Abstract

Teacher turnover remains a challenge in education. We reviewed 85 studies conducted in the United States and around the world to better understand teacher turnover causes. We initially screened 290 articles published from 1994 to 2024. The most known factors of teacher turnover were sought through analysis of last 30 years quantitative research. Our study addressed the reasons behind teacher turnover and how each factor affects teacher turnover. The analysis was conducted to quantitatively determine suggested factors of teacher turnover and retention. The Preferred Reporting Items for the Systematic Review of the Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement were used to follow literature review guidelines. The findings revealed the critical factors of teacher turnover and supported expanding a conceptual framework for teacher turnover causes in various contexts. The framework highlights the interactions among personal factors, workplace characteristic factors, and job characteristic factors. The findings highlight that leadership quality, teachers’ years of experience, student characteristics, school level, and teacher ethnicity are significant predictors of teacher turnover.

1. Introduction

Teacher turnover has been a challenging issue in America for about a half century as well as being a significant concern for many countries across the globe (Nguyen & Springer, 2023). Teacher turnover significantly effects on student learning and achievement and replacing experienced teachers with novice teachers is costly for education system (Jones-Presley, 2023; Stock & Carriere, 2021; Taie & Lewis, 2023). Although some educational legislative acts previously were adopted to enhance the quality of the teaching workforce and address the concerns of teachers about not being qualified, as well as concerns about student outcomes, the problem of teacher turnover still exists. For instance, although the U.S. federal No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) in 2002 required elementary and secondary schoolteachers to have at least a bachelor’s degree and be certified in their field, the concern for the position of teacher exists (Wronowski & Urick, 2019). Moreover, qualified teachers need to be equally distributed in elementary and secondary school levels (Buckman, 2021). The issue of teacher turnover requires governments around the world to invest and devote more resources to education system to retain teacher. Such investments increased the number of research studies exploring factors influencing teacher turnover. The NCLB and Every Student Succeed Acts (ESSA) supported investment in recruitment and retention of qualified teachers in schools. The term factor refers to teachers’ personal factors, workplace conditions, and job characteristics acquainted with turnover.

In the meta-analysis of teacher turnover conducted by Borman and Dowling (2008), they referred to personal and qualification characteristics, school characteristics, and job characteristics as causes of teacher turnover. More recently, Räsänen et al. (2020) referred to personal, professional characteristics, and work conditions as influential causes of teacher turnover. The meta-analysis of teacher turnover by Nguyen et al. (2020) highlighted that teacher turnover was related to three correlates: personal, school, and external. Building on what we know about previous meta-analyses of teacher turnover factors and knowing the results of new studies in the context of previous studies, we proposed that a meta-analysis of teacher retention literature is required to connect the existing knowledge on teacher turnover characteristics and potential shifts in teacher turnover factors and sub-factors across three last decades ending in 2024 including during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. To address this gap, the authors of the current study reviewed the latest quantitative studies related to teacher turnover factors to address the following research questions:

- What precedent teacher turnover factors are still relevant and what new factors emerged under recent global circumstances?

- To what extent are these factors associated with teacher retention?

1.1. Teacher Turnover Problem

Teacher turnover continued to increase after 2019–2020 school year when the turnover rate was 10%. Reports of teacher turnover demonstrate that the teacher turnover rate is more than 16% across America including 8% leavers and 8% movers to other schools (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019). Scrutinizing national data on teacher turnover, Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2017) found that more than two-thirds of teachers leave the profession for reasons other than retirement. They also highlighted that recruiting and training novice teachers cost about $20,000 each. Training novice teachers is more expensive than keeping experienced teachers in the profession (Almas et al., 2020). Ingersoll et al. (2019) analyzed turnover data and concluded that among all teaching profession leavers, 10% leave in year one due to dissatisfaction with schools as a sub-factor of work condition, family as a sub-factor of personal factor, pursuing another career, and involuntary exclusion for weak performance. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, teacher attrition is higher than in other careers including pharmacists, engineers, lawyers, nurses, architects, and police officers (Räsänen et al., 2020).

Years after World War II in 1980s, the baby boom and the aging of the teacher workforce raised the concern of teacher turnover (Darling-Hammond, 1984). To understand the causes of teacher turnover, scholars conducted a variety of research methods including quantitative research using surveys or analysis of administrative data, meta-analysis, narrative reviews, and qualitative studies to find the reasons behind teacher turnover. As early as the 1980s, Cotton and Tuttle (1986) stated that turnover was related to personal, work, and external correlates. Later, Ingersoll (2001) highlighted that teacher shortage was not related to an increasing number of retirees and stated that teacher shortage was due to the increasing number of teachers who left their career. A narrative review of the literature by Cotton and Guarino et al. (2006) revealed some significant factors of teacher retention such as gender, ethnicity, academic ability, years of experience, teaching field, student demographics, salary, incentive, and policies. Harris and Adams (2007) claimed that, experienced teachers leave their career at a higher rate comparing to other professions including nurses, accountants, and social workers.

1.2. Development of Meta-Analysis Studies

Teacher turnover literature was expanded during 2008 to 2023 through meta-analyses by prominent scholars. The most remarkable meta-analysis of teacher turnover and retention was conducted by Borman and Dowling (2008). They categorized teacher retention factors into (a) personal and qualification characteristics, (b) school characteristics, and (c) job characteristics. The results of Borman and Dowling (2008) study revealed that female; White; young; married; and teachers who have a child were more likely to quit their jobs. Additionally, they highlighted that science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) teachers; less experienced; and uncertified teachers were more prone to turnover and attrition.

Borman and Dowling (2008) stated that teacher collaboration, networking, and administrative support were moderators of turnover and attrition in schools with high enrollments of students with divers backgrounds. School administrators could support teachers in many ways, including assisting teachers with issues such as student discipline, instructional methods, curriculum, and adjusting to the school environment. Regarding job characteristics, Borman and Dowling (2008) stated that salaries and equal distribution of instructional resources were moderators of teacher turnover.

Nguyen et al. (2019) categorized teacher retention factors into (a) personal correlates including teacher characteristics and qualifications, (b) school characteristics, school resources, and student body characteristics and (c) eternal correlates. They highlighted that Black, Hispanic, and minority non-White teachers, regularly certified teachers, and satisfied teachers were less likely to leave the profession. They further revealed that principal effectiveness and support, professional engagement, access to school resources and facilities, full-time jobs, a small number of minority students, principal-teacher congruence, teacher–student congruence, and higher achiever students were school characteristics that reduced teacher turnover. Additionally, they referred to accountability and workforce as external factors of turnover.

Comparing the two previous meta-analyses, Nguyen et al. (2019) claimed that there was no difference between female and male teachers’ turnover rates while Borman and Dowling (2008) stated that the odds of turnover were significantly higher among female teachers than male teachers. Additionally, Nguyen et al. (2019) did not find a significant difference in turnover rate between someone who has a graduate degree and someone without a graduate degree while Borman and Dowling (2008) concluded that teachers with graduate degrees were more likely to leave their profession. Nguyen et al. (2019) findings aligned with Borman and Dowling’s (2008) suggesting a higher turnover rate among STEM and special education teachers.

More recent research highlighted some persuasive factors of teacher turnover including (a) the effect of teacher turnover on students’ outcomes and achievements, (b) teachers’ emotional challenges, and (c) the costs of novice teacher recruitment to the education system (Stock & Carriere, 2021). Nguyen and Springer (2023) considered personal factors as teacher characteristics and teacher qualifications. They categorized school factors into school characteristics, school resources, student body characteristics, relational demography, and school organization. Moreover, they identified research, practice, and policy as external factors correlated with teacher turnover and retention. They also defined accountability, workforce, and school improvement as implications of external factors. We conducted our meta-analysis based on Borenstein et al.’s (2021) rationale, who emphasized that a meta-analysis of the literature can be conducted by as few as two studies and as far as one or two years after the previous meta-analysis on the topic. The present meta-analysis of quantitative studies was conducted to identify how teacher retention and turnover were influenced by various factors during the last three decades ending in 2024.

1.3. COVID-19 and Teacher Turnover

One of the other external factors that profoundly affected the education system was the COVID-19 pandemic. The teacher turnover rate increased by 1% during the pandemic. Teacher turnover increased from 6.4% in the 2019–2020 school year to 7.3% in 2020–2021. However, these rates were within the range of teacher turnover rates before the pandemic (Goldhaber & Theobald, 2022). During the pandemic, the differences between high and low poverty schoolteacher turnover rates were less than pre-pandemic. COVID-19 negatively affected special education teachers by overloading their work and creating challenging times for supplying student resources (Hurwitz et al., 2022). Special education teachers had to create a virtual learning environment that addressed a broad spectrum of students with disabilities, and they found the new situation a challenging time for themselves. However, a challenging environment usually has less effect on novice teachers who have higher levels of resilience in challenging situations (Gunn et al., 2023).

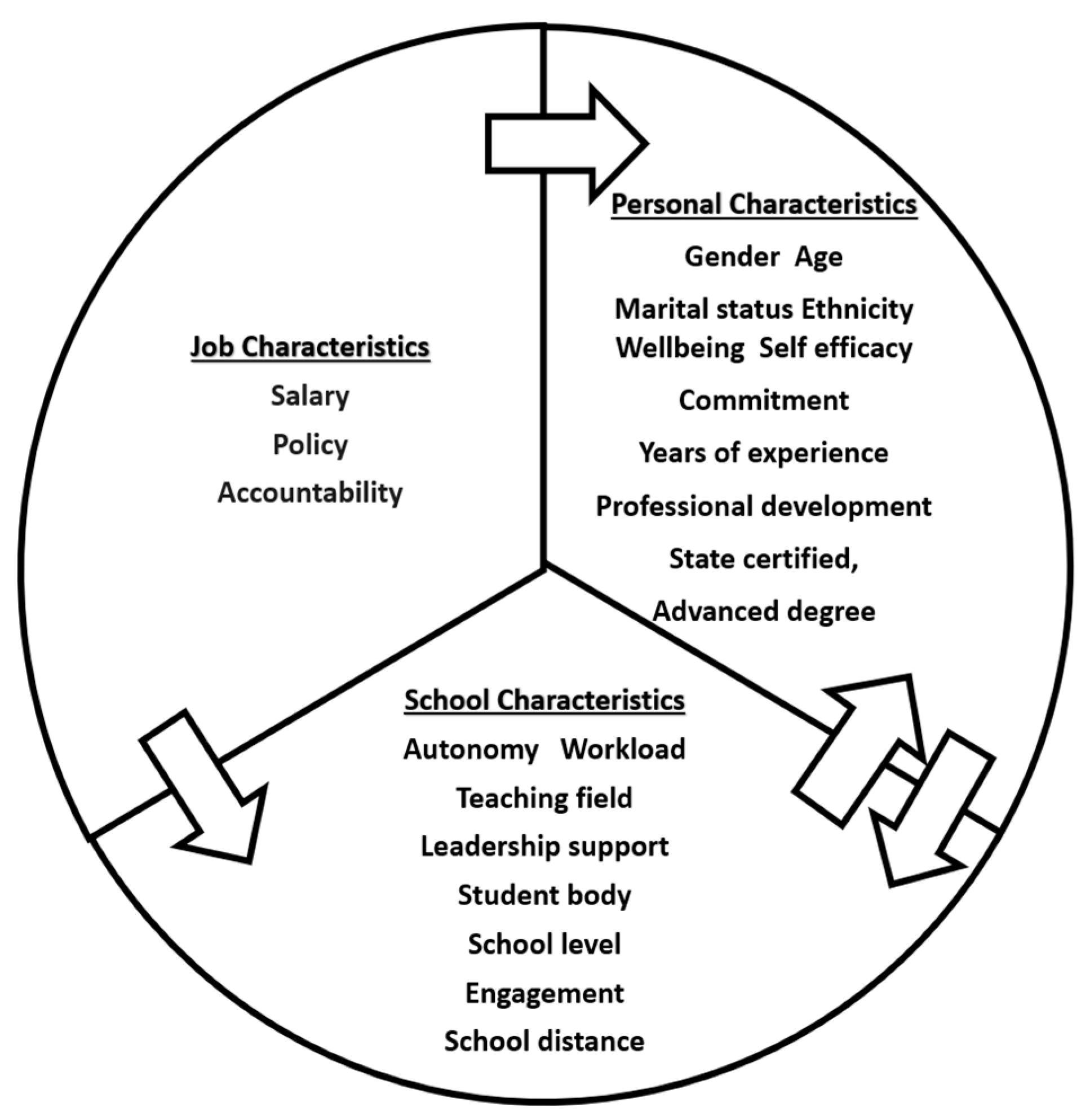

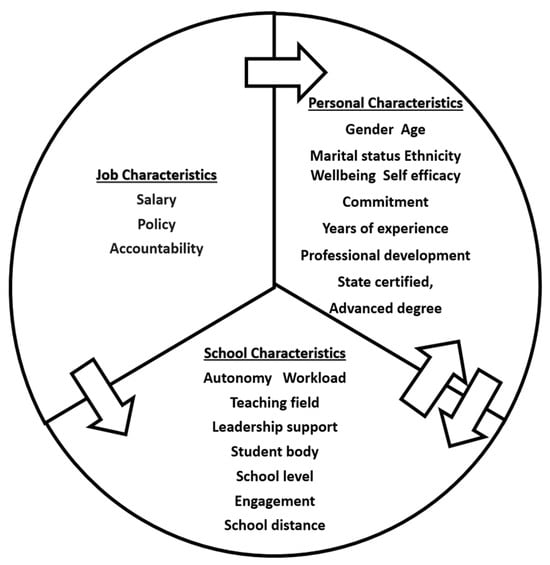

1.4. Teacher Retention Conceptual Framework

To illustrate the relationship between teacher turnover variables including personal, school, and job characteristics, a conceptual framework is designed. The conceptual framework shown in Figure 1 mapped out the main factors contributing to teacher turnover Understanding these factors is crucial for developing strategies to enhance teacher retention. This framework demonstrates that personal and school factors have a mutual effect on each other. Job factors also affect personal and school factors. However, the analysis of articles included in the present study did not refer to the effect of personal and school factors on job factors. Moreover, each of the three factors individually affects teacher retention and turnover.

Figure 1.

Teacher retention framework.

2. Methodology

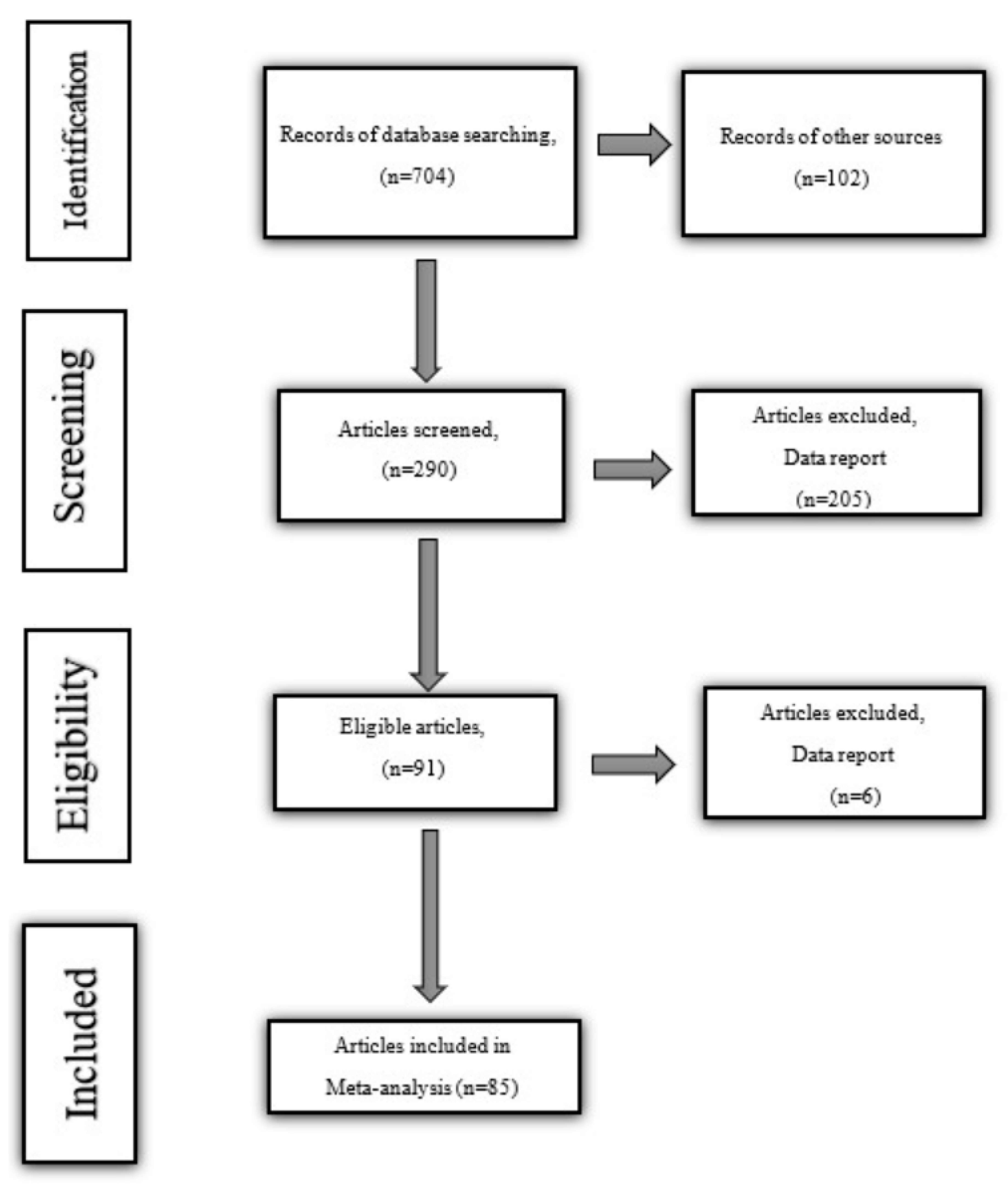

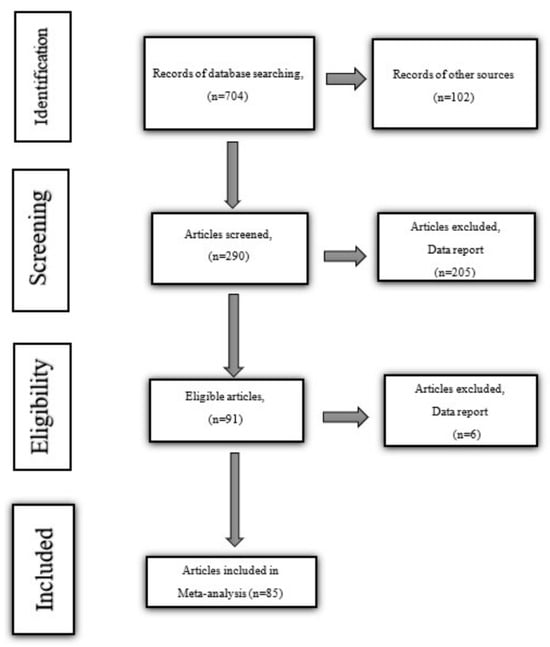

The analysis was conducted to synthesize quantitatively estimated factors of teacher turnover and retention. To follow the framework, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement was utilized (Page et al., 2021). Utilizing the PRISMA framework, the eligibility criteria of the articles were examined. The research method was in stages: (1) development of eligibility criteria that lead to the inclusion and exclusion of studies, (2) information source or database search for relevant studies, (3) search strategy, (4) selection process, (5) data collection process, (6) study risk of bias assessment, (7) effect measures, (8) synthesis method reporting bias assessment, (9) certainty assessment, and (10) results, discussion, registration, and protocol development.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

To select appropriate studies, the following eligibility criteria were determined. (1) We first sought full-text articles within the timeframe of 1994 to 2024. The research design appropriateness was checked with the proposed objective of our study. (2) We then searched for subject appropriateness with teacher turnover and retention factors. (3) We next chose articles with sample sizes of about or more than 50 participants who served in K-12 education. (4) Data measurements included odd ratios, logistics, and p values, (5) We affirmed that the research was conducted in the United States and across the globe. Through our research, we found articles from other contexts including China, England, Finland, and South Africa, that were included in our analysis (6) Then, longitudinal, one-factor, and multifactor teacher turnover research sources were included. We reviewed the research that focused on either of the three main factors of teacher turnover or any combination of these factors. In the second step, articles related to other careers were excluded. We excluded the non-primary articles including meta-analytic from our study because their analytic methods were different from our approach. Also, non-empirical articles which did not identify a measurable outcome of teacher retention were excluded. Last, we omitted articles other than English-language, articles related to contexts other than education.

2.2. Search Strategy and Selection Process

To find related studies, the following databases were chosen. The Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, EconLit, Education Source, and ERIC were sought as the main sources (Appendix A). We also searched ProQuest, Google Scholar, and Nexic Uni. The following search string was used to include the articles: “Teacher” and “Turnover” or “Attrition” or “Retention” or “Mover” or “Leaver”. A total number of 806 articles appeared within the databases and other search sources, including Google Scholar and ProQuest. While 250 of the articles investigated the issue of turnover in education, other articles sought turnover in other organizations, including hospitals and armed forces, and other topics related to teachers. Excluding qualitative research generated 16 quantitative articles related to education. Two of the articles were meta-analytics, so eighty-five articles provided numerical results.

To follow the guidelines of the method, we reviewed each article’s topic, abstract, job similarity as a controller for work and job conditions, introduction, study design, method, population, and sample. We sought for teacher, school, and job characteristic factors demonstrated in studies. In the second stage, we checked for the data collection sources’ and tools. Figure 2 depicts that process.

Figure 2.

Flow information through a systemic review of the literature screening process. Adapted from Mayo-Wilson et al. (2018).

2.3. Data Collection Process

Articles included in our study mostly used national administrative data sources or standardized questionnaires as their data collection tools. We checked the data analysis procedures, including descriptive statistics, using correlations to include them in our analysis. Considering all those criteria, we included 85 articles to find the results and guide discussion and conclusion sections. In the next step, the factors derived from each article were counted and categorized. Also, the number of each sub-factor in all articles was counted and reported.

3. Analytic Strategy

Studies differ in how they report measurements of the factors. For instance, different descriptive statistics might be used to report findings, including means, percentages, proportions, standard deviations, odd ratios, standard errors, correlations, and p-values. Meta-analysis calculates the weighted average of the effect size, not the arithmetic means between studies (Sen & Yildirim, 2022). The effect size tells us how meaningful the relationship between variables and differences between groups is, and if the effect is significant enough to be meaningful when applied to the real world. It is important to mention that not all the studies we reviewed have the same value. For instance, some of the studies included a greater number of participants, so they weighed more than those with fewer participants. To weigh the articles, we needed to measure the combined effect. Either the fixed effects or random effects model could be used to measure the combined effect. The fixed effect model assumes that all studies in an analysis were equally precise and there was only one actual effect size for all studies; this one effect size is defined as the combined effect size. Based on the fixed effect model, large studies give the most significant portion of the weight (Borenstein et al., 2021). In the fixed effect model, there is only one source of error which is random error within studies. In large sample sizes, the error tends toward zero. On the contrary, the random effects model assumes that there are random distributions of effects in different studies, and the mean of a distribution of exact effects is estimated as a combined effect. Based on the random effects model, two levels of sampling and two levels of error exist.

We created multiple Excel sheets to record the data reported with either raw data that included sample sizes, means (M), proportions, and standard deviations (SD), or effect sizes including odd ratios and standard errors, as well as correlations and variances. Overall, most of the data on the Excel sheets were reported as odd ratios and some as correlations and few included means and standard deviations. As the effect sizes should be consistent across the studies, we converted correlations into log odd ratios (LOR) (Borenstein et al., 2021). To convert between different types of effect sizes, we used online calculators accessible on Scale or Psychometrika websites. As the log odd ratios range between negative infinity and positive infinity, we had less trouble interpreting the results. The log odd ratios that had higher values indicate a stronger association with outcomes which, in this paper, are teacher turnover factors and turnover itself. Using log odd ratios enabled us to interpret data in SPSS 29 which is a more accessible statistical software.

We also knew that the observed disparities in effect sizes were due to the sampling variation and other sources of variability rather than the difference in true effect sizes, as explained by Borenstein et al. (2021). As each selected study had a different population and different effect sizes, we applied a random model effect size. For pre-calculated effect sizes, we used the pre-calculated sub-menu under the menu of binary outcomes in SPSS 29 to determine the mean effect size, its standard error, Z-value, two-tailed p-value, and 95% confidence interval, as proposed by Sen and Yildirim (2022) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effective sizes of selected studies related to each retention factor.

The mean and standard deviation of the binary groups were converted into log odd ratio using the following equation:

where and are p-values for binary groups.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients (r) were converted into log odd ratio using the following equation:

Log Odd Ratio = log (1 + R/1 − R)

3.1. Study Risk of Bias

Studies might show high effect sizes due to multiple sub-factors cause teacher turnover (Borenstein et al., 2021). To address the issue, we controlled for the high effect sizes and we did not find any study with high effect sizes for all variables. We controlled for the studies that might be published more than one time due to reporting higher effect sizes. Inclusion criteria bias happens when the researcher relies overly on electronic sources. As the electronic sources were the only sources we used to search for articles, there might be articles that had been in the scope of our analysis but not included in the study. We used databases which were available to us, so there might be some missing databases as well as some studies. Sample bias might also happen when the missing studies are different from those included in the analysis. Additionally, the studies in languages other than English were omitted meaning that the study might have language bias.

3.2. Publication Bias

Due to many sub-factors that cause teacher turnover, studies might show unreal and high effect sizes to be published (Borenstein et al., 2021). We controlled for the relatively high effect sizes. We did not find any study where all reported effect sizes were high. We checked for the studies that might be published more than one time due to demonstrating higher effect sizes. Inclusion criteria bias happens when the researcher relies overly on electronic sources. We controlled for the studies published more than once due to reporting higher effect sizes. As the electronic sources were the only sources we used to search for articles, there might be articles that had been in the scope of our analysis but not included in the study. The utilized databases were available to us but not all available databases, so there might be some missing studies. The missing studies might be systematically different from those included in the analysis thus our sample might be biased. We eliminated the studies in languages other than English which means the study might have language bias.

4. Findings

The meta-analytic of teacher turnover factors declares teacher turnover causes. The first research question asks about factors associated with teacher turnover. A total of 85 quantitative studies were selected that relied on district, state, and national data. We found two trends in the literature review: (1) the approaches directly addressed the problem of teacher retention and turnover, including studies focusing on personal, school, and job factors; and (2) indirect approaches included studies focused on school reforms. To answer the second research question, the effect sizes of each factor were reported as an indicator of the extent of association between the personal, school, and job factors of teacher turnover and teachers’ decision to remain in their profession. In the following paragraphs, we provide answers to both questions.

4.1. Results for Factors Associated with Teacher Turnover

In this study, we used meta-analysis techniques to present the main factors associated with teacher turnover and retention. Building on our analysis of 85 articles, we found three teacher turnover factors which we discuss in the following paragraphs: personal, school, and job characteristics.

4.2. Results for Personal Factors

The present meta-analytic findings highlight personal factors associated with teacher retention as teacher gender, age, marital status, race, certification, years of experience, wellbeing, commitment, self-efficacy, and professional development. Among all personal factors, teachers’ professional development (LOR = 3.089, p-value = 0.622) and holding state certification (LOR = 2.422, p-value = 0.059) were stronger predictors of teacher turnover and showed higher log odd ratios compared to other personal factors, though they are not marginally significant. The findings of our study indicate that gender does not significantly affect teacher turnover (LOR = −0.070, p-value = 0.608). The result for the age shows a positive effect on turnover, although not statistically significant (LOR = 1.115, p-value = 0.165). Marital status (LOR = −0.162, p-value = 0.240) did not significantly influence turnover, as indicated by small effect sizes and non-significant p-values. The reported data throughout studies regarding teachers of color turnover reveals that race has a positive effect on turnover but not significantly (LOR = 0.019 p-value = 0.931). It can be inferred from the data presented in Table 1 that experienced teachers were less likely to leave their profession (LOR = −0.351, p-value = 0.027) and the results were statistically significant (De Clercq et al., 2022). Compared to experienced teachers, results for novice teachers appeared to cause higher odds of turnover (LOR = 0.668 p-value = 0.302), but not statistically significant. Wellbeing had a positive but not significant effect on teacher turnover (LOR = 0.612, p-value = 0.336). Teachers’ perceptions of their school environment were more robust drivers of their turnover than their colleagues’ perceptions, as noted by Grant and Brantlinger (2022). Commitment to the students and job rate were small in log odds and small in statistically significant effect on teacher turnover (LOR = 0.474, p-value = 0.699). Self-efficacy was determined to have a positive effect on turnover but not significantly (LOR = 0.474, p-value = 0.699). Apparently, the odds of turnover are higher for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics teachers (STEM) (LOR = 0.190, p-value = 0.558) and special education teachers (LOR = −0.940, p-value = −0.310) but still not statistically significant. Mathematics, science, special education, and foreign language teachers are more likely to quit their jobs in schools with high poverty and low-income students because students need more attention, and it creates more workload for teachers, according to Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2019).

4.3. Results for Workplace Factors

As shown in Table 1, school organizational characteristics affecting turnover included autonomy, school distance, leadership support, student body characteristics, school location, school poverty, and school level. The findings of this study reveal that among all the school factors, autonomy (LOR = 211.869, p-value = 0.364) and leadership quality (LOR = 35.196, p-value = −0.020) have a significant positive impact on teacher turnover. Having autonomy in performing job requirements increases teachers’ retention. The findings also indicate that supportive leadership strongly influences teacher retention. The outcomes highlight the importance of the geographic closeness of teachers’ homes to the school (LOR = 35.734, p-value = 0.077), yielding a large positive impact on teacher retention. Edwards (2024) emphasized that findings on hometown novice teachers presented a higher predicted probability of remaining in their current school after one, three, and five years of teaching, compared to all other novice teachers. School location significantly affects turnover, and urban schools (LOR = 1.380, p-value = 0.263) are more likely to experience teacher turnover than rural areas (LOR = 0.888, p-value = 0.414). In favor of data, accountability (LOR = 0.720, p-value = 0.000) is associated with turnover but lacks sufficient data for a conclusive interpretation of the p-value. The results related to student body characteristics (LOR = 0.011, p-value = 0.002) indicate that although the effect size is not as high, poor student behavior is significantly associated with a higher turnover rate. Teaching in middle school (LOR = −2.539, p-value = 0.001) has a small effect size but is significantly associated with a lower turnover rate. Teacher turnover in high schools (LOR = −0.987, p-value = 0.035) has a higher effect size compared with turnover in middle schools and is significantly associated with a lower turnover rate. The workload had a large negative log odd ratio but did not significantly affect teacher turnover (LOR = −144.327, p-value = 0.373). Data provide evidence of a small log odd ratio and non-significant rate of school poverty (LOR = −0.073, p-value = 0.456).

4.4. Results for Job Factors

Job factors refer to external factors of teacher turnover (Ingersoll et al., 2019). The present meta-analytic highlights salary and policy as job factors associated with teacher turnover factors. The data in Table 1 reveal that salary (LOR = −144.327, p-value = 0.373) shows a high negative effect but is not statistically significant on teacher turnover. Moreover, data analysis of the log odd ratio regarding policy implications (LOR = −144.327, p-value = 0.373) highlights that policy has a large negative effect on turnover, but due to the lack of studies on the effect of policy on teacher turnover, we are unable to determine any significance. Aligning with the findings of the current study, Kafumbu (2019) found a negative moderate correlation between policy and teacher turnover.

5. Discussion

Our study identifies new personal and school turnover factors among teachers. While the present study consolidates some of the previous findings of teacher turnover literature by Borman and Dowling (2008) and Nguyen et al. (2019), it also highlights contrary and new factors of teacher turnover. Our analysis declared that new global challenges led scholars to focus on personal and school factors more than ever before including the effect of wellbeing, teacher commitment, teacher self-efficacy, autonomy, workload, and distance from school.

5.1. Gender, Age, Marital Status, and Turnover

The findings of this study reveal that no significant relationship exists between teacher turnover and gender and marital status, which aligns with the findings of Nguyen et al. (2020) and Solomonson et al. (2022). On the contrary, Borman and Dowling’s (2008) findings highlighted a meaningful difference between female and male teachers’ turnover. In terms of marital status, the outcomes of this study do not show any significant relationship between teachers’ marital status and their turnover, as recently suggested by Solomonson et al. (2022). On the contrary, Nguyen et al. (2020) suggested that married teachers are more likely to quit their jobs. Teaching is a fundamental profession shaping the future of societies. Women who were culturally excluded from other professions were found to be practically good fit for education specifically at elementary and middle schools. However, there is a historical belief that female teachers leave their profession at a higher level than male teachers (Gunter, 2024).

5.2. Race and Turnover

The present study results show statistically significant differences in the retention and mobility rates of Latinx teachers compared to Black teachers. Teachers of color or Latinx teachers stay longer at schools with more students with the same background (Elfers et al., 2022). Additionally, the findings of this study reveal that teachers of color are more likely to quit their jobs. Student-to-teacher ethnicity congruence can be a predictor of teacher turnover, meaning that when students and teachers are from the same ethnicity, the chances of leaving are reduced. Teachers of color are more willing to leave their schools and move to another school (Elfers et al., 2022). Moreover, schools with higher proportions of students of color are more prone to teacher attrition (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019; Ingersoll et al., 2019). Variance in ethnicity and race has important implications for policymakers to diversify the teaching workforce. Additionally, further research is needed to explore the causes of higher turnover among White and Latinx teachers.

5.3. Certification, Experience and Turnover

Teacher certifications were discussed in the chosen articles indicating that state-certified teachers represent higher occupational commitment compared to non-degree and non-certified teachers (Grant & Brantlinger, 2022; Solomonson et al., 2022). Borman and Dowling (2008) defined qualified teachers as teachers who had graduate degrees, were specialists in mathematics or science, held regular certifications, had more years of experience, or achieved higher scores on some standardized tests. They stated that the odds of turnover were greater among all types of qualified teachers except for teachers with degrees and higher scores in standard exams. They found that qualified teachers were less likely to leave their profession.

Regarding experienced teachers’ turnover, the present study’s findings align with the findings of the Nguyen et al. (2020) meta-analysis, meaning that as teachers’ years of experience increase, the likelihood of retention increases. On the contrary, Borman and Dowling (2008) claimed that experienced teachers leave their profession at a higher rate. Comparing teachers serving in wealthy districts with teachers serving in low-income districts, experienced teachers might be less willing to quit their profession in wealthy districts due to the higher tax revenue (Gunter, 2024).

5.4. Wellbeing and Turnover

Our findings regarding the effect of wellbeing on teacher turnover indicate that wellbeing has a positive but not significant effect on teacher turnover. Our analytics highlight that teacher wellbeing has been a concern in teacher turnover studies around the globe in recent years because the number of studies focused on wellbeing as a personal factor of teacher retention has increased compared to previous meta-analyses. Collie (2023) claimed that school resources facilitated teachers’ autonomy as it is related to students’ needs and positively affects teachers’ wellbeing and retention. In another study, Vincent et al. (2023) stated that insufficient resources negatively affected teachers’ workplace engagement and psychological wellbeing and led to burnout. Madigan and Kim (2021) also emphasized that exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced accomplishment were highly important in predicting teachers’ intentions to quit. Perceiving positive distress, regulating emotions, and coping with work conditions have been the focus of scholarly research (Kafumbu, 2019; Mullins, 2024; Räsänen et al., 2020).

5.5. Commitment and Turnover

Commitment to the teaching is one of the significant factors of teacher retention (Ingersoll et al., 2019; Räsänen et al., 2020). Commitment is defined as strength of an individual’s tendency to be involved in an organization (Zhan et al., 2023). Teachers coming from the same community are more likely to stay. For instance, minority teachers are highly motivated to serve in schools with more minority students because they feel more committed to their communities (Ingersoll et al., 2019). Experienced teachers have considerably higher levels of occupational commitment and work engagement than those in the novice or mid-career professional. Work engagement also increased occupational commitment (Solomonson et al., 2022). The study emphasizes the role of commitment in teacher retention. Governments need to invest in the professional development of educators to strengthen their engagement.

5.6. Self-Efficacy, Professional Development, and Turnover

Self-efficacy is determined as having a positive effect on turnover but not significantly. Higher levels of distress and the sense of helpless lead to turnover while higher level of self-efficacy and positive stress increases teacher retention (Marais-Opperman et al., 2021). The current study’s findings about professional development align with the findings of Nguyen et al. (2020). Our findings indicate that among all other personal factors of turnover, professional development shows the highest log odd ratios. Nguyen et al. (2020) defined qualified teachers as teachers who were state-certified teachers or graduated from universities and claimed that professional development reduced the odds of leaving by 16 percent.

5.7. Special Education, STEM Teachers, and Turnover

The review of articles highlights that STEM and special education teachers are more likely to leave their profession. Accordingly, Nguyen et al. (2020) affirmed that STEM and special education teachers are more likely to quit their jobs. Borman and Dowling (2008) also highlighted that STEM teachers left their profession at a higher rate than special education teachers.

5.8. Leadership, Autonomy, and Turnover

The findings of the study reveal that among all the school factors, leadership quality and autonomy have a significant positive impact on teacher turnover. Our study outcomes reaffirm that the school leader role is crucial in increasing teacher retention by engaging them in professional activities. The study findings align with earlier meta-analytics of Borman and Dowling (2008) and Nguyen et al. (2020) conveying that school leaders play an essential role in keeping teachers at school. Accordingly, Nguyen et al. (2020) found that the odds of retention in schools with more robust leadership support are 80% higher than the odds of turnover among teachers serving in schools with weaker leadership support. School leadership style affects teacher turnover and retention in different ways (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019; De Clercq et al., 2022; Ingersoll et al., 2019). Moreover, supportive school leadership is supposed to reduce the adverse effects of workplace pressure and work overload on teachers (De Clercq et al., 2022). Previous meta-analytics of teacher turnover also showed that administrative support created a positive school environment that increased teacher retention (Borman & Dowling, 2008). We suggest that strengthening leadership support and establishing clear, supportive policies can cultivate a more stable workforce. Autonomy makes teachers feel empowered and increases their retention (McConnell & Swanson, 2024). Having a sense of agency and engaging in professional activities could increase teacher retention (Collie, 2023; De Clercq et al., 2022).

5.9. Student Body Characteristics

The current meta-analytic of teacher turnover factors revealed that students’ body characteristics are positively and significantly associated with a higher teacher turnover rate (LOR = 0.011, p-value = 0.002). Students’ demographics and behavior are other noteworthy factors of teacher turnover. Research declared that students’ behavior increased teacher turnover in low-income, high-minority urban schools (Grant & Brantlinger, 2022). Students’ mistreatment of their teachers and experiences of victimization by teachers contribute to their turnover (Curran et al., 2019; Ingersoll et al., 2019). In terms of the effectiveness of school discipline on student body characteristics and consequently on teacher retention, the findings of this study align with the findings of the meta-analytics of Borman and Dowling (2008), emphasizing that when teachers feel supported by the school administration, the odds of turnover are reduced. School discipline can indirectly and positively affect teacher retention, specifically in low-performing schools, since specific students’ offensive behaviors can be controlled and teachers feel more safe and secure in such schools (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Nguyen et al., 2020; Moon et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2019). In some contexts, student discipline is categorized under leadership support. The study findings affirm that student body characteristics highly affect teachers’ retention. Fostering positive student behaviors can create a more safe and conducive learning environment for both teachers and students.

5.10. School Level, Location, and Turnover

The study findings indicate that teacher turnover is significantly associated with school level and location. Middle school teachers are more likely to leave their profession than high school teachers. Similarly, urban schools are more likely to experience teacher turnover than rural areas. Scholars referred to school level and geography as predictors of teacher turnover (Buckman, 2021; Guthery & Bailes, 2022; Ingersoll et al., 2019). Miller (2019) suggested that teachers were more likely to remain committed to the schools in rural areas. Teachers’ turnover rate is higher in low-income, high-minority urban schools (Grant & Brantlinger, 2022; Ingersoll et al., 2019).

5.11. School Resources, Community, and Turnover

We could not find any studies focusing on school resources and community; however, as these factors are interwoven with other teacher factors, including principal retention, we discuss them here. Scholarly studies emphasized the importance of these factors on teachers’ decision to remain in their current school, such as the study by Collie (2023). Elfers et al., (2022) identified factors including defined school resources as supplying sufficient teaching materials for teachers as highly affecting teachers’ decision to stay or leave their current school. School context is another predictor of teacher retention. Schools with more robust union contexts experience less teacher turnover than those with weaker contexts (Nguyen et al., 2023). Community and within-classroom factors are the strong influences on the decision to remain in the district (Derges, 2024).

The study’s findings revealed that connections to colleagues reduce teacher turnover (Collie, 2023; Engelke, 2023). Moreover, a higher quality of teachers’ relationships with their colleagues can positively affect teacher retention. School climate conditions, including teacher collegiality, increase teacher retention (Grant & Brantlinger, 2022). However, See et al. (2020) could not find any positive relationship between mentoring, support, and induction and teacher retention. Nguyen and Springer (2023) referred to surrounding people, connections, school culture, and school environment as workplace conditions that affect teacher retention. Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2017) emphasized other workplace conditions, including smaller class sizes and more notably educational investments, and their positive effect on teacher retention rate. Other school characteristics are predictors of teacher retention (Buckman, 2021), such as school level and the geography of the region. Retention analysis implies that when teachers feel aligned with the school context and are supported by the school community, they prefer to stay at the same school. Teachers’ connections, integration, and relatedness to their colleagues can be more effective than mentoring (Gunter, 2024).

5.12. Salary, Policy, and Turnover

Among the 85 studies reviewed in the current meta-analysis, very few studies pointed to salary and incentives as predictive factors of teacher turnover. Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2017) emphasized that teacher salary affected an average teacher attrition reduction in a decade after increasing school finance reforms. Teacher salary is defined as metrics of teacher qualification and teachers with higher merit pay are considered as qualified teachers in some regions. Research indicated that overqualified and underqualified teachers are more likely to leave their career (Ingersoll et al., 2019; Ryu & Jinnai, 2021).

The states that offer higher teacher pay and invest more in education experience lower teacher attrition rates (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017). High-poverty districts meet higher turnover of both teachers and leaders because they cannot afford to pay as much as wealthy districts. Additionally, offering financial incentives positively affects teacher commitment in hard-to-staff schools (See et al., 2020). Teacher merit pay indirectly affects student achievement by increasing qualified teachers’ retention (Nguyen et al., 2023). The earlier meta-analytics affirm the current research findings regarding the relatedness of teachers’ salaries to their decision to stay or leave. Borman and Dowling (2008) stated that teacher salary is a strong predictor of teacher retention among experienced teachers.

Quite a few studies devoted effort to exploring the effects of policies on teacher turnover. The analytics of this study demonstrate a positive association between accountability and turnover. Scholars also suggested that some job policies affect teacher turnover (Wronowski & Urick, 2019), including accountability policies that were initiated by the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act and the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Regarding job factors, some levels of accountability affect teacher retention, including practices of evaluation and assessment (Wronowski & Urick, 2019). By addressing these interconnected factors, countries worldwide can reduce teacher turnover, leading to improved educational outcomes and a more consistent learning experience for students. To enhance teacher retention, we suggest that more research needs to be conducted to recap the effect of policies on teacher turnover and retention.

6. Conclusions

In this meta-analysis, our aim was to offer a thorough overview of both past and recent findings in the study of teacher turnover. To achieve this, we created a detailed and cohesive conceptual framework that identifies both the stable aspects of existing research and the areas for more investigation. Additionally, the findings highlighted that quality of leadership, teachers’ years of experience, student body characteristics, school level, and teacher ethnicity were significant predictors of teacher turnover. Moreover, our analysis sheds light on the evolving teacher turnover research on personal factors such as teacher wellbeing, self-efficacy, and commitment. Furthermore, the amount of research exploring the relationship between quality of school leadership and teacher turnover has increased. Last, the meta-analysis shows that more scholarly attention needs to be paid to policy and accountability as teacher turnover external factors.

7. Study Limitation

The studies that discussed the role of policies or professional development on teacher turnover issues were more qualitative, so we had limitations to include these factors in our study. Since we had to use the databases available to us, we might not have access to all databases and some of the articles might not be included. We intended to include global research in our study, but there were few studies from contexts other than the United States. However, a review of studies from contexts other than America highlighted the need for conducting more research regarding teachers’ exhaustion, wellbeing, and personal accomplishments. For a few factors, most of the measurements were correlation analysis and we had to convert them into odd ratios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.F.; methodology, Z.F.; software, Z.F.; validation, Z.F.; formal analysis, Z.F.; investigation, Z.F.; resources, Z.F.; data curation, Z.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.F.; writing—review and editing, Z.F. and R.V.; visualization, Z.F.; supervision, Z.F.; project administration, Z.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request for replication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sources of reviewed articles.

Table A1.

Sources of reviewed articles.

| Database | # From Search Results | # Reviewed |

|---|---|---|

| Academic Search Complete | 281 | 95 |

| EBSCOhost | 5 | 2 |

| EconLit | 8 | 3 |

| Education Source | 217 | 56 |

| Eric | 103 | 51 |

| Google Scholar | 12 | 6 |

| LexisNexis | 90 | 46 |

| ProQuest | 90 | 31 |

| Total | 806 | 290 |

Note. # = Number of articles.

References

- Almas, S., Chacón-Fuertes, F., & Pérez-Muñoz, A. (2020). Direct and indirect effects of transformational leadership on volunteers’ intention to remain at non-profit organizations. Psychosocial Intervention, 29(3), 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2021). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Borman, G. D., & Dowling, N. M. (2008). Teacher attrition and retention: A meta-analytic and narrative review of the research. (“Teacher Retention and Attrition: A Review of the Literature”). Review of Educational Research, 78(3), 367–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckman, D. G. (2021). The influence of principal retention and principal turnover on teacher turnover. Journal of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, 15(3), 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). The trouble with teacher turnover: How teacher attrition affects students and schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27(36). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J. (2023). Teacher wellbeing and turnover intentions: Investigating the roles of job resources and job demands. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(3), 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, J. L., & Tuttle, J. M. (1986). Employee turnover: A meta-analysis and review with implications for research. Academy of Management Review, 11(1), 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, F. C., Viano, S. L., & Fisher, B. W. (2019). Teacher victimization, turnover, and contextual factors promoting resilience. Journal of School Violence, 18(1), 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L. (1984). Beyond the commission reports. The coming crisis in teaching. The Rand Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq, M., Watt, H. M., & Richardson, P. W. (2022). Profiles of teachers’ striving and wellbeing: Evolution and relations with context factors, retention, and professional engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(3), 637–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derges, B. (2024). Understanding the factors related to teacher recruitment and retention in rural schools of central Illinois [Ph.D. dissertation, Western Illinois University]. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, W. (2024). Persistence despite structural barriers: Investigating work environments for Black and Latinx teachers in urban and suburban schools. Urban Education, 59(4), 1159–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfers, A. M., Plecki, M. L., Kim, Y. W., & Bei, N. (2022). How retention and mobility rates differ for teachers of color. Teachers and Teaching, 28(6), 724–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelke, N. F. (2023). The impact of teacher leadership and peer collaboration on middle school teacher retention [Ph.D. dissertation, Fordham University]. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhaber, D., & Theobald, R. (2022). Teacher attrition and mobility over time. Educational Researcher, 51(3), 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. A., & Brantlinger, A. M. (2022). Demography as destiny: Explaining the turnover of alternatively certified mathematics teachers in hard-to-staff schools. Teachers College Record, 124(4), 35–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, C. M., Santibanez, L., & Daley, G. A. (2006). Teacher recruitment and retention: A review of the recent empirical literature. Review of Educational Research, 76(2), 173–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, T. M., McRae, P. A., & Edge-Partington, M. (2023). Factors influencing beginning teacher retention during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from one Canadian province. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 4, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, K. P. (2024). Understanding the relationship among school conditions, job Satisfaction, and teacher intention to stay in charter schools versus traditional public schools [Ph.D. dissertation, The Florida State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Guthery, S., & Bailes, L. P. (2022). Patterns of teacher attrition by preparation pathway and initial school type. Educational Policy, 36(2), 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D. N., & Adams, S. J. (2007). Understanding the level and causes of teacher turnover: A comparison with other professions. Economics of Education Review, 26(3), 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, S., Garman-McClaine, B., & Carlock, K. (2022). Special education for students with autism during the COVID-19 pandemic: Each day brings new challenges. Autism, 26(4), 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, R. M. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: An organizational analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 499–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, R. M., May, H., & Collins, G. (2019). Recruitment, employment, retention, and the minority teacher shortage. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27(37), 37–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Presley, J. B. (2023). How effective administrative leadership impacts new teacher retention in matters surrounding student discipline [Ph.D. dissertation, Trident University International]. [Google Scholar]

- Kafumbu, F. T. (2019). Job satisfaction and teacher turnover intentions in Malawi: A quantitative assessment. International Journal of Educational Reform, 28(2), 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Towards an understanding of teacher attrition: A meta-analysis of burnout, job satisfaction, and teachers’ intentions to quit. Teaching and Teacher Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais-Opperman, V., Rothmann, S. I., & van Eeden, C. (2021). Stress, flourishing and intention to leave of teachers: Does coping type matter? SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 47(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo-Wilson, E., Li, T., Fusco, N., Dickersin, K., & MUDS Investigators. (2018). Practical guidance for using multiple data sources in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (with examples from the MUDS study). Research Synthesis Methods, 9(1), 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, J. W., & Swanson, P. (2024). The impact of teacher empowerment on burnout and intent to quit in high school world language teachers. NECTFL Review, 92, 103–127. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G. J. (2019). Teacher retention in a rural east Texas school district. School Leadership Review, 15(1), Art 14. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, B., Saw, G., & McCluskey, J. (2020). Teacher victimization and turnover: Focusing on different types and multiple victimization. Journal of School Violence, 19(3), 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, C. M. (2024). The influence of principal leadership style on teacher retention [Ph.D. dissertation, Saint Leo University International]. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. D., Anglum, J. C., & Crouch, M. (2023). The effects of school finance reforms on teacher salary and turnover: Evidence from national data. AERA Open, 9, 23328584231174447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. D., Pham, L. D., Crouch, M., & Springer, M. G. (2020). The correlates of teacher turnover: An updated and expanded meta-analysis of the literature. Educational Research Review, 31, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. D., Pham, L., Springer, M. G., & Crouch, M. (2019). The factors of teacher attrition and retention: An updated and expanded meta-analysis of the literature. Annenberg Institute at Brown University, 19–149. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. D., & Springer, M. G. (2023). A conceptual framework of teacher turnover: A systematic review of the empirical international literature and insights from the employee turnover literature. Educational Review, 75(5), 993–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räsänen, K., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., & Väisänen, P. (2020). Why leave the teaching profession? A longitudinal approach to the prevalence and persistence of teacher turnover intentions. Social Psychology of Education, 23, 837–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S., & Jinnai, Y. (2021). Effects of monetary incentives on teacher turnover: A longitudinal analysis. Public Personnel Management, 50(2), 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, B. H., Morris, R., Gorard, S., & El Soufi, N. (2020). What works in attracting and keeping teachers in challenging schools and areas? Oxford Review of Education, 46(6), 678–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S., & Yildirim, I. (2022). A tutorial on how to conduct meta-analysis with IBM SPSS statistics. Psych, 4(4), 640–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomonson, J. K., Still, S. M., Maxwell, L. D., & Barrowclough, M. J. (2022). Exploring relationships between career retention factors and personal and professional characteristics of Illinois agriculture teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 63(2), 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, W. A., & Carriere, D. (2021). Special education funding and teacher turnover. Education Economics, 29(5), 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taie, S., & Lewis, L. (2023). Teacher attrition and mobility. Results from the 2021–22 Teacher Follow-up Survey to the National Teacher and Principal Survey (NCES 2024-039). U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2024039 (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Vincent, M. K., Holliman, A. J., & Waldeck, D. (2023). Adaptability and social support: Examining links with engagement, burnout, and wellbeing among expat teachers. Education Sciences, 14(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronowski, M. L., & Urick, A. (2019). Examining the relationship of teacher perception of accountability and assessment policies on teacher turnover during NCLB. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27(86). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Q., Wang, X., & Song, H. (2023). The relationship between principals’ instructional leadership and teacher retention in the undeveloped regions of central and western China: The chain-mediating role of stress and affective commitment. Behavioral Sciences, 13(9), 738–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).