Abstract

In this article, the special orthogonal group SO(3) is considered as a topological group. We show that SO(3) has the structure of a principal SO(2)-bundle over the sphere . As a consequence, we prove that every orbit of an SO(3)-action on a topological space is either trivial or homeomorphic to . We also introduce a topological atlas on SO(3), by means of its principal bundle structure, and prove that this atlas is smooth.

MSC:

15B10; 57R22

1. Introduction

This paper is devoted to the structure of the group of (real) special orthogonal matrices SO(3). This group carries several basic (compatible) mathematical structures—algebraic, topological and Lie group structures. Our main objective is to introduce on SO(3) the (topological) principal bundle structure, with structure group SO(2). We also discuss the smooth structure of SO(3).

Recall that a -matrix with real entries

is said to be special orthogonal if its entries satisfy the orthogonality conditions

and the determinant condition

The set of special orthogonal matrices endowed with the matrix multiplication is called the special orthogonal group (in three dimensions) and is denoted by SO(3).

This paper is a continuation of the paper by Krupka and Brajerčík [1]. In Section 2, Section 3 and Section 4, we briefly review basic topological concepts as needed in our proofs (fibrations, continuous group actions, homogeneous spaces and principal bundles); in general, our definitions follow Alperin, Bell [2], Dieudonné [3], Godbillon [4], Krupka and Krupková [5], Kurosh [6] and Warner [7].

Section 4 contains our first basic result. We prove that the cross-product mapping, assigning to a pair of orthogonal vectors their cross-product, is a fibration over the sphere with type fibre SO(2) (Theorem 1), and also a (right) principal SO(2)-bundle over (Theorem 2). This is based on a decomposition of the special orthogonal matrix in an explicit form (Lemma 6).

In Section 6, we introduce a (topological) atlas on SO(3). Our second main result is that the atlas is smooth (Theorem 6). Our aim is to complete the result to the atlases derived in Grafarend and Kuhnel [8], including explicit formulas. Following applications, the authors introduce in this paper four atlases, defined by parametrizations rather than charts. They arrive at a theorem on a minimal number of parametrizations (which is equal to 4). However, the compatibility of these atlases has not been discussed.

Applications of SO(3) have not been considered, although in contemporary mathematics and mathematical physics one should register, e.g., the Finsler geometry and the general relativity (see, e.g., Cheraghchi, Voicu and Pfeifer [9]; the Schwarzschild solution, Krupka and Brajerčík [10]; and the Birkhoff theorem).

The bold denoting the set of real numbers and its power should be retained. In this article, is the field of real numbers and is the real Euclidean vector space of dimension 3 endowed with the Euclidean scalar product. The first and the second Cartesian projections of the Cartesian product of two sets A and B are the mappings and . denotes the identity mapping of the set X. A section of a mapping is a mapping such that . A (topological) manifold is a locally Euclidean, second-countable, Hausdorff topological space. A topological group is a manifold endowed with a group structure compatible with its manifold structure.

2. Fibrations

Let Y and X be topological spaces and let be a continuous surjective mapping. Let Q be a topological space. By a Q-trivialisation of we mean a pair , where V is an open set in X and is a homeomorphism of and the Cartesian product .

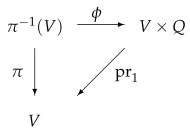

In short, we require that should satisfy the local triviality condition “V is open in X and is homeomorphic with the Cartesian product ”. If exists, we say that Y is Q-trivializable over V. In this case, we have a commutative diagram

or, which is the same,

on . Sometimes, when a continuous mapping is given and no confusion may arise, , or just , is called a Q-trivialisation of Y over V. We also say that Y is Q-trivial over V.

Clearly, for any , the fibre is homeomorphic with Q.

A Q-trivialisation is said to be global if . Existence of a global Q-trivialisation means that Y is homeomorphic with the Cartesian product .

By a Q-fibration structure on a topological space Y, we mean a topological space X, a continuous surjective mapping and a family of Q-trivialisations of such that the family covers X.

A topological space Y endowed with a Q-fibration structure , , is called a Q-fibration. Q is the type fibre, X is the base and is the projection of Y. The family is called the atlas of the Q-fibration Y.

The following is an immediate consequence of the definitions.

Lemma 1.

The projection π is an open mapping.

Proof.

Standard. □

In the following lemma, we show that the topology of the base X of a Q-fibration Y is uniquely determined by the topology of Y.

The final topology associated with is a topology on X, formed by the sets , such that is open in Y. Denote this topology by . Clearly, is the strongest topology on X in which is continuous: if is continuous with respect to a different topology on X, then necessarily .

Lemma 2.

The topology of the base X of a Q-fibration Y coincides with the final topology associated with the Q-projection .

Proof.

Let be the topology of X, and let be the final topology associated with . Let . Then, is open in Y. Since is open, the set is open in the topology . But by surjectivity of , ; thus, . On the other hand since , we have . □

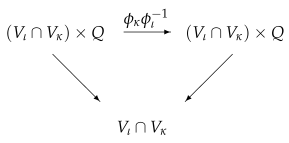

Let be an atlas of a Q-fibration Y. Consider any two charts , , and , , such that . Then, for every point ,

hence . Thus,

and

These formulas define a homeomorphism , the transition homeomorphism between the Q-fibration charts , and . This homeomorphism is represented by a commutative diagram

That is, in particular,

on , where for every the mapping restricted to the fibre over x is a homeomorphism of Q. In other words, the family labelled by is a family of homeomorphisms of Q.

3. Actions of Topological Groups

3.1. Actions of Topological Groups on Topological Spaces

A group structure and a topological structure on a set G are said to be compatible if the group multiplication and the inversion are continuous. By a topological group we mean a set endowed with compatible group and topological structures.

Let G be a topological group and the identity element of G. By a right action of G on a topological space Y we mean a continuous mapping such that and for all and all . The G-orbits of the points , are equivalence classes of equivalence relation “ if there exists such that ”; the corresponding quotient set is denoted by , and is the corresponding quotient projection. The set , endowed with the quotient topology, the strongest topology in which is continuous, is called the orbit space.

is an open mapping. Indeed, for an open set , its saturation

is a union of open sets and is therefore open; then, however, is by definition open in the quotient topology.

Any point defines a surjective mapping called the G-orbit mapping passing through the point y. Clearly, is continuous and

Analogously, by a left action of G on a topological space Y we mean a continuous mapping such that and for all and all . The concepts of a G-orbit and the orbit space of a left action are defined as in the case of a right action.

Given a left action , any point defines a surjective mapping called the G-orbit mapping passing through . Clearly, is continuous and

The right and left group actions may have additional properties. In the next two subsections, specific cases needed in this article are introduced.

3.2. Principal G-Bundles

A right action is said to be free if for any , the equation has a unique solution ; equivalently, we say that G acts on Y freely, or without fixed points.

A right action is said to be principal if it is free and the following local triviality condition is satisfied: For every point there exist a G-invariant neighbourhood W of and a homeomorphism such that for all and all

and

A topological space Y endowed with a principal right action of a topological group G is called a principal G-bundle, or just a principal bundle if no misunderstanding may arise. G is called the structure group, the orbit space the base and the quotient projection the projection of the principal G-bundle Y.

Clearly, a principal G-bundle is a G-fibration. The -saturated sets are exactly the G-invariant sets; the G-trivialisations are the homeomorphisms .

Remark 1.

For any topological space X and any topological group G, the canonical right group action of G on the Cartesian product is principal, and defines on the canonical principal G-bundle structure.

By a principal G-bundle chart on a principal G-bundle Y we mean any pair , where W is a G-invariant open set in Y and is a G-equivariant G-trivialisation. An atlas for Y is a collection of principal G-bundle charts such that .

We shall determine the transition homeomorphisms (1) for a principal G-bundle atlas . Denote for all and express as

where is the principal part of the G-trivialisation . Conditions (2) and (3) imply

for all and all .

Lemma 3.

For any two principal G-bundle charts and such that , the mapping is constant along the fibres over .

Proof.

Let and let . Then, for some ; hence, by (4),

□

Set for any and any

By Lemma 3, Formula (5) defines a continuous mapping .

Lemma 4.

The transition homeomorphism is of the form

Proof.

By definition , , and using (5)

But also ; hence, as required. □

Remark 2.

For transition G-homeomorphisms (6), determine sections of the trivial principal G-bundles . Thus, a necessary and sufficient condition for the principal G-bundle Y to be trivial is the existence of a global continuous section of Y.

3.3. Left Actions: Subgroup Orbit Structure

The orbit stabilizer theorem as formulated in Krupka and Brajerčík [1], Section 2.3, can be easily extended to topological groups. Recall basic concepts within the category of topological spaces. Let Y be a topological space endowed with a continuous left action of a topological group G. Choose and set, for every ,

is the G-orbit mapping passing through the point . Clearly, for all ; in particular, is G-equivariant.

As before, let be the orbit stabilizer of the point . If , then .

Lemma 5.

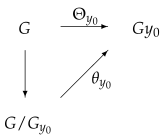

For any point , there exists a unique G-equivariant homeomorphism such that the diagram

commutes.

4. Principal Bundle Structure of SO(3)

4.1. The SO(2)-Fibration Structure on SO(3)

Recall the definition of the cross-product mapping (Krupka, Brajerčík [1], Section 3.3). For any special orthogonal matrix expressed by

is defined to be the first column vector in ; for convenience, we also write as a raw vector,

By special orthogonality of ,

can also be viewed as the restriction to SO(3) of the Cartesian projection of a -matrix onto its first column followed by the restriction of its range to its image . is obviously surjective and continuous.

Our objective in this subsection is to demonstrate that the cross-product mapping defines on SO(3) the structure of an SO(2)-fibration.

We consider with its canonical coordinates x, y and z; then, the unit sphere is the set . Our constructions are based on an observation that any vector , such that and , satisfies

In particular, we have a mapping

or, in an obvious sense, a section of the cross-product over the set where . Analogous sections arise on the subsets of the sphere where or .

Recall that the cyclic permutation matrices are defined by

These matrices constitute a subgroup of SO(3). The group multiplication yields . For any written as (7), we have

In particular, if

then

Lemma 6.

Any matrix admits the following decompositions in the group SO(3):

(a) If , then

(b) If , then

(c) If , then

Proof.

(a) Clearly, under assumption , the matrix

satisfies and , so it is special orthogonal. Since the inverse of a special orthogonal matrix coincides with its transpose, we have the identity

Calculating the product of the first two matrices,

But from

and from the orthogonality conditions

hence

This formula already proves (9).

(b) If , we repeat the calculation in part (a) of this proof for the matrix

Performing the corresponding replacements in (9),

To return to , we multiply by . Since

then

proving (10).

(c) Replace in part (b) of the proof by the permutation matrix . □

Denote

and

are open sets in SO(3), are open sets in , and

Consider the mappings

and the pairs , , .

Lemma 7.

The mappings are homeomorphisms. The inverse mappings , , are given by

Proof.

We show that , and are bijective. It is sufficient to verify that , and are surjective and , and .

We prove the surjectivity of . Choose a point

such that . Then, equation

has a unique solution

proving the surjectivity of . The same is obviously true for and and .

We can now conclude this subsection by the following theorem.

Theorem 1.

The cross-product defines on the structure of an -fibration.

Proof.

It is immediately verified that the topological space SO(3), the mapping and the family of trivialisations satisfy the axioms of an SO(2)-fibration. □

4.2. The Principal SO(2)-Bundle Structure on SO(3)

In this subsection, we consider a continuous right action of SO(2) on SO(3) given by

We show that this right group action is principal and find an explicit formula for the corresponding quotient projection.

First, let us examine the equivalence relation on SO(3) “ if there exists a matrix such that ”.

Lemma 8.

Let be any matrices,

The following conditions are equivalent:

(a) for some .

(b)The entries of τ and κ satisfy

Proof.

Equation is of the form

□

Lemma 8 states, in particular, that and belong to the same SO(2)-orbit if and only if the first columns in their matrix expressions (21) coincide.

Lemma 9.

Suppose that , , . Then, ν exists and is uniquely determined by κ and τ. In components

Lemma 10.

The quotient SO(3)/SO(2) can be identified with the sphere and the quotient projection of SO(3) onto SO(3)/SO(2) with the cross-product .

Proof.

By Lemma 8, the quotient projection assigns to a matrix

in the first column of , the vector . But this is exactly the cross-product (8). □

Theorem 2.

The special orthogonal group SO(3) endowed with the right SO(2)-action (20) is a principal SO(2)-bundle.

Proof.

Since the action (20) is defined by multiplication of non-singular matrices, it is obviously free. It remains to show that it satisfies the local triviality condition.

For every point , there exist an SO(2)-invariant neighbourhood W of and a homeomorphism such that for all

and that for all and all

It is sufficient to verify that the mappings (14)–(16) are SO(2)-equivariant. is given by

where . It follows from Formula (20) that the open set is SO(2)-invariant. To verify that , we express as

and as

We obtain the decomposition for

Then, however,

□

Remark 3.

Obviously, Theorem 2 can be expressed mutatis mutandis when we replace the first column vector by an arbitrary column vector, or arbitrary raw vector, or we replace τ by .

5. Orbits of SO(3)

5.1. Connected Subgroups of SO(3)

The following theorem classifies all connected subgroups of the special orthogonal group SO(3). Its proof is based on the use of the (continuous) trace function . Let , and be the elementary special orthogonal groups formed by the matrices

where

Theorem 3.

The only connected subgroups of SO(3) different from the identity subgroup are elementary special orthogonal groups , and ; conjugate subgroups of , and ; and the group SO(3).

Proof.

Let G be a non-trivial connected subgroup of SO(3). Since any subgroup contains the identity element I of SO(3) and , the image in contains the right endpoint 3 of the interval . Since the mapping tr is continuous and G is connected, then is connected in . But non-trivial connected subsets of an interval in are always intervals; thus, must be of the form or , where . □

Remark 4.

Theorem 3 provides a classification of subgroups of the special orthogonal group SO(3). We have the following list of subgroups :

- (a)

- The trivial subgroup (the unit matrix);

- (b)

- Subgroups formed by elementary special orthogonal matrices (generated by the group SO(2)) and their conjugate subgroups;

- (c)

- SO(3);

- (d)

- Finite subgroups;

- (e)

- Non-connected subgroups whose connected components are generated by the group SO(2) (subgroups generated by O(2)).

5.2. Orbits of SO(3)

Let Y be a topological space endowed with a continuous left action of the special orthogonal group SO(3). Consider an SO(3)-orbit , where , and the corresponding orbit mapping

Clearly, is constant on the left cosets , where is the stabilizer of the point : for any

Thus, Formula (24) gives rise to a commutative diagram

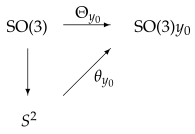

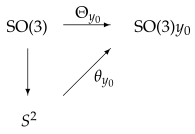

defining a mapping . By Lemma 5, is an SO(3)-equivariant homeomorphism defined uniquely by the commutativity of (25).

defining a mapping . By Lemma 5, is an SO(3)-equivariant homeomorphism defined uniquely by the commutativity of (25).

As a subgroup of SO(3), the stabilizer coincides with a subgroup of SO(3) (Remark 3); in particular, topological properties of the SO(3)-orbit are completely determined by .

Theorem 4.

Suppose that the stabilizer is homeomorphic to a subgroup of SO(3) generated by the group SO(2). Then, the orbit is homeomorphic with the sphere .

Proof.

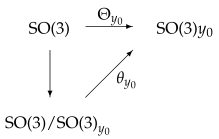

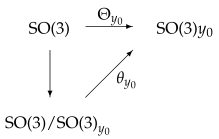

SO(3) has the structure of a principal SO(2)-bundle over the sphere , with the principal bundle projection (Theorem 2). If by assumption is a subgroup of type (b) in the list given by Remark 4, then and diagram (25) becomes

as required. □

Theorem 5.

Let be a left action of the special orthogonal group on a topological space Y. Suppose that for every point the orbit stabilizer is a connected subgroup of different from . Then, is isomorphic with and the orbit is isomorphic to the sphere .

Proof.

Theorem 5 is an immediate consequence of Theorems 4 and 3. □

6. Smooth Structure of SO(3)

To complete the discussion of the topological structure of SO(3), we prove the existence of a smooth atlas on SO(3), turning the set SO(3) into a smooth manifold of dimension 3. Our aim is to introduce an atlas consisting of a minimum number of charts, called a minimal atlas. This number is determined by the Lusternik–Schnirelmann category cat X of a manifold X [11]. This topological invariant of a given manifold X is defined as the minimum number n such that there is a covering of X by n open sets, each of which can be contracted to a point inside X. Since (see [8]), a minimal atlas on SO(3) consists of four charts.

The construction of a minimal atlas of SO(3) is analogous to the construction of a minimal atlas on the unit sphere . The fact gives us that a minimal atlas on consists of two charts. For such construction, the spherical coordinates, or the stereographic projections from two poles, can be employed.

In this paper, by a chart on a topological n-manifold X we mean a pair , where U is an open subset of X, and is a homeomorphism of U and an open ball in (compare with [8]). Two charts, and , are said to be smoothly compatible if either or the map is a diffeomorphism. A smooth atlas for X is a collection of charts whose domains cover X and each pair of the charts is smoothly compatible.

To introduce a smooth atlas on SO(3) explicitly, we use the decomposition of (7) given by Lemma 6. If , then

Note that and the first factor of the decomposition (26) have the same first column , which can be identified with an element of . Using the first chart on (see, e.g., [10]), we have

where , .

Second factor of the decomposition (26) can be interpreted as an element of SO(2). So, we can assign to this element such that

Then,

and is uniquely determined by its first column and its third row . Indeed, from (26), we have

So, there is a correspondence between the triples and the matrices in the form

which can be considered as the mapping , .

Lemma 11.

Proof.

Remark 5.

Lemma 11 is valid when the interval is replaced by any interval of length .

Let us denote . From Lemma 11, the mapping is injective and continuous. Denoting , the inverse of is the mapping ,

given by

is continuous. Thus, is a homeomorphism, and we have completed the proof.

Lemma 12.

The pair , , is a chart on .

Next, we introduce the mapping on W defined by

Since restricted to the set is injective and continuous, is also injective and continuous. Denoting , the mapping , , is the inverse of given by

Lemma 13.

The pair , , is a chart on . Charts and are smoothly compatible.

Proof.

Since is continuous, is a homeomorphism.

Coordinate transformation is given by

Analogously, coordinate transformation is given by

Obviously, first partial derivatives of and are constant; and are diffeomorphisms on and , respectively, and . □

If , by Lemma 6 we have

Using the second chart on (see, e.g., [10]), we have

where , .

The second factor of the decomposition (29) can be interpreted as an element of SO(2). So, we can assign to this element such that

Then,

and is uniquely determined by its first column and second row . Indeed, from (29), we have

So, there is a correspondence between the triples and the matrices in the form

which can be considered as the mapping , .

Lemma 14.

Proof.

Remark 6.

Lemma 14 is valid when the interval is replaced by any interval of length .

Let us denote . From Lemma 14, the mapping is injective and continuous. Denoting , the inverse of is the mapping ,

given by

Lemma 15.

The pair , , is a chart on .

Proof.

is continuous; thus, it is a homeomorphism on an open subset of . □

Now, we introduce the mapping on W defined by

Since restricted to the set is injective and continuous, is also injective and continuous. Denoting , the mapping , , is the inverse of given by

Lemma 16.

The pair , , is a chart on . Charts , are smoothly compatible.

Proof.

Analogous to the proof of Lemma 13. □

From the definition of , , and we obtain their explicit description,

Lemma 17.

The sets cover SO(3).

Proof.

Denoting

we get

Since any matrix does not have the column consisting of all zeros, we get . Also, the pairs of conditions , and , cannot be fulfilled simultaneously, so and , respectively. Finally because it is impossible to have and for any matrix . Thus, a complement of the union in SO(3) is an empty set. □

Theorem 6.

The charts , , and represent a smooth atlas on SO(3).

Proof.

According to Lemma 17, . It should be shown that each pair of these charts is smoothly compatible. In Lemmas 13 and 16, it is shown that the pairs , and , , respectively, are smoothly compatible charts.

Now, let us consider the mapping . As a composition of homeomorphisms, is also a homeomorphism; its inversion is .

We have to show that the mapping and its inversion are . Concrete calculations are omitted. Using (7), (27) and (32), we obtain coordinate expression of ,

Let us determine partial derivatives of . Obviously,

Moreover,

For , we have , and

For , we have , and

so finally, on , we have

Analogously, on we obtain

Obviously, all partial derivatives of on of all orders exist and are continuous; thus, is smooth.

Coordinate expression of is given by mutual exchange of the indices 1 and 3 in (33). Thus, is smooth, which implies that the charts and are smoothly compatible. We have analogous results for other pairs of charts, namely and ; and ; and . □

Remark 7.

Using parametrizations, Grafarend and Kuhnel in [8] introduced four types of minimal atlases on SO(3), each consisting of four coordinate charts. For example, one of them, the atlas consisting of charts given by Cardan angles, belongs to the same smooth structure on SO(3) as represented by the atlas in Theorem 6.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, original draft preparation and preparation of comments on reviews of the paper equally. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Transilvania Fellowship Program for Visiting Professors. The second author (D.K.) highly appreciates the excellent research conditions extended to him by the Department of Mathematics and Computer Science of the Transilvania University in Brasov, Romania.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Krupka, D.; Brajerčík, J. On the Structure of SO(3): Trace and Canonical Decompositions. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1490. [Google Scholar]

- Alperin, J.L.; Bell, R.B. Groups and Representations; Graduate Texts in Mathematics 162; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dieudonné, J. Treatise on Analysis; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972; Volume III. [Google Scholar]

- Godbillon, C. Géométrie Différentielle et Mécanique Analytique; Hermann: Paris, France, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Krupka, D.; Krupková, O. Topology and Geometry; Lectures and Solved Problems; SPN: Praha, Czechia, 1989. (In Czech) [Google Scholar]

- Kurosh, A. Higher Algebra; Mir Publishers: Moscow, Russia, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, F.W. Foundations of Differentiable Manifolds and Lie Groups; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Grafarend, E.W.; Kuhnel, W. A minimal atlas for the rotation group SO(3). Int. J. Geomath 2011, 2, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghchi, S.; Voicu, N.; Pfeifer, C. Four-dimensional SO(3)-spherically symmetric Berwald Finsler space. Int. J. Geom. Method Mod. Phys. 2023, 20, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupka, D.; Brajerčík, J. Schwarzschild spacetimes: Topology. Axioms 2022, 11, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusternik, L.; Schnirelmann, L. Sur un principe topologique en analyse. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 1929, 188, 295–297. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).