Advance Dynamic Panel Second-Generation Two-Step System Generalized Method of Movement Modeling: Applications in Economic Stability-Shadow Economy Nexus with a Special Case of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Economy of Saudi Arabia and the Shadow Economy

2. Literature Review

2.1. Taxation

2.2. Regulations

2.3. Government Expenditure

3. Data and Methodology

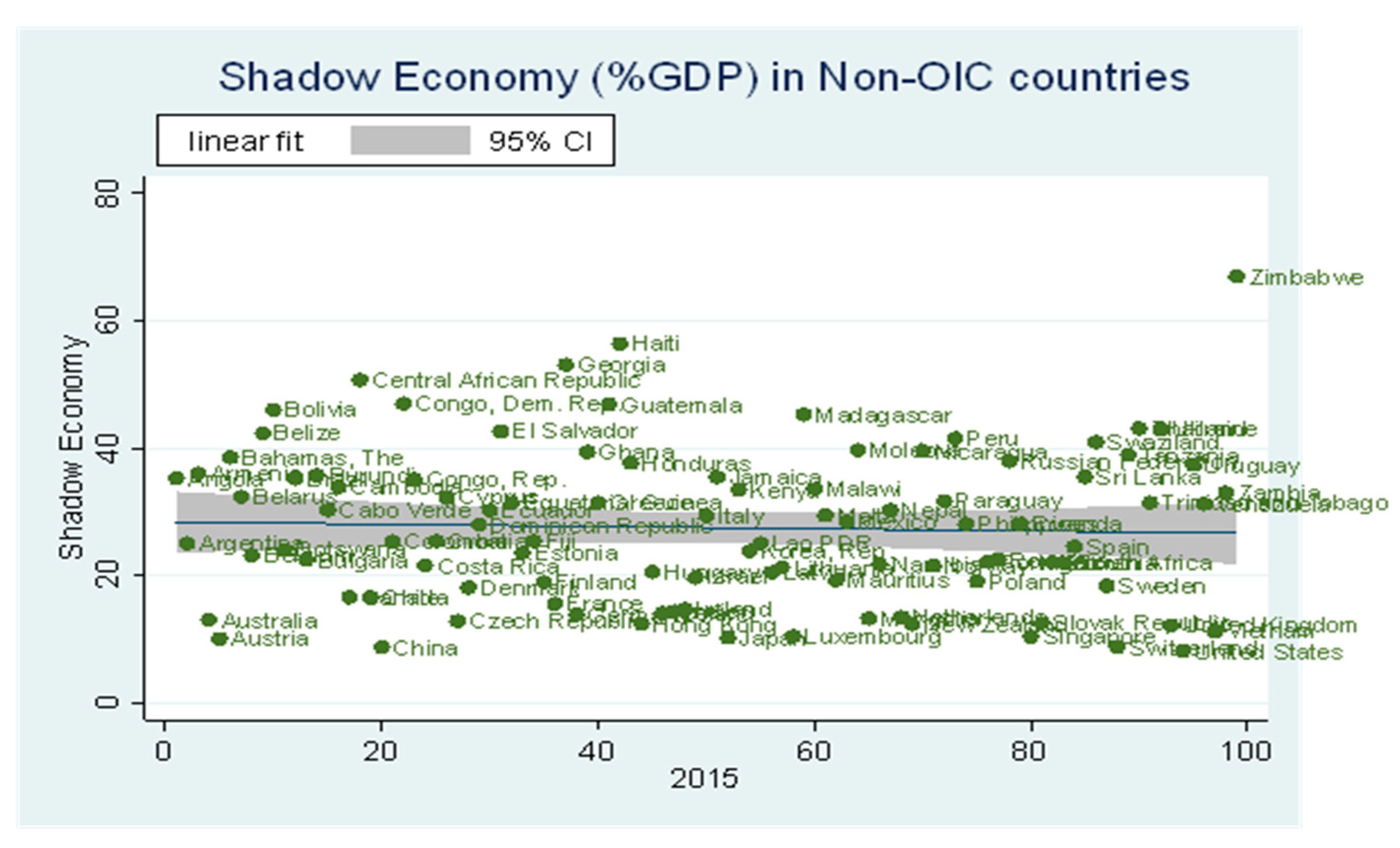

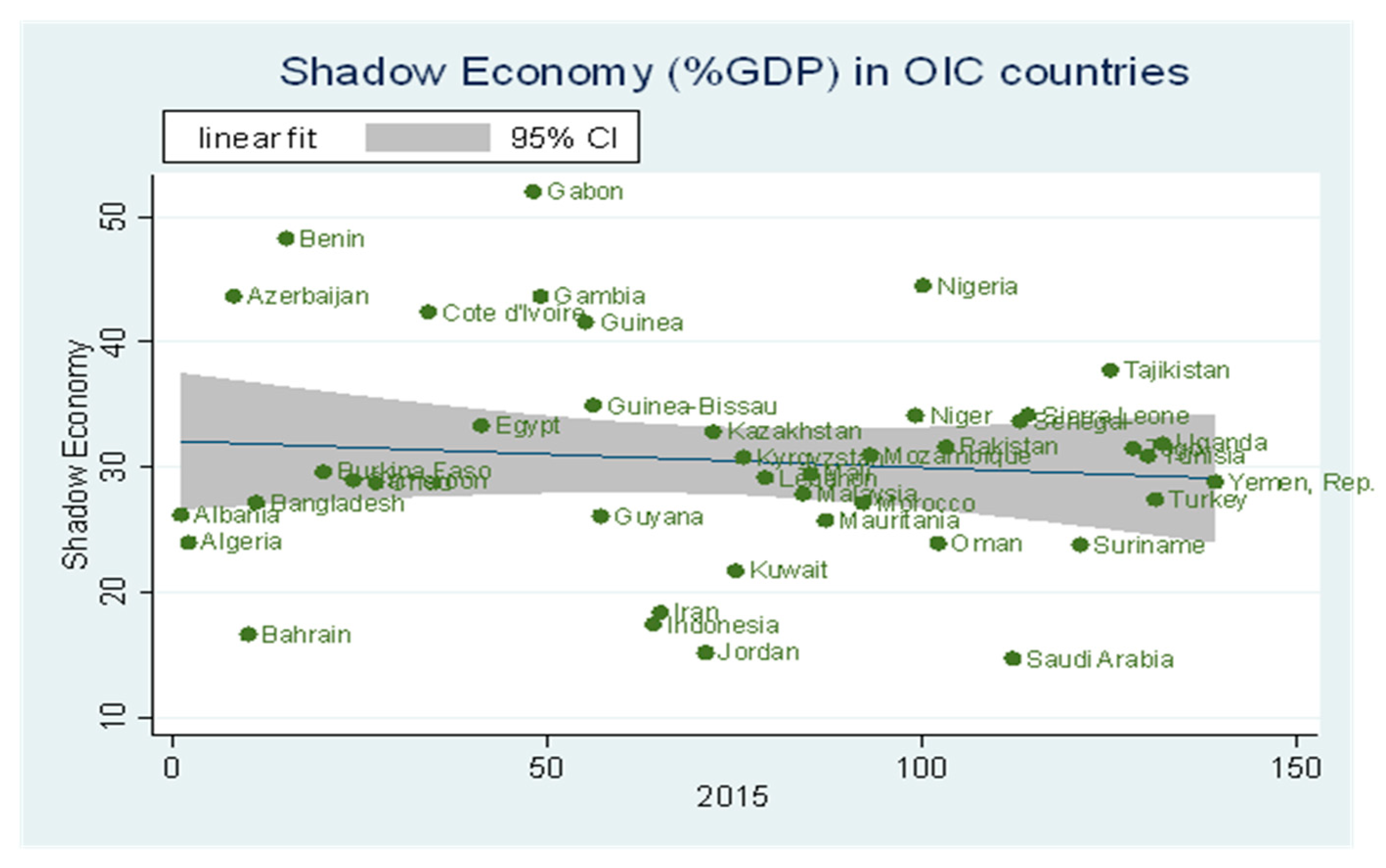

4. Results and Discussion

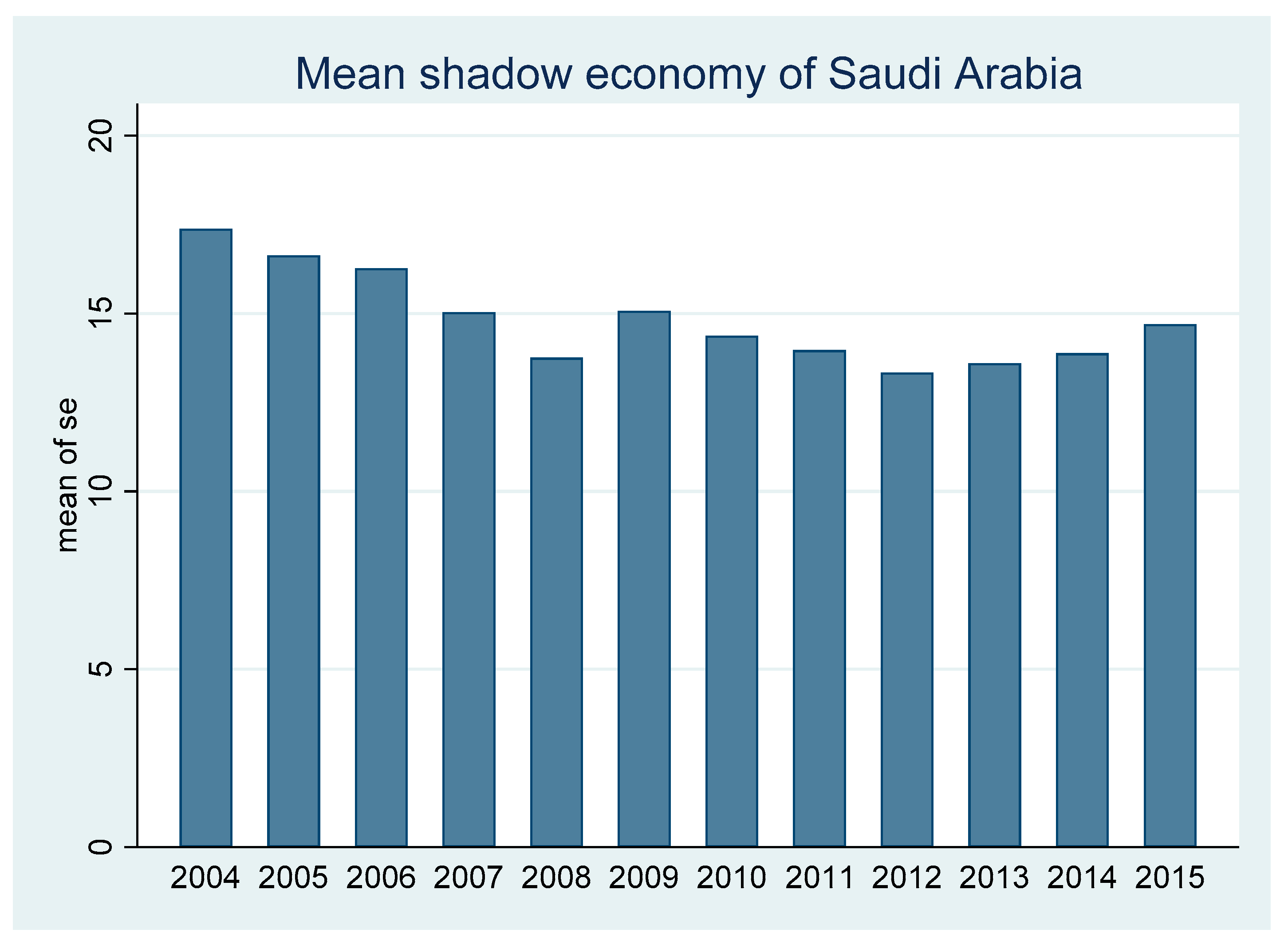

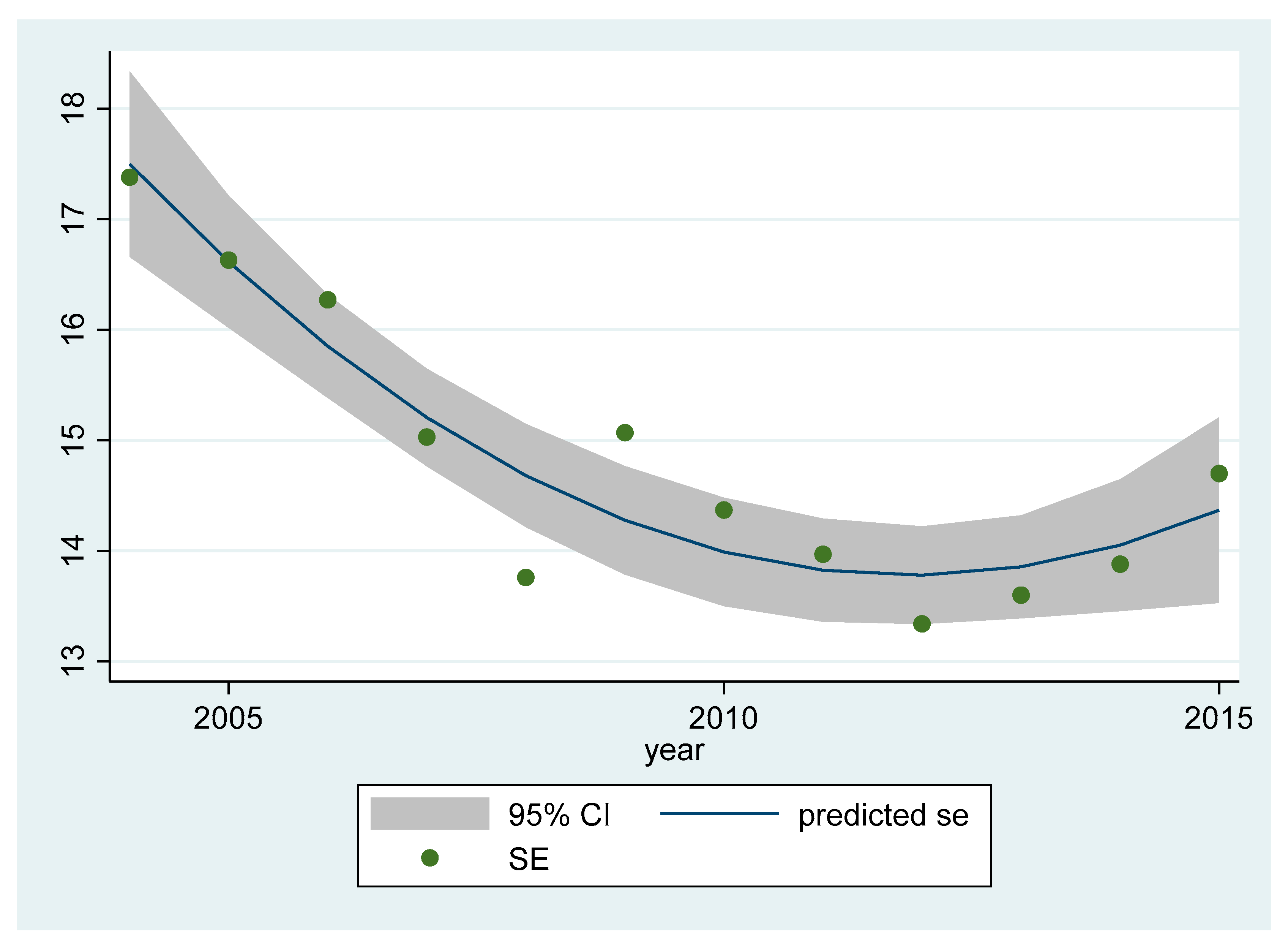

4.1. Shadow Economy in Saudi Arabia

4.2. Robustness Check

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Description | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product (Annual %) | World Development Indicators [12] |

| SDGDP | Standard Deviation of GDP | Own Calculation |

| SE | Shadow Economy (% of GDP) | Schneider and Medina [51] |

| T | Trade (% of GDP) | World Development Indicators [12] |

| TAXB | Tax (% of GDP) | World Development Indicators [12] |

| GE | Government Expenditure (% of GDP) | World Development Indicators [12] |

| FF | Financial freedom (percentile Rank) | The Heritage Foundation |

| ER | Real effective exchange rate index (2010 = 100) | World Development Indicators [12] |

| ROL | Rule of Law (Percentile Rank) | World Governance Indicators [12] |

| GCF | Gross capital formation (annual % growth) | World Governance Indicators [12] |

| INVF | Investment Freedom (Percentile Rank) | The Heritage Foundation |

| Edu | School enrollment, secondary (% gross) | World Governance Indicators [12] |

| PS | Political Stability (Percentile Rank) | World Governance Indicators [12] |

| U | Unemployment (% of Total Labor Force) | World Development Indicators [12] |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dep. Var. GDP/SDGDP | FE GDP | FE SDGDP | RE GDP | GMM GDP | GMM SDGDP |

| SE | −0.2285 ** | −0.0992 ** | −0.0335 * | −1.0567 ** | −0.3832 ** |

| [0.102] | [0.049] | [0.019] | [0.447] | [0.173] | |

| L.SDGDP | 0.5235 *** | ||||

| [0.085] | |||||

| L.GDP | 0.0045 | ||||

| [0.095] | |||||

| T | 0.0397 * | −0.0166 * | 0.0077 ** | 0.0534 * | 0.0221 ** |

| [0.021] | [0.010] | [0.003] | [0.029] | [0.008] | |

| TAXB | −0.0134 | −0.0070 | 0.0134 | −0.5450 *** | −0.1382 *** |

| [0.051] | [0.028] | [0.015] | [0.162] | [0.048] | |

| GE | −0.6506 *** | 0.0857 | −0.3291 *** | −2.0999 *** | −0.0217 |

| [0.188] | [0.072] | [0.042] | [0.547] | [0.164] | |

| FF | 0.0678 ** | 0.0152 | 0.0049 | 0.0342 | −0.0297 |

| [0.026] | [0.015] | [0.011] | [0.123] | [0.030] | |

| GCF | −0.0000 ** | ||||

| [0.000] | |||||

| EDU | −0.0126 | ||||

| [0.016] | |||||

| ER | −0.0835 *** | −0.0642 *** | −0.2505 * | −0.0137 | |

| [0.029] | [0.013] | [0.149] | [0.034] | ||

| PS | 0.0689 ** | −0.0138 | |||

| [0.031] | [0.009] | ||||

| ROL | −0.5609 ** | −0.2574 *** | |||

| [0.231] | [0.081] | ||||

| Constant | 18.303 ** | 6.1414 ** | 14.751 *** | 157.036 *** | 38.440 *** |

| [7.025] | [2.785] | [2.125] | [43.209] | [13.882] | |

| Observation | 973 | 1273 | 973 | 895 | 894 |

| R2 | 0.178 | 0.016 | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.172 | 0.011 | |||

| Instruments | 21 | 53 | |||

| Groups | 83 | 133 | 83 | 83 | 83 |

| AR (1) | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| AR (2) | 0.13 | 0.015 | |||

| Sargan | 0.13 | 0.00 | |||

| Hansen | 0.54 | 0.01 | |||

| F-Stats | 0.00 | 0.00 |

References

- Bitzenis, A.; Makedos, I. The absorption of a shadow economy in the Greek GDP. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 9, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Canh, N.P.; Thanh, S.D. Financial development and the shadow economy: A multi-dimensional analysis. Econ. Anal. Policy 2020, 67, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Enste, D.H. Shadow economies: Size, causes, and consequences. J. Econ. Lit. 2000, 38, 77–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louail, B.; Hamida, H.B.H. Asymmetry Relationship between Economic Growth and Unemployment Rates in the Arab countries: Application of the OKUN Law during 1960–2017. Management 2021, 25, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keynes, J.M. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money; Macmillan: London, UK, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Domar, E.D. Capital expansion, rate of growth, and employment. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1946, 14, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R.M. Toward a Macroeconomics of the Medium Run. J. Econ. Perspect. 2000, 14, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgler, B.; Schneider, F. Shadow Economy, Tax Morale, Governance and Institutional Quality: A Panel Analysis; Center for Economic Studies & Ifo Institute for Economic Research: Munich, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, H. Wage flexibility and economic stability in a non-Walrasian model of economic growth. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2007, 32, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, F.; Herani, G.; Awan, N.W. An Empirical Analysis of Determinants of Tax Evasion: Evidence from South Asia. New Horiz. 2019, 13, 1992–4399. [Google Scholar]

- IMF (International Monetary Fund). World Economic Outlook; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager, T. Institutions, Transition Economies, and Economic Development; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mandroshchenko, O.; Malkova, Y.; Tkacheva, T. Influence of the shadow economy on economic growth. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2018, 16, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilat, Y.; Zinnes, C. The Shadow Economy in Transition Countries: Friend or Foe? A Policy Perspective. World Dev. 2002, 30, 1233–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Global Economics Prospects: Having Fiscal Space and Using It; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Anno, R.; Halicioglu, F. An ARDL model of unrecorded and recorded economies in Turkey. J. Econ. Stud. 2010, 37, 627–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feige, E.L. (Ed.) The Underground Economies. Tax Evasion and Information Distortion; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ikiz, A.S. Shadow Economy and Economic Growth in Turkey; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 7, pp. 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, D.K. How does the “Hidden Economy” Affect Consumers Expenditure? An Econometric Study of the UK (1960–1984); International Institute of Public Finance: Berlin, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, M. Issues in the hidden economy—A survey. Econ. Rec. 1984, 60, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.H. The Size, Origins, and Character of Mongolia’s Informal Sector during the Transition; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 1916; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- De Soto, H. Constraints on People: The Origins of Underground Economics and limits of their Growth. In Bevond the Informal Sector: Including the Excluded in Developing Countries; Institute for Contemporary Studies: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 15–47. [Google Scholar]

- Latouche, S. the Wake of the Affluent Society: An Exploration of Post-Development; Zed Books: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, O.; Khamis, M. Comparative Advantage, Segmentation and Informal Earnings: A Marginal Treatment Effects Approach. IZA Discussion Paper no. 3916. Bonn, Germany, 2008. Available online: http://ftp.iza.org/dp3916.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2019).

- Becker, K.F. The Informal Economy: Fact Finding Study; Sida: Stockholm, Sweden, 2004; Volume 76. [Google Scholar]

- Saraç, M.; Başar, R. The Effect of Informal Economy on the European Debt Crisis. Siyaset Ekon. Yönetim Araştırmaları Derg. 2014, 2, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F. (Ed.) Handbook on the Shadow Economy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham Glos, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Business Group. Available online: https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/video/saudi-arabia-economy-position-growth-coming-year (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- IMF. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2022/08/09/CF-Saudi-Arabia-to-grow-at-fastest-pace (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/thekingdom/explore/economy (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Canh, N.P.; Thanh, S.D.; Schinckus, C.; Bensemann, J.; Thanh, L.T. Global emissions: A new contribution from the shadow economy. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2019, 9, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canh, N.P.; Schinckus, C.; Thanh, S.D.; Chong, F.H.L. The determinants of the energy consumption: A shadow economy-based perspective. Energy 2021, 225, 120210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canh, P.N.; Dinh Thanh, S. Exports and the shadow economy: Non-linear effects. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2020, 29, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.P. Does economic complexity matter for the shadow economy? Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 73, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbahnasawy, N.G. Can e-government limit the scope of the informal economy? World Dev. 2021, 139, 105341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, Z.I.; Qureshi, A.; Al-Faryan, M.A.S. Financial inclusion 2021, the shadow economy and economic growth in developing economies. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2022, 62, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owolabi, A.O.; Berdiev, A.N.; Saunoris, J.W. Is the shadow economy procyclical or countercyclical over the business cycle? International evidence. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022, 84, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, T.T.H.; Nguyen, T.M.; Nguyen, T.A.N. Rule of law, economic growth and shadow economy in transition countries. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baklouti, N.; Boujelbene, Y. A simultaneous equation model of economic growth and shadow economy: Is there a difference between the developed and developing countries? Econ. Chang. Restruct. 2020, 53, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Williams, C. The Shadow Economy; The Institute of Economic Affairs Edward Elgar: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, F.; Hametner, B. The Shadow Economy in Colombia: Size and Effects on Economic Growth. Peace Econ. Peace Sci. Public Policy 2014, 20, 293–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R.M. A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Anno, R. Estimating the Shadow Economy in Italy: A Structural Equation Approach (No. 2003-7); Department of Economics and Business Economics, Aarhus University: Aarhus, Denmark, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, D.E.; Tedds, L.M. Taxes and the Canadian Underground Economy; Canadian Tax Paper (No. 106); Canadian Tax Foundation: Toronto, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mummert, A.; Schneider, F. The German shadow economy: Parted in a united Germany? Finanz. Public Financ. Anal. 2002, 58, 286–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F. Further empirical results of the size of the informal economy of 17 OECD-countries over time 2002. In Proceedings of the 54. Congress of the IIPF Cordowa, Linz, Austria, July 1998; University of Linz: Linz, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchgaessner, G. Size and development of the West German shadow economy, 1955–1980. J. Inst. Theor. Econ. 1983, 139, 197–214. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, F. Estimating the Size of the Danish Shadow Economy using the Currency Demand Approach: An Attempt. Scand. J. Econ. 1986, 88, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Kaufmann, D.; Zoido-Lobaton, P. Corruption, Public Finances and the Unofficial Economy (No. 2169); The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gulzar, A.; Junaid, N.; Haider, A. What is Hidden, in the Hidden Economy of Pakistan? Size, Causes, Issues, and Implications. Pak. Dev. Rev. 2010, 49, 665–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D. Determinants of the Informal Sector and their Effects on the Economy: The Case of Korea. Glob. Econ. Rev. 2011, 40, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, R. The Measurement of Economic Stability Over Time. 2018. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3198198 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Schneider, F.; Medina, L. Shadow Economies Around the World: New Results for 158 Countries Over 1991–2015 (No. 1710); Working Paper; Center for Economic Studies & Ifo Institute for Economic Research: Munich, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, F.; Buehn, A.; Montenegro, C.E. New Estimates for the Shadow Economies all over the World. Int. Econ. J. 2010, 24, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W. International trade, distortions, and long-run economic growth. Staff Pap. 1993, 40, 299–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovenberg, A.L.; van Ewijk, C. Progressive taxes, equity, and human capital accumulation in an endogenous growth model with overlapping generations. J. Public Econ. 1997, 64, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, T.W. Economic Growth and Capital Accumulation. Econ. Rec. 1956, 32, 334–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichengreen, B. The real exchange rate and economic growth. Soc. Econ. Stud. 2007, 56, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Din, B.H.; Habibullah, M.S.; Hamid, B.A. Re-estimation and modelling shadow economy in Malaysia: Does financial development mitigate shadow economy? Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2019, 20, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S. The Informal Economy and Islamic Finance: The Case of Organization of Islamic Cooperation Countries; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Rehman, M.Z. Macroeconomic fundamentals, institutional quality and shadow economy in OIC and non-OIC countries. J. Econ. Stud. 2022, 49, 1566–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP | 1678 | 3.99 | 4.52 | −36.70 | 38.00 |

| SDGDP | 1678 | 2.53 | 2.76 | 0.01 | 23.33 |

| SE | 1679 | 29.83 | 12.10 | 7.96 | 69.08 |

| T | 1677 | 91.49 | 56.74 | 21.12 | 442.62 |

| TAXB | 1670 | 75.19 | 12.59 | 32.00 | 99.90 |

| GE | 1665 | 15.36 | 4.95 | 2.05 | 31.57 |

| FF | 1670 | 53.28 | 18.61 | 10.00 | 90.00 |

| ER | 990 | 99.37 | 13.45 | 53.75 | 328.25 |

| ROL | 1680 | 49.47 | 29.27 | 0.47 | 100.0 |

| GCF | 1656 | 1.12 | 4.02 | 4.69 | 5.02 |

| INVF | 1670 | 54.24 | 20.73 | 0.00 | 95.00 |

| EDU | 1287 | 81.91 | 28.93 | 8.77 | 163.93 |

| PS | 1680 | 45.73 | 27.47 | 0.47 | 100.0 |

| U | 1668 | 8.094 | 5.29 | 0.10 | 37.60 |

| GDP | SDGDP | SE | T | TAXB | GE | FF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP | 1 | ||||||

| SDGDP | −0.05 | 1.00 | |||||

| SE | 0.09 | 0.07 | 1.00 | ||||

| T | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.25 | 1.00 | |||

| TAXB | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 1.00 | ||

| GE | −0.24 | −0.05 | −0.30 | 0.04 | −0.34 | 1.00 | |

| FF | −0.14 | −0.08 | −0.40 | 0.30 | −0.12 | 0.34 | 1.00 |

| ER | −0.13 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| ROL | −0.21 | −0.11 | −0.66 | 0.30 | −0.30 | 0.51 | 0.67 |

| GCF | −0.02 | −0.08 | −0.32 | −0.17 | −0.15 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| INVF | −0.19 | −0.03 | −0.43 | 0.27 | −0.20 | 0.34 | 0.73 |

| EDUS | −0.31 | −0.04 | −0.50 | 0.24 | −0.21 | 0.44 | 0.49 |

| PS | −0.16 | −0.04 | −0.54 | 0.40 | −0.24 | 0.42 | 0.54 |

| U | −0.11 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.19 | 0.03 |

| ER | ROL | GCF | INVF | EDU | PS | U | |

| ER | 1.00 | ||||||

| ROL | −0.01 | 1.00 | |||||

| GCF | 0.09 | 0.19 | 1.00 | ||||

| INVF | 0.00 | 0.71 | 0.05 | 1.00 | |||

| EDUS | 0.03 | 0.67 | 0.16 | 0.44 | 1.00 | ||

| PS | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.06 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 1.00 | |

| U | −0.19 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 1 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP/SDGDP | GMM (GDP) | GMM (SDGDP) | FE (GDP) | FE (SDGDP) | RE (GDP) | RE (SDGDP) |

| SE | −1.0567 ** | −0.3670 ** | −0.1158 * | −0.2285 ** | −0.0335 * | 0.0254 * |

| [0.447] | [0.165] | [0.063] | [0.102] | [0.019] | [0.015] | |

| L.GDP | 0.5235 *** | |||||

| [0.085] | ||||||

| L.SDGDP | 1.0539 *** | |||||

| [0.096] | ||||||

| T | 0.0534 * | 0.0138 | 0.0392 *** | 0.0397 * | 0.0077 ** | 0.0054 ** |

| [0.029] | [0.010] | [0.013] | [0.021] | [0.003] | [0.003] | |

| TAXB | −0.5450 *** | −0.1316 *** | −0.1124 *** | −0.0134 | 0.0134 | 0.0160 |

| [0.162] | [0.050] | [0.035] | [0.051] | [0.015] | [0.012] | |

| GE | −2.0999 *** | −0.1261 | −0.6038 *** | −0.6506 *** | −0.3291 *** | −0.0621 ** |

| [0.547] | [0.125] | [0.125] | [0.188] | [0.042] | [0.032] | |

| FF | 0.0342 | 0.0010 | 0.0651 *** | 0.0678 ** | 0.0049 | |

| [0.123] | [0.034] | [0.025] | [0.026] | [0.011] | ||

| ER | −0.2505 * | −0.0228 | −0.0835 *** | −0.0642 *** | 0.0270 *** | |

| [0.149] | [0.037] | [0.029] | [0.013] | [0.008] | ||

| ROL | −0.5609 ** | −0.2222 ** | ||||

| [0.231] | [0.085] | |||||

| GCF | −0.0000 *** | |||||

| [0.000] | ||||||

| INVF | 0.0073 | |||||

| [0.007] | ||||||

| EDU | −0.0262 | |||||

| [0.023] | ||||||

| PS | 0.0689 ** | −0.0138 | ||||

| [0.031] | [0.009] | |||||

| U | −0.0269 | |||||

| [0.028] | ||||||

| Constant | 157.0361 *** | 35.7475 ** | 20.2296 *** | 18.3031 ** | 14.7519 *** | −1.6533 |

| [43.209] | [13.901] | [3.858] | [7.025] | [2.125] | [1.531] | |

| Observation | 895 | 894 | 1274 | 973 | 973 | 960 |

| R2 | 0.113 | 0.178 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.108 | 0.172 | ||||

| Instruments | 21.0000 | 45.0000 | ||||

| Groups | 83 | 83 | ||||

| AR (1) | 0.0000 | 0.000 | ||||

| AR (2) | 0.1310 | 0.0061 | ||||

| Sargan | 0.1346 | 0.2625 | ||||

| F-Stats | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Dep (SDGDP) | Coefficient | Std. err. | t | p > t | [95% conf.] | [Interval] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | −1.8071 | 0.0998 | −18.1100 | 0.0350 | −3.0750 | −0.5393 |

| BD | 0.2743 | 0.0207 | 13.2300 | 0.0480 | 0.0108 | 0.5378 |

| LF | −5.6826 | 0.3376 | −16.8300 | 0.0380 | −9.9721 | −1.3932 |

| ECOF | −0.8809 | 0.0826 | −10.6600 | 0.0600 | −1.9307 | 0.1688 |

| GI | 0.6781 | 0.0662 | 10.2400 | 0.0620 | −0.1632 | 1.5195 |

| TAXB | −9.2481 | 1.4102 | −6.5600 | 0.0960 | −27.1664 | 8.6702 |

| GS | 0.1826 | 0.0196 | 9.3200 | 0.0680 | −0.0664 | 0.4316 |

| VA | −1.4542 | 0.1303 | −11.1600 | 0.0570 | −3.1094 | 0.2010 |

| COC | −0.0798 | 0.0265 | −3.0100 | 0.2040 | −0.4169 | 0.2572 |

| GEFF | 0.4108 | 0.0561 | 7.3300 | 0.0860 | −0.3015 | 1.1231 |

| Constant | 1246.67 | 150.36 | 8.29 | 0.08 | −663.84 | 3157.18 |

| F(10, 1) | 163.38 | |||||

| Prob > F | 0.0608 | |||||

| R-squared | 0.9994 | |||||

| Adj R-squared | 0.9933 | |||||

| Root MSE | 0.13416 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rehman, M.Z.; Khan, S.; Ali, M.; Rehman, F.U.; Alonazi, W.B.; Aljuaid, M. Advance Dynamic Panel Second-Generation Two-Step System Generalized Method of Movement Modeling: Applications in Economic Stability-Shadow Economy Nexus with a Special Case of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Mathematics 2023, 11, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11010085

Rehman MZ, Khan S, Ali M, Rehman FU, Alonazi WB, Aljuaid M. Advance Dynamic Panel Second-Generation Two-Step System Generalized Method of Movement Modeling: Applications in Economic Stability-Shadow Economy Nexus with a Special Case of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Mathematics. 2023; 11(1):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11010085

Chicago/Turabian StyleRehman, Mohd Ziaur, Shabeer Khan, Mohsin Ali, Faheem Ur Rehman, Wadi B. Alonazi, and Mohammed Aljuaid. 2023. "Advance Dynamic Panel Second-Generation Two-Step System Generalized Method of Movement Modeling: Applications in Economic Stability-Shadow Economy Nexus with a Special Case of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia" Mathematics 11, no. 1: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11010085

APA StyleRehman, M. Z., Khan, S., Ali, M., Rehman, F. U., Alonazi, W. B., & Aljuaid, M. (2023). Advance Dynamic Panel Second-Generation Two-Step System Generalized Method of Movement Modeling: Applications in Economic Stability-Shadow Economy Nexus with a Special Case of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Mathematics, 11(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11010085