Abstract

Successful Education Actions (SEAs) have proven to be key to generating opportunities for vulnerable groups. Building a sustainable future requires ensuring inclusive education that addresses inequalities and fosters social cohesion, aspects that SEAs promote by addressing educational and occupational inclusion. Recent studies underline the effects of SEAs on education and social cohesion. However, their impact on employability development has been insufficiently explored. Therefore, this study presents a systematic review that explores how SEAs contribute to the development of transversal competences that improve the employability of people in vulnerable situations, impacting on three dimensions: individual characteristics, personal circumstances, and contextual factors. PRISMA2020 methodology was used, and 30 empirical articles were analysed. After analysis, the results show that the high social and educational expectations, participation, quality relationships, community engagement, and co-creation promoted by SEAs have a significant impact on the employability of participants. These factors can contribute to more sustainable cities by fostering inclusive and lasting employability. The study systematises the positive effects of SEAs on employability and proposes optimal educational strategies that facilitate informed decisions for managers and policy makers.

1. Introduction

Building a sustainable future has led the United Nations (UN) to lead a global effort to ensure that no one is left behind due to inferiority or discrimination. It involves building sustainable cities that focus on meeting the needs of their inhabitants by, among other things, securing employment and being able to participate actively in productive and social dynamics, promoting shared prosperity and stability. Spain is a multicultural country characterised by diversity, intensified in recent decades due to the increase in migratory flows. This reality is especially reflected in the classroom, where the coexistence of multiple cultures generates both challenges and opportunities for the educational system. Social inequality and the vulnerability of certain groups are of particular concern. On the one hand, foreign students, who represent 11% of the student body, present significant barriers to linguistic and cultural integration. This group is overrepresented in programmes such as Basic Vocational Training and has a low presence in the Baccalaureate, showing structural inequalities in access and academic progression (Mahía & Medina, 2022). On the other hand, around 40% of Roma students leave school at the age of 16, a figure much higher than the national average of 13.3%. This group also suffers educational segregation and a lack of continuity in post-compulsory studies, perpetuating their social exclusion (Fundación Secretariado Gitano, 2023). These inequalities in the educational sphere have a direct impact on access to employment. Educational inequalities directly affect employment opportunities, influencing the living and working conditions that shape a community’s quality of life.

The better the conditions in which a community lives and works, the greater the impact on the quality of life of its members. However, ensuring these conditions is impossible without inclusive learning that combats inequalities (ONU, n.d.). In this sense, Successful Education Actions (SEAs) have proven successful in educational inclusion, especially in vulnerable populations. Recent studies highlight the impacts of SEA on training, social cohesion, and the construction of an active citizenry capable of participating in the transformation of their environment (see, e.g., Morlà-Folch et al., 2022; Natividad-Sancho et al., 2024; Ramírez & Marín, 2022; Soriano et al., 2022). However, the impact of SEAs on employability development has not been explored. In this sense, our study carries out a documentary analysis of papers. The aim of the study was to analyse the impact of SEAs on the employability of vulnerable working-age groups. A transformative education enhances people’s preparation for the world of work. It reduces structural inequalities by generating participatory dynamics that enhance collective well-being through the involvement of the entire educational community. Ensuring access to equitable opportunities and effective participation and learning spaces for all citizens, regardless of age and social background, builds a path to shared prosperity that connects education and employment with sustainable development goals.

1.1. Walking Towards Sustainability: Challenges and Progress in Education for the Employability of Vulnerable Groups

The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development underlines equality as a fundamental pillar for building sustainable societies, highlighting the need for inclusive, quality education that enables all people to access new opportunities throughout their lives (ONU, n.d.). Within this framework, one of the drivers of social equality, quality, and individual progress is the promotion of employability and the attainment of employment (Rodrigo, 2018). Its importance drives a multitude of labour, social, and educational policies aimed at increasing the employability of citizens, with a priority focus on supporting the most vulnerable groups (e.g., ethnic minorities) (Ministerio de Trabajo y Economía Social, 2021). However, despite the importance of this phenomenon, neoliberalism attributes the responsibility of being employable to the individual (Fugate et al., 2004; Llinares et al., 2016), reducing the concept of employability to the individual’s capacity to take advantage of the education and training opportunities available to him or her to access and remain in the labour market (International Labour Organization [OIL], 2004). While the ILO urges governments to improve such opportunities, most interventions aimed at increasing employability are oriented towards the adaptive training (11) of personal skills to facilitate access to employment (Díaz & López, 2021; Jurado & Olmos, 2014; Observatorio de las Ocupaciones, 2023). In this way, the employability debate is reduced to technical questions of individual efficiency that prioritise rapid advances in insertion (Bonvin & Orton, 2009) with relatively limited effects on the achievement of sustainability for those furthest away from the labour market (Fuertes et al., 2021; Lindsay et al., 2019).

However, the concept of employability has been broadened and enriched by several studies that highlight the relevance of external factors and personal circumstances (e.g., changing and temporary labour market demands, family responsibilities, housing availability or social support) (Hillage & Pollard, 1998; McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005; González-Navarro et al., 2023). Although still in the minority, interventions targeting vulnerable populations are emerging that broaden their scope beyond the individual and adaptive and also address situational and contextual factors, adopting relational perspectives that give a central role to community interactions (Cottam, 2011, 2018; Pearson et al., 2023). Some of these initiatives are based on Sen’s (2000) capabilities approach. From this approach, they promote the whole person’s well-being and favour a more sustainable employability that aligns with personal realities and has more significant transformative potential. From this holistic approach, the Bioecological Model of Employability is proposed (Llinares et al., 2016, 2020).

The Bioecological Model defines employability as a social construct that is linked to the ability to acquire and maintain a job. This capacity is generated from the reciprocal interaction between the person, understood as an active and biopsychological human organism in development, and their immediate external environment, composed of people, objects, and symbols. From this perspective, employability is approached holistically by considering its three dimensions: individual characteristics, personal circumstances, and contextual factors. Thus, the competencies that make up employability include perseverance, stress tolerance, work readiness, academic background, learning to learn, time and task management, initiative, performance appraisal, autonomy, self-esteem, self-care, social and technical skills, work experience, flexibility, and the ability to work in a team. This holistic approach emphasises that employability depends not only on individual qualities but also on the opportunities and conditions generated by the social and employment context.

The ideas of Cottam (2011), developed in terms of ‘relational employability’ by Pearson et al. (2023), complement this framework by emphasising the crucial role of human relationships and shared values in personal and community well-being and development. This proposal argues that overcoming poverty and exclusion goes beyond providing resources or employment. It involves creating environments where human relationships and shared values are fundamental to personal and community progress. It also calls for strategies that move away from a focus solely on work-first activation and welfare conditionality, which often fail to adequately address the structural and personal barriers faced by vulnerable groups. Instead, it proposes a rethinking of the relationship between employability services and individuals, prioritising the co-creation and personalisation of interventions. This alternative model seeks to empower participants not only in access to employment but also in broader dimensions such as mental well-being (personal and family), relationship building, people’s active contribution to their communities, and strengthening their capacities. It highlights the positive impact of a socially connected life, where people feel respected, supported, and empowered to contribute to their environment and reach their full potential. This is achieved through a commitment to generating meaningful learning opportunities and jobs aligned with people’s values and motivations. It also recognises the importance of mutually supportive relationships as a key source of resilience. These relationships are essential for overcoming situations of exclusion or vulnerability while strengthening individuals and communities and fostering more substantial and equitable social cohesion. Therefore, a sustainable education should prepare people for a dynamic labour market while fostering practises and values that promote holistic well-being and social cohesion through the development of meaningful social relationships. This approach not only supports personal development but also enhances employability by fostering the development of transversal competencies that are essential tools for navigating diverse environments and addressing complex challenges in the workplace.

1.2. Successful Education Actions: Education for Employability and Sustainability

SEAs are defined as evidence-based interventions that have demonstrated their ability to improve school success and foster social cohesion in the contexts where they are implemented. These actions, identified by the European research project INCLUD-ED (2006–2011), demonstrated significant success in schools with and without disadvantaged multicultural contexts in 14 European countries (R. Flecha, 2015). Their impact goes beyond the academic sphere, fostering inclusive and equitable dialogical interactions involving the whole community (families, teachers, students, volunteers and other social actors) in various socio-educational activities and spaces within the community. They promote a collective commitment oriented towards high educational and social expectations to positively transform the environment (Díez et al., 2011; Morlà-Folch et al., 2022; Racionero & Padrós, 2010; Valls-Carol et al., 2014).

Types of SEAs include community educational participation, interactive groups (IG), dialogic discussion groups (DG), extended learning times, a dialogic model of conflict prevention and resolution (DMCPR), family education, and dialogic pedagogical training (Morlà-Folch et al., 2022). As has been demonstrated in numerous research studies, their implementation is successful. Their impact has been widely recognised and documented in recent research (e.g., Domínguez, 2018; Salceda et al., 2022 in childhood and adolescence). Moreover, the success of the dialogical foundations on which SEAs are based has been documented since their origin in the adult community setting. Studies in this context highlight their impact on instrumental learning, the creation and strengthening of social relationships and solidarity, and the promotion of community participation that achieves emancipatory outcomes (see, e.g., Fontes de Olivera et al., 2024; Gómez-Cuevas & Valls-Carol, 2022; Tellado, 2017), generating a deep sense of usefulness that fosters greater self-esteem and personal well-being (see Cantero et al., 2018).

These properties of SEAs, aimed at overcoming inequalities and social justice (R. Flecha & Villarejo, 2015), applied to the field of employability, would be aligned with socio-educational interventions focused on individual characteristics which, as indicated in Llinares et al. (2020), are the most common and widely valued from a technical perspective oriented towards labour market insertion, but also with relational approaches attentive to circumstantial and contextual factors with a notable potential for social transformation and community sustainability (Cottam, 2011, 2018; Pearson et al., 2023).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design, Protocol, and Registry

The systematic review used the PRISMA 2020 method (Page et al., 2021). In accordance with the objective of the study, the following research question was posed: Does the impact of SEAs encompass the three main dimensions that influence employability (individual, circumstantial, and contextual factors), thus contributing to the reduction in social and labour inequalities through a sustainable intervention? For this purpose, the PICO tool was used, complemented with the SPIDER model, as it is qualitative research (Cooke et al., 2012). The protocol was uploaded and registered in Open Science Framework (OSF).

2.2. Search Strategy and Information Sources

A literature search was conducted in October 2024 and at the end of December 2024 in the following databases: Web of Science (WOS), Scopus, Education Resources Information centre (ERIC), Scielo, EBSCO host, Latindex, and Dialnet.

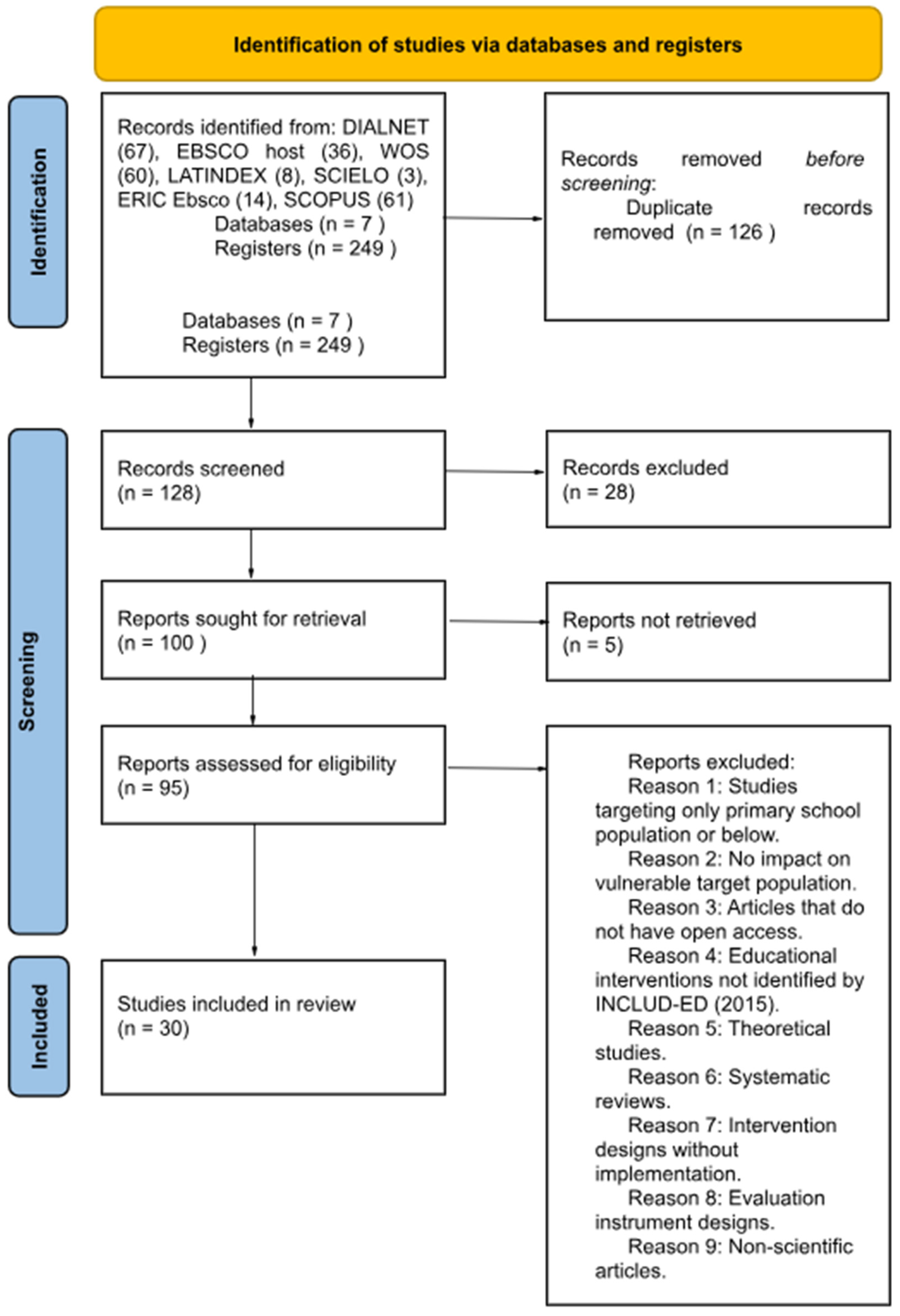

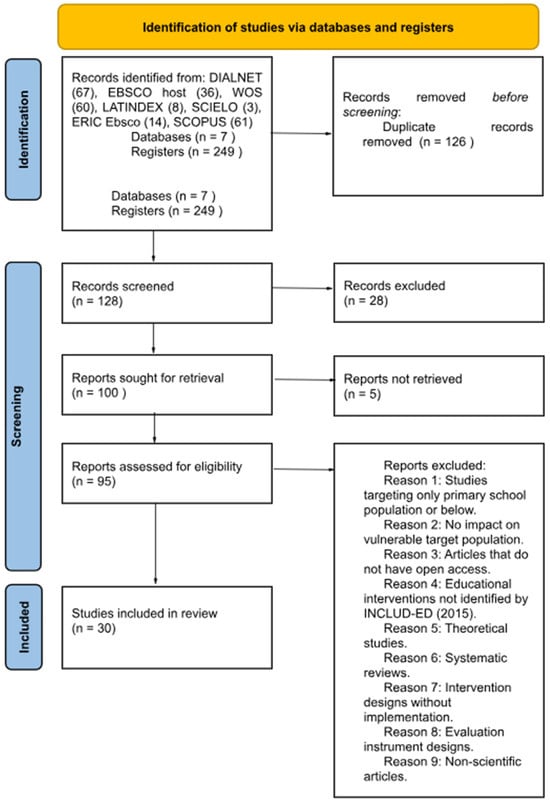

The search equation was ‘Actuaciones Educativas de Éxito’, ‘Actuación Educativa de Éxito’, ‘Successful Educational Actions’, and ‘Successful Educational Action’. Quotation marks were used to ensure that the results matched the term exactly. The search was conducted in English and Spanish, singular and plural. First, the library services of the Universitat de València suggested the following search equation: (successful OR effective OR evidence-based) AND (education* OR school*) AND (action* OR practice* OR intervention* OR strateg*). We searched the WOS database with that search equation and the results obtained in title were 3117 results. These results were not very restrictive and did not agree, for the most part, with the objective of the study. Therefore, in a second step, the search equation was adjusted to that mentioned above. Two of the authors independently searched the databases, yielding a total of 249 records. After eliminating duplicates, we obtained the first sample of 128 publications. Subsequently, the full texts of 95 articles were downloaded, thus initiating a first round of reading aimed at identifying those empirical studies that specified both the research group and the research context. As a result, some additional records were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 30 articles that were selected for in-depth content analysis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and selection process.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection Process

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined. To be included, the articles had to meet the following criteria: report on the impact of SEAs (Criteria 1) on people of working age (Criteria 2), which also included studies with secondary school students, whose age in Spain ranges from 12 to 16 years, being from 16 years of age when an adolescent can work; be exclusively empirical studies (Criteria 3); and address vulnerable groups and contexts (Criteria 4). In addition, we included studies whose abstract evidenced a possible impact on young people and adults participating as family members and/or volunteers in SEAs at any stage of schooling. The selection process of the studies involved three researchers, the authors of the research, who independently selected the articles. The selection of articles was consensual when all three judges agreed, and discrepancies were resolved through a dialogue between two researchers. Each explained her interpretation of the criteria until an agreement was reached. In disagreement, the title and abstract were read together, and the criteria were applied jointly to reach a solution. Then, to analyse the quality of the evidence, we used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2024) method.

2.4. Process of Data Extraction and Data Analysis

A content analysis was conducted to analyse the articles included in the search. This approach was used to identify thematic patterns and to classify the contents into representative categories. The categorisation system designed was based on essential principles, for example, completeness, mutual exclusion, consistency, relevance, objectivity, fidelity, replicability, and productivity (Fox, 1981; Krippendorff, 1980). In the context of qualitative methodology and considering the fundamental role of the researcher in the analysis of the results, emphasis was placed on the identification and differentiation of themes, which facilitated the organisation of the information into categories. To this end, a hierarchical structure was established that distinguished between general categories and specific subcategories, following an inductive coding approach.

The development of the codebook was carried out using a hybrid approach, avoiding the use of pre-coding before data collection. It allowed codes to emerge directly from the collected material, which aligns with Cisterna’s recommendations (Cisterna, 2005). This procedure was aligned with the guidelines proposed by Anguera (Anguera, 2003), starting with a coding system based on SEAs types, the Bioecological Model of Employability (Llinares et al., 2016, 2020), and Cottam’s (2011, 2018) contributions to relational well-being, all following a review of the results obtained. Additionally, codes derived from other themes identified in the process were incorporated (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). Their credibility and methodological rigour characterised the results obtained.

The information collected was classified and coded into three main categories (Individual competencies, Personal Circumstances, and Contextual Factors) and 25 subcategories, facilitating a clear and detailed structuring of the data (Table 1). From the outset, an Excel file was created to record the studies found. Duplicate studies were eliminated, and the literature was screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two investigators independently analysed the data from each paper. If there were discrepancies, these were analysed together until they reached agreement.

Table 1.

Categories and sub-categories indicating impact on employability.

3. Results

The influence of SEAs on the development of the employability of vulnerable people of working age was analysed in the 30 articles included in this study. According to the objective, the following research question was posed: Does the impact of SEAs cover the three main dimensions that influence employability (individual, circumstantial, and contextual factors), thus contributing to the reduction in social and labour inequalities through a sustainable intervention? Table 2 presents the main characteristics of the studies included in this search. To structure the results of the study, the categorization detailed in Table 1 was used, following the Bioecologic Model of Employability (Llinares et al., 2016, 2020) and Cottam’s contributions (Cottam, 2011, 2018) and relational well-being: (1) individual competencies, (2) personal circumstances, and (3) contextual factors. The first category, individual competencies, covers those indicators related to attitudinal or aptitudinal variables that are directly linked to the labour competencies necessary for employability. Secondly, the category of personal circumstances includes socio-family aspects that influence individual factors and determine, to a large extent, a person’s ability to integrate into the labour market. Finally, contextual factors include external indicators such as labour market conditions in a specific context and the dimensions of the macrosystem that affect both the attainment and maintenance of employment. In the presentation of the results, we begin with an analysis of each category through a synthesis of the findings obtained in each one and then proceed to describe them in detail.

Table 2.

Summary of the study characteristics.

3.1. SEAs and Their Impact on Individual Factors

Regarding the first theme, which dealt with the analysis of the improvement of academic trajectories and skills for employment, it should be noted that it was developed in all the articles included in this study. The results showed that SEAs have a key role in training vulnerable working-age groups since, in addition to reinforcing academic training, they promote the development of skills for access to employment. The aspects most-highlighted in the studies were academic training, perseverance, development of social skills, self-esteem, teamwork, initiative, and autonomy.

The subcategory ‘academic training’, widely recognised as a fundamental pillar for developing employability, takes on an even more relevant role in contexts of vulnerability. SEAs impacted this area by radically involving families and the community in education. They fostered dialogic interactions and collective support, transforming students’ academic and career aspirations from vulnerable backgrounds. A prominent example was the case of Roma students in the final year of secondary school, where community and family involvement and support were key to strengthening their confidence and opening previously unattainable academic horizons: ‘The support students received from their families helped them to have the confidence and aspirations to think about plans that included unprecedented academic trajectories’. These experiences led to profound changes in the perception of what is possible, as expressed by one student: ‘I see myself as very capable of getting to university… thanks to the support, above all’. In addition, the SEAs made visible and included university references in the educational spaces that shared cultural identity, becoming transformational models for their communities and promoting continuity in the studies of their young people (Natividad-Sancho et al., 2024, pp. 27, 30). This contact also strengthened academic willingness and readiness to work and fostered a greater ‘valuing of performance’ attitude reflecting employability.

In the case of migrant groups, IGs were shown to speed up the acquisition of the host country’s language, favouring the overcoming of key educational stages for access to university (Valero et al., 2018). In this sense, DLGs were also particularly useful, as migrant women reported: ‘If there is just one word we do not understand, we talk a lot about this word, we go round and round, and this is very important. I have been one year, but as if I had been 5 years’ (Garcia-Yeste et al., 2017, p. 104).

Among the various SEAs, family training occupied a strategic place in improving employability, as it allowed families, together with professionals, to identify specific training needs, offer resources for their development, and guarantee their access to the exact locations where their children also study and at times compatible with family dynamics. These trainings ranged from basic literacy skills to more specific content, such as preparation for driving licences and promoting collaboration with local entities to ensure their viability (Odóñez & Rodríguez-Gallego, 2018). Vulnerable families who participated in these initiatives highlighted their impacts on training: ‘I always thought about dropping out of school… illness in the family, work, problems… But I thought about the [interactive] groups, and I came. I did not miss classes, and now I will graduate’ (Rodrígues & Marini, 2018, p. 10).

The subcategory of ‘perseverance’ has also been highlighted as a key indicator of employability. Creating spaces and interactions generated by SEAs focused on support and solidarity among peers, family members, community referents, professionals, and the rest of the community was presented as a key element to foster the commitment and effort needed to overcome obstacles and achieve joint goals. Through the community’s active participation, the influence of role models with higher education who share the same cultural identity motivated us to persevere in the academic path: ‘They gave us to understand that with effort, we can achieve it… You can still decide what to do and how you want to do it.’ ‘[…] I doubted whether to continue studying, but I heard that and said, I want to continue studying’ (Roma students in Natividad-Sancho et al., 2024, pp. 26, 29). Collaboration, high expectations, and family education were elements that reinforced perseverance: ‘What I want is for them to study, to go to high school, to go to university and to continue studying, and I will do everything I can to make it happen’ (Mother in a school located in a high-poverty area, in (Garcia-Yeste et al., 2018b, p. 8).

The SEAs had a key role in the development of ‘stress tolerance’, another key employability skill, by fostering self-control, tolerance, emotional management, and effective conflict resolution. These actions created a learning climate in which students, regardless of their cultural background, were able to strengthen their relationships and overcome stereotypes. One adolescent migrant girl noted: ‘Through IGs, students learn from their peers from other cultures and together they create a positive, equitable and non-stereotypical climate, improving relationships among them’ (Valero et al., 2018, p. 794). An adolescent girl in institutional care described how these dynamics (DLG) transformed her environment and behaviour ‘Before, for example, if you said something to me and I did not like it… I would respond badly, I would get angry, I would hit you and now… I think about it more, and I do not hit things or anything. This same student described the coexistence before the SEAs as ‘chaotic’ (Salceda et al., 2022, p. 7), highlighting the positive change towards greater group cohesion, empathy and self-control. In work situations, as was the case of a Roma mother working in a ‘School as a Learning Community’ (SLC) who applies SEAs and who is now a reference in her community, proactive conflict resolution and stress tolerance were also highlighted: ‘You just stay (outside working hours) when there is a problem, and it has not been solved. I stay to talk to the teachers or the monitors to see how we can find a solution’ (Grau del Valle et al., 2023, p. 148). This commitment to immediate conflict resolution reinforced their sense of responsibility and contributed to more effective stress management.

The review also highlighted how SEAs foster the competence of ‘learning to learn’, a crucial skill for employability that involves a disposition towards continuous learning, the ability to adapt to new contexts, and the autonomy to make informed decisions. The SEAs had a significant impact on both students and families, promoting an optimistic mindset to take advantage of educational opportunities: ‘Interview data suggested that students, volunteers and teachers all had increased their expectations of learning’ (Zubiri-Esnaola et al., 2020, p. 173), ‘After seeing that our parents have not been able to have the privilege of studying, I want to take advantage of the opportunity’ […] ‘Seeing that Roma people have given us examples… has helped us a lot to be clear about what we want to do’ (Roma pupil in her last year of secondary school, in (Natividad-Sancho et al., 2024, pp. 27–28)). The active involvement of families in their children’s education in the classroom also fostered the families’ motivation to learn and be educated (Sampé et al., 2012). Family educational support was pursued to foster an apparent change in perspective towards learning, which was internalised in the community and conveyed not only an immediate obligation but an investment for future job autonomy: ‘My father will kill me if I do not come to study. Because my father tells me: What are you doing at home without studying? What are you going to do with your life? … study,… to be someone in life is not to be an illiterate person’ (Account of a young Roma girl student about a conversation with her father, in (Girbés-Peco et al., 2015, p. 104)). The DLGs generated unprecedented motivation and results among adolescent girls in a drop-in centre: ‘Before the DLGs, the groups were not so motivated to study. Never before had all the adolescent girls in a group passed all the subjects with such good grades and expectations of going to university’ (Salceda et al., 2022, p. 8). The same result was found in the quality workshops delivered through the SEA learning time extension (Gairal-Casadó et al., 2019), where high expectations play a key role in learning to learn competence.

SEAs, based on egalitarian dialogue and social interaction, significantly impacted the development of the subcategory of ‘social skills’ such as improved communication, listening, empathy and solidarity, preparing for access to the labour market and the construction of fuller lives with greater opportunities. Studies by Gómez-González et al. (2022) found improvements in communication and a greater closeness of families to the school: ‘Legitimacy and respect for teachers is increased, and parents do not oppose or argue with the teacher’s messages […] Now they know how things work’ (p. 107). This strengthening of the link between families and school reflected the development of social skills that transcend the educational sphere, fostering attitudes such as active listening and respect for rules. The participation in DLG of Lola, a homeless woman, evidenced the ability to understand the other point of view and act accordingly: ‘The encounter makes you see things differently. You become more open to other people’s opinion […] All this has opened my mind’ (Racionero, 2015, p. 922). The communicative skills acquired through collaborative learning through SEAs were also evidenced in secondary school students in special education (Álvarez-Guerrero et al., 2021).

The results showed that the support of volunteering in classroom educational activities fosters key employability competencies reflected in the subcategories of ‘time management’ and ‘task management’, as well as greater ‘flexibility’ in the face of change. Volunteers organised the group dynamics, managed the intervention shifts, and ensured that activities were completed on time. In a study where some of the volunteers in the English IGs were composed of immigrant parents, most of them with little academic background but with a command of English due to their origin, it was highlighted that ‘The volunteer was in charge of giving instructions for the game, modelling how to play, managing the turns… asks those who understand better to help explain’ (Zubiri-Esnaola et al., 2020, p. 172). Odóñez and Rodríguez-Gallego (2018) highlighted that volunteering made up of vulnerable populations demonstrated a rapid adaptation to the demands of the educational context. Similarly, it was highlighted how, in the face of unforeseen events, workers in an SLC assumed flexible responsibilities, adapting their work and schedules according to their needs (Grau del Valle et al., 2023).

The inclusion of the community in school life had a transformative effect on the people who participated, fostering their ‘initiative and autonomy’, which led them to lead processes of change. Oro and Díez-Palomar (2018) relate:

‘At the beginning of the course, I had to urge the participants to help each other […], but after a few sessions, they were already standing up for themselves as soon as they saw that one of their classmates was having difficulties […] Sharing and learning around IG from a practical and theoretical level has empowered the same participants who have led the SEAs in their classes, leading the change process themselves’.(p. 60, 68)

This leadership also extended to collective decision-making in spaces such as the mixed commissions (within the DMPRC), where key issues are discussed and decided upon, as was the case with the implementation of new educational stages in a neighbourhood with deep social inequality: ‘The educational participation of the community in the La Paz school had led families, teachers and educational leaders to opt for the implementation of secondary education in the center’ and ‘In 2012, the importance of educational participation was again manifested through another key decision (of the community): to incorporate a school for adults in the same educational center’ (Girbés-Peco et al., 2015, p. 104). This strengthening of autonomy and initiative also manifested in even more adverse contexts. In a longitudinal study in a prison, DLGs became spaces for freedom and reflection. Through dialogue, participants could project new possibilities for their future and move forward to achieve them upon release, overcoming barriers of social exclusion, reinventing and taking control of their lives to transform their personal and social trajectories (R. Flecha et al., 2012).

The subcategory of ‘self-esteem’, recognised as a key factor for employability, was strengthened through high educational and social expectations promoted through dialogic and community actions. For example, implementing Dialogical Mathematics Gatherings strengthened participants’ self-concept, especially among those facing initial educational barriers (Díez-Palomar, 2020). Including cultural diversity in heterogeneous educational spaces also significantly fostered solidarity and mutual respect, increasing self-esteem in immigrant adolescents (Valero et al., 2018). Furthermore, the sense of belonging generated by supportive communities played a central role. In the mental health field, Zubiri-Esnaola et al. (2023) documented how patients who participated in DLG in a Spanish hospital experienced personal empowerment that allowed them to actively project themselves towards transforming their reality. Similarly, Garcia-Yeste et al. (2017) highlighted how migrant mothers from impoverished contexts who participated in DLG were able to develop both language skills and greater confidence to face everyday challenges, strengthening their identity. In addition, international experiences confirmed that educational environments based on respect and dialogue promote self-esteem while fostering learning. In a school in Brazil, with a high percentage of adults who had dropped out of school due to poverty, Vieira and Miello (2018) showed that learning in a supportive and dialogical context contributed decisively to strengthening the self-concept and confidence of their participants.

SEAs also strengthened essential ‘personal and emotional care’ skills, indispensable for accessing new job opportunities and building a dignified life. Based on participation in DLG, this factor was shown in the adult population with mental illness and the prison population. The study by Zubiri-Esnaola et al. (2023) with adults with mental illness revealed that key improvements in their rehabilitation processes were linked to their participation in DLG dialogues inspired by episodes from classical world literature (p. 876). Meanwhile, the study by R. Flecha et al. (2012) highlighted testimonies such as: ‘They provided me with an important emotional situation: feeling a little less imprisoned’ (p. 155). Among socially excluded women, the impact of SEAs also translated into a revitalization of personal and emotional care. Racionero (2015) reports the testimony of a homeless woman who describes how the DLGs transformed her routine: ‘Before I would stay at home saying to myself “I do not feel like going out of the house”, I would get depressed, and now… coming here all that disappears. I feel very good, very liberated’ (p. 924). On the other hand, in Roma communities, SEAs fostered a sense of belonging that goes hand in hand with increased self-esteem, an aspect highlighted by Grau del Valle et al. (2023). Similarly, in immigrant mothers, the DLGs generated concrete impacts on their ability to relate to health and social services, as noted by Garcia-Yeste et al. (2017):

One of the women describes how she overcame a barrier when she went to health services. Prior to her attendance at the talks, she found it very difficult to relate to professionals. Now, this situation has changed, and she can explain very well what is happening to her and her children.(p. 104)

In family training, transformations in self-care and self-perception were also evident. Garcia-Yeste et al. (2018b) narrate how one participant, initially forced to attend by social services, experienced a radical change:

Belén two years ago, came with slippers, pyjamas, and so on, little hygiene […] until she signed up for family training. We started to see a change, she was more dressed up, but above all, what we noticed was a different look—not only how her son looked at her, but also how she looked at itself now. That transformation was very striking.(p. 56)

In addition, SEAs can also significantly contribute to and accelerate the development of ‘digital competencies’, which are essential for employability in an increasingly technological world. In school dropouts and unemployed adults with little education, including Roma and migrants, participation in IGs facilitated the acquisition of digital skills more quickly and confidently, thanks to their collaborative dynamics (Pacto Mundial de las Naciones Unidas. Red Española, n.d.).

Family involvement in the school and the networks generated between teachers and families also increased the ‘work experience’ subcategory of vulnerable groups, a key factor for employability. Francisco showed a remarkable commitment to the school, and the teachers encouraged him to enrol in a formal vocational school. After graduating, the school offered him a contract as a mediator to increase the participation of the Roma community (Gómez-González et al., 2022), which allowed him to gain valuable work experience within an educational environment. Also, in a very poor neighbourhood, the active involvement of the neighbourhood in their children’s school enabled them to access academic training and, in turn, work experience. One Roma neighbour expressed:

I have been able to be what I am now, which for me (…) is a lot because through these courses I can work in the summer schools, the three summer months I always work, and I have worked three years in the school canteen here.(Girbés-Peco et al., 2015, p. 105)

The impact of SEAs, such as IGs, documented the improvement of ‘teamwork’. In immigrant secondary and high school students, Valero et al. (2018) noted that ‘IGs facilitate bonds of solidarity and mutual support among peers, thus promoting a positive climate of cooperation and coexistence’ (p. 794). According to Oro and Díez-Palomar (2018), implementing IGs allowed members from vulnerable contexts to develop teamwork skills through dynamics that promote active adulthood and social inclusion through intergenerational and intercultural dialogue, generating significant learning in group contexts. In the framework of the DMPRC, a study with students aged 14 to 16 in Colombia (Sánchez, 2018) showed how the dialogic gatherings transformed school coexistence. The students drew up pedagogical accords that were agreed upon and evaluated by themselves, significantly reducing disciplinary conflicts and strengthening collaborative work. On the other hand, Garcia-Yeste et al. (2018b) describe how family education and DLGs among vulnerable minority mothers facilitated instrumental learning and strengthened trust and mutual support between families. These interactions helped families work together, share their problems and strategies to overcome them, and foster community mentoring and peer support, increasing social cohesion and collaborative skills in school and neighbourhood communities. Similarly, Vieira and Miello (2018) highlighted that learning more egalitarian dialogue based on respect and active listening strengthened teamwork skills in vulnerable populations who dropped out of school due to poverty. This impact was also observed in secondary school students with disabilities, where Álvarez-Guerrero et al. (2021) identified improvements in attention, behaviour and ability to collaborate after implementing online DLGs. Finally, Sampé et al. (2012) and Valls-Carol et al. (2014) highlighted that the involvement of vulnerable families in schools, promoting their active participation, improved coexistence and motivated both families and the school community to work together, thus reinforcing teamwork skills.

3.2. Influence of SEAs on the Personal Circumstances Factor

Regarding the second theme, SEAs had a profound and transformative impact on participants’ circumstances (circumstantial factors), generating changes beyond improving their individual skills to increase employability. Although all the studies reported changes, half highlighted this aspect more explicitly. The studies particularly highlighted the creation of quality relationships, the establishment of friendship and support networks, and the generation of social capital, which significantly enhanced the personal and social well-being of the participants. The review also identified that these experiences fostered a culture of collaboration and effort that fed back into healthy social environments, collaborative and problem-solving networks, and improved interaction with other resources.

A clear example of this impact was observed in the Moroccan women participants in DLG, who, by sharing their experiences, were able to empathise with the situation of loneliness experienced in Spain and opened new spaces for interaction, thus creating relationships that promoted a healthier and more enriching social environment (Garcia-Yeste et al., 2017). In De Botton et al.’s (2014) study, the women participating in the DLGs barely knew each other and limited themselves to a formal greeting. However, the new relationships that emerged helped strengthen true friendships over time. This type of bonding benefited these women and positively impacted people with mental health problems, who, according to Zubiri-Esnaola et al. (2023), emphasised the importance of weaving networks of relationships that help them cope with life’s difficulties. Identifying these networks becomes crucial in changing personal circumstances, moving from isolation to empowerment, where support drives change.

On the other hand, family literacy programmes, such as those described by Ocampo-Castillo et al. (2023), demonstrated how literacy improves educational skills and facilitates access to social capital. A telling example was that of Maria, who, despite never having attended school, managed to overcome her fear and shame thanks to the support of her granddaughter, with access to the programme being facilitated by taking into consideration her circumstances. This story transformed her life and allowed her to become a role model within her community, generating social capital that benefits other women. The creation of referents was also observed in programmes aimed at vulnerable families, where parents improved their skills and became role models for their children. As Dina, a mother, mentioned: ‘I am an example for them [my children]; if I have achieved it, they can achieve it’ (Garcia-Yeste et al., 2018b, p. 7). This type of social capital facilitates access to more information about the environment. It strengthens a culture of effort that can impact the community’s future, favouring their access to the labour market.

In addition, SEAs showed the fostering of a participatory culture that promotes solidarity and the creation of support networks both among participants and professionals as well as with involved entities, which facilitates access to information and better interaction with surrounding resources. In the study by Garcia-Yeste et al. (2017), one of the women participating in DLG reported overcoming barriers to accessing health services. The same study also highlighted how these experiences strengthened family relationships and bonds of solidarity. One mother expressed in another study: ‘There is good companionship, we get along well, we share everything, we help each other’ (Garcia-Yeste et al., 2018a, p. 55). At the same time, the participation promoted by SEAs in schools (decisive, evaluative, and educational participation) favoured the personal and collective promotion of the community and greater social involvement beyond the educational centres, which has a positive impact on people’s quality of life (Valls-Carol et al., 2014).

3.3. Impact of SEAs on Contextual Factors

Regarding the third and last theme, the social transformative power of SEAs offered fundamental keys for the design of social, educational, and employment policies. All the articles provided key contextual aspects for forming the employability of vulnerable groups, emphasising the creation of inclusive and supportive environments. In addition, the development of capacities that facilitate active participation in the community was highlighted (e.g., mixed commissions in Ramírez & Marín, 2022), where co-creation played an essential role in ensuring the effectiveness of these processes.

SEAs ensured a favourable context for training to be accessible to families for two fundamental reasons: they were carried out in the same school spaces where their children were studying, which allowed familiarity, proximity and easy access, and they also encouraged the co-creation of training interventions with professionals. This approach ensured that activities responded directly to the specific needs and aspirations of families and the educational community (A. Flecha, 2012; Garcia-Yeste et al., 2018a, 2018b; Gómez-González et al., 2022; Ocampo-Castillo et al., 2023; Odóñez & Rodríguez-Gallego, 2018; Sampé et al., 2012; Vieites et al., 2021).

Another important contextual factor that transcends the school setting and positively affects society at large is SEAs’ contribution to overcoming stigma and stereotypes (Valero et al., 2018). DLG empowered migrant women by breaking down stigmas of gender and ethnicity, which strengthened their social inclusion (Garcia-Yeste et al., 2017). By overcoming barriers in their communities, these women enhanced the transformative effect of these interventions.

Access to quality educational interventions is another crucial factor in transforming the social and labour context. Oro and Díez-Palomar (2018) found that even short programmes can generate and accelerate significant progress in digital skills, facilitating the labour market integration of people at risk of social exclusion. These interventions directly benefited the people who participated and strengthened community structures, promoting more sustainable environments. It was also evident in the studies by Gairal-Casadó et al. (2019), who highlighted how quality actions (scientific workshops within SEAs to extend learning times) with adolescents in institutionalised situations not only compensated for the lack of family support by providing tools for learning and improving future opportunities, but also extended their impact to strengthening vulnerable communities.

Moreover, SEAs have proven to be an effective tool to inform and guide the development of inclusive public policies. The experience of the ETPI programme (which in Portuguese refers to the Educational Territories of Priority Intervention) in Portugal (Vieites et al., 2021) illustrated how these actions can be integrated into national policies, benefiting many students and their families. This project, piloted in priority intervention territories, was expanded after successful results, demonstrating how a multidirectional dialogue between schools, researchers, governments, families and other community actors can facilitate implementing and scaling up sustainable intervention models.

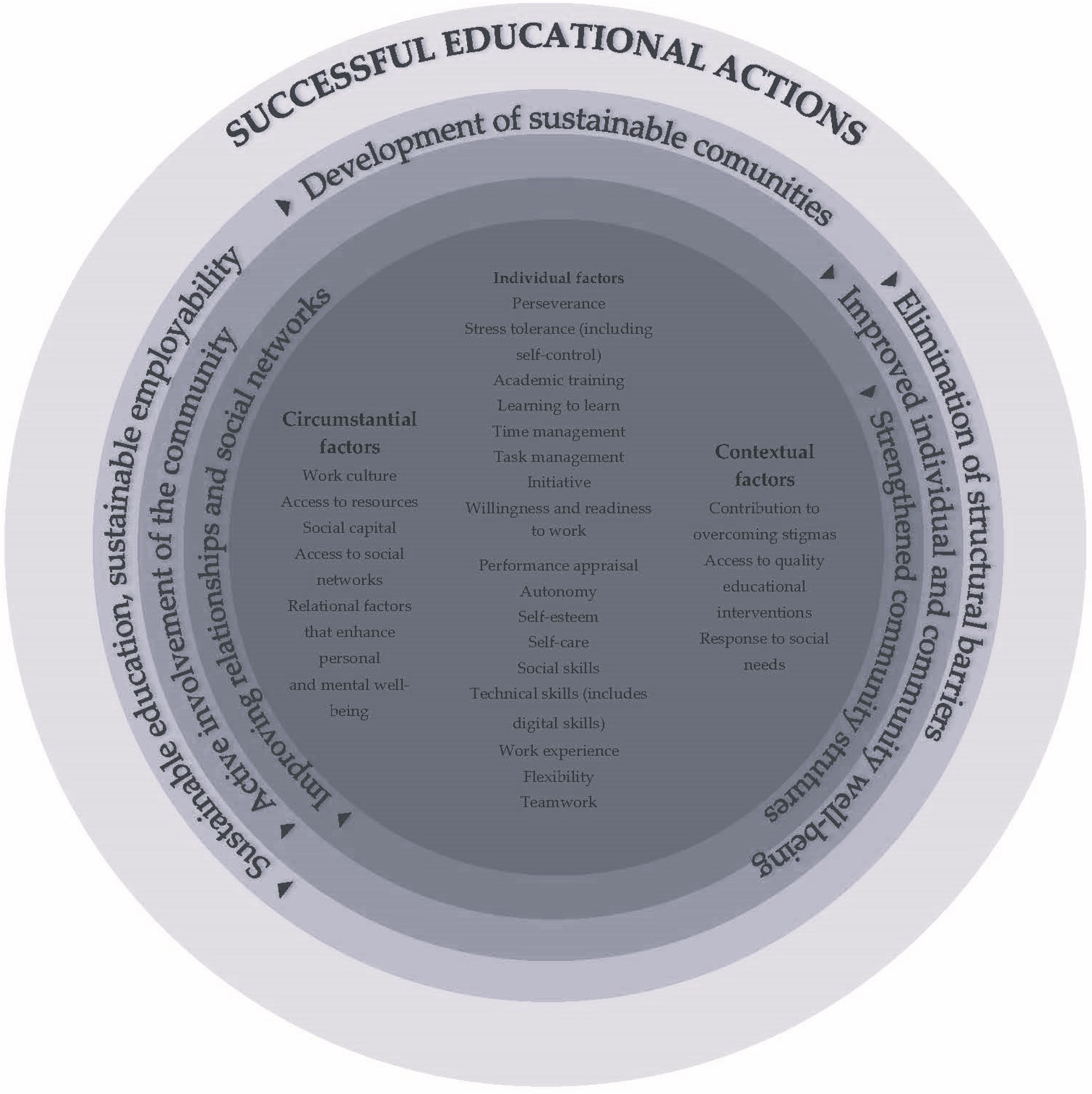

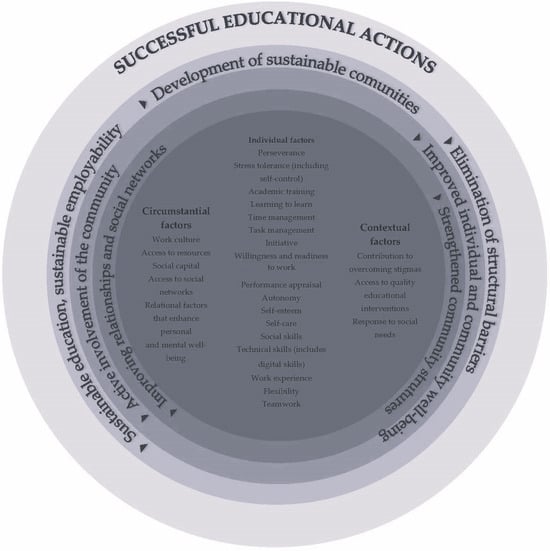

At a general level, the results showed that participation in SEAs boosted employability in their three broad dimensions: individual factors, circumstantial factors, and contextual factors, with a particular emphasis on learning of high expectations, relationships, and community participation, key elements underpinning the conceptual framework adopted to analyse this impact. The thematic analysis of these three categories is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The main findings of the study. Note: own elaboration.

The results confirm the strong interrelationship between individual, personal, and contextual factors. Their holistic approach based on SEAs contributes to the development of a more sustainable employability model for vulnerable populations, combats social and employment inequalities, and proposes a framework for more sustainable interventions.

4. Discussion

School inequalities are a global concern. They generate social and labour inequalities. In the Spanish context, characterised by its diversity and multiculturalism, these inequalities are especially evident in immigrant students, cultural minorities, those from disadvantaged backgrounds, and students with disabilities or greater educational support needs. ESAs have demonstrated their effectiveness in inclusion and in reducing inequalities in these groups. Although there are systematic reviews that have analysed their impact on primary school students (Morlà-Folch et al., 2022) and adolescents (Natividad-Sancho et al., 2024), no explicit systematisation of their contribution to the development of employability has been found. In this context, the aim of our study was to analyse the impact of SEAs on the employability of vulnerable working-age groups. Our research question was: Does the impact of ESAs encompass the three main dimensions that influence employability (individual, circumstantial, and contextual factors), thus contributing to the reduction in social and labour inequalities through a sustainable intervention?

This systematic review addressed one of the major international concerns: a sustainable, inclusive, and quality education that guarantees the demands of the labour market and reverses unemployment, poverty and social exclusion. In this way, it contributes to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 1, 3, 4, 8, and 11 (ONU, n.d.).

In general, international agencies emphasise in their agendas the need to improve the job prospects and quality of employment for disadvantaged people. To achieve this, they advocate inclusive education and training systems that respond to the diversity of needs of vulnerable groups (Pacto Mundial de las Naciones Unidas. Red Española, n.d.). These systems must identify and overcome barriers, be flexible to meet diverse individual and contextual needs, provide support services through training, promote labour rights and safety, address prejudices and social stigmas, and improve the status of these groups (OIL, n.d.). However, much remains to be done, as the goal is still relevant today. In this sense, SEAs are fundamental as they have demonstrated their capacity to generate educational and social transformations; this study analysed their role in developing transversal employability competencies individual factors. SEAs develop key transversal competencies for a changing labour market. Secondly, the results of this study underline the transformative role of SEAs in enhancing employability because they included three main factors: individual factors, circumstantial factors, and contextual factors. This impact is underpinned by sustainable education, emphasising learning with high expectations and the importance of relationships and dialogic community engagement as key elements. These dimensions underpin the conceptual framework adopted, respond to our research questions, and emerge as fundamental pillars for addressing educational and occupational inequalities. Social interaction based on reflection from egalitarian dialogue, solidarity and the establishment of quality relationships between students, families, education professionals, and the rest of the educational community are drivers of change. These interactions strengthen key competencies, mobilise resources, and build environments that transcend the limits of the school, becoming spaces for labour inclusion. Therefore, SEAs are key tools for fostering sustainability by facilitating labour market insertion, promoting more effective adaptation to social needs and market demands and, consequently, supporting long-term socio-occupational development.

From this transformative perspective, it is crucial to specify how these dynamics are linked to the employability of vulnerable groups. First, in line with previous studies that highlight academic training as a key factor and essential filter for access to employment (Formichella & London, 2013), the findings of this review highlighted that SEAs are presented as a fundamental complement within educational systems and programmes. In addition to strengthening academic training, SEAs played a crucial role in the development of other key competencies, such as perseverance, stress tolerance, self-esteem, social and technical skills, learning to learn, time and task management, willingness and readiness to work, performance appraisal, flexibility, teamwork, self-care, and work experience, competences identified in the international literature as transversal for the development of employability (González-Navarro et al., 2023). These competencies, fundamental for labour market insertion, were strengthened through dynamics that promote high academic and social expectations, egalitarian interactions, dialogue, and mutual support, allowing participants to overcome obstacles and develop a more significant commitment to their learning and professional development.

Second, the results showed that SEAs strengthened the individual factors previously highlighted and generated significant transformations in circumstantial factors, promoting stronger personal well-being. The social support networks that emerge through these actions, such as collaboration, problem-solving, safety, or friendship, are aligned with the relational well-being model proposed by Cottam (2011). This model highlights the importance of relationships in solving problems and facilitating a process of discovery and transformation, in which professional figures and support persons do not intervene directly but listen, challenge, and support this process.

According to Cottam (2018), when people receive the proper support and build meaningful connections, they acquire the necessary tools to change their personal circumstances and transform their social realities. He further emphasises that capacities must be developed locally, with relevant support (Cottam, 2011). Relationships within families, between families and the team, and with broader social connections are key to generating sustainable change. Similarly, Pearson et al. (Pearson et al., 2023) and their relational employability approach highlighted that employability depends on acquiring skills and building social and community support networks that enable individuals to make informed choices and overcome social barriers. In this sense, SEAs support coping with everyday difficulties and foster relational employability by promoting collaboration and solidarity. Participants can receive support and, at the same time, contribute to the common good, either through volunteering or by participating in collective decision-making processes, such as the joint commissions within the DMPRC. This shared approach reinforces a sense of belonging and social responsibility, building strong bonds that foster trust and quality relationships, helping to overcome situations of isolation and exclusion.

Along these lines, Waldinger and Schulz (2023) highlighted that the brain responds positively to contact with others. They noted that positive interactions signal security, reducing physical arousal and increasing well-being. Thus, social connections keep us happier and healthier and reinforce the importance of quality human relationships, such as friendship, which ensure holistic, healthy, and positive cognitive and emotional development, not only for the individual but also for humanity (Racionero-Plaza, 2017).

Following Cottam’s (2011) vision, this transformation process moves away from blame culture and towards creating new connections and networks, which, in turn, can open doors to new jobs, interests, and support. With SEAs, this process was also enriched by the visibility of positive referents, socialisation into a culture of effort, collaboration and leadership, and overcoming barriers to accessing other environmental resources, improving people’s quality of life. Therefore, this holistic approach strengthens social capital, enhances empowerment, and builds resilience, significantly impacting individuals and their families and communities, transforming them into more inclusive, supportive, and sustainable environments.

Furthermore, the results showed that contextual factors emerged as central to the transformative impact of SEAs. The distinctive creation of more inclusive and equitable environments through SEAs can serve as a guide to ensure that any inclusion-oriented policy is effective. It is essential to establish an enabling context that supports these transformative processes. SEAs have proven crucial in facilitating access to quality educational interventions, overcoming stigma and stereotypes, and promoting dynamics that transform exclusionary practises, generating more supportive, participatory, and transformative environments.

From the capabilities approach proposed by Amartya Sen (2000), creating contexts that enable these changes is essential. Without these appropriate environments, people will not only lack the possibilities to thrive, but even if they have the potential, they will not have the capabilities to achieve it. A key transformative element is a co-creation process., which facilitates the construction of responses aligned to the real needs of the social context, linking bottom-up movements (Gómez-Cuevas & Valls-Carol, 2022; Vieites et al., 2021). Lindsay et al. (2019) indicated that accompaniment strategies are more effective when co-produced with users, as they take advantage of their assets, resources, and capacities for action, responding precisely to their needs and aspirations.

In this regard, Pearson et al. (2023) highlighted that peer-based support and co-creation of pathways to employability are positively valued, foster self-efficacy, and mitigate social isolation, reinforcing the transformative impact of these interventions. This approach provides a sense of control, empowerment, and belonging, aspects that coincide with the findings of this study, highlighting the importance of relational interactions in the creation of support networks and the transformation of personal and community circumstances. SEAs promoted people’s active participation in their change and improvement processes, integrally involving families, professionals, local agents, and volunteers, consolidating participatory processes that promote inclusion and equity.

This dynamic connects with the principles of Freire’s (1997) pedagogy of the oppressed, who argues that people, by achieving ‘conscientisation’, not only recognise social inequalities but also become empowered to transform and fight against them. In this context, the principles of dialogical learning (Aubert et al., 2008) made it possible for students, volunteers, and the rest of the community to actively participate in this ‘conscientisation’ through the actions and mechanisms of collective reflection and deliberation promoted by SEAs. Spaces such as mixed commissions allow participants, together with professional figures, to analyse their circumstances critically, reflect on the structural causes of the inequalities they face, and generate joint proposals to overcome them (Ramírez & Marín, 2022). This process strengthens individual action and leadership and fosters a commitment to the common good, mobilising local resources and strengthening community networks. SEAs’ radical commitment to volunteering and collective participation generates dynamics that transform the social fabric and consolidate sustainable development in the most vulnerable communities, promoting equity and social cohesion. Finally, the sustainability of these actions lies in their capacity to transform educational and social contexts, making them an effective strategy for combating structural inequalities. Their scalability and adaptability, together with the active and distinctive participation of all the people and groups involved (Vieites et al., 2021), consolidated SEAs as a viable tool for generating changes and building a fairer and more equitable future that enhances the employability of the most vulnerable people. As opposed to traditional interventions, which tend to prioritise employment without considering circumstantial and contextual factors that affect the most vulnerable groups, SEAs focus on overcoming these structural barriers. This comprehensive approach allows people in vulnerable situations to increase their individual competencies, in terms of academic and professional training, with a view to obtaining employment, and can also be sustainable because they alleviate personal and contextual circumstances to address the inequalities that originally limited their employability.

These actions, following Pearson et al. (2023) who criticised interventions and policies that prioritise entry into employment in the process of socio-labour integration, not only benefit people individually but also strengthen relationships and social networks, as well as foster community support and decision-making structures. This enables people not only to receive support but also to play an active role in their environment, improving both their well-being and quality of life and that of their community. In this way, they actively contribute to combating inequalities and building more inclusive and sustainable communities.

The results concluded that the high social and educational expectations, quality relationships, active participation, community engagement, and co-creation promoted by SEAs generate substantial capital with a significant impact on employability. These factors foster participants’ personal and social well-being and contribute to building more sustainable cities and more inclusive and lasting employability. Moreover, as the literature shows, SEAs are transferable to different contexts (R. Flecha, 2015), making them an applicable tool for interventions that increase the employability of vulnerable working-age groups, such as socio-occupational insertion pathways.

In this sense, training in SEA for education professionals (e.g., social education, pedagogy, social work, teachers and school management) is essential to generate real changes in the lives of the most vulnerable people. Studies have already demonstrated successful outcomes with university students participating in SEAs (e.g., Amber-Montes et al., 2024; Foncillas & Laorden, 2014). These findings highlight the importance of extending this approach to future professionals who will play a key role in socio-occupational integration. It is fundamental not only to affirm that the person must be the protagonist of his or her transformation process, as opposed to conceptions of employability that reduce access to any job without considering its impact on quality of life or its meaning for those living in vulnerable situations, but also to identify the keys to achieve it. It implies that both the professional figures and the people themselves perceive and live this protagonism as a central element in the transformation process.

It is a matter of co-creating personalised itineraries and designing solutions with the essence of community support from citizens and the backing of science, hand in hand with professional figures. Based on co-creation, this approach promotes the person’s active and effective participation, reinforcing their responsibility, motivation, and commitment in their labour market insertion process.

In this context, these findings underlined the need to implement and expand these actions through public policies, consolidating SEAs as a sustainable and transformative strategy capable of redefining employability trajectories marked by social exclusion towards decent, sustainable opportunities that facilitate social mobility. Thus, this study has systematised the impact of SEAs on the development of employability of vulnerable working-age groups. However, it should be noted that this work has some limitations, which, although they do not affect the validity of the findings, open opportunities for future research. For example, a specific search was not carried out for each of the seven types of SEA, nor were the bibliographical references of the selected articles explored, a strategy that could have enriched the results by identifying additional studies (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). Furthermore, the search equations used, although well-founded, may not have covered the totality of relevant studies due to variations in titles or keywords used by different authors. Future research could address these issues by broadening the databases consulted, deepening the bibliographic references and designing specific searches by type of SEA, which would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of their impact. In addition, we have used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2024) method to analyse the quality of evidence of the articles; however, there are other methods that could also be used, for example, GRADE (Aguayo-Albasini et al., 2014). Finally, we would also like to highlight that, as a search criterion, we have used the inclusion of SEAs only identified in INCLUD-ED. Future research should consider including all articles describing SEAs, even those not identified by the INCLUD-ED project, if they meet the established criteria. This would broaden the evidence base and ensure a more comprehensive and representative analysis of the available data.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to analyse SEAs as guarantors of educational sustainability, with a focus on their impact on the development of employability of vulnerable working-age groups. The findings confirm that SEAs were found to develop key transversal competences to adapt to a dynamic and constantly changing labour market. Furthermore, SEAs were shown to have a transformative role in enhancing employability by addressing individual factors, personal circumstances, and contextual factors. Moreover, SEAs are key tools for fostering sustainability by facilitating labour market entry, promoting more effective adaptation to social needs and market demands, and consequently supporting long-term socio-occupational development. Therefore, the most significant contribution of this work is its comprehensive approach that encompasses the entire community. This holistic approach allows SEAs to be guarantors of educational sustainability. This highlights the development of more sustainable employability of the most vulnerable working-age group.

These findings highlight the importance of SEAs in moving towards inclusive, quality, and sustainable education, aligned with the development of sustainable employability. The skills and relationships promoted by SEAs foster social justice and overcoming inequalities, thus contributing to community sustainability.

From a practical perspective, it is essential to incorporate educational and socio-occupational strategies that integrate SEAs as transformative tools, ensuring relevant interventions and adequate support to improve the employability of vulnerable groups. Furthermore, education policies should prioritise relational approaches that strengthen dialogical participation and meaningful connections between students, families, education professionals, and researchers, promoting co-creation processes that provide solutions to the diversity of contexts by jointly recreating the evidence that science has already shown to have a social impact. In this way, these actions transform individual realities and enhance far-reaching social sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.R.-C., L.I.L.-I., L.G.-R. and C.G.-d.-V.; methodology, L.I.L.-I., E.R.-C., L.G.-R. and C.G.-d.-V.; validation, C.G.-d.-V., L.I.L.-I., L.G.-R. and E.R.-C.; formal analysis, C.G.-d.-V., L.I.L.-I., E.R.-C. and L.G.-R.; resources, C.G.-d.-V., E.R.-C., L.G.-R. and L.I.L.-I.; data curation, C.G.-d.-V., L.I.L.-I., E.R.-C. and L.G.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G.-d.-V., E.R.-C., L.G.-R. and L.I.L.-I.; writing—review and editing, E.R.-C., C.G.-d.-V., L.G.-R. and L.I.L.-I.; visualization, C.G.-d.-V., E.R.-C., L.G.-R. and L.I.L.-I.; supervision, L.I.L.-I., L.G.-R., C.G.-d.-V. and E.R.-C.; project administration, C.G.-d.-V., L.I.L.-I., L.G.-R. and E.R.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Universitat de València.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aguayo-Albasini, J. L., Flores-Pastor, B., & Soria-Aledo, V. (2014). Sistema GRADE: Clasificación de la calidad de la evidencia y graduación de la fuerza de la recomendación. Cirugía Española, 92(2), 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amber-Montes, D., Martínez-Valdivia, E., & Pegalajar-Palomino, M. C. (2024). Dialogic learning as a successful educational performance for sustainable development in higher education. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 4(2), 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguera, M. T. (2003). La observación. In C. Moreno (Ed.), Evaluación psicológica. Concepto, proceso y aplicación en las áreas del desarrollo y de la inteligencia (pp. 271–308). Sanz y Torres. [Google Scholar]

- Aubert, A., Flecha, A., García, C., Flecha, R., & Racionero, S. (2008). Aprendizaje dialógico en la sociedad de la información. Hipatia. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Guerrero, G., López de Aguileta, A., Racionero-Plaza, S., & Flores-Moncada, L. G.-R. (2021). Beyond the school walls: Keeping interactive learning environments alive in confinement for students in special education. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 662646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonvin, J., & Orton, M. (2009). Activation policies and organisational innovation: The added value of the capability approach. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 29(11/12), 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantero, N., Pantoja, A., & Alcaide, M. (2018). Impacto de la participación de los abuelos en una comunidad de aprendizaje. Research on Ageing and Social Policy, 6(2), 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisterna, F. (2005). Categorización y triangulación como procesos de validación del conocimiento en investigación cualitativa. Theoria, 14, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottam, H. (2011). Relational welfare. Soundings, 48, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottam, H. (2018). Radical help. Virago. [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2024). CASP checklist. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- De Botton, L., Girbés, S., Ruiz, L., & Tellado, I. (2014). Moroccan mothers’ involvement in dialogic literary gatherings in a Catalan urban primary school: Increasing educative interactions and improving learning. Improving Schools, 17(3), 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, M. J., & López, P. (2021). Ayudar activando. Agentes de empleo ante las ambivalencias de la “Ocupación Plena”. Cuadernos de Relaciones Labourales, 39(1), 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, J., Gatt, S., & Racionero, S. (2011). Placing immigrant and minority family and community members at the school’s centre: The role of community participation. European Journal of Education. Research, Development and Policy, 46(2), 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Palomar, J. (2020). Dialogic mathematics gatherings: Encouraging the other women’s critical thinking on numeracy. ZDM—Mathematics Education, 52, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, F. J. (2018). Fundamentos y características de un modelo inclusivo y de calidad educativa: Comunidades de aprendizaje. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 11(22), 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Domínguez, F. J., & Palomares, A. (2022). Tertulias Dialógicas Artísticas. Una apuesta por la inclusión y mejora de la convivencia a través de la cultura. Prisma Social: Revista De Investigación Social, 37, 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha, A. (2012). Family education improves student’s academic performance: Contributions from European research. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 2(3), 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha, R. (2015). Successful educational actions for inclusion and social Cohesion in Europe. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Flecha, R., & Villarejo, B. (2015). Pedagogía crítica: Un Acercamiento al derecho real de la educación. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social, 4(2), 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha, R., García, C., & Gómez, A. (2012). Transferencia de tertulias literarias dialógicas a instituciones penitenciarias. Revista de Educación, 360(8), 40–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foncillas, M., & Laorden, C. (2014). Aprendizaje a través del diálogo en educación social. International Journal of Sociology of Education, 3(3), 244–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes de Olivera, C., Rodrigues, R., Fernandes, A., De Lima, F., & Marini, F. (2024). Escola de pessoas adultas de la verneda e sant-martí: Sonho e ciência em educação. Revista Brasileira de Educação, 29, e290082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formichella, M. M., & London, S. (2013). Empleabilidad, educación e igualdad social. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 47, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D. J. (1981). El Proceso de investigación en educación. EUNSA. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (1997). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes, V., McQuaid, R., & Robertson, P. J. (2021). Career-first: An approach to sustainable labour market integration. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 21, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación Secretariado Gitano. (2023). La situación educativa del alumnado gitano en España. Informe ejecutivo. Fundación Secretariado Gitano. [Google Scholar]

- Gairal-Casadó, R., Gacía-Yeste, C., Novo-Molinero, M. T., & Salvadó-Belarta, Z. (2019). Out of school learning scientific workshops: Stimulating institutionalized adolescents’ educational aspirations. Children and Youth Services Review, 103, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Yeste, C., Gairal, R., & Gómez, A. (2018a). Aprendo para que tú aprendas más. Contribuyendo a la mejora del sistema educativo a través de la formación de familiares en comunidades de aprendizaje. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación al Profesorado, 32(93), 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Yeste, C., Gairal, R., & Ríos, O. (2017). Empoderamiento e inclusión social de mujeres inmigrantes a través de las tertulias literarias dialógicas. Revista Internacional de Educación Para la Justicia Social, 6(2), 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Garcia-Yeste, C., Morlà, T., & Ionescu, V. (2018b). Dreams of higher education in the mediterrani school through family education. Frontiers in Education, 3, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girbés-Peco, S., Macías-Aranda, F., & Álvarz-Cifuentes, P. (2015). De la escuela gueto a una comunidad de aprendizaje: Un estudio de caso sobre la superación de la pobreza a través de una educación de éxito. International and Multidisciplinary Journal in Social Sciences, 4(1), 88–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Navarro, P., Córdoba-Iñesta, I., Casino-García, A. M., & Llinares-Insa, L. (2023). Evaluating employability in contexts of change: Validation of a scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1150008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Cuevas, S., & Valls-Carol, R. (2022). Social impact from bottom-up movements: The case of the adult school la verneda-sant martí. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 12(3), 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-González, A., Tierno-García, J. M., & Girbés-Peco, S. (2022). “If they made it, why not me?” increasing educational expectations of Roma and Moroccan immigrant families in Spain through family education. Educational Review, 76(1), 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau del Valle, C., García-Raga, L., Barrachina-Sauri, M., & Roca-Campos, E. (2023). Estudio de caso del impacto del proyecto comunidades de aprendizaje en el aumento de la empleabilidad de la población gitana en situación de desigualdad social. International Journal of Sociology of Education, 13(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillage, J., & Pollard, E. (1998). Employability: Developing a framework for policy análisis. Department for Education and Employment. [Google Scholar]