Abstract

Previous studies have demonstrated the significance of leadership training for the professional growth of academics. In the Digital Era, where technological advancements and new learning environments are transforming leadership development, this study seeks to explore whether and how academics’ leadership styles influence their motivation to participate in a leadership training program. Based on survey data from 761 participants directly involved in a leadership development project, this study adopted a path model analysis method and provides novel empirical evidence on whether participants’ leadership styles influence their motivation to participate in leadership training programs. By examining this relationship in the context of the Digital Era, where digital tools and virtual platforms play a significant role, the study sheds light on how leadership approaches drive individuals’ motivation for further development—an aspect that has been underexplored in the past. Focusing on participants from a leadership development project, the study offers practical insights into how different leadership styles may impact engagement and interest in leadership training, particularly in digital and hybrid learning settings. This could help organizations tailor their leadership programs to better address the diverse needs of participants with varying leadership orientations in a digitally connected world.

1. Introduction

The essential role of effective leadership in guiding, motivating and developing high-performance organizations are recognized by plenty of researchers (Zhu & Zayim-Kurtay, 2018; Jacobsen et al., 2022; Cheng & Zhu, 2021, 2023, 2024). Studies have shown that the effectiveness or overall performance of leaders can be improved through leadership trainings (Jacobsen et al., 2022; Day & Sin, 2011; Cheng & Zhu, 2024; Cheng et al., 2023). Participants’ motivation in leadership training plays a central role in the results of the training (Cheng et al., 2024c). It is an important precursor for initiating learning activities (Beier & Kanfer, 2010), and therefore influences trainees’ commitment to training (Brophy, 2010). Accordingly, what affects motivation for joining the leadership training programs can indirectly affect the training outcomes. Studies have investigated the factors that predict participants’ motivation for joining the leadership training programs, for example, leaders facing situational problems related to the psychosocial work environment are more inclined to participate in leadership training, organizational support also enhances their willingness to engage. Similarly, higher levels of organizational commitment and the perception of greater training benefits predict increased motivation to learn (Machin & Treloar, 2004). Furthermore, factors such as the desire to present a well-rounded image to leaders, the ability to network, and an interest in personal development significantly motivate individuals to engage in leadership activities (Stiehl et al., 2015). To this day, there has been no research focusing on the influence of participants leadership styles on their motivation for joining the leadership training programs.

In the evolving landscape of higher education (HE), there is a growing need for leadership styles that promote innovation and growth (Khorshid et al., 2023; Cheng et al., 2024a, 2024b, 2024c). Interest is growing in the study about the impact of leadership styles on the attitudes and behaviors of followers in HE. Transformational leadership has been identified as a key enabler for the higher education sector to cope with an ever-changing environment, both internally and externally (Khorshid et al., 2023), which favorably impacts organizational climate, subordinates, students, and faculty members (Cheng et al., 2024c), and enhances university capacities to fulfill their objectives (Khorshid et al., 2023). Given that leaders and faculty members are integral parts of the organization, their leadership styles can significantly affect their own motivations for engaging in leadership training programs. Specifically, the degree to which training participants exhibit transformational leadership (TFL) and transactional leadership (TAL) behaviors may influence their personal motivations to pursue development opportunities, such as leadership training programs. Understanding this relationship is crucial, as it suggests that leaders’ self-perception of their leadership style could drive their commitment to professional growth and their effectiveness in fostering a positive organizational climate. This underscores the importance of aligning leadership development initiatives with the intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors associated with both TFL and TAL styles (Aarons, 2006). Nevertheless, there is no prior work that tested whether the level of TFL and TAL of the training participants has an impact on their own motivation for joining the leadership training programs. To fill this gap, the current study aims to examine how participants’ leadership styles affect their motivation for joining the leadership training program (MOT).

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Formation

2.1. Theoretical Framework

According to self-determination theory (SDT) (Ryan & Deci, 2017), individuals are more motivated to learn when they experience autonomy, competence, and relatedness—key psychological needs that transformational leaders actively foster. By encouraging independence in decision-making, providing constructive feedback to build confidence, and creating meaningful connections within a team, transformational leaders cultivate an environment that supports intrinsic motivation and lifelong learning. In line with this, transformational leadership theory (Bass, 1999) suggests that individuals with transformational leadership styles inspire personal growth and enhance learning motivation by setting a compelling vision, acting as role models, and intellectually stimulating their team.

On the other hand, goal-setting theory (Locke & Latham, 2002, 2006) emphasizes the role of clearly defined performance expectations in enhancing motivation—an aspect closely aligned with transactional leadership (Avolio & Bass, 2002). Transactional leaders focus on structure, accountability, and contingent rewards, reinforcing specific learning outcomes and encouraging participation through external incentives (Avolio & Bass, 2002). As a result, individuals with transactional leadership styles may be driven more by extrinsic motivation, engaging in training to meet performance benchmarks, earn rewards, or gain career advantages.

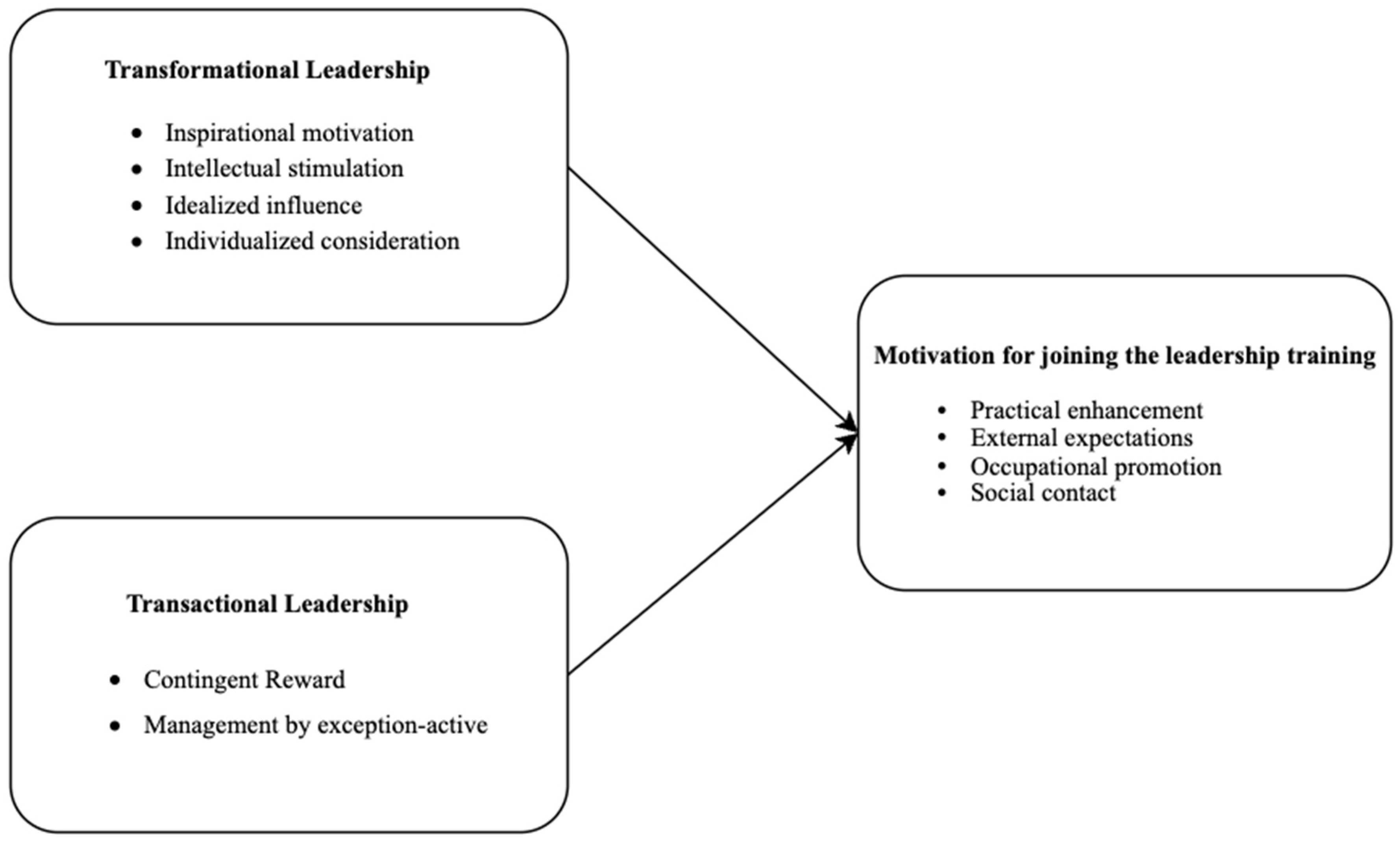

By integrating these theoretical perspectives, it becomes evident that both transformational and transactional leadership styles influence individuals’ motivation to participate in leadership training, albeit through different mechanisms (Figure 1). While transformational leaders nurture a passion for learning by fostering intrinsic motivation, transactional leaders provide structure and extrinsic incentives that encourage goal-directed behavior. Recognizing the complementary nature of these approaches can help organizations design more effective leadership development programs that cater to diverse motivational needs.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model (Ryan & Deci, 2017; Bass, 1999; Locke & Latham, 2002, 2006; Avolio & Bass, 2002).

2.2. Motivation for Joining Leadership Training

A number of studies have highlighted the role of motivation in learning outcomes (Douglas et al., 2020; Ryan & Deci, 2017). The motivation to participate in training is a key driver in initiating learning activities (Cheng et al., 2024c), as a result, it has an impact on trainees’ commitment to the training (Brophy, 2010). As academic members, their motivation for taking part in leadership training courses vary from advancing their knowledge and skills to social interaction (Loizzo et al., 2017; Kao et al., 2011). During the last decade, the literature has focused on understanding their motivation for learning and its relationship to learning outcomes results (Douglas et al., 2020; Cheng et al., 2024c). However, despite the established benefits of training motivation, no prior work has examined whether the leadership styles of the training participants have an impact on their own motivation for joining the leadership training program, indicating a need for further research into leadership styles’ impact on motivation for joining leadership training programs.

2.3. Transformational Leadership and Motivation for Joining Leadership Training

Transformational leadership (TFL) is defined as a leadership style that motivates employees to change their beliefs, values, and abilities, ultimately enhancing their performance and aligning individual goals with organizational objectives (Avolio & Bass, 2002; Chen & Cuervo, 2022). This leadership style encourages innovation by stimulating followers to develop new methods for task completion and providing them with the autonomy to pursue these innovations, which is crucial in dynamic work environments (Chua & Ayoko, 2021). Empirical studies indicate a significant positive relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement, suggesting that employees’ perceptions of transformational leadership can enhance their commitment to work (Chua & Ayoko, 2021; Wang et al., 2011). Research highlights that transformational leaders play a crucial role in fostering an innovative work climate by providing personalized attention and support to their followers, which in turn enhances motivation and engagement (Chua & Ayoko, 2021). The relationship between transformational leadership and learning organizations is well-documented, with TFL positively impacting organizational learning capabilities and performance, thereby fostering a culture of continuous improvement (Chua & Ayoko, 2021). Despite the established benefits of transformational leadership, no prior work has examined whether the level of transformational leadership of the training participants has an impact on their own motivation for joining the leadership training program, indicating a need for further research into its impact on motivation for joining the leadership training program. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is put forth:

Hypothesis 1.

Participants’ transformational leadership styles positively influence their motivation to participate in leadership training.

2.4. Transactional Leadership Style and Motivation for Joining Leadership Training

Transactional leadership is characterized by an exchange process between leaders and followers, where rewards are provided for achieving specific goals, thus creating a clear understanding of expectations and outcomes (Lan et al., 2019; Samodien et al., 2024). The primary components of transactional leadership include contingent rewards and management by exception active. Contingent rewards involve providing incentives for meeting performance standards, while management by exception active focuses on addressing deviations from established norms (Avolio & Bass, 2002; Samodien et al., 2024). Research indicates that transactional leadership can effectively reduce workplace anxiety by clarifying roles and expectations, allowing employees to focus on organizational goals such as quality improvement and cost reduction (Khan, 2017; Lan et al., 2019). However, while transactional leadership can motivate employees through rewards, it may also lead to a lack of intrinsic motivation. Employees might prioritize rewards over personal growth or job satisfaction, potentially compromising overall performance quality (Khan, 2017; Lee & Ding, 2020). Despite its limitations, transactional leadership remains a prevalent style in various organizational contexts, particularly in educational settings, where clear performance metrics and rewards are essential for student and staff motivation (Samodien et al., 2024; Lee & Ding, 2020). Overall, while transactional leadership can provide structure and motivation through clear rewards, it is essential to balance this approach with opportunities for intrinsic motivation and personal development to foster a more engaged and high-performing workforce (Khan, 2017; Lee & Ding, 2020). Yet, no prior work has examined whether the level of transactional leadership of the training participants has an impact on their own motivation for joining the leadership training program. This gap indicates a need to measure the contribution of the TAL level of the training participants on their own motivation for joining the leadership training program. Thus, the following hypothesis is put forth:

Hypothesis 2.

Participants’ transactional leadership styles influence their motivation to participate in leadership training.

2.5. Research Questions

Based on the above research gaps, two research questions are put forth:

- How does transformational leadership (TFL) of the training participants affect their own motivation for joining the leadership training program?

- How does transactional leadership (TAL) of the training participants affect their own motivation for joining the leadership training program?

3. Methods

3.1. Context of the Study

This study was carried out as part of a capacity-building project. The aim of the leadership training program was to develop the leadership skills of academic staff, with a focus on developing the educational leadership of university educational leaders and faculty members. This study provides the quantitative results of blended leadership training programs (including online live sessions, self-study on digital learning platforms, and offline sessions) undertaken during the period of 2020–2022.

3.2. Participants

The number of participants directly involved in leadership development was 761, including lecturers, researchers, assistant professors, professors, deans, etc. The participants’ demographic profile (N = 761) was analyzed after removing the incomplete and unengaged responses. The professional leadership experience of academic members (Appendix A) ranged from 1 to 5 years (45.1%), 6–10 years (14.7%), and over 10 years (9.2%); 57.7% of the respondents were male and 42.3% were female. Most participants were aged 21–30 (44.7%), followed by 31–40 (34.4%) and over 41 (20.9%).

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Motivation for Joining Leadership Training

Drawing from Kao et al. (2011), the construct of motivation to participate in the leadership training program (MOT) was taken, which was validated in Cheng et al. (2024c)’s research. This multidimensional 12-item construct comprises four dimensions: occupational promotion, practical enhancement, social contact, and external expectations (Kao et al., 2011).

3.3.2. Transformational and Transactional Leadership Style

The transformational leadership style and transactional leadership style were measured through the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) (Avolio & Bass, 2004). This 18-item multidimensional construct comprises four dimensions of TFL (including idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration) and two dimensions of TAL (contingent reward and MBEA, management by exception active), validated by Cheng et al. (2024c) and Løvaas et al. (2020).

To measure the latent concepts, namely MOT, TFL, and TAL, participants responded using a five-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated strongly disagree and 5 indicated strongly agree.

3.4. Data Collection

Following the formulation of the initial questionnaire, two research experts were involved in examining and commenting on all the items. A pilot study was then carried out with a select group of respondents to test the reliability of the adapted measurements. Reliability and validity analysis of the pilot study served as the basis for the final 30-item survey, covering general respondent characteristics and key constructs mentioned in Section 3.3. We collected the data after each edition of the training.

3.5. Data Analysis

For data sorting and descriptive analysis, SPSS 28 was used. Next, we used Mplus 8.3 for path model analysis. Two steps of model fit assessment were carried out for Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and structural model (Muthén et al., 2017). First, the composite reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity assessment was performed using Mplus. Moreover, as a measure of verification, chi-square, comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized squared residual (SRMR), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) (Mueller & Hancock, 2019) were used. Thereafter, these model fit indices were also used to test the structural model.

4. Findings

4.1. Measurement Validation

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was employed in this study to evaluate the adequacy of the measurement model (Table 1). Relative chi-square (χ2/df) ≤ 5 indicates an acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is a mediocre fit between 0.08 and 0.10 and a good fit below 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). CFI and TLI > 0.9 (Byrne, 1994), TLI close to 0.9 is regarded as suffering but not a bad model (Portela, 2012), (standardized) root mean square residual (SRMR) < 0.08 (Byrne, 1994). It is thereby concluded that the overall fit of this CFA is accepted. The constructs and sub-constructs and the respective number of measured items and their Cronbach’s alpha and factor loadings are illustrated in Appendix B. Items with factor loadings above 0.4 were considered acceptable (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Cronbach’s alpha > 0.70 met the threshold recommended by Hair et al. (2016), Cronbach’s alpha > 0.60 was met as recommended by Joseph and Arthor (2007). The average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) (Table 2) were used to evaluate the measurement model’s fitness. AVE ought to be greater than 0.5. Nevertheless, the value of 0.4 is deemed acceptable because if the AVE value < 0.5, but the composite reliability > 0.6, the construct’s convergent validity is acceptable (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Each construct is shown to be convergence valid.

Table 1.

Fit indices for measurement models.

Table 2.

CR, multicollinearity, convergence validity, and discriminant validity of measurement model (N = 761).

4.2. Structural Model Evaluation

Table 3 shows that all structural model fit indices are within the acceptable range (Dash & Paul, 2021; Mueller & Hancock, 2019), which was evaluated with the standard indices: chi-square, CFI, SRMR, RMSEA, and TLI.

Table 3.

Structural equation model fit indices.

Table 4 shows the beta (β) values, or path coefficients, and the t-statistic. The results indicate that not all the dimensions of transformational leadership and transactional leadership are related to participants’ motivation for joining the leadership training program. Robust positive relationships are found between IM and PE (β = 0.534, p < 0.001, t = 3.253), IS and PE (β = −0.382, p < 0.05, t = −2.103), II and SC (β = 0.231, p < 0.05, t = 2.066), and IM and SC (β = 0.313, p < 0.05, t = 2.030), which supported three dimensions of transformational leadership related to participants’ motivation for joining the leadership training program.

Table 4.

Path coefficients.

Robust positive relationships are also found between MBEA and OP (β = 0.130, p < 0.05, t = 2.457), MBEA and EE (β = 0.221, p < 0.001, t = 4.495), and MBEA and SC (β = 0.149, p < 0.01, t = 2.991), which supports that only MBEA, management by exception active, in transactional leadership is related to participants’ motivation for joining the leadership training program.

A substantial amount of variance accounted for the entire sample and dimensions is indicated by R-square values (Cohen, 1988). In particular, R-square for PE was 0.29, suggesting that 29% of the variance in PE can be explained by the predictor variables IM and IS. R-square for OP was 0.22, showing that MBEA accounts for 22% of OP’s variance. EE had an R-square of 0.09, suggesting that MBEA explains 9% of EE’s variance. Lastly, SC had an R-square of 0.23, indicating that II, IM, and MBEA collectively account for 23% of SC’s variance.

5. Discussion

This study is conducted to understand how the leadership styles influence participants’ motivation for joining leadership training programs. The results about how participants’ transformational leadership and transactional leadership influence their motivations for joining leadership training programs are discussed below.

5.1. How Does Transformational Leadership (TFL) of the Training Participants Affect Their Own Motivation for Joining the Leadership Training Program? (RQ1)

Transformational leadership theory suggests that leaders support personal growth and enhance motivation and engagement in professional development. The findings indicate that specific facets of transformational leadership significantly influence participants’ motivations for joining leadership training programs. Our study extends this theory by demonstrating that specific dimensions of transformational leadership are significantly related to the motivation to participate in leadership training. Notably, inspirational motivation demonstrated a robust positive relationship with practical enhancement, suggesting that leaders who articulate a compelling vision and inspire confidence effectively motivate individuals, including themselves, seeking to enhance their practical skills. This aligns with previous research highlighting the role of inspirational motivation in boosting employee engagement and performance (Avolio & Bass, 2004; Løvaas et al., 2020). Conversely, intellectual stimulation exhibited a negative relationship with PE, indicating that leaders who challenge existing assumptions and encourage innovative thinking may inadvertently deter individuals primarily focused on practical skill development. This finding contrasts with studies that emphasize the positive aspects of intellectual stimulation in fostering creativity and adaptability (Afsar & Umrani, 2020). Additionally, idealized influence and inspirational motivation both showed positive associations with social contact, implying that leaders who serve as role models and inspire others have strong desires for social interaction within training contexts. These results underscore the multifaceted impact of transformational leadership components on individuals’ motivations, suggesting that while inspirational and charismatic leadership can drive engagement in training programs, an overemphasis on intellectual challenges might have unintended effects on those seeking practical skill enhancement.

Furthermore, the results also implicate that the leadership training programs should be tailored to emphasize inspirational motivation to boost participants’ motivation for practical enhancement. Institutions and training programs should focus on delivering clear visions, inspiring messages, and confidence-building strategies to meet participants’ skill development needs. In addition, leadership training programs should create spaces for networking, mentorship opportunities, and team-building activities to enhance social bonds. Regular feedback loops should be implemented to ensure that participants’ needs are being met, especially in balancing intellectual challenges with practical takeaways.

The results highlight the differential effects of transformational leadership dimensions on motivation, shedding light on both positive influences and potential unintended consequences of certain leadership behaviors. Additionally, this study contributes to the existing body of leadership and motivation research by integrating SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2017) and transformational leadership theory (Bass, 1999) to examine how different dimensions of participants transformational leadership styles influence participants’ motivation to engage in leadership training programs. By empirically validating these relationships, these findings enhance the theoretical understanding of how leadership styles shape learning motivation in professional development contexts.

5.2. How Does Transactional Leadership (TAL) of the Training Participants Affect Their Own Motivation for Joining the Leadership Training Program? (RQ2)

The results indicate that management by exception active (MBEA), a component of transactional leadership, significantly influences participants’ motivations for enrolling in leadership training programs. Specifically, MBEA shows positive relationships with occupational promotion, external expectations, and social contact. This suggests that leaders who actively monitor performance and intervene to correct deviations can motivate individuals driven by career advancement, external obligations, and social interaction. These findings align with previous research highlighting that transactional leadership, through its emphasis on structured environments and contingent rewards, effectively motivates individuals seeking clear expectations and extrinsic rewards (Lan et al., 2019; Samodien et al., 2024). However, it is important to note that while transactional leadership can enhance motivation in specific contexts, it may not foster intrinsic motivation or creativity to the same extent as transformational leadership (Afsar & Umrani, 2020; Wang et al., 2011; Khan, 2017; Lee & Ding, 2020). Therefore, leadership training programs should consider integrating both transactional and transformational elements to address diverse participant motivations effectively.

In addition, the results contribute to the leadership and motivation literature and enhance theoretical understanding by integrating goal-setting theory (Locke & Latham, 2002, 2006) and transactional leadership theory (Avolio & Bass, 2002) to examine how participants’ transactional leadership styles influence their motivation to participate in leadership training programs. The findings emphasize the specific role of management by exception active in driving training motivation, refining existing leadership theories, and offering practical insights for leadership development initiatives. Goal-setting theory posits that clearly defined performance expectations enhance motivation, particularly when individuals receive structured feedback and rewards. The findings support this theory by demonstrating that MBEA is positively associated with various motivational dimensions. Specifically, the positive relationships between MBEA and occupational promotion highlight how structured expectations and corrective feedback enhance participants’ motivation to engage in leadership training.

6. Limitation and Recommendations for Further Research

A few limitations in this study need to be noted. Firstly, there might be other potential variables influencing the relationships studied; future research could look into this issue. Secondly, this study is the reliance on self-reported survey data. Self-reported responses are subject to biases such as social desirability bias, where participants may provide answers that they believe are more socially acceptable rather than their true feelings or behaviors. This factor could potentially affect the reliability and validity of the data, and future studies may benefit from incorporating objective measures or triangulating self-reported data with other data collection methods to enhance robustness. Thirdly, complementing the quantitative method, a qualitative approach can offer in-depth insights into the complex dynamics between leadership styles and motivation across various dimensions, as researchers can gain a more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation by a mixed-methods approach.

7. Conclusions and Implication

In this study, we obtained results that highlight the distinct roles that transformational and transactional leadership styles play in motivating participants to participate in leadership training programs. Transformational leadership, particularly through inspirational motivation and idealized influence, positively correlates with motivations for practical enhancement and social contact. In the realm of transactional leadership, management by exception active shows positive associations with motivations for occupational promotion, external expectations, and social contact, implying that active performance monitoring and corrective actions appeal to participants driven by career advancement, external obligations, and social engagement.

Our study makes a contribution to the transformational transactional leadership literature by proposing and empirically testing a novel model in which the level of transformational leadership (TFL) and transactional leadership (TAL) of the training participants influence their own motivation for joining the leadership training programs. Our study also provides practical implications for leadership development programs, which should be tailored to emphasize inspirational motivation to boost participants’ motivation for practical enhancement. Institutions and training programs should focus on delivering clear visions, inspiring messages, and confidence-building strategies to meet participants’ skill development needs. Furthermore, leadership training programs should create spaces for networking, mentorship opportunities, and team-building activities to enhance social bonds. Additionally, leadership training programs should consider integrating both transactional and transformational elements, tailoring approaches to address the diverse motivations of participants effectively, and enhancing the effectiveness of the leadership training program.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.C.; methodology, Z.C.; formal analysis, Z.C.; resources, Z.C. and C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.C.; writing—review and editing, C.Z.; visualization, Z.C.; supervision, C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest related to the authorship and publication of this article.

Appendix A. The Demographic Characteristics of the Participants (N = 761)

| Variables | f (Participants) | % (Percentage) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 439 | 57.7 |

| Female | 322 | 42.3 |

| Age | ||

| 21–30 | 340 | 44.7 |

| 31–40 | 262 | 34.4 |

| Above 41 | 159 | 20.9 |

| Work-related leadership experience | ||

| 1–5 years | 343 | 45.1 |

| 6–10 years | 112 | 14.7 |

| Over 10 years | 70 | 9.2 |

Appendix B. The Constructs, Sub-Constructs, and the Factor Loadings

| Constructs | Sub-Constructs and Items | Loading |

| Motivation | Practical enhancement (M = 4.28, SD = 0.67, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73) | Loading |

| I participate in leadership development through MOOC to adapt to new leadership styles in the future | 0.668 | |

| I participate in leadership training to achieve accountability in leadership at my institution I participate in leadership training to increase competence in leadership | 0.717 | |

| I participate in leadership training to do something more for leadership in my institution | 0.684 | |

| Occupational promotion (M = 4.14, SD = 0.68, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.68) | Loading | |

| I participate in leadership training for getting better qualifications in leadership | 0.728 | |

| I participate in leadership training for preparing for my career/job | 0.687 | |

| I participate in leadership training for getting a better job | 0.545 | |

| External expectations (M = 3.16, SD = 0.11, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83) | Loading | |

| I participate in leadership development through MOOC due to others’ participation | 0.814 | |

| I participate in leadership development through MOOC due to someone telling me about its advantages | 0.886 | |

| I participate in leadership development through MOOC to meet institutional requirements | 0.698 | |

| Social contact (M = 3.95, SD = 0.79, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79) | Loading | |

| I participate in leadership training to make more friends with the same interest | 0.789 | |

| I participate in leadership training to exchange my social relationships | 0.824 | |

| I participate in leadership training to exchange ideas about leadership | 0.639 | |

| Transformational Leadership | Idealized influence (M = 4.14, SD = 0.54, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81) | Loading |

| After the training, I would go beyond self-interest for the good of the group | 0.714 | |

| After the training, I can specify the importance of having a strong sense of purpose | 0.846 | |

| After the training, I would consider more of the moral and ethical consequences of decisions | 0.766 | |

| Inspirational motivation (M = 4.23, SD = 0.55, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83) | Loading | |

| After the training, I would talk optimistically about the future | 0.720 | |

| After the training, I can develop a team attitude and spirit among members of staff | 0.789 | |

| After the training, I can express more confidence that goals will be achieved | 0.853 | |

| Intellectual stimulation (M = 4.19, SD = 0.53, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83) | Loading | |

| After the training, I would re-examine critical assumptions to question whether they are appropriate | 0.785 | |

| After the training, I can suggest new ways of looking at how to complete assignments | 0.798 | |

| After the training, I seek different perspectives when solving problems | 0.772 | |

| Individualized consideration (M = 4.12, SD = 0.59, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76) | Loading | |

| After the training, I’ll spend time teaching and coaching | 0.669 | |

| After the training, I’ll treat followers/others as individuals rather than just as a member of a group | 0.753 | |

| After the training, I’ll consider an individual as having different needs, abilities, and aspirations from others | 0.732 | |

| Transactional leadership | Contingent Reward (M = 4.19, SD = 0.55, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80) | Loading |

| I provide others with assistance in exchange for their efforts | 0.805 | |

| I discuss in specific terms who is responsible for achieving performance targets | 0.802 | |

| I express satisfaction when others meet expectations | 0.697 | |

| MBEA, management by exception active (M = 3.79, SD = 0.85, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89) | Loading | |

| I concentrate my full attention on dealing with mistakes, complaints, and failures | 0.843 | |

| I keep track of all mistakes | 0.874 | |

| I direct my attention toward failures to meet standards | 0.775 |

References

- Aarons, G. A. (2006). Transformational and transactional leadership: Association with attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services, 57(8), 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Afsar, B., & Umrani, W. A. (2020). Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior: The role of motivation to learn, task complexity and innovation climate. European Journal of Innovation Management, 23(3), 402–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B. J., & Bass, B. M. (2002). Developing potential across a full range of leadership TM: Cases on transactional and transformational leadership. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B. J., & Bass, B. M. (2004). Multifactor leadership questionnaire. Mind Garden. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. M. (1999). Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(1), 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, M. E., & Kanfer, R. (2010). Motivation in training and development: A phase perspective. In S. W. J. Kozlowski, & E. Salas (Eds.), Learning, training, and development in organizations (pp. 65–97). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy, J. E. (2010). Motivating students to learn (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. (1994). Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S., & Cuervo, J. C. (2022). The influence of transformational leadership on work engagement in the context of learning organization mediated by employees’ motivation. Learning Organization, 29(5), 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., Caliskan, A., & Zhu, C. (2023). Academics’ motivation for joining an educational leadership training programme and their perceived effectiveness: Insights from an EU- China cooperative project. European Journal of Education, 59(1), e12576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., Dinh, N. B. K., Caliskan, A., & Zhu, C. (2024a). Dimensions of digital academic leadership in higher education: A systematic review. In ALTA’23 advanced learning technologies and applications conference proceedings: ALTA’23—“Advanced learning technologies and applications. Empowering learning through digital pedagogy” (pp. 63–68). Kaunas University of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z., Khuyen, D. N. B., Caliskan, A., & Zhu, C. (2024b). A systematic review of digital academic leadership in higher education. International Journal of Higher Education, 13(4), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., & Zhu, C. (2021). Academic members’ perceptions of educational leadership and perceived need for leadership capacity building in Chinese higher education institutions academic members’ perceptions of educational leadership. Chinese Education & Society, 54(5–6), 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., & Zhu, C. (2023). Leadership styles of mid-level educational leaders perceived by academic members: An exploratory study among Chinese universities. Research in Educational Administration & Leadership, 8(4), 762–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., & Zhu, C. (2024). Educational leadership styles and practices perceived by academics: An exploratory study of selected Chinese universities. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., Zhu, C., & Dinh, N. B. K. (2024c). Perceived changes in transformational leadership: The role of motivation and perceived skills in educational leadership training under an EU-China cooperation project. European Journal of Education, 59(3), e12636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J., & Ayoko, O. B. (2021). Employees’ self-determined motivation, transformational leadership and work engagement. Journal of Management and Organization, 27(3), 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, G., & Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs. PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D. V., & Sin, H.-P. (2011). Longitudinal tests of an integrative model of leader development: Charting and understanding developmental trajectories. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K., Merzdorf, H. E., Hicks, N., Sarfaz, M. I., & Bermel, P. (2020). Challenges to assessing motivation in MOOC learners: An application of an argument-based approach. Computer & Education, 150, 103829. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, C. B., Andersen, L. B., Bøllingtoft, A., & Eriksen, T. L. M. (2022). Can leadership training improve organizational effectiveness? Evidence from a randomized field experiment on transformational and transactional leadership. Public Administration Review, 82(1), 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, F. H., & Arthor, H. M. (2007). Research method for business. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, C. P., Wu, Y., & Tsai, C. (2011). Elementary school teachers’ motivation toward web-based professional development, and the relationship with Internet self-efficacy and belief about web-based learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(2011), 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N. (2017). Adaptive or transactional leadership in current higher education: A brief comparison. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(3), 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshid, S., Mehdiabadi, A., Spulbar, C., Birau, R., & Mitroi, A. T. (2023). Modelling the effect of transformational leadership on entrepreneurial orientation in academic department: The mediating role of faculty members’ speaking up. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 36, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T. S., Chang, I. H., Ma, T. C., Zhang, L. P., & Chuang, K. C. (2019). Influences of transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and patriarchal leadership on job satisfaction of cram school faculty members. Sustainability, 11(12), 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. C. C., & Ding, A. Y. L. (2020). Comparing empowering, transformational, and transactional leadership on supervisory coaching and job performance: A multilevel perspective. PsyCh Journal, 9(5), 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2006). New directions in goal-setting theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizzo, J., Ertmer, P., Watson, W., Watson, & Lee, S. (2017). Adults as self-directed and determined to set and achieve personal learning goals in MOOCs: Learners’ perceptions of MOOC motivation, success, and completion. Online Learning, 21(2), 10-24059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løvaas, B. J., Jungert, T., Van den Broeck, A., & Haug, H. (2020). Does managers’ motivation matter? Exploring the associations between motivation, transformational leadership, and innovation in a religious organization. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 30(4), 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machin, M. A., & Treloar, C. A. (2004). Predictors of motivation to learn when training is mandatory. In M. Katsikitis (Ed.), Proceedings of the 39th Australian psychological society annual conference, 29 September–3 October, Sydney, Australia (pp. 157–161). Commonwealth Carelink Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, R. O., & Hancock, G. R. (2019). Structural equation modelling. In G. R. Hancock, L. M. Stapleton, & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences (pp. 445–456). Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, B. O., Muthén, L. K., & Asparouhov, T. (2017). Regression and mediation analysis using mplus. Muthén and Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Portela, D. M. P. (2012). Contributo das Técnicas de Análise Fatorial para o Estudo do Programa “Ocupação Científica de Jovens nas Férias” [Master’s Thesis, Universidade Aberta]. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Samodien, M., Du Plessis, M., & Van Vuuren, C. J. (2024). Enhancing higher education performance: Transformational, transactional and agile leadership. SA Journal of Human Resource Management/SA Tydskrif vir Menslikehulpbronbestuur, 22(0), a2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiehl, S. K., Felfe, J., Elprana, G., & Gatzka, M. B. (2015). The role of motivation to lead for leadership training effectiveness. International Journal of Training and Development, 19(2), 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., Oh, I. S., Courtright, S. H., & Colbert, A. E. (2011). Transformational leadership and performance across criteria and levels: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of research. Group and Organization Management, 36, 223–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C., & Zayim-Kurtay, M. (2018). University governance and academic leadership: Perceptions of European and Chinese university staff and perceived need for capacity building. European Journal of Higher Education, 8(4), 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).