Mathematical Modeling of High-Energy Shaker Mill Process with Lumped Parameter Approach for One-Dimensional Oscillatory Ball Motion with Collisional Heat Generation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Description

3. Mathematical Modeling

3.1. Particle Contact Model

3.2. Collision-Induced Heating Model

3.3. Heat Transfer Model

3.4. Internal Energy Time Evolution

3.5. Hamilton’s Equations

4. Numerical Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsuzuki, T.; McCormick, P.G. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 5143–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delogu, F.; Deidda, C.; Mulas, G.; Schiffini, L.; Cocco, G. A Quantitative Approach to Mechanochemical Processes. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 5121–5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varin, R.A.; Li, S.; Wronski, Z.; Morozova, O.; Khomenko, T. The Effect of Sequential and Continuous High-Energy Impact Mode on the Mechano-Chemical Synthesis of Nanostructured Complex Hydride Mg2FeH6. J. Alloys Compd. 2005, 390, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatchard, T.D.; Genkin, A.; Obrovac, M.N. Rapid Mechanochemical Synthesis of Amorphous Alloys. AIP Adv. 2017, 7, 045201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanarayana, C. Mechanical Alloying and Milling. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2001, 46, 1–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.F.; Li, F.; Chen, Z.W.; Coppex, C.; Kim, S.J.; Noh, H.J.; Fu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Singh, C.V.; Siahrostami, S.; et al. Mechanochemistry for Ammonia Synthesis under Mild Conditions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.; Qiu, D.; Chen, Y.; Cui, X. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Ammonia Employing H2O as the Proton Source Under Room Temperature and Atmospheric Pressure. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Paskevicius, M.; Humphries, T.D.; Buckley, C.E. Simultaneous Preparation of Sodium Borohydride and Ammonia Gas by Ball Milling. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 25347–25356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerstenau, D.W.; Abouzeid, A.Z.M. The Energy Efficiency of Ball Milling in Comminution. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2002, 67, 161–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, A.I.; Kurlov, A.S. Production of Nanocrystalline Powders by High-Energy Ball Milling: Model and Experiment. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 265302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V.K.; Sharma, S. Analysis of Ball Mill Grinding Operation Using Mill Power Specific Kinetic Parameters. Adv. Powder Technol. 2014, 25, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanovich, A.A.; Romanovich, L.G.; Chekhovskoy, E.I. Determination of Rational Parameters for Process of Grinding Materials Pre-Crushed by Pressure in Ball Mill. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 327, 042091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyryanov, V.V. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Complex Oxides. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2008, 77, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapshin, O.V.; Boldyreva, E.V.; Boldyrev, V.V. Role of Mixing and Milling in Mechanochemical Synthesis (Review). Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 66, 433–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriawan, H.; Andersen, S.Z.; Zhang, X.; Comer, B.M.; Barrio, J.; Chen, P.; Medford, A.J.; Stephens, I.E.L.; Chorkendorff, I.; Shao-Horn, Y. Methods for Nitrogen Activation by Reduction and Oxidation. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2021, 1, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, P.A.; Friščić, T. Methods for Monitoring Milling Reactions and Mechanistic Studies of Mechanochemistry: A Primer. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 5726–5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, L.; McHenry, J.S. Temperature of the Milling Balls in Shaker and Planetary Mills. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 5246–5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Martin Scholze, H.; Stolle, A. Temperature Progression in a Mixer Ball Mill. Int. J. Ind. Chem. 2016, 7, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, C.; Titscher, L.; Breitung-Faes, S.; Kwade, A. Dry Grinding in Planetary Ball Mills: Evaluation of a Stressing Model. Adv. Powder Technol. 2018, 29, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, C.F.; Hofer, M.; Molaiyan, P.; Michalowski, P.; Kwade, A. Characterization of Stressing Conditions in a High Energy Ball Mill by Discrete Element Simulations. Processes 2022, 10, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.C.; Jiang, T.; Kim, N.I.; Kwon, C. Effects of Ball-to-Powder Diameter Ratio and Powder Particle Shape on EDEM Simulation in a Planetary Ball Mill. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2022, 99, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S Paramanantham, S.; Brigljević, B.; Ni, A.; Nagulapati, V.M.; Han, G.F.; Baek, J.B.; Mikulčić, H.; Lim, H. Numerical Simulation of Ball Milling Reactor for Novel Ammonia Synthesis under Ambient Conditions. Energy 2023, 263, 125754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Chen, Z.; Hou, Q.; Yu, A.; Yang, R. DEM Investigation of Heat Transfer in a Drum Mixer with Lifters. Powder Technol. 2017, 314, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Doroodchi, E.; Moghtaderi, B. Heat Transfer Modelling in Discrete Element Method (DEM)-Based Simulations of Thermal Processes: Theory and Model Development. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2020, 79, 100847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, E.; Hassan Hashemabadi, S. Three-Dimensional Heat Transfer in a Particulate Bed in a Rotary Drum Studied via the Discrete Element Method. Particuology 2020, 51, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, L.; Antonyuk, S.; Heinrich, S.; Palzer, S. DEM–CFD Modeling of a Fluidized Bed Spray Granulator. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 2340–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Zhang, K. Coupling Discrete-Element Method and Computation Fluid Mechanics to Simulate Aggregates Heating in Asphalt Plants. J. Eng. Mech. 2015, 141, 04014129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Rai, K.; Tsuji, T.; Washino, K.; Tanaka, T.; Oshitani, J. Upscaled DEM-CFD Model for Vibrated Fluidized Bed Based on Particle-Scale Similarities. Adv. Powder Technol. 2020, 31, 4598–4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigmetova, A.; Masi, E.; Simonin, O.; Dufresne, Y.; Moureau, V. Three-Dimensional DEM-CFD Simulation of a Lab-Scale Fluidized Bed to Support the Development of Two-Fluid Model Approach. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2022, 156, 104189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirosawa, F.; Iwasaki, T. Dependence of the Dissipated Energy of Particles on the Sizes and Numbers of Particles and Balls in a Planetary Ball Mill. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2021, 167, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño-Salguero, J.; Jorge, J.; Menéndez-Aguado, J.M.; Álvarez-Rodriguez, B.; de Felipe, J.J. Heat Generation Model in the Ball-Milling Process of a Tantalum Ore. Miner. Metall. Process. 2017, 34, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhu, H.; Hua, J. Granular Flow Characteristics and Heat Generation Mechanisms in an Agitating Drum with Sphere Particles: Numerical Modeling and Experiments. Powder Technol. 2018, 339, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, K.J. Mathematical Modeling of Collisional Heat Generation and Convective Heat Transfer Problem for Single Spherical Body in Oscillating Boundaries. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravati, C.; Delogu, F.; Cocco, G.; Rustici, M. Hyperchaotic Qualities of the Ball Motion in a Ball Milling Device. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 1999, 9, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concas, A.; Lai, N.; Pisu, M.; Cao, G. Modelling of Comminution Processes in Spex Mixer/Mill. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2006, 61, 3746–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Parametric Evaluation of Powder Flowability Using a Freeman Rheometer through Statistical and Sensitivity Analysis: A Discrete Element Method (DEM) Study. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2017, 97, 161–174. [CrossRef]

- Son, K.J. A Numerical Study of the Influence of Rheology of Cohesive Particles on Blade Free Planetary Mixing. Korea-Aust. Rheol. J. 2018, 30, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, K.J. A Discrete Element Model for the Influence of Surfactants on Sedimentation Characteristics of Magnetorheological Fluids. Korea-Aust. Rheol. J. 2018, 30, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, K.J. A Numerical Study of the Influence of Operating Conditions of a Blade Free Planetary Mixer on Blending of Cohesive Powders. Korea-Aust. Rheol. J. 2019, 31, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, G.G.; Nosonovsky, M. Contact Modeling—Forces. Tribol. Int. 2000, 33, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, D.L.; Tonks, D.L.; Wallace, D.C. Model of Plastic Deformation for Extreme Loading Conditions. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 93, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, O.S.; Ou, H.; Sun, W. Heat Generation, Plastic Deformation and Residual Stresses in Friction Stir Welding of Aluminium Alloy. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 238, 107827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, E.M.; Abraham, J.P.; Tong, J.C.K. Archival Correlations for Average Heat Transfer Coefficients for Non-Circular and Circular Cylinders and for Spheres in Cross-Flow. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2004, 47, 5285–5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, A.; Nikrityuk, P.A. Drag Forces and Heat Transfer Coefficients for Spherical, Cuboidal and Ellipsoidal Particles in Cross Flow at Sub-Critical Reynolds Numbers. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2012, 55, 1343–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, S. Forced Convection Heat Transfer Correlations for Flow in Pipes, Past Flat Plates, Single Cylinders, Single Spheres, and for Flow in Packed Beds and Tube Bundles. AIChE J. 1972, 18, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, F. Viscous Fluid Flow, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Higher Education: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Horban, B.A.; Fahrenthold, E.P. Hamilton’s Equations for Impact Simulations With Perforation and Fragmentation. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 2005, 127, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrenthold, E.P.; Horban, B.A. A Hybrid Particle-Finite Element Method for Hypervelocity Impact Simulation. Int. J. Impact Eng. 1999, 23, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.K.; Fahrenthold, E.P. A Kernel Free Particle-Finite Element Method for Hypervelocity Impact Simulation. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2005, 63, 737–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, B.; Muftu, S.; Gouldstone, A. Modeling of High Velocity Impact of Spherical Particles. Wear 2011, 270, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogacki, P.; Shampine, L.F. A 3(2) Pair of Runge - Kutta Formulas. Appl. Math. Lett. 1989, 2, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Zhong, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Jin, B.; Yuan, Z.; Lu, Y. CFD-DEM Simulation of Spouting of Corn-Shaped Particles. Particuology 2012, 10, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specification | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milling ball radius | R | 6.35 | mm |

| Cylindrical vial length | 58 | mm | |

| Vial inner contact area | 567.06 | ||

| Vial outer surface area | 567.06 | ||

| Vial oscillation amplitude | 25 | mm | |

| Vial oscillation frequency range | 90–130 | rad/s |

| Property | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | 7800 | ||

| Elastic modulus | E | 200 | GPa |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.3 | - | |

| Specific heat capacity | 461 |

| Property | Symbol 1 | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | 1.225 | ||

| Dynamic viscosity | 1.716 | Pa·s | |

| Thermal conductivity | k | 0.0241 | W/m·K |

| Specific heat capacity | 1003.5 | ||

| Sutherland constant | 111 | K | |

| Inward convection coefficient | 200 | ||

| Outward convection coefficient | 45 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation time | t | 60 | min |

| Coefficient of restitution | e | 0.7 | - |

| Collision heat generation ratio | 0.9 | - | |

| Heat division ratio | 0.368 | - | |

| Convection calibration factor | 0.3 | - |

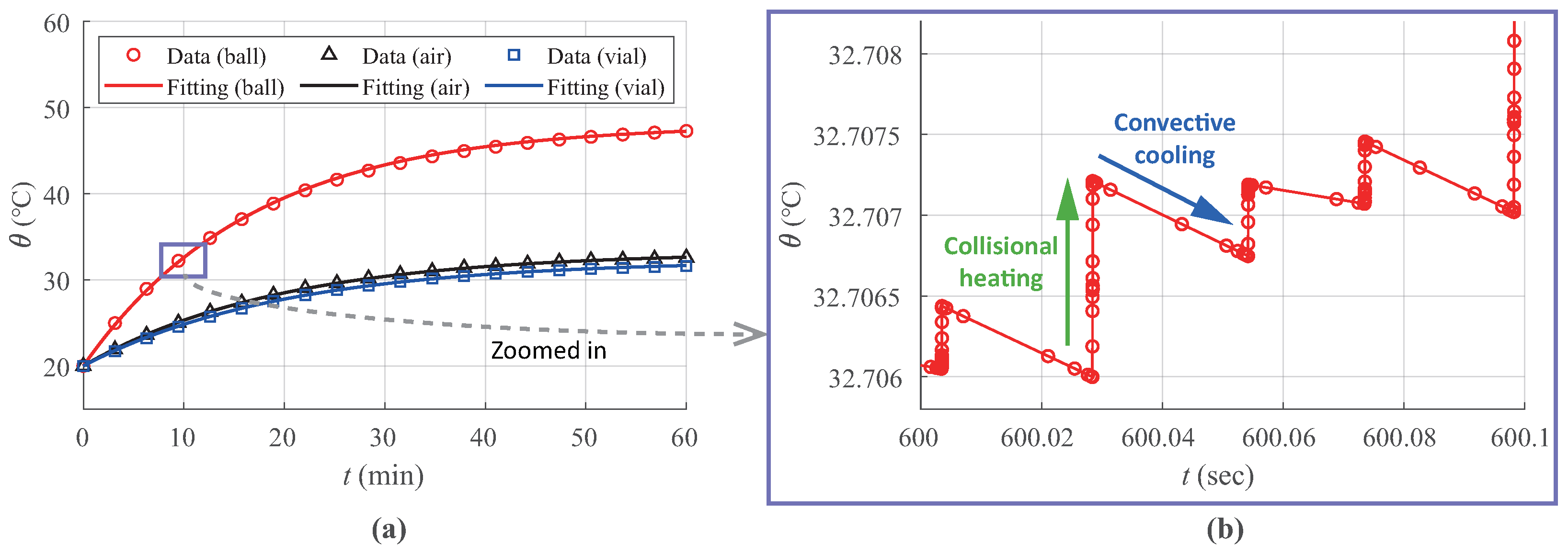

| Performance Metrics 1 | Experiment | Analysis | Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-state temperature (°C) | 48.0 | 47.89 | −0.24% |

| Time constant (min) | 16.7 | 16.70 | −0.03% |

| Initial temperature evolution rate (°C/min) | 1.6766 | 1.6702 | −0.58% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Son, K.J. Mathematical Modeling of High-Energy Shaker Mill Process with Lumped Parameter Approach for One-Dimensional Oscillatory Ball Motion with Collisional Heat Generation. Mathematics 2025, 13, 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13030446

Son KJ. Mathematical Modeling of High-Energy Shaker Mill Process with Lumped Parameter Approach for One-Dimensional Oscillatory Ball Motion with Collisional Heat Generation. Mathematics. 2025; 13(3):446. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13030446

Chicago/Turabian StyleSon, Kwon Joong. 2025. "Mathematical Modeling of High-Energy Shaker Mill Process with Lumped Parameter Approach for One-Dimensional Oscillatory Ball Motion with Collisional Heat Generation" Mathematics 13, no. 3: 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13030446

APA StyleSon, K. J. (2025). Mathematical Modeling of High-Energy Shaker Mill Process with Lumped Parameter Approach for One-Dimensional Oscillatory Ball Motion with Collisional Heat Generation. Mathematics, 13(3), 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13030446