Capital Structure Theory: Past, Present, Future

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Basic Theories of Capital Structure

2.1. A Historical Point of View

2.2. The Empirical (Traditional) Approach

2.3. The Modigliani–Miller Theory

2.3.1. The Modigliani–Miller Theory with Taxes

2.3.2. The Modigliani–Miller Theory with Taxes

2.4. Modifications of Modigliani–Miller Theory

2.4.1. Hamada Model

2.4.2. The Cost of Capital under Risky Debt

2.4.3. The Account of Corporate and Individual Taxes (Miller Model)

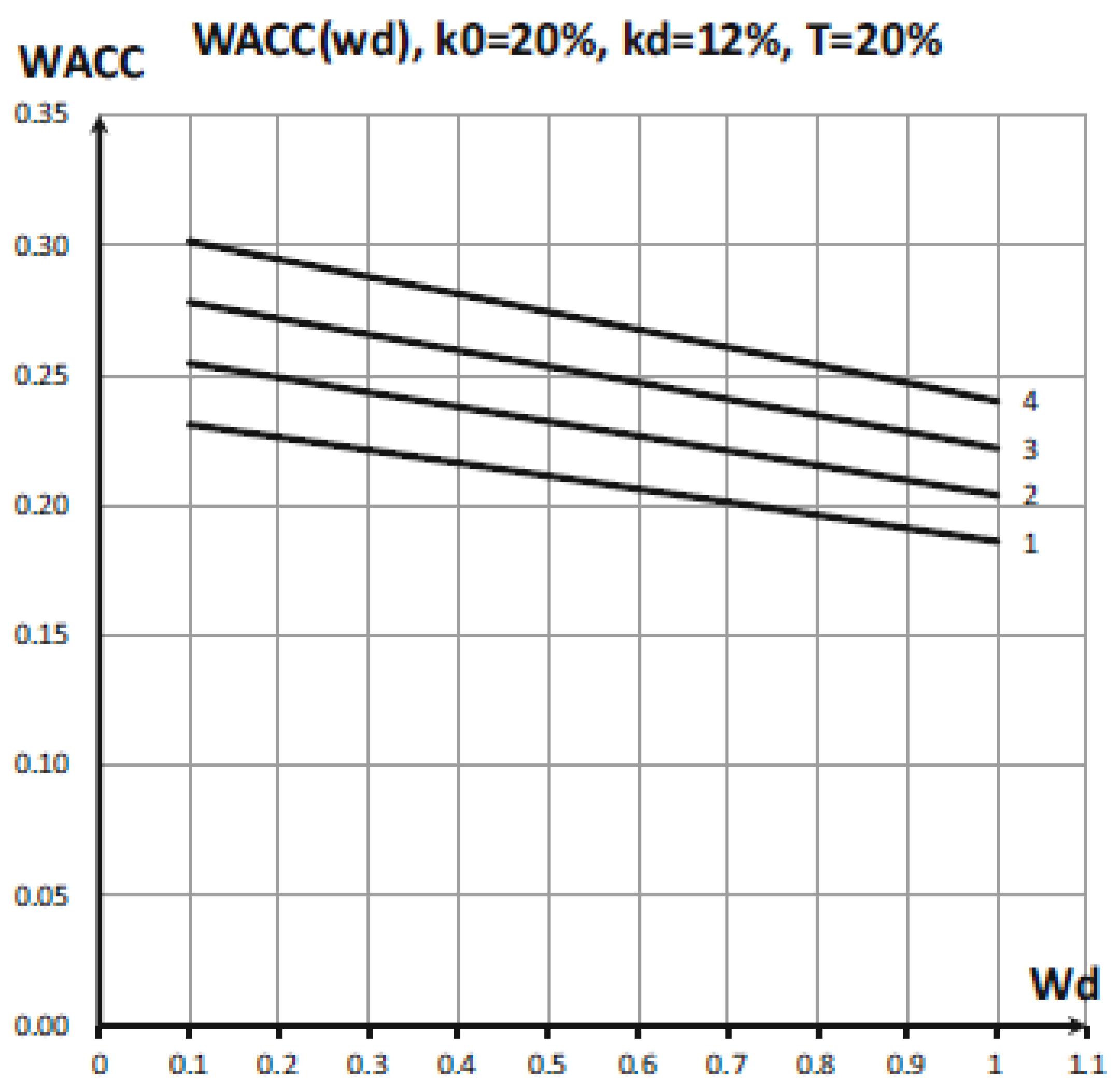

2.4.4. Alternative Expression for WACC

2.4.5. The Miles–Ezzell Model Versus the Modigliani–Miller Theory

3. Trade–Off Theory

3.1. Static Theory

3.2. Dynamic Theory

3.3. Proof of the Bankruptcy of the Trade-Off Theory

4. Accounting for Transaction Costs

5. Accounting for Asymmetries of Information

6. Signaling Theory

7. Pecking Order Theory

8. Behavioral Theories

8.1. Manager Investment Autonomy

8.2. The equity Market Timing Theory

8.3. Information Cascades

9. Theories of Conflict of Interests

9.1. Theory of Agency Costs

9.2. Theory of Corporate Control and Costs Monitoring

9.3. Theory of Stakeholders

10. BFO Theory

Brusov–Filatova–Orekhova Theorem

Case of Absence of Corporate Taxes

11. BFO Theory and Modigliani–Miller Theory under Inflation

12. BFO Theory for the Companies Ceased to Exist at the Time Moment n (BFO–2 Theory)

13. The Modigliani–Miller Theory with Advance Payments of Tax on Profit

14. The Modigliani–Miller Theory with Arbitrary Frequency of Payment of Tax on Profit

15. Generalization of the Modigliani–Miller Theory for the Case of Variable Profit

16. The Generalization of the Brusov–Filatova–Orekhova Theory for the Case of Payments of Tax on Profit with Arbitrary Frequency

17. Benefits of Advance Payments of Tax on Profit: Consideration within the Brusov–Filatova–Orekhova (BFO) Theory

18. Influence of Method and Frequency of Profit Tax Payments on Company Financial Indicators

19. The Brusov–Filatova–Orekhova (BFO) Theory with Variable Income

20. Qualitatively New Effects in the Theory of Capital Structure

- Golden and silver ages of the company

- Anomalous dependence of the cost of equity on the leverage level

20.1. Golden and Silver Ages of the Company

20.2. Silver Age of the Company

20.3. Anomalous Dependence of the Company’s Equity Value on Leverage

21. A Stochastic Extension of the Modigliani–Miller Theory

22. Conclusions

- generalization of the BFO theory and the MM theory to the case of a company’s variable-in-time income;

- generalization of the BFO theory to the stochastic case and to the case of a company’s variable-in-time income;

- further generalization of the BFO theory and MM theory on the conditions for the practical functioning of the company;

- study the dependence of the effects of the “golden and silver age of the company” on the growth rate of income in the case of a company’s variable income, on the frequency of income tax payment, on the advance payment of income tax, and on a combination of these conditions;

- develop a methodology for determining the financial parameters of a company in the event of a drop in income, in the event of an increase in the company’s income, as well as in the case of alternating growth and falling income.

- -

- analysts can evaluate the company’s financial indicators for companies of arbitrary age;

- -

- allows for taking into account the conditions of the company’s real functioning;

- -

- allows to take into account the anomalous effects discovered in the BFO theory (such as “Golden age”, “abnormal dependence of equity cost with leverage”, etc.), which allow for making nonstandard effective management decisions;

- -

- allows the regulator to improve tax policy;

- -

- allows for the correct determination of the discount rate, which is extremely important in business valuation;

- -

- allows us to correctly determine the effectiveness of investments through the correct determination of the discount rate;

- -

- allows to correctly issue ratings of nonfinancial issuers, financial issuers, and investment projects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Modigliani, F.; Miller, M.H. The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. Am. Econ. Rev. 1958, 48, 261–296. [Google Scholar]

- Modigliani, F.; Miller, M.H. Corporate income taxes and the cost of capital: A correction. Am. Econ. Rev. 1963, 53, 433–443. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.H. Debt and taxes. J. Financ. 1977, 32, 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.H.; Modigliani, F. Dividend policy, growth and the valuation of shares. J. Bus. 1961, 34, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.H.; Modigliani, F. Some estimates of the cost of capital to the electric utility industry, 1954–1957. Am. Econ. Rev. 1966, 56, 333–391. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, V.; Myers, S.C.; Rajan, R. The internal governance of firms. J. Financ. 2011, 66, 689–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arrow, K.J. The role of securities in the optimal allocation of risk-bearing. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1964, 31, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asquith, P.; Mullins, D.W. Equity issues and offering dilution. J. Financ. Econ. 1986, 15, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W.; Panzar, J.G.; Willig, R.D. Contestable Markets and the Theory of Industry Structure; Harcourt College Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Black, F. Noise. J. Financ. 1986, 41, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, D.M. The difference between Modigliani–Miller and Miles–Ezzell and its consequences for the valuation of annuities. Cogent. Econ. Financ. 2021, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, J.; DeMarzo, P. Corporate Finance; Pearson–Addison Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brealey, R.A.; Myers, S.C. Principles of Corporate Finance, 1st ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Brealey, R.A.; Myers, S.C.; Allen, F. Principles of Corporate Finance, 11th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, S. Project valuation with mean-reacting cash flows. J. Financ. 1978, 33, 1317–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatova, Т.; Orehova, N.; Brusova, А. Weighted average cost of capital in the theory of Modigliani–Miller, modified for a finite life–time company. Bull FU 2008, 48, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Brusov, P.; Filatova, T.; Orehova, N.; Eskindarov, M. Modern Corporate Finance, Investments, Taxation and Ratings, 2nd ed.; Springer Nature Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–571. [Google Scholar]

- Brusov, P.; Filatova, T.; Eskindarov, M.; Orehova, N. Hidden global causes of the global financial crisis. J. Rev. Glob. Econ. 2012, 1, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusov, P.; Filatova, P.; Orekhova, N. Absence of an optimal capital structure in the famous tradeoff theory! J. Rev. Glob. Econ. 2013, 2, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brusov, P.; Filatova, T.; Orehova, N. A qualitatively new effect in corporative finance: Abnormal dependence of cost of equity of company on leverage. J. Rev. Glob. Econ. 2013, 2, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusov, P.; Filatova, P.; Orekhova, N. Mechanism of formation of the company optimal capital structure. different from suggested by trade off theory. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2014, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusov, P.; Filatova, T.; Orehova, N. Inflation in Brusov–Filatova–Orekhova theory and in its perpetuity limit–Modigliani–Miller theory. J. Rev. Glob. Econ. 2014, 3, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brusova, A. А comparison of the three methods of estimation of weighted average cost of capital and equity cost of company. Financ. Anal. Prob. Sol. 2011, 34, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Derrig, R. Theoretical considerations of the effect of federal income taxes on investment income in property-liability ratemaking. J. Risk Insur. 1994, 61, 691–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D.A.; He, Z. A theory of debt maturity: The long and short of debt overhang. J. Financ. 2014, 69, 719–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, G. Debt Capacity: A Study of Corporate Debt Policy and the Determination of Debt Capacity; Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University: Boston, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Erel, I.; Myers, S.C.; Read, J.A., Jr. A theory of risk capital. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 118, 620–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairley, W.B. Investment income and profit margins in property-liability insurance. Bell J. Econ. 1979, 10, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F. Risk adjusted discount rates and capital budgeting under uncertainty. J. Financ. Econ. 1977, 5, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F. Discounting under uncertainty. J. Bus. 1996, 69, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K. Financing decisions: Who issues stock? J. Financ. Econ. 2005, 76, 549–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, A.; Gillet, R.; Szafarz, A. A General Formula for the WACC. Int. J. Bus. 2006, 11, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, P. A General Formula for the WACC: A Comment. Int. J. Bus. 2006, 11, 219. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, F.M.; McGowan, J.J. On the misuse of accounting rates of return to infer monopoly profits. Am. Econ. Rev. 1983, 73, 82–97. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, M.Z.; Goyal, V.K. Testing the pecking order theory of capital structure. J. Financ. Econ. 2003, 67, 217–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gordon, M.J.; Shapiro, E. Capital equipment analysis: The required rate of profit. Manag. Sci. 1956, 3, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graham, J.R.; Leary, M.T. A review of empirical capital structure research and directions for the future. Annu. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2011, 3, 309–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, R. Portfolio Analysis, Market Equilibrium, and Corporate Finance. J. Financ. 1969, 24, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.; Pringle, J. Risk–Adjusted Discount Rates—Extension form the Average–Risk Case. J. Financ. Res. 1985, 8, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J.; Myers, S.C. Regulating, U.S. railroads: The effects of sunk costs and asymmetric risk. J. Regul. Econ. 2002, 22, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.; Howe, C.; Myers, S.C. R&D accounting the tradeoff between relevance objectivity: A pharmaceutical industry simulation. J. Account. Res. 2002, 40, 677–710. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshleifer, J. Investment decision under uncertainty: Choice-theoretic approaches. Q. J. Econ. 1965, 79, 509–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshleifer, J. Investment decision under certainty: Applications of the state-preference approach. Q. J. Econ. 1966, 80, 252–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C. Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance and takeovers. Am. Econ. Rev. 1986, 76, 323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.; Myers, S.C. R2 around the world: New theory and new tests. J. Financ. Econ. 2006, 79, 257–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaplan, S.; Ruback, R. The valuation of cash flow forecasts: An empirical analysis. J. Financ. 1995, 50, 1059–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.C. Finance, Theoretical and Applied. Annu. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2015, 7, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keynes, J.M. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, A.L.; Tye, W.B.; Myers, S.C. Regulatory Risk: Economic Principles and Applications to Natural Gas Pipelines and Other Industries; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht, B.; Myers, S.C. A theory of takeovers and disinvestment. J. Financ. 2007, 62, 809–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, B.; Myers, S.C. Debt and managerial rents in a real-options model of the firm. J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 89, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, B.; Myers, S.C. A Lintner model of dividends and managerial rents. J. Financ. 2012, 67, 1761–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, B.; Myers, S.C. The Dynamics of Investment, Payout and Debt; Working Paper; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon, M.L.; Roberts, M.R.; Zender, J. Back to the beginning: Persistence and the cross-section of corporate capital structure. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 1575–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, M.L.; Zender, J. Debt capacity and tests of capital structure theories. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2010, 45, 1161–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lintner, J. Distribution of incomes of corporations between dividends, retained earnings and taxes. Am. Econ. Rev. 1956, 46, 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lintner, J. Optimal dividends and corporate growth under uncertainty. Q. J. Econ. 1965, 77, 59–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majd, S.; Myers, S.C. Tax asymmetries and corporate income tax reform. In The Effects of Taxation on Capital Accumulation; Feldstein, M., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1987; pp. 343–373. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, M. DeMarzo an Extension of the Modigliani-Miller Theorem to Stochastic Economies with Incomplete Markets and Fully Interdependent Securities. J. Econ. Theory 1988, 45, 353–369. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.C.; Perold, A.F. Theory of risk capital in financial firms. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 1993, 6, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J.; Ezzell, R. The weighted average cost of capital, perfect capital markets and project life: A clarification. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 1980, 15, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morck, R.; Yeung, B.Y.; Yu, W. The information content on stock markets: Why do emerging markets have synchronous stock price movements? J. Financ. Econ. 2000, 58, 215–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mullins, D.W., Jr. Communications Satellite Corp. Case Study 276195; Harvard Bus. Sch.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.C. Effects of Uncertainty on the Valuation of Securities and the Financial Decisions of the Firm. Ph.D. Thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.C. A time-state-preference model of security valuation. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 1968, 3, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.C. Procedures for capital budgeting under uncertainty. Ind. Manag. Rev. 1968, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.C. Application of finance theory to public utility rates cases. Bell J. Econ. 1972, 3, 58–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.C. A simple model of firm behavior under regulation and uncertainty. Bell J. Econ. 1973, 4, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, S.C. On public utility regulation under uncertainty. In Risk and Regulated Firms; Howard, R.H., Ed.; Mich. State Univ. Div. Res. Grad. Sch. Bus.: East Lansing, MI, USA, 1973; pp. 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.C. Interactions of corporate financing and investment decisions: Implications for capital budgeting. J. Financ. 1974, 29, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.C. Capital structure. J. Econ. Perspect. 2001, 15, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, S.C. Finance theory and financial strategy. Interfaces 1984, 14, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, S.C. The capital structure puzzle. J. Financ. 1984, 39, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, S.C. Fuzzy efficiency. Inst. Investig. 1988, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.C. Still searching for optimal capital structure. In Are the Distinctions between Debt and Equity Disappearing? Kopke, R.W., Rosengren, E.S., Eds.; Federal Reserve Bank: Boston, MA, USA, 1989; pp. 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.C. Financial architecture. Eur. Financ. Manag. 1999, 5, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.C. Outside equity. J. Financ. 2000, 55, 1005–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.C.; Cohn, R. A discounted cash flow approach to property-liability insurance rate regulation. In Fair Rate of Return in Property Liability Insurance; Cummings, J.D., Harrington, S., Eds.; Kluwer-Nijhoff: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1987; pp. 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.C.; Dill, D.A.; Bautista, A.J. Valuation of financial lease contracts. J. Financ. 1976, 31, 799–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.C.; Howe, C. A Life Cycle Model of Pharmaceutical R&D; Working Paper; Progr. Pharm. Ind.; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.C.; Kolbe, A.L.; Tye, W.B. Regulation and capital formation in the oil pipeline industry. Transp. J. 1984, 23, 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.C.; Kolbe, A.L.; Tye, W.B. Inflation and rate of return regulation. Res. Transp. Econ. 1985, 2, 83–119. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.C.; Majd, S. Abandonment value and project life. In Advances in Futures and Options Research; Fabozzi, F., Ed.; JAI: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1990; Volume 4, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.C.; Majluf, N.S. Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. J. Financ. Econ. 1984, 13, 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, S.C.; Pogue, G.A. A programming approach to corporate financial management. J. Financ. 1974, 29, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.C.; Rajan, R. The paradox of liquidity. Q. J. Econ. 1998, 113, 733–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, S.C.; Read, J.A., Jr. Capital allocation for insurance companies. J. Risk Insur. 2001, 68, 545–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.C.; Read, J.A., Jr. Real Options, Taxes and Leverage; Working Paper; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.C.; Shyam-Sunder, L. Measuring pharmaceutical industry risk and the cost of capital. In Competitive Strategies in the Pharmaceutical Industry; Helms, R.B., Ed.; American Enterpise Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; pp. 208–237. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.C.; Turnbull, S.M. Capital budgeting and the capital asset pricing model: Good news and bad news. J. Financ. 1977, 32, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichek, A.A.; Myers, S.C. Optimal Financing Decisions; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Robichek, A.A.; Myers, S.C. Conceptual problems in the use of risk-adjusted discount rates. J. Financ. 1966, 21, 727–730. [Google Scholar]

- Robichek, A.A.; Myers, S.C. Problems in the theory of optimal capital structure. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 1966, 1, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichek, A.A.; Myers, S.C. Valuation of the firm: Effects of uncertainty in a market context. J. Financ. 1966, 21, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, J.; Pearl, J. Investment Banking, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, S.; Derzko, N.A.; Lehoczky, J.P. A Stochastic Extension of the Miller-Modigliani Framework. Math. Financ. 1991, 1, 57–76. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1082940 (accessed on 21 December 2021). [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, E. The theory of the capital structure of the firm. J. Financ. 1959, 14, 18–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, W.F. Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. J. Financ. 1965, 19, 425–442. [Google Scholar]

- Shleifer, A.; Summers, L.H. Breach of trust in hostile takeovers. In Corporate Takeovers: Causes and Consequences; Auerbach, A.J., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1988; pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Shyam-Sunder, L.; Myers, S.C. Testing static tradeoff against pecking order models of capital structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1999, 51, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, D.J. The evolving relation between earnings, dividends and stock repurchases. J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 87, 582–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, E.; Laya, J. Measurement of company profitability: Some systematic errors in the accounting rate of return. In Financial Research and Management Decisions; Robichek, A.A., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1967; pp. 152–183. [Google Scholar]

- Van Horne, J. Capital budgeting decisions involving combinations of risky assets. Manag. Sci. 1966, 19, B84–B92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.B. The Theory of Investment Value; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Brusov, P.N.; Filatova, T.V.; Orekhova, N.P.; Kulik, V.L.; Chang, S.I.; Lin, Y.C.G. Modification of the Modigliani–Miller Theory for the Case of Advance Payments of Tax on Profit. J. Rev. Glob. Econ. 2020, 9, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusov, P.; Filatova, T.; Orekhova, N.; Kulik, V.; Chang, S.-I.; Lin, Y. Application of the Modigliani–Miller Theory, Modified for the Case of Advance Payments of Tax on Profit, in Rating Methodologies. J. Rev. Glob. Econ. 2020, 9, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusov, P.; Filatova, T.; Chang, S.-I.; Lin, G. Innovative investment models with frequent payments of tax on income and of interest on debt. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusov, P.; Filatova, T.; Orekhova, N.; Kulik, V.; Chang, S.-I.; Lin, G. Generalization of the Modigliani–Miller theory for the case of variable profit. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusov, P.; Filatova, T. The Modigliani–Miller theory with arbitrary frequency of payment of tax on profit. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusov, P.; Filatova, T.; Orekhova, N.; Kulik, V.; Chang, S.-I.; Lin, G. The Generalization of the Brusov–Filatova–Orekhova Theory for the Case of Payments of Tax on Profit with Arbitrary Frequency. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusov, P.; Filatova, T.; Kulik, V. Benefits of Advance Payments of Tax on Profit: Consideration within the Brusov–Filatova–Orekhova (BFO) Theory. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, B.; Tatiana, F. Influence of Method and Frequency of Profit Tax Payments on Company Financial Indicators. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, B.; Tatiana, F. Generalization of the Brusov–Filatova–Orekhova Theory for the Case of Variable Income. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatova, T.; Brusov, P.; Orekhova, N. Impact of Advance Payments of Tax on Profit on Effectiveness of Investments. Mathematics 2022, 10, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. A Re–examination of the Modigliani–Miller Theorem. Am. Econ. Rev. 1969, 59, 784–793. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein, M. A Mean–Variance Synthesis of Corporate Financial Theory. J. Financ. 1973, 28, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia, С. Coherence of the Modern Theories of Finance. Financ. Rev. 1981, 16, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, I.; Nyborg, K.G. Consistent valuation of project finance and LBO’s using the flow-to-equity method. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2018, 24, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.; Schwartz, E. Corporate Income Taxes, Valuation, and the Problem of Optimal Capital Structure. J. Bus. 1978, 51, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leland, H. Corporate Debt Value, Bond Covenants, and Optimal Capital Structure. J. Financ. 1994, 49, 1213–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.; Schwartz, E. Optimal Financial Policy and Firm Valuation. J. Financ. 1984, 39, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, A.; Marcus, A.; McDonald, R. How Big is the Tax Advantage to Debt? J. Financ. 1984, 39, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theory | Main Thesis | |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional theory | Before appearance of the first quantitative theory of capital structures (Modigliani–Miller theory) in 1958 [1,2,3,4,5] empirical theory existed. Weighted average cost of capital, WACC, and company value, V, depends on capital structures of company. Within the based on existing practical experience traditional approach the competition between the advantages of debt financing at a low leverage level and its disadvantages at a high leverage level forms the optimal capital structure, defined as the leverage level, at which WACC is minimal and company value, V, is maximum. | |

| Modigliani–Miller theory (ММ) | Without taxes | Under many constraints, Modigliani and Miller concluded that the cost of raising capital and capitalization of a company do not depend on the company’s capital structure at all. |

| With taxes | Under corporate taxation, the weighted average cost of capital WACC decreases with the level of leverage, the cost of equity ke increases linearly with the level of leverage, and the value of the company V increases continuously with the level of leverage. | |

| Brusov–Filatova–Orekhova theory (BFO–1) | For arbitrary age Without inflation | In 2008 Brusov–Filatova–Orekhova (BFO) theory [16] has replaced the famous Modigliani and Miller theory [1,2,3,4,5]. The authors have moved from the assumption of Modigliani–Miller concerning the perpetuity (infinite time of life) of companies and elaborated the quantitative theory of valuation of main indicators of financial activities of arbitrary age companies. Results of modern BFO theory turn out to be quite different from that of Modigliani–Miller theory. It shows that later, via its perpetuity, underestimates the valuation of cost of raising capital the company and substantially overestimates the valuation of the company value. Such an incorrect valuation of main financial parameters of companies has led to an underestimation of risks involved, and impossibility, or serious difficulties in adequate managerial decision–making, which was one of the implicit reasons of 2008 global financial crisis. In the BFO theory, in investments at certain values of return–on–investment, there is an optimum investment structure. As well a new mechanism of formation of the company optimal capital structure, different from suggested by trade–off theory has been developed. |

| For arbitrary age With inflation | Inflation has a twofold effect on costs of raising capital: (1) increases the equity cost and the weighted average cost of capital, (2) changes their dependence on leverage, increasing, in particular, the rate of growth of the cost of equity with leverage. The company value decreases under accounting of inflation. | |

| For arbitrary age With increased financial distress costs and risk of bankruptcy | In Brusov–Filatova–Orekhova (BFO) theory, with increased financial costs and bankruptcy risk, there is no optimal capital structure, which means that the trade-off theory does NOT work. | |

| Brusov–Filatova–Orekhova theory (BFO–2) | For arbitrary lifetime | In the Modigliani-Miller theory (in the limit of eternity), the lifetime of a company and the age of a company mean the same thing: they are both infinite. When moving to a company with a finite age, the terms “company lifetime” and “company age” become different, and they should be distinguished when generalizing the Modigliani–Miller theory to a finite n. Thus Brusov et al. have developed two kinds of finite n – theories: BFO–1 and BFO–2. BFO–1 theory is related to companies with arbitrary age and BFO–2 theory is related to companies with arbitrary life–time companies. By other words, BFO–1 is applicable for most interesting case of companies that reached the age of n–years and continue to exist on the market, and allows to analyze the financial condition of the operating companies. BFO–2 theory allows examine the financial status of the companies which ceased to exist, i.e., of those for which n means not age, but a life–time, i.e., the time of existence. In real economy there are a lot of schemes of termination of activities of the company: bankruptcy, merger, acquisition, etc. One of those schemes, when the value of the debt capital D becomes zero at the time of termination of activity of company n, is considered in Brusov et al. [17], where as well where the results of BFO-1 and BFO-2 are also compared. |

| Brusov–Filatova–Orekhova theory (BFO–3) | For rating needs | A new approach to rating methodology (for non–financial issuers and for long–term project rating), within both BFO and MM theories has been developed be Brusov et al. [17,106]. The key factors of a new approach are: (1) The adequate use of discounting of financial flows virtually not used in existing rating methodologies, (2) The incorporation of rating parameters (financial "ratios") into these theories. This on the one hand allows use the powerful tools of these theories in the rating, and on the other hand it ensures the correct discount rates when discounting of financial flows. The interplay between rating ratios and leverage level which is quite important in rating. This creates a new base for rating methodologies, which allows to issue more correct ratings of issuers, makes the rating methodologies more understandable and transparent. |

| Trade–off theory | Static | During decades one of the main theory of capital structure was the trade–off theory. There are two modifications of trade–off theory: the static and dynamic. Static The static trade–off theory accounts the income tax and cost of bankruptcy. Within this theory the optimal capital structure is formed by the balancing act between the benefits of debt financing at low leverage level (from the tax shield from interest deduction) and the disadvantage of debt financing at high leverage level (from the increased financial distress and expected bankruptcy costs). The tax shield benefit is equal to the product of corporate income tax rate and the market value of debt and the expected bankruptcy costs are equal to the product of probability of bankruptcy and the estimated bankruptcy costs. The static version of the trade–off theory does not take into account the costs of the adapting of the capital structure to the optimal one, economic behavior of managers, owners, and other participants of economical process, as well as a number of other factors. |

| As it has been shown in BFO theory, the optimal capital structure is absent in trade–off theory | ||

| Dynamic | The dynamic version of trade-off theory suggests that the costs of adjusting the capital structure are high, and therefore companies will only change their capital structure if the benefits outweigh the costs. Therefore, there is an optimal range that varies on the outside of each lever but remains the same on the inside. Companies try to adjust their leverage when it reaches the edge of the optimal range. Depending on the type of adaptation costs, companies reach the target ratio faster or slower. Proportional changes involve a small adjustment, while fixed changes imply significant costs. In the dynamic version of the trade–off theory, company capital structure decision in current period depends on the waiting company income in the next period. As it has been shown within BFO theory [19], under increased financial distress costs and bankruptcy risk, the optimal capital structure is absent. This means that the trade-off theory does NOT work in either the static or dynamic version. | |

| In BFO theory, with increased financial distress costs and risk of bankruptcy, the optimal capital structure is absent, which means that trade–off theory does NOT work: in static version as well as in dynamic one | ||

| Accounting of transaction cost | If the cost of changing the capital structure to its optimal value is high, the company may decide not to change the capital structure and maintain the current capital structure. The company may decide that it is more cost effective not to change the capital structure, even if it is not optimal, for a certain period of time. Because of this, the actual and target capital structure may differ. | |

| Accounting of asymmetry of information | In real financial markets, information is asymmetric (company managers have more reliable information than investors and creditors), and the rationality of economic entities is limited. | |

| Signaling theory | Information asymmetry can be reduced based on certain signals for lenders and investors related to the behavior of managers in the capital market. It should take into account the previous company development and the current and projected profitability of the activity. | |

| Pecking order theory | The pecking order theory describes a preferred sequence of funding types for raising capital. That is, companies first use financing from retained earnings (internal equity), the second source is debt, and the last source is the issuance of new shares of common stock (external equity). Empirical data on the leverage level of non-financial companies, combined with the decision-making process of top management and the board of directors, indicate a greater commitment to pecking order theory. Note that this theory contradicts both MM and BFO theory, which underline the quite importance of debt financing. | |

| Theories of conflict of interests | Theory of agency costs | The company management may make decisions that are contrary to the interests of shareholders or creditors, respectively; expenses are necessary to control its actions. For solving the agency problem the correct choice of the compensation package (the agent’s share in the property, bonus, stock options) is needed, which allows you to link the managers profit with the dynamics of equity capital and ensure the motivation of managers for preservation and growth of equity capital. |

| Theory of corporate control and costs monitoring | In the presence of information asymmetry, creditors providing capital are interested in the possibility of self-control of the effectiveness of its use and return. Monitoring costs are usually passed on to company owners by being included in the loan rate. The level of monitoring costs depends on the scale of the business; therefore, with the increase in the scale of the business, the company weighted average capital cost increases, and the company market value decreases. | |

| Theory of stakeholders | Stakeholder theory is a theory that defines and models the groups that are the stakeholders of a company. The diversity and intersection of interests of stakeholders, their different assessment of acceptable risk give rise to conditions for a conflict of their interests, that is, they make adjustments to the process of the capital structure optimizing. | |

| Behavioral theories | Manager investment autonomy | Company managers implement those decisions that, from their point of view, will be positively perceived by investors and, accordingly, will positively affect the market value of companies: when the market value of the company’s shares and the degree of consensus between the expectations of managers and investors is high, the company conducts an additional share issue, and in the opposite situation uses debt instruments. Thus, the company capital structure is more influenced by investors, whose expectations are taken into account by company managers. |

| The equity market timing theory | The level of leverage is determined by market dynamics. Equity market timing theory means that a company should issue shares at a high price and repurchase them at a low price. The idea is to take advantage of the temporary fluctuations in the value of equity relative to the value of other forms of capital. | |

| Information cascades | To save costs and avoid mistakes, the company’s capital structure can be formed not on the basis of calculations of the optimal capital structure (this is a non-trivial task and its correct solution could be found within the framework of the BFO theory) or depending on the available sources of financing of the company, but borrowed from other companies, having successful, proven managers (heads of companies), as well as using (following the majority) the most popular methods of managing the capital structure, or even simply by copying of the capital structure of successful companies in a similar industry. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brusov, P.; Filatova, T. Capital Structure Theory: Past, Present, Future. Mathematics 2023, 11, 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11030616

Brusov P, Filatova T. Capital Structure Theory: Past, Present, Future. Mathematics. 2023; 11(3):616. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11030616

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrusov, Peter, and Tatiana Filatova. 2023. "Capital Structure Theory: Past, Present, Future" Mathematics 11, no. 3: 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11030616