Research Impact and Sustainability in Education: A Conceptual Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

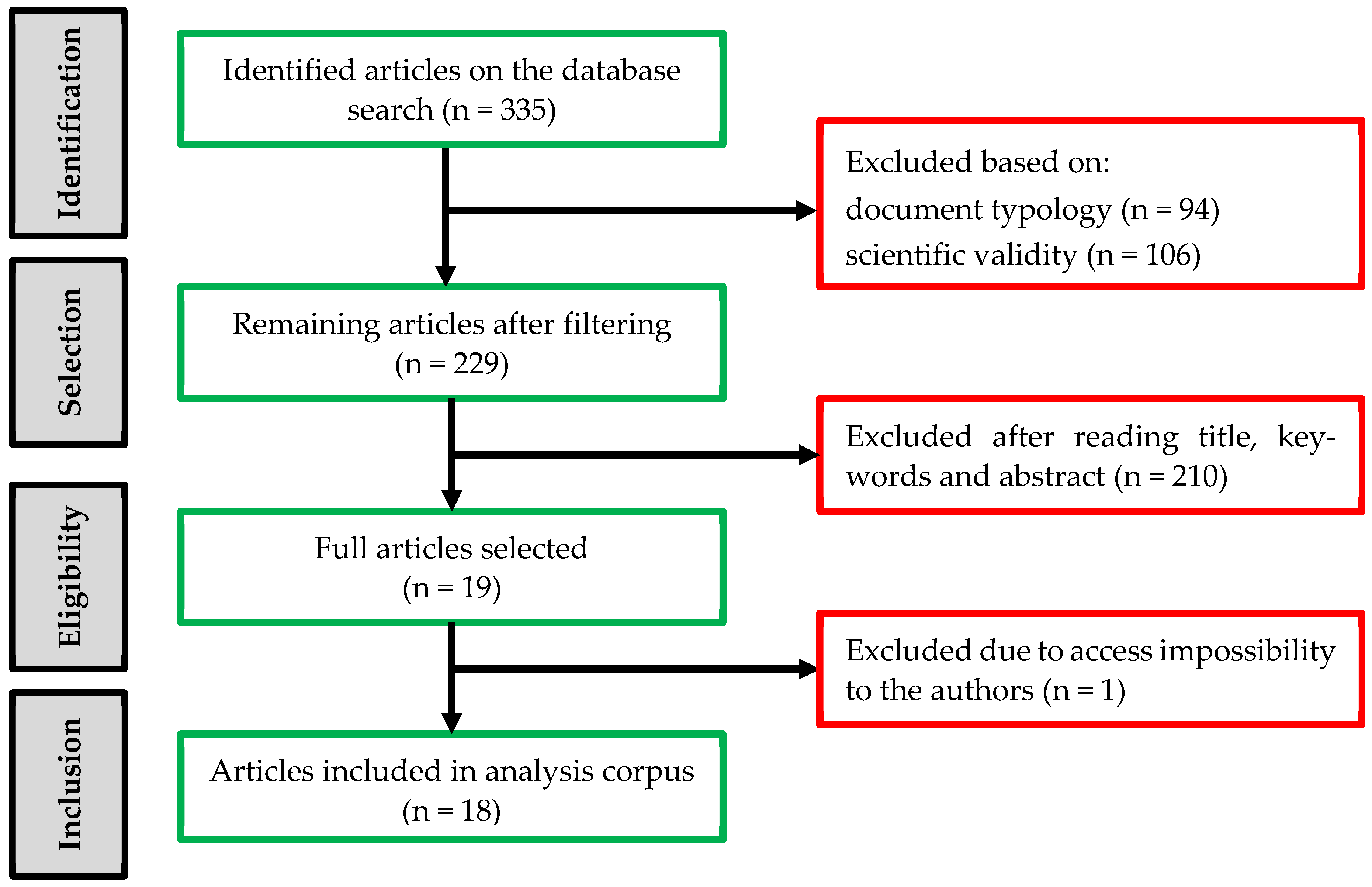

2.1. Corpus Selection Process

2.2. Data Analysis Procedures

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Research Sustainability

3.2. Research Impact

3.3. The (Inter)relation between Research Sustainability and Research Impact

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Research Impact—Corpus

| Code | Reference | Language | Keywords |

| A1 | Yates, L. Is Impact a Measure of Quality? Some Reflections on the Research Quality and Impact Assessment Agendas. European Educational Research Journal 2005, 4, 391–403. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2005.4.4.5 | English | None |

| A2 | Scoble, R.; Dickson, K.; Hanney, S.; Rodgers, G.J. Institutional Strategies for Capturing Socio-Economic Impact of Academic Research. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 2010, 32, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2010.511122 | English | Research assessment, research capital, research strategy, socio-economic impact |

| A3 | Upton, S. Identifying Effective Drivers for Knowledge Exchange in the United Kingdom. Higher Education Management and Policy 2012, 24, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1787/hemp-24-5k9bdsv6wms1 | English | None |

| A4 | Knight, C.; Lightowler, C. Sustaining knowledge exchange and research impact in the social sciences and humanities: Investing in knowledge broker roles in UK universities. Evidence and Policy 2013, 9. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426413X662644 | English | Higher education, knowledge brokers, knowledge exchange, research impact |

| A5 | Oancea, A. Research Impact and Educational Research. European Educational Research Journal 2013, 12, 242–250. http://dx.doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2013.12.2.242 | English | None |

| A6 | Smith, K.; Crookes, E.; Crookes, P. Measuring research ‘impact’ for academic promotion: issues from the literature, Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 2013, 35, 410–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2013.812173 | English | Bibliometrics, ERA, Excellence in Research for Australia, impact, research quality |

| A7 | Naidorf, J. Knowledge Utility: From Social Relevance to Knowledge Mobilization. Education Policy Analysis Archives 2014, 22, 1–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v22n89.2014 | English | Knowledge utility, social relevance of research, knowledge mobilization, scientific policy |

| A8 | Hazelkorn, E. Making an impact: New directions for arts and humanities research. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 2015, 14, 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022214533891 | English | Arts and humanities, economic development, global crisis, impact, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway |

| A9 | Gunn, A.; Mintrom, M. Evaluating the non-academic impact of academic research: design considerations. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 2017, 39, 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2016.1254429 | English | Academic research, evaluation methods, policy design, research assessment, research funding cycles, research impact, non- academic impact |

| A10 | Doyle, J. Reconceptualising research impact: reflections on the real-world impact of research in an Australian context. Higher Education Research & Development 2018, 37, 1366–1379. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1504005 | English | Higher education policy, research impact, Australia, academic identity, qualitative research |

| A11 | Mitchell, V. A proposed framework and tool for non-economic research impact measurement. Higher Education Research & Development 2019, 38, 819–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1590319 | English | Impact policy, impact measurement, research outcomes, research evaluation |

| A12 | O’Connell, C. Examining differentiation in academic responses to research impact policy: mediating factors in the context of educational research. Studies in Higher Education 2019, 44, 1438–1453. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1447556 | English | Policy analysis, relational perspective, research policy, tertiary education, institutional research |

| A13 | Scruggs, R.; McDermott, P.; Qiao, X. A Nationwide Study of Research Publication Impact of Faculty in U.S. Higher Education Doctoral Programs. Innovative Higher Education 2019, 44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-018-9447-x | English | Higher education, doctoral education, h-index, research impact |

| A14 | Wilkinson, C. Evidencing impact: a case study of UK academic perspectives on evidencing research impact. Studies in Higher Education 2019, 44, 72–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1339028 | English | Impact, research, engagement, evidence, assessment |

| A15 | Gunn, A.; Mintrom, M. Measuring research impact in Australia. Australian Universities’ Review 2020, 60, 9–15 | English | Higher education, research funding, research evaluation, impact and engagement, innovation policy |

| A16 | Jerome, L. Making sense of the impact agenda in UK higher education: A case study of Preventing Violent Extremism policy in schools. Journal of Social Science Education 2020, 19, 8–23. https://doi.org/10.4119/jsse-1558 | English | Impact, evaluation, performativity, preventing violent extremism (PVE), Prevent |

| A17 | Papatsiba, V.; Cohen, E. Institutional hierarchies and research impact: new academic currencies, capital and position-taking in UK higher education. British Journal of Sociology of Education 2020, 41, 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2019.1676700 | English | Research Excellence Framework, research policy, impact, universities, Bourdieu |

| A18 | Woolcott, G.; Keast, R.; Pickernell, D. Deep impact: re-conceptualising university research impact using human cultural accumulation theory. Studies in Higher Education 2020, 45, 1197–1216. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1594179 | English | Impact, collaboration, university research, social network analysis, university- community |

Appendix B. Research Sustainability—Corpus

| Code | Reference | Language | Keywords |

| A19 | Sharp, A. ELT project planning and sustainability. ELT Journal 1998, 52, 140–145. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/52.2.140 | English | None |

| A20 | Loh, L., Friedman, S. & Burdick, W. Factors Promoting Sustainability of Education Innovations: A Comparison of Faculty Perceptions and Existing Frameworks. Education for Health 2013, 26, 32–38. https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.112798 | English | Developing countries, medical education, medical faculty, organizational innovation, program sustainability |

| A21 | Abou-Warda, S. Mediation effect of sustainability competencies on the relation between barriers and project sustainability (the case of Egyptian higher education enhancement projects). Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 2014, 5, 68–94. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-04-2011-0017 | English | None |

| A22 | Guerra, C.; Costa, N. Sustentabilidade da investigação educacional: contributos da literatura sobre o conceito, fatores e ações. Revista Lusófona da Educação 2016, 13–25 | Portuguese | Project manager, sustainability management, sustainability competencies, barriers to sustainability, Egyptian HEEPs, project sustainability |

| A23 | Sánchez, L.; Mitchell, R. Conceptualizing impact assessment as a learning process. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2016, 62, 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2016.06.001 | English | Sustentabilidade da investigação, investigação educacional, avaliação do impacte da investigação |

| A24 | Sánchez-Carracedo, F.; Cabré, J.; Alier, M.; Vidal, E.; López, D.; Martín, C.; García, J. A Learning Tool to Develop Sustainable Projects. IEE Frontiers in Education Conference 2016, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE.2016.7757468 | English | Sustainability, engineering projects, final degree projects |

| A25 | Sparks, J.; Rutkowski, D. Exploring project sustainability: using a multiperspectival, multidimensional approach to frame inquiry. Development in Practice 2016, 26, 308–320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2016.1153041 | English | Aid-Aid effectiveness, monitoring and evaluation, development policies, civil society-partnership, participation, social sector-education |

| A26 | Aarseth, W.; Ahola, T.; Aaltonen, K.; Okland, A.; Andersen, B. Project sustainability strategies: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Project Management 2017, 35, 1071–1083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.11.006 | English | Sustainability, project management, project host, sustainability strategies |

| A27 | Aga, D.; Noorderhaven, N.; Vallejo, B. Project beneficiary participation and behavioural intentions promoting project sustainability: The mediating role of psychological ownership. Development Policy Review 2017, 36, 527–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12241 | English | Community participation, project sustainability, psychological ownership |

| A28 | Guerra, C.; Costa, N. Educational innovations in Engineering education: sustainability of funded projects developed in Portuguese higher education institutions. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of the Portuguese Society for Engineering Education, Aveiro, Portugal, 27–29 June 2018. https://doi.org/10.1109/CISPEE.2018.8593497 | English | Educational innovations, engineering education; sustainability of funded research; Portuguese higher education institutions |

| A29 | Khalifeh, A.; Farrell, P.; Al-edenat, M. The impact of project sustainability management (PSM) on project success: a systematic literature review. Journal of Management Development 2019, 39, 453–474. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-02-2019-0045 | English | Project management, sustainability, project, project success, project sustainability management, triple-bottom line |

| A30 | Guerra, C. Sustentabilidade da investigação em educação: da concepção à implementação de um referencial. Revista Práxis Educacional 2021, 17, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.22481/praxisedu.v17i48.8819 | Portuguese | Sustentabilidade da investigação; inovações educativas; investigação & desenvolvimento |

| A31 | Guerra, C.; Costa, N. Can Pedagogical Innovations Be Sustainable? One Evaluation Outlook for Research Developed in Portuguese Higher Education. Education Sciences 2021, 11, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110725 | English | Sustainability of research, institutional support, political and research agendas, projects dynamics |

References

- Guerra, C. Sustentabilidade da investigação em educação: Da concepção à implementação de um referencial. Rev. Práxis Educ. 2021, 17, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, T.; Nowotny, H.; Schuch, K. Impact re-loaded. Fteval J. Res. Technol. Policy Eval. 2019, 48, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarseth, W.; Ahola, T.; Aaltonen, K.; Okland, A.; Andersen, B. Project sustainability strategies: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oancea, A. Research Impact and Educational Research. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 12, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Research Council Work Programme 2022; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/docs/2021-2027/horizon/wp-call/2022/wp_horizon-erc-2022_en.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- Aga, D.; Noorderhaven, N.; Vallejo, B. Project beneficiary participation and behavioural intentions promoting project sustainability: The mediating role of psychological ownership. Dev. Policy Rev. 2017, 36, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoble, R.; Dickson, K.; Hanney, S.; Rodgers, G.J. Institutional Strategies for Capturing Socio-Economic Impact of Academic Research. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2010, 32, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanholsbeeck, M.; Lendák-Kabók, K. Research impact as a ‘boundary object’ in the social sciences and the humanities. Word Text 2020, 10, 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen, L.; Phelps, S.F.; Kimmons, R. Introduction to literature reviews. In Rapid Academic Writing, 2nd ed.; Kimmons, R., West, R.E., Eds.; EdTech Books: Utah, UT, USA, 2018; Available online: https://edtechbooks.org/rapidwriting/lit_rev_intro (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Amundsen, C.; Wilson, M. Are We Asking the Right Questions?: A Conceptual Review of the Educational Development Literature in Higher Education. Rev. Educ. Res. 2012, 82, 90–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 89–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, T.; Alarcão, I.; Celorico, J.A. Revisão da Literatura e Sistematização do Conhecimento; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, M.; Gough, D. Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application. In Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application, 1st ed.; Zawacki-Richter, O., Kerres, M., Bedenlier, S., Bond, M., Buntins, K., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, R.C.; Biklen, S.K. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theories and Methods, 5th ed.; Pearson A & B: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, C.P. Metodologia de Investigação em Ciências Sociais e Humanas: Teoria e Prática, 2nd ed.; Almedina: Coimbra, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo, 4th ed.; Edições 70; Lda: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, J.Z. The Tyranny of Metrics, 1st ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, W. Informal Sociology: A Casual Introduction to Sociological Thinking, 6th ed.; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- REF. Research Excellence Framework 2014: The Results; Research Excellence Framework: Bristol, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/research/environment/assessment/ref2014/ (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- Mercer-Mapstone, L.; Kuchel, L. Core Skills for Effective Science Communication: A Teaching Resource for Undergraduate Science Education. Int. J. Sci. Educ. Part B 2015, 7, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidorf, J. Knowledge Utility: From Social Relevance to Knowledge Mobilization. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2014, 22, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Crookes, E.; Crookes, P. Measuring research ‘impact’ for academic promotion: Issues from the literature. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2013, 35, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Descriptors |

|---|---|

| The document is a scientific article. |

| The article is in open access. |

| The article was submitted to peer review. |

| The article is written in one of the following languages, according to the authors’ linguistic competences: Portuguese, English or Spanish. |

| The article meets the research question and objectives for the proposed literature review. |

| Database | Search Code | Results | Included |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERIC | “project sustainability” 1 | 73 | 1 |

| Scielo | sustentabilidade da investigação 2 | 85 | 0 |

| Redalyc | “sostenibilidad de la investigación” | 77 | 1 |

| Google Scholar | “sustentabilidade da investigação” | 48 | 4 |

| Scopus | “project sustainability” AND education | 77 | 7 |

| ISI | “project sustainability” AND education | 177 | 4 |

| Emerald | “project sustainability” AND education | 195 | 2 |

| Science Direct | “project sustainability” 3 | 128 | 2 |

| Sustainability | Common Zone | Impact | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-project | Research design | Pre-project | ||

| During the project | Institutional and organizational support | Science communication | During the project | |

| Sustainability competences | Community engagement | Lack of training | ||

| Program champions | Funding | Knowledge brokerage | ||

| Feeling of belonging | Monitorization and assessment | Research methodology | ||

| Overlapping positions and lack of time | ||||

| Post-project | Peer support | Results | Post-project |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres, R.; Simões, A.R.; Pinto, S. Research Impact and Sustainability in Education: A Conceptual Literature Review. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020147

Torres R, Simões AR, Pinto S. Research Impact and Sustainability in Education: A Conceptual Literature Review. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(2):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020147

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres, Ricardo, Ana Raquel Simões, and Susana Pinto. 2024. "Research Impact and Sustainability in Education: A Conceptual Literature Review" Education Sciences 14, no. 2: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020147

APA StyleTorres, R., Simões, A. R., & Pinto, S. (2024). Research Impact and Sustainability in Education: A Conceptual Literature Review. Education Sciences, 14(2), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020147