Content and Languages Integration: Pre-Service Teachers’ Culturally Sustaining Social Studies Units for Emergent Bilinguals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How do pre-service teachers in an urban multicultural teacher education program integrate asset-based and strength-based ideologies into their social studies unit plans?

- How do pre-service teachers integrate bilingual/multilingual pedagogies into the social studies curriculum to support diverse learners’ needs and enhance subject-specific literacy?

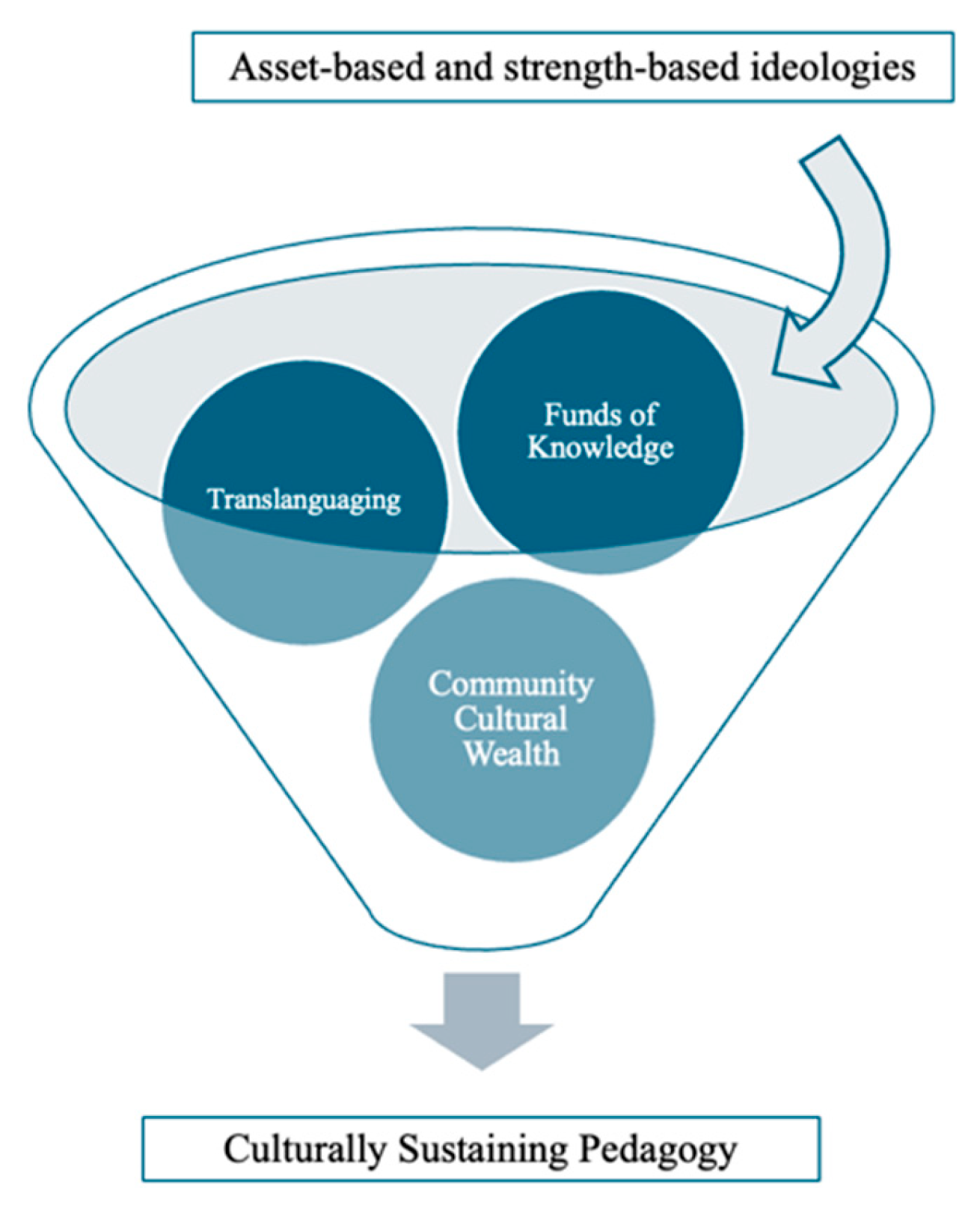

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Normalizing Translanguaging Practices in Social Studies Classrooms

4. Methodology

4.1. Context

4.2. Data Sources and Data Collection

4.3. Data Analysis

4.4. Positionality

5. Findings

- (1)

- Rooted in the community: Embodying locally relevant pedagogy

- From the beginning of my lesson, I begin to introduce the story of Sylvia Mendez and her fight for equality in schools. I tell students that this case was especially important for them because they attend California schools. Most of my students also come from Hispanic backgrounds, which this story/case focuses on, allowing students to learn how someone like them was able to make a big change. I ask questions of my students to activate and access their funds of knowledge and experiences on this topic. We then move on to the lesson, where we have a read aloud of Separate Is Never Equal [35] that shows what happened to Sylvia and her family, and how they overcame it to bring a change to the school system in California. The book provides images that portray students in my class and in the language that they hear and speak with. In the end, the whole class helps create a timeline of the events that took place in Sylvia’s fight for equality, ending it with primary video sources that show Sylvia talking about her experience and Sylvia receiving the presidential medal of freedom from President Barack Obama. This allows students to see and learn from the real person we are learning about.

- (2)

- Leveraging Linguistic Diversity: Centering Translanguaging and Multilingualism

- The read-aloud will use book, Fire! Fuego! Brave Bomberos by Susan Middleton Elya as a whole class. This book embraces the Spanish language, in which many of the students in the classroom are emergent bilinguals and speak Spanish at home. Students can include their primary language as they develop the English language. It promotes culturally responsive pedagogy by using students’ language as an asset in connecting to their experiences and knowledge. It also includes images that are more inclusive, such as of skin color and gender. Also, to bring in culturally diverse perspectives and culturally responsive pedagogy, the teacher will also ensure having at least two firefighters from different cultures within their local community (students’ family members who are firefighters) as guest speakers. They can share their experience in both English and Spanish. […] Moreover, students get to reflect on their own experiences with firefighters as they listen to the firefighters speak to better comprehend how they have helped and continue to help people in their neighborhoods.

- (3)

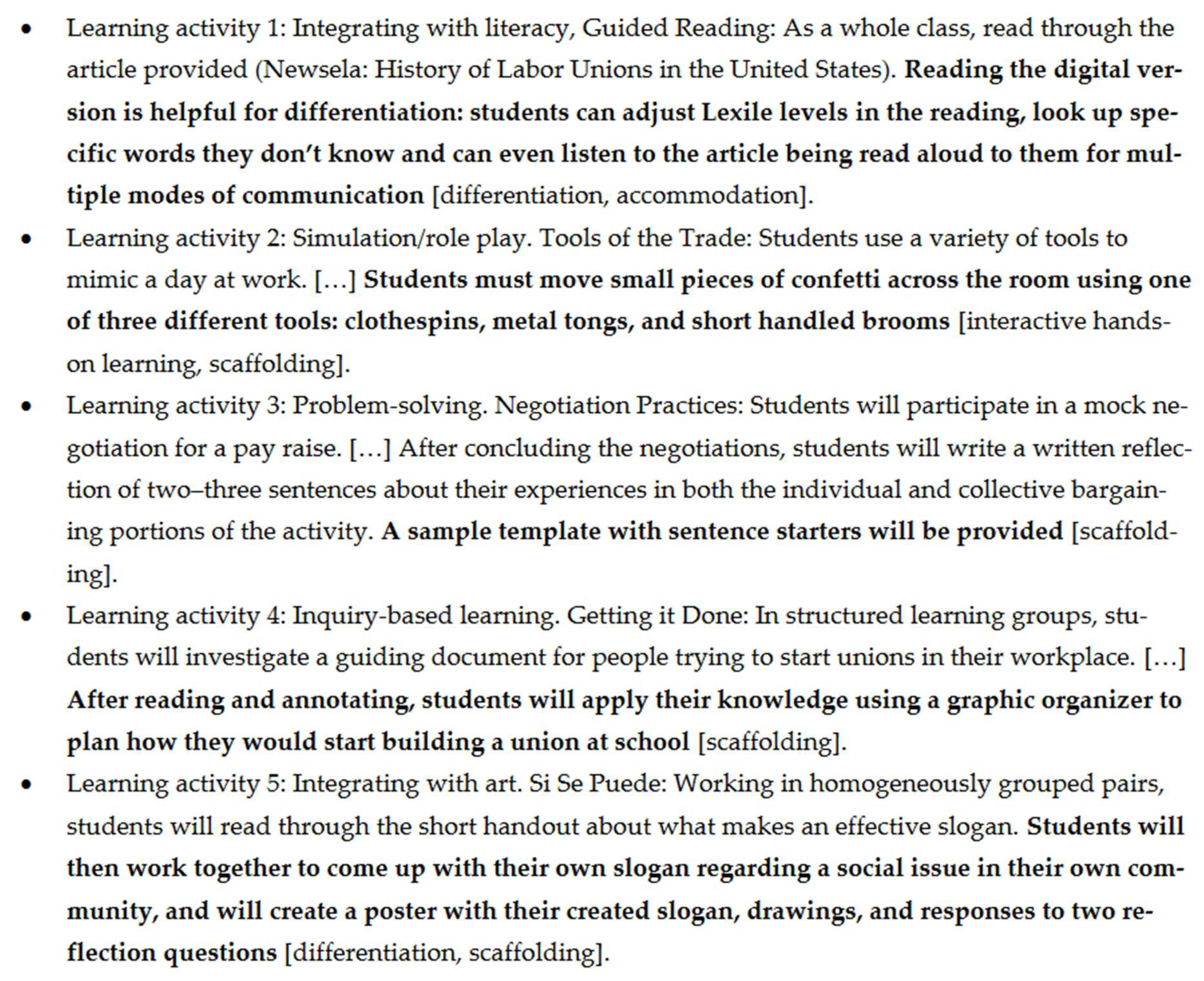

- Supporting and empowering learners through inclusive pedagogies

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Unit Plan Assignment

| Unacceptable | Approaching Novice | Novice | Proficient | Advanced | |

| Points | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 |

| Introduction | Introductory elements are missing or do not stem from the H-SS standards listed in Part 2. | Introductory elements stem from the H-SS standards listed in Part 2, but there is a lack of clarity or coherence among them. Includes real life applications. | Introductory elements are clear and coherent. Inquiry Question calls for an evidence-based explanation or opinion. | Inquiry and Supporting Questions are meaningful, and provide a foundation for use of analysis skills. | Rationale is strong and Inquiry Question is compelling. |

| Cultural Diversity and Culturally Responsive Teaching–(TPE 1.1) | Unit plan does not incorporate culturally diverse perspectives or embody culturally responsive pedagogy. | More than one cultural group is represented in the unit. or An activity makes reference to students’ experiential backgrounds. | Diverse cultural groups are represented in the unit. or More than one activity makes reference to students’ experiential backgrounds. | Culturally diverse perspectives are incorporated in the unit. or activities draw on students’ cultural backgrounds so as to enhance learning. | Culturally diverse perspectives are incorporated in the unit. and Activities draw on students’ cultural backgrounds so as to enhance learning. |

| Pedagogy—(TPE 3.3) Inquiry-Based Instruction—(TPE 1.5) | Instruction not consistent with current pedagogy as aligned to California Subject Matter Frameworks (CSMF) or uses inquiry | Instruction uses some inquiry and is somewhat consistent with current pedagogy as aligned to CSMF. | Instruction including Inquiry is consistent with current pedagogy as aligned to CSMF. | Instruction and Inquiry reflects expertise with pedagogy in either history-social science of English language arts and literacy. | Instruction and Inquiry reflects expertise with pedagogy in both history-social science and English language arts and literacy. |

| H-SS Disciplines Concepts and Themes—(TPE 3.1 and 3.3) | Instruction does not develop students’ understanding of key history-social science disciplines or concepts. Instruction does not incorporate big ideas, concepts, or themes. | Develops students’ understanding in 1 area:

| Instruction develops students’ understanding in at least 2 of the disciplinary areas. Instruction is centered around big ideas, concepts, and themes. | Instruction in any disciplinary area is well integrated with the central theme of the unit. Provides insights into historical events and cultures. | Instruction develops deep understanding in at least 2 of the disciplinary areas Big ideas, concepts, and themes are well-integrated throughout the unit plan. |

| Integrating Instruction—(TPE1.7 and 3.3 ELA Subject-Specific 1) Technology (and possibly 8) (TPE 4.8) | CCSS ELA or VAPA standards are missing. Instruction does not include use of digital tools or learning technologies | CCSS ELA and VAPA standards are listed, but a description of how they will be addressed is missing. Instruction includes use of digital tools or learning technologies. | A description of how ELA and VAPA standards will be addressed is included. Technology is not a replacement for traditional paper and pencil technology, but rather improves opportunities for learning | ELA standards include oral communication and vocabulary, reading comprehension and writing. VAPA is integrated within the unit to facilitate access to social studies content. | ELA and VAPA are integrated within the unit to enhance social studies, the arts, and literacy skills. Technology provides personalized and integrated tecnology-rich lessons, and offers students multiple means to demonstrate their learning. |

| Oral Communication and Vocabulary (TPE 3.3 and 3.4) | Instruction does not provide opportunities for students to develop oral communication nor does it include strategies to make language comprehensible to students. | Instruction provides opportunities for students to develop oral communication OR includes strategies to make language (vocabulary, conventions, or knowledge of language) comprehensible to students. | Instruction provides opportunities for students to develop oral communication and includes strategies to make language (vocabulary, conventions, and knowledge of language) comprehensible to students. | Instruction encourages students’ use of language to extend across reading, writing, speaking, and listening. | Instruction provides structured opportunities for language practice, and feedback for students to develop further language proficiency. |

| Comprehension Scaffolds—(TPE 3.3 and 3.4) | Instruction does not include strategies that support students’reading andcomprehension of subject-relevant narrative or informational texts. | Instruction includes strategies that support students’ reading and comprehension of subject-relevant narrative or informational texts. | Instruction includes strategies that support students’ reading comprehension of subject-relevant narrative and informational texts. | Instruction includes strategies that support students’ abilities to cite specific evidence in oral or written interpretation of text. | Instruction includes strategies that support students’ reading and comprehension of text structures and graphic/media representations in diverse formats/genres. |

| Writing Scaffolds-Inquiry Task (TPE 3.3 and 3.4) | Inquiry Task does not incorporate strategies to develop written literacy. | Inquiry Task incorporates written literacy teaching strategies, but these are not described in sufficient detail to determine whether they will support students in writing opinion/persuasive or expository texts. | Incorporates teaching strategies to support students in writing opinion/persuasive or expository texts in which students make claims or form interpretations based on primary and secondary documents. | Inquiry Task incorporates several strategies to support students in writing opinion/persuasive or expository texts, selected according to the written literacy demands of the Inquiry Task. | Teaching strategies are differentiated, to meet the needs of diverse learners. |

| Assessment (TPE 4.3 and 5.1) | Unit does not include assessment plan. | Unit includes an assessment plan, but students have not had sufficient opportunity to learn what is being assessed. | Includes an appropriate summative assessment with a scoring rubric, measuring either social studies or writing skills. | Includes appropriate formative and summative assessments, with rubric measuring both social studies and writing skills. | The scoring rubric provides in-depth information about students’ ability to produce an evidence-based opinion or explanation in writing. |

| Bibliography | Unit plan does not include a bibliography | Unit plan includes a bibliography, but citations are not complete. | Bibliography includes complete citations and brief annotation for each source. | Bibliography includes a variety of sources. | Bibliography includes a variety of sources representing diverse perspectives. |

Appendix B. Coding Scheme Examples

| Code | Definition | Examples |

| translanguaging | The practice of using multiple languages in instruction to support learning. | Bilingual instructions, mixing languages in teaching, students using home language. |

| funds of knowledge | Knowledge students bring from their home and community environments. | Family traditions, community practices, personal experiences related to the curriculum. |

| culturally relevant pedagogy | Teaching practices that recognize and incorporate students’ cultural backgrounds. | Culturally relevant examples in lesson plans, activities celebrating cultural diversity. |

| culturally sustaining pedagogy | Extending CRP by not only recognizing and incorporating students’ cultural backgrounds but also sustaining and fostering cultural pluralism in schools. | Examples sustaining and nurturing students’ cultural and linguistic identities, centering exploration of cultural and linguistic diversity. |

| scaffolding | Support provided to students to help them achieve learning goals. | Step-by-step instructions, guided practice, use of visuals and aids, including templates, tables, and modeling |

| differentiation | Tailoring instruction to meet individual needs. | Varied reading materials, different levels of difficulty in tasks, personalized assignments for emergent bilinguals |

| accommodation | Adjustments made to instruction or assessment to support diverse learners. | Extended time on tests, alternative assessment methods, assistive technology. |

| locally relevant pedagogy | Instruction that incorporates the cultural and historical aspects of local communities. | Lessons on local history, inclusion of local cultural practices in the curriculum. |

References

- National Center for Education Statistics. English Learners in Public Schools. In Condition of Education; U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences: New York, NY, USA, 2023. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgf (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- California Department of Education. Facts about English Learners in California. 2023. Available online: https://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/ad/cefelfacts.asp (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- García, O.; Kleifgen, J.; Falchi, L. From English language learners to emergent bilinguals. In Research Review Series Monograph, Campaign for Educational Equity; Teachers College, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- García, O.; Kleifgen, J. Educating Emergent Bilinguals: Policies, Programs, and Practices for English Language Learners; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, N.; Rosa, J.D. Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2015, 85, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, J.; Flores, N. Decolonization, language, and race in applied linguistics and social justice. Appl. Linguist. 2021, 42, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, S.J.; Son, M.; Ly-Hoang, K.; Zambrano, L. “Culture is where I come from”: An analysis of cultural competence of student teachers of color in early childhood education. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 2024, 45, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, B. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas, A.M.; Lucas, T. Preparing culturally responsive teachers: Rethinking the curriculum. J. Teach. Educ. 2002, 53, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanases, S.Z.; Banes, L.C.; Wong, J.W.; Martinez, D.C. Exploring linguistic diversity from the inside out: Implications of self-reflexive inquiry for teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 70, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, T.; Villegas, A.M.; Freedson-Gonzalez, M. Linguistically responsive teacher education: Preparing classroom teachers to teach English language learners. J. Teach. Educ. 2008, 59, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, R. Teachers of Color: Resisting Racism and Reclaiming Education; Harvard Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, G. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. What we can learn from multicultural education research. Educ. Leadersh. 1994, 51, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, D.; Alim, H.S. (Eds.) Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moll, L.C.; Amanti, C.; Neff, D.; Gonzalez, N. Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative Approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms. Theory Into Pract. 1992, 31, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosso, T.J. Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethn. Educ. 2005, 8, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O. Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Son, M.; Kim, E.H. Who Are Bilinguals? Surfacing Teacher Candidates’ Conceptions of Bilingualism. Languages. 2024, 9, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaire, F.; Pohl, B.; Miller, D.M. Children’s Literature as a vehicle for fostering elementary pre-service teachers’ science and social studies engagement. J. World Fed. Assoc. Teach. Educ. 2020, 3, 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Park, J.Y. Critical awareness toward Content-Language Integrated Education for Multilingual Learners (CA-CIEML): A survey study about teachers’ ideological beliefs and attitudes. Lang. Aware. 2024, 33, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J. Language ideologies and the education of speakers of marginalized language varieties: Adopting a critical awareness approach. Linguist. Educ. 2006, 17, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhang-Wu, Q. Preparing pre-service content area teachers through translanguaging. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 2022, 21, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, P.C.; Salinas, C. Reimagining language space with bilingual youth in a social studies classroom. Biling. Res. J. 2021, 44, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaňa, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Sun, W.; Son, M. The Voices of Transnational MotherScholars of Emergent Bilinguals. J. Lit. Res. 2024, 56, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Jang, S.B.; Jung, J.K.; Son, M.; Lee, S.Y. Negotiating Asian American identities: Collaborative self-study of Korean immigrant scholars’ reading group on AsianCrit. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.M.; Son, M.; Sun, W.; Ee, J.J.; Harris, S.; Kwon, J.; Lê, K.; Tian, Z. (Re)negotiating Asian and Asian American identities in solidarity as language teacher educators: An AsianCrit discourse analysis. TESOL J. 2024, e854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campano, G.; Ghiso, M.P.; Welch, B.J. Partnering with Immigrant Communities: Action through Literacy; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tonatiuh, D. Separate is Never Equal; Abrams Books for Young Readers: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, S.E. Dolores Huerta: A Hero to Migrant Workers; Marshall Cavendish Children: Singapore, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’dell, S. Island of the Blue Dolphins; Penguin: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Alvitre, C.; Lake, C. Waa’aka’: The Bird who Fell in Love with the Sun; Heyday: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dorros, A. Abuela (English Edition with Spanish Phrases); Puffin Books: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ada, A.F.; Savadier, E. I Love Saturdays y Domingos; Atheneum Books for Young Readers: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Son, M. Content and Languages Integration: Pre-Service Teachers’ Culturally Sustaining Social Studies Units for Emergent Bilinguals. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080915

Son M. Content and Languages Integration: Pre-Service Teachers’ Culturally Sustaining Social Studies Units for Emergent Bilinguals. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(8):915. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080915

Chicago/Turabian StyleSon, Minhye. 2024. "Content and Languages Integration: Pre-Service Teachers’ Culturally Sustaining Social Studies Units for Emergent Bilinguals" Education Sciences 14, no. 8: 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080915

APA StyleSon, M. (2024). Content and Languages Integration: Pre-Service Teachers’ Culturally Sustaining Social Studies Units for Emergent Bilinguals. Education Sciences, 14(8), 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080915