Exploring the Role of Mind Mapping Tools in Scaffolding Narrative Writing in English for Middle-School EFL Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Writing Instruction for Foreign Language Learners

2.1. Scaffolded Writing Instruction

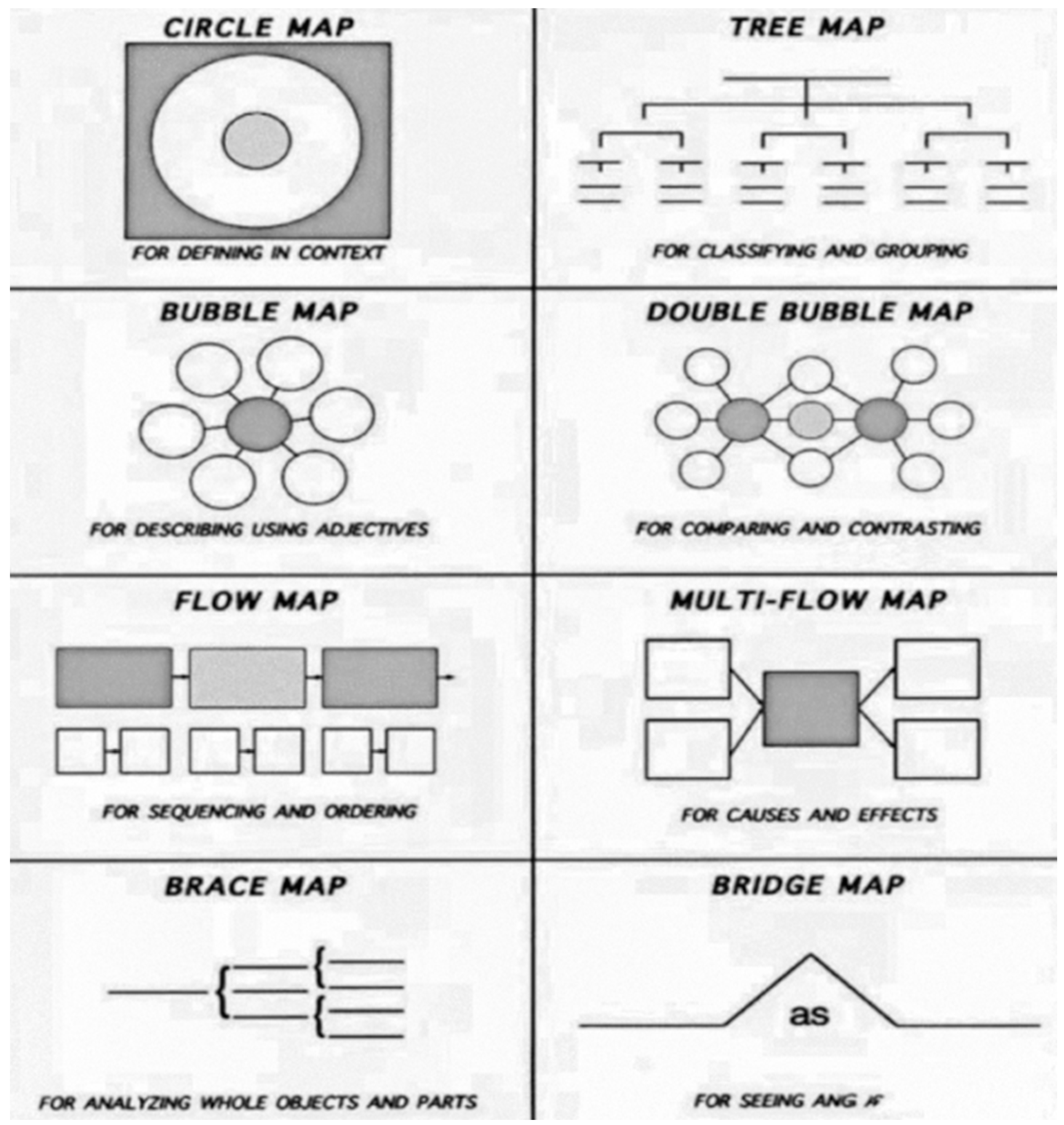

2.2. Mind Mapping as a Scaffold in Writing Instruction

2.3. Assessing English Writing Proficiency through the CAF Framework

3. The Current Study

4. Methods

4.1. Participants

4.2. School Context

4.3. Research Design and Procedures

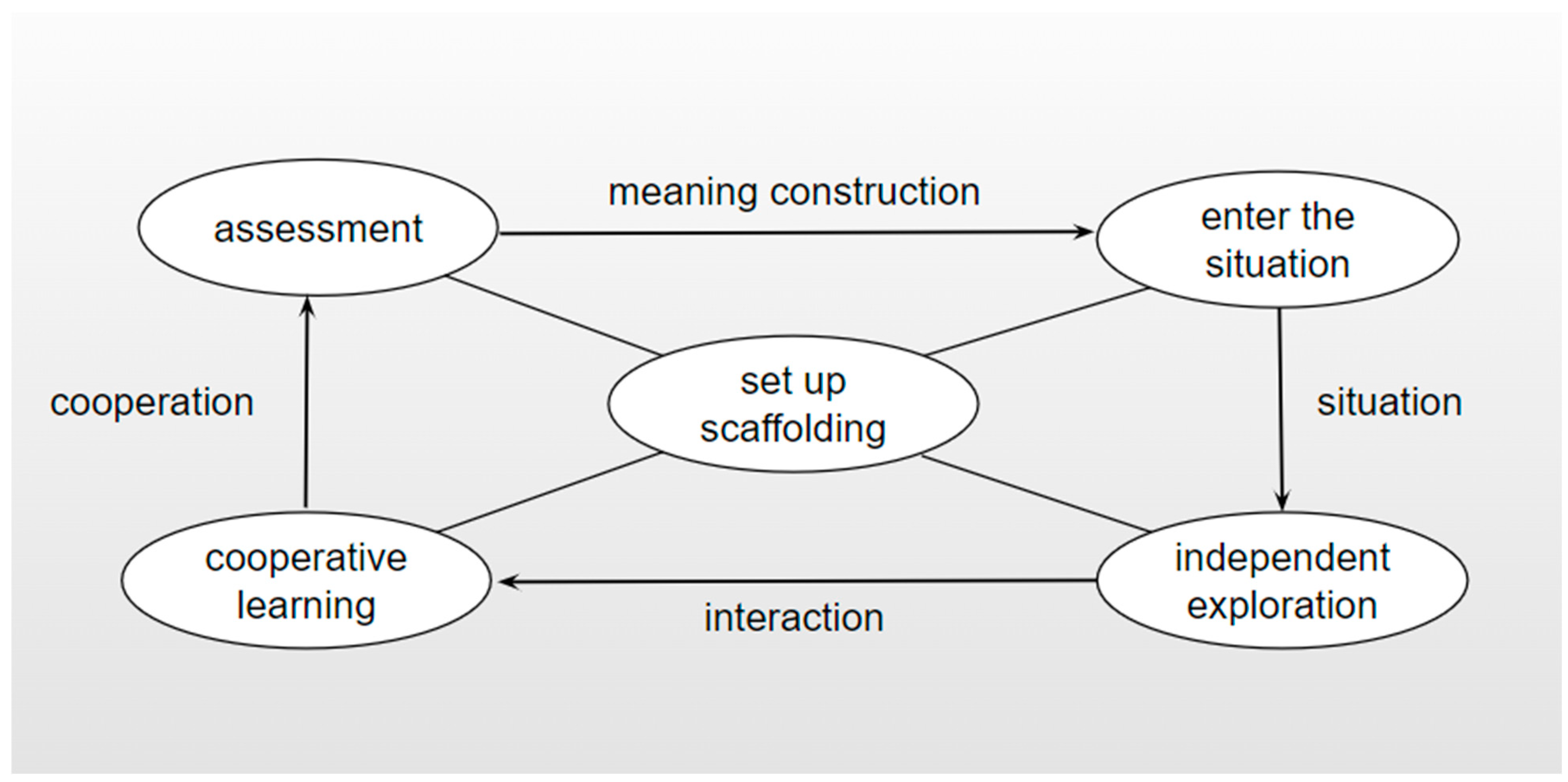

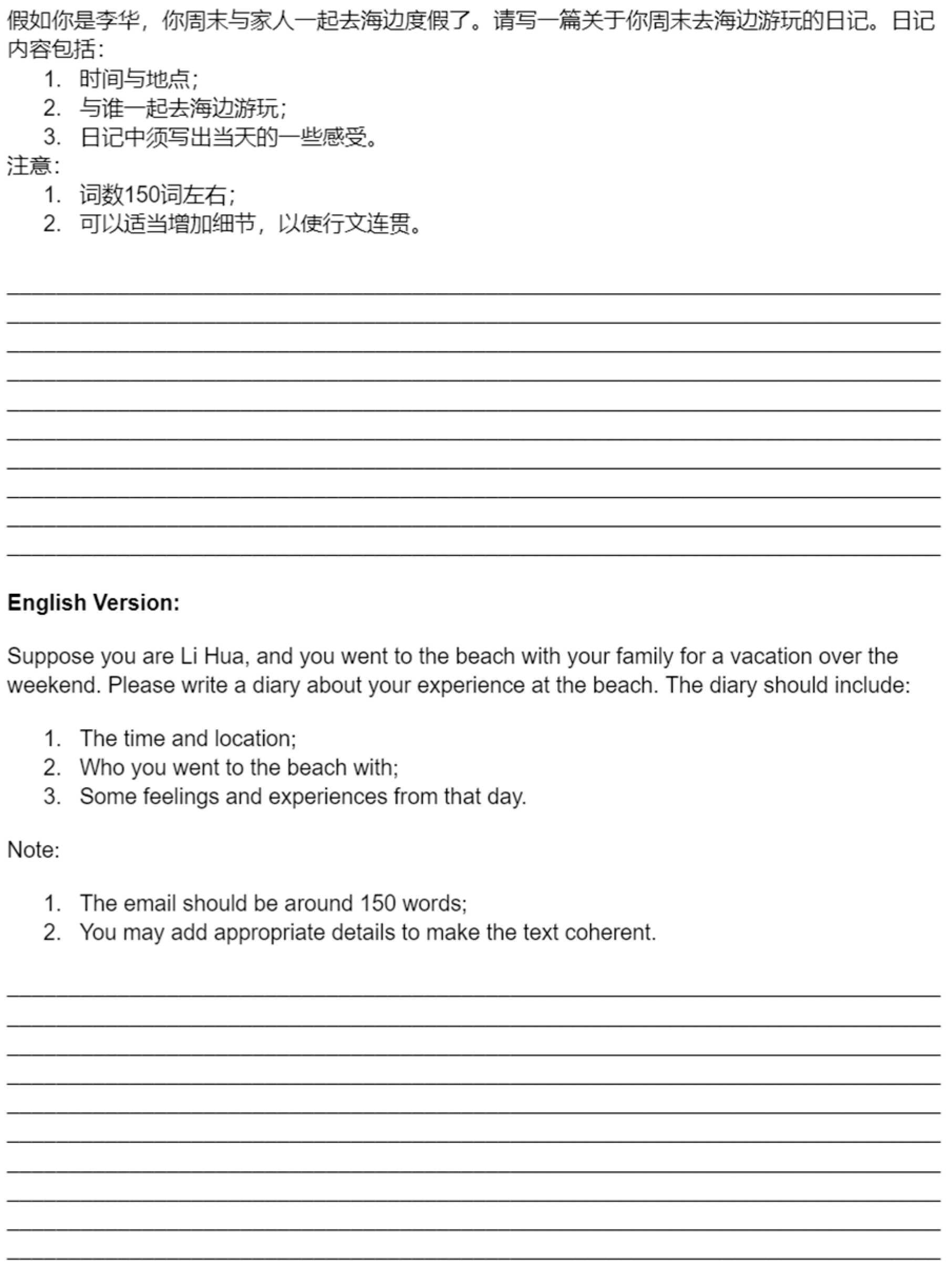

4.4. Intervention in the Treatment Classroom

4.5. Teacher–Researcher Collaborative Planning

4.6. Measures

4.7. Measurement of Lexical Complexity

4.8. Measurement of Grammatical Complexity

4.9. Measurement of Linguistic Accuracy

4.10. Measurement of Fluency

4.11. Data Analysis

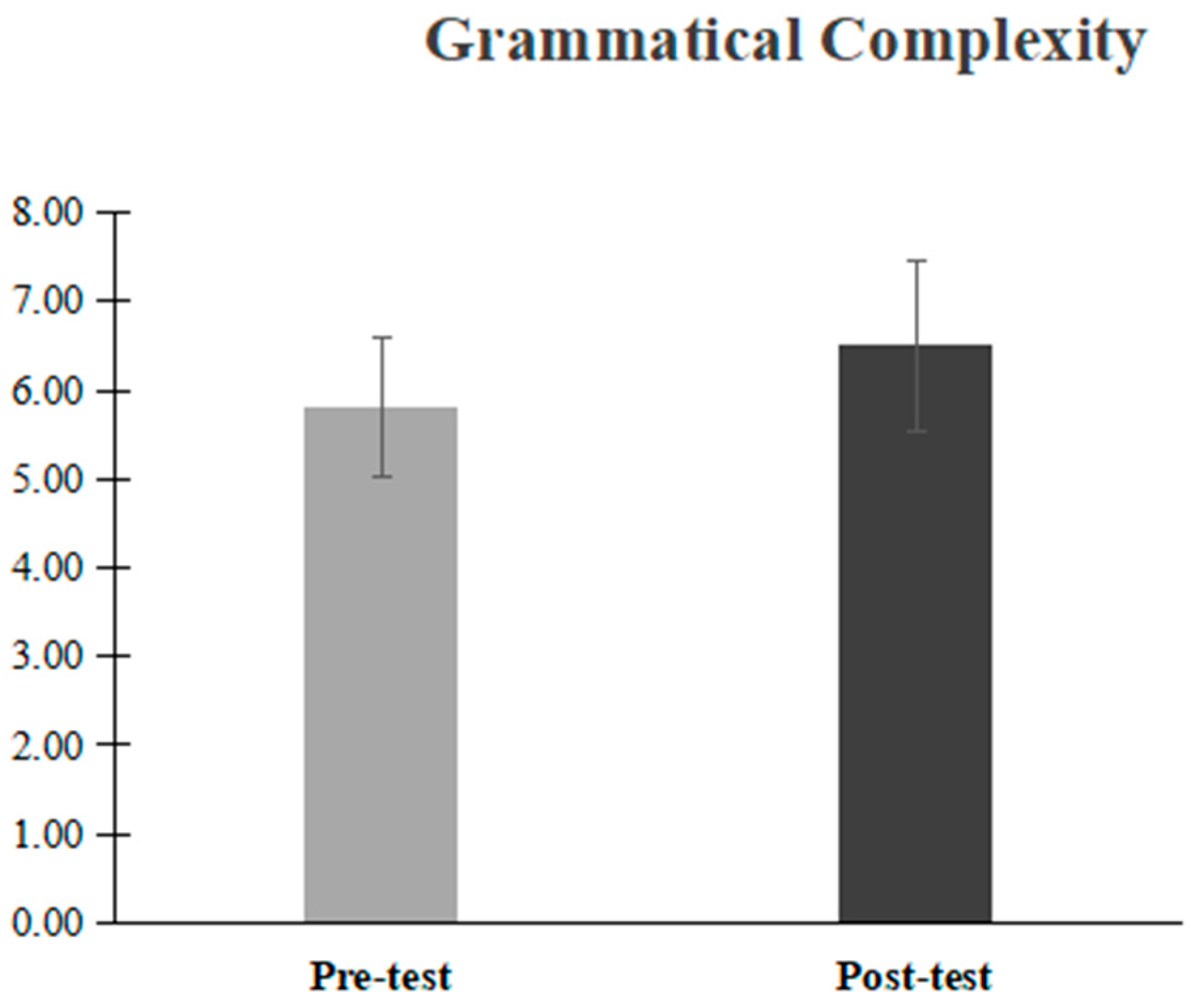

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Lexical Complexity

6.2. Grammatical Complexity

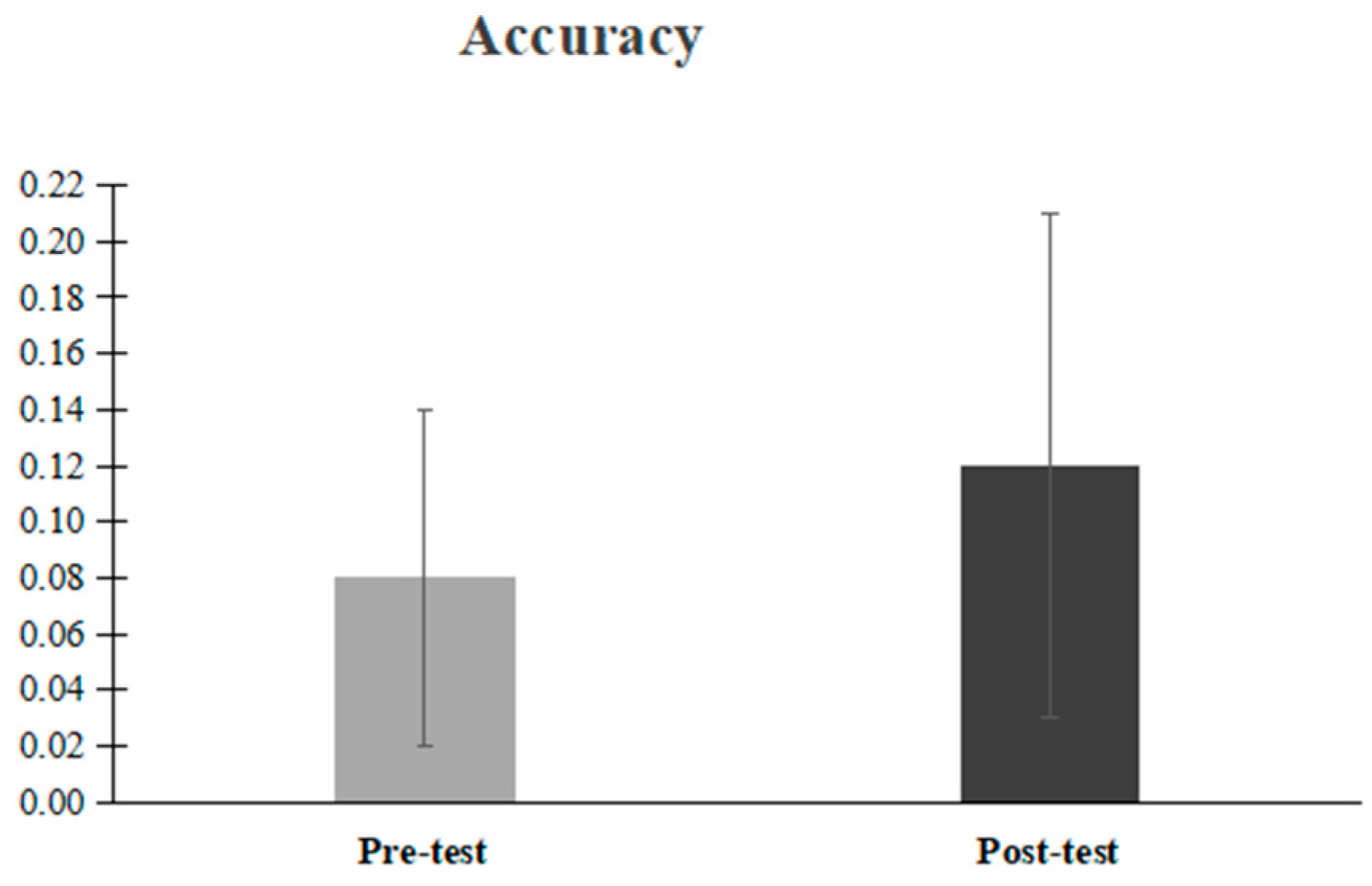

6.3. Linguistic Accuracy

6.4. Fluency

6.5. Significance of Findings

6.6. Implications

6.7. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grabe, W.; Kaplan, R.B. Theory and Practice of Writing: An Applied Linguistic Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, C.M.; Ransdell, S. (Eds.) The Science of Writing: Theories, Methods, Individual Differences and Applications; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-S.G.; Graham, S. Expanding the Direct and Indirect Effects Model of Writing (DIEW): Reading–writing relations, and dynamic relations as a function of measurement/dimensions of written composition. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 114, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, C.A.; Graham, S. Writing research from a cognitive perspective. In Handbook of Writing Research, 2nd ed.; MacArthur, C.A., Graham, S., Fitzgerald, J., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Olive, T.; Kellogg, R.T. Concurrent activation of high-and low-level production processes in written composition. Mem. Cogn. 2002, 30, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrance, M.; Jeffery, G.C. The Cognitive Demands of Writing: Processing Capacity and Working Memory Effects in Text Production; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 6, pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, C.H.; Cheung, Y.L. Mediation in a socio-cognitive approach to writing for elementary students: Instructional scaffolding. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmadewi, N.N.; Artini, L.P. Using scaffolding strategies in teaching writing for improving student literacy in primary school. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Innovation in Education (ICoIE 2018), Bali, Indonesia, 29–30 September 2018; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2019; pp. 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, H.C.; Chen, C.M.; Tsai, Y.H.; Lee, B.O.; Dewi, Y.S. Is instructional scaffolding a better strategy for teaching writing to EFL learners? A functional MRI study in healthy young adults. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.H.; Alrabah, S. Instructional scaffolding strategies to support the L2 writing of EFL college students in Kuwait. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2023, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Walqui, A. Scaffolding instruction for English language learners: A conceptual framework. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2006, 9, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.Y.; Chen, H.S.; Shadiev, R.; Huang, R.Y.M.; Chen, C.Y. Improving English as a foreign language writing in elementary schools using mobile devices in familiar situational contexts. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2014, 27, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, M.; Chu, S.; Ho, A.; Li, X. Using a wiki to scaffold primary-school students’ collaborative writing. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2011, 14, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Short, D.; Fitzsimmons, S. Double the Work: Challenges and Solutions to Acquiring Language and Academic Literacy for Adolescent English Language Learners; Alliance for Excellent Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wangmo, K. The Use of Mind Mapping Technique to Enhance Descriptive Writing Skills of Grade four Bhutanese Students. Ph.D. Dissertation, Rangsit University, Pathumthani, Thailand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zyoud, A.A.; Al Jamal, D.; Baniabdelrahman, A. Mind mapping and student’ writing performance. Arab. World Engl. J. 2017, 8, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.H.; Naqeeb, H. Does mind mapping technique improve cohesion and coherence in composition writing? An experimental study. Pak. J. Educ. 2020, 37, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarin, S.; Yawiloeng, R. Learning to write through mind mapping techniques in an EFL writing classroom. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2023, 13, 2490–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.M.; Chien, C.H. The use of mind mapping strategy in Malaysian university English test (MUET) Writing. Creat. Educ. 2016, 7, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmanson, J.; Kennett, K.; Magnifico, A.; McCarthey, S.; Searsmith, D.; Cope, B.; Kalantzis, M. Visualizing revision: Leveraging student-generated between-draft diagramming data in support of academic writing development. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2016, 21, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.K.; Lin, C.J.; Hwang, G.J.; Zhang, L. Impacts of a mind mapping-based contextual gaming approach on EFL students’ writing performance, learning perceptions and generative uses in an English course. Comput. Educ. 2019, 137, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saed, H.A.; Al-Omari, H.A. The effectiveness of a proposed program based on a mind mapping strategy in developing the writing achievement of eleventh grade EFL students in Jordan and their attitudes towards writing. J. Educ. Pract. 2014, 5, 88–110. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, H.; Sidekli, S. Developing story writing skills with fourth grade students’ mind mapping method. Egitim Bilim 2020, 45, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayavalsalan, B. Mind mapping as a strategy for enhancing essay writing skills. New Educ. Rev. 2016, 45, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Funes, M. Exploring the potential of second/foreign language writing for language learning: The effects of task factors and learner variables. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2015, 28, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Naqbi, S. The Use of Mind Mapping to Develop Writing Skills in UAE Schools. Educ. Bus. Soc. Contemp. Middle East. Issues 2011, 4, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.F.; Zhang, L.J. Development of children’s metacognitive knowledge, reading, and writing in English as a foreign language: Evidence from longitudinal data using multilevel models. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 91, 1202–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.F. Automatic scaffolding and measurement of concept mapping for EFL students to write summaries. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2015, 18, 273–286. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I. EFL writing in schools. In Handbook of Second and Foreign Language Writing; Manchón, R.M., Matsuda, P.K., Eds.; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwiers, J. Building Academic Language: Essential Practices for Content Classrooms, Grades 5–12; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, S.; Perin, D. A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 445–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nik, Y.A.; Hamzah, A.; Rafidee, H. A comparative study on the factors affecting the writing performance among Bachelor students. Int. J. Educ. Res. Technol. 2010, 1, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Reiser, B.J.; Tabak, I. Scaffolding. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, 2nd ed.; Sawyer, R.K., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, J. (Ed.) Scaffolding: A Focus on Teaching and Learning in Literacy Education; Primary English Teaching Association: Newtown, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, P. Scaffolding Language, Scaffolding Learning; Heinemann: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, S.A. An effective framework for primary-grade guided writing instruction. Read. Teach. 2008, 62, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintani, N. The roles of explicit instruction and guided practice in the proceduralization of a complex grammatical structure. In Doing SLA Research with Implications for the Classroom: Reconciling Methodological Demands and Pedagogical Applicability; Ed. Nassaji, H., Fotos, S., Eds.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Benko, S.L. Scaffolding: An ongoing process to support adolescent writing development. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 2012, 56, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggs, J.A. Effects of teacher-scaffolded and self-scaffolded corrective feedback compared to direct corrective feedback on grammatical accuracy in English L2 writing. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2019, 46, 100671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K.; Hyland, F. Feedback on second language students’ writing. Lang. Teach. 2006, 39, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, A.K.A. Scaffolding EFL students’ writing through the writing process approach. J. Educ. Pract. 2015, 6, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, J.R.; Hindman, A.H. Scaffolding the persuasive writing of middle school students. Middle Grades Res. J. 2015, 10, 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Troia, G.A.; Graham, S. The consultant’s corner: Effective writing instruction across the grades: What every educational consultant should know. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 2003, 14, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Paz, S.; Graham, S. Explicitly teaching strategies, skills, and knowledge: Writing instruction in middle school classrooms. J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 94, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagaiah, T.; Howard, D.; Olinghouse, N. Writer’s checklist: A procedural support for struggling writers. Read. Teach. 2019, 73, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.A. Scaffolding literacy learning through talk: Stance as a pedagogical tool. Read. Teach. 2021, 74, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinert, J. Peer critique as a signature pedagogy in writing studies. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 2017, 16, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Edwards, J.G.H. Peer Response in Second Language Writing Classrooms; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Riazi, M.; Rezaii, M. Teacher- and peer-scaffolding behaviors: Effects on EFL students’ writing improvement. In Proceedings of the 12th National Conference for Community Languages and ESOL (CLESOL 2010), Auckland, New Zealand, 30 September–3 October 2010; TESOLANZ: Wellington, New Zealand, 2011; pp. 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pribadi, B.A.; Susilana, R. The use of mind mapping approach to facilitate students’ distance learning in writing modular based on printed learning materials. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 10, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabarun, S.; Muslimah, A.H.; Muhanif, S.; Elhawwa, T. The effect of flow mind map on writing accuracy and learning motivation at Islamic higher education. Lang. Circ. J. Lang. Lit. 2021, 16, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejayan, L.; Yunus, M.M. Application of digital mind mapping (MINDOMO) in improving weak students’ narrative writing performance. Creat. Educ. 2022, 13, 2730–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataineh, R.F.; Obeiah, S.F. The effect of scaffolding and portfolio assessment on Jordanian EFL learners’ writing. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 2016, 6, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhadon, L.; Wangmo, C. Improving essay writing skills through scaffolding instructions in grade six Bhutanese students. Rangsit J. Educ. Stud. 2022, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, G.E.; Gerde, H.K.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.Y. Supporting the writing development of emergent bilingual children: Universal and language-specific approaches. Read. Teach. 2023, 76, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, D.J. Scaffolding emergent writing in the zone of proximal development. Literacy 1998, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Stetson-Tiligadas, S.M. Building up to collaboration: Evidence on using wikis to scaffold academic writing. J. Acad. Writ. 2016, 6, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, M.; Saffari, E.; Rezaei, S. The impact of computer-aided concept mapping on EFL learners’ lexical diversity: A process writing experiment. ReCALL 2021, 33, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoori, M.; Kadivar, P.; Sarami, R. The effect of concept mapping strategy as a graphical tool in writing achievement among EFL learners. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2017, 7, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J. The efficacy of various kinds of error feedback for improvement in the accuracy and fluency of L2 student writing. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2003, 12, 267–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartshorn, K.J.; Evans, N.W.; Merrill, P.F.; Sudweeks, R.R.; Strong-Krause, D.; Anderson, N.J. Effects of dynamic corrective feedback on ESL writing accuracy. TESOL Q. 2010, 44, 84–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hier, B.O.; Eckert, T.L. Evaluating elementary-aged students’ abilities to generalize and maintain fluency gains of a performance feedback writing intervention. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2014, 29, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzan, T.; Buzan, B. The Mind Map Book; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Budd, J.W. Mind maps as classroom exercises. J. Econ. Educ. 2004, 35, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeds, A.J.; Kudrowitz, B.; Kwon, J. Mapping associations: Exploring divergent thinking through mind mapping. Int. J. Des. Creat. Innov. 2019, 7, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhindsa, H.S.; Anderson, R.O. Constructivist-visual mind map teaching approach and the quality of students’ cognitive structures. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2011, 20, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, M.-R. Kolb’s learning styles and educational outcome: Using digital mind map as a study tool in elementary English class. Int. J. Educ. Media Technol. 2012, 6, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Johnson, T.E.; Zhou, C. A pilot study examining the impact of collaborative mind mapping strategy in a flipped classroom: Learning achievement, self-efficacy, motivation, and students’ acceptance. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 3527–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, P.P. The use of mind mapping strategy in the teaching of writing at SMAN 3 Bengkulu, Indonesia. Int. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J. A research study on cognitive structure construction applying mind mapping in the construction of cognitive structures: A case study based on basic college English practice courses in universities. Zhongguo Dianhua Jiaoyu 2014, 329, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Khatib, M.; Meihami, H. Languaging and writing skill: The effect of collaborative writing on EFL students’ writing performance. Adv. Lang. Lit. Stud. 2015, 6, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, N. Collaborative writing: Product, process, and students’ reflections. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2005, 14, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. Making cooperative learning work. Theory Pract. 1999, 38, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housen, A.; Kuiken, F.; Vedder, I. Complexity, accuracy and fluency. In Dimensions of L2 Performance and Proficiency: Complexity, Accuracy and Fluency in SLA; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen-Freeman, D. The emergence of complexity, fluency, and accuracy in the oral and written production of five Chinese learners of English. Appl. Linguist. 2006, 27, 590–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skehan, P. A Cognitive Approach to Language Learning; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Laufer, B.; Nation, P. Vocabulary size and use: Lexical richness in L2 written production. Appl. Linguist. 1995, 16, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, J.A. Assessing Vocabulary; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Šišková, Z. Lexical richness in EFL students’ narratives. Lang. Stud. Work. Pap. 2012, 4, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe-Quintero, K.E.; Inagaki, S.; Kim, H.Y. Second Language Development in Writing: Measures of Fluency, Accuracy, & Complexity; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. National Language Standard: China’s Standards of English Language Ability. 2018. Available online: https://cse.neea.edu.cn/res/ceedu/1811/6bdc26c323d188948fca8048833f151a.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Hyerle, D. Thinking Maps: Tools for Learning; Innovative Learning Group: Troy, MI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R.; Barkhuizen, G. Analyzing Learner Language; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, A.H.; Berwick, R. (Eds.) Validation in Language Testing; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK, 1996; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, L. AntConc: Design and development of a freeware corpus analysis toolkit for the technical writing classroom. In Proceedings of the IPCC 2005 International Professional Communication Conference, Limerick, Ireland, 10–13 July 2005; pp. 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.W. A synopsis of clause-to-sentence length factors. Engl. J. 1965, 54, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnarud, M. Lexis in Composition: A Performance Analysis of Swedish Learners’ Written English; CWK Gleerup: Malmö, Sweden, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, S.; McNamara, D. Cohesion, coherence, and expert evaluations of writing proficiency. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society; Cognitive Science Society, Austin, TX, USA, 11–14 August 2010; Volume 32. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6n5908qx (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, H.J. Linguistic complexity in L2 writing revisited: Issues of topic, proficiency, and construct multidimensionality. System 2017, 66, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, B.S. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Cognitive Domain; Longmans: London, UK, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, H.C.; Lin, W.C.; Yang, S.C. Exploring the effects of peer review and teachers’ corrective feedback on EFL students’ online writing performance. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2015, 53, 284–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, B.; Kalantzis, M.; Abd-El-Khalick, F.; Bagley, E. Science in writing: Learning scientific argument in principle and practice. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2013, 10, 420–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzan, T. Mind Map Mastery: The Complete Guide to Learning and Using the Most Powerful Thinking Tool in the Universe; Watkins Media Limited: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, K.; Wong, L.L. (Eds.) Innovation and Change in English Language Education; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Lesson | Writing Topics | Writing Prompts |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Description of your best friend |

|

| 2 | Write a travel diary |

|

| 3 | Report of good/bad habits |

|

| 4 | Introduce your hometown |

|

| 5 | Write a movie review |

|

| 6 | Talk about future intentions |

|

| 7 | Write a recipe for your favorite food |

|

| 8 | Make/accept/decline an invitation |

|

| Sequence | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. | Enter the situation: The teacher introduced the topic of writing (e.g., describing one of their best friends) and got students ready for the following writing activities. |

| 2. | Set up scaffolding: Students brainstormed the topic, content, and structure using a mind mapping worksheet. |

| 3. | Independent exploration: Students worked on their mind mapping independently. |

| 4. | Cooperative learning: Students worked with their partners in pairs to enrich or expand their mind mapping through discussion, and then they started drafting. |

| 5. | Teacher review and evaluation: Students submitted their drafts for teacher review and revised their compositions when the teacher returned their writing compositions. |

| Pre-Test (n = 55) | Post-test (n = 55) | t | p Value | Cohen’s d | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | ||||

| Lexical complexity | 0.55 | 0.06 | 0.42−0.67 | 0.65 | 0.08 | 0.49−0.95 | 9.80 | <0.001 | 0.94 |

| Grammatical complexity | 5.81 | 0.79 | 3.89−7.14 | 6.50 | 0.96 | 4.10−8.50 | 5.23 | <0.001 | 0.54 |

| Accuracy | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.03−0.28 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.01−0.36 | 3.16 | <0.002 | 0.40 |

| Fluency | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.13−0.43 | 0.34 | 0.13 | 0.18−0.78 | 6.51 | <0.001 | 0.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, X.; Relyea, J.E. Exploring the Role of Mind Mapping Tools in Scaffolding Narrative Writing in English for Middle-School EFL Students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101119

Fu X, Relyea JE. Exploring the Role of Mind Mapping Tools in Scaffolding Narrative Writing in English for Middle-School EFL Students. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(10):1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101119

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Xinyan, and Jackie E. Relyea. 2024. "Exploring the Role of Mind Mapping Tools in Scaffolding Narrative Writing in English for Middle-School EFL Students" Education Sciences 14, no. 10: 1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101119

APA StyleFu, X., & Relyea, J. E. (2024). Exploring the Role of Mind Mapping Tools in Scaffolding Narrative Writing in English for Middle-School EFL Students. Education Sciences, 14(10), 1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101119