Research on the Factors of Competition in the Green Procurement Processes: A Case Study for the Conditions of Romania Using PLS-SEM Methodology

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“a process whereby public and semi-public authorities meet their needs for goods, services, works and utilities by seeking and choosing outcomes and solutions that have a reduced impact on the environment throughout their whole life-cycle, as compared to conventional products/solutions. A procurement procedure will be considered as ‘green’ only if it has led to the purchase of a substantively ‘greener’ product and only if the environmental characteristics of this product go beyond what needs to be complied with on the basis of European or national environmental legislation.”[5]

2. Impact of Green Procurement on Competition, Reflected in the Economic Literature and the Hypotheses Development

- contracts for the acquisition of goods, in which case the selection of offers will take into account the life cycle of the product, respectively the opportunities for reuse of the goods offered, specific to the circular economy and the impact of the re-use process on the environment;

- service provision contracts, by contracting the technical expertise in the field of environmental protection, and;

- works contracts, which should be based on impact studies on the quality of environmental factors.

3. Econometric Analysis of the Behavioral Model

3.1. Theory of Rational Behavior in Economic Modeling

3.2. Research Methodology

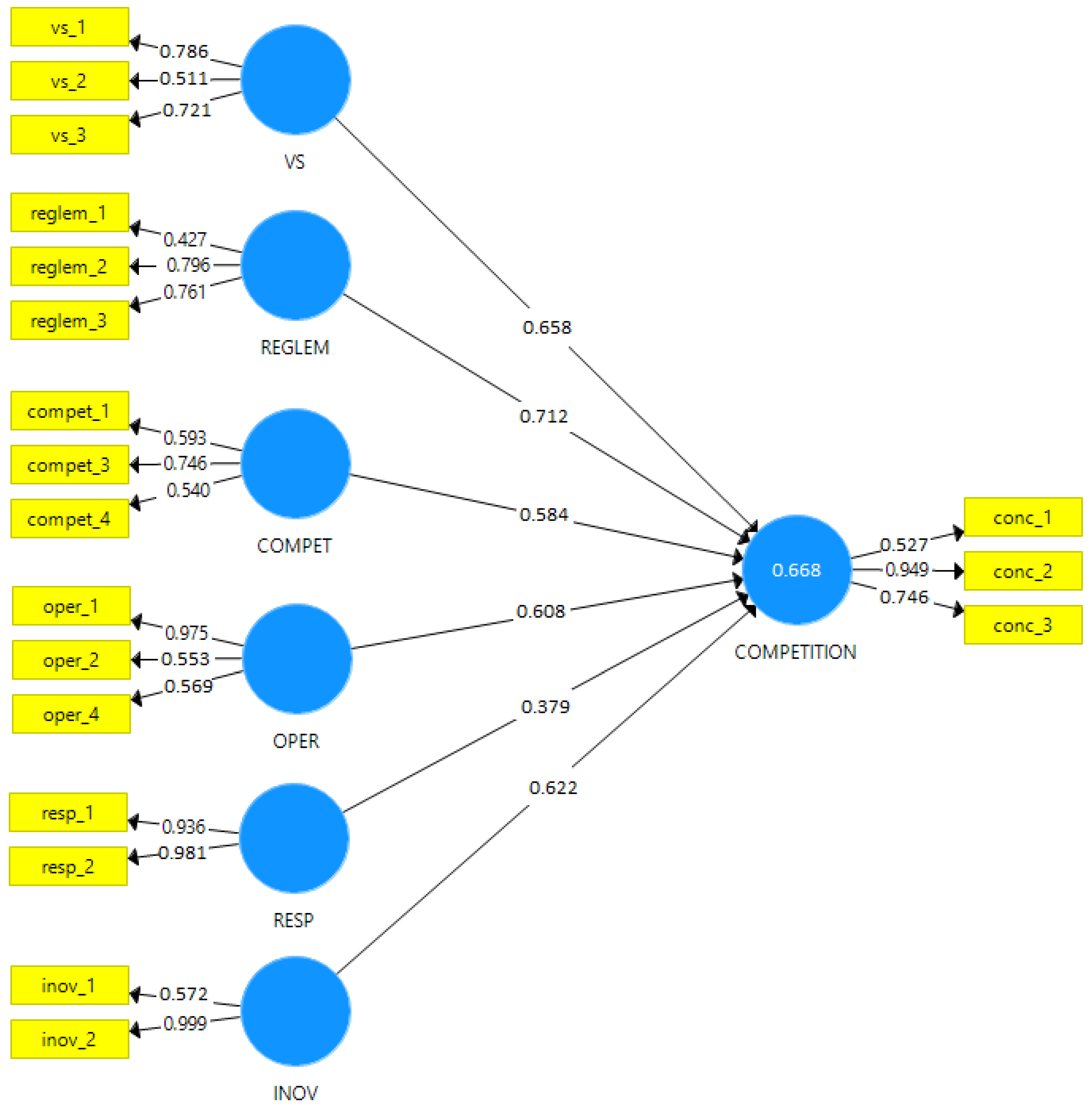

4. Model Estimation and Results

4.1. Measurement Models

4.1.1. Construct Validity

4.1.2. Divergent Validity

4.2. Structural Model

- δ-the vector for the endogenous latent variables;

- ϕ-the vector for the exogenous latent variables;

- Σ-the residual variable vector;

- Λ and Γ–matrices of the path coefficients.

5. Results and Discussions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- COM. Interpretation of the Commission Regarding the Integration of Environmental Considerations in Public Procurement Procedures. 2001. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/guides/public_procurement/2018/guidance_public_procurement_2018_ro.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- COM. 400—Public Procurement for Better Environmental Conditions. 2008. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/archives/gpp/buying_green_handbook_ro.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Directive UE no. 24/2014 Regarding Public Procurement, Transposed at National Level by Law no. 98/2016 Regarding Public Procurement, OUG no. 107/2017, OUG no. 45/2018, Respective HG no. 395/2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/RO/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32014L0024 (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- Directive UE no. 23/2014 Regarding the Award of Concession Contracts, Transposed by Law no. 100/2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/RO/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AJOL_2014_094_R_0001_01 (accessed on 18 July 2019).

- Directive UE no. 25/2014 Regarding the Acquisitions Made by the Entities that Operate in the Water, Energy, Transport and Postal Services Sectors, Transposed by Law no. 99/2016 Regarding Sectoral Acquisitions, Respectively by GD no. 394/2016 Regarding the Approval of the Implementing Norms Regarding the Award of Sectoral Contracts. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/RO/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0025&from=EN (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- EC. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee Of the Regions. 2008. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/pdf/sec_2008_2124_EN.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- UN. MATTM & United Nations Environment Programme, 2017—Financing the Future: Report of the Italian National Dialogue on Sustainable Finance. 2016. Available online: http://unepinquiry.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/02/Financing_the_Future_EN.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- EC. Paris Agreement on Climate Change. 2018. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/climate-change/timeline/ (accessed on 24 July 2019).

- Brännlund, R.; Lundberg, S.; Marklund, P.O. Assessment of Green Public Procurement as a Policy Tool: Cost-Efficiency and Competition Considerations; Umea Economic Studies Umea University, 2009; Available online: http://ippa.org/images/PROCEEDINGS/IPPC4/07GreenProcurement/Paper7-1.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2019).

- Aldenius, M.; Khan, J. Strategic use of green public procurement in the bus sector: Challenges and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peprah, J.A.; Brako, S.; Akosah, N.B. The Awareness Level of Green Procurement at the District Assemblies in Western Region in Ghana. J. Manag. Sustain. 2018, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michelsen, O.; de Boer, L. Green procurement in Norway; a survey of practices at the municipal and county level. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meehan, J.; Bryde, D. Sustainable procurement practice. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. Buying Green! A Handbook on Green Public Procurement. 2011. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/pdf/Buying-Green-Handbook-3rd-Edition.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2019).

- Romanian Competition Law. 1996. Available online: http://www.consiliulconcurentei.ro/uploads/docs/items/bucket8/id8047/lege_nr21_1996_actualizata_20160303.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- OECD. Competition and Procurement. Key Findings. 2011. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/sectors/48315205.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Jevons, W.S. Notice of a general mathematical theory of political economy. J. Statistical Soc. Lond. 1862, 70–77. Available online: https://www.peterharrington.co.uk/notice-of-a-general-mathematical-theory-of-political-economy-123182.html (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Menger, C. Principles of Economics; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1871. [Google Scholar]

- Walras, L. Éléments D’économie Politique Pure. 1874. Available online: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00508902/document (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- Friedman, M.; Savage, L.J. The utility analysis of choices involving risk. J. Political Econ. 1984, 56, 279–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, Mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. One-tailed or two-tailed P values in PLS-SEM? Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busu, C.; Busu, M. Economic modeling in the management of transition to bioeconomy. Amfiteatru Econ. 2019, 21, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Henseler, J.; Hair, J.F. On the emancipation of PLS-SEM: A commentary on Rigdon. Long Range Plan. 2014, 47, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.K. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Oztekin, A.; Delen, D.; Turkyilmaz, A.; Zaim, S. A machine learning-based usability evaluation method for eLearning systems. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzo, N. A preliminary Quantitative Analysis of Rural Development in Romania Using the PLS-SEM. Albanian J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 17, 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Avkiran, N.K.; Ringle, C.M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Recent Advances in Banking and Finance; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ryu, K. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garson, G.D. Partial Least Squares Regression and Structural Equation Models; Statistical Associates: Asheboro, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ramayah, T.; Cheah, J.-H.; Chuah, F.; Ting, H.; Memon, M.A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using SmartPLS 3.0: An Updated and Practical Guide to Statistical Analysis; Pearson: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ali, F. Editorial: Partial least squares (PLS) in hospitality and tourism research. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2018, 9, 238–248. [Google Scholar]

- Shiau, W.-L.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F. Editorial: Internet research using Partial Least squares Structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Internet Res. Forthcom. 2019, 29, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, H.O.A. Partial least squares. In Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences; Kotz, S., Johnson, N.L., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 581–591. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Salzberger, T.; Baumgartner, P. Selecting single items to measure doubly-concrete constructs: A cautionary tale. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3159–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E. Rethinking partial least squares path modeling: In praise of simple methods. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common beliefs and reality about partial least squares: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wold, H. Soft modeling: The basic design and some extensions. Syst. Indirect. Obs. 1982, 2, 343. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 566–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Frye, T. PLS Graph–Version 3.0. Soft Modeling Inc. Available online: http://www.plsgraph.com (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 3; SmartPLS GmbH: Boenningstedt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Monecke, A.; Leisch, F. SemPLS: Structural equation modeling using partial least squares. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rigdon, E.E. Choosing PLS path modeling as analytical method in European management research: A realist perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, N.F.; Cepeda-Carrión, G.; Roldán Salgueiro, J.L.; Ringle, C.M. European management research using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nitzl, C. The use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in management accounting research: Directions for future theory development. J. Account. Lit. 2016, 37, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Valle, P.O.; Assaker, G. Using partial least squares structural equation modeling in tourism research: A review of past research and recommendations for future applications. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.; Da Silva, D.; Bido, D. Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS. Braz. J. Mark. 2014, 13, 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, K.; Eskildsen, J. Design of PLS-Based Satisfaction Studies. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 247–277. [Google Scholar]

- Memmott, J.; Cadotte, M.; Hulme, P.E.; Kerby, G.; Milner-Gulland, E.J.; Whittingham, M.J. Putting applied ecology into practice. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 47, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, N.A.; Pelau, C. Correlations within the EFQM business excellence model by applying a factor analysis. Amfiteatru Econ. 2017, 19, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chalikias, M.S. Optimal Designs for Carry Over Effects the Case of Two Treatment and Four Periods. Mathematics 2019, 7, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dinu, V. Quality Management and Business Excellence. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2017, 19, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Andrecka, M. Corporate social responsibility and sustainability in Danish public procurement. Eur. Procure. Pub. Private Partnersh. L. Rev. 2017, 12, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.K.; Pookayaporn, J. Economic value added and ecology value added as a measure for disaster preparedness linked to corporate social responsibility: Japan as a test-bed bridging Asia and North America. Int. J. Bus. Emerg. Mark. 2018, 10, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, N.P.; Pyenson, N.D. Evolutionary innovation and ecology in marine tetrapods from the Triassic to the Anthropocene. Science 2015, 348, 3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Witjes, S.; Lozano, R. Sustainable Public Procurement: Moving to more sustainable societies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 85–95. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sjors_Witjes/publication/310142630_Sustainable_Public_Procurement_Moving_to_more_sustainable_societies_-_Virtual_Special_Issues_-_Elsevier/links/5829a6b508aefcbdb47fd5bf.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- ZeinEldin, R.A.; Chesneau, C.; Jamal, F.; Elgarhy, M. Statistical Properties and Different Methods of Estimation for Type I Half Logistic Inverted Kumaraswamy Distribution. Mathematics 2019, 7, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacaskul, P. Financial Risk Management and Sustainability. The Sufficiency Economy Philosophy Nexus. 2017. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3057886 (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Chin, W.W. How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandia, J.; Steijn, B.; Kuipers, B. It is not easy being green: Increasing sustainable public procurement behaviour. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 28, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernandez, A.A.; Ona, S.E. A Qualitative Study of Green IT Adoption within the Philippines Business Process Outsourcing Industry: A Multi-Theory Perspective. Int. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2015, 11, 28–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.W.; Dickinson, N.M.; Chan, G.Y. Green procurement in the Asian public sector and the Hong Kong private sector. In Natural Resources Forum; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2010; Volume 34, pp. 24–38. [Google Scholar]

| Strategic Vision (SV) | |

| vs_1 | Existence of priority environmental objectives, made aware at the organization level (on a top-down scale), through programs to streamline the use of resources |

| vs_2 | The existence of a cooperation partnership in the field of sustainable economy with organizations in the public and/or private environment (chambers of commerce, entrepreneurs’ associations, universities, central or local public authorities, etc.) |

| vs_3 | Existence of a management strategy oriented to reintegration programs of the resources used in the production circuit |

| vs_4 | Participation in the green procurement procedures organized by the public authorities |

| Reglementation (Reglem) | |

| Reglem_1 | Funding programs from European and/or national public funds |

| Reglem_2 | Economic incentives provided for in national legislation, favorable to investments in “green” projects |

| Reglem_3 | Existence of a legal framework adopted in the field of green procurement |

| Competences (Compet) | |

| Compet_1 | Participation in discussion forums and information exchanges with profile organizations, to transfer knowledge of developments and expertise in the field of green procurement |

| Compet_2 | Training courses for specialists in the field of environmental policy and public procurement, especially in the field of green procurement |

| Compet_3 | Knowledge of specific and/or functional criteria in the field of green procurement that ensures compliance with the legislation in the field |

| Compet_4 | Innovative technologies research to reduce energy consumption, extend product life, and reuse resources |

| Integrated operational management (Oper) | |

| Oper_1 | Existence of a procurement and strategy department to respond adequately to external requests (business partners, public authorities, etc.) |

| Oper_2 | Existence of a logistics department, responsible for packing, recycling, resource reuse, low energy consumption, etc. |

| Oper_3 | The existence of an applied research department, which integrates innovative products and/or technologies in the production circuit |

| Oper_4 | The existence of an integrated data flow, available to the directorates within the organization |

| Social responsibility (Resp) | |

| Resp_1 | Carrying out campaigns of social involvement, by presenting the benefits of green acquisitions |

| Resp_2 | CSR and ethics programs at the organization level |

| Resp_3 | Incentives provided to employees for compliance |

| Innovation (Inov) | |

| Inov_1 | Holding certifications in the field of organic production (for example, the use of eco-label labels) |

| Inov_2 | Holding patents/licenses for environmentally friendly technologies |

| Endogenous Variable: Competition Degree | |

|---|---|

| Conc_1 | Number of competitors in the green procurement market |

| Conc_2 | The price offered for green purchases versus the reference price on the market |

| Conc_3 | The degree of concentration on the green procurement market |

| Variable | Dillon Golsteins’ Rho | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VS | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 2.131 |

| REGLEM | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.548 |

| COMPET | 0.687 | 0.708 | 0.835 | 0.708 | 1.476 |

| OPER | 0.637 | 0.732 | 0.682 | 0.684 | 2.674 |

| RESP | 0.626 | 0.756 | 0.664 | 0.624 | 2.386 |

| INOV | 0.645 | 0.789 | 0.678 | 0.618 | 2.274 |

| Latent Variables | AVE | The Square Root of the Correlation Coefficients between Latent Variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SV | Reglem | Compet | Oper | Resp | Inov | ||

| VS | 1.000 | 1 | |||||

| REGLEM | 1.000 | 0.621 | 1 | ||||

| COMPET | 0.825 | 0.679 | 0.512 | 1 | |||

| OPER | 0.748 | 0.528 | 0.491 | 0.531 | 1 | ||

| RESP | 0.729 | 0.683 | 0.608 | 0.596 | 0.612 | 1 | |

| INOV | 0.688 | 0.602 | 0.543 | 0.580 | 0.602 | 0.548 | 1 |

| Research Hypothesis | Coefficients | Standard Error | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Strategic Vision -> Green procurement competition | 0.658 | 0.246 | 3.648 | 0.005 |

| H2: Regulation -> Green procurement competition | 0.712 | 0.278 | 2.831 | 0.029 |

| H3: Competence -> Green procurement competition | 0.584 | 0.202 | 3.289 | 0.009 |

| H4: Operational -> Green procurement competition | 0.608 | 0.209 | 2.405 | 0.036 |

| H5: Responsibility -> Green procurement competition | 0.379 | 0.247 | 1.789 | 0.242 |

| H6: Innovation -> Green procurement competition | 0.622 | 0.248 | 3.234 | 0.008 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Busu, C.; Busu, M. Research on the Factors of Competition in the Green Procurement Processes: A Case Study for the Conditions of Romania Using PLS-SEM Methodology. Mathematics 2021, 9, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9010016

Busu C, Busu M. Research on the Factors of Competition in the Green Procurement Processes: A Case Study for the Conditions of Romania Using PLS-SEM Methodology. Mathematics. 2021; 9(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleBusu, Cristian, and Mihail Busu. 2021. "Research on the Factors of Competition in the Green Procurement Processes: A Case Study for the Conditions of Romania Using PLS-SEM Methodology" Mathematics 9, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9010016

APA StyleBusu, C., & Busu, M. (2021). Research on the Factors of Competition in the Green Procurement Processes: A Case Study for the Conditions of Romania Using PLS-SEM Methodology. Mathematics, 9(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9010016