Statistical Tables in Spanish Primary School Textbooks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Types of Tables and Their Semiotic Complexity

2.1.1. Interpreting Statistical Tables

- External identification, to find the conceptual and real-world referents which support the information contained in the table (e.g., variables being represented).

- Internal identification of the relevant dimensions of variation in the table content (e.g., values range or intervals of variation for each variable represented).

- Perception of the correspondence, by which the reader uses the graphical dimensions levels in the table to draw conclusions about the levels of each conceptual dimension in the real world.

2.1.2. Classification of Statistical Tables and Their Semiotic Complexity

- Data table. They are used to register the values of one or several variables for each element of the population or sample, particularly when these values are collected. Although the idea of a variable and its values are implicitly used, the concepts of frequency or frequency distribution are not needed to work with these tables. Pallauta and Arteaga [29] assigned a complexity level C2 to the data tables. The level C1 corresponds to the representation of isolated data [28]: for example, data from only one student. An example is given in Figure 1.

- One-variable distribution table. These tables display the frequency distribution of a statistical variable, which may be categorical or quantitative. In these tables, the concepts of variable, frequency, and frequency distribution are implicit, and Pallauta and Arteaga [29] assigned to them a complexity level C3. Furthermore, in our work, we subdivide these types of tables into three types, which are described in Section 4.1.

- Two-way tables. They represent the joint distribution of a two-dimensional statistical variable and can be classified at complexity level C4 [29]. New implicit mathematical objects appear, such as conditional, compound, and marginal frequencies or statistical association between the variables.

2.2. The Role of Context in Mathematics and Statistics

2.3. Previous Research

3. Methods

3.1. Sample of Textbooks and Activities

3.2. Analysis

3.3. Categories for the Different Variables

3.3.1. Type of Tables and Data Represented

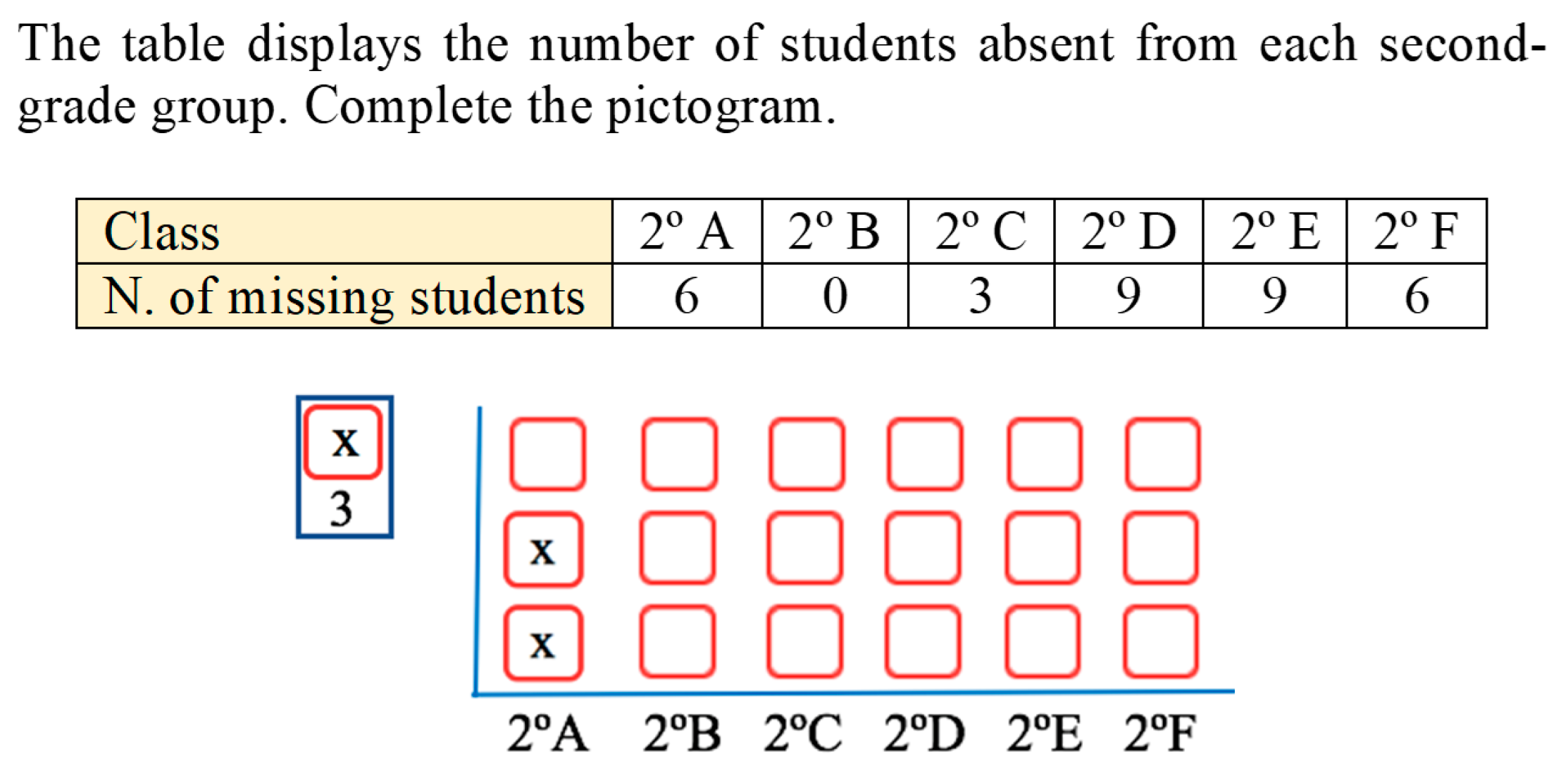

- Counting tables. In some frequency tables, a column is added to facilitate the calculation of the absolute frequency, where generally, dashes or other marks are used to represent each value of the variable collected. In the early grades, this column facilitates the data organisation, since children still have immature thinking to perform this process by themselves [49]. They are characterised in that each occurrence of a certain modality or value of the variable is recorded using a symbol in an additional column and the specific variable category (row) (see example in Figure 2).

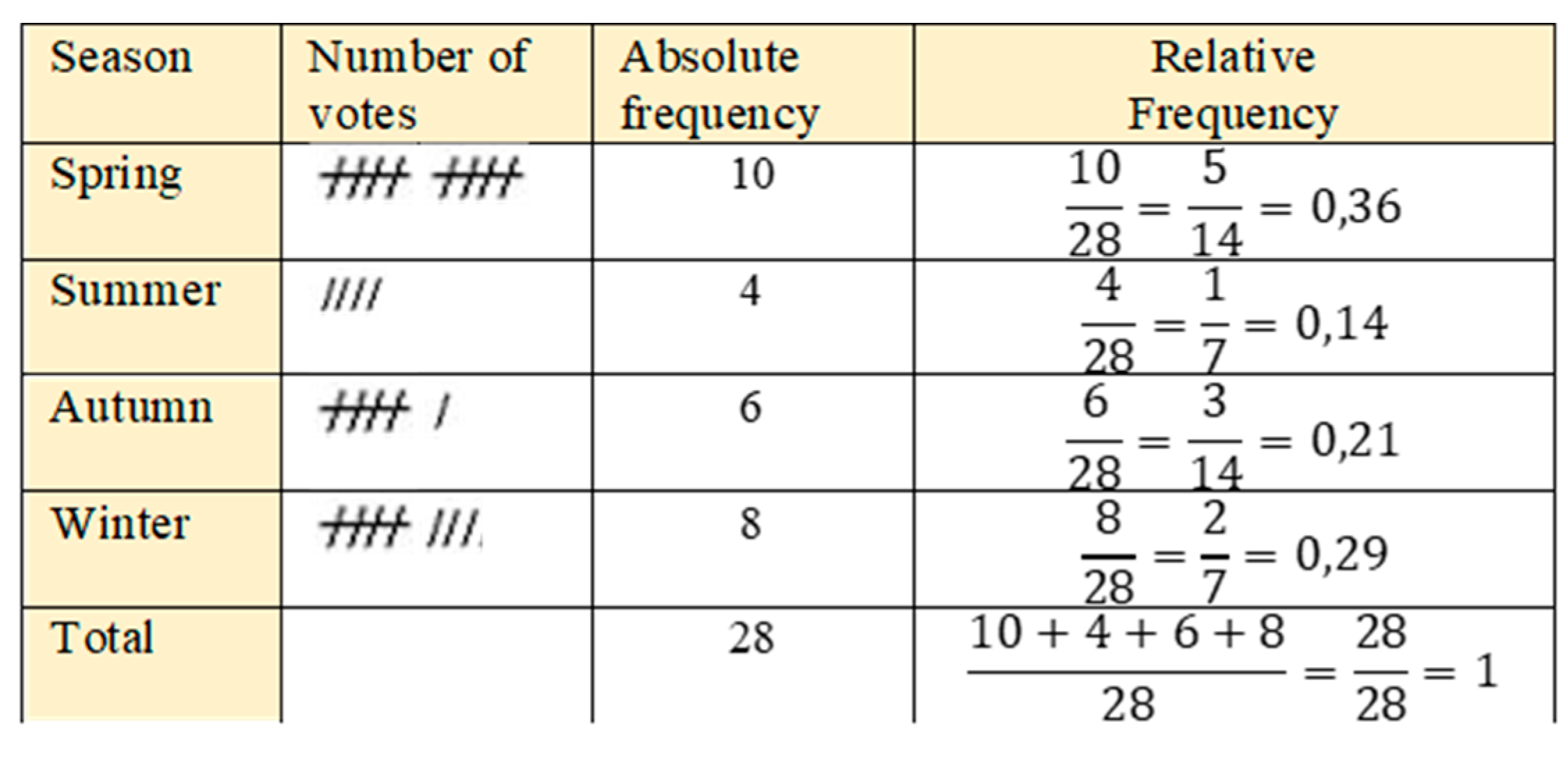

- Frequency tables. In addition to or instead of the counting column, frequency tables usually have different columns in which the absolute frequency, relative frequency, or percentage of the variable distribution are represented. Figure 3 shows an example from a 6th grade textbook, which includes the counting column and the absolute and relative frequency for a qualitative variable. In the relative frequency column, we find the expression of relative frequencies in fractions and decimal numbers. In the last row, the totals and their calculation are explained.

- Frequency tables of data grouped in intervals. In this type of table, the values of a numerical variable are grouped into class intervals, which implies dealing with intervals, and their extremes, as well as using approximate values in the calculation of summary statistics. Figure 4 shows an example used to explain the construction of the histogram and frequency polygon directed at grade 6.

- Two-way table. These tables present the cross classification of two statistical variables and involve a C4 level of semiotic complexity [28]. Three types of frequencies can be calculated in these tables: joint (compound), marginal to the row or column, and conditional to the row or column. Therefore, three types of distributions such as joint, marginal, or conditional are also implicit.

3.3.2. Activities Proposed to the Students

3.3.3. Data Contexts

- Personal context. Problems classified in this group focus on the child or his/her family, as well as the peer group’s frequent activities. Examples include (but are not limited to) those involving the age or physical characteristics of students, personal preferences, sports, school tasks, or games. For example, the tables displayed in Figure 1, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 or Figure 10 were classified in personal contexts.

- Occupational context. In this category, the context is focused on the world of work. Examples are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 9. We also found activities linked to production on a livestock farm, sales in a store, number of animals on a farm, number of excursions organized by a travel agency, and rooms booked in a hotel.

- Societal context. Problems framed in situations developed in the local community, or a wider society, to which the learner has access through different media, or social networks. One example is presented in Figure 3; others include types of vehicles observed by the student, types of vehicles in a parking lot, visitors to a museum, the number of people practicing different sports in a ski resort, the preferred schedules of children and adults in a swimming pool, destinations of airline passengers, movie viewers of different film directors, electricity consumption, and abandoned pets picked up in an animal centre.

- Scientific context. This context is linked to different applications of mathematics to the natural world, science, and technology. Common context, both in 5th and 6th grades in both editorials was meteorology. Another example used in 6th grade in Anaya was related to endangered species.

4. Results

4.1. Type of Tables and Data Represented

4.2. Activities Proposed to the Students

4.3. Data Contexts

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| SM1 | Bernabeu, J., Garín, M., & Modrego, R. (2019). Matemáticas 1 primaria. Más Savia. SM. |

| SM2 | Bernabeu, J., Garín, M., Martín G., Herrero, N., Morales, F., Vidal J.M., & Pérez M.N. (2019). Matemáticas 2 primaria. Más Savia. SM. |

| SM3 | Bernabeu, J., Garín, M., de Casacuberta, A., Cusó, M., Pérez M.N., Morales, F., Vidal, J.M., & Valvanera, A. (2019). Matemáticas 3 primaria. Más Savia. SM. |

| SM4 | Bernabeu, J., Garín, M., Díaz, J.G., García, M., Pérez M.N., Morales, F., Vidal, J.M., & Bellido, A. (2019). Matemáticas 4 primaria. Más Savia. SM. |

| SM5 | Garín, M., Bernabeu, J., Bellido, A., Pérez, M.N., Morales, F., Vidal, J.M, Armas, Z., González, Y., Macías, C., Peña, M., & Navarro, A. (2019). Matemáticas 5 primaria. Más Savia. SM. |

| SM6 | Bernabeu, J., González, Y., Garín, M., Nieco M., Pérez, B., García, M., Pérez, M.N., Morales, F., Vidal, J.M., & Bellido, A. (2019). Matemáticas 6 primaria. Más Savia. SM. |

| A1 | Carvajal, A. I., & de la Rosa, L. I. (2019). Matemáticas 1. Pieza a Pieza. Anaya. |

| A2 | Carvajal, A. I., & de la Rosa, L. I. (2018). Matemáticas 2. Pieza a Pieza. Anaya. |

| A3 | Ferrero, L., Gómez, J. M., Martín, P., & Quevedo, V. J. (2019). Matemáticas 3. Pieza a Pieza. Anaya. |

| A4 | Carvajal, A. I., Ferrero, L., Gómez, J. M., Martín, P., & de la Rosa, L. I. (2018). Matemáticas 4. Pieza a Pieza. Anaya. |

| A5 | Ferrero, L., Gómez, J. M., Martín, P., & Quevedo, V. J. (2018). Matemáticas 5. Pieza a Pieza. Anaya. |

| A6 | Carvajal, A. I., Ferrero, L., Gómez, J. M., Martín, P., & de la Rosa, L. I. (2019). Matemáticas 6. Pieza a Pieza. Anaya. |

References

- Estrella, S. El formato tabular: Una revisión de literatura. Actual. Investig. Educ. 2014, 14, 449–478. [Google Scholar]

- Estrella, S.; Mena-Lorca, A.; Olfos-Ayarza, R. Naturaleza del objeto matemático Tabla. MAGIS 2017, 10, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Postigo, Y.; Pozo, J.I. Cuando una gráfica vale más que 1000 datos: La interpretación de gráficas por alumnos adolescentes. Infancia Aprendizaje 2000, 90, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gal, I. Adults’ statistical literacy: Meanings, components, responsibilities. Int. Stat. Rev. 2002, 70, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, I. Understanding statistical literacy: About knowledge of contexts and models. In Actas del Tercer Congreso Internacional Virtual de Educación Estadística; Contreras, J.M., Gea, M.M., López-Martín, M.M., Molina-Portillo, E., Eds.; University of Granada: Granada, Spain, 2019; Available online: www.ugr.es/local/fqm126/civeest.htm (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- Johannssen, A.; Chukhrova, N.; Schmal, F.; Stabenow, K. Statistical literacy—Misuse of statistics and its consequences. J. Stat. Data Sci. Educ. 2021, 29, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Definitions and models of statistical literacy: A literature review. Open Rev. Educ. Res. 2017, 4, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Engel, J. Statistical literacy for active citizenship: A call for data science education. Stat. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 16, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (MECD). Real Decreto 126/2014, de 28 de Febrero, Por el Que Se Establece el Currículo Básico de la Educación Primaria; MECD: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional (MEFP). Real Decreto 157/2022, de 1 de Marzo, Por el Que Se Establecen la Ordenación y las Enseñanzas Mínimas de la Educación Primaria; MEFP: Madrid, Spain, 2022.

- Koschat, M.A. A case for simple tables. Am. Stat. 2005, 59, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabucio, F.; Martí, E.; Enfedaque, J.; Gilabert, S.; Konstantinidou, A. Niveles de comprensión de las tablas en alumnos de primaria y secundaria. Cult. Educ. 2010, 22, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mila, M.; Marti, E.; Gilabert, S.; Catells, M. Fifth through eight grade students’ difficulties in constructing bar graphs: Data organisation, data aggregation, and integration of a second variable. Math. Think. Learn. 2015, 16, 201–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martí, E. Tables as cognitive tools in primary education. In Representational Systems and Practices as Learning Tools in Different Fields of Learning; Andersen, C., Scheuer, N., Pérez Echeverría, M.P., Teubal, E., Eds.; Sense: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallauta, J.D.; Arteaga, P.; Garzón-Guerrero, J.A. Secondary School Students’ Construction and Interpretation of Statistical Tables. Mathematics 2021, 9, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.V. High school students interpreting tables and graphs: Implications for research. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2006, 4, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhateeb, M. The language used in the 8th grade mathematics textbook. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2019, 15, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhu, Y.; Miao, Z. Textbook research in mathematics education: Development status and directions. ZDM 2013, 45, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, T. The contextualized situations constructed for the use of statistics by school mathematics textbooks. Stat. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 18, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbel-Eisenmann, B.A. From intended curriculum to written curriculum: Examining the voice of a mathematics textbook. J. Res. Math. Educ. 2007, 38, 344–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasnovic, D. Requirements in mathematics textbooks: A five-dimensional analysis of textbook exercises and examples. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 49, 1003–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L.; Jacobbe, T. An analysis of the statistical content in textbooks for prospective elementary teachers. J. Stat. Educ. 2014, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haggarty, L.; Pepin, B. An investigation of mathematics textbooks and their use in English, French, and German classrooms: Who gets an opportunity to learn what? Br. Educ. Res. J. 2002, 28, 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, V.; Godino, J.D. La noción de configuración epistémica como herramienta de análisis de textos matemáticos: Su uso en la formación de profesores. Educ. Math. Pesqui. 2006, 8, 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- Godino, J.D.; Batanero, C.; Font, V. The onto-semiotic approach: Implications for the prescriptive character of didactics. Learn. Math. 2019, 39, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Levicoy, D.; Morales, R.; Arteaga, P.; López-Martín, M.M. Conocimiento sobre tablas estadísticas por estudiantes chilenos de tercer año de Educación Primaria. Educ. Math. 2020, 32, 247–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahanier-Reuter, D. Différents types de tableaux dans l’enseignement des statistiques. Spirale-Rev. Rech. Educ. 2003, 32, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, P. Evaluación de Conocimientos Sobre Gráficos Estadísticos y Conocimientos Didácticos en Futuros Profesores. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pallauta, J.D.; Arteaga, P. Niveles de complejidad semiótica en gráficos y tablas estadísticas. Números 2021, 106, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pallauta, J.D.; Batanero, C.; Gea, M.M. Complejidad semiótica de las tablas estadísticas en textos escolares chilenos y españoles de educación primaria. Teia Revista Educação Matemática Tecnológica Iberoamericana 2021, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. PISA 2018 Assessment and Analytical Framework: Science, Reading, Mathematics and Financial Literacy; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin. Semiologie Graphique; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bernabeu, J.; González, Y.; Garín, M.; Nieco, M.; Pérez, B.; García, M.; Pérez, M.N.; Morales, F.; Vidal, J.M.; Bellido, A. Matemáticas 6 Primaria. Más Savia; SM: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rosales, E.M.; Rodríguez, P.; Romero, M. Conocimiento, demanda cognitiva y contextos en la evaluación de la alfabetización científica en PISA. Eureka 2020, 17, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmartí, N.; Márquez, C. Aprendizaje de las ciencias basado en proyectos: Del contexto a la acción. Ápice 2017, 1, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wijaya, A.; van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, M.; Doorman, M.; Robitzsch, A. Difficulties in solving context-based PISA mathematics tasks: An analysis of students’ errors. Math. Enthus. 2014, 11, 555–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehmer, D.; Ryve, A.; Van Steenbrugge, H. Problem solving in Swedish mathematics textbooks for upper secondary school. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 60, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, H.C.; Stacey, K.; Schmidt, W.H. Science and mathematics literacy: PISA for better school education. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2018, 16, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gattuso, L.; Ottaviani, M.G. Complementing mathematical thinking and statistical thinking in school mathematics. In Teaching Statistics in School Mathematics—Challenges for Teaching and Teacher Education; Batanero, C., Burrill, G., Reading, C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 2011; pp. 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheaffer, R.L. Statistics and quantitative literacy. In Quantitative Literacy: Why Numeracy Matters for Schools and Colleges; Madison, B.L., Steen, L.A., Eds.; National Council on Education and the Disciplines: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Levicoy, D.; Morales, R.; López-Martín, M.M. Tablas estadísticas en libros de texto chilenos de 1º y 2º año de educación primaria. Revista Paranaense Educação Matemática 2015, 4, 10–39. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Levicoy, D.; Vásquez, C.; Molina-Portillo, E. Estudio exploratorio sobre tablas estadísticas en libros de texto de tercer año de educación primaria. Tangram 2018, 1, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, J.; Díaz-Levicoy, D.; Vidal, H.; Arredondo, E. Las tablas estadísticas en libros de texto de educación primaria en México. Paradigma 2019, 40, 153–175. [Google Scholar]

- Pallauta, J.D.; Gea, M.M.; Arteaga, P. Caracterización de las tareas propuestas sobre tablas estadísticas en libros de texto chilenos de educación básica. Paradigma 2021, 40, 32–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council for Education and Sport in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/educacion/portals/web/becas-y-ayudas/gratuidad-de-libros (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- Drisko, J.W.; Maschi, T. Content Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf, K. The Content Analysis Guidebook; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Estrella, S.; Estrella, P. Representaciones de datos en estadística: De listas a tablas. Revista Chilena Educación Matemática 2020, 12, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, S.; Jones, G.; Thornton, C.; Langrall, C.; Mooney, E. Children’s representation and organisation of data. Math. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 15, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, L.; Gómez, J.M.; Martín, P.; Quevedo, V.J. Matemáticas 3. Pieza a Pieza; Anaya: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal, A.I.; Ferrero, L.; Gómez, J.M.; Martín, P.; de la Rosa, L.I. Matemáticas 6. Pieza a Pieza; Anaya: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bernabeu, J.; Garín, M.; Modrego, R. Matemáticas 1 Primaria. Más Savia; SM: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Friel, S.; Curcio, F.; Bright, G. Making sense of graphs: Critical factors influencing comprehension and instructional implications. J. Res. Math. Educ. 2001, 32, 124–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernabeu, J.; Garín, M.; de Casacuberta, A.; Cusó, M.; Pérez, M.N.; Morales, F.; Vidal, J.M.; Valvanera, A. Matemáticas 3 Primaria. Más Savia; SM: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal, A.I.; de la Rosa, L.I. Matemáticas 2. Pieza a Pieza; Anaya: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alsina, Á.; Annexa, E. Estadística en contexto: Desarrollando un enfoque escolar común para promover la alfabetización. Tangram 2021, 4, 71–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Muñiz, L.J.; Muñiz-Rodríguez, L.; Vásquez, C.; Alsina, Á. ¿Cómo promover la alfabetización estadística y de datos en contexto? Estrategias y recursos a partir de la COVID-19 para Educación Secundaria. Números 2020, 104, 217–238. [Google Scholar]

| Type of Table | Grade | Total n = 405 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 n = 35 | 2 n = 20 | 3 n = 86 | 4 n = 80 | 5 n = 103 | 6 n = 81 | |||

| Data table | 34.3 | 5.0 | 24.4 | 8.8 | 17.5 | 18.5 | 18.3 | |

| One variable distribution | Counting | 10.0 | 24.4 | 20.0 | 3.7 | 10.4 | ||

| Frequency | 14.3 | 20.0 | 45.3 | 38.8 | 82.5 | 76.5 | 55.8 | |

| Grouped data | 3.8 | 1.2 | 1.0 | |||||

| Two-way table | 51.4 | 65.0 | 5.8 | 28.8 | 14.6 | |||

| Type of Table | Editorial | Total n = 405 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaya n = 179 | SM n = 226 | |||

| Data table | 12.3 | 23.0 | 18.3 | |

| One variable distribution | Counting | 17.9 | 4.4 | 10.4 |

| Frequency | 58.1 | 54.0 | 55.8 | |

| Grouped data | 0.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 | |

| Two-way table | 11.2 | 17.3 | 14.6 | |

| Activity Type | Grade | Total n = 405 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 n = 35 | 2 n = 20 | 3 n = 86 | 4 n = 80 | 5 n = 103 | 6 n = 81 | ||

| A1. Reading | 68.6 | 60.0 | 53.5 | 55.0 | 44.7 | 29.6 | 48.4 |

| A2. Completing | 8.6 | 5.0 | 9.3 | 12.5 | 4.9 | 7.4 | 8.1 |

| A3. Building a table | 2.9 | 10.0 | 14.0 | 11.3 | 14.6 | 12.3 | 12.1 |

| A4. Calculating | 10.7 | 21.0 | 6.9 | ||||

| A5. Translating to a graph | 5.7 | 20.0 | 11.6 | 11.3 | 15.5 | 16.0 | 13.3 |

| A6. Inventing | 3.5 | 0.7 | |||||

| A7. Registering data | 5.7 | 5.0 | 2.3 | 5.0 | 5.8 | 2.5 | 4.2 |

| A8. Reasoning | 8.6 | 5.8 | 5.0 | 3.9 | 11.1 | 6.2 | |

| Activity Type | Editorial | Total n = 405 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anaya n = 179 | SM n = 226 | ||

| A1. Reading | 50.3 | 46.9 | 48.4 |

| A2. Completing | 5.6 | 10.2 | 8.1 |

| A3. Building a table | 13.4 | 11.1 | 12.1 |

| A4. Calculating | 9.5 | 4.9 | 6.9 |

| A5. Translating to a graph | 12.3 | 14.2 | 13.3 |

| A6. Inventing | 1.3 | 0.7 | |

| A7. Registering data | 1.7 | 6.2 | 4.2 |

| A8. Reasoning | 7.3 | 5.3 | 6.2 |

| Context Type | Grade | Total n = 405 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 n = 35 | 2 n = 20 | 3 n = 86 | 4 n = 80 | 5 n = 103 | 6 n = 81 | ||

| Personal | 85.7 | 95.0 | 62.8 | 83.8 | 65.0 | 64.2 | 71.4 |

| Social | 5.0 | 23.3 | 11.3 | 1.9 | 3.7 | 8.6 | |

| Occupational | 14.0 | 5.0 | 5.8 | 9.9 | 7.4 | ||

| Scientific | 10.7 | 12.3 | 5.2 | ||||

| Random experiment | 14.3 | 16.5 | 9.9 | 7.4 | |||

| Context Type | Editorial | Total n = 405 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anaya n = 179 | SM n = 226 | ||

| Personal | 70.9 | 71.7 | 71.4 |

| Social | 7.3 | 9.7 | 8.6 |

| Occupational | 14.5 | 1.8 | 7.4 |

| Scientific | 3.9 | 6.2 | 5.2 |

| Random experiment | 3.4 | 10.6 | 7.4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gea, M.M.; Pallauta, J.D.; Batanero, C.; Valenzuela-Ruiz, S.M. Statistical Tables in Spanish Primary School Textbooks. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2809. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10152809

Gea MM, Pallauta JD, Batanero C, Valenzuela-Ruiz SM. Statistical Tables in Spanish Primary School Textbooks. Mathematics. 2022; 10(15):2809. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10152809

Chicago/Turabian StyleGea, María M., Jocelyn D. Pallauta, Carmen Batanero, and Silvia M. Valenzuela-Ruiz. 2022. "Statistical Tables in Spanish Primary School Textbooks" Mathematics 10, no. 15: 2809. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10152809

APA StyleGea, M. M., Pallauta, J. D., Batanero, C., & Valenzuela-Ruiz, S. M. (2022). Statistical Tables in Spanish Primary School Textbooks. Mathematics, 10(15), 2809. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10152809