A Justice-Oriented Conceptual and Analytical Framework for Decolonising and Desecularising the Field of Educational Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Terminology

- Educational Technology (EdTech): This encompasses the hardware, software, products, services, infrastructure, applications, and interfaces [6].

- The field of EdTech: This refers more broadly to the projects, programmes, processes, policies, strategies, values, knowledge systems, and philosophies that EdTech are situated in [6].

- Global North and Global South: These terms are used to acknowledge the colonial and neocolonial influences of some regions over others and are, thus, geopolitical rather than geographic. These are used instead of economic groupings like “low-income countries” since the latter does not acknowledge the power dynamics in play, or the geopolitical injustices that led to some countries being wealthier than others. Occasionally, Western and Euro-American are used if the cited scholars use these terms or if epistemic roots of knowledge are being discussed. All these terms are used acknowledging they refer to the dominant modern systems of thought from those regions, and not the marginalised schools of thought (such as those from the indigenous groups in the Americas).

- Coloniality: This refers to the “long-standing patterns of power that emerged as a result of colonialism, but that define culture, labour, intersubjectivity relations, and knowledge production well beyond the strict limits of colonial administrations. Thus, coloniality survives colonialism. It is maintained alive in books, in the criteria for academic performance, in cultural patterns, in common sense, in the self-image of peoples, in aspirations of self, and so many other aspects of our modern experience” [7] (p. 243).

- Decoloniality: This refers to “the dismantling of relations of power and conceptions of knowledge that foment the reproduction of racial, gender, and geopolitical hierarchies that came into being or found new and more powerful forms of expression in the modern/colonial world” [8] (p. 440).

- Technological way of being: This phrase is used at two levels. At a practical level, this phrase refers to how technology has permeated throughout our lives, shaping, for example, how we think, behave, communicate, socialise, learn, and work. This guides our values, behaviours, and experiences of and in the world. At a philosophical level, it is used in the Heideggerian sense to refer to a technological mindset that views the world (and human beings) instrumentally as resources to be utilised, optimised, and dominated, leading to exploitative engagements with the world [5]. Furthermore, this focus on productivity and efficiency leads to the forgetfulness of our intrinsic purpose and the questions of existence.

2.2. Developing a Conceptual Framework

2.3. Origins of the Research and Positionality

2.4. Theoretical Framing

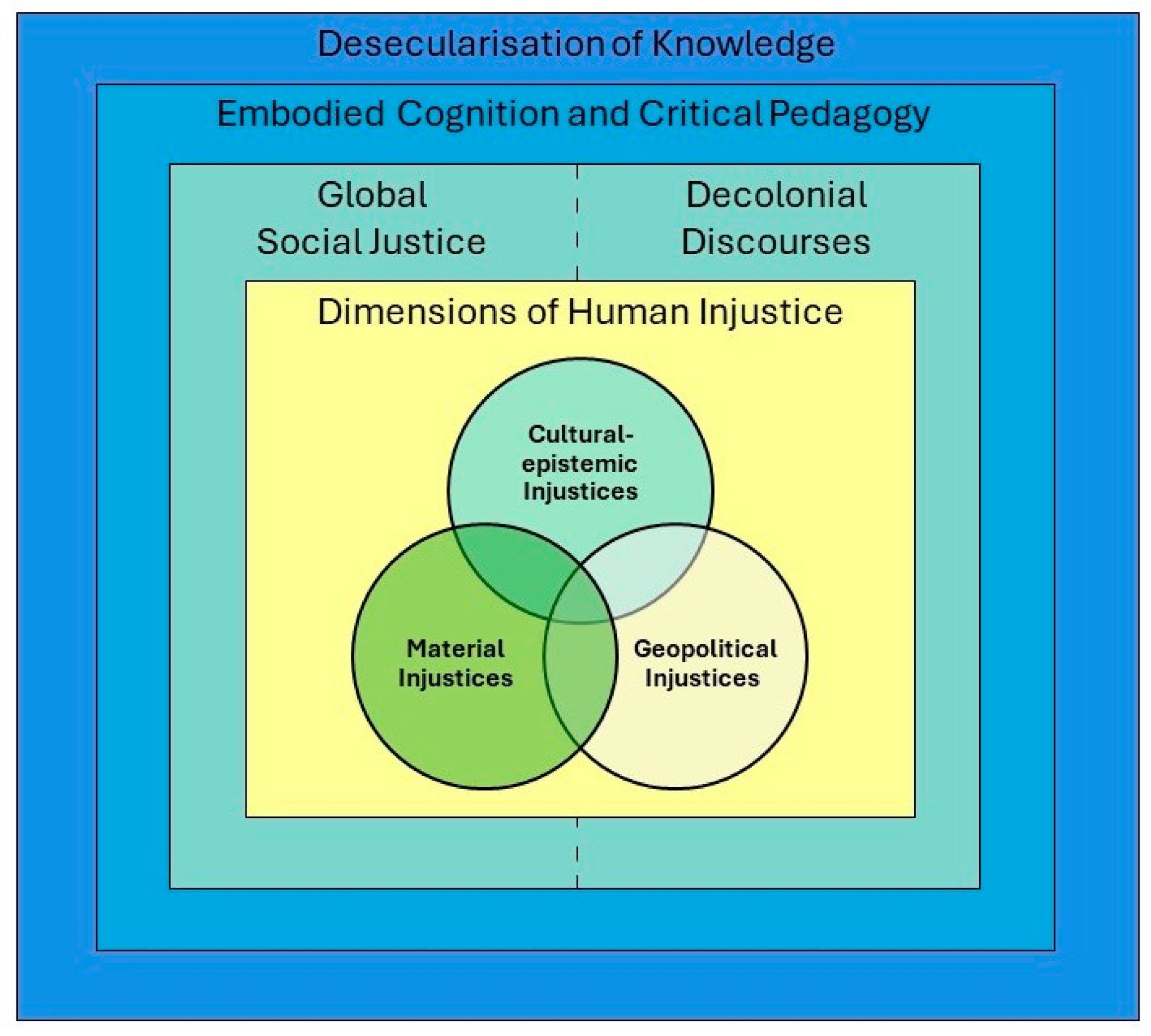

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1. Desecularisation of Knowledge

3.1.1. The Nature of Knowledge

3.1.2. The Purpose of Education

3.1.3. The Meaning of Justice

3.2. Embodied Cognition and Critical Pedagogy

3.2.1. Embodied Cognition

3.2.2. Embodiment and Critical Reflexivity

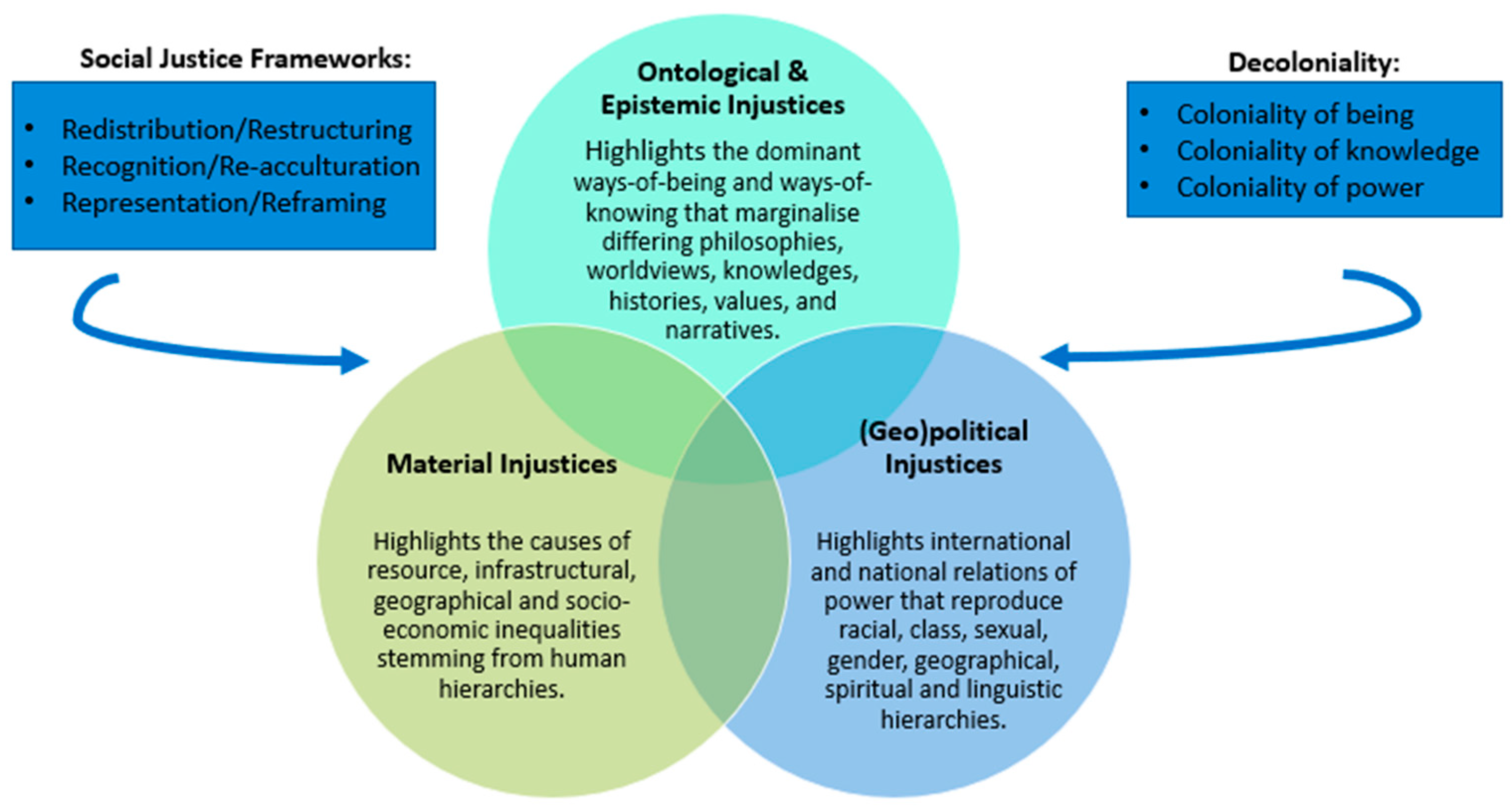

3.3. Social Justice

3.3.1. Dominant Global North Theories of Justice

3.3.2. Global Social Justice

3.3.3. Social Justice in Global South Education

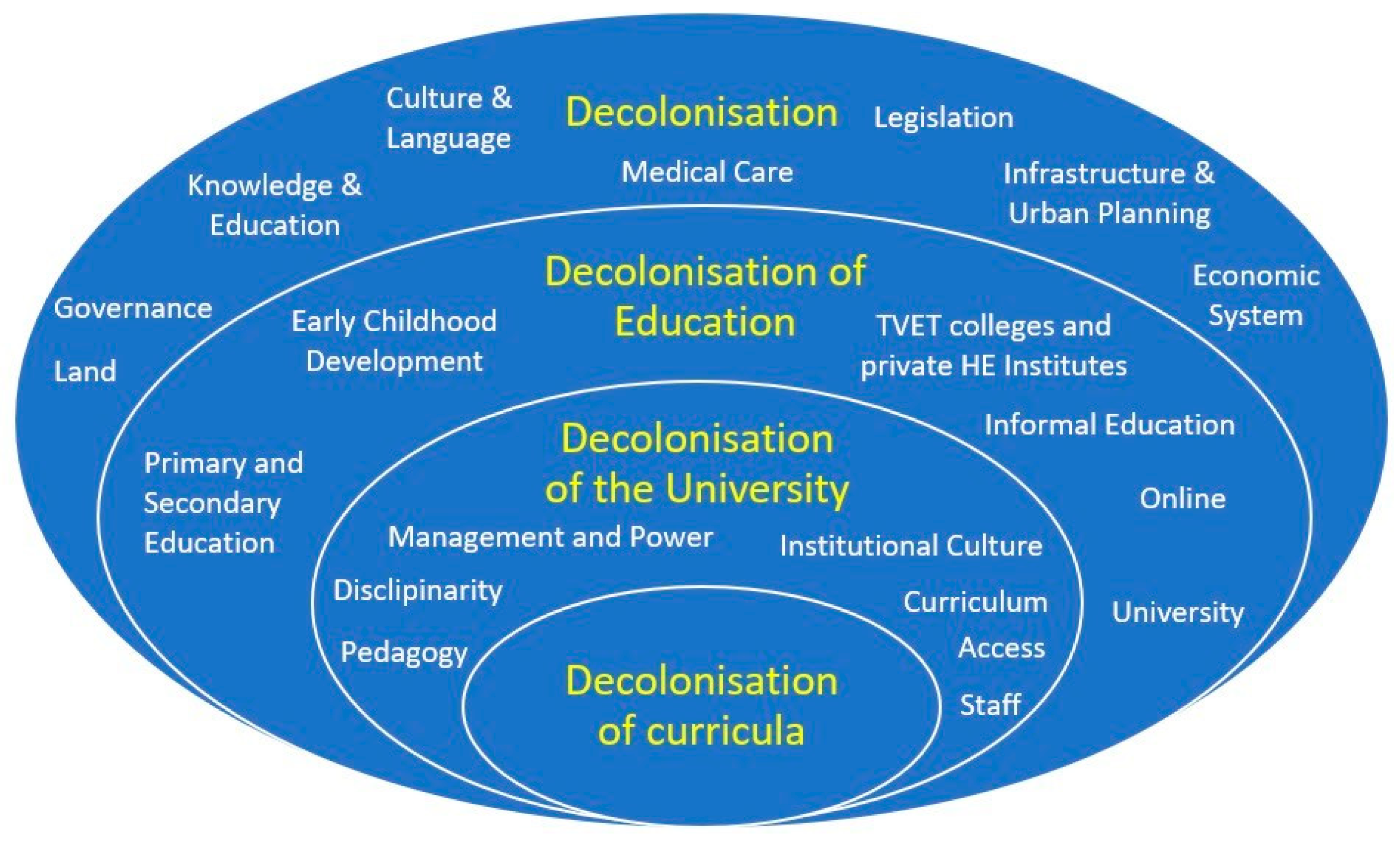

3.4. Decoloniality

3.4.1. Overview of Decolonial Thought

3.4.2. Decolonising Education

3.4.3. Decolonising Technology and Development

4. Analytical Framework for Decolonising Educational Technology

4.1. Material Injustices in EdTech

4.2. Ontological and Epistemic Injustices in EdTech

4.3. Geopolitical Injustices in EdTech

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNICEF. Pulse Check on Digital Learning; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, W.; Miao, F. Guidance for Generative AI in Education and Research; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, T.; Moustafa, N.; Sarwar, M. Tackling Coloniality in EdTech: Making Your Offering Inclusive and Socially Just; EdTech Hub: Virtual, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, T. Digital Neocolonialism and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs): Colonial Pasts and Neoliberal Futures. Learn. Media Technol. 2019, 44, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, M. The Question Concerning Technology; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Koole, M.; Smith, M.; Traxler, J.; Adam, T.; Footring, S. Decolonising Educational Technology. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/si/128574 (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Maldonado-Torres, N. On the Coloniality of Being. Cult. Stud. 2007, 21, 240–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Torres, N. Césaire’s Gift and the Decolonial Turn. In Critical Ethnic Studies; Duke University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, R.; Iniesto, F.; Weller, M.; Pitt, R.; Algers, A.; Bozkurt, A.; Cox, G.; Czerwonogora, A.; Elias, T.; Essmiller, K.; et al. GO-GN Guide to Conceptual Frameworks; Global OER Graduate Network (GO-GN); The Open University: Milton Keynes, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ravitch, S.M.; Riggan, M. Reason & Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4833-4696-0. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-8039-2274-7. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, T. Addressing Injustices through MOOCs: A Study among Peri-Urban, Marginalised, South African Youth. Ph. D. Thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha, H.K. The Location of Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; ISBN 978-0-415-05406-5. [Google Scholar]

- Crotty, M. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-1-4462-8313-4. [Google Scholar]

- Young, R.A.; Collin, A. Introduction: Constructivism and Social Constructionism in the Career Field. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, F.J.; Rosch, E.; Thompson, E. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-262-26123-4. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, P.; Luckmann, T. The Social Construction of Reality; Anchor: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, H. The Secular City: Secularization and Urbanization in Theological Perspective, Revised ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-691-15885-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, S. Secularism, Hermeneutics, and Empire: The Politics of Islamic Reformation. Public Cult. 2006, 18, 323–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P. The Desecularization of the World: Resurgent Religion and World Politics; William, B., Ed.; Eerdmans Publishing: Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-8028-4691-4. [Google Scholar]

- Karpov, V. Desecularization: A Conceptual Framework. J. Church State 2010, 52, 232–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Attas, S.M.N. Islam and Secularism; Art Printing Works Sdn.Bhd: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1978; ISBN 983-99628-6-8. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, T. A History of Islam and Science-with Timothy Winter; Royal Institute: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, K.; Khosravi, Z. The Islamic Concept of Education Reconsidered. Am. J. Islam Soc. 2006, 23, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J. Conversations on Embodiment across Higher Education: Teaching, Practice and Research; Routledge research in higher education; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-138-29004-4. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M. The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-226-40317-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, M. The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-674-00070-4. [Google Scholar]

- Derry, J. Technology-Enhanced Learning: A Question of Knowledge. J. Philos. Educ. 2008, 42, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McDowell, J.H. Mind and World; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-674-57610-0. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Door, V.M. Critical Pedagogy and Reflexivity: The Issue of Ethical Consistency. Int. J. Crit. Pedagog. 2014, 5, 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. Reframing Justice in a Globalizing World. New Left Rev. 2005, 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pogge, T.W. An Egalitarian Law of Peoples. Philos. Public Aff. 1994, 23, 195–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentham, J. Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation; Claredon Press: Oxford, UK, 1789. [Google Scholar]

- Mill, J.S. Utilitarianism; The Floating Press: Auckland, New Zealand, 1863. [Google Scholar]

- Nozick, R. Anarchy, State, and Utopia; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1974; Volume 5038. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, I. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. In Late Modern Philosophy: Essential Readings with Commentary; Radcliffe, E.S., McCarty, R., Allhoff, F., Vaidya, A., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1785. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971; ISBN 978-0-674-88010-8. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M. Capabilities and Social Justice. Int. Stud. Rev. 2002, 4, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandel, M. Liberalism and the Limits of Justice, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-521-56741-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau, W. Western Theories of Justice. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2019. Available online: https://iep.utm.edu/justwest/ (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Nielsen, K. Radical Egalitarian Justice: Justice as Equality. Soc. Theory Pract. 1979, 5, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandel, M.J. Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? 1st ed.; Penguin: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-14-104133-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. From Redistribution to Recognition? Dilemmas of Justice in a’post-Socialist’age. New Left Rev. 1995, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Dachi, H.; Tikly, L. Social Justice in African Education in the Age of Globalisation; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-8058-5928-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hlalele, D. Social Justice and Rural Education in South Africa. Perspect. Educ. 2012, 30, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson-Williams, C.A.; Trotter, H. A Social Justice Framework for Understanding Open Educational Resources and Practices in the Global South. J. Learn. Dev. 2018, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, S.; Enslin, P. Social Justice and Inclusion in Education and Politics: The South African Case. Available online: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/sabinet/joe/2004/00000034/00000001/art00006 (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- Young, I. Justice and the Politics of Difference; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-691-02315-1. [Google Scholar]

- Luckett, K.; Shay, S. Reframing the Curriculum: A Transformative Approach. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2017, 61, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterhalter, E.; Allais, S.; Howell, C.; Adu-Yeboah, C.; Fongwa, S.; Ibrahim, J.; McCowan, T.; Molebatsi, P.; Morley, L.; Ndaba, M.; et al. Higher Education, Inequalities and the Public Good-Perspectives from Four African Countries; UK Research and Innovation: Wiltshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, R. Using Southern Theory: Decolonizing Social Thought in Theory, Research and Application. Plan. Theory 2014, 13, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosfoguel, R. The Epistemic Decolonial Turn. Cult. Stud. 2007, 21, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S.J. Decoloniality as the Future of Africa. Hist. Compass 2015, 13, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Santos, B.S. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-61205-545-9. [Google Scholar]

- Thiong’o, N.W. Europhone or African Memory: The Challenge of the Pan-Africanist Intellectual in the Era of Globalization1. In African Intellectuals: Rethinking Politics, Language, Gender and Development; CODESRIA: Dakar, Senegal, 2005; pp. 155–165. ISBN 2-86978-145-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wronka, J. Human Rights and Social Justice: Social Action and Service for the Helping and Health Professions; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4833-8716-1. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The International Forum for Social Development: Social Justice in an Open World the Role of the United Nations; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, J.-M. Decolonial Thinking and the Quest for Decolonising Human Rights. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 46, 484–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Torres, N. On the Coloniality of Human Rights. Rev. Crítica Ciências Sociais 2017, 144, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, M. Re-Contextualising Human Rights Education: Some Decolonial Strategies and Pedagogical/Curricular Possibilities. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2017, 25, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkrumah, K. Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology for De-Colonisation; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Nkrumah, K. Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism; International Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Rodney, W. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa; Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications: London, UK; Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, S. Accumulation on a World Scale: A Critique of the Theory of Underdevelopment; Monthly Review Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, A. Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality. Cult. Stud. 2007, 21, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignolo, W. Introduction: Coloniality of Power and de-Colonial Thinking. Cult. Stud. 2007, 21, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.M. Suspending the Desire for Recognition: Coloniality of Being, the Dialectics of Death, and Chicana/o Literature. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, W. The Darker Side of Western Modernity Global Futures, Decolonial Options; Latin America otherwise; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-8223-9450-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mbembe, A. Getting out of the Ghetto: The Challenge of Internationalization. Codesria Bull. 1999, 3, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Fanon, F. The Wretched of the Earth; MacGibbon & Kee: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A. Amardeep Singh: Mimicry and Hybridity in Plain English. 2009. Available online: https://www.lehigh.edu/~amsp/2009/05/mimicry-and-hybridity-in-plain-english.html (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Magaziner, D.R. The Law and the Prophets: Black Consciousness in South Africa, 1968–1977; Ohio University Press: Athens, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H.A.; Penna, A.N. Social Education in the Classroom: The Dynamics of the Hidden Curriculum. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 1979, 7, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J. INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW: Making Sense of Decolonisation in Universities. In Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge; Jansen, J., Ed.; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, J. As by Fire: The End of the South African University, 1st ed.; Tafelberg: Cape Town, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mamdani, M. Between the Public Intellectual and the Scholar: Decolonization and Some Post-Independence Initiatives in African Higher Education. Inter-Asia Cult. Stud. 2016, 17, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson-Williams, C.; Arinto, P.; Cartmill, T.; King, T. Factors Influencing Open Educational Practices and OER in the Global South: Meta-Synthesis of the ROER4D Project. In Adoption and Impact of OER in the Global South; International Development Research Centre & Research on Open Educational Resources for Development (ROER4D) project; African Minds: Cape Town, South Africa, 2017; ISBN 978-1-55250-599-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dei, G.J.S.; Simmons, M. Fanon & Education: Thinking through Pedagogical Possibilities; Peter Lang: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4331-0641-5. [Google Scholar]

- Fanon, F. Black Skin, White Masks; Grove Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967; ISBN 978-0-7453-0035-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, L. The Institutional Curriculum, Pedagogy and the Decolonisation of the South African University. In Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge; Jansen, J.D., Ed.; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019; pp. 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Honneth, A. The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mbembe, A. Future Knowledges and Their Implications for the Decolonisation Project. In Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge; Jansen, J.D., Ed.; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019; pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- RMF. The Johannesburg Salon; JWTC: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Makgoba, M.; Seepe, S. Knowledge and Identity: An African Vision of Higher Education Transformation. In Towards an African Identity of Higher Education; Seepe, S., Ed.; Vista University: Pretoria, South Africa, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mamdani, M. Decolonising Universities. In Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge; Jansen, J.D., Ed.; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019; pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hoadley, U.; Galant, J. What Counts and Who Belongs?: Current Debates in Decolonising the Curriculum. In Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge; Jansen, J.D., Ed.; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019; pp. 100–114. [Google Scholar]

- Enslin, P.; Horsthemke, K. Philosophy of Education: Becoming Less Western, More African? J. Philos. Educ. 2016, 50, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chisholm, L.; Soudien, C.; Vally, S.; Gilmour, D. Teachers and Structural Adjustment in South Africa. Educ. Policy 1999, 13, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baatjes, I.G. Neoliberal Fatalism and the Corporatisation of Higher Education in South Africa. Q. Rev. Educ. Train. South Afr. 2005, 12, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach, J.; Dlamini, M. Anonymous Scaling Decolonial Consciousness?: The Reinvention of ‘Africa’ in a Neoliberal University. In Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge; Jansen, J.D., Ed.; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019; pp. 116–135. [Google Scholar]

- Mbembe, A. Decolonizing the University: New Directions. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 2016, 15, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudien, C. Testing Transgressive Thinking: The ‘Learning Through Enlargement’ Initiative at UNISA. In Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge; Jansen, J.D., Ed.; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019; pp. 136–154. [Google Scholar]

- Langa, M.; Ndelu, S.; Edwin, Y.; Vilakazi, M. #Hashtag: An Analysis of the #FeesMustFall Movement at South African Universities. Available online: https://www.africaportal.org/publications/hashtag-an-analysis-of-the-feesmustfall-movement-at-south-african-universities/ (accessed on 13 September 2019).

- Moosa, F. What Are Students Demanding from #FeesMustFall? The Daily Vox, 23 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Laurillard, D. Technology Enhanced Learning as a Tool for Pedagogical Innovation. J. Philos. Educ. 2008, 42, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, W. (Ed.) The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power; Zed Books: London, UK; Atlantic Highlands, NJ, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-1-85649-043-6. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, I.D. Heidegger on Ontotheology: Technology and the Politics of Education; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-521-61659-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.M. Decolonizing Information Narratives: Entangled Apocalyptics, Algorithmic Racism and the Myths of History. Proceedings 2017, 1, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, B. Decolonizing Technology: A Reading List. Beatrice Martini. 2017. Available online: https://beatricemartini.it/blog/decolonizing-technology-reading-list/ (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Knowledge Commons Brasil Digital Colonialism & the Internet as a Tool of Cultural Hegemony|Knowledge Commons Brasil 2014 (no longer available online).

- Danezis, G. The Dawn of Cyber-Colonialism. Conspicuous Chatter. 2014. Available online: https://conspicuouschatter.wordpress.com/2014/06/21/the-dawn-of-cyber-colonialism/ (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Data Colonialism: Critiquing Consent and Control in “Tech for Social Change”. Model View Culture. 2016. Available online: https://modelviewculture.com/pieces/data-colonialism-critiquing-consent-and-control-in-tech-for-social-change (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Simmons, A. Technology Colonialism. Model View Culture. 2015. Available online: https://modelviewculture.com/pieces/technology-colonialism (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Suarez-Villa, L. Technocapitalism: A Critical Perspective on Technological Innovation and Corporatism; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4399-0042-0. [Google Scholar]

- Srnicek, N. The Challenges of Platform Capitalism: Understanding the Logic of a New Business Model. Juncture 2017, 23, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, O. “It’s Digital Colonialism”: How Facebook’s Free Internet Service Has Failed Its Users. The Guardian, 27 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Feenberg, A. Questioning Technology, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-415-19755-7. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, T. Digital Literacy Needs for Online Learning Among Peri-Urban, Marginalised Youth in South Africa. Int. J. Mob. Blended Learn. 2022, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohs, M.; Ganz, M. MOOCs and the Claim of Education for All: A Disillusion by Empirical Data. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distance Learn. 2015, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komljenovic, J.; Williamson, B.; Eynon, R.; Davies, H.C. When Public Policy ‘Fails’ and Venture Capital ‘Saves’ Education: Edtech Investors as Economic and Political Actors. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Trends in Digital Personalized Learning in Lowand Middle-Income Countries: Executive Summary; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, L. Scaling Personalised Learning Technology in Malawi. EdTech Hub. 2021. Available online: https://edtechhub.org/sandboxes/scaling-personalised-learning-technology-in-malawi/ (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Meet Khanmigo: Khan Academy’s AI-Powered Teaching Assistant & Tutor. Available online: https://khanmigo.ai/ (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Czerniewicz, L.; Mogliacci, R.; Walji, S.; Cliff, A.; Swinnerton, B.; Morris, N. Academics Teaching and Learning at the Nexus: Unbundling, Marketisation and Digitisation in Higher Education. Teach. High. Educ. 2023, 28, 1295–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adam, T. A Justice-Oriented Conceptual and Analytical Framework for Decolonising and Desecularising the Field of Educational Technology. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 962. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090962

Adam T. A Justice-Oriented Conceptual and Analytical Framework for Decolonising and Desecularising the Field of Educational Technology. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(9):962. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090962

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdam, Taskeen. 2024. "A Justice-Oriented Conceptual and Analytical Framework for Decolonising and Desecularising the Field of Educational Technology" Education Sciences 14, no. 9: 962. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090962

APA StyleAdam, T. (2024). A Justice-Oriented Conceptual and Analytical Framework for Decolonising and Desecularising the Field of Educational Technology. Education Sciences, 14(9), 962. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090962