Inclusive Practices Outside of the United States: A Scoping Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What interventions are being used to support students with intellectual and developmental disabilities to access inclusive education outside of the United States?

- What are the characteristics of students and interventionists included in the extant research?

- Which outcomes and interventions have the highest success rates in these studies?

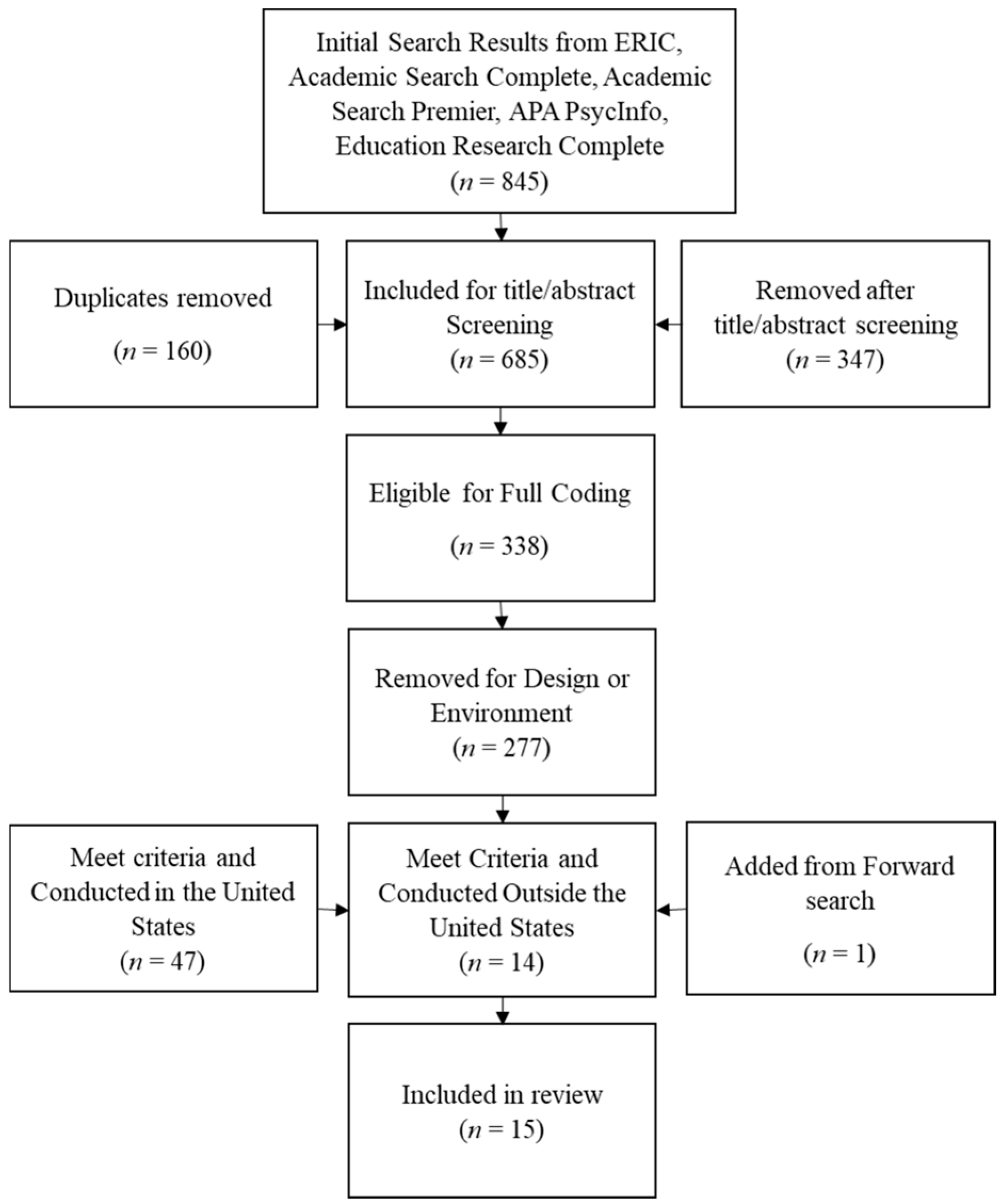

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategies

2.3. Coding Procedures

2.4. Coding Reliability

3. Results

3.1. Student Participants

3.2. Other Participants

3.3. Settings and Intervention Formats

3.4. Dependent Variables and Success Estimates

3.5. Independent Variables and Success Estimates

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Population | (“developmental disabilit *” OR “developmental del *” OR “intellectual disabilit *” OR “autis *” OR “autism spectrum disorder *” OR “mental * retard *” OR “down * syndrome” OR “handicap *” OR “multiple disabil * OR “ASD” OR “low-incidence disabil *” OR “significant disabil *” OR “severe disabil *” OR “complex communication need *” OR “complex communication challeng *” OR “cognitive impair *” OR “ABAS” OR “Wechsler Intel *” OR “ADOS” OR “ADI-R” OR “specal needs” OR “behavior disord *” OR “altern * assess *”) |

| Intervention | (“parapro *” OR “peer support” OR “peer network” OR “prompt *” OR “UDL” OR “universal design for learn *” OR “accomoda *” OR “modifica *” OR “embedded instruct *” OR “paraeduc *” OR “massed instruct *” OR “group contingenc” OR “classroom coach *” OR “collaboration” OR “explicit instruct *” OR “good behavior * game” OR “social skill *” OR “flex * group *” “strategy instruct *” OR “assistive tech *” OR “AAC” OR “augment * com *”) |

| Comparison | (“school” OR “class *” OR “preschool” OR “middle school” OR “high school” OR “junior high” OR “elementary school” OR “primary school” OR “secondary school” OR “separate class *” OR “special education class *” OR “Least Restrictive Environment” OR “LRE” OR “educational place *”) |

| Outcome | (“inclusi *” OR “mainstream *” OR “regular education class *” OR “general education class *” “push in” OR “co-teach *” OR “includ *”) |

| Study Methods | (“multiple-baseline” OR “multiple-probe” OR “reversal” OR “withdrawal” OR “single-subject” OR “single-case” OR “ABAB” OR “between-case *” OR “across-subject” OR “across-participant” OR “between-subject” OR “between-participant” OR “randomized control *” OR “between-group *” OR “across-behav *”) |

References

- UNESCO. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1994; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000098427 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- U.S. Government Printing Office. Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; Volume 301, p. 1400.

- Schalock, R.L.; Luckasson, R.; Tassé, M.J. An Overview of Intellectual Disability: Definition, Diagnosis, Classification, and Systems of Supports. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 126, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; text rev.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of European Union. Council Conclusions on the Social Dimension of Education and Training; Council of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2009; Available online: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/en/educ/114374.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Magnússon, G.; Göransson, K.; Lindqvist, G. Contextualizing inclusive education in educational policy: The case of Sweden. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2019, 5, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X. Making sense of policy development of inclusive education for children with disabilities in China. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 2024, 13, 2212585X241234332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.J.; Brock, M.E.; Shawbitz, K.N. Philosophical Perspectives and Practical Considerations for the Inclusion of Students with Developmental Disabilities. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehmeyer, M.L.; Shogren, K.A.; Kurth, J. The state of inclusion with students with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the United States. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 18, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, L.M.; Logan, J.A.; Lin, T.J.; Kaderavek, J.N. Peer effects in early childhood education: Testing the assumptions of special-education inclusion. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1722–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryndak, D.L.; Ward, T.; Alper, S.; Montgomery, J.W.; Storch, J.F. Long-term outcomes of services for two persons with significant disabilities with differing educational experiences: A qualitative consideration of the impact of educational experiences. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 2010, 45, 323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Travers, H.E.; Carter, E.W. A systematic review of how peer-mediated interventions impact students without disabilities. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2021, 43, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor, A.M.; Hagiwara, M.; Shogren, K.A.; Thompson, J.R.; Verdugo, M.Á.; Burke, K.M.; Aguayo, V. International perspectives and trends in research on inclusive education: A systematic review. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 2018, 23, 1277–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizunoya, S.; Mitra, S.; Yamasaki, I. Towards Inclusive Education: The Impact of Disability on School Attendance in Developing Countries—Innocenti Working Paper No. 2016-03; UNICEF Office of Research. 2016. Available online: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/IWP3%20-%20Towards%20Inclusive%20Education.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Plichta, P. Same progress for all? Inclusive education, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and students with intellectual disability in European countries. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 2021, 26, 1505–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurr, J.; Minuk, A.; Holmqvist, M.; Östlund, D.; Ghaith, N.; Reed, B. Parent perspectives on inclusive education for students with intellectual disability: A scoping review of the literature. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2023, 69, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacruz-Pérez, I.; Sanz-Cervera, P.; Tárraga-Mínguez, R. Teachers’ Attitudes toward Educational Inclusion in Spain: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeskey, J.; Maheady, L.; Billingsley, B.; Brownell, M.T.; Lewis, T.J. (Eds.) High Leverage Practices for Inclusive Classrooms; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dada, S.; Wilder, J.; May, A.; Klang, N.; Pillay, M. A review of interventions for children and youth with severe disabilities in inclusive education. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2278359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbrenner, J.R.; Hume, K.; Odom, S.L.; Morin, K.L.; Nowell, S.W.; Tomaszewski, B.; Savage, M.N. Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults with Autism; The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, National Clearinghouse on Autism Evidence and Practice Review Team: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kurth, J.A.; Ruppar, A.L.; McQueston, J.A.; McCabe, K.M.; Johnston, R.; Toews, S.G. Types of supplementary aids and services for students with significant support needs. J. Spec. Educ. 2019, 52, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M.E.; Huber, H.B. Are peer support arrangements an evidence-based practice? A systematic review. J. Spec. Educ. 2017, 51, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, J.; Johnson, J.W.; Polychronis, S.; Riesen, T.; Kercher, K.; Jameson, M. Comparison of one-to-one embedded instruction in general education classes with small group instruction in special education classes. Educ. Train. Dev. Disabil. 2006, 41, 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Gast, D.; Lloyd, B.; Ledford, J. Multiple baseline and multiple probe designs. In Single Case Research Methodology: Applications in Special and Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Ledford, J., Gast, D., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 239–282. [Google Scholar]

- Rakap, S.; Balikci, S.; Aydin, B.; Kalkan, S. Promoting inclusion through embedded instruction: Enhancing preschool teachers’ implementation of learning opportunities for children with disabilities. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2023, 35, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichow, B.; Volkmar, F.R. Social skills intervention for individuals with autism: Evaluation for evidence-based practices within a best evidence synthesis framework. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2010, 40, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British International Studies Association (BISA). Global South Countries. Available online: https://www.bisa.ac.uk/become-a-member/global-south-countries (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Fidan, A.; Tekin-Iftar, E. Effects of hybrid coaching on middle school teachers’ teaching skills and students’ academic outcomes in general education settings. Educ. Treat. Child. 2022, 45, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firat, O.A.; Ergenekon, Y. Effectiveness of the embedded instructions provided by preschool teachers on the acquisition of target behaviors by inclusion students. Egitim Bilim-Educ. Sci. 2021, 46, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyak, U.E.; Tekin-Iftar, E. General education teacher preparation in core academic content teaching for students with developmental disabilities. Behav. Interv. 2022, 37, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazak Pinar, E. Effectiveness of time-based attention schedules on students in inclusive classrooms in Turkey. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2015, 15, 1305–1316. [Google Scholar]

- Foreman, P.; Arthur-Kelly, M.; Bennett, D.; Neilands, J.; Colyvas, K. Observed changes in the alertness and communicative involvement of students with multiple and severe disabilities following in-class mentor modeling for staff in segregated and general education classrooms. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2014, 58, 704–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, L.J.; McClannahan, L.E.; Krantz, P.J. Promoting independence in integrated classrooms by teaching aides to use activity schedules and decreased prompts. Educ. Train. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. 1995, 30, 208–217. [Google Scholar]

- Imasaka, T.; Lee, P.L.; Anderson, A.; Wong, C.W.; Moore, D.W.; Furlonger, B.; Bussaca, M. Improving compliance in primary school students with autism spectrum disorder. J. Behav. Educ. 2020, 29, 763–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.E.; Mirenda, P. Contingency mapping: Use of a novel visual support strategy as an adjunct to functional equivalence training. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2006, 8, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guertin, E.L.; Vause, T.; Jaksic, H.; Frijters, J.C.; Feldman, M. Treating obsessive compulsive behavior and enhancing peer engagement in a preschooler with intellectual disability. Behav. Interv. 2019, 34, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, J.; Zhao, M.; Behrens, S.; Horn, E.M. Professional development improves teachers’ embedded instruction and children’s outcomes in a Chinese inclusive preschool. J. Behav. Educ. 2024, 33, 374–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J.H.; Tang, M.; Tsoi, S.P. Effects of a treatment package on the on-task behavior of a kindergartener with autism across settings. Behav. Dev. Bull. 2010, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- O’Reilly, M.; Tiernan, R.; Lancioni, G.; Lacey, C.; Hillery, J.; Gardiner, M. Use of self-monitoring and delayed feedback to increase on-task behavior in a post-institutionalized child within regular classroom settings. Educ. Treat. Child. 2002, 25, 91–102. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42900517 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Aldabas, R. Effects of peer network intervention through peer-led play on basic social communication skills of children with autism spectrum disorder in inclusive classrooms. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2022, 34, 1121–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho Blair, K.-S.; Umbreit, J.; Dunlap, G.; Jung, G. Promoting inclusion and peer participation through assessment-based intervention. Topics Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2007, 27, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Students with Disabilities | ||

|---|---|---|

| Work Completion | Social and Communication | Engagement & Challenging Bx |

| Number correct 4/4 [25] Percent correct 1/4 [28] Percent correct 4/4 [29] Percent correct 3/3 [30] Work completion * (n/a) [36] Percent correct 1/3 [37] Number correct 3/3 [40] | Interactions 0/8 [32] Engagement with peer * (n/a) [36] Interactions 3/3 [40] Initiations 3/3 [40] | Awake/Alert 1/8 [32] On task 1/3 [33] On schedule 0/3 [33] Compliance * 2/3 [34] On task * 2/3 [34] Latency between tasks 0/3 [35] Challenging Bx 1/3 [35] Morning routine * (n/a) [36] On task 1/3 [38] Replacement Bx 0/3 [41] Appropriate Bx 0/3 [41] |

| Success Estimate: 16/21 = 76.2% | Success Estimate: 6/14 = 42.9% | Success Estimate: 11/46 = 23.9% |

| Classroom Staff | Peers without Disabilities | |

| Intervention Implementation | Use of Systematic Prompts | Peer Behavior |

| Number correct 4/4 [25] Percent correct 4/4 [28] Self-monitor 3/3 [30] Percent correct 3/3 [37] Positive interactions 3/3 [41] | Simultaneous prompts 3/3 [30] Physical prompt 0/3 [33] Verbal prompt 1/3 [33] Gestural prompt 1/3 [33] | On task * 0/3 [34] Positive interactions 3/3 [41] |

| Success Estimate: 17/17 = 100% | Success Estimate: 5/12 = 41.7% | Success Estimate: 3/6 = 50% |

| Rf/Praise | Prompting/ Modeling | Alternative Bx | Embedded Instruction | Peer Mediated | Visual/ Antecedent | Conting. Mapping | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ai and colleauges [37] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Aldabas [40] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Brown and Mirenda [35] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Cho Blair and colleauges [41] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Fidan and Tekin-Iftar [28] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Firat and Ergenekon [29] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Foreman and colleauges [32] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Greenberg and colleagues [38] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Guertin and colleagues [36] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Hall and colleagues [33] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Imasaka and colleauges [34] | ✓ | ||||||

| Kiyak and Tekin-Iftar [30] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| O’Reilly and colleagues [39] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Rakap and colleauges [25] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Sazak Pinar [31] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Strategy | Rf/Praise | Prompting/Modeling | Alternative Bx | Embedded Instruction | Peer Mediated | Visual/Antecedent | Conting. Mapping |

| Number of studies with strategy | 15 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Success Estimate for Student DV | 33/81 = 40.7% | 10/20 = 50% | 4/20 = 20% | 9/11 = 81.8% | 10/25 = 40% | 1/6 = 16.7% | 1/6 = 16.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anderson, E.J.; Oehrtman, E.; Cohara, E.K. Inclusive Practices Outside of the United States: A Scoping Literature Review. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1140. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14111140

Anderson EJ, Oehrtman E, Cohara EK. Inclusive Practices Outside of the United States: A Scoping Literature Review. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(11):1140. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14111140

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnderson, Eric J., Emily Oehrtman, and Elizabeth K. Cohara. 2024. "Inclusive Practices Outside of the United States: A Scoping Literature Review" Education Sciences 14, no. 11: 1140. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14111140

APA StyleAnderson, E. J., Oehrtman, E., & Cohara, E. K. (2024). Inclusive Practices Outside of the United States: A Scoping Literature Review. Education Sciences, 14(11), 1140. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14111140