.1. SENCO as Filter

You want them to be at the table where the decisions are made and you want that voice to be heard and you want somebody with a really good knowledge of, just of special needs and where it’s going and to be able to filter that policy throughout the school.

I feel it more now. You know that kind of draw, where I’ve realised the job is so administrative and operational that that link to kind of the student isn’t as strong as it would have been previous to the new model, but then you do have more—because you have to have more stronger links to the teachers and the SNAs and parents. You know, but the actively like going in and doing, you know, you know, supporting students with dyslexia or supporting students with behavioural—or you know that support which would have been the traditional role of the SENCO. That has kind of become more for the team.

Is part of their role to link with NEPS and has that been made explicitly a part of their role that they’ll kind of take that on? I’m not sure you know, or is it just that they need an assessment and ring that person you know, who can do the assessment for you?

It’s a really important role ‘cause they do oversee not just, you know, I think it’s not just about overseeing the needs for some and for a few. It’s also about good preventative approaches and supporting staff with the implementation of those preventative approaches and liaising, you know, looking up to us, and to the NCSE [National Council for Special Education] or whatever for you know information like that so and and time should be given to that role.

3.2.2. SLT Oversight of Layers

In a sterile world of governance in schools I’m the accountable officer to all that exists in the school. But I suppose first and foremost I’m primarily motivated that all children em irrespective of background need, when you come into this school, achieve the potential. So there’s a, there’s a deeper ideological viewpoint there, you know. So every child’s achieving their potential, wherever that potential is at, then we use, start to use the infrastructure and instruments of the school to try and meet those needs. And, it’s my view that I identify, see where the potential shortcomings are, whether that be within the infrastructure of the school, or the channels of communication or recording spaces, and then having the suitable candidates, personnel in terms of the right roles and responsibilities.

3.2.3. NEPS as Hub

Our role is often just providing a space, a respectful space where people can slow down and reflect and think about, you know, rather than just running around all the time in a stressed state. Because often you know a lot of our work involves, you know, kids in some form of stress, and teachers stressed as well.

NEPS started out doing a lot of assessments, you know that kind of a way. And we started out as being gatekeepers and the resource hours and things. So, so trying to change any kind of a system like that is going to be really hard and take a really long time.

It’s [wellbeing] given us a way in, it’s given us something else to talk about rather than resources and we’re seen in a kind of a different light now.

And that’s getting into the nucleus of, the nerve centre of the school and saying okay, how do we get in here and sort of shape and influence at a systems level the decision making, the influence of the school community. As opposed to starting, coming in at a case level, just on the ground to respond.

3.3. Theme 3: Working around Silos

3.3.1. Silo versus Deliberately Constructed Organism

The absence maybe of an SEN role and an SEN coordinator’s role—you can, you can really see how how how you’re very siloed into that SEN department. You’re a department, you’re one little, tiny piece of the secondary school.

Schools are organic sort of organisations, they ebb and flow and where, where there’s human life we have to be flexible to meet these different needs and so, but then we need systems to operate in that space because if we don’t then things can fall pretty easily and the most vulnerable, in particular children with SEN, lose out in that space. So quite right, we need to have appropriate infrastructure and systems operating in and through that process. But equally we need the right personnel in and around that process. But fundamentally we need to have all of this built on proper foundations, and that speaks to having core values and having a very clear sense of purpose of vision of what we want to achieve in participating in this space.

We have to feed all of that by reliable and sound information. So we rely on outside agencies like our NEPS psychologist, like the NCSE [National Council for Special Education], Junior Cycle, PDST [Professional Development Service for Teachers], all these to come in and speak to us, so it’s just not just Peadar off on a rant here, but that it’s, this is, guys, where we need to go as a school.

3.3.2. Language Shapes Silos

People like to talk about nurture groups and all that sort of stuff and they like to talk about restorative practice. Really what you’re doing is you’re just doing the right thing for those children, and so we would have gone after that actively.

A few of us have done the post grad in SEN and would have all come to the conclusion that we were uneasy with the term [special]. I think also within the—so we’ve been using additional, maybe for last three years, and actually probably since maybe 2017 is when we eliminated the term special altogether, and that came in in line with the new model, the circular there, we decided that was going to be our our linguistical change.

Our conversations were always so narrow, like that they had a very strong agenda about getting an assessment or whatever, so that’s, it seemed to be from the get-go, that’s what they wanted to use their NEPS time for, and there was kind of very little negotiation.

Resource is the word we had been using, but we’re now trying to do better because we know better and we’re trying to call it learning support. I’m doing my best, but it’ll take a while for that to establish.

3.3.3. The Value of Collaboration

You really have to be there a while to have developed the relationships that they trust you enough to say, we’re going to put the [cognitive assessment] aside for now, we’re gonna try this way, and just see if we get the same information.

4. Discussion

5. Implications and Recommendations

5.1. NEPS Facilitating Collaboration

5.2. Formalising the SENCO Role

5.3. Teacher Professional Learning

5.4. Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fitzgerald, J.; Radford, J. The SENCO role in post-primary schools in Ireland: Victims or agents of change? Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2017, 32, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; Banks, J. Inclusion at a Crossroads: Dismantling Ireland’s System of Special Education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, L. On the necessary co-existence of special and inclusive education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederickson, N.; Cline, T. Special Educational Needs, Inclusion and Diversity, 3rd ed.; Open University Press: Milton Keynes, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rix, J.; Sheehy, K. Nothing special–the everyday pedagogy of teaching. In The SAGE Handbook of Special Education, 2nd ed.; Florian, L., Ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 459–474. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, J.M.; Felder, M.; Ahrbeck, B.; Badar, J.; Schneiders, K. Inclusion of All Students in General Education? International Appeal for A More Temperate Approach to Inclusion. J. Int. Spec. Needs Educ. 2018, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCSE. Policy Advice on Special Schools and Classes: An Inclusive Education for an Inclusive Society? National Council for Special Education: Trim, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- NCSE. About Us—National Council for Special Education. 2022. Available online: https://ncse.ie/about-us (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Hornby, G. Special Education Today in New Zealand; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; Volume 28, pp. 634–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornby, G. Inclusive special education: Development of a new theory for the education of children with special educational needs and disabilities. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2015, 42, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCSE. Delivery for Students with Special Educational Needs: A Better and More Equitable Way; National Council for Special Education: Trim, Ireland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- DES. Circular to the Management Authorities of All Post Primary Schools: Secondary, Community and Comprehensive Schools and the Chief Executive Officers of the Education and Training Boards: Special Education Teaching Allocation Circular 14/2017; Department of Education and Skills: Westmeath, Ireland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NEPS. A Continuum of Support for Post-Primary Schools: Guidelines for Teachers; National Educational Psychological Service: Dublin, Ireland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- NEPS. National Educational Psychological Service: Overview of NEPS Service. Government of Ireland. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/service/5ef45c-neps/#overview-of-neps-service (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Ekins, A. The Changing Face of Special Educational Needs: Impact and Implications for SENCOs, Teachers, and Their Schools, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, J.; Radford, J. Leadership for inclusive special education: A qualitative exploration of SENCOs’ and principals’ Experiences in secondary schools in Ireland. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 26, 992–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P. Consultation as a framework for practice. In Frameworks for Practice in Educational Psychology, 2nd ed.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2017; pp. 194–216. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, J.E.; Nelson, J.R.; Gutkin, T.B.; Shwery, C.S. Teacher Resistance to School-Based Consultation with School Psychologists: A Survey of Teacher Perceptions. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2004, 12, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Farrell, P.; Kinsella, W. Research Exploring Parents’, Teachers’ and Educational Psychologists’ Perceptions of Consultation in a Changing Irish Context. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2018, 34, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, H. ‘The SEND Code of Practice has given me clout’: A phenomenological study illustrating how SENCos managed the introduction of the SEND reforms. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2019, 46, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DfE & DoH. Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice: 0 to 25 Years. Department for Education & Department of Health. 2015. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/398815/SEND_Code_of_Practice_January_2015.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Petersen, L. A national perspective on the training of SENCOs. In Transforming the Role of the SENCO: Achieving the National Award for SEN Co-Ordination; Hallett, F., Hallett, G., Eds.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2010; pp. 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- DES. Circular to the Managerial Authorities of Recognised Secondary, Community and Comprehensive Schools and The Chief Executives of Education and Training Boards: Leadership and Management in Post-Primary Schools Cl 03/18; Department of Education and Skills. 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/collection/department-of-education-and-skills-annual-reports/ (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Kjaer, B.; Dannesboe, K.I. Reflexive Professional Subjects: Knowledge and Emotions in the Collaborations between Teachers and Educational-Psychological Consultants in a Danish School Context. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2019, 28, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi-Aghdam, S. Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) as an Emergent System: A Dynamic Systems Theory Perspective. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2017, 51, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, T.; Ainscow, M. Index for Inclusion: Developing Learning and Participation in Schools, 3rd ed.; Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, G. An epistemology for inclusion. In A Psychology for Inclusive Education: New Directions in Theory and Practice; Hick, P., Kershner, R., Farrell, P.T., Eds.; Taylor and Falmer: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D.M. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, M.; Shaw, R.; Flowers, P. Multiperspectival designs and processes in interpretative phenomenological analysis research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2019, 16, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardley, L. Demonstrating validity in qualitative psychology. In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods, 3rd ed.; Smith, J.A., Ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2015; pp. 257–272. [Google Scholar]

- Korstjens, I.; Moser, A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oxley, L. An examination of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA). Educ. Child Psychol. 2016, 33, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member Checking. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brear, M. Process and Outcomes of a Recursive, Dialogic Member Checking Approach: A Project Ethnography. Qual. Health Res. 2019, 29, 944–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen-Freeman, D. On Language Learner Agency: A Complex Dynamic Systems Theory Perspective. Mod. Lang. J. 2019, 103, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larsen-Freeman, D. Complex, Dynamic Systems: A New Transdisciplinary Theme for Applied Linguistics? Lang. Teach. 2012, 45, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. Circular 0055/2022 Exemptions from the Study of Irish—Post-Primary. Department of Education. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/circular/28b2b-exemptions-from-the-study-of-irish-primary/ (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Hamre, B.; Hedegaard-Sørensen, L.; Langager, S. Between psychopathology and inclusion: The challenging collaboration between educational psychologists and child psychiatrists. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 22, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thornberg, R. Consultation Barriers Between Teachers and External Consultants: A Grounded Theory of Change Resistance in School Consultation. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 2014, 24, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.S.; Hazel, C.E.; Barrett, C.A.; Chaudhuri, S.D.; Fetterman, H. Early-Career School Psychologists’ Perceptions of Consultative Service Delivery: The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 2018, 28, 105–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J.; Lynch, J.; Martin, A.; Cullen, B. Leading Inclusive Learning, Teaching and Assessment in Post-Primary Schools in Ireland: Does Provision Mapping Support an Integrated, School-Wide and Systematic Approach to Inclusive Special Education? Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, F. Can SENCOs do their job in a bubble? The impact of COVID-19 on the ways in which we conceptualise provision for learners with special educational needs. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2021, 48, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, J.; Radford, J. Secondary SENCo leadership: A universal or specialist role? Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2011, 38, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skerritt, C.; McNamara, G.; Quinn, I.; O’Hara, J.; Brown, M. Middle leaders as policy translators: Prime actors in the enactment of policy. J. Educ. Policy 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperrider, D.; Whitney, D. A Positive Revolution in Change: Appreciative Inquiry. In The Change Handbook: The Definitive Resource on Today’s Best Methods for Engaging Whole Systems; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2005; p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- DES. Guidelines for Post-Primary Schools: Supporting Students with Special Educational Needs in Mainstream Schools; The Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Improving Schools in Scotland: An OECD Perspective; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rawdon, C.; Sampson, K.; Gilleece, L.; Cosgrove, J. Developing an Evaluation Framework for Teachers’ Professional Learning in Ireland: Phase 1; Educational Research Centre: Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Teaching Council. Teachers’ Learning (CPD)—Teaching Council. The Teaching Council—An Chomhairle Múinteoireachta. 2015. Available online: https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/teacher-education/teachers-learning-cpd-/ (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Rose, D.H.; Gravel, J.W.; Gordon, D.T. Universal Design for Learning. In The SAGE Handbook of Special Education, 2nd ed.; Florian, L., Ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 475–490. [Google Scholar]

- Gulliford, A. Evidence-based practice in educational psychology: The nature of the evidence. In Educational psychology: Topics in Applied Psychology, 2nd ed.; Cline, T., Gulliford, A., Birch, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Saoirse is an SENCO in a mixed rural DEIS school serving a large town and surrounding rural area (the Delivering Equality in Schools (DEIS) scheme provides additional resources and funding to schools that serve disadvantaged communities. ‘Deis’ means ‘opportunity’ in the Irish language). Almost half of the school’s 300 students are on the SEN register, with one-third experiencing complex needs. The school has an ASD class. The SENCO role is part of an Assistant Principal I post that includes other leadership duties. Saoirse holds an Assistant Principal II post but is currently acting as an Assistant Principal I. She has completed the postgraduate diploma in SEN. Saoirse has four hours per week assigned to Assistant Principal I duties, with two hours assigned to the SENCO role. |

| Síle works in an all-girls private fee-paying school with approximately 365 students, with around 20 on the SEN register. The school does not currently have an SEN team. Síle has completed a postgraduate diploma in SEN. Síle holds an Assistant Principal I post, which does not include SENCO duties. |

| Sinéad works in a DEIS school in a city, with a linguistically and culturally diverse student population. All students are on the Additional Educational Needs (AEN) register, with records kept of students receiving support across the Continuum of Support. Sinéad has completed a Postgraduate Diploma in SEN and holds an Assistant Principal II position. Sinéad and the AEN team have flexibility within their timetables to complete their duties. |

| Peadar has a post-graduate qualification in educational leadership and is the principal of a mixed DEIS school. He joined the school four years ago as principal, when enrolment was in decline; numbers have since increased. The school serves a large town and surrounding rural area. Of the 320 students in the school, 30% are on the SEN register and there are two classes for students with ASD. There is a SENCO in the school. |

| Paula is the deputy principal of a rural DEIS school with 380 students. The SENCO role is distributed across one AP I post and two AP II posts. Approximately 30% of students have psychological reports, and there is an ASD class in the school. |

| Patricia is the principal of a mixed school in a large town with 800 students. She completed a postgraduate diploma in SEN and has worked in the school for almost 40 years, becoming principal in 2014. There is an SEN team and a SENCO who is an AP II post-holder. The school has two ASD classes and includes students with a variety of complex needs. |

| Neasa completed a psychology degree and post-graduate qualification in primary teaching. She taught in primary school junior classes. She qualified as an Educational Psychologist via a master’s degree. Neasa previously worked with an all-girls city school with a reputation for academic achievement, and with a mixed Educate Together city school. She currently works with a large mixed DEIS school. |

| Nóra trained as a primary school teacher and taught in a special school for children with mild General Learning Disabilities. She completed a psychology degree and qualified as an Educational Psychologist via a doctoral programme in the UK. She worked in England before returning to NEPS. There was an emphasis on consultation in her training and when she joined NEPS. Nóra has worked with her current two post-primary schools for the past 9–10 years (both mixed post-primary schools with 300–350 pupils, one rural and one near a city). |

| Nuala worked as a primary school teacher in the UK before qualifying as an Educational Psychologist via a doctoral programme. She worked as a senior Educational Psychologist in England with children and families from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds and with a mix of large/small, rural/urban post-primary schools; most were academy schools. Nuala returned to Ireland some years ago and has been working with NEPS since then; she has worked with one private post-primary school and two large rural post-primary schools. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holland, M.; Fitzgerald, J. ‘Getting into the Nucleus of the School’: Experiences of Collaboration between Special Educational Needs Coordinators, Senior Leadership Teams and Educational Psychologists in Irish Post-Primary Schools. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030286

Holland M, Fitzgerald J. ‘Getting into the Nucleus of the School’: Experiences of Collaboration between Special Educational Needs Coordinators, Senior Leadership Teams and Educational Psychologists in Irish Post-Primary Schools. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(3):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030286

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolland, Maria, and Johanna Fitzgerald. 2023. "‘Getting into the Nucleus of the School’: Experiences of Collaboration between Special Educational Needs Coordinators, Senior Leadership Teams and Educational Psychologists in Irish Post-Primary Schools" Education Sciences 13, no. 3: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030286

APA StyleHolland, M., & Fitzgerald, J. (2023). ‘Getting into the Nucleus of the School’: Experiences of Collaboration between Special Educational Needs Coordinators, Senior Leadership Teams and Educational Psychologists in Irish Post-Primary Schools. Education Sciences, 13(3), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030286