Abstract

This scoping review provides clarity on the landscape of evidence-based and High-Leverage Practices that have been shown to be effective with students with disabilities and have the potential to meet the needs of marginalized students across lines of difference. Of 672 articles screened, 85 met eligibility criteria, including 46 studies, 11 systematic reviews, and 28 conceptual papers. Among included articles, instruction practices were the most frequently reported High-Leverage Practice category (89.4%), followed by social, emotional, and behavioral practices (37.6%), and assessment practices (25.8%). A wide variety of specific evidence-based practices were identified in the literature. Marginalized student identities represented included English language learners, students with disabilities, neurodivergent students, racially or ethnically marginalized students, students with health disabilities, and students with behavioral or emotional difficulties. Future research should consider further examining the effectiveness of different practices to inform data-driven decision-making to improve educational outcomes for marginalized students.

1. Introduction

Unequal access to quality education and the resultant achievement gaps experienced by students from marginalized groups contribute to education disparities along the lines of race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, ability, and these intersecting identities. These educational disparities can have long-lasting effects on students’ opportunities and life outcomes, such as contributing to limited access to higher education and employment opportunities, as well as perpetuating cycles of poverty and inequality (Ross et al., 2012; Cox, 2016). High-leverage practices (HLPs) and evidence-based practices (EBPs) present an opportunity to mitigate these disparities. HLPs were initially designed to be used with students with disabilities, and both HLPs and other EBPs have the potential to promote improved student outcomes, regardless of background or identity (McLeskey et al., 2017; Nelson et al., 2022; Osher et al., 2018). However, little is known about the scope and potential impact of HLPs and EBPs used in diverse classrooms and the system conditions needed for their proper implementation. The present study assesses the current knowledge base around HLPs and EBPs that have the potential to support educators, administrators, and policymakers in meeting the needs of all students in diverse and inclusive classrooms.

While research shows that teaching practices and materials that account for classroom diversity and recognize marginalized students’ lived experiences are more effective (Byrd, 2016; Foorman et al., 2016), prejudice against Black, Hispanic, Pacific Islander, Asian, and Indigenous students limits the implementation of these practices in classrooms. Racism, classism, and ableism deeply impact how the education system attempts to meet both the educational and social needs of its students (Payne, 1984). In the United States, federal laws and policies such as The Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, among others, prohibit discrimination in education based on identities such as race, class, and ability (U.S. Department of Education, 2024). While these laws are designed to ensure that all students have equal access to education and aim to create more inclusive educational environments and opportunities, in practice, major challenges remain due to deep-seated systemic biases. Consequently, disparities in the education outcomes for K-12 students of color, Indigenous students, low-income/SES students, English language learners (ELLs), and students with disabilities persist (McIntosh et al., 2014; McGrath & Elgar, 2015; Callahan, 2005; Ortiz, 2001) and can have widespread social, emotional and behavioral consequences (Owens & McLanahan, 2020; Hughes et al., 2020). Addressing disparities is a crucial step in the journey toward creating an equitable classroom in which all students can reach their potential.

The implementation of HLPs and EBPs, which embrace a variety of strategies that can promote high quality, effective teaching and equitable learning, can set the stage for minimizing disparities that stem from racism, classism, and ableism through setting high expectations, tending to students’ unique needs, and promoting positive student outcomes. HLPs comprise a framework formalized by the Council for Exceptional Children that includes assessment, instruction, and social and collaborative practices and is designed to better prepare teachers to meet the needs of diverse learners (McLeskey et al., 2017). These, as well as EBPs—broader, peer-reviewed, scientifically informed practices (Cook & Cook, 2013)—can be applied to K-12 education methods for students with marginalized identities, as both have been shown to improve the quality of education for diverse populations of students (Nelson et al., 2022). Both HLPs and EBPs apply to broader populations (McLeskey et al., 2017), as the scope of their practices aids in learning efforts for both general and special education K-12 students.

However, there is a lack of clarity around the scope of HLPs and EBPs that have the potential to help educators meet the needs of all marginalized students. The current study seeks to synthesize the knowledge of existing HLPs and EBPs for marginalized students through a scoping review. This study aims to identify and elevate practices with the greatest potential for helping both general and special educators meet the needs of all students in diverse and inclusive classrooms. Identifying such practices is critical for informing professional development priorities for in-service teachers and pre-service teacher training and assisting funders and policymakers seeking to encourage practices that will benefit all students. This study is guided by the following questions: (1) What is the extent of the research on evidence-based, High-Leverage Practices for marginalized populations?; (2) What evidence-based, High-Leverage Practices have demonstrated success in academic achievement for diverse students enrolled in the K-12 education system in the United States?; and (3) What does the identified literature say about system conditions needed to adopt the identified effective teaching practices for K-12 students?

2. Method

This scoping review used education, social science, and humanities databases to identify peer-reviewed, scholarly, and gray literature focused on HLPs and/or EBPs used with marginalized students. Marginalized students were defined as those who had racial or ethnic minority identities, were English-language learners (ELLs), had low socioeconomic status, and were students with disabilities.

2.1. Search Strategy

The literature search was conducted from May 2023 to June 2023 using the following databases and search engines: APA PsycInfo, Education Research Complete, ERIC, Gender Studies Database, LGBTQ+ Source, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, SocINDEX with Full Text, Sociological Collection, Women’s Studies International, Academic Search Complete, JSTOR, ProQuest, and Google Scholar, as well as publication repositories of research and philanthropic organizations that focus on teaching practices. Keywords were used that captured information on HLPs or EBPs (e.g., evidence-based OR evidence-informed OR teaching strateg*), marginalized student groups (e.g., black OR African American OR latine OR economically disadvantaged OR dual language learner* OR disab* OR neurodiverg* OR indigenous), and grade level (e.g., elementary OR middle school OR high school). See Supplemental Material Document S1: Example Electronic Search Strategy for an example search strategy.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Literature was included in this review if it was published in English, published in 2013 or later, described evidence-based or evidence-informed teaching practices or programs, and had a focus on K-12 marginalized students in the United States school system. Peer-reviewed literature, book chapters, evaluation reports, technical reports, white papers, non-scholarly project reports, advocacy reports, and other gray literature were included. Excluding dissertations was deemed appropriate because the significant findings from these research works were captured in published articles.

2.3. Screening and Eligibility

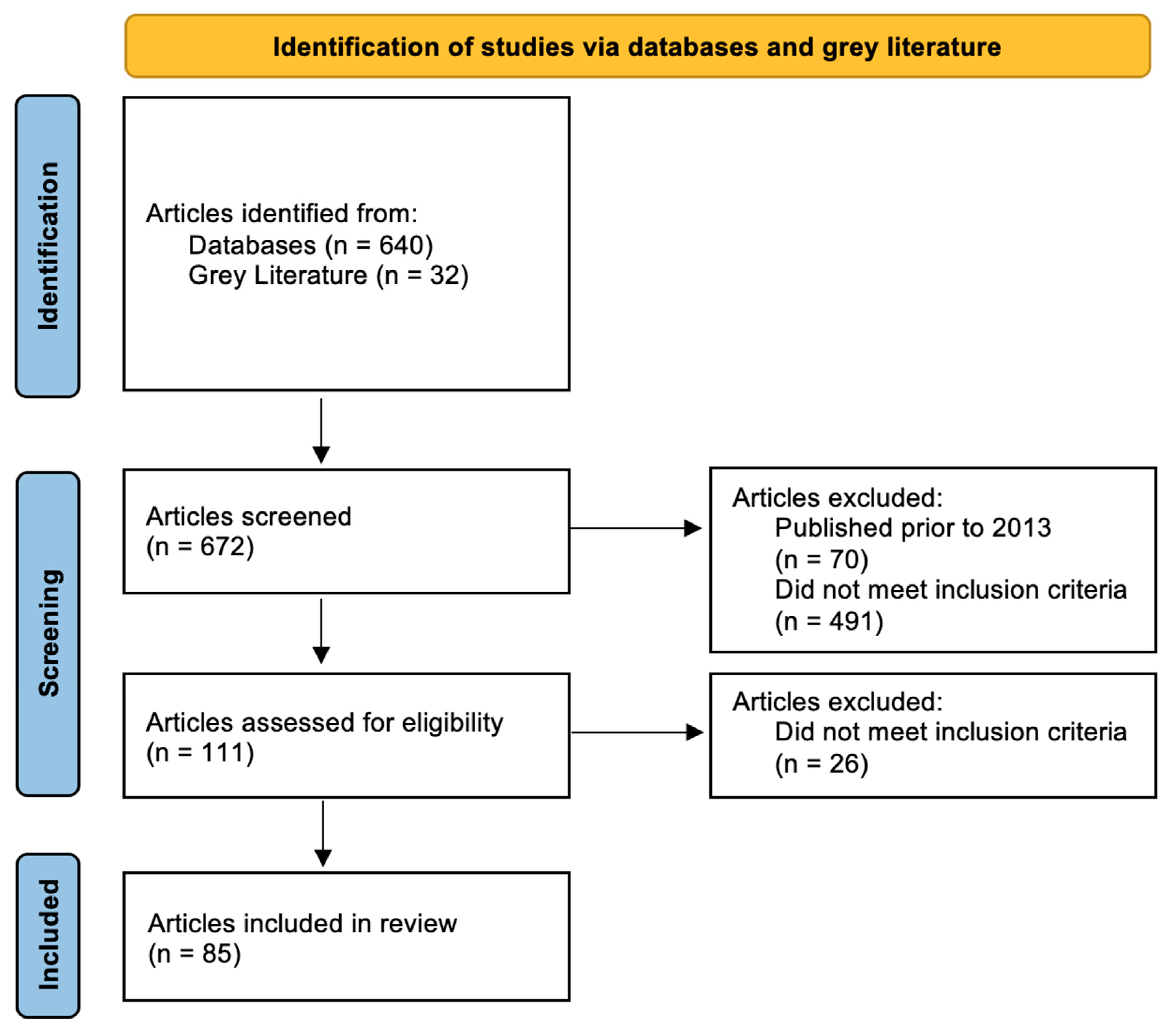

After literature deduplication, two reviewers screened the titles and abstracts for inclusion or exclusion, consulting with a third reviewer to reconcile discrepancies. Full texts were screened and reviewed for inclusion/exclusion by three authors. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram and Supplemental Material Checklist S1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist (Tricco et al., 2018).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

A data extraction form was used to collect key information from the included literature, including the paper objective, HLPs or EBPs discussed, the theory or conceptual framework, study sample/population characteristics, school age group, study methodology, outcomes of focus, and key findings, as applicable. The data extraction form was piloted by one author and revised accordingly prior to full data extraction. The information collated in the data extraction form was summarized quantitatively and thematically.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Identified Literature

Overall, 85 papers were included in the final sample; of these, 46 were research studies, 11 were systematic reviews, and 28 were non-research papers that included gray literature, such as conceptual papers and reviews.

Of the research studies, a range of marginalized student identities were represented in the study sample (see Table 1). Approximately one-third of studies (n = 15) had a majority Hispanic or Latino/a sample. Thirteen studies (28.3%) had majority White students participating in the study, followed by studies that had an even distribution of different races and ethnicities (n = 7; 15.2%), and majority African American (n = 5; 10.9%). One study sample included majority Native American English-language learner students, and one study included Indigenous Hawaiian students. Four studies did not clearly report the racial or ethnic breakdown of the student sample.

Table 1.

Summary of papers.

One-third of identified studies (n = 15) focused on students with learning disabilities or learning difficulties or were otherwise neurodivergent; three studies (6.6%) included samples of students with disabilities but did not specify the type of disability. In addition, nine studies (20.0%) focused on English language learners only; five studies (11.1%) included samples with primarily low-socioeconomic status students; four studies (8.9%) included students with behavioral or emotional difficulties; and four studies had study samples that consisted of racial minority students. In addition, nine studies (20.0%) included a study sample that consisted of students with intersecting minoritized identities (e.g., English-language learners with learning difficulties and low SES).

Almost half of studies focused on elementary students (n = 21; 45.7%), followed by middle school students (n = 13; 28.3%), high school students (n = 6; 13.0%), combined elementary and middle school students (n = 2; 4.4%), alternative school settings (n = 2; 4.4%), combined middle school and high school (n = 1; 2.2%), and K-12 (n = 1; 2.2%).

Eleven systematic review papers were identified, including three meta-analyses. The systematic reviews focused on students with intellectual and learning disabilities or difficulties, students with emotional–behavioral disorders, students with visual impairments, and ethnic and racially minoritized students across K-12. Systematic reviews examined a range of student outcomes, including math achievement, reading, literacy, and language development, and social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes.

Non-research papers included narrative reviews and other comprehensive literature reviews, conceptual papers, technical reports, descriptions of teaching practices, and instructional guidance. These papers focused on a variety of student populations. Two-thirds of non-research papers focused on K-12 students (n = 19; 67.8%), followed by middle school students (n = 4; 14.3%), high school students (n = 3; 10.7%), and elementary school students (n = 2; 7.1%). About one-fifth of non-research papers (n = 5, 17.8%) were written about teaching practices with students who were Indigenous, Hispanic/Latino/a, or Black. Three papers (10.7%) described HLPs/EBPs for BIPOC students. Two papers (7.1%) described HLPs/EBPs for Hispanic or Latino/a students. One paper (3.6%) described HLPs/EBPs for Indigenous Hawaiian students. Over half of the non-research papers were written for teaching practices with students with disabilities (n = 17, 60.7%). Among these papers, three papers (17.6%) focused on students with autism spectrum disorder. One paper (5.8%) focused on students with emotional/behavioral difficulties (see Table 1).

3.2. HLP and EBP Strategies and Programs

All reviewed papers included in the study were assigned at least one of four High-Leverage Practice (HLP) categories (McLeskey et al., 2019): (1) assessment, (2) collaboration, (3) instruction, and (4) social/emotional/behavioral practices. Table 2 provides descriptives on research studies and non-research studies separately across all HLP categories. Most papers included instructional practices, followed by social, emotional, and behavioral practices, assessment practices, and collaboration practices. There was overlap between the papers in the assessment category and papers focused on the other HLP categories. For example, several research studies examined Concrete–Representational–Abstract (CRA) approaches, which span assessment, instructional, and social, emotional, and behavioral HLP areas (Bismarck & Prosser, 2023; Flores et al., 2014; Hinton & Flores, 2019). In addition, several papers focused on Universal Design, which incorporated assessment, collaboration, instruction, and social, emotional, and behavioral HLP areas (Anderson, 2022; Domitrovich et al., 2022; Israel et al., 2014). While 18.2% of non-research papers included assessment practices, there was only one research study that focused solely on assessment practices: Kong et al. (2021), who examined the Word-Problem-Solving (WPS) intervention. See Supplementary Table S1: Evidence-Based Programs Overview for more details about alignment among EB practices and HLP categories.

Table 2.

Frequency of reported HLP categories among papers (n = 85).

3.3. Theoretical and Conceptual Foundations of HLP and EBP Programs and Strategies

Of all the papers, 32 explicitly identified a theory or conceptual framework relevant to the focus of this scoping review. There was minimal overlap in terms of theories, frameworks, and models used. For example, one research paper used the Self-Determined Learning Model, grounded in causal agency theory (Shogren et al., 2015; Shogren et al., 2018), to guide their studies on instruction and social, emotional, and behavioral practices. Two non-research papers referenced ecological systems theory (e.g., Brown & Doolittle, 2008) as it related to HLP/EBP instructional categories of collaboration, instruction, assessment, and social, emotional, and behavioral practices. Overall, several papers drew on culturally relevant teaching, culturally relevant critical theory, or other socio-cultural theories. The remaining papers each used a distinct theory.

3.4. Student Outcomes: Research Study and Systematic Review Findings

Studies and systematic reviews reporting benefits for students examined a wide range of HLPs and EBPs, covering almost 50 different EBP approaches. Table 2 illustrates the extent to which different teaching practices have been adopted and implemented in the identified literature. Of the research studies, 44 reported student outcomes across a range of academic content areas, including reading, literacy, language development (n = 18; 31.1%); math (n = 10; 21.7%); social, emotional, and behavioral (n = 10; 21.7%); science (n = 2; 4.35%); social studies (n = 1; 2.2%); two or more academic areas (n = 2; 4.4%); science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM; n = 1; 2.2%); overall academic outcomes (n = 1; 2.2%); and social, emotional, behavioral, and overall academic outcomes (n = 1; 2.2%). Most studies (n = 36; 84.1%) found that EBPs of focus—approximately 30 different EBPs—had positive or beneficial effects for all students included in the study. Two (4.5%) studies reported no detectable effect and five (11.4%) found mixed results across students. Reading, literacy, and language development (n = 15) and math (n = 15) were the most frequently examined content areas, followed by social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes (n = 9), science (n = 2), and STEM (n = 1). In addition, one study examined both overall academic outcomes and social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes. Overall, the included systematic reviews found general benefits of the HLPs and EBPs reviewed for students.

While most EBPs were only examined once in the body of literature identified, several EBPs were covered in multiple studies or reviews. The Concrete–Representational–Abstract (CRA) instructional sequence of instruction and variations in CRA were examined among students with learning disabilities or neurodivergence in four different studies. CRA approaches utilize physical and visual aids, such as concrete blocks or numbers on a board, to build understanding of abstract topics. These studies found improvement in math skills for students in high school (Bismarck & Prosser, 2023), middle school (Bouck et al., 2017), elementary school (Hinton & Flores, 2019), and in an alternative school setting (Flores et al., 2014). Three studies and one systematic review (Kuntz & Carter, 2019) discussed the value of systematic instruction for elementary, middle, and/or high school students with intellectual disabilities or neurodivergence. In systematic instruction approaches, the teacher provides consistent and ongoing positive feedback to encourage ongoing engagement and active learning. Systematic instruction was most often examined in combination with at least one other approach, including pairing it with virtual manipulatives for math (Jimenez & Besaw, 2020), combining it with mobile technology and the Read-Aloud Approach for improving reading and literacy (Mims et al., 2018), and pairing it with a task-analytic approach for science (Smith et al., 2013). Notably, five studies described culturally relevant or culture-based educational approaches that embrace the languages, values, beliefs, and experiences of students. For example, one of these studies reported on the effectiveness of culturally relevant instruction/education with the ESCOLAR Collaborative Online Learning Curriculum (Terrazas-Arellanes et al., 2017). These authors found that students with learning disabilities, English-language learners, and general education students had greater improvements in science content knowledge than control groups. The remaining studies and reviews each focused on different types of EBPs (see Table 2).

3.5. Student Outcomes: Non-Research Papers

Non-research papers also discussed a wide range of beneficial EBPs across the domains of reading, literacy, and language development, math, social, emotional, and behavioral skills, and overall academic success. Most papers described different HLP and EBP strategies and programs with little overlap. One specific strategy described by two papers was the self-regulated strategy development model of writing; these papers discussed this model in terms of applicability for K-12 students with emotional and behavioral disabilities (Cuenca-Carlino et al., 2016) and elementary students with learning difficulties (Ciullo & Mason, 2017).

Some additional HLP and EBP strategies that were discussed in multiple papers included multi-tiered and culturally relevant approaches. Liasidou (2013) examined the benefits of multi-tiered Response to Intervention (RTI) in multiple academic areas for K-12 English language learners with disabilities. Richards-Tutor et al. (2016) described the effectiveness of multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) framework for reading, literacy, and language development for English-language learners. Some discussed the benefits of a multi-tiered instructional framework for English-language learner students with and without disabilities, which includes culturally relevant pedagogy; in addition, others discussed beneficial culturally relevant approaches among culturally and racially diverse K-12 students to support the development of multiple academic areas (Aceves & Orosco, 2014; Glazewski & Ertmer, 2020; Thompson et al., 2021). See Table 2 for an overview of the extent of HLP and EBP strategies described in non-research papers.

3.6. System Conditions

Very few publications (n = 3) explicitly discussed the system conditions needed to adopt the identified teaching practices for K-12 students. The common system condition examined in all three articles was effective professional learning related to the identified practices. Professional learning examined within articles included learning the theoretical basis of the teaching practices, the development of the knowledge and skills needed to deliver the practice through didactic and applied learning activities, as well as the follow-up needed to provide support when used within classroom settings (Krawec & Montague, 2014; Ochsendorf & Taylor, 2016; Odom et al., 2014). Other system conditions examined included leadership support, including the provision of time for teacher planning and professional learning, the provision of resources and accountability for the use of the practices, coaching, the use of data to support decision-making and improvement, and the use of teacher teams to support the planning and use of the practices (e.g., Professional Learning Communities) (Ochsendorf & Taylor, 2016; Odom et al., 2014). No articles examined a coherent or comprehensive system of the enabling conditions needed to support the effective use of teaching practices.

4. Discussion

This scoping review identified the body of literature on HLPs and EBPs that have the potential to help educators meet the needs of marginalized students along the lines of race, ethnicity, income, native language, and ability. Eighty-five papers were identified that included diverse study samples or otherwise discussed students with marginalized identities. The use of a wide range of HLPs and EBPs across diverse student bodies necessitates further research to determine the most promising approaches. While our search focused on samples of students from various identities, it is worth noting that most of the studies demonstrating benefits or improvements showed positive outcomes for all students. This finding highlights the inclusive nature of these practices and their potential to benefit diverse student populations. Although the majority of evidence identified in our scoping review focuses on students with learning disabilities, it is not surprising considering that HLPs were originally designed for such students. However, this highlights the need to explore the effectiveness of different HLPs and EBPs for students with less representation in the research literature. Better understanding the potential impact of HLPs and EBPs for these students will help to determine which may be most effective for students with diverse social identities, leading to more equitable student outcomes.

In addition, there are several implications for effective implementation of HLPs and EBPs within diverse classrooms. The first of these implications is in the selection of high-quality instructional materials and resources being used as part of instruction. The adoption process of high-quality instructional materials should include an analysis of inclusion and alignment to the use of the identified HLPs and EBPs. The use of high-quality materials and resources should enable the enactment of HLPs under instruction versus impeding or creating misaligned messages to instructional staff and those supporting the delivery of instruction. A second implication can be found for the competency development activities to support the skilled use of HLPs and EBPs. Resources need to be allocated for the delivery of professional learning and coaching or necessary follow-up support to professional learning or training. Trainers or providers of professional learning should be selected for their skills and knowledge in using the identified HLPs and EBPs, as well as their use of professional learning best practices (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Dunst et al., 2015). Given the often-limited time available for professional learning, professional learning should be streamlined by carefully aligning the adopted HLPs and EBPs to support the prioritization of skills necessary for effective use of HLPs and EBPs.

Additional implications beyond adoption and competency activities are present within the implementing district and schools’ organizational processes, including data, communication, and engagement with families and community partners. Observation tools, self-report measures, and other tools that provide information on the use or implementation of HLPs and EBPs should be used to drive improvement. Routines for improvement, including data collection, analyses, and decision-making processes, need to be trained and supported to ensure effective and sustained use of HLPs and EBPs. A final implication can be found in leaders’ and educators’ communication and messaging. Communication regarding the adoption and ongoing use of HLPs and EBPs with instructional staff, families, caregivers, and community partners should include the rationale for their use, including their strength of evidence, how the use of HLPs will address student needs, how teachers are being supported within their use, and data monitoring of their use and intended impact for students. Many of these implications are system conditions, which, based on the limited results of the review, could benefit from further investigation.

5. Future Directions

5.1. Implications for Practice, Policy, and Funding

The current body of knowledge points to salient implications for educators, funders, and policymakers. While many EBPs were identified across HLP categories, several EBPs show promise in classrooms with diverse students. Namely, CRA frameworks and systematic instruction approaches were examined in multiple studies and have consistently demonstrated significant improvements in math performance across grade levels, as well as improvement in reading, literacy, and science for systematic instruction when it is paired with another approach (Mims et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2013). Moreover, when systematic instruction is combined with another instructional approach, such as culturally relevant or culture-based educational approaches, it has demonstrated benefits for students in math. Educators and practitioners may consider implementing these approaches in their classrooms or school, particularly for math or science. These culturally relevant approaches are particularly salient as an equitable classroom can be a haven for students with marginalized identities. Anticipating and incorporating diverse and intersecting identities in education supports the growth of all students, as implementing culturally relevant HLPs and EBPs can benefit students with and without marginalized identities (McLeskey et al., 2017).

In addition to utilizing EBPs, educators need to engage in reflective practice and critically examine which students have access to and are benefiting from the use of effective teaching practices. As part of this critical examination, the determination of contributing factors or root causes is necessary to address gaps within teacher use as well as enabling system mechanisms. Preparation programs, as well as in-service professional learning programs in both general and special education, need to be modified to include an explicit focus not only on these effective practices but also on the adaptation of them to be culturally responsive, authentic, and meet the needs of specific student populations. For policymakers, policy needs to be informed not only by empirical evidence but also by experience. The examination of feedback loops between policymakers and practitioners needs to be critically considered to ensure that the voices of those with lived experiences can be heard. For example, are strategies that address power differentials being deployed when holding community forums within historically marginalized communities? Funders, including federal, state, and philanthropic, can incentivize the use of effective teaching practices by stipulating the use and measurement of them within requests for proposals, including plans outlining the steps to be taken to ensure effective adaptation for historically marginalized groups of students.

5.2. Limitations and Implications for Research

This scoping review has several limitations. Despite conducting a broad search across 12 databases, Google Scholar, and publication repositories of research and philanthropic organizations, some papers may have been missed. We collated only the paper and study characteristics and findings reported by the authors and did not attempt to verify or validate the accuracy of the reported information. Finally, our analysis provides an overview of the nature and spread of research and gray literature. However, future research should consider assessing the level or strength of evidence regarding specific practices or interventions. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the results and conclusions of our review.

Overall, this study pointed toward the benefits of HLPs and EBPs for students, building on other research that illustrates the value of these practices in promoting positive student outcomes. For example, limited research suggests that the long-term effects of HLPs and EBPs on students include improved academic outcomes, enhanced social and emotional skills and peer relationships, increased engagement, improvement in student–teacher relationships, and reduction in achievement gaps (Bierman et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2017; Kuriloff et al., 2019; McLeskey et al., 2017). However, more longitudinal research focusing specifically on the impact of HLPs and EBPs on marginalized students is warranted.

Further, this study identified notable gaps in the research, particularly in the areas of science, social studies, and STEM across the body of literature identified. Further investigation is needed to identify effective HLPs and EBPs in these subject areas to ensure comprehensive support for students across all disciplines. Additionally, it is interesting to note that while nine studies examined social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes for students, there was minimal overlap in the EBPs and HLPs examined. This suggests a potential area for future research to explore the intersection of these outcomes and the specific practices that contribute to their improvement. By identifying the most effective HLPs and EBPs for social, emotional, and behavioral development, educators can better support students in these crucial areas.

Recognizing and addressing the gaps in HLPs and EBPs could enhance the effectiveness and quality of teaching practices implemented with all students in general, but especially marginalized students. As noted above, most HLP categories with evidence included general instructional practices. There was some evidence on social, emotional, and behavioral evidence and limited data focused on assessment practices. Limited data in student assessment practices can hinder educators’ ability to understand specific learning needs for students to provide appropriate support and interventions (Hamilton et al., 2009). Data-driven decision-making is crucial in education to identify areas requiring improvement and make informed instructional choices (Marsh et al., 2006). Addressing the issue of limited data in assessment practices for students with disabilities and marginalized students is critical to identifying areas of strength and weaknesses in students’ performance (Marsh et al., 2006). Without a comprehensive assessment, we might miss the mark to meet the unique needs of students, exacerbate the existing education gap, and fail to ensure equitable educational opportunities and support the individualized learning needs of all students.

Theoretical foundations play a crucial role in shaping HLPs and EBPs. Theories provide a framework and guiding principles for understanding how youth learn and interpret the effects of these practices. Educators can make informed decisions about teaching strategies, curriculum design, and instructional interventions by aligning them with theoretical frameworks that have empirical evidence. This alignment between theory and practice helps to establish a coherent approach, a common language, and a shared vision within an educational setting. Having a shared understanding of the theory behind an HLP or EBP can also contribute to the fidelity of implementation. When educators are familiar with the underlying theory, they can better implement HLPs and EBPs in a consistent and effective manner. Therefore, it is beneficial to continue to strengthen a unified framework of HLPs based on theories of learning and the social ecology of development, taking into consideration students’ intersecting identities. Interestingly, none of the papers explicitly discussed an HLP “framework,” but it would be valuable to have a cohesive and comprehensive framework that integrates various theories and principles for the effective implementation of HLPs.

Addressing the gaps in the research literature is crucial to ensure equity and inclusivity. Many articles fail to explicitly discuss equity, and there is an uneven representation of student groups in the research. Hispanic and Latino/a students, as well as White students, are overrepresented, highlighting the need for more research on Black, Indigenous, and other students of color. Additionally, students with physical or health disabilities and students from low socioeconomic backgrounds are under-represented in the literature. It is essential to conduct more studies exploring the effectiveness of HLPs and EBPs with these under-represented student groups. Targeting the needs of under-represented students not only benefits them but also enhances the learning experience for all students in a classroom. By addressing the unique challenges and strengths of these student groups, educators can create a more inclusive and supportive learning environment.

Furthermore, students cannot benefit from high-leverage, evidence-based practices that they do not receive. It is necessary that research, funding, and policy efforts work in tandem to ensure the translation of effective teaching practices into use within the classroom. Very few studies included an examination of the conditions that enable or provide the hospitable environment necessary for successful adoption and use of the identified teaching practices. The field of implementation science posits that a coherent infrastructure, that is, various system conditions or mechanisms working in concert with each other, is necessary to support the uptake and effective use of practices. For example, the Active Implementation Frameworks (Fixsen & Blase, 2020) outline that in addition to competency-building mechanisms of professional learning and coaching, other organizational and leadership mechanisms are necessary for creating enabling conditions. These mechanisms include data systems to support decision-making, leadership practices to address challenges and create solutions, clear communication and feedback loops, refinement of policies and procedures to support the practice, allocation of necessary resources, and collaborative engagement of family and community partners in the process. Holistic examinations of additional system conditions, due to their interconnected nature, are needed to support not only the uptake of effective practices for K-12 students but also sustained and scaled use.

In sum, future research should focus on the long-term impact of HLPs and EBPs for under-represented student populations who are under-represented in the current literature, and should further examine underexplored academic domains (e.g., social studies and STEM), the intersection of HLPs and EBPs, and the system conditions necessary to implement these practices. Further, future research should aim to develop an equity-based, theoretically sound unified framework for implementing HLPs and EBPs that benefits marginalized and under-represented students. This research would also support the development of data-driven policies that more intentionally address disparities in educational outcomes rooted in racism, classism, and ableism. These practices not only benefit individual students but also contribute to systemic changes that promote inclusivity in education.

5.3. Conclusions

In conclusion, this scoping review underscores the significant potential of HLPs and EBPs to enhance educational outcomes for marginalized students across various identities. With 85 studies identified that highlight the efficacy of these practices, it becomes clear that further exploration is necessary to optimize their application in diverse classroom settings. The findings suggest that while many HLPs and EBPs positively impact all students, targeted research is essential to understand their effectiveness for under-represented groups, particularly in subjects like science and social studies. The implications for practice, policy, and funding also emphasize the need for high-quality instructional materials, professional development opportunities, and a supportive organizational infrastructure to facilitate effective implementation. Addressing the existing gaps in research and ensuring equitable access to these practices are crucial steps toward fostering an inclusive educational environment that not only meets the needs of marginalized students but also enriches the learning experiences of all students. Pursuing a cohesive framework for HLPs and EBPs, grounded in equity and informed by diverse theoretical perspectives, can drive systemic change and promote a more equitable educational landscape.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci15030266/s1, Table S1: Evidence-Based Programs Overview; Document S1: Example Electronic Search Strategy; Checklist S1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: E.K.M., X.F.-J. and C.W.; Methodology: E.K.M., X.F.-J., J.T.D. and C.W.; Formal Analysis: E.K.M., X.F.-J. and J.T.D.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: E.K.M., X.F.-J., J.T.D., A.R.R. and C.W.; Writing—Review and Editing: E.K.M., X.F.-J., J.T.D., A.R.R. and C.W.; Visualization: E.K.M., X.F.-J. and J.T.D.; Supervision: E.K.M., X.F.-J. and C.W.; Project Administration: X.F.-J. and C.W.; Funding Acquisition: X.F.-J. and C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Center for Learner Equity under Grant INV-044903.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aceves, T. C., & Orosco, M. J. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching (Document No. IC-2). University of Florida, Collaboration for Effective Educator, Development, Accountability, and Reform Center. Available online: https://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/innovation-configurations/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Al Otaiba, S., Rouse, A. G., & Baker, K. (2018). Elementary grade intervention approaches to treat specific learning disabilities, including dyslexia. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(4), 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L. K. (2022). Using UDL to plan a book study lesson for students with intellectual disabilities in inclusive classrooms. Teaching Exceptional Children, 54(4), 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balu, R., Zhu, P., Doolittle, F., Schiller, E., Jenkins, J., & Gersten, R. (2015). Evaluation of response to intervention practices for elementary school reading. NCEE 2016-4000. National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. Available online: https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/RtI_2015_Full_Report_Rev_21064000.pdf.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Benner, G. J., Michael, E., Ralston, N. C., & Lee, E. O. (2022). The impact of supplemental word recognition strategies on students with reading difficulties. International Journal of Instruction, 15(1), 837–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierman, K. L., Heinrichs, B. S., Welsh, J. A., Nix, R. L., & Gest, S. D. (2017). Enriching preschool classrooms and home visits with evidence-based programming: Sustained benefits for low-income children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(2), 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bismarck, S. F., & Prosser, S. K. (2023). Analyzing unexpected data after a novel mathematics lesson using the critical friend process. Educational Research Quarterly, 45(1), 3–19. Available online: http://erquarterly.org/index.php?pg=content (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Boon, R. T., Paal, M., Hintz, A.-M., & Cornelius-Freyre, M. (2015). A review of story mapping instruction for secondary students with LD. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 13(2), 117–140. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1085222.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Bouck, E. C., Bassette, L., Shurr, J., Park, J., Kerr, J., & Whorley, A. (2017). Teaching equivalent fractions to secondary students with disabilities via the virtual-representational-abstract instructional sequence. Journal of Special Education Technology, 32(4), 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browder, D. M., Wood, L., Thompson, J., & Ribuffo, C. (2014). Evidence-based practices for students with severe disabilities (Document No. IC-3). University of Florida, Collaboration for Effective Educator, Development, Accountability, and Reform Center. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E. B., & Doolittle, J. (2008). A cultural, linguistic, and ecological framework for response to intervention with English language learners. Teaching Exceptional Children, 40(5), 66–72. Available online: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1078&context=edu_fac (accessed on 15 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Brownell, M., Kiely, M. T., Haager, D., Boardman, A., Corbett, N., Algina, J., Dingle, M. P., & Urbach, J. (2017). Literacy learning cohorts: Content-focused approach to improving special education teachers’ reading instruction. Exceptional Children, 83(2), 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, A. L., Vogelgesang, K., Fernando, J., & Lugo, W. (2016). Using data to individualize a multicomponent, technology-based self-monitoring intervention. Journal of Special Education Technology, 31(2), 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Y. N., & Fagan, Y. M. (2013). The effects of an integrated reading comprehension strategy: A culturally responsive teaching approach for fifth-grade students’ reading comprehension. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 57(2), 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, K. M., Shogren, K. A., & Carlson, S. (2021). Examining types of goals set by transition-age students with intellectual disability. Career Development & Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 44(3), 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, M. K., Maki, K. E., Brann, K. L., McComas, J. J., & Helman, L. A. (2020). Comparison of reading growth among students with severe reading deficits who received intervention to typically achieving students and students receiving special education. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 53(6), 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, W. S., Hord, C., & Watts-Taffe, S. (2021). Increasing secondary students’ comprehension through explicit attention to narrative text structure. Teaching Exceptional Children, 54(6), 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, C. M. (2016). Does culturally relevant teaching work? An examination from student perspectives. Sage Open, 6(3), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, R. M. (2005). Tracking and high school English learners: Limiting opportunity to learn. American Educational Research Journal, 42(2), 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, J., & Ruiz, N. T. (2020). “Wait! I don’t get it! Can we translate?”: Explicit collaborative translation to support emergent bilinguals’ reading comprehension in the intermediate grades. Bilingual Research Journal, 43(2), 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, M. E., Lo, Y., Walker, V. L., Masud, A. B., & Tapp, M. C. (2023). Effects of check-in/check-out on the behavior of students with autism spectrum disorder who have extensive support needs. Psychology in the Schools, 60(9), 3504–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro, E. A., Smolkowski, K., Gunn, B., Dennis, C., & Vadasy, P. (2022). Evaluating the efficacy of an english language development program for middle school english learners. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 27(4), 322–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciullo, S., & Mason, L. (2017). Prioritizing elementary school writing instruction: Cultivating middle school readiness for students with learning disabilities. Intervention in School & Clinic, 52(5), 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, A. M., Tapp, M. C., Pennington, R. C., Spooner, F., & Teasdell, A. (2021). A systematic review of modified schema-based instruction for teaching students with moderate and severe disabilities to solve mathematical word problems. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 46(2), 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, C. M., Alberto, P. A., Compton, D. L., & O’Connor, R. E. (2014). Improving reading outcomes for students with or at risk for reading disabilities: A synthesis of the contributions from the institute of education sciences research centers. NCSER 2014-3000. National Center for Special Education Research. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=NCSER20143000 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Cook, B. G., & Cook, S. C. (2013). Unraveling evidence-based practices in special education. The Journal of Special Education, 47(2), 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R. (2016). Complicating conditions: Obstacles and interruptions to low-income students’ college “choices”. The Journal of Higher Education, 87(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-Carlino, Y., Mustian, A. L., Allen, R. D., & Gilbert, J. (2016). I have a voice and can speak up for myself through writing! Intervention in School & Clinic, 51(4), 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, M. D., & Green, A. L. (2021). A systematic review of evidence-based practices for students with learning disabilities in social studies classrooms. Social Studies, 112(3), 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., Gardner, M., & Espinoza, D. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. Available online: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/effective-teacher-professional-development-report (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Delbridge, A., & Helman, L. (2016). Evidence-based strategies for fostering biliteracy in any classroom. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44(4), 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domitrovich, C. E., Harris, A. R., Syvertsen, A. K., Morgan, N., Jacobson, L., Cleveland, M., Moore, J. E., & Greenberg, M. T. (2022). Promoting social and emotional learning in middle school: Intervention effects of facing history and ourselves. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 51(7), 1426–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunst, C. J., Bruder, M. B., & Hamby, D. W. (2015). Metasynthesis of in-service professional development research: Features associated with positive educator and student outcomes. Educational Research and Reviews, 10(12), 1731–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrapala, S., Bruhn, A. L., & Rila, A. (2022). Behavioral Self-Regulation: A comparison of goals and self-monitoring for high school students with disabilities. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders, 30(3), 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evmenova, A. S., Graff, H. J., & Behrmann, M. M. (2017). Providing access to academic content for high-school students with significant intellectual disability through interactive videos. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities, 32(1), 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixsen, D. L., & Blase, K. A. (2020). Active implementation frameworks. In Handbook on implementation science (pp. 62–87). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, M. M., Hinton, V. M., Terry, S. L., & Strozier, S. D. (2014). Using the concrete-representational-abstract sequence and the strategic instruction model to teach computation to students with autism spectrum disorders and developmental disabilities. Education & Training in Autism & Developmental Disabilities, 49(4), 547–554. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:12885355 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Foorman, B., Espinosa, A., Wood, C., & Wu, Y. C. (2016). Using computer-adaptive assessments of literacy to monitor the progress of english learner students. REL 2016-149. Regional Educational Laboratory Southeast. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=REL2016149 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Gann, C. J., Gaines, S. E., Antia, S. D., Umbreit, J., & Liaupsin, C. J. (2015). Evaluating the effects of function-based interventions with deaf or hard-of-hearing students. Journal of Deaf Studies & Deaf Education, 20(3), 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Garwood, J. D., Brunsting, N. C., & Fox, L. C. (2014). Improving reading comprehension and fluency outcomes for adolescents with emotional-behavioral disorders: Recent research synthesized. Remedial & Special Education, 35(3), 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazewski, K. D., & Ertmer, P. A. (2020). Fostering complex problem solving for diverse learners: Engaging an ethos of intentionality toward equitable access. Educational Technology Research & Development, 68(2), 679–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L., Halverson, R., Jackson, S., Mandinach, E., Supovitz, J., & Wayman, J. (2009). Using student achievement data to support instructional decision making (NCEE 2009-4067). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Available online: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/publications/practiceguides/ (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Hinton, V. M., & Flores, M. M. (2019). The effects of the concrete-representational-abstract sequence for students at risk for mathematics failure. Journal of Behavioral Education, 28(4), 493–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C., Bailey, C. M., Warren, P. Y., & Stewart, E. A. (2020). “Value in diversity”: School racial and ethnic composition, teacher diversity, and school punishment. Social Science Research, 92, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingles, K. E., Gilson, C. B., & Pena, H., Jr. (2022). MADE 2 FADE: A practical strategy for empowering independence for students with disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 55(1), 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, M., Marino, M., Delisio, L., & Serianni, B. (2014). Supporting content learning through technology for K-12 students with disabilities (Document No. IC-10). University of Florida, Collaboration for Effective Educator, Development, Accountability, and Reform Center. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, B. A., & Besaw, J. (2020). Building early numeracy through virtual manipulatives for students with intellectual disability and autism. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 55(1), 28–44. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26898712 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Jones, S. M., Barnes, S. P., Bailey, R., & Doolittle, E. J. (2017). Promoting social and emotional competencies in elementary school. The Future of Children, 27(1), 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, L. M., & Ross, K. M. (2018). Teaching middle school students with learning disabilities to comprehend text using self-questioning. Intervention in School & Clinic, 53(5), 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephson, J., Wolfgang, C., & Mehrenberg, R. (2018). Strategies for supporting students who are twice-exceptional. Journal of Special Education Apprenticeship, 7(2). Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1185416.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Kana ‘iaupuni, S. M., Ledward, B., & Malone, N. (2017). Mohala i ka wai: Cultural advantage as a framework for Indigenous culture-based education and student outcomes. American Educational Research Journal, 54(1), 311S–339S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasari, C., Shire, S., Shih, W., & Almirall, D. (2021). Getting SMART about social skills interventions for students with asd in inclusive classrooms. Exceptional Children, 88(1), 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S., More, C., & Baker, J. N. (2022). Using embedded trials and systematic prompting to promote tacted and intraverbal responses for students with developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 57(1), 104–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, L., Evans, S. W., Lewis, T. J., State, T. M., Mehta, P. D., Weist, M. D., Wills, H. P., & Gage, N. A. (2021). Evaluation of a comprehensive assessment-based intervention for secondary students with social, emotional, and behavioral problems. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 29(1), 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S. (2016). Multiple-stimulus without replacement preference assessment for students at risk for emotional disturbance. Journal of Behavioral Education, 25(4), 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingbeil, D. A., January, S.-A. A., & Ardoin, S. P. (2020). Comparative efficacy and generalization of two word-reading interventions with English learners in elementary school. Journal of Behavioral Education, 29(3), 490–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingenberg, O. G., Holkesvik, A. H., & Augestad, L. B. (2019). Research evidence for mathematics education for students with visual impairment: A systematic review. Cogent Education, 6(1), 1626322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J. E., Yan, C., Serceki, A., & Swanson, H. L. (2021). Word-problem-solving interventions for elementary students with learning disabilities: A selective meta-analysis of the literature. Learning Disability Quarterly, 44(4), 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawec, J., & Montague, M. (2014). The role of teacher training in cognitive strategy instruction to improve math problem solving. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice (Wiley-Blackwell), 29(3), 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, E. M., & Carter, E. W. (2019). Review of interventions supporting secondary students with intellectual disability in general education classes. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 44(2), 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriloff, P., Jordan, W., Sutherland, D., & Ponnock, A. (2019). Teacher preparation and performance in high-needs urban schools: What matters to teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 83, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liasidou, A. (2013). Bilingual and special educational needs in inclusive classrooms: Some critical and pedagogical considerations. Support for Learning, 28(1), 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A. C. J., Miller, F. G., & Upright, J. J. (2019). Classroom management for ethnic-racial minority students: A meta-analysis of single-case design studies. School Psychology, 34(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J. A., Pane, J. F., & Hamilton, L. S. (2006). Making sense of data-driven decision making in education: Evidence from recent RAND research. RAND Corporation. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/occasional_papers/OP170.html (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- McGrath, P. J., & Elgar, F. J. (2015). Effects of socio-economic status on behavior problems. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, K., Girvan, E. J., Horner, R. H., & Smolkowski, K. (2014). Education not incarceration: A conceptual model for reducing racial and ethnic disproportionality in school discipline. Journal of Applied Research on Children, 5(4), 4. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2598212 (accessed on 15 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- McLeskey, J., Barringer, M.-D., Billingsley, B., Brownell, M., Jackson, D., Kennedy, M., Lewis, T., Maheady, L., Rodriguez, J., Scheeler, M. C., Winn, J., & Ziegler, D. (2017). High-leverage practices in special education. Council for Exceptional Children & CEEDAR Center. Available online: https://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/CEC-HLP-Web.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- McLeskey, J., Billingsley, B., Brownell, M. T., Maheady, L., & Lewis, T. J. (2019). What are high-leverage practices for special education teachers and why are they important? Remedial and Special Education, 40(6), 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mims, P. J., Stanger, C., Sears, J. A., & White, W. B. (2018). Applying systematic instruction to teach ELA skills using fictional novels via an iPad app. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 37(4), 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mize, M., & Glover, C. (2021). Supporting black, indigenous, and students of color in learning environments transformed by COVID-19. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 23(1), 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschkovich, J. (2013). Principles and guidelines for equitable mathematics teaching practices and materials for English language learners. Journal of Urban Mathematics Education, 6(1), 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narkon, D. E., & Wells, J. C. (2013). Improving reading comprehension for elementary students with learning disabilities: UDL enhanced story mapping. Preventing School Failure, 57(4), 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, G., Cook, S. C., Zarate, K., Powell, S. R., Maggin, D. M., Drake, K. R., Kiss, A. J., Ford, J. W., Sun, L., & Espinas, D. R. (2022). A systematic review of meta-analyses in special education: Exploring the evidence base for high-leverage practices. Remedial and Special Education, 43(5), 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochsendorf, R., & Taylor, K. (2016). A summary of professional development research, fy 2006-fy 2016. National Center for Special Education Research. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/ncser/pdf/PD_2016.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Odom, S. L., Duda, M. A., Kucharczyk, S., Cox, A. W., & Stabel, A. (2014). Applying an implementation science framework for adoption of a comprehensive program for high school students with autism spectrum disorder. Remedial & Special Education, 35(2), 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, L. M., Lee-St. John, T., Raczek, A. E., Luna Bazaldua, D. A., & Walsh, M. (2016). Examining the role of early academic and non-cognitive skills as mediators of the effects of city connects on middle school academic outcomes. Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED567236.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Orlando, A., & Ruppar, A. (2016). Literacy instruction for students with multiple and severe disabilities who use augmentative/alternative communication (Document No. IC-16). University of Florida, Collaboration for Effective Educator, Development, Accountability, and Reform Center. Available online: https://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/IC-Literacy-multiple-severe-disabilities.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Orosco, M. J., & O’Connor, R. (2014). Culturally responsive instruction for English language learners with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 47(6), 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, R. K., Caldarella, P., Hansen, B. D., & Wills, H. P. (2020). Managing student behavior in a middle school special education classroom using CW-FIT Tier 1. Journal of Behavioral Education, 29(1), 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A. (2001). English language learners with special needs: Effective instructional strategies. ERIC Digest. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED469207 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Osher, D., Moroney, D., & Williamson, S. (2018). Creating safe, equitable, engaging schools: A comprehensive, evidence-based approach to supporting students. Harvard Education Press. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?redir=https%3a%2f%2fwww.hepg.org%2fhep-home%2fbooks%2fcreating-safe%2c-equitable%2c-engaging-schools (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Owens, J., & McLanahan, S. S. (2020). Unpacking the drivers of racial disparities in school suspension and expulsion. Social Forces: A Scientific Medium of Social Study and Interpretation, 98(4), 1548–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, C. (1984). Multicultural education and racism in American schools. Theory Into Practice, 23(2), 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, S. V., Rao, S., & Protacio, M. S. (2015). Converging recommendations for culturally responsive literacy practices: Students with learning disabilities, English language learners, and socioculturally diverse learners. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 17(3), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project ELLIPSES, Project LEE & Project ELITE2. (2020). Meeting the needs of English learners with and without disabilities: Brief 2, Evidence-based Tier 2 intervention practices for English learners. U.S. Office of Special Education Programs. Available online: http://www.projectlee.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Series2-Brief2_Final.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Rappaport, S., Grossman, J., Garcia, I., Zhu, P., Avila, O., & Granito, K. (2017). Group work is not cooperative learning: An evaluation of power teaching in middle schools. Investing in innovation (i3) evaluation. MDRC. Available online: https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/SFA-Math_Power%20Report.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Reyhner, J. (2017). Affirming identity: The role of language and culture in American Indian education. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1340081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards-Tutor, C., Aceves, T., & Reese, L. (2016). Evidence-based practices for English Learners (Document No. IC-18). University of Florida, Collaboration for Effective Educator, Development, Accountability, and Reform Center. Available online: http://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/tools/innovation-configurations/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Roncoroni, J., Hernandez-Julian, R., Hendrix, T., & Whitaker, S. W. (2021). Breaking barriers: Evaluating a pilot stem intervention for Latino children of Spanish-speaking families. Journal of Science Education & Technology, 30(5), 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, T., Kena, G., Rathbun, A., KewalRamani, A., Zhang, J., Kristapovich, P., & Manning, E. (2012). Higher education: Gaps in access and persistence study (NCES 2012-046). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Government Printing Office. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2012/2012046.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Satsangi, R., Hammer, R., & Hogan, C. D. (2018). Studying virtual manipulatives paired with explicit instruction to teach algebraic equations to students with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 41(4), 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, A., Wexler, J., Kurz, L. A., & Swanson, E. (2021). Incorporating evidence-based literacy practices into middle school content areas. Teaching Exceptional Children, 53(4), 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M., & Bryant, D. P. (2017). Improving the fraction word problem solving of students with mathematics learning disabilities. Remedial & Special Education, 38(2), 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shogren, K. A., Raley, S. K., Burke, K. M., & Wehmeyer, M. L. (2018). The self-determined learning model of instruction: Teacher’s guide. Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities. Available online: https://selfdetermination.ku.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Teachers-Guide-2019-Updated-Logos.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Shogren, K. A., Wehmeyer, M. L., Palmer, S. B., Forber-Pratt, A. J., Little, T. J., & Lopez, S. (2015). Causal agency theory: Reconceptualizing a functional model of self-determination. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 50(3), 251–263. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24827508 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Smith, B. R., Spooner, F., Jimenez, B. A., & Browder, D. (2013). Using an early science curriculum to teach science vocabulary and concepts to students with severe developmental disabilities. Education & Treatment of Children, 36(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefano, M. D., Litster, K., & MacDonald, B. L. (2017). Mathematics intervention supporting Allen, a Latino EL: A case study. Education Sciences, 7(2), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M. A., & Hansen-Thomas, H. (2016). Sanctioning a space for translanguaging in the secondary english classroom: A case of a transnational youth. Research in the Teaching of English, 50(4), 450–472. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24889944 (accessed on 15 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Stoker, G., Arellano, B., & Lee Hoon, D. (2022). English language development among american indian English learner students in New Mexico. Rel 2022-135. Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=REL2022135 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Strong, A. H., Wehby, J. R., & Falk, K. B. (2016). Reading fluency interventions for middle school students with academic and behavioral disabilities. Reading Improvement, 53(2), 53–64. Available online: https://projectinnovation.com/reading-improvement (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Tejero Hughes, M., & Parker-Katz, M. (2013). Integrating comprehension strategies into social studies instruction. Social Studies, 104(3), 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrazas-Arellanes, F. E., Gallard, A. J., Strycker, L., & Walden, E. (2017). ESCOLAR: Improving education equity for students with disabilities and English learners through online science units. AERA Online Paper Repository. Available online: http://www.aera.net/Publications/Online-Paper-Repository/AERA-Online-Paper-Repository (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- The New Teacher Project. (2021). Accelerate, don’t remediate: New evidence from elementary math classrooms. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED615462.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Thompson, J., Mawyer, K., Johnson, H., Scipio, D., & Luehman, A. (2021). C2AST (critical and cultural approaches to ambitious science teaching): From responsive teaching toward developing culturally and linguistically sustaining science teaching practices. Science Teacher, 89(1), 58–64. Available online: https://www.nsta.org/science-teacher/science-teacher-septemberoctober-2021/c2ast-critical-and-cultural-approaches (accessed on 15 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Education. (2024). Civil rights laws. U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://www.ed.gov/laws-and-policy/civil-rights-laws (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Vander Hart, N., & Power, M. (2022). Teaching writing strategies with tiered supports for middle school students with and without special needs: A case study. Preventing School Failure, 66(2), 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, S., Danielson, L., Zumeta, R., & Holdheide, L. (2015). Deeper learning for students with disabilities (Deeper learning research series). Jobs for the Future. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED560790 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Vaughn, S., Swanson, E., Fall, A.-M., Roberts, G., Capin, P., Stevens, E. A., & Stewart, A. A. (2022). The efficacy of comprehension and vocabulary focused professional development on English learners’ literacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(2), 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Works Clearinghouse, Institute of Education Sciences & U.S. Department of Education. (2017, November). Students with a specific learning disability intervention report: Self-regulated strategy development. Available online: https://whatworks.ed.gov/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).