Principal Attitudes towards Out-of-Field Teaching Assignments and Professional Learning Needs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- What attitudes do principals in Australia and Germany hold towards teacher suitability for out-of-field teaching?

- (2)

- Which professional learning support structures do principals in Australia and Germany consider relevant for out-of-field teachers?

- (3)

- How are teacher support structures related to these attitudes?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Leadership Practices and the Out-of-Field Phenomenon

2.2. Principal Attitudes and Support Structures

3. Methodology

3.1. Our Study

3.2. Design

3.3. Participants and Case Study Selection

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. School Leader Attitudes towards Teaching Out-of-Field

4.1.1. Pedagogical

Content knowledge is just one element of being a teacher… I think there can be danger in looking for someone who’s won a Nobel peace prize for Physics and thinking they are going to be a great Physics teacher… It’s how you can share the love of that subject with the kids and understand that the kids don’t love it as much as you and know it doesn’t come as easy to them either. It’s a relationship game.(Case 6)

4.1.2. Passion

4.1.3. Capability

4.1.4. Specialized

4.2. Support Structures

4.2.1. Collegial Structures

There’s always going to be a Maths/Science person in the teaching team so if they’re teaching out-of-field in those two areas, they’ve got a buddy…Team teaching gives first- and second-year teachers the opportunity to work with an expert.(Case 6)

4.2.2. Mentoring and Coaching

4.2.3. Reflection on Practice

4.2.4. External Support

Our professional development is more aligned to our visions and our strategic directions rather than their qualification…my first question will be, does it relate to our school plan?(Case 5)

Anything that comes across the PD desk gets passed on and they’re really good at this place. If you want to go out on PD and so long as it’s reasonable, you’re not out every single week, you get to go.(Case 6)

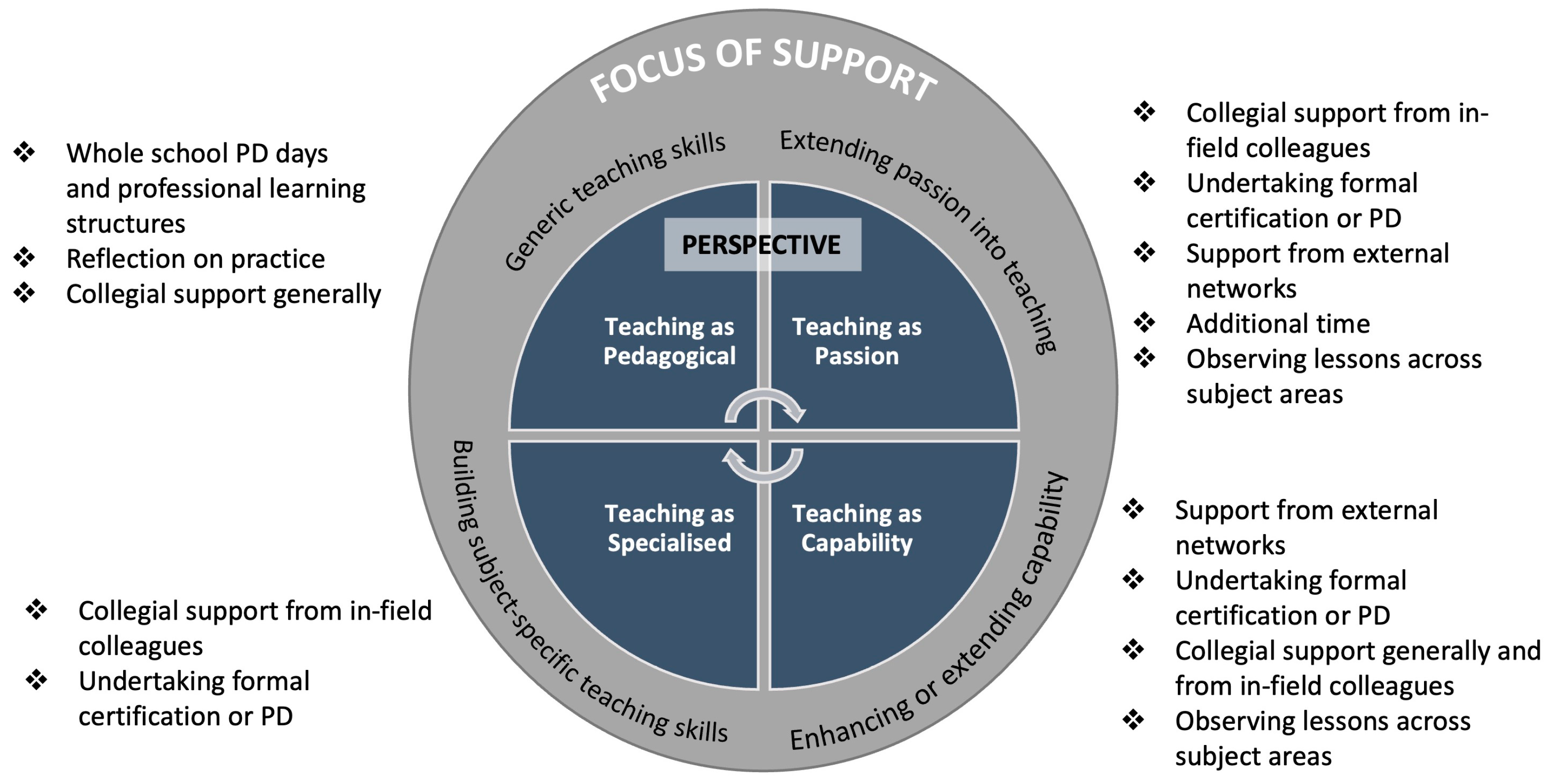

4.3. Typology of Principals’ Perspectives on Out-of-Field Teaching, Quality Teaching and Supports

4.3.1. Teaching as Pedagogical

4.3.2. Teaching as Passion

4.3.3. Teaching as Capability

4.3.4. Teaching as Specialized

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ingersoll, R.M. The problem of out-of-field teaching. Phi Delta Kappan 1998, 79, 773–776. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, L.; Du Plessis, A.; Oates, G.; Caldis, S.; McKnight, L.; Vale, C.; O’Connor, M.; Rochette, E.; Watt, H.; Weldon, R.; et al. Australian National Summit on Teaching Out-of-Field: Synthesis and Recommendations for Policy, Practice and Research. 2022. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57f5c6e0414fb53f7ae208fc/t/62b91e6f96a09659f90a3b79/1656299310264/TOOF-National-Summit-Report.doc (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Price, A.; Vale, C.; Porsch, R.; Luft, J.A. Teaching Out-of-Field Internationally. In Examining the Phenomenon of “Teaching Out-of-Field”: International Perspectives on Teaching as a Non-Specialist; Hobbs, L., Törner, G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.P.; Lee, L.C. Novice School principals’ sense of ultimate responsibility: Problems of practice in transitioning to the principals’ office. Educ. Admin. Quart. 2014, 50, 431–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, L.; Porsch, R. (Eds.) Out-of-Field Teaching across Teaching Disciplines and Contexts; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, C. Supporting out-of-field teachers of secondary mathematics. Aust. Math. Teach. 2010, 66, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, L. Learning to teach science out-of-field: A spatial-temporal experience. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2020, 31, 725–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, L. Teaching ‘out-of-field’ as a boundary-crossing event: Factors shaping teacher identity. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2013, 11, 271–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P. Professional development as a critical component of continuing teacher quality. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2008, 33, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkerman, S.F.; Bakker, A. Boundary crossing and boundary objects. Rev. Educ. Res. 2011, 81, 132–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, A.E.; Carroll, A.; Gillies, R.M. Understanding the lived experiences of novice out-of-field teachers in relation to school leadership practices. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 43, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, A.E. Out-of-Field Teaching: What Leaders Should Know; Sense: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, M.; Finch, M.A. Staffing the classroom: How urban principals find teachers and make hiring decisions. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2015, 14, 12–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, L.; Törner, G. Teaching out-of-field as a phenomenon and research problem. In Examining the Phenomenon of “Teaching Out-of-Field”: International Perspectives on Teaching as a Non-Specialist; Hobbs, L., Törner, G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharplin, E.D. Reconceptualising out-of-field teaching: Experiences of rural teachers in Western Australia. Educ. Res. 2014, 56, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacabey, M.F. School principal support in teacher professional development. Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Manag. 2021, 9, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Crespo, S.; Gairín Sallán, J. School principals’ actions to promote informal learning among teaching staff. Teach. Develop. 2023, 27, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.K.; Nelson, B.S. Leadership Content Knowledge. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2003, 25, 423–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredeson, P.V. The school principal’s role in teacher professional development. J. Serv. Educ. 2000, 26, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabhani, M.; O’Day, N.M.; Bahous, R. Principals’ views on teachers’ professional development. Prof. Develop. Educ. 2014, 40, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpendale, J.; Hume, A. Investigating practising science teachers’ pPCK and ePCK development as a result of collaborative CoRe design. In Repositioning Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Teachers’ Knowledge for Teaching Science; Hume, A., Cooper, R., Borowski, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL]. Australian Professional Standard for Principals and the Leadership Profiles; AITSL: Melbourne, Australia, 2014; Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Hayes, D.; Christie, P.; Mills, M.; Lingard, B. Productive leaders and productive leadership: Schools as learning organisations. J. Educ. Admin. 2004, 42, 520–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, C.; Richardson, P.W.; Watt, H.M.G.; Rice, S. ‘Out-of-field’ teaching in mathematics: Australian evidence from PISA 2015. In Out-of-Field Teaching across Teaching Disciplines and Contexts; Hobbs, L., Porsch, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 71–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Overschelde, J.P. Value-lost: The hidden cost of teacher misassignment. In Out-of-Field Teaching across Teaching Disciplines and Contexts; Hobbs, L., Porsch, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berliner, D.C. The near impossibility of testing for teacher quality. J. Teach. Educ. 2005, 56, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.A.; Aitken, R.; Jantzi, D. Making Schools Smarter. Leading with Evidence; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M.A.; Vaughan, G.M. Social Psychology; Prentice Hall: Sydney, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. The Effect of Principal Leadership on Student Achievement: A Multivariate Meta-Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.; Du Plessis, A.E. Understanding principals’ attitudes towards inclusive schooling. J. Educ. Admin. 1997, 35, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnukainen, M. Inclusion, integration, or what? A comparative study of the school principals’ perceptions of inclusive and special education in Finland and in Alberta, Canada. Dis. Soc. 2015, 30, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhoof, J.; Vanlommel, K.; Thijs, S.; Vanderlocht, H. Data use by Flemish school principals: Impact of attitude, self-efficacy and external expectations. Educ. Stud. 2014, 40, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsch, R.; Whannell, R. Out-of-field teaching affecting students and learning: What is known and unknown. In Examining the Phenomenon of “Teaching Out-of-Field”: International Perspectives on Teaching as a Non-Specialist; Hobbs, L., Törner, G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, A.E. Understanding the Out-of-Field Teaching Experience. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Australia, 2013. Available online: http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:330372/s4245616_phd_submission.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Blackmore, J.; Hobbs, L.; Rowlands, J. Aspiring teachers, financial incentives, and principals’ recruitment practices in hard-to-staff schools. J. Educ. Policy 2023, 39, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donista-Schmidt, S.; Zuzovsky, R.; Arvis Elyashiv, R. First-year out-of-field teachers: Support mechanisms, satisfaction and retention. In Out-of-Field Teaching across Teaching Disciplines and Contexts; Hobbs, L., Porsch, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, F.; Kenny, J.; Campbell, C.; Crisan, C. Teacher learning and continuous professional development. In Examining the Phenomenon of “Teaching Out-of-Field”: International Perspectives on Teaching as a Non-Specialist; Hobbs, L., Törner, G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 269–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Creating Effective Teaching and Learning Environments: First Results from TALIS; OECD: Paris, France, 2009; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/creating-effective-teaching-and-learning-environments_9789264068780-en (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Du Plessis, A.E.; Hobbs, L.; Luft, J.A.; Vale, C. The out-of-field teacher in context: The impact of the school context and environment: International perspectives on teaching as a non-specialist. In Examining the Phenomenon of “Teaching Out-of-Field”: International Perspectives on Teaching as a Non-Specialist; Hobbs, L., Törner, G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Porsch, R.; Hobbs, L. Initial teacher education: Roles and possibilities for preparing capable teachers. In Examining the Phenomenon of “Teaching Out-of-Field”: International Perspectives on Teaching as a Non-Specialist; Hobbs, L., Törner, G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Fransisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fylan, F. Semi-structured interviewing. In A Handbook of Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology; Miles, J., Gilbert, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Multiple Case Study Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kelle, U.; Kluge, S. Vom Einzelfall zum Typus. Fallvergleich und Fallkontrastierung in der Qualitativen Sozialforschung; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, J.M.; Bowe, J.M. Interrupting attrition? Re-shaping the transition from preservice to inservice teaching through Quality Teaching Rounds. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 73, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L.S.; Sherrin, M.G. Fostering communities of teachers as learners: Disciplinary perspectives. J. Curric. Stud. 2004, 62, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosswell, L.; Elliott, B. Committed teachers, passionate teachers: The dimension of passion associated with teacher commitment and engagement. In AARE Conference 2004; Jeffrey, R., Ed.; Australian Association for Research in Education: Melbourne, Australia, 2004; pp. 1–12. Available online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/968/ (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Hobbs, L.; Quinn, F. Out-of-field teachers as learners: Influences on teacher perceived capacity and enjoyment over time. Europ. J. Teach. Educ. 2021, 44, 627–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C. A Passion for Teaching; Routledge: Harvard, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Heikonen, L.; Pertarinen, J.; Pyhältö, K.; Toom, A.; Soini, T. Early career teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom: Associations with turnover intentions and perceived inadequacy in teacher-student interaction. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 45, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, P.R. Out-of-Field Teaching in Australian Secondary Schools; Australian Council for Educational Research: Melbourne, Australia, 2016; Available online: https://research.acer.edu.au/policyinsights/6/ (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Prince, G.; O’Connor, M. Crunching the Numbers on Out-of-Field Teaching; Australian Mathematical Science Institute: Parkville, Australia, 2018; Available online: https://amsi.org.au/media/AMSI-Occasional-Paper-Out-of-Field-Maths-Teaching.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Richter, D.; Pant, H.A. Lehrerkooperation in Deutschland, Eine Studie zu Kooperativen Arbeitsbeziehungen bei Lehrkräften der Sekundarstufe I. Bertelsmann Stiftung, Deutsche Telekom Stiftung, Robert Bosch Stiftung, Stiftung Mercator. 2016. Available online: https://www.bosch-stiftung.de/de/publikation/lehrerkooperation-deutschland (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Ziegler, C.; Richter, D. Der Einfluss fachfremden Unterrichts auf die Schülerleistung: Können Unterschiede in der Klassenzusammensetzung zur Erklärung beitragen? Unterrichtswissenschaft 2017, 45, 136–155. [Google Scholar]

- Porsch, R. Fachfremd unterrichten in Deutschland. Definition—Verbreitung—Auswirkungen. Die Dtsch. Sch. 2016, 108, 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, K.L.; Jensz, F. The Preparation of Mathematics Teachers in Australia. Meeting the Demand for Suitably Qualified Mathematics Teachers in Secondary Schools; Australian Council of Deans of Science: Parkville, Australia, 2024; Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/3423 (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Productivity Commission. Review of the National School Reform Agreement; Study Report; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2022. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/school-agreement/report (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Guramatunhu-Mudiwa, P.; Scherz, S.D. Developing psychic income in school administration: The unique role school administrators can play. Educ. Manag. Admin. Lead. 2013, 41, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | Country/State | Key Features | Interviewees |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Germany/North-Rhine-Westphalia | Regional, large school for years 5 to 13, “Gesamtschule” | Principal |

| 2 | Germany/North-Rhine-Westphalia | Metropolitan, medium school for years 5 to 10, “Realschule” | Principal |

| 3 | Germany/North-Rhine-Westphalia | Regional, medium school for years 5 to 10, “Realschule” | Deputy principal |

| 4 | Germany/Lower Saxony | Metropolitan (located on the outskirts), medium school for years 5 to 10, “Oberschule” | Principal |

| 5 | Australia/New South Wales | Rural, small school for years 7–12 | Principal |

| 6 | Australia/Victoria | Regional, medium school for years Prep-12, year 7 and 8 structured as team teaching in core subjects (Maths, English, Science, Humanities) | Deputy Principal |

| 7 | Australia/Victoria | Rural, small school for years Prep-12, offers core units plus student electives, units taught as two-year levels, e.g., years 7 and 8 classes due to small size | Principal |

| 8 | Australia/New South Wales | Rural, small school for years Prep-12, small number of teachers, distance education used for senior classes | Principal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Porsch, R.; Hobbs, L. Principal Attitudes towards Out-of-Field Teaching Assignments and Professional Learning Needs. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070783

Porsch R, Hobbs L. Principal Attitudes towards Out-of-Field Teaching Assignments and Professional Learning Needs. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(7):783. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070783

Chicago/Turabian StylePorsch, Raphaela, and Linda Hobbs. 2024. "Principal Attitudes towards Out-of-Field Teaching Assignments and Professional Learning Needs" Education Sciences 14, no. 7: 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070783