Fundamental Movement Skills in Hong Kong Kindergartens: A Grade-Level Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Fundamental Movement Skill Development in Early Childhood Education

2.2. Hong Kong’s Curriculum Framework for Physical Activities and FMS Development

3. Research Goals

4. Method

4.1. Participants

4.2. Research Design and Data Collection Instrument

4.3. Procedure

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Results

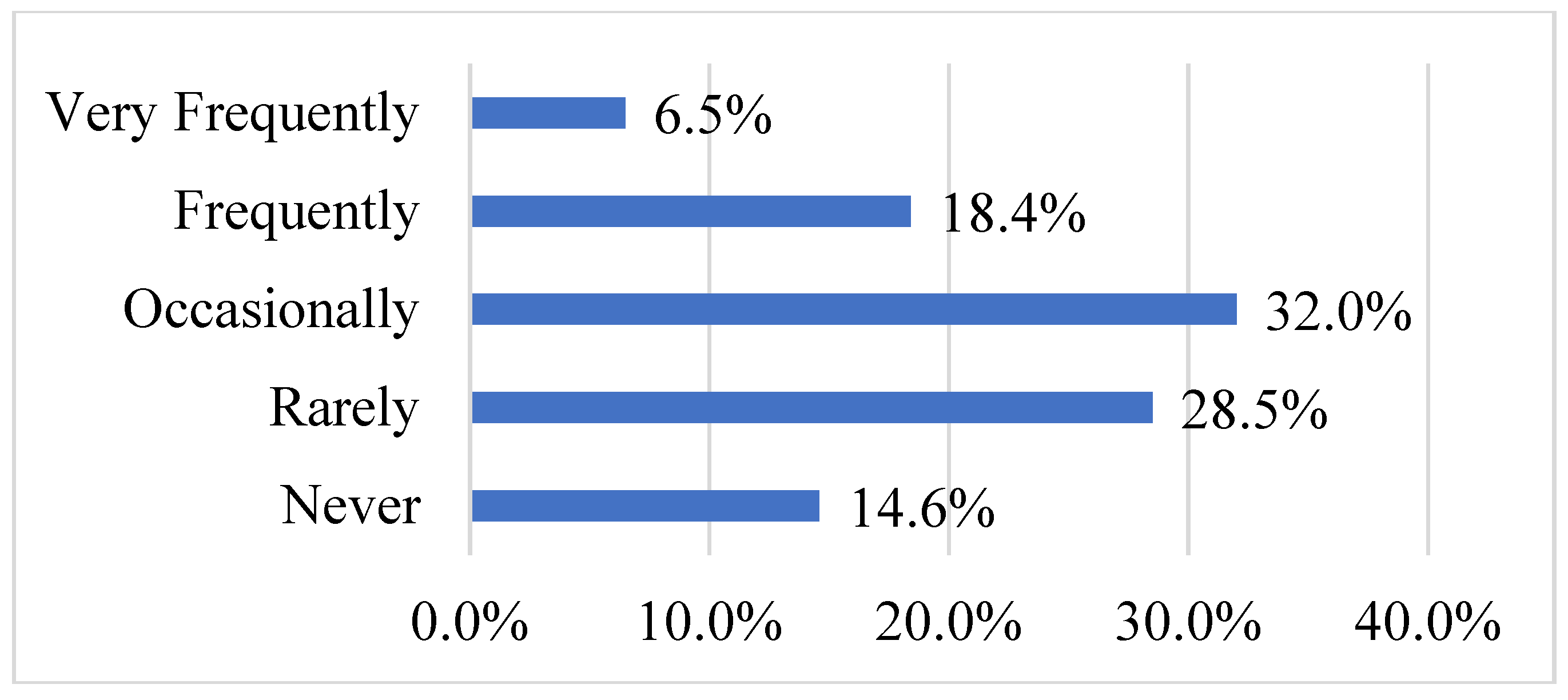

5.1. Goal #1: Fundamental Movement Skills Involved in Physical Activities

5.2. Goal #2: Association Among FMSs Based on the Frequency of Use in Classrooms

- Component 1: Springing

- Component 2: Interlimb Coordination

- Component 3: Object Manipulation

- Component 4: Even Locomotor Movements

- Component 5: Uneven Locomotor Movements

- Component 6: Agility and Coordination

- Component 7: Body Control

5.3. Goal #3: Grade Level Differences

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations and Future Research

9. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lubans, D.R.; Morgan, P.J.; Cliff, D.P.; Barnett, L.M.; Okely, A.D. Fundamental movement skills in children and adolescents. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 1019–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capio, C.M.; Sit, C.H.P.; Eguia, K.F.; Abernethy, B.; Masters, R.S.W. Fundamental movement skills training to promote physical activity in children with and without disability: A pilot study. J. Sport Health Sci. 2015, 4, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.G.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; O’Neill, J.R.; Dowda, M.; McIver, K.L.; Brown, W.H.; Pate, R.R. Motor skill performance and physical activity in preschool children. Obesity 2008, 16, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geertsen, S.S.; Thomas, R.; Larsen, M.N.; Dahn, I.M.; Andersen, J.N.; Krause-Jensen, M.; Korup, V.; Nielsen, C.M.; Wienecke, J.; Ritz, C.; et al. Motor skills and exercise capacity are associated with objective measures of cognitive functions and academic performance in preadolescent children. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, P.; Contreras, O.R.; Roblizo, M.-J.; Gómez, I. Educational potential of physical education in pre-school and infant education: Attributes and opinions. J. Study Educ. Dev. 2008, 31, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society of Health and Physical Educators. National Physical Education Standards. Available online: https://www.shapeamerica.org/standards/pe/default.aspx (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Western Sydney Local Health District. Fundamental Movement Skills. Available online: https://www.wslhd.health.nsw.gov.au/Healthy-Children/Our-Programs/Munch-Move/Fundamental-Movement-Skills (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Education Department of Western Australia. Fundamental Movement Skills: Book 1—Learning, Teaching and Assessment; Education Department of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 2013.

- Niederer, I.; Kriemler, S.; Gut, J.; Hartmann, T.; Schindler, C.; Barral, J.; Puder, J.J. Relationship of aerobic fitness and motor skills with memory and attention in preschoolers (Ballabeina): A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. BMC Pediatr. 2011, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, K.A.; Kendeigh, C.A.; Saelens, B.E.; Kalkwarf, H.J.; Sherman, S.N. Physical activity in child-care centers: Do teachers hold the key to the playground? Health Educ. Res. 2012, 27, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, L.M.; Van Beurden, E.; Morgan, P.J.; Brooks, L.O.; Beard, J.R. Childhood motor skill proficiency as a predictor of adolescent physical activity. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 44, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; McLachlan, C.; Mugridge, O.; McLaughlin, T.; Conlon, C.; Clarke, L. The effect of a 10-week physical activity programme on fundamental movement skills in 3–4-year-old children within early childhood education centres. Children 2021, 8, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Liang, W.-J.; Sun, F.-C. The impact of integrating musical and image technology upon the level of learning engagement of pre-school children. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinšek, M.; Denac, O. The effects of an integrated programme on developing fundamental movement skills and rhythmic abilities in early childhood. Early Child. Educ. J. 2020, 48, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos, H.C.; Gil Madrona, P.; Losada Puente, L.; Brian, A.; Saraiva, L. The relationship between early childhood teachers’ professional development in physical education and children’s fundamental movement skills. Early Educ. Dev. 2024, 35, 950–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, L.E.; Bolger, L.A.; O’Neill, C.; Coughlan, E.; O’Brien, W.; Lacey, S.; Burns, C.; Bardid, F. Global levels of fundamental motor skills in children: A systematic review. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 717–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClintic, S.; Petty, K. Exploring early childhood teachers’ beliefs and practices about preschool outdoor play: A qualitative study. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 2015, 36, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, J.; Leyton, B.; Soto-Sánchez, J.; Concha, F. In preschool children, physical activity during school time can significantly increase by intensifying locomotor activities during physical education classes. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, A.; Moreno-Núñez, A.; Vijayakumar, P.; Quek, E.; Bull, R. Gross motor teaching in preschool education: Where, what, and how do Singapore educators teach? Infanc. Aprendiz./J. Study Educ. Dev. 2020, 43, 443–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.H.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; McIver, K.L.; Dowda, M.; Addy, C.L.; Pate, R.R. Social and environmental factors associated with preschoolers’ nonsedentary physical activity. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howie, E.K.; Brown, W.H.; Dowda, M.; McIver, K.L.; Pate, R.R. Physical activity behaviours of highly active preschoolers. Pediatr. Obes. 2013, 8, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, Y.L.; Bautista, A. Music activities in Hong Kong kindergartens: A content analysis of the Quality Review reports. Rev. Electrónica LEEME, 2022; 32, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Lau, C.; Chan, S. Responsive Policymaking and Implementation: From Equality to Equity. A Case Study of the Hong Kong Early Childhood Education and Care System; Teachers College: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Li, H. The role of culture in early childhood curriculum development: A case study of curriculum innovations in Hong Kong kindergartens. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2022, 23, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curriculum Development Council. Kindergarten Education Curriculum Guide; Curriculum Development Council: Hong Kong, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, T.; Bautista, A.; Chan, D.K.C. Physical activities in Hong Kong kindergartens: A content analysis of the quality review reports. Policy Futures Educ. 2024, 22, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, W.K.G. Public Policy Research on “Investigating Space in Kindergartens under the Free Quality Kindergarten Education Scheme”. Available online: https://www.eduhk.hk/ielc/other/ppn/resources/impact/themes/whole-school-commitment/research%20brief/Investigating%20Space%20in%20Kindergartens.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Pate, R.R.; McIver, K.; Dowda, M.; Brown, W.H.; Addy, C. Directly observed physical activity levels in preschool children. J. Sch. Health 2008, 78, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, R.H.; Nobre, G.C.; Pessoa, M.L.F.; Soares, Í.A.A.; Bezerra, J.; Gaya, A.R.; Mota, J.A.P.S.; Duncan, M.J.; Martins, C.M.L. Physical activity during school-time and fundamental movement skills: A study among preschoolers with and without physical education classes. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2024, 29, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Bureau. Key Statistics on Kindergarten. Available online: https://www.edb.gov.hk/en/about-edb/publications-stat/figures/index.html (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Ian, J. Research Methods for Sports Studies, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Harrow, A.J. A Taxanomy of the Psychomotor Domain; David Mckay Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Seefeldt, V. Developmental motor patterns: Implications for elementary school physical fitness. In Psychology of Motor Behavior and Sport; Nadeau, C.H., Halliwell, W.R., Newell, K.M., Roberts, G.C., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1980; pp. 314–323. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, R.N.; Gerson, R.F. Task classification and strategy utilization in motor skills. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1981, 52, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, N.; Wyatt, S.; Jackman, H. Early Education Curriculum: A Child’s Connection to the World, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Education Department of Western Australia. Fundamental Movement Skills: Book 2—The Tools for Learning, Teaching and Assessment; Education Department of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 2013.

- Paris, J.; Beeve, K.; Springer, C. Introduction to Curriculum for Early Childhood Education; College of the Canyons: Santa Clarita, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I.T. Principal Component Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Beavers, A.S.; Lounsbury, J.W.; Richards, J.K.; Huck, S.W.; Skolits, G.J.; Esquivel, S.L. Practical considerations for using exploratory factor analysis in educational research. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2013, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, B.C.; Mckenzie, T.L.; Louie, L. Physical activity and its context during preschool classroom sessions. Adv. Phys. Educ. 2015, 5, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Montague, B. Move to learn, learn to move: Prioritizing physical activity in early childhood education programming. Early Child. Educ. J. 2016, 44, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, L.L.; King, L.; Farrell, L.; Macniven, R.; Howlett, S. Fundamental movement skills among Australian preschool children. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2010, 13, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.M.; Stodden, D.; Cohen, K.E.; Smith, J.J.; Lubans, D.R.; Lenoir, M.; Iivonen, S.; Miller, A.D.; Laukkanen, A.; Dudley, D.; et al. Fundamental movement skills: An important focus. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2016, 35, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Bautista, A.; Chan, D.K.C. Provision of Physical Activities in Hong Kong Kindergartens: Grade-Level Differences and Venue Utilization. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2024. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.E. Moving to the beat: Using music, rhythm, and movement to enhance self-regulation in early childhood classrooms. Int. J. Early Child. 2018, 50, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, P.; van Zandvoort, M.M.; Burke, S.M.; Irwin, J.D. Physical activity at daycare: Childcare providers’ perspectives for improvements. J. Early Child. Res. 2011, 9, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saamong, C.R.S.; Oropilla, C.T.; Chan, D.K.C.; Capio, C.M. Movement and physical activity experiences of early childhood teachers: Practices and contexts. J. Study Educ. Dev. in press.

- Martínez-Bello, V.E.; Bernabé-Villodre, M.D.M.; Lahuerta-Contell, S.; Vega-Perona, H.; Giménez-Calvo, M. Pedagogical knowledge of structured movement sessions in the early education curriculum: Perceptions of teachers and student teachers. Early Child. Educ. J. 2021, 49, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinsek, M.; Kovac, M. Beliefs of Slovenian early childhood educators regarding the implementation of physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyniuk, O.J.; Tucker, P. An exploration of early childhood education students’ knowledge and preparation to facilitate physical activity for preschoolers: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saamong, C.R.S.; Deogracias, P.K.E.; Saltmarsh, S.O.; Chan, D.K.C.; Capio, C.M. Early childhood teachers’ perceptions of physical activity: A scoping review. Early Child. Educ. J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capio, C.M.; Jones, R.A.; Ng, C.S.M.; Sit, C.H.P.; Chung, K.K.H. Movement guidelines for young children: Engaging stakeholders to design dissemination strategies in the Hong Kong early childhood education context. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saamong, C.R.S.; Oropilla, C.T.; Bautista, A.; Capio, C.M. A context-specific exploration of teacher agency in the promotion of movement and physical activities in early childhood education and care settings. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, J.; Bautista, A.; Siu, C.T.S.; Tam, P.C.; Wong, K.M. Arts and creativity in Hong Kong kindergartens: A document analysis of quality review reports. Creat. Theor. Res. Appl. 2022, 9, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. Educators’ Guide for Health, Safety and Motor Skills Development; Ministry of Education: Singapore, 2023.

| Characteristic | Frequency (n = 526) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 499 | 94.7% |

| Male | 22 | 4.2% |

| Unspecified | 5 | 1.0% |

| Kindergarten Level | ||

| K1 | 196 | 37.3% |

| K2 | 157 | 29.8% |

| K3 | 173 | 32.9% |

| Age | ||

| 20 or below | 4 | 0.8% |

| 20–29 | 342 | 65.0% |

| 30–39 | 102 | 19.4% |

| 40–49 | 49 | 9.3% |

| 50–59 | 27 | 5.1% |

| 60+ | 2 | 0.4% |

| Working Mode | ||

| Part time | 38 | 7.2% |

| Full time | 488 | 92.8% |

| Educational Qualification | ||

| Associate degree/higher diploma or lower | 338 | 64.3% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 138 | 26.2% |

| Postgraduate or above | 50 | 9.5% |

| Teaching Experience | ||

| 5 years or less | 312 | 59.3% |

| 5–15 years | 149 | 28.3% |

| 15+ years | 65 | 12.4% |

| Fundamental Movement Skill | Never (1) | Rarely (2) | Occasionally (3) | Frequently (4) | Very Frequently (5) | Overall Mean (SD) | 95% CI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | LB | UB | ||

| Riding on pedal tricycles or bikes | 20 | 3.8 | 52 | 9.9 | 117 | 22.2 | 178 | 33.8 | 159 | 30.2 | 3.77 (1.10) | 3.67 | 3.86 |

| Bending and stretching | 22 | 4.2 | 70 | 13.3 | 138 | 26.2 | 169 | 32.1 | 127 | 24.1 | 3.59 (1.12) | 3.49 | 3.68 |

| Walking or running on different levels | 31 | 5.9 | 92 | 17.5 | 156 | 30.2 | 110 | 20.9 | 134 | 25.5 | 3.43 (1.21) | 3.32 | 3.53 |

| Jumping vertically | 25 | 4.8 | 53 | 10.1 | 191 | 36.3 | 191 | 36.6 | 66 | 12.5 | 3.42 (0.99) | 3.33 | 3.50 |

| Tossing, throwing, and/or catching | 5 | 1.0 | 71 | 13.5 | 216 | 41.1 | 196 | 37.3 | 38 | 7.2 | 3.36 (0.84) | 3.29 | 3.43 |

| Dynamic balancing | 15 | 2.9 | 70 | 13.3 | 213 | 40.5 | 184 | 35.0 | 44 | 8.4 | 3.33 (0.91) | 3.25 | 3.40 |

| Walking or running on different pathways | 10 | 1.9 | 82 | 15.6 | 216 | 41.1 | 162 | 30.8 | 56 | 10.6 | 3.33 (0.93) | 3.25 | 3.41 |

| Ball bouncing/dribbling | 18 | 3.4 | 94 | 17.9 | 228 | 43.3 | 149 | 28.3 | 37 | 7.0 | 3.18 (0.92) | 3.10 | 3.26 |

| Crawling | 22 | 4.2 | 115 | 21.9 | 211 | 40.1 | 128 | 24.3 | 50 | 9.5 | 3.13 (1.00) | 2.05 | 3.22 |

| Kicking a ball | 16 | 3.0 | 124 | 23.6 | 240 | 45.6 | 120 | 22.8 | 26 | 4.9 | 3.03 (0.89) | 2.95 | 3.11 |

| Hopping | 42 | 8.0 | 93 | 17.7 | 222 | 42.2 | 150 | 28.5 | 19 | 3.6 | 3.02 (0.96) | 2.94 | 3.10 |

| Climbing | 94 | 17.9 | 106 | 20.2 | 140 | 26.6 | 119 | 22.6 | 67 | 12.7 | 2.92 (1.28) | 2.81 | 3.03 |

| Skipping | 49 | 9.3 | 153 | 29.1 | 210 | 39.9 | 89 | 16.9 | 25 | 4.8 | 2.79 (0.99) | 2.70 | 2.87 |

| Lifting and/or raising objects | 63 | 12.0 | 162 | 30.8 | 170 | 32.3 | 113 | 21.5 | 18 | 3.4 | 2.74 (1.04) | 2.65 | 2.82 |

| Pulling and/or pushing objects | 42 | 8.0 | 189 | 35.9 | 180 | 34.2 | 100 | 19.0 | 15 | 2.9 | 2.73 (0.95) | 2.65 | 2.81 |

| Static balancing | 72 | 13.7 | 163 | 31.0 | 185 | 35.2 | 84 | 16.0 | 22 | 4.2 | 2.66 (1.04) | 2.57 | 2.75 |

| Jumping horizontally | 55 | 10.5 | 184 | 35.0 | 211 | 40.1 | 67 | 12.7 | 9 | 1.7 | 2.60 (0.90) | 2.53 | 2.68 |

| Rolling a ball | 53 | 10.1 | 192 | 36.5 | 220 | 41.8 | 53 | 10.1 | 8 | 1.5 | 2.56 (0.86) | 2.49 | 2.64 |

| Leaping | 74 | 14.1 | 185 | 35.2 | 186 | 35.4 | 71 | 13.4 | 10 | 1.9 | 2.54 (0.96) | 2.46 | 2.62 |

| Walking on bucket stilts | 124 | 23.6 | 159 | 30.2 | 165 | 31.4 | 64 | 12.2 | 14 | 2.7 | 2.40 (1.06) | 2.31 | 2.49 |

| Balancing objects | 60 | 11.4 | 243 | 46.2 | 183 | 34.8 | 36 | 6.8 | 4 | 0.8 | 2.39 (0.81) | 2.32 | 2.46 |

| Jumping off a platform with a low height | 119 | 22.6 | 180 | 34.2 | 148 | 28.1 | 63 | 12.0 | 16 | 3.0 | 2.39 (1.05) | 2.30 | 2.48 |

| Dodging | 118 | 22.4 | 217 | 41.3 | 147 | 27.9 | 42 | 8.0 | 2 | 0.4 | 2.23 (0.90) | 2.15 | 2.30 |

| Galloping | 130 | 27.4 | 199 | 37.8 | 156 | 29.7 | 37 | 7.0 | 4 | 0.8 | 2.21 (0.92) | 2.13 | 2.29 |

| Rolling/tumbling | 131 | 24.9 | 215 | 40.9 | 146 | 27.8 | 33 | 6.3 | 1 | 0.2 | 2.16 (0.88) | 2.08 | 2.23 |

| Twisting | 141 | 26.8 | 204 | 38.8 | 144 | 27.4 | 30 | 5.7 | 7 | 1.3 | 2.16 (0.93) | 2.08 | 2.24 |

| Hitting a ball with hands or equipment | 154 | 29.3 | 198 | 37.6 | 143 | 27.2 | 27 | 5.1 | 4 | 0.8 | 2.10 (0.91) | 2.03 | 2.18 |

| Rope skipping | 208 | 39.5 | 186 | 35.4 | 105 | 20.0 | 22 | 4.2 | 5 | 1.0 | 1.92 (0.92) | 1.84 | 1.99 |

| Digging in sandbox | 311 | 59.1 | 139 | 26.4 | 53 | 10.1 | 15 | 2.9 | 8 | 1.5 | 1.61 (0.89) | 1.54 | 1.69 |

| OVERALL | 76.7 | 14.6 | 144.5 | 28.5 | 173.8 | 32.0 | 96.6 | 18.4 | 41.2 | 6.5 | 2.62 (0.44) | 2.58 | 2.65 |

| Fundamental Movement Skill | Component | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Jumping vertically | 0.595 | ||||||

| Bending and stretching | 0.578 | ||||||

| Hopping | 0.517 | ||||||

| Dynamic balancing | 0.430 | ||||||

| Riding on pedal tricycles or bikes | 0.611 | ||||||

| Climbing | 0.565 | ||||||

| Static balancing | 0.468 | ||||||

| Crawling | 0.453 | ||||||

| Kicking a ball | 0.707 | ||||||

| Ball bouncing/dribbling | 0.700 | ||||||

| Tossing, throwing, and/or catching | 0.639 | ||||||

| Pulling and/or pushing objects | 0.573 | ||||||

| Lifting and/or raising objects | 0.566 | ||||||

| Balancing objects | 0.440 | ||||||

| Jumping off a platform with a low height | 0.691 | ||||||

| Jumping horizontally | 0.592 | ||||||

| Walking or running on different levels | 0.570 | ||||||

| Skipping | 0.757 | ||||||

| Galloping | 0.757 | ||||||

| Leaping | 0.700 | ||||||

| Rope skipping | 0.708 | ||||||

| Walking on bucket stilts | 0.688 | ||||||

| Dodging | 0.430 | ||||||

| Rolling/tumbling | 0.711 | ||||||

| Twisting | 0.649 | ||||||

| Rolling a ball | 0.458 | ||||||

| Hitting a ball with hands or equipment | 0.488 | ||||||

| Digging in sandbox | 0.444 | ||||||

| Fundamental Movement Skill | Overall Mean (SD) | K1 | K2 | K3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | M (SD) | Rank | M (SD) | Rank | M (SD) | ||

| Riding on pedal tricycles or bikes | 3.77 (1.10) | 1st | 3.79 (1.16) | 1st | 3.66 (1.08) | 1st | 3.84 (1.04) |

| Bending and stretching d | 3.59 (1.12) | 6th | 3.38 * (1.12) | 2nd | 3.60 (1.18) | 2nd | 3.82 (1.01) |

| Walking or running on different levels | 3.43 (1.21) | 2nd | 3.52 (1.16) | 3rd | 3.36 (1.22) | 5th | 3.38 (1.25) |

| Jumping vertically e | 3.42 (0.99) | 3rd | 3.43 (1.04) | 7th | 3.26 *** (1.00) | 3rd | 3.55 (0.91) |

| Tossing, throwing, and/or catching | 3.36 (0.84) | 8th | 3.31 (0.86) | 4th | 3.33 (0.85) | 4th | 3.46 (0.80) |

| Dynamic balancing | 3.33 (0.91) | 7th | 3.35 (0.92) | 5th | 3.28 (0.95) | 7th | 3.35 (0.85) |

| Walking or running on different pathways | 3.33 (0.93) | 5th | 3.41 (0.98) | 6th | 3.27 (0.88) | 9th | 3.28 (0.91) |

| Ball bouncing/dribbling f | 3.18 (0.92) | 9th | 3.05 *** (0.98) | 8th | 3.11 *** (0.90) | 5th | 3.38 (0.85) |

| Crawling a | 3.13 (1.00) | 4th | 3.42 (0.92) | 10th | 2.96 * (0.86) | 12th | 2.96 * (1.12) |

| Kicking a ball e | 3.03 (0.89) | 10th | 3.02 (0.93) | 12th | 2.86 *** (0.87) | 10th | 3.20 (0.83) |

| Hopping c | 3.02 (0.96) | 14th | 2.72 * (1.02) | 9th | 3.10 (0.84) | 8th | 3.29 (0.91) |

| Climbing | 2.92 (1.28) | 11th | 2.81 (1.30) | 11th | 2.90 (1.32) | 11th | 3.07 (1.23) |

| Skipping | 2.79 (0.99) | 15th | 2.70 (1.06) | 13th | 2.77 (0.99) | 14th | 2.90 (0.90) |

| Lifting and/or raising objects | 2.74 (1.03) | 12th | 2.77 (1.08) | 15th | 2.61 (1.02) | 15th | 2.82 (0.99) |

| Pulling and/or pushing objects | 2.73 (0.95) | 13th | 2.74 (0.89) | 14th | 2.64 (1.01) | 16th | 2.79 (0.97) |

| Static balancing | 2.66 (1.03) | 16th | 2.61 (1.06) | 16th | 2.58 (1.03) | 16th | 2.79 (1.01) |

| Jumping horizontally | 2.60 (0.90) | 18th | 2.56 (0.96) | 17th | 2.54 (0.84) | 18th | 2.71 (0.88) |

| Rolling a ball | 2.57 (0.86) | 17th | 2.59 (0.90) | 18th | 2.50 (0.83) | 20th | 2.59 (0.84) |

| Leaping | 2.54 (0.96) | 19th | 2.52 (1.04) | 19th | 2.45 (0.96) | 19th | 2.65 (0.84) |

| Walking on bucket stilts f | 2.40 (1.06) | 26th | 2.03 * (1.05) | 22nd | 2.30 * (1.00) | 13th | 2.91 (0.91) |

| Balancing objects d | 2.39 (0.81) | 21st | 2.29 *** (0.84) | 20th | 2.36 (0.74) | 21st | 2.54 (0.82) |

| Jumping off a platform with a low height | 2.39 (1.05) | 20th | 2.42 (1.09) | 20th | 2.36 (1.06) | 24th | 2.37 (1.02) |

| Dodging f | 2.23 (0.90) | 23rd | 2.11 * (0.94) | 26th | 2.08 * (0.78) | 22nd | 2.49 (0.91) |

| Galloping f | 2.21 (0.92) | 26th | 2.03 * (0.98) | 23rd | 2.17 *** (0.84) | 23rd | 2.46 (0.87) |

| Rolling/tumbling | 2.16 (0.88) | 22nd | 2.22 (0.92) | 27th | 2.06 (0.84) | 27th | 2.17 (0.86) |

| Twisting | 2.16 (0.93) | 24th | 2.07 (0.96) | 24th | 2.14 (0.90) | 26th | 2.28 (0.91) |

| Hitting a ball with hands or equipment | 2.11 (0.91) | 25th | 2.06 (0.97) | 25th | 2.11 (0.87) | 28th | 2.16 (0.88) |

| Rope skipping f | 1.92 (0.92) | 29th | 1.69 * (0.92) | 28th | 1.71 * (0.74) | 25th | 2.36 (0.91) |

| Digging in sandbox b | 1.61 (0.89) | 28th | 1.73 (1.01) | 29th | 1.50 *** (0.83) | 29th | 1.58 (0.79) |

| OVERALL | 2.62 (0.44) | 2.55 * (0.47) | 2.55 * (0.40) | 2.75 (0.42) | |||

| Component | F (2, 523) | K1 | K2 | K3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | M (SD) | Rank | M (SD) | Rank | M (SD) | ||

| Springing a | 8.821 | 1st | 3.22 * (0.72) | 1st | 3.31 *** (0.63) | 1st | 3.50 (0.59) |

| Interlimb Coordination | 1.945 | 2nd | 3.16 (0.74) | 2nd | 3.02 (0.69) | 2nd | 3.16 (0.76) |

| Object Manipulation a | 5.162 | 3rd | 2.86 *** (0.66) | 3rd | 2.82 *** (0.64) | 3rd | 3.03 (0.61) |

| Even Locomotor Movements | 0.476 | 4th | 2.84 (0.82) | 4th | 2.75 (0.78) | 4th | 2.82 (0.80) |

| Uneven Locomotor Movements a | 5.422 | 5th | 2.42 *** (0.84) | 5th | 2.46 *** (0.74) | 5th | 2.67 (0.71) |

| Agility and Coordination a | 48.299 | 7th | 1.95 * (0.74) | 7th | 2.03 * (0.59) | 6th | 2.59 (0.64) |

| Body Control | 1.054 | 6th | 2.13 (0.64) | 6th | 2.06 (0.56) | 7th | 2.15 (0.58) |

| OVERALL a | 2.65 * (0.54) | 2.63 * (0.46) | 2.85 (0.48) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, T.; Bautista, A.; Chan, D.K.C. Fundamental Movement Skills in Hong Kong Kindergartens: A Grade-Level Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080911

Fan T, Bautista A, Chan DKC. Fundamental Movement Skills in Hong Kong Kindergartens: A Grade-Level Analysis. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(8):911. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080911

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Thomas, Alfredo Bautista, and Derwin K. C. Chan. 2024. "Fundamental Movement Skills in Hong Kong Kindergartens: A Grade-Level Analysis" Education Sciences 14, no. 8: 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080911

APA StyleFan, T., Bautista, A., & Chan, D. K. C. (2024). Fundamental Movement Skills in Hong Kong Kindergartens: A Grade-Level Analysis. Education Sciences, 14(8), 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080911