Abstract

Collaborative learning (CL) is the instructional use of small groups in such a way that students work together to maximize their own and others’ learning. In this study, the aim was to implement online collaborative learning (OCL) using the Microsoft Teams (MT) platform and to analyze the students’ preferences regarding presential or online learning. Material and Methods: A descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study was conducted with 79 students from the Degree in Dentistry. Four groups were created with MT and clinical cases or problems were uploaded for online discussion with each group. Additionally, as part of the course program, the students were divided into the same groups for to carry out Problem-Based Learning (PBL) in person. Afterwards, students completed a project assessment and satisfaction survey. Results: The survey revealed that the students found participation in this project to be useful or very useful. Their experiences with MT were rated as positive or very positive. However, a significant portion of the students (42.6%) preferred conventional face-to-face (FF) problem-solving, while 27.9% preferred using online tools. Based on the execution of this project and the open feedback on the use of MT, we have outlined a series of recommendations to enhance the use of this platform. Conclusions: MT is a highly useful platform for online teaching, offering multiple tools to promote learning in a virtual and asynchronous manner. However, when comparing CL through PBL conducted FF versus online, students still prefer in-person teaching to virtual methods.

1. Introduction

Collaborative learning (CL) is an educational approach where small groups of students work together to enhance both their individual learning and that of their peers [1]. This pedagogical method complements learning efforts, emphasizing shared responsibility in understanding and mastering content. These pedagogical strategies encourage students to engage collectively in comprehending material, ensuring accountability for their own and their peers’ educational progress [1]. These strategies include diverse techniques to facilitate group interaction, allowing members to share, expand, and deepen their knowledge on specific subjects [1]. Unlike task division, CL involves each participant contributing valuable insights to enhance the group’s collective understanding [2]. This dynamic process includes the exchange of supplementary information, clarifications, and opportunities to correct or refine contributions [2]. Consequently, CL should be viewed as an interactive educational process, fostering mutual teaching and learning, rather than merely a summation of individual inputs [2]. Due to its numerous benefits, CL has been applied across various branches of dentistry, including conservative dentistry [3], introductory courses to the dental clinic, and introduction to periodontics [4]. This learning methodology has been concurrently implemented among dental and hygiene students, yielding satisfactory results and promoting multidisciplinary team learning aimed at enhancing professional practice. It has been observed that this type of learning fosters a positive perception of other dental specialties among students, improves their problem-solving skills, and enhances their ability to work effectively in teams [4].

In 1980, Barrows and Tamblyn [5] described a new CL method, the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) model as “a learning that results from the process of working toward understanding or resolution of a problem.” The problem serves as a stimulus, facilitating the connection between fundamental knowledge and its clinical application. PBL also promotes CL within small groups. Its application in fields such as dentistry has been demonstrated to enhance students’ ability to apply their knowledge to clinical scenarios [6]. According to students, PBL enhances their preparedness for patient care [7]. Furthermore, students report improvements in patient communication, development of critical thinking, and enhanced teamwork [8,9,10].

Conversely, online training, facilitated by the burgeoning use of new Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), has expanded the range of possibilities for developing a hybrid learning environment that integrates both remote and face-to-face (FF) interactions. Evidence suggests that appropriately utilized ICTs can promote and enhance CL, which subsequently has a positive impact on professional careers [11]. Microsoft Teams (MT) is a digital communication platform that enables virtual meetings, chatting, file storage, and file sharing, and integrates applications such as Forms, PDF, PowerPoint, Wiki, Excel, and Edpuzzle, among others [12]. In the literature, it is stated that MT is user-friendly and has comprehensive features, such as information sharing, online meetings, and asynchronous discussions, all while maintaining necessary social distancing during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic [13]. Moreover, on top of all these benefits, MT is integrated into multiple university online platforms, such as Moodle. Due to this, it is necessary to conduct a study that analyzes student satisfaction and/or perception with CL using MT in the Degree of Dentistry.

For the development of this research, we applied the collaborative-teaching methodology in an online format (OCL). As some authors suggest, collaborative tools should emphasize aspects such as reasoning, self-learning, and CL [1]. The MT platform has been extensively used by educators for teaching classes, seminars, and other training activities [13,14,15,16]. Although online CL has multiple benefits over traditional learning, it also has disadvantages, like the necessity of a personal computer and Internet connection, communication problems between students and professors, etc. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, hybrid learning has increased, but it is necessary to know students’ perceptions. The study question was “Is student perception of OCL better than the conventional learning method?” The hypothesis was that online CL improves students’ perception compared with traditional method. A pilot study was designed to obtain preliminary preference data. The main aim of this study was to implement OCL learning using the MT platform. The specific objectives were the following: (1) to reinforce the knowledge acquired in the theoretical teaching of the Pediatric Dentistry II course in the fourth year of the Dental Degree, (2) to evaluate students’ assessment of this teaching method and the platform used, and (3) to compare students’ perceptions and satisfaction of learning between OCL with MT and face-to-face collaborative learning (FFCL) through PBL.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants and Study Design

A descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study was conducted with 4th-year dentistry students enrolled in the Pediatric Dentistry II course at the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM). The sampling method was non-probabilistic, inviting to participate all students enrolled in the subject mentioned above (n = 79). Students repeating the subject, or who rejected participation were excluded. Finally, 76 students accepted participation and 68 completed the survey. Post-hoc goodness-of-fit for contingence tables was calculated (G*Power version 3.1.9.7.), with an alpha error of 0.05 and effect size of 0.5, the power of the study was 94.79%. This research project is part of the UCM Educational Innovation Projects. Ethical approval was granted by the Vice-Rectorate of Quality at the UCM (Registration number 147) on July 23, 2021. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study.

In this study, MT was chosen to implement CL in the Pediatric Dentistry II course by forming groups. This platform was selected due to its availability through the Moodle of the UCM. For the development of this research, four random groups were created within MT, according to the clinical practice groups, accessible through the UCM Moodle. The rationale behind forming smaller groups was to enhance student participation, which is crucial for effective CL. The four teams were composed of 22 students each in Teams 1 and 2, 19 students in Team 3, and 16 students in Team 4. Each group was supervised by two professors. All professors were calibrated in the clinical cases used in the project, with theorical and practical sessions. Teams 1 and 2 received case explanations directly from the professors, whereas Teams 3 and 4 did not receive in-person explanations; instead, the cases were uploaded to MT for their review. This design aimed to determine whether in-person case explanations are necessary or if uploading the cases to MT alone is sufficient for student understanding and engagement.

Synchronous with the theoretical teaching, clinical cases or problems were uploaded to be discussed online within each group. A total of six clinical cases or problems were uploaded: the first week covered “Physiological Resorption of Lower Primary Incisors”, the second week addressed “Enamel Demineralization”, the third week focused on “Dental Union Alterations”, the fourth week dealt with “Harmful Habits: Atypical Swallowing”, the fifth week examined “Dental Traumatology”, and the sixth week covered “Infectious Pathology and Space Maintenance”. Additionally, as part of the course program, students were divided into the same teams for several weeks of classroom-based Problem-Based Learning (PBL). The PBL consisted of the online upload of the case that was assigned that week, and the discussion between the students in the forum, in which the professor served as moderator. Therefore, following the PBL philosophy, information was added to the initial case to advance in the knowledge of the case, and outline the outcome.

After finishing the project, an assessment and satisfaction survey was completed by the participating students. The survey was designed to be anonymous to eliminate bias. Prior to the start of the study, the survey was created and tested by professors of the subject, giving their feedback independently to solve possible language and comprehension errors. The questionnaire on student satisfaction and perception was divided into five main blocks. The first block, which assessed the students’ satisfaction with the project, consisted of four questions. The possible answers were on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 was not very useful and 5 was very useful. In the second block, the six cases proposed to develop the activity were evaluated and consisted of another four questions. Students had to choose the case with which they had learned the most and the least. In the third block, students evaluated MT, consisting of seven questions. The possible answers to the questions in this third block were on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 was very negative and 5 was very positive. The fourth block was a single open question: “What would you change or add to Collaborative Learning with MT?”. And the last block compared FFCL with OCL and consisted of two questions, where students had to answer which mode they liked more and with which mode they learned more.

A statistical analysis was carried out with IBM SPSS 24 software. A descriptive analysis was performed with frequencies and percentages. The data were subjected to an inferential statistical analysis to analyze whether the group of practices influenced the preferences and learning reported by the students, obtained in the anonymous survey, using Chi-square tests with asymptotic significance (bilateral) or Fisher’s exact test, depending on the characteristics of the sample distribution. In all cases, a confidence level of 95% (p < 0.05) was used. Significance was asymptotic or bilateral for the Chi-square (χ2) test and exact significance for Fisher’s test.

3. Results

Of the 79 students enrolled in the course, 76 participated voluntarily; the distribution of students in each work group is detailed in Table 1. The participation rate was 96.20%, with 68 students completing the satisfaction survey (86.18% of those enrolled, 89.47% of participants) and included in the study. There was a significant imbalance in gender distribution among the students, with 79.4% being female and 20.6% male (χ2 p < 0.001). Regarding age, 92.6% of students were under 25 years old, 5.9% were aged between 25 and 30 years, and 1.5% were over 30 years old, showing a non-homogeneous age distribution (χ2 p < 0.001). The researchers concluded that neither sex nor age significantly affected the students’ teaching preferences. The number of interventions or responses in each team was as follows: group 1 had 150 interventions, group 2 had 133 interventions, group 3 had 280 interventions, and group 4 had 161 interventions. As a personal perception, it appears that groups 1 and 2, where cases were explained in person beforehand, showed considerably less interest in participating compared to groups 3 and 4.

Table 1.

Sample distribution.

The distribution of students in the four study groups was homogeneous (p-χ2 = 0.623). Depending on the teaching model, the distribution was also homogeneous; groups 1 and 2 (48.5%) corresponded to groups to which teachers explained the cases, while groups 3 and 4 (51.4%) were groups to which an explanation was not offered.

The results obtained in the satisfaction survey are presented in Table 2. A total of 76.48% of the students found participation in the project useful or very useful, regardless of their group (Fisher p = 0.595). A total of 86.76% of the students reported achieving positive or very positive learning outcomes with the project, and 75% expressed a satisfaction level between good and very good (Fisher p = 0.954 and Fisher p = 0.533, respectively). Only four students (5.9% of the sample) considered it useless or not very useful. Regarding learning (question number 2), 85.9% indicated that they learned a lot or a great deal. Similarly, positive results were obtained for question 3 regarding satisfaction with participation in the project. Nearly 80% expressed willingness to participate again, with only 5% indicating they would not participate again. Therefore, based on our analysis of the successful implementation of online CL, we can conclude that it has been highly satisfactory.

Table 2.

Satisfaction survey and results in overall sample expressed in number of answers and percentage for each question. Educational Innovation Project (EIP); Microsoft Teams (MT); Online Collaborative Learning (OCL); Face-to-Face Collaborative Learning (FFCL).

Of the cases uploaded, the one that stood out the most due to its interest and the perceived learning impact by the students was the dental traumatology case. Regarding the use of MT (questions 9 to 15), overall, the responses were positive or very positive across all aspects analyzed. Notably, in question 9, 42.6% found their experience with the platform very positive, and 26.5% found it positive. Similarly, in question 10 regarding the management of MT, there were high percentages of positive or very positive responses. The aspect where there was the most disagreement was whether the platform promotes case participation, with 22.6% believing it does not. Analyzing the responses to question 15, which evaluates the overall experience of online CL using MT, 78% rated it positively.

Regarding the results obtained from open question 16, the professors involved in the project compiled a document outlining improvements and recommendations for utilizing the MT platform as a tool for virtual CL. Among the responses received for this question, 15 students indicated they would not change anything. Positive responses highlighted the platform’s interactivity and suggested uploading more cases to strengthen learning and concepts. Additionally, suggestions included implementing a voting system for best answers to further encourage participation.

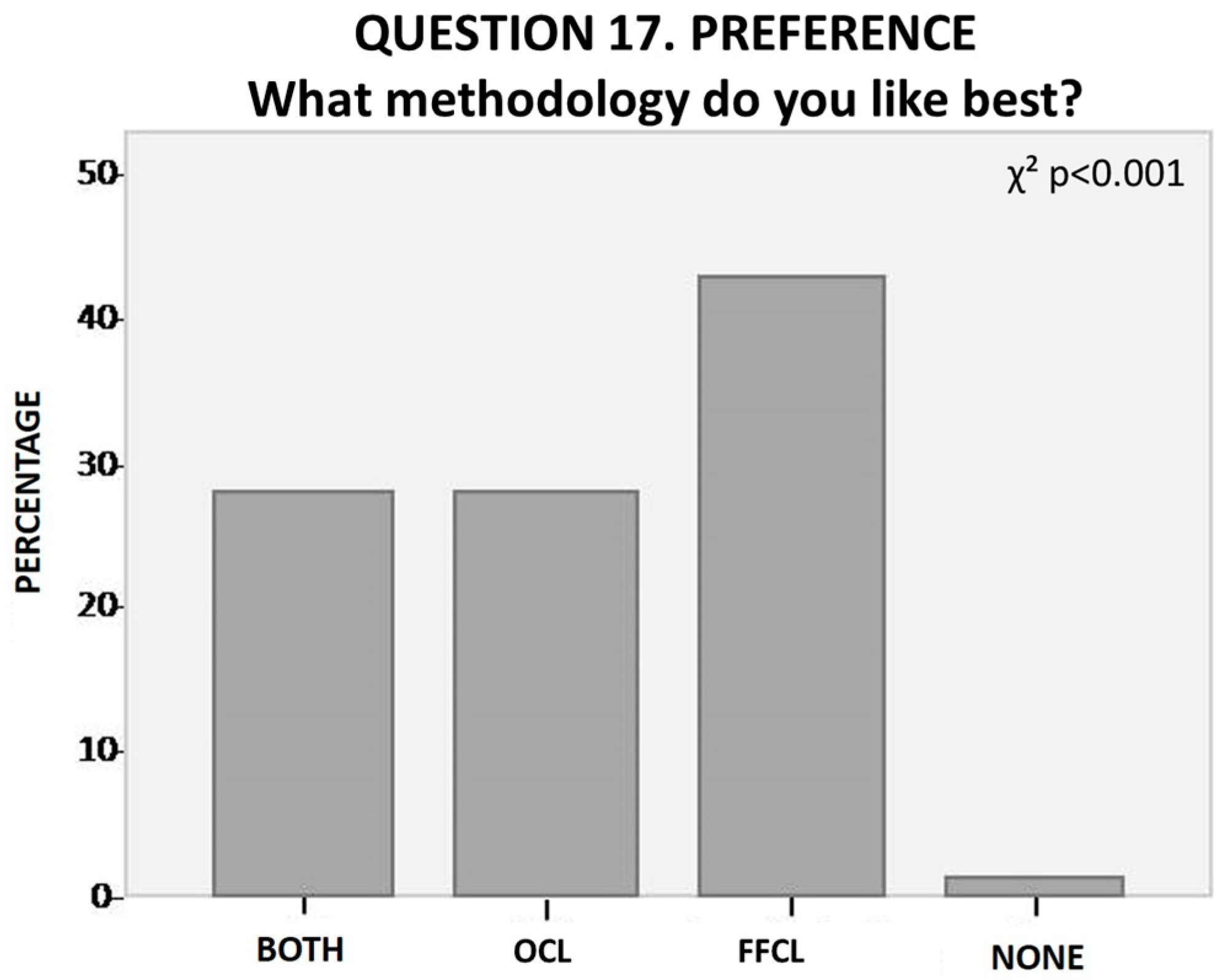

Students showed a preference for conventional FF problem solving (42.6%), while 27.9% favored the use of online tools such as MT. Another 27.9% indicated a preference for both learning methods, while only 1.5% preferred neither method (χ2 p < 0.001) (Figure 1). We also examined whether the internship group significantly influenced the preference for class type, but found no significant differences among the four study groups (Fisher p = 0.538). Teaching method does not affect the preference comparing conventional and online methodology.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the percentage of preference of the learning methodology. OCL: online collaborative learning. FFCL: face-to-face collaborative learning.

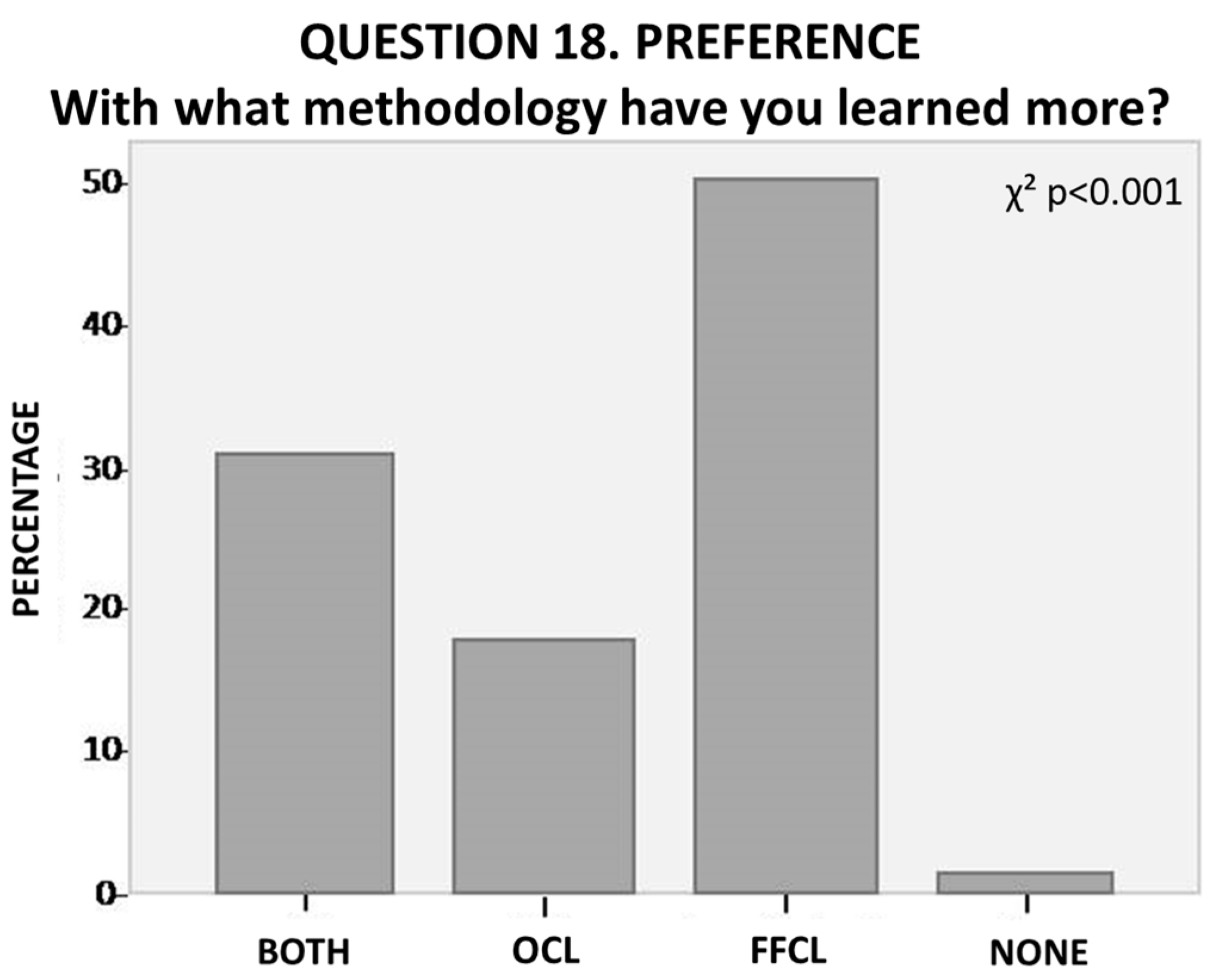

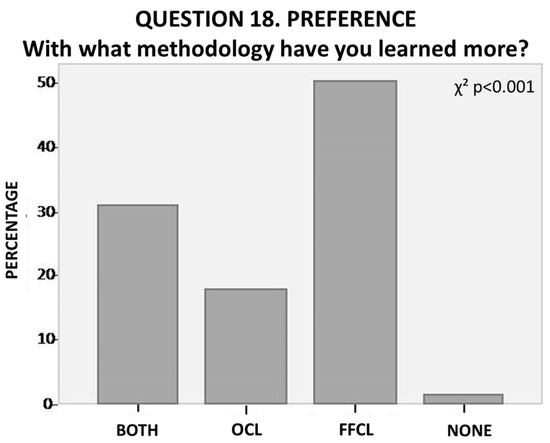

Related to the learning amount, half of the students (50%) reported that they learned more with FF case resolution, while 17.6% indicated they learned more with online learning using MT (Figure 2). There was a significant difference in the students’ learning preferences, with 30.9% stating they learned equally well with both methods, and only 1.5% indicating they learned from neither method (χ2 p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Graphic representation of the feeling of greater learning obtained by the students. OCL: online collaborative learning. FFCL: face-to-face collaborative learning.

We also examined whether the clinical practice group significantly influenced the perception of greater learning, but found no significant differences among the four study groups (Fisher p = 0.899). Additionally, we analyzed whether explaining the cases beforehand (groups 1 and 2) influenced students’ perception of learning compared to those who did not receive prior explanation (groups 3 and 4), and found that the differences were not statistically significant (χ2 p = 0.310). In both groups (with and without prior explanation), students reported learning more with the FFCL method (48.48% and 51.42%, respectively) compared to MT (24.24% and 11.42%, respectively), with the difference being more pronounced in the group without prior explanation.

4. Discussion

Nowadays, online learning has emerged as a viable option for millions of individuals due to its flexibility, accessibility to high-quality education, and numerous other advantages [17]. It has gained significant traction over traditional FF education, especially in the aftermath of the global COVID-19 pandemic, prompting many students to explore its benefits.

While the Dentistry Degree program heavily relies on practical hands-on training that is essential and cannot be replaced by distance learning, master classes, seminars, and certain preclinical practices can effectively be integrated into online modalities. This integration allows for a simultaneous approach to teaching and learning. It is crucial to note, however, that clinical education in dentistry remains inherently FF in nature [18].

Authors like Jackson et al. successfully implemented CL among dental and oral hygiene students, achieving satisfactory results. Their approach aimed at fostering multidisciplinary team learning to enhance professional practice. The study noted positive impacts such as improved attitudes towards other dental professions, enhanced problem-solving abilities, and strengthened teamwork skills [4].

Collaborative learning can effectively utilize problem-solving methodologies. Problem-Based Learning aligns with modern educational principles such as constructive, self-directed, collaborative, and contextual learning [19]. This type of pedagogical methodology, PBL, is well established and integrated in dental curricula such as at the University of Iowa [20]. Puranik et al. conducted a study applying PBL in pediatric dentistry, revealing that this teaching method improved students’ technical skills, increased pass rates, and enhanced students’ self-perception of their learning experience [6]. The latter authors also applied the PBL methodology in cases of dental trauma and concluded that this methodology has a positive impact on students‘ learning [10]. In other areas of health sciences, such as nursing, it has been concluded in a meta-analysis that Problem-Based Learning helps to improve students’ critical thinking [9].

Chirravur et al. applied OCL in oral medicine and conducted a satisfaction survey, yielding highly positive outcomes [14]. Similarly, during the pandemic, authors like Jabbour and Tran implemented OCL, achieving favorable results. They emphasized that while OCL enhances student preparation and subsequent clinical performance, it does not substitute FF teaching in clinical settings where patient interaction is essential [21].

In our study, implementing online CL through PBL showed satisfactory outcomes. However, when comparing the same methodology in online versus FF formats, related to the professors’ explanation prior to PBL, students expressed a preference for FF problem explanation, as they perceive greater learning efficacy in that setting.

Henderson et al. utilized MT to educate and reinforce knowledge among non-specialist physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic, including dermatologists, hematologists, histopathologists, neurologists, and ophthalmologists. They concluded that training through this platform was accessible and well-received [13]. Chan and Lee employed MT alongside Zoom during the pandemic to facilitate communication between teachers, students, and patients, with satisfactory outcomes [15]. Plata-Gomez and González-Jiménez utilized MT for teaching in both medicine and law degrees, encountering minimal difficulties and recommending the platform for educational use [16]. These findings align with our study, where the use of MT was perceived positively across various aspects analyzed. MT has also demonstrated effectiveness in non-medical disciplines like law as an innovative tool in higher education [22].

Di Carvalho et al. conducted a review aimed at assessing the prevalence of various teaching methodologies and platforms utilized in dental education. According to their findings, Zoom was the most commonly used platform, accounting for 70.6% of cases, followed by MT at 23.5%. This review highlighted the promising integration of non-presential teaching methodologies and platforms within dental education [23].

Based on our analysis, the results of using MT for online team formation and problem-solving have generally been positive, according to previous literature [24,25], showing a greater satisfaction with a hybrid learning model compared to the conventional method. However, despite these favorable outcomes, when compared to FF methods, students still prefer the traditional FF approach. This preference may be due to the fact that our students were accustomed to in-person teaching before the pandemic. Therefore, it would be highly interesting to replicate this study in the future, when online teaching methods have become more established in our specialty. This would allow us to observe if attitudes towards online learning have shifted over time. Additionally, in analyzing the level of participation, we found it intriguing that groups where cases were not explained beforehand in person showed more interest. This is contrary to our initial expectation that in-person explanations would encourage greater participation. This observation suggests that remote learning methodologies, such as the one we employed, can effectively stimulate student engagement in case discussions. Overall, while students still prefer FF learning for problem-solving, our findings indicate that online CL-using platforms like MT hold promise for enhancing participation and engagement in dental education.

Based on the feedback and open answers from question 16, the professors involved in our project collectively identified several key recommendations to enhance the use of MT as a platform for CL:

- FF Explanation: Always provide an FF explanation to students on how to use the MT platform. This ensures clarity and understanding of its functionalities before starting any collaborative activities.

- Introductory Video or Presentation: Alternatively, provide an introductory video or presentation on the MT platform outlining how activities will be conducted and how students should participate. This can be accessible on the platform itself for easy reference.

- Activate Notifications: Emphasize the importance of activating notifications on MT to ensure students receive timely updates on new posts, changes, or responses made by peers and instructors.

- Mobile Application: Encourage students to download the MT mobile application. This facilitates access to the platform and allows for participation even when they are not at their computers.

- File Format Recommendations: When uploading images or other files, recommend using jpg format and organizing them into folders. This makes it easier for students to view and download files, especially if they need to zoom in or have doubts about specific content.

- Supportive Resources: Acknowledge that while CL can be effectively conducted online with MT, some complex issues or questions may require additional support. Establish tutorials or FF sessions where students can seek clarification or deeper explanations beyond online chats.

- Implementing these recommendations aims to optimize the use of MT for CL in dental education, ensuring smoother engagement, effective communication, and enhanced learning outcomes for students.

In our study, we explored whether the practice group influenced students’ preferences for the type of classes, but we did not find statistically significant differences. This finding may not be particularly noteworthy since our results are likely applicable and relevant to other groups of students as well. As previously mentioned, the goal of our research was to implement virtual CL using MT and to assess students’ opinions and their perceptions of their learning outcomes. However, a limitation of our study is that we did not objectively evaluate whether students learned effectively with this method compared to traditional FF teaching. This comparison would be valuable to conduct in future studies, as recommended by authors such as Daisy Henderson et al. [13]. As we pointed out in the methodology, groups 1 and 2 were offered explanations in person about the proposed cases, but groups 3 and 4 were given the cases on MT and had to solve them. We found that there were no differences in the perception of learning among the students in all groups, but we did not analyze the learning itself, as we have already mentioned. Therefore, we believe it would be interesting in subsequent studies to assess whether the teacher’s explanation prior to uploading the cases influences learning. Other factors to take into account are the Hawthorne effect, where our results may have been conditional as students had to give consent to participate in this study, and the “Dunning–Kruger effect” whereby certain individuals with limited knowledge and skills are considered superior to others who are better prepared. For all of the above reasons, we propose a method of objective assessment of learning in future studies. Another possible limitation of our study is the sample, both in terms of its size, as it was limited by the number of students enrolled and their characteristics. Because of this, we were not able to analyze the influence of gender and age of the students on the students’ teaching preferences, as our sample was not homogeneous, being 79.5% female and 92.5% of the sample were students under 25 years of age.

Despite the limitations mentioned above, our study has many strengths, such as having established an OCL model with which students feel they have learned. In addition, with the perception of both students and teachers, we have made a series of recommendations that may help other teachers to implement this online model as a complement to their FF classes.

During the COVID19 pandemic, various platforms, including MT, played a crucial role in continuing our students’ education. Despite their current preference for FF teaching, we believe it would be valuable to revisit this study in the future, once online teaching practices are more established. This could help us understand if current preferences are influenced by the novelty and lack of prior experience with online learning methods. With this publication, we aimed to showcase our project and highlight the numerous possibilities that platforms like MT offer. We find it pertinent to share our findings because they can be applicable across various fields of education and disciplines.

5. Conclusions

We can conclude that online platforms, for example MT, are highly useful methods, not only for online teaching but also for promoting virtual and asynchronous learning using its multiple tools. The use of MT as a platform for promoting CL through problem-solving has been found to be very effective. However, when comparing CL through PBL in FF versus online settings, students still prefer FF teaching over virtual methods. This preference highlights the continued importance of in-person interactions in educational settings, despite the advantages offered by online platforms like MT.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.C., A.M-V. and N.E.G.-L.; methodology, A.M.C., A.M-V. and N.E.G.-L.; software, A.M.C., A.M.-V. and G.F.; validation, M.R.M.-M. and A.M.C.; formal analysis, A.M.C.; M.J.d.N.-G. and N.E.G.-L.; investigation, A.M.C., G.F. and M.R.M.-M.; resources, A.M.C.; data curation, N.E.G.-L.; writing-review editing, G.F. and A.M.C.; visualization, A.M.-V.; supervision, A.M.C. and M.J.d.N.-G.; project administration, A.M.C. and G.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Vice President for Quality of the UCM with reference number 147 for the 2020–2021 call for educational innovation projects at the UCM. It was carried out by professors of Paediatric Dentistry II in the 4th year of the Degree in Dentistry at the UCM.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all students to participate in the study as well as to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (the data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.; Holubec, E.J.; Roy, P. Circles of Learning, 4th ed.; Interaction Book Company: Edina, MN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Carrió Pastor, M.L. Ventajas del uso de la tecnología en el aprendizaje colaborativo. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 2007, 41, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, E.M.; Salmerón, D.; Alonso, A.; Morales-Delgado, N. Aprendizaje colaborativo en odontología conservadora mediante el uso de la lluvia de ideas como recurso educativo. Rev. Esp. Edu. Med. 2020, 1, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.C.; Bilich, L.A.; Skuza, N. The benefits and challenges of collaborative learning: Educating dental and dental hygiene students together. J. Dent. Educ. 2018, 82, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, H.S.; Tamblyn, R.M. Problem-Based Learning: An Approach to Medical Education, 1st ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Puranik, C.P.; Pickett, K.; Randhawa, J.; de Peralta, T. Perception and outcomes after implementation of problem-based learning in predoctoral pediatric dentistry clinical education. J. Dent. Educ. 2022, 86, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassir, S.H.; Sadr-Eshkevari, P.; Amirikhorheh, S.; Karimbux, N.Y. Problem-based learning in dental education: A systematic review of the literature. J. Dent. Educ. 2014, 78, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thammasitboon, K.; Sukotjo, C.; Howell, H.; Karimbux, N. Problem based learning at the Harvard school of dental medicine: Selfassessment of performance in postdoctoral training. J. Dent. Educ. 2007, 71, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.N.; Qin, B.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Mou, S.Y.; Gao, H.M. The effectiveness of problem-based learning on development of nursing students’ critical thinking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puranik, C.P.; Pickett, K.; de Peralta, T. Evaluation of problem-based learning in dental trauma education: An observational cohort study. Dent. Traumatol. 2023, 39, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colorado-Aguilar, B.L.; Edel-Navarro, R. La usabilidad de TIC en la práctica educativa. Rev. Educ. Distancia 2012, 30, 1–11. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/red/article/view/232611 (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Private Channels in Microsoft Teams. Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoftteams/private-channels (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Henderson, D.; Woodcock, H.; Mehta, J.; Khan, N.; Shivji, V.; Richardson, C.; Aya, H.; Ziser, S.; Pollara, G.; Burns, A. Keep calm and carry on learning: Using Microsoft Teams to deliver a medical education programme during the COVID-19 pandemic. Future Healthc. J. 2020, 7, e67–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirravur, P.; Sroussi, H.; Sahni, S. Never waste a crisis: An online collaborative learning module in oral medicine. J. Dent. Educ. 2022, 86, 789–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.K.; Lee, A.L. Teaming up for patient care seminars: Using Microsoft Teams private channels to facilitate HIPAA-compliant small group educational sessions. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 85, 1139–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plata-Gómez, A.B.; González-Jiménez, P.M. Microsoft Teams como experiencia e-learning: Docencia disruptiva para superar una pandemia global. In CIVINEDU 2020, Proceedings of the 4th International Virtual Conference on Educational Research and Innovation, Madrid, Spain, 23–24 September 2020; REDINE, Ed.; Adaya Press: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 449–451. Available online: https://www.civinedu.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/CIVINEDU2020.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Barbour, M.K.; Reeves, T.C. The reality of virtual schools: A review of the literature. Comput. Educ. 2009, 52, 402–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerta Jarama, P.A. La óptima enseñanza en la formación de profesionales cirujanos dentistas en el Perú en tiempos de pandemia. Odontol. Sanmarquina 2020, 23, 357–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolmans, D.H.; De Grave, W.; Wolfhagen, I.H.; van der Vleuten, C.P. Problem-based learning: Future challenges for educational practice and research. Med. Educ. 2005, 39, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, T.A.; Straub-Morarend, C.L.; Handoo, N.; Solow, C.M.; Cunningham-Ford, M.A.; Finkelstein, M.W. Integrating critical thinking and evidence-based dentistry across a four-year dental curriculum: A model for independent learning. J. Dent. Educ. 2014, 78, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbour, Z.; Tran, M. Can students develop clinical competency in treatment planning remotely through flipped collaborative case discussion? Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2023, 27, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, I.; Tapp, D. Teaching with Teams: An introduction to teaching an undergraduate law module using Microsoft Teams. Innov. Pract. High. Educ. 2019, 3, 58–66. Available online: https://journals.staffs.ac.uk/index.php/ipihe/article/view/64/99 (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Di Carvalho Melo, L.; Bastos Silveira, B.; Amorim Dos Santos, J.; Cena, J.A.; Damé-Teixeira, N.; Martins, M.D.; De Luca Canto, G.; Guerra, E.N.S. Dental education profile in COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2023, 27, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.Y.; Puttige Ramesh, N.; Kaczmarek-Stewart, K.; Ahn, C.; Li, A.Z.; Ohyama, H. Dental Student Perceptions of Distance Education over Time: A Mixed-Methods Study. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousry, Y.M.; Azab, M.M. Hybrid versus distance learning environment for a paediatric dentistry course and its influence on students’ satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).