Abstract

In the last decade, a growing number of schools have begun implementing dual language education (DLE), and studies have shown evidence of the benefits of DLE for elementary education students. However, existing research syntheses do not focus on DLE in the early years (pre-Kindergarten and Kindergarten), considering young bilingual children’s development and learning characteristics. In this paper, a novel conceptual framework is used to explore the extant literature on DLE in the early years moving beyond Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory to consider additional characteristics relating to bilingual children’s development and learning. A systematic literature review was conducted following a rigorous procedure, resulting in nine studies that met the inclusion criteria. Information about each study was coded and analyzed. The results describe the studies’ sample characteristics, research design, and findings organized by students’ academic skills (i.e., language, literacy, and mathematics), dual language classroom practices, and parents’ perceptions of DLE. This paper highlights current knowledge of DLE programs in the early years, identifies gaps, and offers recommendations for future research, policy, and practice.

1. Introduction

In the United States, about 32 percent of the young child population (ages 0 to 8) are growing up using two or more languages (Park et al., 2017). Some states have larger percentages; for example, California and Texas have the highest population of young bilinguals with 60 and 50 percent, respectively. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES, 2022) found that the number of students classified as English Learners (ELs) increased between fall 2010 (4.5 million students; 9.2%) and fall 2019 (5.1 million students; 10.4%). Most of these students come from Latine,1 Spanish-speaking homes (3.9 million students; 75.7% of ELs). Enrollment of Latine students has grown from 6.0 million in 1995 to 13.6 million in fall 2017 (the last year of data available). Since then, Latine students represent 26.8% of public school enrollment, and as projected by the NCES, Latine enrollment will continue to grow, reaching 14 million (27.5%) of public school enrollment by fall 2029 (Wang & Dinkes, 2020).

In addition to Spanish (75.5%), approximately 25% of students spoke a language other than English (LOTE). The second most reported LOTE spoken by students was Arabic. Chinese (100,100 students), Vietnamese (75,600 students), Portuguese (44,800 students), Russian (39,700 students), Haitian (31,500 students), Hmong (30,800 students), Korean (25,800 students), and Urdu (25,192 students) were the next most reported LOTE spoken by EL students in fall 2020.

Linguistic diversity is not a new phenomenon in the United States; it has been part of the country’s history since before European colonization. Historically, however, language has been used as a tool for oppression in societies during colonialism and migration processes. In the United States, racialized language policies were established by the colonizers to assimilate and marginalize, first, peoples of the Native Nations, then, Africans who were enslaved, Mexicans in the southern territories of the United States, and immigrants whose first languages were not English (Rodriguez-Arroyo & Pearson, 2020). Their policies included forbidding or punishing people for speaking their native language, denying them the opportunity to be educated in their language, and forcing them to learn English as the only vehicle to engage in commerce or hold positions in society. The marginalized language communities resisted, and over the years, these policies became less restrictive based on political, economic, and demographic changes (Gándara & Escamilla, 2017).

Consequently, bilingual education (i.e., the use of two languages to teach academic content) policies evolved unevenly across states, ranging from those states supporting only English acquisition to those promoting bilingualism and biliteracy for both monolingual English-speaking children and speakers of other languages. Bilingualism is defined in this paper as the ability to speak two languages at any level of proficiency, and biliteracy is the ability to read and write in two languages. Within the range of programs offered under bilingual education policies (Baker & Wright, 2021), this review focuses only on programs with bilingualism and biliteracy as the goal, educating children in both languages. Different modalities and terms are used to refer to this type of bilingual program in different states and the academic literature. In this paper, we use the term “dual language education” (DLE) to refer to dual language immersion programs (DLI), two-way immersion (TWI), and one-way immersion. Two-way immersion involves a balanced mix of students from two different language backgrounds with the goal of achieving bilingual proficiency. We chose to focus on this type of program because it is linguistically and culturally sustaining and was designed to level the power relation between children’s languages (the minoritized language and dominant American English). Thus, this review does not focus on other types of bilingual education, such as transitional bilingual programs or English with LOTE support programs whose primary goal is English acquisition.

In the last decade, DLE has gained attention, and there is a growing number of schools implementing it, although there is variability in the way DLE programs are designed and implemented. Studies have provided evidence of the benefits of DLE for students in the elementary grades, particularly in enhancing academic achievement and bilingual proficiency (e.g., Arias & Fee, 2018; Morales, 2024; He et al., 2021). However, existing research syntheses do not focus on DLE in the early years (preschool programs; ages 3–5) with consideration given to the development and learning of young bilingual children. As an example, in a recent research synthesis on bilingual education and bilingualism conducted by Baker et al. (2016), only one of five studies included samples of children in preschool programs that examined the effect of participating in a TWI program on bilingual children’s language and literacy outcomes; the other four studies included bilingual children attending transitional bilingual and English immersion or English-only programs. We will further discuss the findings of previous research syntheses in the following sections.

In this paper, we will report findings from a systematic literature review conducted following a rigorous procedure to synthesize current knowledge, identify gaps, and offer recommendations for future research. The research questions guiding this systematic review are as follows: (1) What is the state of knowledge on DLE in early childhood [pPre-Kindergarten (pre-K) and Kindergarten (K)] in the United States? (2) What are the gaps in knowledge related to DLE in early childhood? (3) What are the implications for policy, research, and practice?

1.1. Theoretical and Empirical Frameworks

Existing developmental theories and conceptual frameworks focused on the role of bilingualism in children’s early development provide little attention to language policies and practices involving the early care and education of bilingual children from minoritized and marginalized populations (Castro & Meek, 2022). The present systematic review of the literature on the effects of DLE on young bilingual children’s developmental and academic outcomes is guided by a new conceptual framework focused specifically on the role of bilingualism in young children’s development (Castro et al., 2024), which is informed by, yet also expands, Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory and Coll et al. (1996) integrative model for studying the developmental competencies of minoritized children. Castro et al.’s (2024) framework informs this systematic research review by focusing on three interpenetrated elements: sociocultural contexts that bilingual children experience (i.e., societal, community, family, and early care and education experiences including linguistic racism), individual characteristics (i.e., personality, motivation), and developmental characteristics unique to their bilingualism.

Empirical research establishing effective practices to provide high-quality early education to bilingual children will also guide this systematic review (e.g., Buysse et al., 2014; Castro et al., 2017). In the following sections, we discuss relevant research syntheses conducted in the last two decades that have established the benefits of using bilingual children’s first language in instruction and supporting children’s bilingualism and biliteracy.

1.2. Previous Research on Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

Evidence from research syntheses and meta-analyses conducted in the last two decades has established that the use of bilingual children’s native language in instruction is associated with larger improvements in their language, literacy, and overall achievement outcomes. These associations were found both in their native language and English when compared to bilinguals attending English-only instruction without support for the development of their native language (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017). It is important to note that most of the studies included in these research syntheses focused on English language and literacy outcomes with no assessments conducted in children’s native or first language as an outcome of interest. Furthermore, reading was the most frequently assessed outcome, with only a few studies providing data on children’s writing, mathematics, and science learning (e.g., Morita-Mullaney et al., 2022).

Research on language-of-instruction models in the education of bilingual children has mostly been conducted with school-age children and has served as the foundation for the implementation of various language-of-instruction approaches in early childhood (pre-K-K) by school districts and in early childhood programs. For example, the Office of Head Start’s National Center on Cultural and Linguistic Responsiveness (NCCLR, 2015) developed policies and program practices to guide Early Head Start and Head Start programs in the design and implementation of Classroom Language Models (CLMs) that would address the linguistic characteristics of bilingual and monolingual children and should be tailored to the particular linguistic configuration of each classroom. The NCCLR states that CLMs should be “part of a program-wide, planned approach that promotes children’s optimal language and early literacy development” (p. 3). The proposed CLMs include the following: (1) English with home language support, in which English language development is the goal with the home language used for behavioral guidance and social interaction; (2) dual language instruction, in which the goal is that all children become bilingual in English and another language; (3) home language as the foundation for English development, recommended for children from birth to 3 years of age growing up with a home language other than English to develop strong language skills that serve as a foundation for second language development; and (4) English-only instruction recommended for children from birth to 5 years of age when all children are monolingual English speakers.

1.3. Dual Language Education as an Instructional Model

DLE programs utilize a dual immersion approach that provides instruction in both English and a partner language. There are two types of DLE programs: one-way DLE programs and two-way DLE programs as reported by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2017). One-way DLE programs primarily serve students from one home language group (e.g., students learning English and their home language); on the other hand, two-way dual language programs serve students from two different language backgrounds (typically native English speakers and native speakers of another language). Two-way DLE programs follow different models with a 50/50 model (i.e., 50% instruction in the partner language and 50% instruction in English), a 70/30 model (i.e., 70% instruction in the partner language and 30% instruction in English), and a 90/10 model (i.e., 90% instruction in the partner language and 10% instruction in English). The 70/30 and the 90/10 models transition to a 50/50 model as students progress through their school years. The one-way DLE program typically follows a 90/10 model. The time allocated for each language in the 50/50 model may be divided in various ways: half a day in the partner language and half a day in English, alternating one day in the partner language and one day in English. In other cases, where the number of teachers is limited, the language of instruction is alternated every other week. Some programs have two teachers who work as a team (i.e., one teacher provides instruction in the partner language, and the other teacher provides instruction in English), while other programs have one bilingual teacher who splits the instruction between both languages (Gómez et al., 2005).

In their 2021 report, the American Councils Research (ARC) center indicated that there were an estimated 3000 K-12 (ages 6–18) dual language immersion programs across the United States public schools serving approximately 5 million students who are ELs. Forty-four states reported having DLE programs, with California (660), Texas (521), New York (456), Utah (297), and North Carolina (229) accounting for 60% of the programs. Spanish was the most common language of instruction offered within 2936 DLE programs across 35 states, followed by Chinese (14 states), Native American languages (12 states), and French (7 states) as the partner languages. However, little is known about the number of early childhood programs across the United States that provide dual language programming (ARC, 2021).

1.4. Present Study

The purpose of this review was to synthesize current knowledge, identify gaps, and offer recommendations for future research regarding the effect of DLE programming on young children in the United States. We include the results of a systematic literature review focused on DLE programs in early childhood (pre-K and K; ages 3–5). The review included articles published from 2007 to 2022.

Establishing effective, equitable practices to provide high-quality early education to bilingual children was a key component of this systematic review. This review is an essential first step to understanding the landscape of DLE programming for young bilingual children and to guide key stakeholders in designing dual language programs that provide the support needed for the growing number of young bilingual children who attend these programs.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

The literature search was conducted from October 2022 to February 2023 using the following databases and search engines: JSTOR, Academic Search Premier, PsycArticles, PsycINFO, ERIC, and Google Scholar. Search terms were grouped into the following categories: program type (early childhood, Head Start), grades (pre-K, preschool, or K), instructional models (bilingual education, DLE, dual language immersion, one-way dual language immersion, or two-way dual language immersion), language background (bilingual, dual language learner, multilingual, or Spanish), and the children’s race or ethnicity (American Indian, Asian, Black, African American, Hispanic, Indigenous, Latino/a, Latin, Latinx, Latine, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander). An exhaustive literature search involved a full-text search of all applicable research databases using all search terms and combinations of terms generated by the research team. Additional search procedures included using titles and keywords, advanced search options, the “find similar articles” feature, and cross-referencing articles in selected studies.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included in this review if published in 2007 or later in peer-reviewed journals. Other additional criteria included quantitative and mixed methods studies, a focus on DLE programming for bilingual children in early childhood (pre-K–K), and studies that evaluated the effects of DLE in early childhood. Book chapters, dissertations, and other gray literature and conceptual papers were excluded.

2.3. Screening and Eligibility

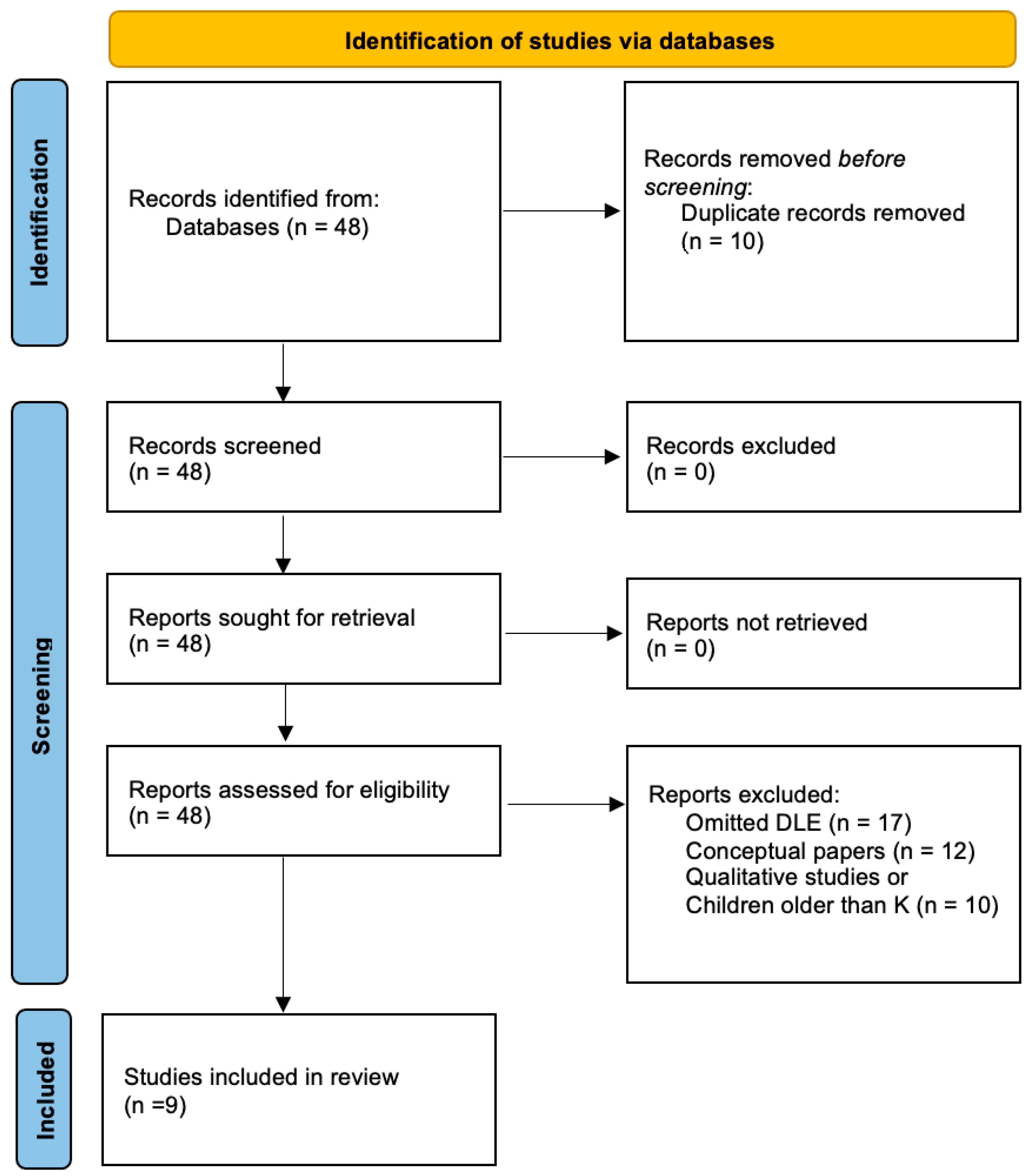

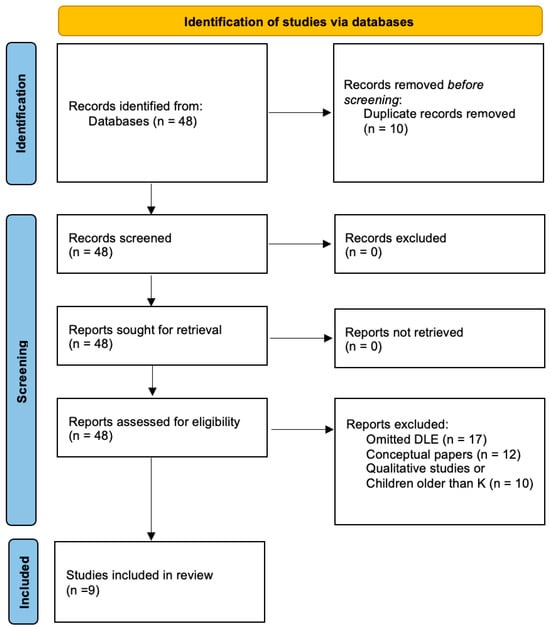

After literature deduplication, three reviewers screened the titles and abstracts against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. A fourth reviewer was consulted to reconcile discrepancies. Three authors screened and reviewed the full articles for inclusion/exclusion. Different research team members completed two rounds of coding to ensure the thoroughness and accuracy of the final list of articles before conducting the analyses and summarizing the results. The initial search yielded 48 studies, of which 17 were excluded because they discussed bilingual education but did not include DLE programs. Additionally, 12 articles were conceptual papers and were thus also excluded. Ten other articles reporting qualitative studies and studies including only children above kindergarten were excluded (see Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

The search yielded nine peer-reviewed articles that met the literature review’s selection criteria. All articles were reviewed, and information about each study was coded into an Excel spreadsheet to be analyzed. A summary table was created and included the following study elements: purpose, research design, study participants/setting characteristics, outcome measures/methods, and results (see Table A1).

3. Results

A description of the studies included in this systematic literature review is presented in Table A1 in the Appendix A and includes a description of the research design elements for the reviewed quantitative and mixed-methods design studies. The results are organized by sample characteristics, study design, and findings on child outcomes (i.e., language, literacy, and mathematics), dual language classroom practices, and parents’ perceptions of dual language education. There were a number of methodological limitations in the studies reviewed that should be taken into consideration in the interpretation of these results, which are presented in the Discussion section.

3.1. Sample Characteristics

All studies included bilingual children (n = 9; 100%); some also included English monolingual children. Only one study (n = 1; 11%) involved parents as participants. All studies involved children whose partner language was Spanish. Regarding the children’s grades, four of the nine studies (44%) included pre-K children only, and 56% included kindergarten and/or older children. While the school year offers some insight into children’s developmental stages, it is important to note that some studies (e.g., Nascimento, 2016; Serafini et al., 2022) did not include information about their ages. Table A1 shows this information per study. Finally, the sample size of the participating children varied widely across the quantitative and mixed-method studies reviewed, ranging from 9 (Anderberg & Ruby, 2013) to 18,588 students (Serafini et al., 2022). Power analyses to determine sample sizes were not reported in most of the studies.

3.2. Research Design

Most reviewed studies (n = 7, 78%) involved group comparison designs. Among these studies, only two followed procedures to warrant, to some degree, causal inferences between the DLE program and outcome variables. Specifically, Barnett et al. (2007) used an experimental design in which children were randomly assigned to a DLE program or control group, and Morita-Mullaney et al. (2022) used propensity score matching to balance the group exposed to the DLE program and the control group. Retrospective or prospective cohort designs were relatively frequent (n = 4; 44%; e.g., Lindholm-Leary, 2013; Morita-Mullaney et al., 2022; Nascimento, 2016), and pre-K and fifth grade were the minimum and maximum grades, respectively, across the reviewed studies. The remaining two studies that did not use group comparison (López & Tápanes, 2011; Lucero, 2018) used a developmental design in which the focus was the change in the children’s skills. Note, however, that the assessment occasions were relatively small; two time points in Lucero (2018) and three time points in López and Tápanes (2011).

It is important to make two caveats regarding studies with a repeated measures design. First, although two studies (Lucero, 2018; Serafini et al., 2022) described their research as longitudinal, their work examined the association or differences in the variable of interest between two distant time points; Lucero, for example, examined the differences in children’s oral discourse skills collected in kindergarten and second grade. Second, though some studies used a repeated measures design, only cross-sectional statistical analyses were used; for example, Nascimento (2016) used children’s data from kindergarten to third grade but used the t-test for group comparisons at each time point. While language and literacy skills were examined using all of the research designs described above, children’s knowledge of mathematics was examined in a single study using a pre–post test group comparison design (Barnett et al., 2007), and their behavior and cognitive and socio-emotional skills were examined in a different study using a retrospective cohort design (Serafini et al., 2022).

It is also noteworthy to mention that a small number of studies were also interested in the characteristics of children’s learning environments. The study conducted by López and Tápanes (2011) had a qualitative component in which caregivers completed phone and home interviews on their expectations, school engagement, cultural rearing practices, and home language and literacy environments. Moreover, only two studies examined the characteristics of instruction in pre-K classrooms. Barnett et al. (2007) and Oliva-Olson (2019) conducted a one-time observation in classrooms to evaluate instructional quality, classroom literacy environment, and practices to support children’s partner languages. The participating children from the first study attended 36 classrooms, and those from the second study attended 153 classrooms. The following sections provide information about these studies’ assessments and Table A1 provides this information per study.

3.3. DLE Programming

Despite the diversity of DLE described in the Introduction, the reviewed studies provide limited information on the implementation of these programs in the participating classrooms. For example, López and Tápanes (2011) focused on a two-way immersion program but did not specify the model (e.g., 50/50, 90/10). Of the remaining studies, three involved children who only experienced a program that utilized equal exposure to English and children’s partner languages in pre-K and/or K (i.e., 50/50; Barnett et al., 2007; Nascimento, 2016; Oliva-Olson, 2019), and five involved participants who were exposed to different programs, in which the least amount of instruction in the partner languages was 50% (Anderberg & Ruby, 2013; Lindholm-Leary, 2013; Lucero, 2018; Morita-Mullaney et al., 2022; Serafini et al., 2022).

Among the studies mentioned in the previous paragraph that reported the language model (n = 8, 89%), six described how English and children’s partner languages were used in the instruction. In two of the reviewed studies (Barnett et al., 2007; Nascimento, 2016), the languages alternated on a weekly basis. For example, in Barnett et al.’s study (2007), children rotated every week between two teacher teams; one teacher focused on English and another focused on Spanish. In the remaining four studies (Anderberg & Ruby, 2013; Lindholm-Leary, 2013; Lucero, 2018; Oliva-Olson, 2019), children were exposed on a daily basis to instruction in English and their partner languages. Though Lindholm-Leary (2013) did not provide this information about Sobrato Early Academic Literacy, the DLE program of interest, we used the information provided on the program’s website. Except for Anderberg and Ruby (2013), the authors reported that these languages were kept separate. For instance, in Lucero’s study, K–second grade students received literacy instruction in English and Spanish (partner language), but the math and science instruction was only in Spanish. Children were encouraged to use the target language. In Oliva-Olson’s study (2019), pre-K children were exposed to large- and small-group activities organized by language and teachers who modeled the target language. Although some studies described their DLE programs, only Anderberg and Ruby (2013) reported checking the fidelity of the programs.

It is important to note that among the six studies that involved students from different grades, two also reported how children’s exposure to the language models varied across grades. For example, for some participants in Lindholm-Leary’s study (2013) the proportion of time of exposure to Spanish progressively changed from 90% in K and first grade to 50% after fourth grade. Similarly, in Lucero’s study (2018), K through second grade students were taught math and science in Spanish. Starting in third grade, however, science instruction switched to English. Literacy instruction was always in Spanish and English. In the remaining studies, the language model was the same across grades (Morita-Mullaney et al., 2022; Nascimento, 2016) or the information was not explicitly reported (López & Tápanes, 2011; Serafini et al., 2022).

The information about the background of teachers and peers was also limited. Only three of the nine reviewed studies (33%) reported information on the language status of peers who attended the participating classrooms (Barnett et al., 2007; Lucero, 2018; Oliva-Olson, 2019). In Barnett et al.’s study (2007), for instance, the classrooms integrated children whose primary language was Spanish (57%), English (37%), or another language (5%). Although the remaining studies reported that the schools served a large number of bilingual children, they did not provide information about the participating classrooms’ composition. Regarding teachers’ backgrounds, only three reported that teachers received training to support bilingual children’s languages (Anderberg & Ruby, 2013; Lindholm-Leary, 2013; Morita-Mullaney et al., 2022).

3.4. Child Outcomes

All of the reviewed studies (n = 9) were interested in children’s language-related skills and assessed a wide spectrum of constructs. While four studies (44%; Lindholm-Leary, 2013; López & Tápanes, 2011; Morita-Mullaney et al., 2022; Serafini et al., 2022) focused only on children’s general language proficiency, others also focused on specific language systems or emergent literacy skills, such as vocabulary, phonological awareness, letter recognition, and print knowledge. Regarding the skills encompassed in writing and reading, which are frequently the target of interventions in early childhood, most of the studies focused on lower-level language skills, including vocabulary and letter recognition. One exception was the study conducted by Lucero (2018), who assessed macro-level elements of children’s oral and written narrations, including their ability to produce coherent, sequential, and detailed narratives. Seven of the nine studies (78%) assessed children’s language-related skills in their partner language, that is, Spanish, and/or English. The other two studies used only English assessments. Another noticeable characteristic of the reviewed literature is that some studies used assessments administered by states and schools to monitor whether children meet expected standards. Table A1 specifies the languages measured and instruments per study. For example, Serafini et al. (2022), who used data from the Miami School Readiness Project, analyzed students’ performance in the high-stakes Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test (FCAT), the Miami-Dade County Oral Language Proficiency Scale-Revised (M-DCOLPS-R), and the Comprehensive English Language Learning Assessment (CELLA). A few scholars designed assessment tasks to collect information on children’s outcomes, including Lucero (2018), who created an activity and used protocols to elicit and evaluate children’s narrations in their different languages. In this study, children were asked to retell a story after listening to researchers narrate the story using a wordless picture book (Lucero, 2018). The variety of instruments and evaluation metrics used in the studies selected for this review made it difficult to conduct a unified quantitative analysis of their findings.

Overall, the group-comparison studies suggested that DLE programs supported children’s language-related skills or showed that these programs’ influence was comparable with that of English-only programs. Nascimento (2016), Serafini et al. (2022), and Barnett et al. (2007), for example, reported that among bilinguals, those enrolled in TWI classrooms tended to outperform their peers in classrooms where the main language of instruction was English when their language and literacy skills were examined. In cases in which there was no group comparison, significant gains in children’s linguistic skills were documented, especially those in English. Lucero (2018), for instance, found that bilinguals’ narrations had significantly more English and Spanish words and unique words in second grade than in kindergarten. However, only their narrations in English were more cohesive, detailed, and complex in second grade than in kindergarten. It is important to interpret these results in the context of the studies’ limitations, some of which are mentioned in the Research Design subsection.

Only one study assessed students’ mathematics skills, such as their ability to analyze and solve mathematical problems. Barnett et al. (2007) compared students attending TWI programs with students attending English-only programs. This study assessed mathematics skills in English and Spanish during pre-K using the Woodcock–Johnson psycho-educational battery—revised (WJ-R; Woodcock & Johnson, 1989) and the Bateria Psico-Educativa Revisada de Woodcock–Muñoz-Revisada (WM-R; Woodcock & Muñoz-Sandoval, 1996). The authors reported that children’s mathematics skills increased from fall to spring of the same school year, but there were no differences between those enrolled in TWI and English-only programs.

3.5. Dual Language Classroom Practices

Two studies in pre-K classrooms included classroom observations in their study design. First, Barnett et al. (2007) reported conducting classroom observations to examine instruction quality and identify the language and literacy environment in the classrooms for all students, especially young bilingual children. The results of this study showed no significant differences between TWI bilingual programs and programs where only English was the language of instruction regarding the general instruction quality. However, there were significant differences between the TWI classrooms: teachers used Spanish more frequently and incorporated the children’s cultural background into their classroom more often in the Spanish-TWI classrooms. Second, Oliva-Olson (2019) compared two classroom models: (1) DLE (instruction is in English and the partner language) and (2) English with Home Language Support (EHLS; instruction is in English, and the partner language is only used if needed). The results of this study were surprising as they showed that the support for the partner language was lower in DLE classrooms than in EHLS classrooms. Furthermore, both types of classrooms were of high quality; however, the DLE classrooms scored significantly higher for the emotional support and instructional support subscales compared with EHLS classrooms.

The previous two studies used observational assessments that focused on global classroom quality and specific practices relevant to bilingual children. Regarding the first type of assessment, Barnett et al. (2007) used the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale—Revised (ECERS-R; Harms et al., 1998), which evaluates six subscales of structural and interaction processes in classrooms, such as interactions and space and furnishing. Barnett et al. (2007) also used the Supports for Early Literacy Assessment (SELA; Smith et al., 2001), which measures more nuanced characteristics of the classroom, including practices and resources to support vocabulary knowledge. Oliva-Olson (2019) used the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS; Pianta et al., 2008), which evaluates 11 dimensions focusing on characteristics of teacher–child interactions, like teacher sensitivity and behavior management. Barnett et al. (2007) and Oliva-Olson (2019) also evaluated how the instruction incorporated children’s heritage languages and cultures, including whether teachers used children’s partner languages and their use of effective strategies to support their English learning. To assess this, Barnett et al. (2007) used a set of items from the Supports for English Language Learners Classroom Assessment (SELLCA; NIEER, 2005), while Oliva-Olson used the Classroom Assessment of Supports for Emergent Bilingual Acquisition (CASEBA; Freedson et al., 2011).

3.6. Parents’ Perceptions of Dual Language Education

One mixed methods study emerged from our search focusing on parents’ perceptions of DLE. This study reported findings on parents’ reasons for choosing to enroll their children in a Spanish–English TWI program. Specifically, López and Tápanes (2011) found that parents reported that the goal of bilingualism for their children was a key motivator to enroll them in a TWI program. This motivation came from their observation of home language loss in their children by age 5. In this study, all mothers interviewed were Latinas.

4. Discussion

The number of early childhood programs and schools implementing DLE in the United States is growing, although these programs are still not being offered widely to respond to the educational needs of the increasingly linguistically diverse student population (Williams et al., 2023). Research supporting the design and implementation of this type of bilingual education program has largely focused on children in upper elementary and middle schools (ages 8–14) (e.g., Johnson, 2024; Watzinger-Tharp et al., 2016). The purpose of this systematic review of the research literature is to synthesize current knowledge that can inform early childhood equity-oriented policies and practices and to identify gaps to be addressed in future research on the early education of bilingual children. Across all of the studies reviewed, most studies examined language and literacy development, and two studies observed classrooms to examine the quality of the classroom environment. Only one study examined mathematical learning in either pre-K or kindergarten. There was a limited number of studies that also examined cognitive ability, executive function, and socio-emotional and behavioral skills, with only one study addressing each of these domains. Key findings, gaps, and future research needs are discussed in the following sections responding to the research questions.

4.1. What Is the State of Knowledge on DLE in Early Childhood (Pre-K and K) in the United States?

4.1.1. Language and Literacy Development Outcomes

Unsurprisingly, the most frequent educational outcomes of interest in the reviewed studies were language-related skills, from phonological awareness to writing skills. Despite the wide spectrum of linguistic outcomes, many studies on specific linguistic systems focused on word recognition and lower-level language skills, which represent automatic processes that support comprehension (Hogan et al., 2011), like vocabulary and grammar. The emphasis on word recognition and lower-level language skills has been documented in other literature reviews of pedagogical interventions that target literacy-related skills among young children (birth through age 5) from linguistically diverse backgrounds (e.g., Castro et al., 2011; Larson et al., 2020). Larson et al., for example, found that 78% of the 41 studies assessed children’s vocabulary, while a smaller number measured skills such as narrative discourse. Though solid word recognition and lower-language skills are essential for literacy development, higher-level language skills also assist one’s comprehension, and they develop from early childhood.

A small number of studies in this review examined bilinguals’ higher-level language skills, which allow us to create an integrated representation of the text as a whole, such as inference-making and comprehension monitoring, by assessing narrative skills. Note that another group of studies that mainly focused on school-age children holistically examined broad linguistic domains, including reading and writing, which require higher-level language skills. Given the strong association between early narrative skills and later reading comprehension, studying the narrative skills of bilingual children in the early years can help predict their future literacy abilities (Miller et al., 2006) and also their oral language and social pragmatic competence (Gutiérrez-Clellen, 2002; Tare & Gelman, 2010). Narrative skills start to emerge around 3 to 4 years of age, and development continues well into school age (Hickmann et al., 2015). In the present review, Lucero’s (2018) findings related to the narrative skills of bilingual children in K and second grade are consistent with that developmental progression. Similarly, Uccelli and Páez (2007) found significant gains in narrative skills in English and Spanish among bilingual children between K and first grade, although it is not specified in their study if the children were enrolled in any type of bilingual education program.

An overall asset of the reviewed literature is that, in the majority of the studies, the authors measured bilingual children’s learning in their two languages. This is consistent with current approaches that posit that bilingualism is a distinctive characteristic that permeates bilinguals’ developmental and social domains and that fair methods that acknowledge children’s abilities in their languages are important to understand their development (Byers-Heinlein et al., 2019; Castro, 2014; Luk, 2023; De Houwer, 2022). Yet, two aspects of the operationalization of language in the reviewed literature merit attention. First, in many cases, the operationalization of the outcomes was aligned to a categorical rather than a continuous model of bilingualism. Scholars tended to operationalize children’s languages as independent multidimensions, ignoring the dynamic nature of children’s linguistic abilities (Luk, 2023; De Houwer, 2022). For example, scholars used different groups to represent the language proficiency spectrum, such as English language learners vs. fluent English speakers vs. native English speakers. Furthermore, the use of unilingual tests was frequent. These methodological choices overlook the fact that bilinguals’ languages are active and interact in linguistic tasks (Bialystok et al., 2012), that their vocabulary knowledge is distributed between their languages (Oller et al., 2007), and that there is wide variation in individuals’ bilingual experiences that can be masked by creating those groups (De Houwer, 2022).

Second, some scholars used state and school instruments that were not developed to assess bilingual communicative repertoires but instead monolinguals’ skills. Consequently, monolingual standards were used to gauge bilinguals’ language proficiency, which can lead to unintended deficit-oriented conclusions and negative attitudes toward bilingualism that can influence real-life decisions (De Houwer, 2022). The challenges with English-only assessments of bilingual students have been extensively discussed in the research and policy literature (e.g., Escamilla et al., 2017; Ortiz et al., 2022). As stated by Ortiz et al. (2022) “Assessments yield accurate information about the abilities of emergent bilinguals only when they give students credit for what they know and can do in their native language, in English, and using translanguaging practices”.

The reviewed studies support the implementation of DLE education programs. Taking into consideration their methodological limitations (described in the next section), the authors concluded that DLE programs benefited bilinguals’ English skills more or as much as students who attended English-only programs, who were bilinguals and/or monolinguals. Importantly, some studies also showed that DLE programs can support children’s partner languages. These results coincide with previous systematic reviews of linguistically and culturally responsive interventions for young children (birth through age 5) from diverse language backgrounds (Hur et al., 2020; Larson et al., 2020). For example, Larson et al. (2020) documented that 22 of the 28 reviewed studies found positive effects of the interventions on children’s English language and literacy skills, and 18 of 23 studies that measured children’s partner languages also found positive effects. Nonetheless, the wide variability in the interventions’ effect sizes across the reviewed studies in Hur et al. (2020) and Larson et al. (2020) raises questions about the replicability of the results in different populations and the methodological limitations that could degrade the interventions’ effects.

4.1.2. Dual Language Classroom Practices

Long-standing research indicates that improving teaching practices for bilingual children in early childhood classrooms (i.e., bilingual culturally sustaining instruction and bilingual assessments, among others) increases the overall quality of the classroom experience and is thus beneficial for both bilingual and monolingual children (Buysse et al., 2014; Castro et al., 2017; Sembiante et al., 2022). However, only two studies reviewed included observations to examine classroom quality components and accessible and available language and literacy supports for young bilingual children attending DLE programs. Barnett et al. (2007) found that teachers in two-way immersion programs spoke Spanish more frequently and embedded children’s cultural background into their teaching strategies; however, Oliva-Olson (2019) showed no differences in classroom quality in DLE classrooms, as assessed with the CASEBA, when compared to classrooms where instruction is in English with home language support used if needed. The differences in the findings might be attributed to the limited information about how language is used (e.g., to provide instruction vs. to provide directions) and how much time each language is used in the classroom. Most of the studies included in this review did not provide information about the fidelity of implementation of the DLE programs, which should include an optimal linguistic environment of the classroom with an appropriate time allocation for each language. Future studies should carefully examine the classroom environment, including teacher pedagogical practices, language adherence to the partner language, the available language and literacy environment, and available activities for young bilingual children.

4.2. What Are the Gaps in Knowledge Related to DLE in the Early Years?

DLE has emerged as an asset-based model that values minoritized languages as children’s assets and thus promotes equitable opportunities for those students. However, the implementation of DLE confronts challenges. One challenge is the centrality of English proficiency as the ‘goal’ rather than a goal of bilingualism and biliteracy. A second challenge, and one that is evident in this present review, is that although the majority of studies included assessments of students’ abilities in both English and their LOTE, the findings were explained by their relation to students’ English abilities. Therefore, these studies are still sending the message that improved abilities in dominant American English matter more. A final challenge also found in the studies reviewed is that most state assessments of student’s grade level achievement were only conducted in English.

An important gap in current research is the absence of studies on DLE programs with partner languages other than Spanish. Specifically, in this review of research on DLE in the early years in the United States, none of the studies included children from Native nations attending DLE programs in their Indigenous languages and English, or Asian-American children attending DLE programs in an Asian language (e.g., Mandarin, Cantonese, or Vietnamese) and English. Also, very few studies included Black children (including African-Americans and Black children from other countries) who can be speakers of languages other than English (e.g., Haitian Creole), dialects, or vernaculars (i.e., African American English), and when they were included, the findings were not reported by race or ethnicity. The scarcity of research on DLE including children from racial and ethnic groups other than White and Latine seems to be an indication of the limited access that those populations of children have to the existing DLE programs, and the limited number of DLE programs available in languages other than Spanish and English, which has been discussed in the literature (Palmer, 2010; Carjuzaa & Ruff, 2016). Specifically, Black and Native students had almost no representation among the English-dominant students in the DLE programs involved in the studies reviewed. Understanding the limited access to DLE by non-White monolingual English-speaking students might also help understand the barriers and facilitators to promoting bilingualism among children of color in the United States.

It is also notable that many of the studies reported student participants’ language dominance but did not provide information about their race or ethnicity, which is restrictive for the interpretation of the results. For instance, Spanish-speaking students can be Black, White, Indigenous, or multiracial, just as English-speaking monolingual students can be Asian, Black, Latine, or White. Given the demographic diversity in the United States, and its history of discrimination of people of color (Solomon et al., 2019), it is relevant that DLE research recognizes the intersectionality among language, culture, race, and ethnicity.

4.3. What Are the Implications of Findings for Policy, Research, and Practice?

Research on the effects of DLE in the development and learning of young bilingual children should acknowledge the linguistic diversity of various communities to promote equity. All of the studies in this systematic review of DLE in the early years were conducted with bilingual children speaking Spanish (n = 9), but no consideration of the various Spanish dialects has been found in this review. Most studies referred to the children as Spanish speakers without providing information about their heritage countries, which can provide insight into and be a proxy for dialectal differences in Spanish. There are variations of Spanish that serve as dominant, such as Spanish from Spain occupying a higher status globally than varieties of Spanish across the diaspora where Spain colonized many indigenous and African people, resulting in those Spanish dialects from countries such as Cuba, Puerto Rico, or the Dominican Republic, which are countries with many Afro-Latinos, being deemed as lower quality.

Future research should investigate language policies that determine children’s eligibility and access to DLE programs by geographic area and socioeconomic status. This would uncover the educational system structures that perpetuate inequities in accessing educational opportunities for children from language and racial and ethnic-minoritized communities. More research is also needed to understand how young children and their families experience DLE, in particular, how they face the power relations that are inevitably present in these programs and what school administrators and teachers do to address them.

From policy and practice perspectives, expanding the number of DLE programs for 3- and 4-year-old children (and younger) would support these children’s development and learning as they transition into kindergarten. Promoting their bilingualism and biliteracy would not only positively affect their achievement but also their socioemotional development. An additional consideration is that the use of an anti-racist, culturally sustaining curriculum should be an intrinsic element of bilingual education programs for young bilingual children (Castro & Meek, 2022), such a curricular approach should have “as its explicit goal supporting multilingualism and multiculturalism in practice and perspective for students and teachers” (Paris, 2012).

4.4. Methodological Limitations

Several methodological limitations were found in the studies reviewed that deserve discussion because they affect the quality of the existing research body. We expect that identifying these limitations could inform the formulation of future research studies. There is inconsistent reporting of children’s language status; most studies did not report how children were identified as being bilingual (i.e., English learners or dual language learners) to be included in the study. In the few cases in which there was a procedure, it was based on teachers’ or parents’ reports. Similarly, information was not provided on how programs classified children as bilinguals (i.e., ELs or DLLs) to be placed in a DLE program. Differences in the use of terms to refer to student participants and the absence of descriptions of DLE programs’ characteristics make it difficult to generalize across studies. The small sample sizes in several of the quantitative studies also constitute a challenge for the generalization of results, power analyses were not reported in most studies. Furthermore, most of the quantitative studies were correlational and cross-sectional, and the studies using a longitudinal design, though some used a repeated measures design, only conducted cross-sectional statistical analyses. Furthermore, none of the studies in this review examined the fidelity of implementation for both language allocation and DLE instructional practices. Thus, it is not possible to determine whether teachers adhere to the proportion of use of the partner languages, and the quality of the DLE instructional practices cannot be established. It is concerning that many of the methodological limitations found in this systematic review of the research coincide with limitations found in previous systematic reviews of the research on the early care and education of bilingual children published a decade ago (Castro, 2014). The fields of developmental and education sciences should take these findings into consideration and take action to promote more scientifically sound research focusing on the development and learning of young bilingual children attending dual language education.

5. Conclusions

In this section, the main conclusions emerging from the review are highlighted:

- There is limited research on existing DLE in early childhood programs for children 3–5 years of age; however, findings from the studies reviewed show that DLE is beneficial overall for bilingual children in the minoritized partner language group, as well as for the English-speaking monolinguals, in terms of children’s language and literacy. Yet, there are some mixed findings that can be attributed to the limited number of studies found, the heterogeneity in constructs examined, and the assessment measures used across studies.

- Some progress has been observed in this review related to the reporting of children’s language and literacy outcomes in children’s two languages as compared with findings from previous systematic reviews (e.g., Castro, 2014). The majority of studies (seven out of nine) used parallel assessments in Spanish and English across all domains to assess students’ outcomes. Assessing children in both of their languages improves the validity of the research by allowing children the opportunity to demonstrate their full set of capabilities (Ortiz et al., 2022).

- More research is needed to understand the limited or lack of participation of children from Native nations, Black children, and children from other racial, ethnic, and diverse language backgrounds in DLE (Palmer, 2010; Carjuzaa & Ruff, 2016). Future DLE studies focused on these populations could increase understanding of the educational policies and practices that might be limiting their participation in DLE programs and research.

- In this review, we did not include qualitative studies. However, research using qualitative methodologies could help understand the complexities of interactions, perceptions, and beliefs of teachers, children, and families participating in dual language education programs (e.g., Chaparro, 2019) and the systems and structures that perpetuate inequities in the early education of bilingual children from linguistically minoritized communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C.C., X.F.-J. and L.J.C.-M.; Methodology, D.C.C., X.F.-J. and L.J.C.-M.; Formal analysis, D.C.C., X.F.-J. and L.J.C.-M.; Data curation, D.C.C., X.F.-J. and L.J.C.-M.; Writing—original draft, D.C.C., X.F.-J. and L.J.C.-M.; Writing—review & editing, D.C.C., X.F.-J. and L.J.C.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Claudia Pacheco for her assistance during the systematic literature search process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Description of research design elements and results of studies reviewed.

Table A1.

Description of research design elements and results of studies reviewed.

| Reference | Study Purpose | Study Design | Study Participants/Setting Characteristics | Outcome Measures/Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anderberg and Ruby (2013). | To examine the change in children’s receptive vocabulary after being exposed to different instructional models | Pre–post test natural groups design with three comparison groups. | N = 45 children. Ages 3–4 years old. The children were Spanish–English simultaneous or sequential English–Spanish bilinguals. | Receptive vocabulary (English and Spanish)

| Children showed significant gains in their English receptive vocabulary, but their Spanish receptive vocabulary was comparable in the pre- and post-test. |

| 2. Barnett et al. (2007). | To compare the effects of dual language or two-way immersion (TWI) and monolingual English immersion (EI) preschool education programs on children’s learning. | Pre–post test experimental design in which children were randomly assigned to DLE and control groups. | N = 131 students (79 in TWI and 52 in EI) from 36 classrooms. Ages 3–4 years old. TWI: 79% of the participants were Hispanic, 11% were African American, 6% were White/non-Hispanic, and 2% were other. EI: 73% of the participants were Hispanic, 15% were African American, 8% were White/non-Hispanic, and 2% were other. | Language and Literacy (English and Spanish)

| Children in both types of classrooms experienced substantial gains in language, literacy, and mathematics. No significant differences between treatment groups were found on English language measures. Among the native Spanish speakers, the TWI program produced large gains in Spanish vocabulary compared to the EI program. Both TWI and EI approaches boosted the learning and development of children, including ELL students, as judged by standard score gains. TWI improved the Spanish language development of English language learners (ELLs) and native English-speaking children without losses in English language learning. |

| 3. Lindholm-Leary (2013). | To understand the bilingual and biliteracy skills of Spanish-speaking, low-socioeconomic-status children who attended an English or bilingual program and examine whether their outcomes varied according to the instructional language and primary language proficiency. | Retrospective cohort design (from pre-K to second grade) with DLE and comparison groups. | N = 334 children 80 in kindergarten 138 in first grade 116 in second grade All were Hispanic and identified as English language learners at kindergarten entry. | Language and literacy outcomes (English and Spanish)

| At pre-K entry, children had relatively low proficiency in Spanish and English. Though many of them showed significant gains through the school years, they had, on average, low proficiency. Children enrolled in bilingual programs at pre-K showed similar or significantly lower performance in Spanish Pre-LAS than peers enrolled in English programs at pre-K, probably because the latter group was in a bilingual program in subsequent years. Children’s English skills were relatively comparable between those who attended bilingual and English programs at pre-K. Children who were more proficient in Spanish showed more English gains than their peers with limited Spanish. |

| 4. López and Tápanes (2011). | To examine families’ decisions to enroll their children in a Spanish–English differentiated TWI program and the language abilities of Latino children. | Mixed-methods approach: Three-time point developmental design (from pre-K to first grade) and family interviews (at pre-K) | N = 9 children and 8 mothers. The families were from Latino backgrounds. Age: 4.96 years old (end of pre-K year). | Early Literacy Home Environments (Parents):

| Parents reported that bilingualism is a key motivator to enroll their children in immersion programs. Parents reported that by age 5, they were observing language loss in their children. All children placed on the Spanish-dominant side of the program improved, with five of the seven children reaching fluent or advanced levels of proficiency when compared to monolingual speakers. These scores indicate that these bilingual children have language skills similar to monolingual speakers in at least one, if not both, of their languages. |

| 5. Lucero (2018). | To investigate the development of oral narrative retell proficiency among Spanish–English emergent bilingual children longitudinally from K to second grade in Spanish and English as they learned literacy in the two languages concurrently. | Two-time point developmental design (from K to second grade). | N = 12 students. The children were Spanish–English emergent bilinguals. Ages 4–7 years old. Assessed in K and second grade children. The researchers did not explicitly mention the children’s race/ethnicity. | Language (English and Spanish)

| Significant improvement in vocabulary in both languages. Overall story structure improved only in English, suggesting that discourse skills were facilitated, and in Spanish, discourse was stagnant even with dual immersion programs. |

| 6. Morita-Mullaney et al. (2022). | To examine the influence of children’s demographics, time, teachers’ characteristics, and language model on children’s Spanish skills. | Prospective cohort design (from K to fourth grade) with DLE and comparison groups. Propensity score matching was used to compare groups. | N = 94 emergent bilinguals, all native Spanish speakers enrolled in kindergarten. The researchers did not explicitly mention the children’s race/ethnicity. N = 18 teachers. | Listening, speaking, reading, and writing (Spanish)

| The amount of variability explained by child and teacher characteristics and time varied across the linguistic systems. The predictive value of child and teacher variables and language model also varied across the linguistic systems. (i.e., students enrolled in a 90/10 program—90% in Spanish and 10% in English—scored higher in the writing assessment than those enrolled in a 50/50 program). |

| 7. Nascimento (2016). | To compare overall academic achievement in the area of language arts literacy among elementary bilingual students enrolled in either a dual language, tTWI program or in an early exit, transitional bilingual program in a large urban public school district. | Retrospective cohort design (from kindergarten to third grade) with DLE and comparison groups. | N = 23 Spanish–English bilingual students enrolled continuously in one school from K to third grade. 9 students were enrolled in a dual language program. 14 students were enrolled in a transitional bilingual program. The researchers did not explicitly mention the children’s race/ethnicity | Language proficiency and Literacy (English)

| Students continuously enrolled in a dual language, tTWI exhibited higher academic achievements than students enrolled in early exit transitional bilingual programs consistently across kindergarten to third grade. Students enrolled in the early exit transitional bilingual program during K exhibited higher scores than the students enrolled in the TWI only as measured using the Ohio Word Test. |

| 8. Oliva-Olson (2019). | To compare classroom quality and improvements in children’s language skills for programs implementing two Head Start classroom language models: (1) A dual language model and (2) English with home language support (EHLS). | Pre–post test natural groups design with DLE and comparison groups. | N = 841 students. Age: 3–4 years old. The researchers did not explicitly mention the children’s race/ethnicity. The children’s classrooms had a large proportion of DLLs whose home language was Spanish. | Language Proficiency (English and Spanish)

| Relative to EHLS, dual language classrooms scored, on average, lower in CASEBA but higher for emotional support and instructional support. The dual language model appeared to be more effective than the EHLS model in improving both English language and Spanish language development. |

| 9. Serafini et al. (2022). | To assess the long-term linguistic and academic outcomes associated with different bilingual language education models for low-income dual language learners (DLLs) residing in a bilingual, bicultural context. | Retrospective cohort design (from pre-K to fifth grade) with DLE and comparison groups. | N = 18,588 students. The children were enrolled in different education programs from re-K to fifth grade. 85.8% of children were Hispanic/Latino, 3.9% were White/Asian/other, and 10.4% were African American/Black/Caribbean. | Language Proficiency (English)

| Students not in poverty, with fewer behavioral issues in pre-K, and those who exited ESOL earlier showed stronger academic performance in all outcomes. Bilingual, rather than monolingual, forms of instruction were associated with acquiring English faster and superior performance in all measures of fifth grade academic achievement. There was faster English acquisition for DLLs in two-way immersion programs. |

Note

| 1 | We use the term “Latine” as a gender-inclusive term to refer to people of Latin American descent in the United States. |

References

- American Councils Research Center (ARC). (2021). 2021 Canvass of dual language and immersion (DLI) programs in U.S. public schools. American Councils Research Center (ARC). [Google Scholar]

- Anderberg, A., & Ruby, M. M. (2013). PRESCHOOL BILINGUAL Learners’ Receptive Vocabulary Development in School Readiness Programs. NABE Journal of Research and Practice, 4, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, M. B., & Fee, M. (2018). Recent research on the three goals of dual language education. In M. B. Arias, & M. Fee (Eds.), Profiles of dual language education in the 21st century (pp. 3–19). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C., & Wright, W. (2021). Types of education for bilingual students. In Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (7th ed.). Chapter 10. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D. L., Basaraba, D. L., & Polanco, P. (2016). Connecting the present to the past: Furthering the research on bilingual education and bilingualism. Review of Research in Education, 40, 821–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, W. S., Yarosz, D. J., Thomas, J., Jung, K., & Blanco, D. (2007). Two-way and monolingual English immersion in preschool education: An experimental comparison. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(3), 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I. M., & Luk, G. (2012). Bilingualism: Consequences for mind and brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(4), 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse, V., Peisner-Feinberg, E., Páez, M., Hammer, C. S., & Knowles, M. (2014). Effects of early education programs and practices on the development and learning of dual language learners: A review of the literature. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 765–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers-Heinlein, K., Esposito, A. G., Winsler, A., Marian, V., Castro, D. C., & Luk, G. (2019). The case for measuring and reporting bilingualism in developmental research. Collabra: Psychology, 5(1), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carjuzaa, J., & Ruff, W. G. (2016). American Indian English Language Learners: Misunderstood and under-served. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D. C. (2014). The development and early care and education of dual language learners: Establishing the state of knowledge. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D. C., & Meek, S. (2022). Beyond Castañeda and the “language barrier” ideology: Young children and their right to bilingualism. Language Policy, 21, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D. C., Espinosa, L., & Páez, M. M. (2011). Defining and measuring quality in early childhood practices that promote dual language learners’ development and learning. In M. Zaslow, I. Martinez-Beck, K. Tout, & T. Halle (Eds.), Quality measurement in early childhood settings (pp. 257–280). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, D. C., Gillanders, C., Franco, X., Bryant, D. M., Zepeda, M., Willoughby, M. T., & Mendez, L. I. (2017). Early education of dual language learners: An efficacy study of the Nuestros Niños School Readiness professional development program. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 40, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D. C., Gillanders, C., LaForett, D., Prishker, N., Garcia, E. E., Espinosa, L., Genesee, F., Hammer, C. S., & Peisner-Feinberg, E. (2024). A conceptual framework for advancing knowledge on the development of young bilingual children. [Unpublished manuscript].

- Chaparro, S. E. (2019). But mom! I’m not a Spanish Boy: Raciolinguistic socialization in a Two-Way Immersion bilingual program. Linguistics, and Education, 50, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, C. G., Crnic, K., Lamberty, G., Wasik, B. H., Jenkins, R., Garcia, H. V., & McAdoo, H. P. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, A. (2022). The danger of bilingual–monolingual comparisons in applied psycholinguistic research. Applied Psycholinguistics, 44, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla, K., Butvilofsky, S., & Hopewell, S. (2017). What gets lost when english-only writing assessment is used to assess writing proficiency in spanish-english emerging bilingual learners? International Multilingual Research Journal, 12(4), 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedson, M., Figueras-Daniel, A., Frede, E., Jung, K., & Sideris, J. (2011). The classroom assessment of supports for emergent bilingual acquisition: Psychometric properties and key initial findings from New Jersey’s abbott preschool program. In C. Howes, J. Downer, & R. Pianta (Eds.), Dual language learners in the early childhood classroom. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Gándara, P., & Escamilla, K. (2017). Bilingual education in the United States. In O. García, A. M. Y. Lin, & S. May (Eds.), Bilingual and multilingual education (pp. 439–452). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, L., Freeman, D., & Freeman, Y. (2005). Dual language education: A promising 50–50 model. Bilingual Research Journal, 29(1), 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Clellen, V. (2002). Narratives in two languages: Assessing performance of bilingual children. Linguistics and Education, 13, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, T., Clifford, R., & Cryer, D. (1998). Early childhood environmental rating scale-revised. Teacher’s College Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, S., Yang, L., Leung, G., Zhou, Q., Tong, R., & Uchikoshi, Y. (2021). Language proficiency and competence: Upper elementary students in a Dual-Language Bilingual Education program. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 43, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickmann, M., Schimke, S., & Colonna, S. (2015). From early to late mastery of reference: Multifunctionality and linguistic diversity. In The acquisition of reference (pp. 181–211). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, T., Bridges, M. S., Justice, L. M., & Cain, K. (2011). Increasing higher level language skills to improve reading comprehension. Focus on Exceptional Children, 44, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J. H., Snyder, P., & Reichow, B. (2020). Systematic review of English early literacy interventions for children who are dual language learners. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 40(1), 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A. (2024). Dual language education and academic growth. Teachers College Record, 126(2), 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A. L., Cycyk, L. M., Carta, J. J., Hammer, C. S., Baralt, M., Uchikoshi, Y., An, Z. G., & Wood, C. (2020). A systematic review of language-focused interventions for young children from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 50, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm-Leary, K. (2013). Bilingual and biliteracy skills in young Spanish-speaking low-SES children: Impact of instructional language and primary language proficiency. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 17, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L., & Tápanes, V. (2011). Latino children attending a two-way immersion program in the United States: A comparative case analysis. Bilingual Research Journal, 34(2), 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, A. (2018). The development of bilingual narrative retelling among Spanish–English dual language learners over two years. Language, Speech & Hearing Services in Schools, 49(3), 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, G. (2023). Justice and equity for whom? Reframing research on the “bilingual (dis) advantage”. Applied Psycholinguistics, 44(3), 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. F., Heilmann, J., Nockerts, A., Iglesias, A., Fabiano, L., & Francis, D. J. (2006). Oral language and reading in bilingual children. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 21, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, C. (2024). Dual language immersion programs and student achievement in early elementary grades. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita-Mullaney, T., Renn, J., & Chiu, M. M. (2022). Spanish language proficiency in dual language and English as a second language models: The impact of model, time, teacher, and student on Spanish language development. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(10), 3888–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, F. (2016). Benefits of dual language immersion on the academic achievement of English language learners. The International Journal of Literacies, 24(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). Promoting the educational success of children and youth learning English: Promising futures. The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2022). English learners in public schools. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- National Center on Cultural and Linguistic Responsiveness (NCCLR). (2015). Classroom language models: A leader’s implementation manual. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start. Available online: https://csaa.wested.org/resource/classroom-language-models-a-leaders-implementation-manual/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER). (2005). Support for English language learners classroom assessment. National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER). [Google Scholar]

- Oliva-Olson, C. (2019). Dos metodos: Two classroom language models in Head Start. Urban Institute. Available online: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/dos-metodos-two-classroom-language-models-head-start (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Oller, D., Pearson, B., & Cobo-Lewis, A. (2007). Profile effects in early bilingual language and literacy. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28(2), 191–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, A. A., Fránquiz, M. E., & Lara, G. P. (2022). Educational equity for emergent bilinguals: What’s wrong with this picture? Bilingual Research Journal, 45(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D. (2010). Race, power, and equity in a multiethnic urban elementary school with a dual-language “strand” program. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 41, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M., O’Toole, A., & Katsiaficas, K. (2017). Dual language learners: A national demographic and policy profile. Migration Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta, R. C., La Paro, K. M., & Hamre, B. (2008). Classroom assessment scoring system: Dimensions overview. Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Arroyo, S., & Pearson, F. (2020). Learning from the history of language oppression: Educators as agents of language justice. Journal of Curriculum, Teaching, Learning and Leadership in Education, 5(1), 28–37. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/ctlle/vol5/iss1/3/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Sembiante, S. F., Yeomans-Maldonado, G., Johanson, M., & Justice, L. (2022). How the amount of teacher Spanish use interacts with classroom quality to support English/Spanish DLLs’ vocabulary. Early Education and Development, 34(2), 506–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, E. J., Rozell, N., & Winsler, A. (2022). Academic and English language outcomes for DLLs as a function of school bilingual education model: The role of two-way immersion and home language support. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(2), 552–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S., Davidson, S., Weisenfeld, G., & Katsaros, S. (2001). Supports for early literacy assessment (SELA). New York University. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, D., Maxwell, C., & Castro, A. (2019). Systemic inequality and American democracy. Center for American Progress. [Google Scholar]

- Tare, M., & Gelman, S. A. (2010). Can you say it another way? Cognitive factors in bilingual children’s pragmatic language skills. Journal of Cognitive Development, 11(2), 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccelli, P., & Páez, M. M. (2007). Narrative and vocabulary development of bilingual children from kindergarten to first grade: Developmental changes and associations among English and Spanish skills. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 38(3), 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K., & Dinkes, R. (2020, June 10). Bar chart races: Changing demographics in K–12 public school enrollment. NCES Blog. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/learn/blog/bar-chart-races-changing-demographics-k-12-public-school-enrollment (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Watzinger-Tharp, J., Swenson, K., & Mayne, Z. (2016). Academic achievement of students in dual language immersion. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(8), 913–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. P., Meek, S., Marcus, M., & Zabala, J. (2023). Ensuring equitable access to dual-language immersion programs: Supporting English learners’ emerging bilingualism. The Century Foundation and The Children’s Equity Project. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, R., & Johnson, M. (1989). Woodcock-Johnson psycho-educational battery-revised. DLM Teaching Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, R., & Muñoz-Sandoval, A. F. (1996). Bateria woodcock-munoz: Pruebas de habilidad cognitive-revisada. Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).