Measuring Reflective Inquiry in Professional Learning Networks: A Conceptual Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- How can reflective inquiry in conversations within PLNs be measured?

- -

- How can AI be used to support this measurement approach?

- -

- What insight does this measurement approach provide about the different types of reflective inquiry occurring in PLNs?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Reflective Inquiry in Professional Learning Networks

2.2. Observing Reflective Inquiry

2.2.1. The Degree of Collaborative and Dialogic Process (C)

2.2.2. The Degree of Generating and/or Testing Ideas Based on Multiple Data Sources (D)

2.2.3. Degree of Reflection and Internal Attribution (R)

2.2.4. Towards a Framework for Reflective Inquiry

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Degree of Collaborative Dialogue

- Speaker I:

- The professionalization days are focused on that as well. Everyone comes together: all first-grade teachers, all second-grade teachers, and so on, to exchange ideas. (C1)

- Speaker R1:

- That’s really nice. (C1)

- Speaker R2:

- That’s not how it works in our school cluster. (C1)

- Speaker R3:

- Same here. (C1)

- Speaker R2:

- Even with sharing resources, there are still schools who say, “No, this is specific to our school”. I think that’s nonsense. (C1)

- Speaker I:

- We’ve been working on it, and it gets a bit clearer every year, which is nice. But about mathematising, so that’s turning something into a math problem, and demathematising, is taking it away from math. That’s what I think those two words mean. Like turning Dutch into math or turning math into Dutch. Isn’t that it? What do you think? (C2)

- Speaker R1:

- That’s what it means. And do you do that with all your mathematical problems too? (C2)

- Speaker I:

- Yes, we look for solution strategies to solve certain real-life problems. (C1)

- Speaker R1:

- And those solution strategies, have you given them specific names? (C2)

- [...]

- Speaker R2:

- Maybe with a “problem of the week,” you could offer problems at varying levels of difficulty. (C2)

- Speaker R1:

- [...] That’s why I’d propose having a core knowledge test at the start or end of each trimester. A few per semester would clearly show where they stand. (C2)

- Speaker R2:

- You’d miss the point of core knowledge. For example, if it’s about triangles, core knowledge only covers naming the triangles. Then it’s no longer core knowledge—it’s just studying. It’s more useful to say, “With Pythagoras, you get a relationship, but what was it again?” It’s meant to build on or recall what they’ve seen before. Otherwise, it’s just a prerequisite knowledge test. (C3)

4.2. The Degree of Generating and/or Testing Ideas Based on Multiple Sources

- Speaker R1:

- You experience these difficulties during the meeting. Do you ask questions, or do you run into your own lack of motivation? (D1)

- Speaker I:

- I find the most tiring thing to keep convincing others about it. They are so quick to say: “I need special needs assistance, or there needs to be a diagnosis”. They want to forget the phases before that and go straight to the third phase of IEP. (D1)

- Speaker R2:

- Or they rely on you as the special needs coordinator. (D1)

- Speaker I:

- I also got the question last week. I thought it was a good meeting in itself—it was a meeting with the second preschooler’s teacher who has resistance, and I just clearly sent an email on the needed preparation. If nothing comes... I mainly bump into the teachers who have never had anything to say, but then the kids are in the third preschool, and it’s just “they didn’t see that in the previous year,” so there was a gap in that. So I’ve started this school year by telling them very clearly that when it’s time to consult, you get ready, you make an overview about the kids, and you tell me if there is a child you want to discuss at the meeting. I’ve told them, and I’m noticing a slight change. (D1)

I’m someone who also likes to do it for myself, too. As a teacher, you check the goals you want to achieve with your students, and as a special needs coordinator, I also want to check my goals for myself. I check my <evidence based> roles, I want to monitor myself with the number of hours I have, 32 out of 36, I personally think that’s achievable, and that I should strive for that. So I created a template for myself with those <evidence based> roles and their explanations in it, and once a month, at the end of the month, I’ll take my agenda and I’m going to tout for myself: that task includes that role, that task with that role. In such a way that I see: I did not uptake that role much at the moment, or I have not covered that much, that I can check why? Was there a question or is that something I’ve lost sight of?

4.3. Degree of Reflection and Internal Attribution

Yes, I think for myself, because I’ve only been a special needs coordinator for a few months, it’s still difficult to ask the right questions to them like that. Certain things that make me wonder, we have a mentor and when I hear her asking questions, when she afterwards discusses them with us, that I think yes, sure, those are the most logical questions. But I won’t figure that out myself, I’m still early in my career, I still need to learn how to ask the right questions.

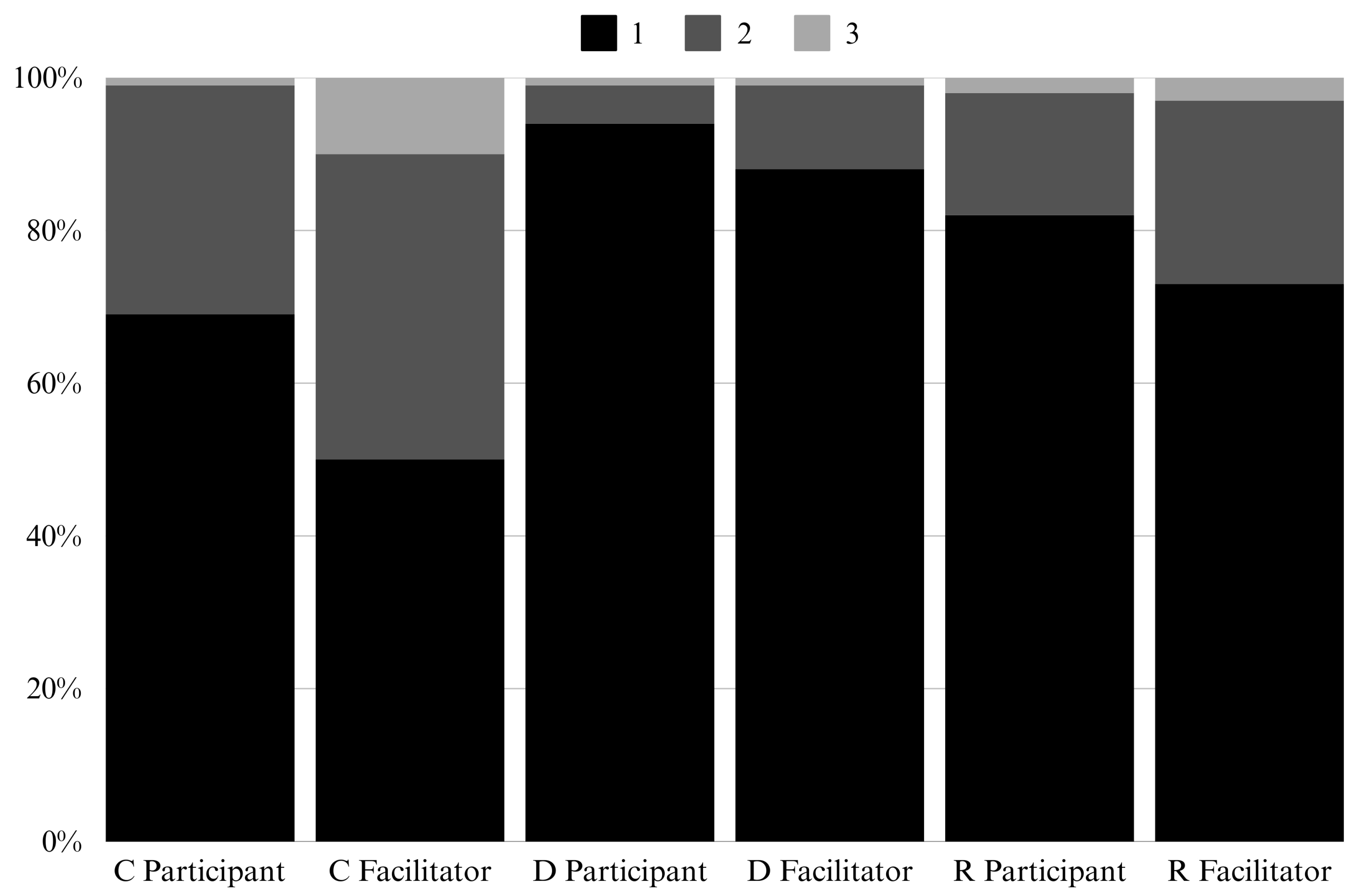

4.4. Occurrence of Reflective Inquiry

- Speaker R:

- That’s also problematic for a school if no one can handle the data. You must be able to work with data literacy—you need to work with standard deviation, boxplots, and the information they provide. (C2, D2, R2)

- Speaker I:

- In <learning platform>, there’s a possibility to work with data, but apparently, that wasn’t purchased. And among the staff, there’s no data analyst either. (C1, D1, R1)

- Speaker R:

- You should definitely look for colleagues willing to help. This will also support realizing this initiative. If you can convince people with data, you’ll take a step forward. Who do we want to convince? We all want to win over subject teachers. Subject teachers are not language teachers. They think differently, work differently, and want numbers, and numbers can be persuasive. So show them. For example, “We started with zero books; students had never read a book before. Now it’s 27 books”. And this is reflected in math results. If you can demonstrate that, you’ve done excellent work, really. Let me check, I printed it out for you. This comes from ‘The Reading Scan.’ Did you also conduct this with your school? I believe you did some time ago. This aspect of the reading policy plan is critical for expanding it across the school. But the key question remains: How often are you reading? That’s where we need to start. From there, we won’t convince teachers if we say, “We read twice a week and have a few results, but they’re not really convincing”. That creates a vicious cycle. (C3, D3, R3).

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PLN | professional learning network |

| PLC | professional learning community |

References

- Alzayed, Z. A., & Alabdulkareem, R. H. (2020). Enhancing cognitive presence in teachers’ professional learning communities via reflective practice. Journal of Education for Teaching International Research and Pedagogy, 47(1), 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, S. D. (1995). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C., & Poortman, C. (2018). Networks for Learning: Effective collaboration for teacher, school and system improvement (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C., Poortman, C., Gray, H., Ophoff, J. G., & Wharf, M. (2021). Facilitating collaborative reflective inquiry amongst teachers: What do we currently know? International Journal of Educational Research, 105, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charteris, J., & Smardon, D. (2014). Dialogic peer coaching as teacher leadership for professional inquiry. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 3(2), 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampa, K., & Gallagher, T. L. (2016). Teacher collaborative inquiry in the context of literacy education: Examining the effects on teacher self-efficacy, instructional and assessment practices. Teachers and Teaching, 22(7), 858–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keijzer, H., Jacobs, G., Van Swet, J., & Veugelers, W. (2020). Identifying coaching approaches that enable teachers’ moral learning in professional learning communities. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 9(4), 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1910). How we think. Available online: https://pure.mpg.de/pubman/item/item_2316308_3/component/file_2316307/Dewey_1910_How_we_think.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Doğan, S., & Adams, A. (2018). Effect of professional learning communities on teachers and students: Reporting updated results and raising questions about research design. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 29(4), 634–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, L. M., & Timperley, H. (2008). Professional Learning Conversations: Challenges in using evidence for improvement. In Springer eBooks. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dib, M. a. B. (2006). Levels of reflection in action research. An overview and an assessment tool. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(1), 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley-Ripple, E., May, H., Karpyn, A., Tilley, K., & McDonough, K. (2018). Rethinking connections between research and practice in education: A conceptual framework. Educational Researcher, 47(4), 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhnia, M., Banihashem, S. K., Noroozi, O., & Wals, A. (2023). A SWOT analysis of ChatGPT: Implications for educational practice and research. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 61(3), 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher-Yoshida, B., & Yoshida, R. (2022). Transformative learning and its relevance to coaching. In Springer eBooks (pp. 935–948). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2005). How many interviews are enough? Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkarainen, K., Palonen, T., Paavola, S., & Lehtinen, E. (2004). Communities of networked expertise: Professional and educational perspectives. Available online: http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB05229407 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., & Marconi, V. C. (2016). Code saturation versus meaning saturation. Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jay, J. K., & Johnson, K. L. (2002). Capturing complexity: A typology of reflective practice for teacher education. Teaching And Teacher Education, 18(1), 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S., & Dack, L. A. (2013). Towards a culture of inquiry for data use in schools: Breaking down professional learning barriers through intentional interruption. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 42, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S., & Earl, L. (2010). Learning about networked learning communities. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 21(1), 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S., Earl, L., & Jaafar, S. (2009). Building and connecting learning communities: The power of networks for school improvement. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, A. (2023). Can ChatGPT and bard generate aligned assessment items? A reliability analysis against human performance. arXiv, arXiv:2304.05372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintz, T., Lane, J., Gotwals, A., & Cisterna, D. (2015). Professional development at the local level: Necessary and sufficient conditions for critical colleagueship. Teaching and Teacher Education, 51, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh, L. P. (2015). Teachers talking about teaching and school: Collaboration and reflective practice via Critical Friends Groups. Teachers and Teaching, 22(3), 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, J. W. (1990). The persistence of privacy: Autonomy and initiative in teachers’ professional relations. Teachers College Record the Voice of Scholarship in Education, 91(4), 509–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., Zhang, S., Wang, Q., & Chen, W. (2017). Mining online discussion data for understanding teachers reflective thinking. IEEE Transactions On Learning Technologies, 11(2), 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi, G., Balzano, M., & Marchiori, D. (2024). K-Alpha Calculator–Krippendorff’s Alpha Calculator: A user-friendly tool for computing Krippendorff’s Alpha inter-rater reliability coefficient. MethodsX, 12, 102545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C., & Sackney, L. (2011). Profound improvement: Building capacity for a learning community. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Murugaiah, P., Azman, H., Thang, S. M., & Krish, P. (2012). Teacher learning via communities of practice: A Malaysian case study. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 7(2), 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2015). Education policy outlook 2015: Making reforms happen. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortman, C. L., Brown, C., & Schildkamp, K. (2022). Professional learning networks: A conceptual model and research opportunities. Educational Research, 64(1), 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón-Gallardo, S., & Fullan, M. (2016). Essential features of effective networks in education. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 1(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J., & Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, C. (2002). Defining reflection: Another look at John Dewey and reflective thinking. Teachers College Record The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 104(4), 842–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J., Tan, S., & Tan, S. (2023). ChatGPT: Bullshit spewer or the end of traditional assessments in higher education? Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 6(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkamp, K., & Datnow, A. (2020). When data teams struggle: Learning from less successful data use efforts. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 21(2), 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, A. (Ed.). (2012). Preparing teachers and developing school leaders for the 21st century: Lessons from around the world. International Summit on the Teaching Profession. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. Available online: http://psycnet.apa.org/record/1987-97655-000 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Stoll, L. (2015). Using evidence, learning and the role of professional learning communities. In C. Brown (Ed.), Leading the use of research and evidence in schools (1st ed., pp. 54–65). IOE Press. [Google Scholar]

- Theelen, H., Vreuls, J., & Rutten, J. (2024). Doing research with help from ChatGPT: Promising examples for coding and Inter-Rater reliability. International Journal of Technology in Education, 7(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanblaere, B., & Devos, G. (2016). Exploring the link between experienced teachers’ learning outcomes and individual and professional learning community characteristics. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 27(2), 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K., Dochy, F., Raes, E., & Kyndt, E. (2015). Teacher collaboration: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 15, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Manen, M. (1977). Linking ways of knowing with ways of being practical. Curriculum Inquiry, 6(3), 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkington, J., Christensen, H. P., & Kock, H. (2001). Developing critical reflection as a part of teaching training and teaching practice. European Journal of Engineering Education, 26(4), 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmoes, A., Decabooter, I., Struyven, K., & Consuegra, E. (2025). Exploring learning outcomes: The impact of professional learning networks on members, schools, and students. School Effectiveness And School Improvement, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York-Barr, J., Sommers, W. A., Ghere, G. S., & Montie, J. (2016). Reflective practice for renewing schools: An action guide for educators. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

| Aspect | Collective Dialogue (C) | Data Sources (D) | Reflection (R) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus | Interaction | Use of multiple data sources | Individual depth of reflection |

| Observation | Degree of questioning and engagement | Degree of integration and triangulation of sources | Depth of reasoning and attribution |

| Speaker | Degree of Collective Dialogue (C) | Degree of Use of Multiple Data Sources (D) | Depth of Reflection (R) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initiating | The speaker shares contributions without inviting further engagement. | The speaker relies on personal experiences. | The speakers’ contribution consists of descriptive information. |

| Responding | The speaker acknowledges others’ contributions or shares their own contribution. | The speaker agrees or expands on others’ contributions with personal experiences. | The speaker acknowledges or expands on others’ contributions with descriptive information. | |

| 2 | Initiating | The speaker shares contributions and invites input. | The speaker relies mainly on personal experiences but references an additional data source. | The speakers’ contribution offers explanations or rationale but relies mostly on external attribution. |

| Responding | The speaker engages with others’ contributions by asking clarifying questions and/or offering suggestions. | The speaker expands on others’ contributions by referencing an additional data source. | The speaker offers reasons or explanations for others’ contributions. | |

| 3 | Initiating | The speaker shares contributions while asking probing questions to provoke critical dialogue and explore assumptions or actions collectively. | The speaker integrates a balanced use of multiple data sources. | The speaker critically reflects on their contribution, offering internally attributed explanations and questioning their role in a situation. |

| Responding | The speaker builds on others’ contributions with probing questions, critiques, or challenges assumptions. | The speaker expands on others’ contributions by triangulating multiple sources. | The speaker critically reflects on others’ contributions, offering explanations with internal attributions questioning others’ role in a situation. |

| PLN | Segment | # Minutes |

|---|---|---|

| PLN 1 | Segment 1 | 41 |

| Segment 2 | 42 | |

| Segment 3 | 51 | |

| PLN 2 | Segment 4 | 80 |

| Segment 5 | 68 | |

| Segment 6 | 69 | |

| PLN 3 | Segment 7 | 30 |

| Segment 8 | 30 | |

| Segment 9 | 119 | |

| Total | n = 9 | 530 min (8.84 h) |

| Speaker | Contribution | C | D | R | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Yeah, the big problem with those kids is that many of them don’t even have a book. They may have seen a book from a distance once. Before the last lesson, I even brought one of my own books because I felt like, if I use books... <deleted personal information> Uh, I had brought some books from her kindergarten class, and even those were difficult for them to read. So let alone if I were to use the chemistry book. | 1 | 1 | 1 | The speaker describes a personal experience descriptively without asking questions to facilitate the conversation (C1). The contribution relies on personal experience (“They may have seen a book from a distance once”). No other data sources are referenced (D1). The reflection is descriptive, without analyzing underlying reasons or implications (“I had brought some books from her kindergarten class, and even those were difficult for them to read”) (R1). |

| R | It’s a challenging audience. But even so, we shouldn’t let ourselves be guided by the level they’re currently at. We really need to aim higher, and that can actually spark their interest as well. | 2 | 1 | 2 | The responder engages with the initiator’s ideas by adding a different perspective (“We shouldn’t let ourselves be guided by the level they’re currently at”). The perspective is suggestive (C2) rather than confrontational (C3). The statement is based on a general principle (‘we really need to aim higher’). They do not reference other data sources (D1). The responder acknowledges a need for change and provides a rationale (“that can actually spark their interest as well”) (R2). |

| I | But that’s exactly it, yeah. So I hope to see some progress there, but I’m already getting the reaction, ‘Is it reading again?’ But we’re working on that. | 1 | 1 | 1 | The contribution acknowledges the responder’s comment but there are no questions to facilitate the conversation (C1). The speaker uses personal experiences, such as student reactions (“is it reading again?”) without referencing additional sources (D1). The contribution is descriptive, without analyzing or critiquing their approach (R1). |

| R | But how did you approach all the reading lessons? Have you really already done that by reading aloud according to the theoretical principles? Or was it just free reading? | 2 | 2 | 1 | The responder asks clarifying questions to gather more context (“But how did you approach all the reading lessons?”) (C2). The responder references theoretical principles as a source, suggesting a more structured approach to reading (D2). However, they do not triangulate across multiple sources or provide specific evidence (D3). The contribution gives not an explicit rationale or reasoning for the questions (R1). |

| I | Read freely, and they had to read that for themselves and then read out loud. | 1 | 1 | 1 | This statement is an answer to the question but does not invite further dialogue (C1). The contribution relies only on personal observations (D1). The statement is descriptive, recounting what was done during the lesson (“Read freely, and they had to read that for themselves”) (R1). |

| R | I think that might still be a step too far for them because they don’t enjoy reading themselves yet. If you enjoy reading, you’ll naturally share that enthusiasm, and you saw <anonymized> do that earlier—it’s a completely different approach. So I really think you need to focus on implementing <reading programme> because there’s an entire pedagogy behind it that changes how you approach reading. It’s much more than just saying, ‘We have to read for fifteen minutes,’ and it takes a completely different approach. | 3 | 2 | 3 | The responder challenges the practice (“I think that might still be a step too far for them”) (C3) emphasizing the need to focus on implementing <reading programme> and contrasting it with a surface-level approach (“It’s much more than just saying, ‘We have to read for fifteen minutes.’”). The responder references an evidence-based reading programme. However, it is a standalone source (D2), without integration of other sources (D3). The statement gives rationale (“because they don’t enjoy reading themselves yet.”) and critiques the current practice (“It’s much more than just saying, ‘We have to read for fifteen minutes’”) with internal attribution (R3), stimulating the speaker to change their own method and practice (“So I really think you need to focus on implementing <reading programme>”). |

| Category | Code | Participant | % | Facilitator | % | Total | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | n = 1634 | 74% | n = 561 | 26% | n = 2195 | 100% | |

| Degree of collectiveness in dialogue (C) | C1 | 1135 | 51.70% | 278 | 12.67% | 1413 | 64.37% |

| C2 | 493 | 22.46% | 226 | 10.3% | 719 | 32.76% | |

| C3 | 6 | 0.27% | 57 | 2.6% | 63 | 2.87% | |

| Degree of use of multiple data sources (D) | D1 | 1540 | 70.16% | 492 | 22.41% | 2032 | 92.57% |

| D2 | 91 | 4.15% | 62 | 2.82% | 153 | 6.97% | |

| D3 | 3 | 0.14% | 7 | 0.32% | 10 | 0.46% | |

| Depth of reflection (R) | R1 | 1342 | 61.14% | 410 | 18.68% | 1752 | 79.82% |

| R2 | 268 | 12.21% | 134 | 6.10% | 402 | 18.31% | |

| R3 | 24 | 1.1% | 17 | 0.77% | 41 | 1.87% |

| Combi_ID | R | D | C | n= | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C1 | D1 | R1 | 1135 | 51.71% |

| 2 | C2 | D1 | R1 | 551 | 25.10% |

| 3 | C3 | D1 | R1 | 15 | 0.68% |

| 4 | C1 | D2 | R1 | 34 | 1.55% |

| 5 | C2 | D2 | R1 | 15 | 0.68% |

| 6 | C3 | D2 | R1 | 2 | 0.09% |

| 7 | C1 | D3 | R1 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 8 | C2 | D3 | R1 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 9 | C3 | D3 | R1 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 10 | C1 | D1 | R2 | 187 | 8.52% |

| 11 | C2 | D1 | R2 | 115 | 5.24% |

| 12 | C3 | D1 | R2 | 15 | 0.68% |

| 13 | C1 | D2 | R2 | 35 | 1.59% |

| 14 | C2 | D2 | R2 | 30 | 1.37% |

| 15 | C3 | D2 | R2 | 15 | 0.68% |

| 16 | C1 | D3 | R2 | 1 | 0.05% |

| 17 | C2 | D3 | R2 | 3 | 0.14% |

| 18 | C3 | D3 | R2 | 1 | 0.05% |

| 19 | C1 | D1 | R3 | 8 | 0.36% |

| 20 | C2 | D1 | R3 | 2 | 0.09% |

| 21 | C3 | D1 | R3 | 4 | 0.18% |

| 22 | C1 | D2 | R3 | 12 | 0.55% |

| 23 | C2 | D2 | R3 | 3 | 0.14% |

| 24 | C3 | D2 | R3 | 7 | 0.32% |

| 25 | C1 | D3 | R3 | 1 | 0.05% |

| 26 | C2 | D3 | R3 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 27 | C3 | D3 | R3 | 4 | 0.18% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Warmoes, A.; Brown, C.; Decabooter, I.; Consuegra, E. Measuring Reflective Inquiry in Professional Learning Networks: A Conceptual Framework. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030333

Warmoes A, Brown C, Decabooter I, Consuegra E. Measuring Reflective Inquiry in Professional Learning Networks: A Conceptual Framework. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(3):333. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030333

Chicago/Turabian StyleWarmoes, Ariadne, Chris Brown, Iris Decabooter, and Els Consuegra. 2025. "Measuring Reflective Inquiry in Professional Learning Networks: A Conceptual Framework" Education Sciences 15, no. 3: 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030333

APA StyleWarmoes, A., Brown, C., Decabooter, I., & Consuegra, E. (2025). Measuring Reflective Inquiry in Professional Learning Networks: A Conceptual Framework. Education Sciences, 15(3), 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030333