Outcomes of Equity-Based Multi-Tiered System of Support and Instructional Decision-Making for Autistic Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. A Schoolwide Approach to Providing Instruction and Support to Autistic Students: Challenges and Considerations

1.2. Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) for Students with Disabilities

1.3. Equity-Based MTSS

1.4. Intensified Support in Equity-Based MTSS

- To what extent do autistic students show an improvement in their scores on English Language, Arts, and Mathematics summative assessments (e.g., SBAC) after the implementation of an equity-based MTSS?

- To what extent do autistic students move to a less-restrictive educational environment in a school following the implementation of an equity-based MTSS?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Academic Outcomes

2.3.2. Least Restrictive Educational Environment

2.3.3. Fidelity of Implementation

2.4. Research Design and Analysis

3. Results

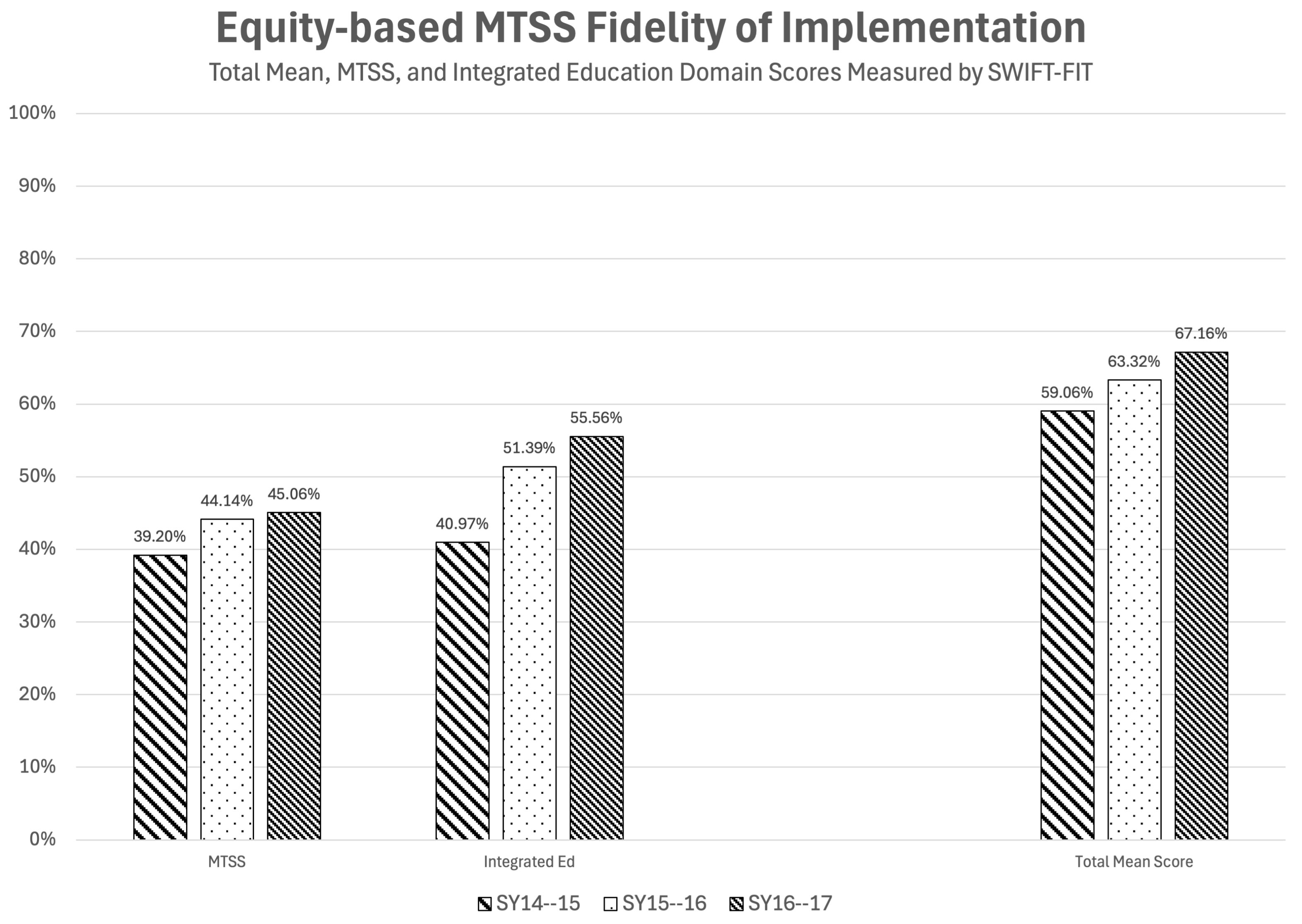

3.1. Fidelity of Equity-Based MTSS Implementation

3.2. Academic Outcome Improvement

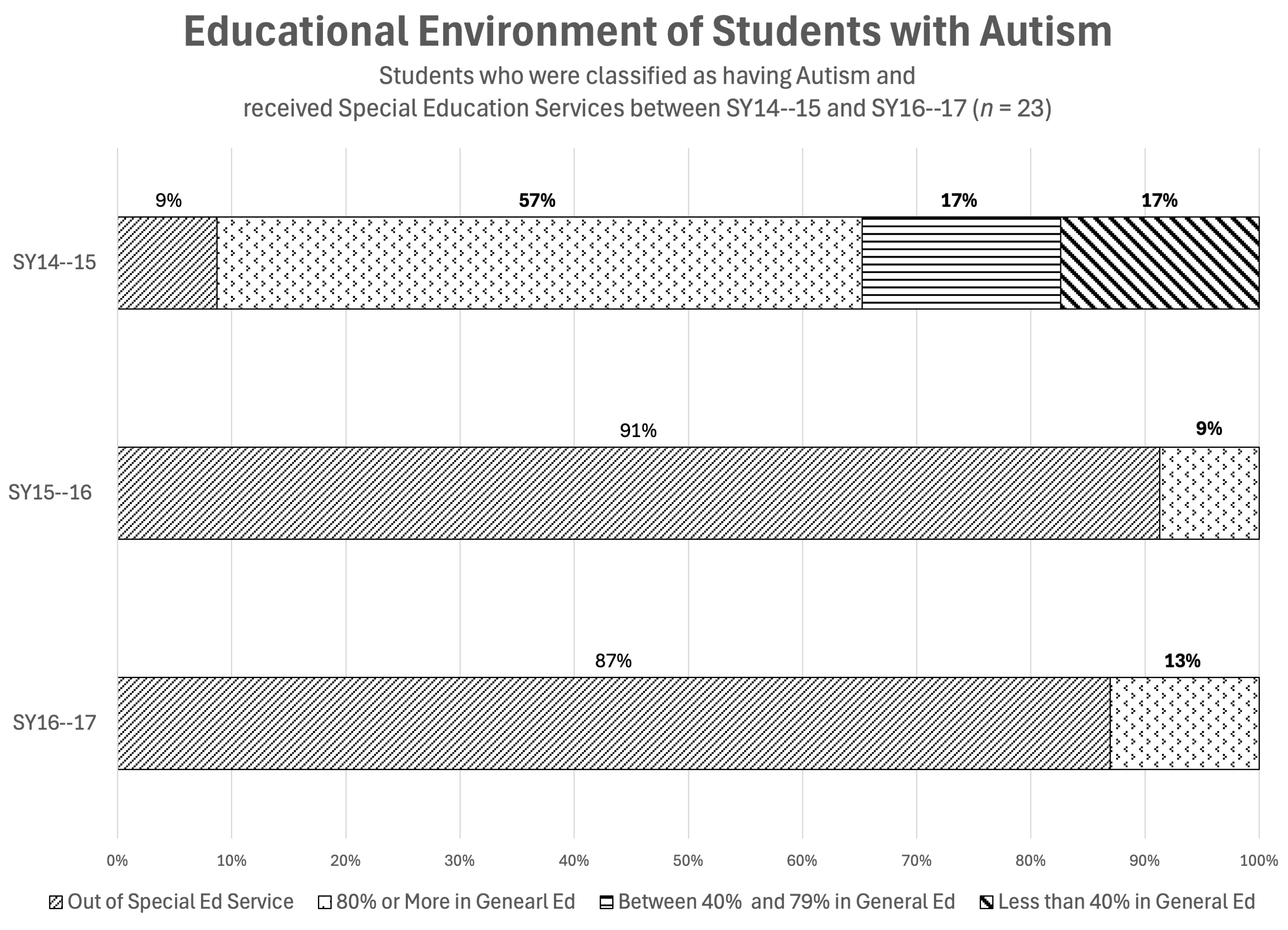

3.3. Least Restrictive Educational Environment

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Joseph, R.; Tager-Flusberg, H.; Lord, C. Cognitive profiles and social-communicative functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2002, 43, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casten, L.; Thomas, T.; Doobay, A.; Foley-Nicpon, M.; Kramer, S.; Nickl-Jockschat, T.; Abel, T.; Assouline, S.; Michaelson, J. The combination of autism and exceptional cognitive ability is associated with suicidal ideation. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2023, 197, 107698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keen, D.; Webster, A.; Ridley, G. How well are children with autism spectrum disorder doing academically at school? An overview of the literature. Autism 2015, 20, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashburner, J.; Ziviani, J.; Rodger, S. Surviving in the mainstream: Capacity of children with autism spectrum disorders to perform academically and regulate their emotions and behavior at school. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2010, 4, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, G.; Tseng, W.; Chiu, Y.; Tsai, W.; Wu, Y.; Gau, S. Executive functions in youths with autism spectrum disorder and their unaffected siblings. Psychol. Med. 2020, 51, 2571–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappadocia, M.; Weiss, J.; Pepler, D. Bullying experiences among children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2011, 42, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, G.; Drastal, K.; Hartley, S. Cross-lagged model of bullying victimization and mental health problems in children with autism in middle to older childhood. Autism 2020, 25, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, M.; Adamson, C.; Griffiths, D. What helps young people at risk of exclusion to remain in high school? Using Q methodology to hear student voices. Pastor. Care Educ. 2024, 42, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krezmien, M.; Travers, J.; Camacho, K. Suspension rates of students with autism or intellectual disabilities in Maryland from 2004 to 2015. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2017, 61, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitsika, V.; Sharpley, C.; Heyne, D. Risk for school refusal among autistic boys bullied at school:Investigating associations with social phobia and separation anxiety. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2021, 69, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totsika, V.; Hastings, R.; Dutton, Y.; Worsley, A.; Melvin, G.; Gray, K.; Tonge, B.; Heyne, D. Types and correlates of school non-attendance in students with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2020, 24, 1639–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersson-Bloom, L.; Leifler, E.; Holmqvist, M. The use of professional development to enhance education of students with autism: A systematic review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Simpson, K. A review of research into stakeholder perspectives on inclusion of students with autism in mainstream schools. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2016, 20, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailor, W.; McCart, A.; Choi, J. Reconceptualizing inclusive education through multi-tiered system of support. Inclusion 2018, 6, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailor, W.S.; McCart, A.B. Stars in alignment. Res. Prac. Persons Severe Disabil. 2014, 39, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusumano, D.; Preston, A. Supporting inclusive practices with multi-tiered system of supports. In Handbook of Effective Inclusive Elementary Schools; McLeskey, J., Spooner, F., Algozzine, B., Waldron, N.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 117–138. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Promising Practices: Inclusion, Equity, Opportunity. Available online: https://www2.ed.gov/about/inits/ed/earlyliteracy/k-3-literacy-multi-tiered-systems-of-support.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Sailor, W.; Skrtic, T.; Cohn, M.; Olmstead, C. Preparing teacher educators for statewide scale-up of multi-tiered system of support (MTSS). Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. J. Teach. Educ. Div. Counc. Except. Child. 2018, 44, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, K.; Goodman, S. Integrated Multi-Tiered Systems of Support, 1st ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thurlow, M.; Ghere, G.; Lazarus, S.; Liu, K. MTSS for All: Including Students with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities; University of Minnesota, TIES Center and National Center on Educational Outcomes: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020; Available online: https://tiescenter.org/resource/yD/BRnb7fSLmKEa700Hv46Q (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Agran, M.; Jackson, L.; Kurth, J.; Ryndak, D.; Burnette, K.; Jameson, M.; Zagona, A.; Fitzpatrick, H.; Wehmeyer, M. Why aren’t students with severe disabilities being placed in general education classrooms: Examining the relations among classroom placement, learner outcomes, and other factors. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2019, 45, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, W.; Stormont, M.; Herman, K.; Wang, Z.; Newcomer, L.; King, K. Use of Coaching and Behavior Support Planning for Students With Disruptive Behavior Within a Universal Classroom Management Program. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2014, 22, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, M. Implementing evidence-based practices within multi-tiered systems of support to promote inclusive secondary classroom settings. J. Spec. Educ. Apprenticesh. 2020, 9, n1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, S.; Meadan, H. Social inclusion of children with persistent challenging behaviors. Early Child. Educ. J. 2020, 50, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; McCart, A.; Sailor, W. Achievement of students with IEPs and associated relationships with an inclusive MTSS framework. J. Spec. Educ. 2020, 54, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCart, A.; Sailor, W.; Bezdek, J.; Satter, A. A framework for inclusive educational delivery systems. Inclusion 2014, 2, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; McCart, A.; Sailor, W. Reshaping educational systems to realize the promise of inclusive education. FIRE Forum Int. Res. Educ. 2020, 6, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaabi, A.M.; Abdallah, A.K.; Badwy, H.R.; Badawy, H.R.; Almammari, S.A. Rethinking school principals’ leadership practices for an effective and inclusive education. In Rethinking Inclusion and Transformation in Special Education; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bays, D.; Crockett, J. Investigating instructional leadership for special education. Exceptionality 2007, 15, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, J.; Lenkeit, J.; Hartmann, A.; Ehlert, A.; Knigge, M.; Spörer, N. The effect of school leadership on implementing inclusive education: How transformational and instructional leadership practices affect individualised education planning. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 26, 943–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrich, L.C.; Carrington, S. Making sense of ethical leadership. In Promoting Equity in Schools: Collaboration, Inquiry and Ethical Leadership; Harris, J., Carrington, S., Ainscow, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Berges Puyo, J. Ethical leadership in education: A uniting view through ethics of care, justice, critique, and heartful education. J. Cult. Values Educ. 2022, 5, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBrayer, K.; Deng, M. Plotting an emerging relationship schema of effective leadership attributes for inclusive schools. Int. J. Learn. Change 2017, 9, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Óskarsdóttir, E.; Donnelly, V.; Turner-Cmuchal, M.; Florian, L. Inclusive school leaders—Their role in raising the achievement of all learners. J. Educ. Adm. 2020, 58, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traver-Martí, J.; Ballesteros-Velázquez, B.; Beldarrain, N.; Maiquez, M. Leading the curriculum towards social change: Distributed leadership and the inclusive school. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2021, 51, 554–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, W.; Struyven, K. A teachers’ professional development programme to implement differentiated instruction in secondary education: How far do teachers reach? Cogent Educ. 2020, 7, 1742273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, I.; Lesesne, C.; Sun, J.; Johns, M.; Zhang, X.; Hertz, M. The relationship of school connectedness to adolescents’ engagement in co-occurring health risks: A meta-analytic review. J. Sch. Nurs. 2024, 40, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablotsky, B.; Boswell, K.; Smith, C. An evaluation of school involvement and satisfaction of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 117, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, E.; Shochet, I.; Cockshaw, W.; Kelly, R. General belonging is a key predictor of adolescent depressive symptoms and partially mediates school belonging. Sch. Ment. Health 2020, 12, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, A.; Cole-Lewis, Y.; Lindsay, R.; Yeguez, C.; Clark, M.; King, C. The protective role of connectedness on depression and suicidal ideation among bully victimized youth. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2018, 48, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, J.; McChesney, K. The relationships between school climate and adolescent mental health and wellbeing: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 88, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwar, R.; Adhikari, S. An exploration of the conceptualization, guiding principles, and theoretical perspectives of inclusive curriculum. J. Contemp. Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, S.; Saggers, B.; Shochet, I.; Orr, J.; Wurfl, A.; Vanelli, J.; Nickerson, J. Researching a whole school approach to school connectedness. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 27, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, A. The role of social and emotional learning during the transition to secondary school: An exploratory study. Pastor. Care Educ. 2019, 38, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Carney, J.; Hazler, R. Promoting school connectedness: A critical review of definitions and theoretical models for school-based interventions. Prev. Sch. Fail. Altern. Educ. Child. Youth 2022, 67, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, J.; Moore-Thomas, C.; Gaenzle, S.; Kim, J.; Lin, C.; Na, G. The effects of school bonding on high school seniors’ academic achievement. J. Couns. Dev. 2012, 90, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.; Gillett-Swan, J.; Killingly, C.; Van Bergen, P. Does it matter if students (dis)like school? Associations between school liking, teacher and school connectedness, and exclusionary discipline. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 825036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, M.; Talbert, J. Reforming Districts: How Districts Support School Reform; Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy: Seattle, WA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kozleski, E.; Smith, A. The complexities of systems change in creating equity for students with disabilities in urban schools. Urban Educ. 2020, 44, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leytham, P.; Nguyen, N.; Rago, D. Curriculum programming in the general education setting for students with autism spectrum disorder. Teach. Except. Child. 2020, 53, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, A. Evidence-based practices for teaching learners on the autism spectrum. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.; Walker, V.; Shogren, K.; Wehmeyer, M. Expanding inclusive educational opportunities for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities through personalized supports. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 56, 396–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCart, A.; Miller, D. Leading Equity-Based MTSS for All Students; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McCart, A.; McSheehan, M.; Sailor, W.; Mitchiner, M.; Quirk, C. SWIFT Differentiated Technical Assistance (White Paper). (SWIFT Center, 2016). Available online: https://swiftschools.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/10-SWIFT-Differentiated-Technical-Assistance.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium: 2014–15 Technical Report. Available online: https://portal.smarterbalanced.org/library/en/2014-15-technical-report.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Algozzine, B.; Sweeney, H.; Choi, J.; Horner, R.; Sailor, W.; McCart, A.; Satter, A.; Lane, K. Development and preliminary technical adequacy of the schoolwide integrated framework for transformation fidelity of implementation tool. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2016, 35, 302–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center on Intensive Intervention. In Planning Standards-Aligned Instruction within a Multi-Tiered System of Support; American Institutes for Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Kamps, D.; Leonard, B.; Potucek, J.; Garrison-Harrell, L. Cooperative learning groups in reading: An integration strategy for students with autism and general classroom peers. Behav. Disord. 1995, 21, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, A.; Sawyer, M.; Alber-Morgan, S.; Boggs, M. Effects of a graphic organizer training package on the persuasive writing of middle school students with autism. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 2015, 50, 290–302. [Google Scholar]

- Carnahan, C.; Williamson, P. Does compare-contrast text structure help students with autism spectrum disorder comprehend science text? Except. Child. 2013, 79, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marble-Flint, K.; Brown, B. Self-regulated strategy development for writing: Case study of a female with autism spectrum disorder. Commun. Disord. Q. 2022, 44, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, H.; Remington, A.; Hill, V. Developing an intervention to improve reading comprehension for children and young people with autism spectrum disorders. Educ. Child Psychol. 2017, 34, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, T.; Hughes, M. Exploring computer and storybook interventions for children with high functioning autism. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2012, 27, 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.; Hawley, K.; Browder, D.; Flowers, C.; Wakeman, S. Teaching writing in response to text to students with developmental disabilities who participate in alternate assessments. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 2016, 51, 238–251. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz, J.; Flores, M. The effectiveness of direct instruction for teaching language to children with autism spectrum disorders: Identifying materials. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 39, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlosser, R.; Blischak, D. Effects of speech and print feedback on spelling by children with autism. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2004, 47, 848–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakeman, S.; Karvonen, M.; Flowers, C.; Ruhter, L. Alternate assessment and monitoring student progress in inclusive classrooms. In Handbook of Effectiveinclusive Elementary Schools: Research And Practice; McLeskey, J., Spooner, F., Algozzine, B., Waldron, N.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhter, L.; Karvonen, M. The impact of professional development on data-based decision-making for students with extensive support needs. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2023, 45, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education. IDEA Section 618 Data Products: Static Tables. Available online: https://www2.ed.gov/programs/osepidea/618-data/static-tables/index.html (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- Boujut, E.; Popa-Roch, M.; Palomares, E.; Dean, A.; Cappe, E. Self-efficacy and burnout in teachers of students with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2017, 36, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, N. Investigating Whether Implementation of MTSS and UDL Frameworks Correlate to Teachers’ Attitudes, Knowledge, and Confidence in Teaching Students with Autism in Mainstream Classrooms; California Council on Teacher Education SPAN: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

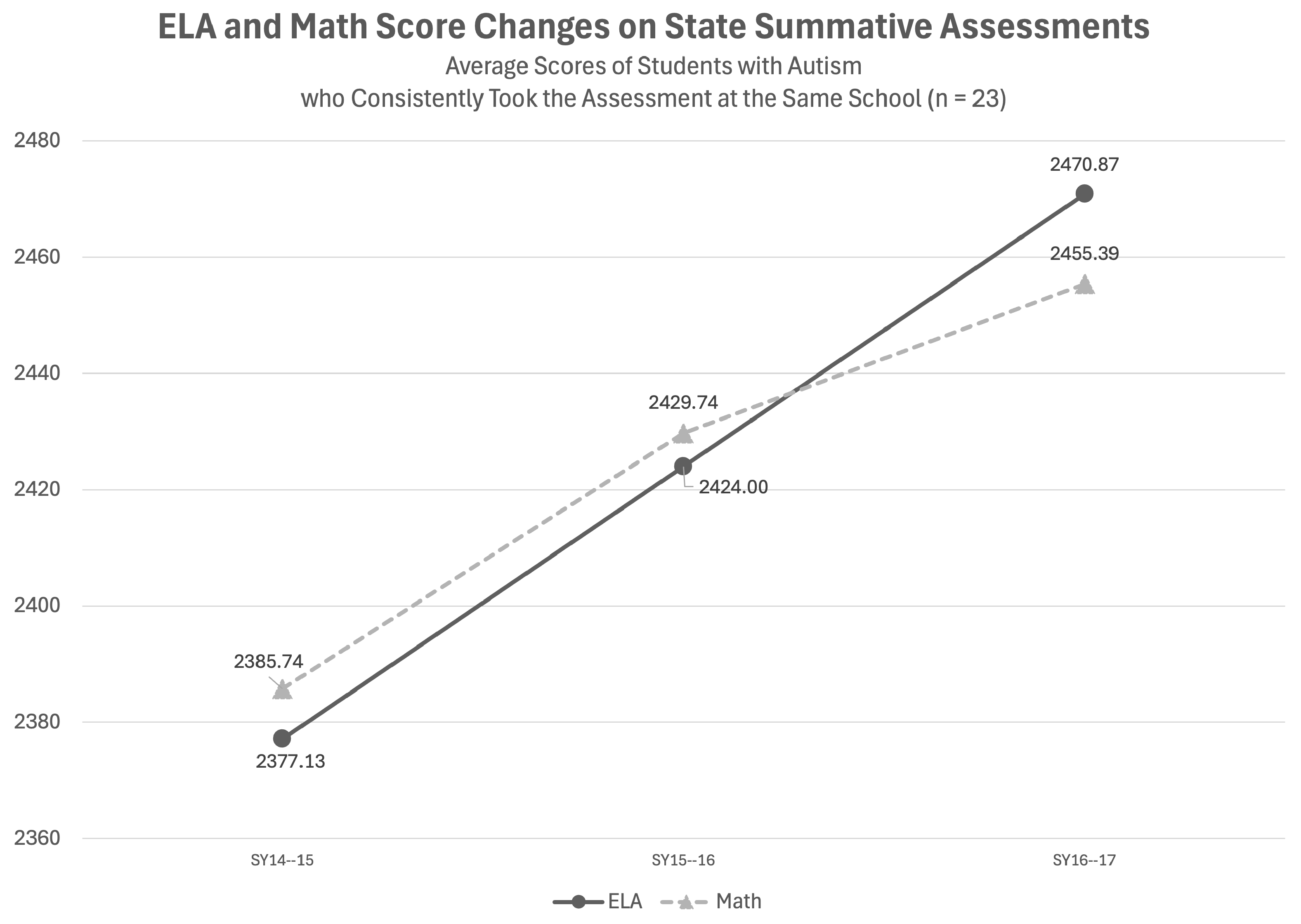

| Year | N | Mean | Standard Dev. | Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELA | SY14–15 | 23 | 2377.13 | 61.10 | 3733.48 |

| SY15–16 | 23 | 2424.00 | 73.50 | 5402.36 | |

| SY16–17 | 23 | 2470.87 | 86.47 | 7477.57 | |

| Math | SY14–15 | 23 | 2385.74 | 70.67 | 4994.47 |

| SY15–16 | 23 | 2429.74 | 62.88 | 3954.20 | |

| SY16–17 | 23 | 2455.39 | 83.90 | 7039.07 |

| Source | Partial SS | df | MS | F | Sig. (p-Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELA | time (year) | 101,050.78 | 2 | 50,525.39 | 30.03 | 0.00 |

| studentID | 291,474.67 | 22 | 13,248.85 | 7.88 | 0.00 | |

| Residual | 74,020.55 | 44 | 1682.29 | |||

| Math | time (year) | 57,081.86 | 2 | 28,540.93 | 21.82 | 0.00 |

| studentID | 294,173.54 | 22 | 13,371.52 | 10.22 | 0.00 | |

| Residual | 57,556.81 | 44 | 1308.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, J.H.; Miller, D.D.; McCart, A.B. Outcomes of Equity-Based Multi-Tiered System of Support and Instructional Decision-Making for Autistic Students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070708

Choi JH, Miller DD, McCart AB. Outcomes of Equity-Based Multi-Tiered System of Support and Instructional Decision-Making for Autistic Students. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(7):708. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070708

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Jeong Hoon, Dawn D. Miller, and Amy B. McCart. 2024. "Outcomes of Equity-Based Multi-Tiered System of Support and Instructional Decision-Making for Autistic Students" Education Sciences 14, no. 7: 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070708

APA StyleChoi, J. H., Miller, D. D., & McCart, A. B. (2024). Outcomes of Equity-Based Multi-Tiered System of Support and Instructional Decision-Making for Autistic Students. Education Sciences, 14(7), 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070708