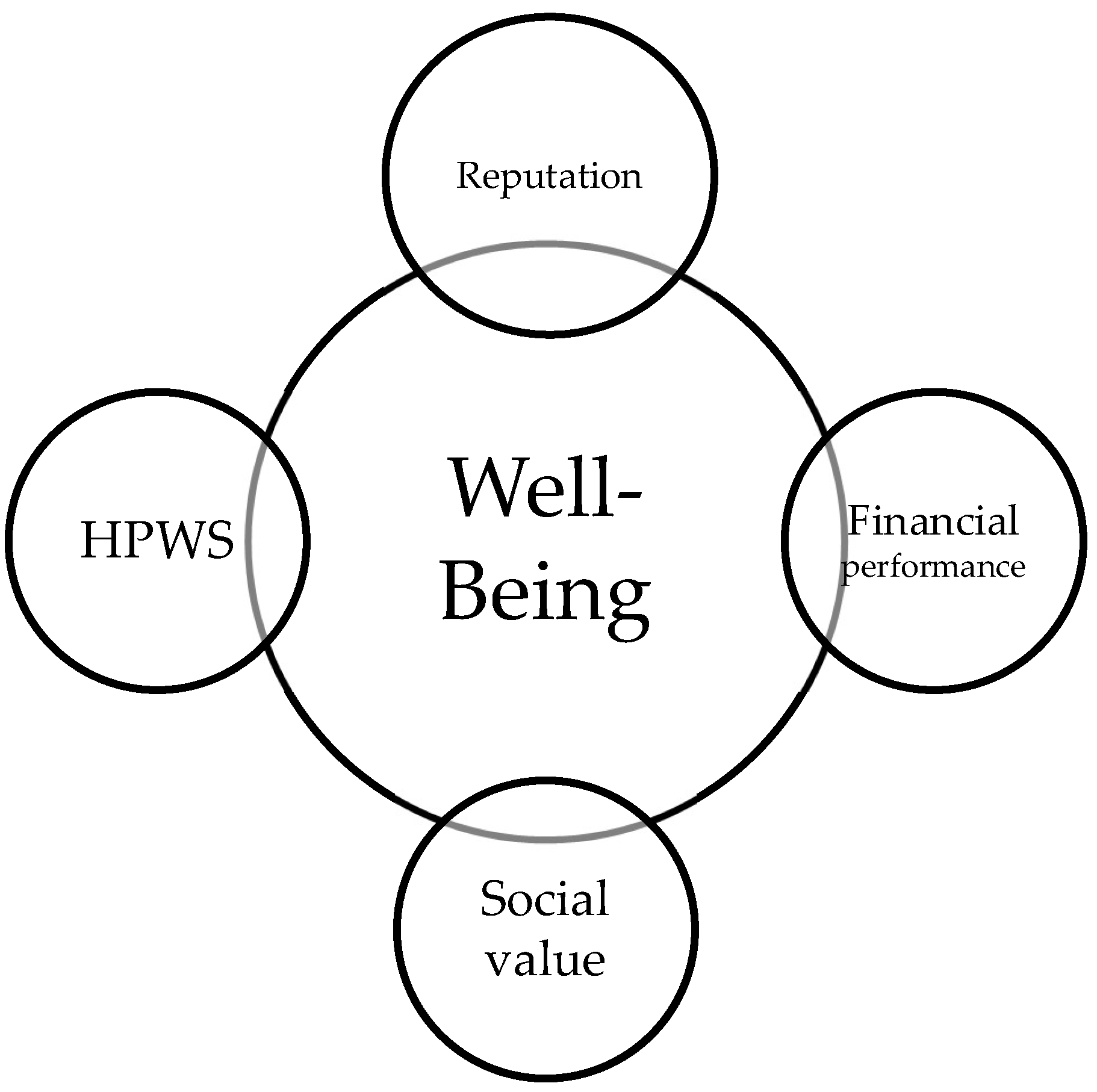

Creating Financial and Social Value by Improving Employee Well-Being: A PLS-SEM Application in SMEs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Well-Being and High-Performance Work Systems

2.2. High-Performance Work Systems and Financial Performance

2.3. Well-Being, Social Value, and Financial Performance

2.4. Corporate Reputation and Mediating Effect

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Population and Sample

3.2. Measuring Instrument

3.3. Measuring Indicators

4. PLS-SEM

5. Results

5.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

5.2. Discriminant Validity

5.3. Structural Model Evaluation

5.3.1. Variance Inflation Factor

5.3.2. Endogeneity

5.4. Validation of the Hypothesis

5.5. Predictive Relevance of the Model

6. Discussion of Results

7. Conclusions

8. Future Lines and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bandura, A. Social foundations of thought and action: A Social-Cognitive View. In The Health Psychology Reader; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 94–106. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 55, pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M.; Christianson, M.K.; Price, R.H. Happiness, health, or relationships? Managerial practices and employee well-being tradeoffs. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peccei, R.; Van De Voorde, K.; Van Veldhoven, M. HRM well-being and performance: A theoretical and empirical review. HRM Perform. Achiev. Chall. 2013, 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlstrom, D. The hidden reason why the First World War matters today: The development and spread of modern management. Brown J. World Aff. 2014, 21, 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Van De Voorde, K.; Paauwe, J.; Van Veldhoven, M. Employee well-being and the HRM–organizational performance relationship: A review of quantitative studies. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babic, A.; Stinglhamber, F.; Hansez, I. High-Performance Work Systems and Well-Being: Mediating Role of Work-to-Family Interface. Psychol. Belg. 2019, 59, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wood, S.; De Menezes, L.M. High involvement management, high-performance work systems and well-being. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. Manag. 2011, 22, 1586–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihail, D.M.; Kloutsiniotis, P.V. The effects of high-performance work systems on hospital employees’ work-related well-being: Evidence from Greece. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, C.J.; Dowling, P.J.; Bartram, T. Exploring the effects of high-performance work systems (HPWS) on the work-related well-being of Chinese hospital employees. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. Manag. 2013, 24, 3196–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, K.S.; Holahan, C.K.; Gottlieb, N.H. Employee involvement management practices, work stress, and depression in employees of a human services residential care facility. Hum. Relat. 2001, 54, 1065–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macky, K.; Boxall, P. High-involvement work processes, work intensification and employee well-being: A study of New Zealand worker experiences. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2018, 46, 38–55. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg, R.J.; Richardson, H.A.; Eastman, L.J. The impact of high involvement work processes on organizational effectiveness: A second-order latent variable approach. Group Organ. Manag. 1999, 24, 300–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P.; Macky, K. High-involvement work processes, work intensification and employee well-being. Work Employ Soc. 2014, 28, 963–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.C.; Ahlstrom, D.; Lee, A.Y.P.; Chen, S.Y.; Hsieh, M.J. High performance work systems, employee well-being, and job involvement: An empirical study. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Cao, Y. High-performance work system, work well-being, and employee creativity: Cross-level moderating role of transformational leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, W.; Nawakitphaitoon, K.; Huang, W.; Harney, B.; Gollan, P.J.; Xu, C.Y. Towards better work in China: Mapping the relationships between high-performance work systems, trade unions, and employee well-being. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2019, 57, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Meng, Y. High-performance work systems and employee engagement: Empirical evidence from China. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2018, 56, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlstrom, D.; Chen, S.J.; Yeh, K.S. Managing in ethnic Chinese communities: Culture, institutions, and context. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2010, 27, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riordan, C.M.; Vandenberg, R.J.; Richardson, H.A. Employee involvement climate and organizational effectiveness. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 44, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Martín, I.; Bou-Llusar, J.C. Examining the intermediate role of employee abilities, motivation and opportunities to participate in the relationship between HR bundles and employee performance. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2018, 21, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonnaya, C.; Daniels, K.; Connolly, S.; van Veldhoven, M. Integrated and isolated impact of high-performance work practices on employee health and well-being: A comparative study. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macky, K.; Boxall, P. The relationship between ‘high-performance work practices’ and employee attitudes: An investigation of additive and interaction effects. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. Manag. 2007, 18, 537–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.M.; Patel, P.C.; Messersmith, J.G. High-performance work systems and job control: Consequences for anxiety, role overload, and turnover intentions. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 1699–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paré, G.; Tremblay, M. The influence of high-involvement human resources practices, procedural justice, organizational commitment, and citizenship behaviors on information technology professionals’ turnover intentions. Group Organ. Manag. 2007, 32, 326–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitener, E.M. Do “high commitment” human resource practices affect employee commitment? A cross-level analysis using hierarchical linear modeling. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 515–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danford, A.; Richardson, M.; Stewart, P.; Tailby, S.; Upchurch, M. Partnership, high performance work systems and quality of working life. New Technol. Work Employ. 2008, 23, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Truss, C. Complexities and controversies in linking HRM with organizational outcomes. J. Manag. Stud. 2001, 38, 1121–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Hill, S.; McGovern, P.; Mills, C.; Smeaton, D. ‘High-performance’management practices, working hours and work–life balance. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2003, 41, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrnrooth, M.; Björkman, I. An integrative HRM process theorization: Beyond signalling effects and mutual gains. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1109–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, B.; Voorde, K.V.D.; Veldhoven, M.V. Cross-level effects of high-performance work practices on burnout: Two counteracting mediating mechanisms compared. Pers. Rev. 2009, 38, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Green, F. Why has work effort become more intense? Ind. Relat. A J. Econ. Soc. 2004, 43, 709–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Datta, D.K.; Guthrie, J.P.; Wright, P.M. Human resource management and labor productivity: Does industry matter? Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zacharatos, A.; Barling, J.; Iverson, R.D. High-performance work systems and occupational safety. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.B. Effects of human resource systems on manufacturing performance and turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 670–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.P. High-involvement work practices, turnover, and productivity: Evidence from New Zealand. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huselid, M.A. The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 635–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, E.E., III. The Ultimate Advantage: Creating the High-Involvement Organization; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J.; Jeffrey, P. The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Batt, R.; Valcour, P.M. Human resources practices as predictors of work-family outcomes and employee turnover. Ind. Relat. A J. Econ. Soc. 2003, 42, 189–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B.E.; Huselid, M.A. High performance work systems and firm performance: A synthesis of research and managerial implications. In Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management; JAI Press: Stamford, 1998; Volume 16, pp. 53–101. [Google Scholar]

- Meddour, H.; Majid, A.H.A.; Abdussalaam, I.I. Mediating effect of employee creativity on the Relationship between HPWS and firm performance. In Proceedings of the E-Proceeding of the International Conference on Economics, Entrepreneurship and Management, Lagkawi, Malasia, 6 July 2019; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Godard, J. Beyond the high-performance paradigm? An analysis of variation in Canadian managerial perceptions of reform programme effectiveness. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2001, 39, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, R.D.; Zatzick, C.D. High-commitment work practices and downsizing harshness in Australian workplaces. Ind. Relat. A J. Econ. Soc. 2007, 46, 456–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepak, D.P.; Liao, H.; Chung, Y.; Harden, E.E. A conceptual review of human resource management systems in strategic human resource management research. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 25, 217–271. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E. Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Wright, T.A. When a” happy” worker is really a” productive” worker: A review and further refinement of the happy-productive worker thesis. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2001, 53, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrick, D.D. What leaders need to know about organizational culture. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.D. Why do lay people believe that satisfaction and performance are correlated? Possible sources of a commonsense theory. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 753–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galabova, L.; McKie, L. “The five fingers of my hand”: Human capital and well-being in SMEs. Pers. Rev. 2013, 42, 662–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taris, T.W.; Schreurs, P.J. Well-being and organizational performance: An organizational-level test of the happy-productive worker hypothesis. Work Stress 2009, 23, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delery, J.E. Issues of fit in strategic human resource management: Implications for research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1998, 8, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messersmith, J.G.; Patel, P.C.; Lepak, D.P.; Gould-Williams, J.S. Unlocking the black box: Exploring the link between high-performance work systems and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Purcell, J.; Kinnie, N. HRM and business performance. In Oxford Handbook of Human Resource Management; Boxall, P.F., Purcell, J., Wright, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 533–551. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, R.; Lepak, D.P.; Wang, H.; Takeuchi, K. An empirical examination of the mechanisms mediating between high-performance work systems and the performance of Japanese organizations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deephouse, D.L. Media reputation as a strategic resource: An integration of mass communication and resource-based theories. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 1091–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsbach, K.D.; Kramer, R.M. Members’ responses to organizational identity threats: Encountering and countering the Business Week rankings. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 442–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fombrun, C.; Shanley, M. What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J. Realizing Value from the Corporate Image; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R. The strategic analysis of intangible resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 1992, 13, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. A framework linking intangible resources and capabilities to sustainable competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.L. The very visible hand of reputational rankings in US business schools. Corp. Reput. Rev. 1998, 1, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deephouse, D.L.; Carter, S.M. An examination of differences between organizational legitimacy and organizational reputation. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 329–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, B.; Esteban, Á.; Gutiérrez, S. Determinants of reputation of leading Spanish financial institutions among their customers in a context of economic crisis. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2014, 17, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stigler, G.J. Information in the labor market. J. Polit. Econ. 1962, 70, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism: Firms, Markets, Relational Contracting; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Love, E.G.; Kraatz, M. Character, conformity, or the bottom line? How and why downsizing affected corporate reputation. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 314–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, X.; Pittman, J.; Rui, O. Reputational implications for partners after a major audit failure: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kölbel, J.F.; Busch, T.; Jancso, L.M. How media coverage of corporate social irresponsibility increases financial risk. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 2266–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetin, V.H.; Knowles, L.L.; Summey, J.H.; McQueen, K.S. Willingness-to-punish the corporate brand for corporate social irresponsibility. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1822–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardella, G.; Brammer, S.; Surdu, I. Shame on who? The effects of corporate irresponsibility and social performance on organizational reputation. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 31, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Rindova, V. Who’s tops and who decides? The social construction of corporate reputations. New York Univ. Stern Sch. Bus. Work. Pap. 1996, 5, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, D.; Lee, P.M.; Dai, Y. Organizational reputation: A review. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 153–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turban, D.B.; Cable, D.M. Firm reputation and applicant pool characteristics. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2003, 24, 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.P.; El-Akremi, A.; Igalens, J.; Swaen, V. Corporate social responsibility influence on employees. Int. Center Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2010, 54, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D. The Impact of Employees’ Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility on Job Attitudes and Behaviors: A Study in China. Ph.D. Thesis, Singapore Management University, Singapore, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan, K.; Money, K.; Downing, S.; Hillenbrand, C. Reputation in relationships: Measuring experiences, emotions and behaviors. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2005, 8, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Money, K.; Hillenbrand, C. Using reputation measurement to create value: An analysis and integration of existing measures. J. Gen. Manag. 2006, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.J.; Pavelin, S. Corporate reputation and social performance: The importance of fit. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.L.F.; Sotorrío, L.L. The creation of value through corporate reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, I.C.; Callen, J.L.; Branco, M.C.; Curto, J.D. The value relevance of reputation for sustainability leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 119, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, T.; Dollinger, M. Target reputation and appropriability: Picking and deploying resources in acquisitions. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimov, D.; Shepherd, D.A.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Requisite expertise, firm reputation, and status in venture capital investment allocation decisions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cable, D.M.; Graham, M.E. The determinants of job seekers’ reputation perceptions. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 929–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staw, B.M.; Epstein, L.D. What bandwagons bring: Effects of popular management techniques on corporate performance, reputation, and CEO pay. Adm. Sci. Q. 2000, 45, 523–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.W.; Dowling, G.R. Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.R.; Eden, L.; Li, D. CSR reputation and firm performance: A dynamic approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazy, J.K.; Moskalev, S.A.; Torras, M. Toward a theory of social value creation: Individual agency and the use of information within nested dynamical systems. In Complexity Science and Social Entrepreneurship: Adding Social Value through Systems Thinking; ISCE Publishing: Mansfield, UK, 2009; pp. 257–284. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, R.L.; Murray, P.C.; Mellor, R. Strategic quality management and financial performance indicators. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 1997, 14, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvin, D. Managing Quality: The Strategic and Competitive Edge; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Marinič, P. Customer Satisfaction and Financial Performance. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Science and Arts SGEM, Tirana, Albania, 24–30 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Auerswald, P.E. Creating social value. In Stanford Social Innovation Review; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Institute. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_Candcid=1254736160707andmenu=ultiDatosandidp=1254735576550 (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Zhang, B.; Morris, J.L. High-performance work systems and organizational performance: Testing the mediation role of employee outcomes using evidence from PR China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. Manag. 2014, 25, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichniowski, C.; Shaw, K.; Prennushi, G. The effects of human resource practices on manufacturing performance: A study of steel finishing lines. Am. Econ. Rev. 1997, 87, 291–313. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.E.; Schuler, R.S. Understanding human resource management in the context of organizations and their environments. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 1995, 46, 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDuffie, J.P. Human resource bundles and manufacturing performance: Organizational logic and flexible production systems in the world auto industry. Ilr Rev. 1995, 48, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, P.; Roberts, J. Complementarities and fit strategy, structure, and organizational change in manufacturing. J. Account. Econ. 1995, 19, 179–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J. Competitive Advantage through People: Unleashing the Power of the Workforce; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Guerci, M.; Hauff, S.; Gilardi, S. High performance work practices and their associations with health, happiness and relational well-being: Are there any tradeoffs? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. Manag. 2019, 33, 329–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huselid, M.A.; Becker, B.E. The impact high performance work systems, implementation effectiveness, and alignment with strategy on shareholder wealth. In Academy of Management; Briarcliff Manor: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 1, pp. 144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer–company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De los Ríos Berjillos, A.; Lozano, M.R.; Valencia, P.T.; Ruz, M.C. Una aproximación a la relación entre información sobre la responsabilidad social orientada al cliente y la reputación corporativa de las entidades financieras españolas. Cuad. Econ. Dir. Empres. 2012, 15, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, H.C.; Parc, J.; Yim, S.H.; Park, N. An extension of Porter and Kramer’s creating shared value (CSV): Reorienting strategies and seeking international cooperation. J. Int. Area Stud. 2011, 18, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Vaidyanathan, L.; Scott, M. Creating shared value in India: The future for inclusive growth. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2012, 37, 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Juscius, V.; Jonikas, D. Integration of CSR into value creation chain: Conceptual framework. Eng. Econ. 2013, 24, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, P.L.; Little, B.L. Do perceptions of corporate social responsibility contribute to explaining differences in corporate price-earnings ratios? A research note. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2000, 3, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, C. Consumer information, product quality, and seller reputation. Bell J. Econ. 1982, 13, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, C. Premiums for high quality products as returns to reputations. Q. J. Econ. 1983, 98, 659–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Valdez-Juárez, L.E.; Castuera-Díaz, Á.M. Corporate social responsibility as an antecedent of innovation, reputation, performance, and competitive success: A multiple mediation analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Vandenberg, R.J.; Edwards, J.R. 12 structural equation modeling in management research: A guide for improved analysis. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2009, 3, 543–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill Jr, G.A. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Gupta, S. Handling endogenous regressors by joint estimation using copulas. Mark. Sci. 2012, 31, 567–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Proksch, D.; Ringle, C.M. Revisiting Gaussian copulas to handle endogenous regressors. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; and Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modelling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modelling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, M. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1974, 36, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisser, S. The predictive sample reuse method with applications. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1975, 70, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, J.; McNeil, N.; Bartram, T. The Australian Men’s Sheds movement: Human resource management in a voluntary organisation. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2013, 51, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farndale, E.; Hope-Hailey, V.; Kelliher, C. High commitment performance management: The roles of justice and trust. Pers. Rev. 2011, 40, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, L.Y.; Aryee, S.; Law, K.S. High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: A relational perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, S.A. High performance work systems and intermediate indicators of firm performance within the US small business sector. J. Manag. 2002, 28, 765–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Law, K.S.; Chang, S.; Xin, K.R. Human resources management and firm performance: The differential role of managerial affective and continuance commitment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.Q.; Lau, C.M. High performance work systems and performance: The role of adaptive capability. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 1487–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.S.; Chambel, M.J. Work-to-family enrichment and employees’ well-being: High performance work system and job characteristics. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 119, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Voorde, K.; Beijer, S. The role of employee HR attributions in the relationship between high-performance work systems and employee outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2015, 25, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoian, C.; Gilman, M. Corporate social responsibility that “pays”: A strategic approach to CSR for SMEs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2017, 55, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, K.P.; Prauschke, C. Intangible Assets and Corporate Reputation-Conceptual Relationships and Implications for Corporate Practice’. J. General Manag. 2006, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, J.; Stackhouse, M.; Osiyevskyy, O. I love that company: Look how ethical, prominent, and efficacious it is—A triadic organizational reputation (TOR) Scale. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 889–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, D. (Ed.) Employment Regimes and the Quality of Work; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Huete-Alcocer, N.; López-Ruiz, V.R.; Alfaro-Navarro, J.L.; Nevado-Peña, D. European Citizens’ Happiness: Key Factors and the Mediating Effect of Quality of Life, a PLS Approach. Mathematics 2022, 10, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Indicators | Loads (λ) | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPWS | 0.886 | 0.908 | 0.524 | ||

| Employee participation in decision making | HPWS_2 | 0.757 | |||

| Professional career | HPWS_3 | 0.819 | |||

| Selective Hiring | HPWS_4 | 0.721 | |||

| Investment in training | HPWS_5 | 0.775 | |||

| Continuous training | HPWS_6 | 0.748 | |||

| Employee information | HPWS_7 | 0.638 | |||

| Performance evaluation & feedback | HPWS_8 | 0.673 | |||

| Pay Equity | HPWS_9 | 0.718 | |||

| Contingent Compensation | HPWS_10 | 0.648 | |||

| WELL-BEING | 0.758 | 0.890 | 0.803 | ||

| Motivation of workers | WB_1 | 0.923 | |||

| Work absenteeism | WB_2 | 0.868 | |||

| REPUTATION | 0.843 | 0.927 | 0.865 | ||

| Positive image and reputation | REP_1 | 0.931 | |||

| Transparency | REP_2 | 0.929 | |||

| SOCIAL VALUE | 0.845 | 0.895 | 0.681 | ||

| Quality of the products | SV_1 | 0.783 | |||

| Efficiency of the processes | SV_2 | 0.820 | |||

| Customer satisfaction | SV_3 | 0.863 | |||

| Rapid anticipation of environmental changes | SV_4 | 0.835 | |||

| FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE | 0.847 | 0.929 | 0.867 | ||

| Business growth | FP_2 | 0.928 | |||

| Profitability | FP_4 | 0.934 |

| Financial Perform | HPWS | Reputation | Social Value | Well-Being | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FINANCIAL PERFOR | 0.931 | ||||

| HPWS | 0.388 | 0.724 | |||

| REPUTATION | 0.385 | 0.425 | 0.930 | ||

| SOCIAL VALUE | 0.642 | 0.458 | 0.394 | 0.826 | |

| WELL-BEING | 0.612 | 0.491 | 0.386 | 0.665 | 0.896 |

| Indicators | Financial Perform | Social Value | Well-Being | Reputation | HPWS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP_2 | 0.928 | 0.588 | 0.556 | 0.340 | 0.342 |

| FP_4 | 0.934 | 0.607 | 0.583 | 0.376 | 0.381 |

| SV_1 | 0.430 | 0.783 | 0.458 | 0.303 | 0.352 |

| SV_2 | 0.563 | 0.820 | 0.531 | 0.293 | 0.367 |

| SV_3 | 0.523 | 0.863 | 0.600 | 0.357 | 0.375 |

| SV_4 | 0.586 | 0.835 | 0,591 | 0,346 | 0.415 |

| WB_1 | 0.623 | 0.643 | 0.923 | 0.365 | 0.516 |

| WB_2 | 0.455 | 0.541 | 0.868 | 0.325 | 0.346 |

| REP_1 | 0.374 | 0.374 | 0.354 | 0.931 | 0.390 |

| REP_2 | 0.341 | 0.359 | 0.364 | 0.929 | 0.400 |

| HPWS_2 | 0.247 | 0.304 | 0.333 | 0.270 | 0.757 |

| HPWS_3 | 0.300 | 0.351 | 0.363 | 0.296 | 0.819 |

| HPWS_4 | 0.302 | 0.329 | 0.375 | 0.306 | 0.721 |

| HPWS_5 | 0.305 | 0.363 | 0.363 | 0.333 | 0.775 |

| HPWS_6 | 0.282 | 0.330 | 0.356 | 0.294 | 0.748 |

| HPWS_7 | 0.375 | 0.378 | 0.457 | 0.415 | 0.638 |

| HPWS_8 | 0.231 | 0.304 | 0.301 | 0.282 | 0.673 |

| HPWS_9 | 0.208 | 0.325 | 0.322 | 0.300 | 0.718 |

| HPWS_10 | 0.194 | 0.238 | 0.233 | 0.176 | 0.648 |

| Gaussian Copula | p-Value |

|---|---|

| GC (HPWS)→ Financial value | 0.064 |

| GC (HPWS) → Reputation | 0.436 |

| GC (HPWS) → Well-being | 0.073 |

| GC (Reputation) → Financial value | 0.312 |

| GC (Reputation) → Social value | 0.742 |

| GC (Reputation) → Well-being | 0.424 |

| GC (Well-being) → Social value | 0.284 |

| Hypothesis | β Coefficients | t-Values | p-Values | Supported | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | HPWS–well-being | 0.399 | 12.735 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H2 | HPWS-financial performance | 0.015 | 0.524 | 0.600 | No |

| H3 | Well-being–social value | 0.665 | 29.006 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H4 | Well-being–financial performance | 0.302 | 7.192 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H5 | HPWS–reputation | 0.425 | 16.599 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H6 | Reputation–well-being | 0.217 | 6.545 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H7 | Reputation–financial performance | 0.107 | 3.480 | 0.001 | Yes |

| H8 | Social value–financial performance | 0.392 | 10.618 | 0.000 | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rubio-Andrés, M.; Ramos-González, M.d.M.; Gutiérrez-Broncano, S.; Sastre-Castillo, M.Á. Creating Financial and Social Value by Improving Employee Well-Being: A PLS-SEM Application in SMEs. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4456. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10234456

Rubio-Andrés M, Ramos-González MdM, Gutiérrez-Broncano S, Sastre-Castillo MÁ. Creating Financial and Social Value by Improving Employee Well-Being: A PLS-SEM Application in SMEs. Mathematics. 2022; 10(23):4456. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10234456

Chicago/Turabian StyleRubio-Andrés, Mercedes, Ma del Mar Ramos-González, Santiago Gutiérrez-Broncano, and Miguel Ángel Sastre-Castillo. 2022. "Creating Financial and Social Value by Improving Employee Well-Being: A PLS-SEM Application in SMEs" Mathematics 10, no. 23: 4456. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10234456