Unplugging for Student Success: Examining the Benefits of Disconnecting from Technology during COVID-19 Education for Emergency Planning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Stress: A Global Health Problem

2.2. Adolescents and Academic Stressors

2.3. Consequences of Chronic Stress in Adolescents

2.4. Communication and Information Technologies and Their Impact on Mental Health

3. Methodology

4. Unplugged Day Activity

5. Data Collection Procedures

6. Survey

7. Data Analysis

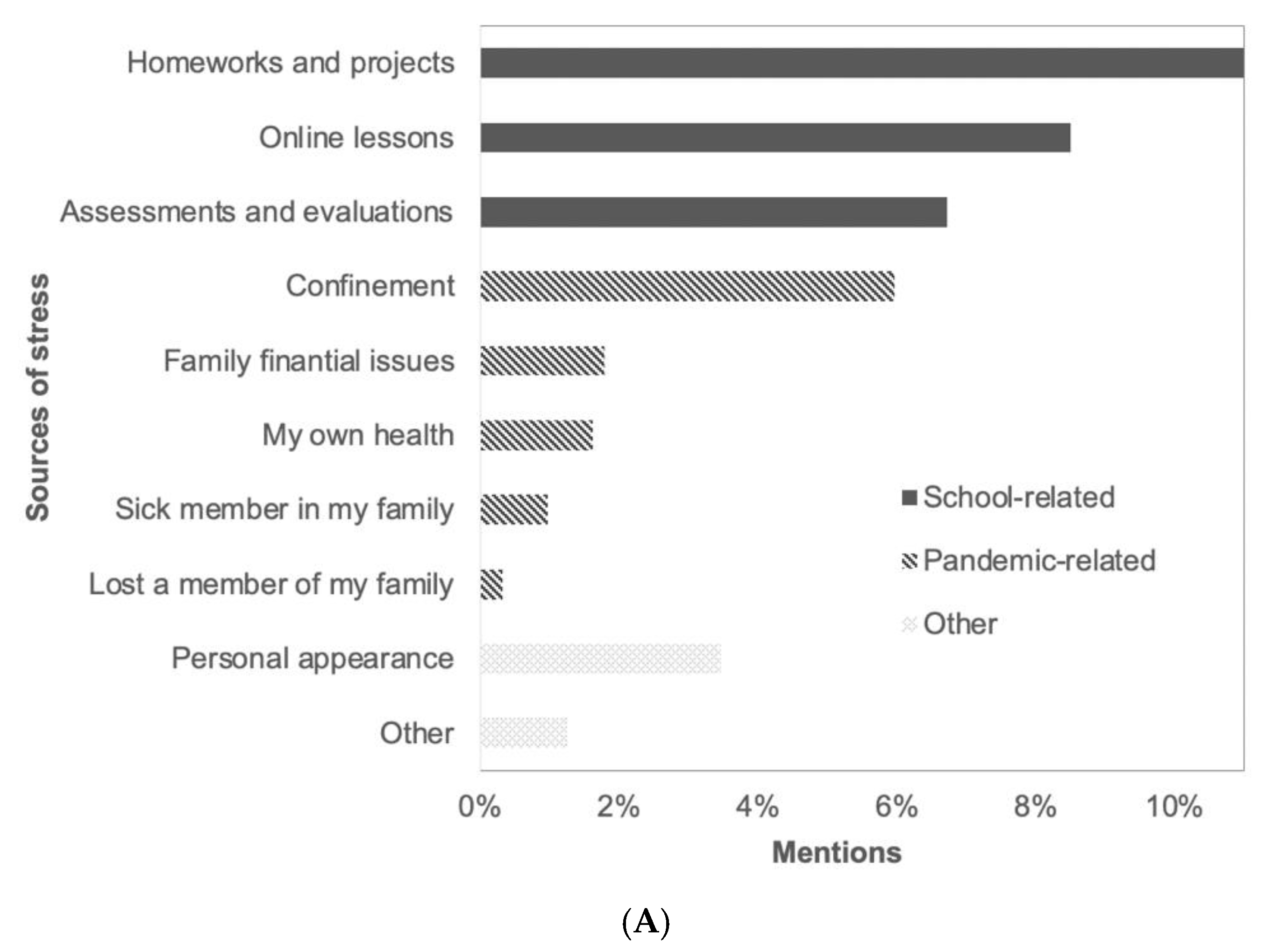

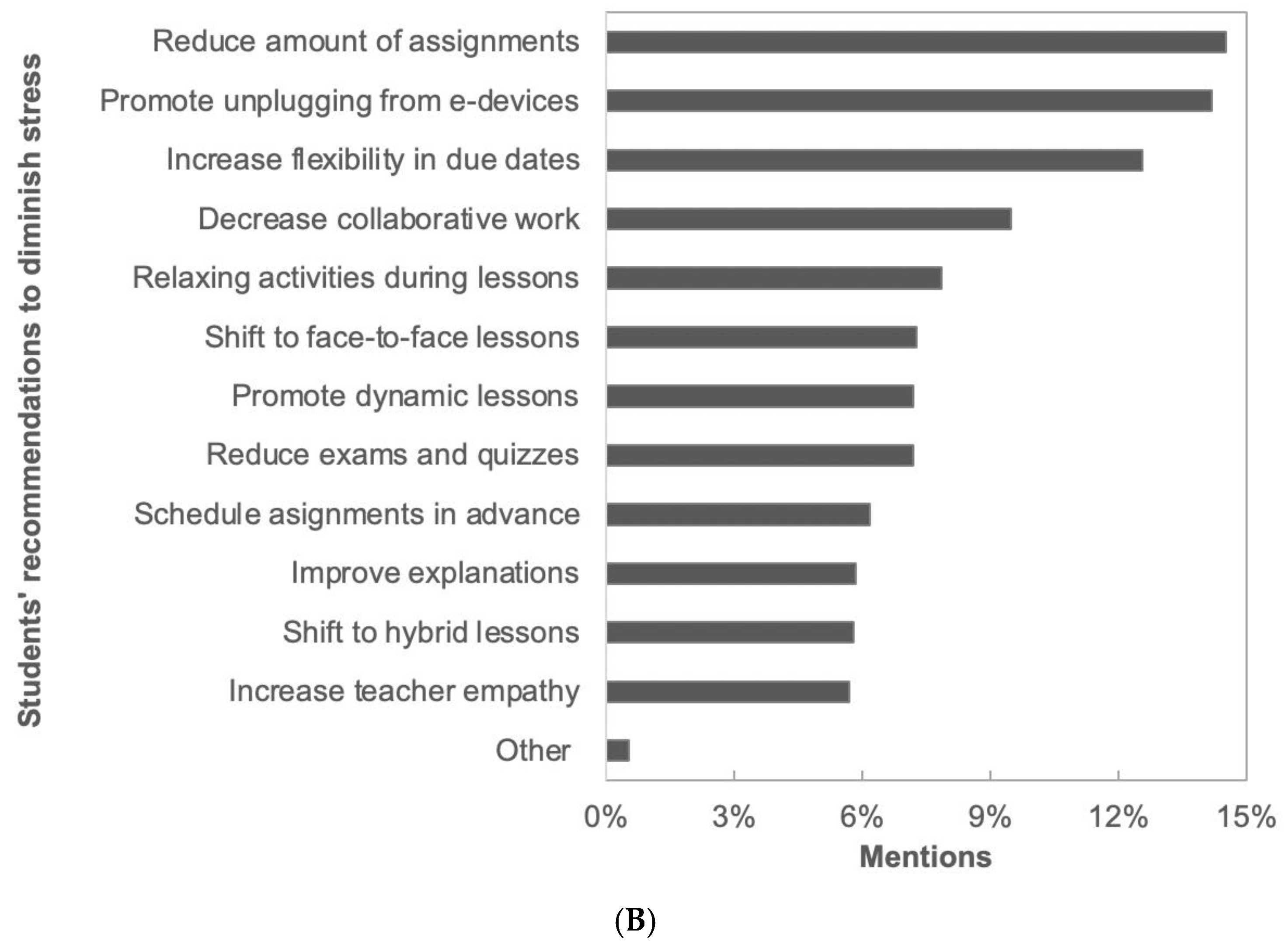

8. Results

9. Discussion

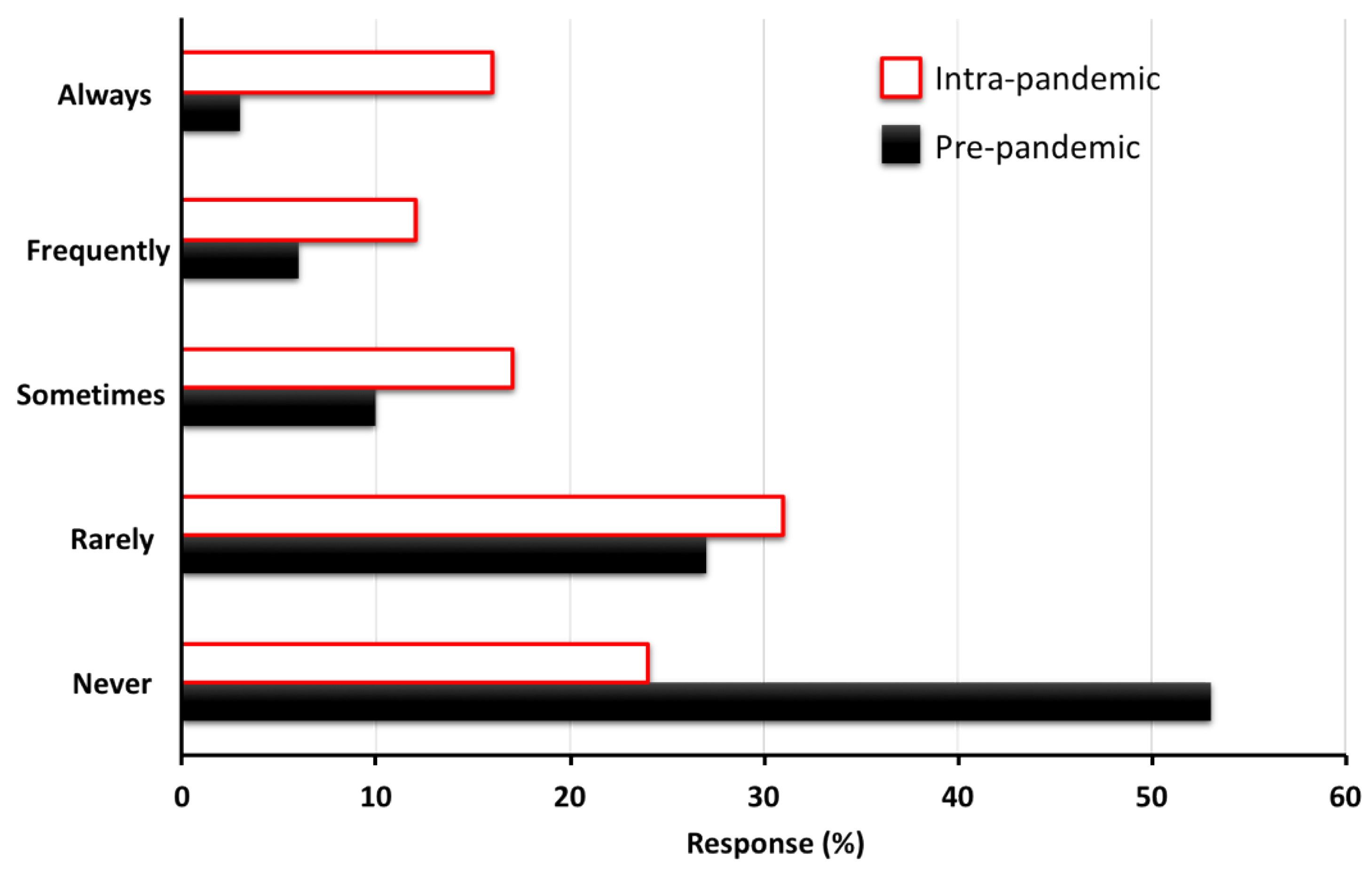

10. Insights on Adolescent Sleep during Quarantine and Implications for Future Crises Management

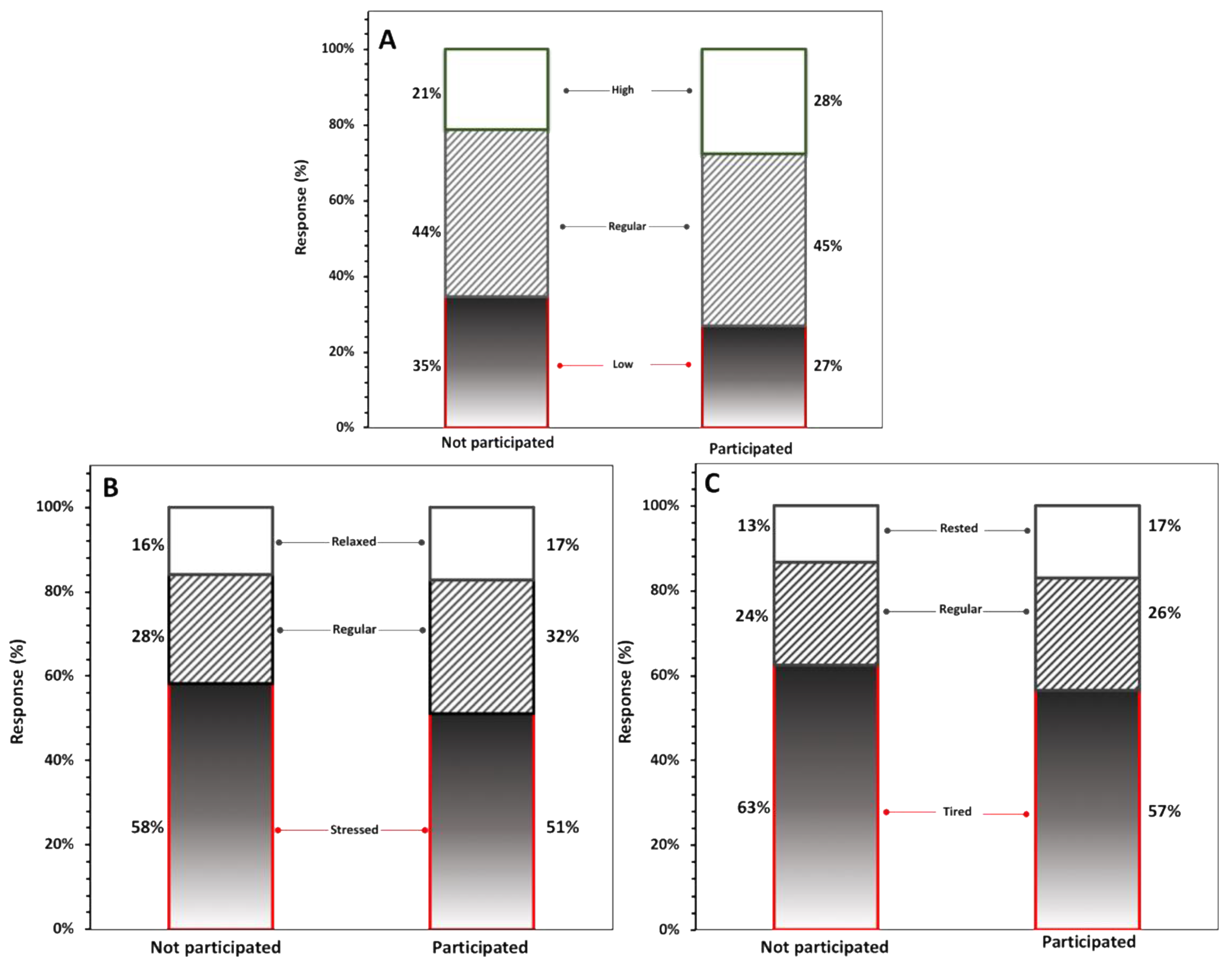

11. The Impact of COVID-19 Quarantine and Unplugged Day on Energy Level, Stress, and Tiredness

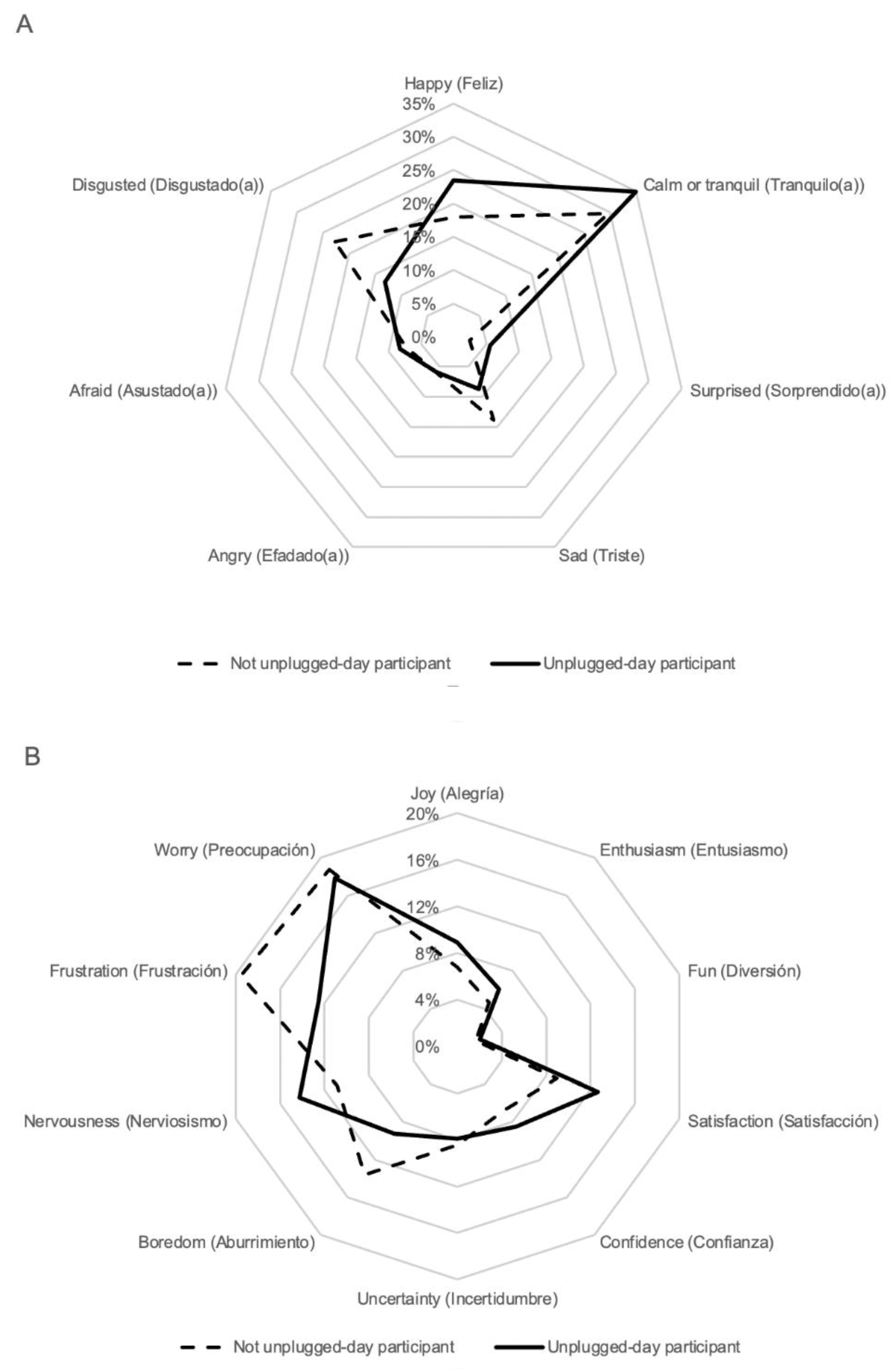

12. The Impact of COVID-19 Quarantine and Unplugged Day on Adolescents’ Emotions

13. The Urgent Need to Address Student Stress in the Online Learning Environments

14. Strategies for Safeguarding the Mental Well-Being of Young Students

15. Limitations and Future Directions

16. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Commission, E. Skills for Industry Curriculum Guidelines 4.0: Future-Proof Education and Training for Manufacturing in Europe: Final Report; EU Publications: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.H.; Sultana, M.S.; Hossain, S.; Hasan, M.T.; Ahmed, H.U.; Sikder, M.T. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health & Wellbeing among Home-Quarantined Bangladeshi Students: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odriozola-Gonzáles, P.; Planchuelo-Gómez, Á.; Jesús Irurtia, M.; de Luis-García, R. Psychological Effects of the COVID-19 Outbreak and Lockdown among Students and Workers of a Spanish University. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Roy, D.; Sinha, K.; Parveen, S.; Sharma, G.; Joshi, G. Impact of COVID-19 and Lockdown on Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: A Narrative Review with Recommendations. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Sun, J.; Feng, Y. How Have COVID-19 Isolation Policies Affected Young People’s Mental Health?—Evidence From Chinese College Students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Goldberg, S.B.; Lin, D.; Qiao, S.; Operario, D. Psychiatric Symptoms, Risk, and Protective Factors among University Students in Quarantine during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhai, A.; Yang, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, H.; Yang, C.; Duan, S.; Zhou, C. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms of High School Students in Shandong Province During the COVID-19 Epidemic. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 570096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. Education: From Disruption to Recovery. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/COVID-19/education-disruption-recovery (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Kaur, A.; Mittal, N.; Khosla, P.K.; Mittal, M. Machine Learning Tools to Predict the Impact of Quarantine. In Predictive and Preventive Measures for COVID-19 Pandemic. Algorithms for Intelligent Systems; Khosla, P.K., Mittal, M., Sharma, D., Goyal, L.M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and How to Reduce It: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salfi, F.; D’Atri, A.; Tempesta, D.; Ferrara, M. Sleeping under the Waves: A Longitudinal Study across the Contagion Peaks of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Lin, D.; Operario, D. Need for a Population Health Approach to Understand and Address Psychosocial Consequences of COVID-19. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Zuñiga, C.; Pego, L.; Escamilla, J.; Hosseini, S. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Students’ Feelings at High School, Undergraduate, and Postgraduate Levels. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, B.K. Children’s Screen Time During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Boundaries and Etiquette. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfin, D.R.; Silver, R.C.; Holman, E.A. The Novel Coronavirus (COVID-2019) Outbreak: Amplification of Public Health Consequences by Media Exposure. Health Psychol. 2020, 39, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, M. Technology-Mediated Learning Theory. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50, 1035–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubic, N.; Badovinac, S.; Johri, A.M. Student Mental Health in the Midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Call for Further Research and Immediate Solutions. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 517–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederer, A.M.; Hoban, M.T.; Lipson, S.K.; Zhou, S.; Eisenberg, D. More Than Inconvenienced: The Unique Needs of U.S. College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 48, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salfi, F.; Amicucci, G.; Corigliano, D.; D’Atri, A.; Viselli, L.; Tempesta, D.; Ferrara, M. Changes of Evening Exposure to Electronic Devices during the COVID-19 Lockdown Affect the Time Course of Sleep Disturbances. Sleep 2021, 44, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudland, J.R.; Golding, C.; Wilkinson, T.J. The Stress Paradox: How Stress Can Be Good for Learning. Med. Educ. 2020, 54, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.T.; Cao, J.; Li, T.M.H. Eustress or Distress: An Empirical Study of Perceived Stress in Everyday College Life. In Proceedings of the UbiComp 2016 Adjun: 2016 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing, Heidelberg, Germany, 12–16 September 2016; pp. 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, C.K.; Chaturvedi, S.; Chaturvedi, S. A Review on the Effectiveness of Current Approaches to Stress Management. Asian J. Pharm. Res. Dev. 2018, 6, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Health Organization Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020, WHO Librar.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Deighton, J.; Lereya, S.T.; Casey, P.; Patalay, P.; Humphrey, N.; Wolpert, M. Prevalence of Mental Health Problems in Schools: Poverty and Other Risk Factors among 28000 Adolescents in England. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 215, 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torales, J.; O’Higgins, M.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Ventriglio, A. The Outbreak of COVID-19 Coronavirus and Its Impact on Global Mental Health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.M.; Winsky, L.; Zehr, J.L.; Gordon, J.A. Priorities in Stress Research: A View from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health. Stress 2020, 24, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, C.; Hughes, J.L. Storm and Stress. In Encyclopedia of Adolescence; Levesque, R.J.R., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 2877–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, R.D. The Teenage Brain: The Stress Response and the Adolescent Brain. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, J.K.; Menon, K.; Thattil, A. Understanding Academic Stress among Adolescents. Artha-J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 16, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghatol, S.D. Academic Stress among Higher Secondary School Students: A Review. Int. J. Adv. Res. Educ. Technol. 2017, 4, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe, M.C.; Hetrick, S.E.; Parker, A.G. The Impact of Stress on Students in Secondary School and Higher Education. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2019, 25, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Gómez, M.G.; De la Roca-Chiapas, J.M.; Zavala-Bervena, A.; Rivera Cisneros, A.E.; Reyes Pérez, V.; Da Silva Rodrigues, C.; Novack, K. Stress in High School Students: A Descriptive Study. J. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Styck, K.M.; Malecki, C.K.; Ogg, J.; Demaray, M.K. Measuring COVID-19-Related Stress Among 4th Through 12th Grade Students. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 50, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. PISA 2015 Results (Volume III) Students’ Well-Being; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonam, K.D. A Study to Assess the Academic Stress and Coping Strategies among Adolescent Students: A Descriptive Study. Indian J. Appl. Res. 2019, 9, 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Subramani, C.; Kadhiravan, S. Academic Stress And Mental Health among High School Students. Indian J. Appl. Res. 2017, 7, 404–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, N.H.H.; Alavi, M.; Mehrinezhad, S.A.; Ahmadi, A. Academic Stress and Self-Regulation among University Students in Malaysia: Mediator Role of Mindfulness. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, U.; Shahnawaz, M.G.; Khan, N.H.; Kharshiing, K.D.; Khursheed, M.; Gupta, K.; Kashyap, D.; Uniyal, R. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Among Indians in Times of COVID-19 Lockdown. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 57, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalin, N.H. The Critical Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittchen, H.-U.; Hoyer, J.; Friis, R. Generalized Anxiety Disorder—A Risk Factor for Depression? Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2001, 10, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlaghi Jami, L.; Hassani-Abharian, P.; Ahadi, H.; Kakavand, A. Efficacy of Cognitive Rehabilitation Therapy on Stress and Anxiety of the High School Second Level Female Students. Adv. Cogn. Sci. 2020, 22, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, C.; Naylor, R.; Arkoudis, S. The First Year Experience in Australian Universities: Findings from Two Decades, 1994–2014; University of Melbourne, Centre for the Study of Higher Education: Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Amicucci, G.; Salfi, F.; D’atri, A.; Viselli, L.; Ferrara, M. The Differential Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Sleep Quality, Insomnia, Depression, Stress, and Anxiety among Late Adolescents and Elderly in Italy. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.; van Zeller, M.; Amorim, P.; Pimentel, A.; Dantas, P.; Eusébio, E.; Neves, A.; Pipa, J.; Santa Clara, E.; Santiago, T.; et al. Sleep Quality in Times of COVID-19 Pandemic. Sleep Med. 2020, 74, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viselli, L.; Salfi, F.; D’atri, A.; Amicucci, G.; Ferrara, M. Sleep Quality, Insomnia Symptoms, and Depressive Symptomatology among Italian University Students before and during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualano, M.R.; Lo Moro, G.; Voglino, G.; Bert, F.; Siliquini, R. Effects of COVID-19 Lockdown on Mental Health and Sleep Disturbances in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galván, A. The Need for Sleep in the Adolescent Brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020, 24, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.-J.; Wang, L.-L.; Yang, R.; Yang, X.-J.; Zhang, L.-G.; Guo, Z.-C.; Chen, J.-C.; Wang, J.-Q.; Chen, J.-X. Sleep Problems among Chinese Adolescents and Young Adults during the Coronavirus-2019 Pandemic. Sleep Med. 2020, 74, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, O.; Malorgio, E.; Doria, M.; Finotti, E.; Spruyt, K.; Melegari, M.G.; Villa, M.P.; Ferri, R. Changes in Sleep Patterns and Disturbances in Children and Adolescents in Italy during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Sleep Med. 2021, 91, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.P.; Dvorsky, M.R.; Breaux, R.; Cusick, C.N.; Taylor, K.P.; Langberg, J.M. Prospective Examination of Adolescent Sleep Patterns and Behaviors before and during COVID-19. Sleep 2021, 44, zsab054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, N.; MacGowan, R.L.; Gabriel, A.S.; Podsakoff, N.P. Unplugging or Staying Connected? Examining the Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences of Profiles of Daily Recovery Experiences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miksch, L.; Schulz, C. Disconnect to Reconnect: The Phenomenon of Digital Detox as a Reaction to Technology Overload. Lund University, 2018. Available online: http://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/record/8944615 (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Lisitsa, E.; Benjamin, K.S.; Chun, S.K.; Skalisky, J.; Hammond, L.E.; Mezulis, A.H. Loneliness Among Young Adults During COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediational Roles of Social Media Use and Social Support Seeking. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 39, 708–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Ho, S.; Olusanya, O.; Antonini, M.V.; Lyness, D. The Use of Social Media and Online Communications in Times of Pandemic COVID-19. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2020, 22, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdez, D.; ten Thij, M.; Bathina, K.; Rutter, L.A.; Bollen, J. Social Media Insights Into US Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal Analysis of Twitter Data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.R.; Murad, H.M. The Impact of Social Media on Panic During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Iraqi Kurdistan: Online Questionnaire Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killgore, W.D.S.; Cloonan, S.A.; Taylor, E.C.; Dailey, N.S. Loneliness: A Signature Mental Health Concern in the Era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.L.; Morse, B.L.; DeGraffenried, W.; McAuliffe, D.L. Addressing Stress in High School Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. NASN Sch. Nurse 2021, 36, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Hermida, A.P. College Students’ Use and Acceptance of Emergency Online Learning Due to COVID-19. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2020, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trust, T.; Whalen, J. Should Teachers Be Trained in Emergency Remote Teaching? Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2020, 28, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Pajarianto, H.; Kadir, A.; Galugu, N.; Sari, P.; Februanti, S. Study from Home in the Middle of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analysis of Religiosity, Teacher, and Parents Support Against Academic Stress. J. Talent Dev. Excell. 2020, 12, 1791–1807. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Chen, A.; Chen, Y. College Students’ Stress and Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Academic Workload, Separation from School, and Fears of Contagion. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Wright, E.P.; Dedding, C.; Pham, T.T.; Bunders, J. Low Self-Esteem and Its Association With Anxiety, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation in Vietnamese Secondary School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilsen, J. Suicide and Youth: Risk Factors. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, K.A.; Castleman, B.L.; Lohner, G. Negative Impacts From the Shift to Online Learning During the COVID-19 Crisis: Evidence From a Statewide Community College System. AERA Open 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczewski, M.; Gorbaniuk, O.; Giuri, P. The Psychological and Academic Effects of Studying From the Home and Host Country During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Swekwi, U.; Tu, C.C.; Dai, X. Psychological Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Wuhan’s High School Students. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, F.; Wei, C.; Jia, Y.; Shang, Z.; Sun, L.; Wu, L.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Prevalence and Predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 Outbreak in China Hardest-Hit Areas: Gender Differences Matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirahmadizadeh, A.; Ranjbar, K.; Shahriarirad, R.; Erfani, A.; Ghaem, H.; Jafari, K.; Rahimi, T. Evaluation of Students’ Attitude and Emotions towards the Sudden Closure of Schools during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.-J.; Zhang, L.-G.; Wang, L.-L.; Guo, Z.-C.; Wang, J.-Q.; Chen, J.-C.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.-X. Prevalence and Socio-Demographic Correlates of Psychological Health Problems in Chinese Adolescents during the Outbreak of COVID-19. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiran, S.; Sanjana, J.; Reddy, N. Mobile Phone Addiction: Symptoms, Impacts and Causes—A Review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Trends in Industrial & Value Engineering, Business and Social Innovation, Karnataka, India, 28–30 March 2019; pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, L.; Shao, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Miao, J.; Yang, X.; Zhu, G. An Investigation of Mental Health Status of Children and Adolescents in China during the Outbreak of COVID-19. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Mei, W.; Ugrin, J.C. Student Cyberloafing In and Out of the Classroom in China and the Relationship with Student Performance. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, J.C. Problematic Social Network Use: Its Antecedents and Impact upon Classroom Performance. Comput. Educ. 2022, 177, 104368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Sujan, M.S.H.; Tasnim, R.; Mohona, R.A.; Ferdous, M.Z.; Kamruzzaman, S.; Toma, T.Y.; Sakib, M.N.; Pinky, K.N.; Islam, M.R.; et al. Problematic Smartphone and Social Media Use Among Bangladeshi College and University Students Amid COVID-19: The Role of Psychological Well-Being and Pandemic Related Factors. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 647386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.A.; Valley, B.; Simecka, B.A. Mental Health Concerns in the Digital Age. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2017, 15, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, M.; Ahuja, P. Disconnect to Detox: A Study of Smartphone Addiction among Young Adults in India. Young Consum. 2020, 21, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.; Mittal, P.; Gupta, M.S.; Yadav, S.; Arora, A. Opinion of Students on Online Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa de Alda, J.A.G.; Marcos-Merino, J.M.; Méndez Gómez, F.J.; Mellado Jiménez, V.; Esteban, M.R. Emociones Académicas y Aprendizaje de Biología, Una Asociación Duradera. Enseñanza Cienc. 2019, 37, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.M.; Chen, F.S. Academic Stress Inventory of Students at Universities and Colleges of Technology. World Trans. Eng. Technol. Educ. 2009, 7, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Burde, D.; Kapit, A.; Wahl, R.L.; Guven, O.; Skarpeteig, M.I. Education in Emergencies: A Review of Theory and Research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 87, 619–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.K.; Williford, D.N.; Vaccaro, A.; Kisler, T.S.; Francis, A.; Newman, B. The Young and the Restless: Socializing Trumps Sleep, Fear of Missing out, and Technological Distractions in First-Year College Students. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2016, 22, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wing, Y.K.; Hao, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B. The Associations of Long-Time Mobile Phone Use with Sleep Disturbances and Mental Distress in Technical College Students: A Prospective Cohort Study. Sleep 2019, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sümen, A.; Evgin, D. Social Media Addiction in High School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study Examining Its Relationship with Sleep Quality and Psychological Problems. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 2265–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaarde, J.; Hoyt, L.T.; Ozer, E.J.; Maslowsky, J.; Deardorff, J.; Kyauk, C.K. So Much to Do Before I Sleep: Investigating Adolescent-Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Sleep. Youth Soc. 2018, 52, 592–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillen-O’Neel, C.; Huynh, V.W.; Fuligni, A.J. To Study or to Sleep? The Academic Costs of Extra Studying at the Expense of Sleep. Child Dev. 2013, 84, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altena, E.; Baglioni, C.; Espie, C.A.; Ellis, J.; Gavriloff, D.; Holzinger, B.; Schlarb, A.; Frase, L.; Jernelöv, S.; Riemann, D. Dealing with Sleep Problems during Home Confinement Due to the COVID-19 Outbreak: Practical Recommendations from a Task Force of the European CBT-I Academy. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 29, e13052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.P.; Gregory, A.M. Editorial Perspective: Perils and Promise for Child and Adolescent Sleep and Associated Psychopathology during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B.; Nanda Biswas, U.; Tan Mansukhani, R.; Vallejo Casarín, A.; Essau, C.A. The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Internet Use and Escapism in Adolescents. Rev. Psicol. Clínica Niños Adolesc. 2020, 7, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomée, S. Mobile Phone Use and Mental Health. A Review of the Research That Takes a Psychological Perspective on Exposure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Murayama, K.; Dehaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V. Motivational, Emotional, and Behavioral Correlates of Fear of Missing Out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, V. Why Do People Experience the Fear of Missing Out (FoMO)? Exposing the Link Between the Self and the FoMO Through Self-Construal. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 2019, 50, 524–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milyavskaya, M.; Saffran, M.; Hope, N.; Koestner, R. Fear of Missing out: Prevalence, Dynamics, and Consequences of Experiencing FOMO. Motiv. Emot. 2018, 42, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheever, N.A.; Rosen, L.D.; Carrier, L.M.; Chavez, A. Out of Sight Is Not out of Mind: The Impact of Restricting Wireless Mobile Device Use on Anxiety Levels among Low, Moderate and High Users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, R.B.; Leshner, G.; Almond, A. The Extended ISelf: The Impact of IPhone Separation on Cognition, Emotion, and Physiology. J. Comput. Commun. 2015, 20, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, S.; Merchant, R.M.; Lurie, N. The Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19 and Physical Distancing: The Need for Prevention and Early Intervention. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fu, P.; Fan, C.; Zhu, M.; Li, M. COVID-19 Stress and Mental Health of Students in Locked-Down Colleges. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasi, M.; Toro, F.; Arnò, S.; Carrieri, A.; Conte, M.M.; Devastato, M.D.; Picconi, L.; Sergi, M.R.; Saggino, A. Physical and Psychological Impact of the Phase One Lockdown for COVID-19 on Italians. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 563722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietromonaco, P.R.; Collins, N.L. Interpersonal Mechanisms Linking Close Relationships to Health. Am. Psychol. 2017, 72, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.M.; Chen, P.C.; Law, K.M.Y.; Wu, C.H.; Lau, Y.-Y.; Guan, J.; He, D.; Ho, G.T.S. Comparative Analysis of Student’s Live Online Learning Readiness during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic in the Higher Education Sector. Comput. Educ. 2021, 168, 104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, P.; Jia, Y.; Chen, H.; Mao, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Fu, H.; Dai, J. Mental Health Problems and Social Media Exposure during COVID-19 Outbreak. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, H.; Lyyra, N.; Hietajärvi, L.; Villberg, J.; Paakkari, L. Profiles of Internet Use and Health in Adolescence: A Person-Oriented Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durak, H.Y. Modeling of Variables Related to Problematic Internet Usage and Problematic Social Media Usage in Adolescents. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 39, 1375–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleel, M. Technology Addiction Among Students. Psychol. Educ. J. 2021, 58, 3646–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.C.; Wu, L.H.; Lam, H.Y.; Lam, L.K.; Nip, P.Y.; Ng, C.M.; Leung, K.C.; Leung, S.F. The Relationships between Mobile Phone Use and Depressive Symptoms, Bodily Pain, and Daytime Sleepiness in Hong Kong Secondary School Students. Addict. Behav. 2020, 101, 105975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bulck, J. Television Viewing, Computer Game Playing, and Internet Use and Self-Reported Time to Bed and Time out of Bed in Secondary-School Children. Sleep 2004, 27, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Z.-Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Jia, C.-X. Prolonged Mobile Phone Use Is Associated with Poor Academic Performance in Adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Tao, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, K.; Yang, Y.; Hao, J.; Tao, F. Impact of Screen Time on Mental Health Problems Progression in Youth: A 1-Year Follow-up Study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, G.; Wille, M.; Hemels, M.E. Short- and Long-Term Health Consequences of Sleep Disruption. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2017, 9, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surat, S.; Govindaraj, Y.D.; Ramli, S.; Yusop, Y.M.; Surat, S.; Govindaraj, Y.D.; Ramli, S.; Yusop, Y.M. An Educational Study on Gadget Addiction and Mental Health among Gen Z. Creat. Educ. 2021, 12, 1469–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, T. The Changes in the Effects of Social Media Use of Cypriots Due to COVID-19 Pandemic. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Billieux, J.; Potenza, M.N. Problematic Online Gaming and the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 9, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Blasi, M.; Giardina, A.; Giordano, C.; Coco, G.L.; Tosto, C.; Billieux, J.; Schimmenti, A. Problematic Video Game Use as an Emotional Coping Strategy: Evidence from a Sample of MMORPG Gamers. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, K.D.; Thompson, R.R. Preparing for the Aftermath of COVID-19: Shifting Risk and Downstream Health Consequences. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S31–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, R.A.; Jobe, M.C.; Ahmed, O.; Sharker, T. Mental Health Status, Anxiety, and Depression Levels of Bangladeshi University Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 20, 1500–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Yang, T.; Hall, D.L.; Jiao, G.; Huang, L.; Jiao, C. COVID-19 Uncertainty and Sleep: The Roles of Perceived Stress and Intolerance of Uncertainty during the Early Stage of the COVID-19 Outbreak. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic on College Students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A.; Hone, K.; Liu, X.; Tarhini, T. Examining the Moderating Effect of Individual-Level Cultural Values on Users’ Acceptance of E-Learning in Developing Countries: A Structural Equation Modeling of an Extended Technology Acceptance Model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2016, 25, 306–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, P.; Gabriel, A.; Merians, A.; Lust, K. Understanding Stress as an Impediment to Academic Performance. J. Am. Coll. Health 2018, 67, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaeta, M.L.; Gaeta, L.; Rodriguez, M.d.S. The Impact of COVID-19 Home Confinement on Mexican University Students: Emotions, Coping Strategies, and Self-Regulated Learning. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 642823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, A.; Starkey, L.; Egerton, B.; Flueggen, F. High School Students’ Experience of Online Learning during COVID-19: The Influence of Technology and Pedagogy. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2021, 30, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, R. Lifestyle and Mental Health. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcaraz, K.I.; Eddens, K.S.; Blase, J.L.; Diver, W.R.; Patel, A.V.; Teras, L.R.; Stevens, V.L.; Jacobs, E.J.; Gapstur, S.M. Social Isolation and Mortality in US Black and White Men and Women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llosa, J.A.; Menéndez-Espina, S.; Agulló-Tomás, E.; Rodríguez-Suárez, J. Job Insecurity and Mental Health: A Meta-Analytical Review of the Consequences of Precarious Work in Clinical Disorders. An. Psicol. 2018, 34, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez-Espina, S.; Llosa, J.A.; Agulló-Tomás, E.; Rodríguez-Suárez, J.; Sáiz-Villar, R.; Lahseras-Díez, H.F. Job Insecurity and Mental Health: The Moderating Role of Coping Strategies from a Gender Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.; Lund, C.; Kakuma, R. The Measurement of Poverty in Psychiatric Epidemiology in LMICs: Critical Review and Recommendations. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 1499–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, E.; Vonkeman, C.; Hartmann, T. Mood as a Resource in Dealing with Health Recommendations: How Mood Affects Information Processing and Acceptance of Quit-Smoking Messages. Psychol. Health 2011, 27, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubad, M.; Winsper, C.; Meyer, C.; Livanou, M.; Marwaha, S. A Systematic Review of the Psychometric Properties, Usability and Clinical Impacts of Mobile Mood-Monitoring Applications in Young People. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, A.; Ferris, D.; Gonçalves, B.; Quinn, N. What Has Economics Got to Do with It? The Impact of Socioeconomic Factors on Mental Health and the Case for Collective Action. Palgrave Commun. 2018, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, S.P.; Younas, A.; Sundus, A. Self-Awareness in Nursing: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Week | Number of Respondents |

|---|---|

| W1 | 176 |

| W2 | 193 |

| W3 | 166 |

| W4 | 152 |

| W5 | 113 |

| W6 | 160 |

| W7 | 245 |

| W8 | 125 |

| W9 | 198 |

| W10 | 177 |

| W11 | 140 |

| Total | 1845 |

| Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unplugged Day Participation | Year in High School | Female | Male | Sum |

| Partially unplugged from electronic devices | 1 | 390 | 183 | 573 |

| 2 | 177 | 86 | 263 | |

| 3 | 194 | 92 | 286 | |

| Entirely unplugged from electronic devices | 1 | 106 | 66 | 172 |

| 2 | 63 | 39 | 102 | |

| 3 | 45 | 36 | 81 | |

| No participation | 1 | 99 | 73 | 172 |

| 2 | 58 | 39 | 97 | |

| 3 | 51 | 48 | 99 | |

| Sum | 1183 | 662 | 1845 | |

| # | Question | Options |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | What was your energy level this week? | Very low, low, neutral, high, very high |

| Q2 | Which of the following phrases do you identify with the most? This week I felt… | Very stressed, stressed, neither stressed nor relaxed, relaxed, very relaxed |

| Q2.1 | Which of the following situations made you feel stressed during the week? | Homework and assignments, grades, confinement, virtual classes, infection of relatives, familiar finances, familiar relationships, my relationship, personal appearance, death of a relative, my health, other |

| Q2.2 | What do you think Tec de Monterrey could do to reduce your stress? Please select those options that best apply for you. | Dynamic teaching, better class explanations, less collaborative work, less homework, flexibility in deadlines, class activities focused on relaxation, empathetic teachers, planned activities, fewer mid-term exams, fewer quizzes, more unplugging, hybrid classes, face-to-face classes, is not a university problem, other |

| Q3 | Which of the following phrases do you identify with the most? This week I felt… | Very tired, tired, neither tired nor rested, rested, very rested |

| Q4 | Based on the following list of emotions, which of them did you experience most frequently this week? | Tranquil, happy, upset, sad, scared, surprised, angry, other |

| Q5 | Based on the emotion you experienced during the week, do you think you need any help to manage it? (only for those respondents who experienced negative emotions) | Yes, No |

| Q6 | Have you experienced insomnia in the last week (issues to fall asleep)? | Yes, all weekdays; yes, almost all weekdays (5–6 days); Yes, some days during the week (3–4 days); yes just a few days during the week (1–2 days); no, I have not experienced insomnia during the week |

| Q7 | Had you experienced insomnia before the COVID-19 pandemic? | Yes, all weekdays; yes, almost all weekdays (5–6 days); Yes, some days during the week (3–4 days); yes just a few days during the week (1–2 days); no, I have not experienced insomnia during the week |

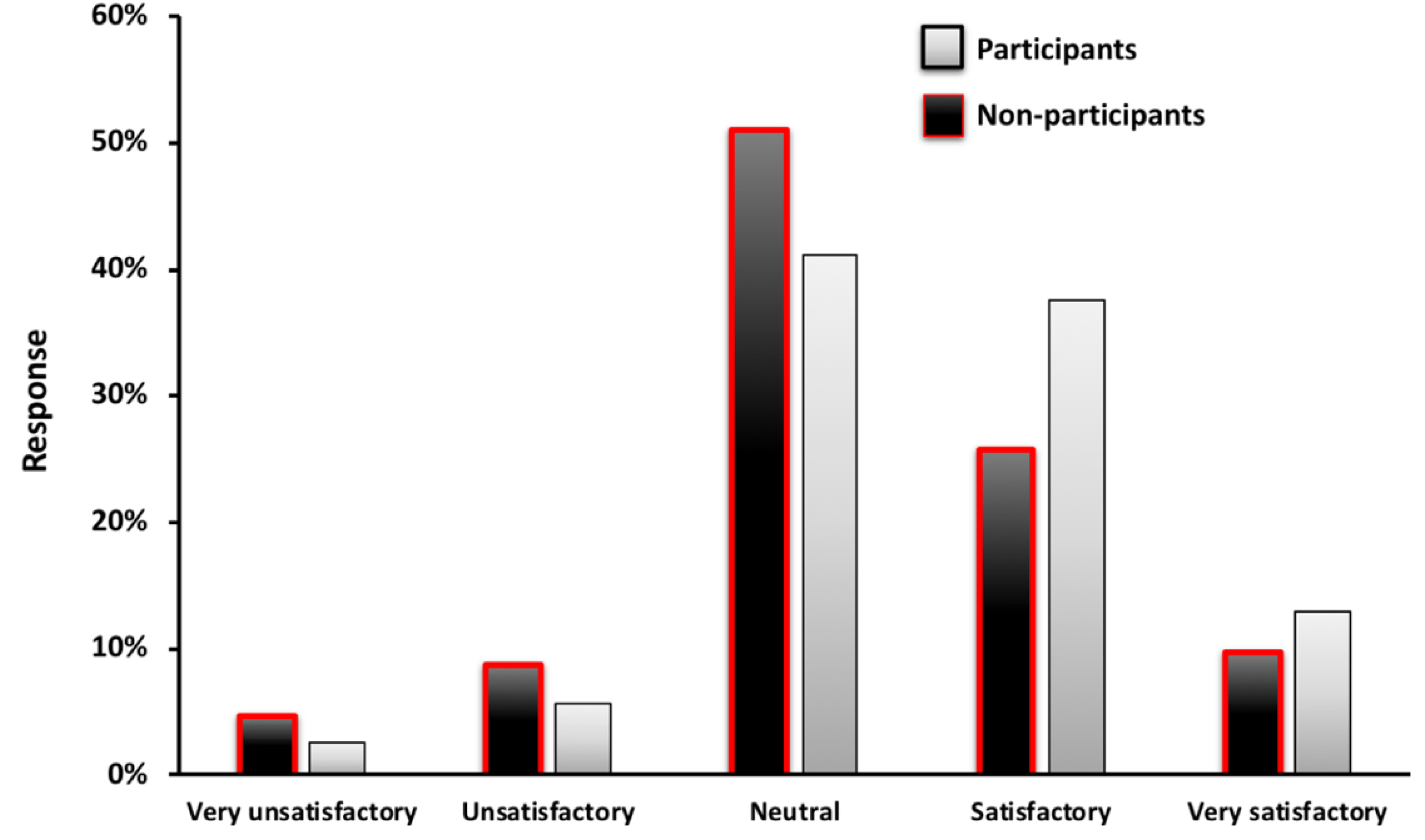

| Q8 | How was your experience with online classes this week? | Very unsatisfactory, unsatisfactory, neutral, satisfactory, very satisfactory |

| Q9 | Thinking about your academic experience during this week, what was the emotion you felt most frequently? | Worry, frustration, nervousness, satisfaction, boredom, joy/, confidence, uncertainty, enthusiasm, fun |

| Q10 | Have you participated in “Unplugged day” activities? | Yes, no |

| Q11 | Did you completely unplug from your electronic devices? (only for those respondents that did participate in “Unplugged day”) | Yes, no |

| Variable | χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of energy | 330.27 | 0.0000 | *** |

| Tiredness | 278.44 | 0.0000 | *** |

| Stress | 161.56 | 0.0000 | *** |

| Insomnia before lockdown | 535.74 | 0.0000 | *** |

| General dominant emotion | 216.12 | 0.0000 | *** |

| Positive/negative emotions with/without the need for professional help | 183.69 | 0.0000 | *** |

| School-related emotion | 249.08 | 0.0000 | *** |

| Online education experience | 128.94 | 0.0000 | *** |

| Non-Unplugged Day Participants | Unplugged Day Participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive emotions | 184 (50%) | 945 (64%) |

| No professional help needed to deal with negative emotions | 158 (43%) | 455 (31%) |

| Professional help needed to deal with negative emotions | 26 (7%) | 77 (5%) |

| Variable | χ2 | p | Dependency on Participation in Unplugged Day | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most frequent emotion | 53.14 | 0.0000 | *** | Not independent |

| Psychological help needed | 31.74 | 0.0000 | *** | Not independent |

| Perception of online education | 36.98 | 0.0000 | *** | Not independent |

| Gender | 18.20 | 0.0001 | *** | Not independent |

| Level of energy | 28.79 | 0.0003 | *** | Not independent |

| Tiredness | 28.56 | 0.0004 | *** | Not independent |

| Academic emotion | 42.19 | 0.0010 | ** | Not independent |

| Insomnia during lockdown | 23.47 | 0.0028 | ** | Not independent |

| Anxiety | 10.45 | 0.0107 | * | Not independent |

| Stress | 16.89 | 0.0132 | * | Not independent |

| Academic Year | 5.77 | 0.2166 | Inconclusive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hosseini, S.; Camacho, C.; Donjuan, K.; Pego, L.; Escamilla, J. Unplugging for Student Success: Examining the Benefits of Disconnecting from Technology during COVID-19 Education for Emergency Planning. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050446

Hosseini S, Camacho C, Donjuan K, Pego L, Escamilla J. Unplugging for Student Success: Examining the Benefits of Disconnecting from Technology during COVID-19 Education for Emergency Planning. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(5):446. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050446

Chicago/Turabian StyleHosseini, Samira, Claudia Camacho, Katia Donjuan, Luis Pego, and Jose Escamilla. 2023. "Unplugging for Student Success: Examining the Benefits of Disconnecting from Technology during COVID-19 Education for Emergency Planning" Education Sciences 13, no. 5: 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050446

APA StyleHosseini, S., Camacho, C., Donjuan, K., Pego, L., & Escamilla, J. (2023). Unplugging for Student Success: Examining the Benefits of Disconnecting from Technology during COVID-19 Education for Emergency Planning. Education Sciences, 13(5), 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050446