Reverse Causality between Fiscal and Current Account Deficits in ASEAN: Evidence from Panel Econometric Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- (1)

- The first situation refers to Keynesian absorption theory (1936), according to which an increase in fiscal budget leads to an increase in aggregate demand which in turn puts upward pressure on imports and causes an increase in CAD. According to Mundell and Fleming’s theory, an increase in fiscal deficit puts upward pressure on the interest rate, this, in turn, induced an increase in the capital inflow and appreciation in the exchange rate. This channel ultimately exacerbates the trade balance. Therefore, the first possibility indicates that causality runs from FD to CAD.

- (2)

- The second possible outcome refers to the Ricardian Equivalence (RE) theory, according to this theory, an increase in tax rate can contract the fiscal deficit but may not change the trade balance. The RE theory suggests that an increase in the fiscal deficit will not alter the capital inflows and level of aggregate demand [10]. Basic RE theory implies that due to the budget deficit, there is a decrease in government savings which is completely offset by a high level of private savings. Hence, aggregate demand is not changed [11]. Thus, the second possibility refers to no causality between CAD and FD.

- (3)

- The third possible outcome refers to the neo-classical view [12] that the fiscal deficit can be used as an instrument to achieve the current account balance. The government uses its fiscal policy to regulate the external balance. In this case, the government has the aim to reduce the current account balance. This case refers to reverse causality, in which causality runs from current account deficit to fiscal deficits. This is known as the current account targeting hypothesis (CATH) where unidirectional causality runs from CAD to FD.

- (4)

- The fourth possibility is bidirectional causality between FD and CAD. Causality from CAD to FD refers to external adjustments through fiscal policy, while causality from FD to CAD may result because of significant feedback. So in this way, bidirectional causality may occur between FD and CAD [13].

3. Methods

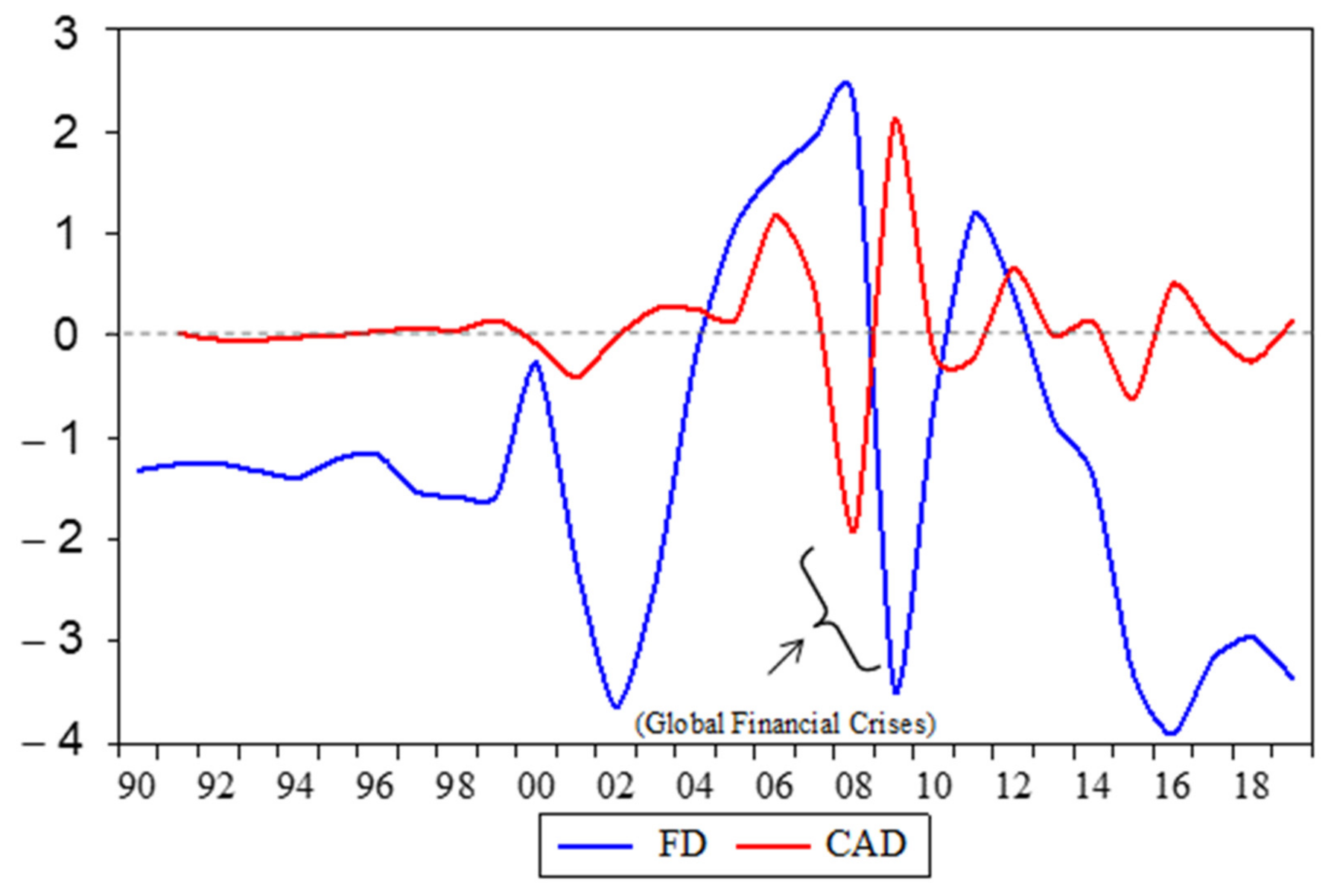

3.1. Data and Variables

3.2. Empirical Model

3.2.1. Panel Auto-Regressive Distributed Lag (ARDL)

3.2.2. Panel Cointegration Regression

3.2.3. Dumitrescu and Hurlin (DH) Panel Causality Test

3.2.4. Stability Diagnostics

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Findings from Panel Unit Root Testing

4.2. Results of ARDL

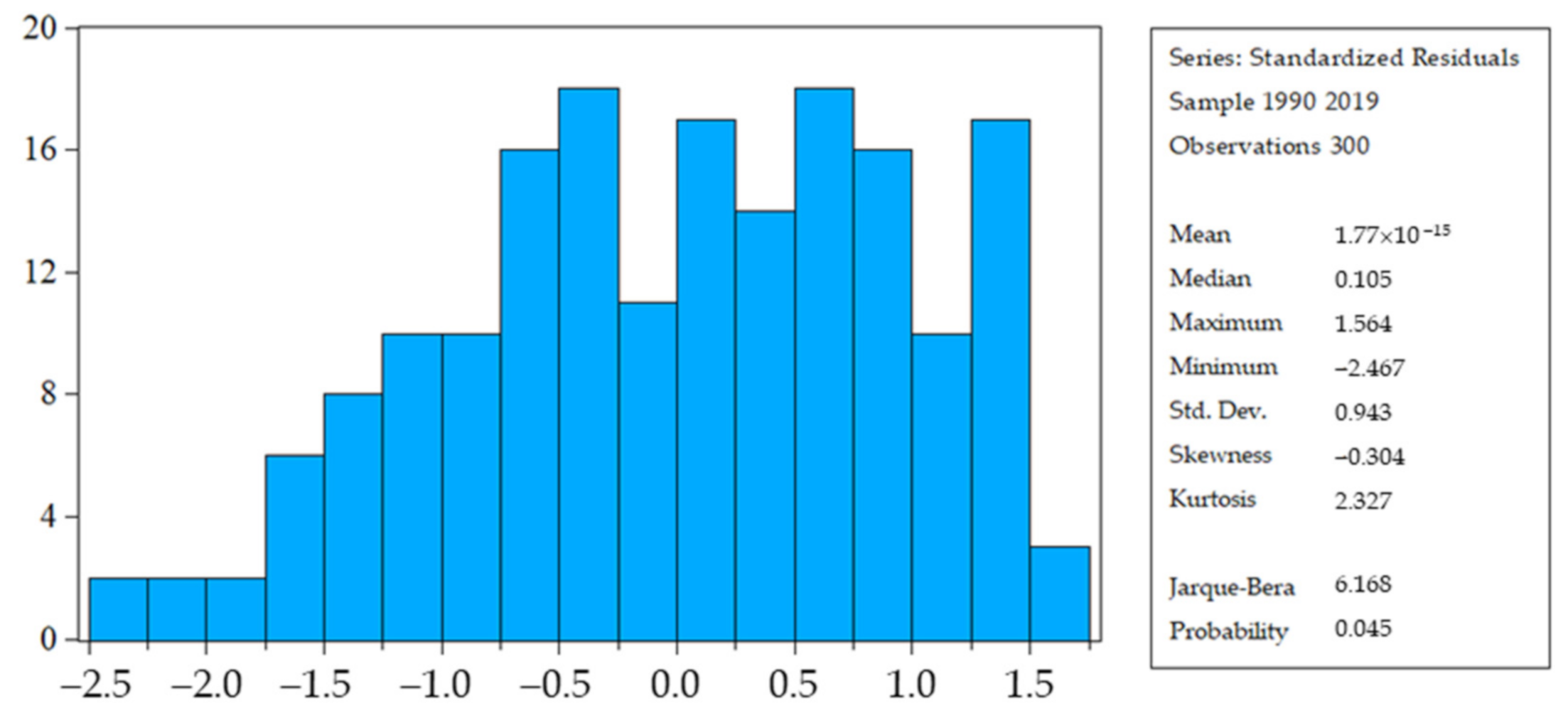

Descriptive Statistics of Standardized Residuals

4.3. Results of Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS) and Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares (DOLS)

4.4. Results of DH Granger Causality

4.5. Results of Stability Diagnostics

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salvatore, D. Twin Deficits in the G-7 Countries and Global Structural Imbalances. J. Policy Model. 2006, 28, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, W.-Y.; Yip, T.-M. The Nexus between Fiscal Deficits and Economic Growth in ASEAN. J. Southeast Asian Econ. 2019, 36, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magazzino, C. The Relationship between Revenue and Expenditure in the ASEAN Countries. East Asia 2014, 31, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Comtrade Database; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Covid-19 Emergency Packages in Southeast Asia. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/southeastasiaandpacific/en/what-we-do/anti-corruption/topics/covid-19.html (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- ADO. Asian Development Outlook (ADO) 2020: What Drives Innovation in Asia? Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eichengreen, B.J. Financial Crises: And What to Do About Them; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; Volume 206. [Google Scholar]

- Magazzino, C. The Twin Deficits in the ASEAN Countries. Evolut. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCAP. The Impact of COVID-19 on South-East Asia; UNESCAP: Bangkok, Thailand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Magazzino, C. The Twin Deficits Phenomenon: Evidence from Italy. J. Econ. Cooper. Dev. 2012, 33, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, F.; Magazzino, C. Twin Deficits in the European Countries. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2013, 19, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, L.H. Tax Policy and International Competitiveness. In International Aspects of Fiscal Policies; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1988; pp. 349–386. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.-H.; Kim, D. Does Korea have Twin Deficits? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2006, 13, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abell, J.D. Twin deficits during the 1980s: An empirical investigation. J. Macroecon. 1990, 12, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, G.; Müller, G.J. Twin deficits: Squaring theory, evidence and common sense. Econ. Policy 2006, 21, 598–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leachman, L.L.; Francis, B. Twin deficits: Apparition or reality? Appl. Econ. 2002, 34, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normandin, M. Budget deficit persistence and the twin deficits hypothesis. J. Int. Econ. 1999, 49, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiku, L.; Bexheti, A.; Bexheti, G.; Bilic, S. Empirical Analyses of the Relationship between Trade and Budget Deficit of FYR of Macedonia. KnE Soc. Sci. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, T. The Effect of Budget Deficit on Current Account Deficit in Ethiopia: Investigating the Twin Deficits Hypothesis. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2018, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furceri, D.; Zdzienicka, M.A. Twin Deficits in Developing Economies; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Behera, H.K.; Yadav, I.S. Explaining India’s Current Account Deficit: A Time Series Perspective. J. Asian Bus. Econ. Stud. 2019, 26, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerakoon, D. Sri Lanka’s Macroeconomic Challenges: A Tale of Two Deficits; Asian Development Bank: Metro Manila, Philippines, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasoğlu, O.F.; İmrohoroğlu, A.; Kabukçuoğlu, A. The Turkish Current Account Deficit. Econ. Inq. 2019, 57, 515–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, G. Are “Twin Deficits” Asymmetric? Evidence on Government Budget and Current Account Balances, 1870–2013. Int. Econ. 2019, 158, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharumshah, A.Z.; Ismail, H.; Lau, E. Twin Deficits Hypothesis and Capital Mobility: The ASEAN-5 Perspective. J. Pengur. UKM J. Manag. 2009, 29, 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, M.; Linnemann, L. Tax and Spending Shocks in the Open Economy: Are the Deficits Twins? Eur. Econ. Rev. 2019, 120, 103300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.; Mansor, S.A.; Puah, C.-H. Revival of the Twin Deficits in Asian Crisis-Affected Countries. Econ. Issues 2010, 15, 29–53. [Google Scholar]

- Banday, U.; Aneja, R. How Budget Deficit and Current Account Deficit are Interrelated in Indian Economy. Theor. Appl. Econ. 2016, 23, 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Shastri, S. Re-examining the Twin Deficit Hypothesis for Major South Asian Economies. Indian Growth Dev. Rev. 2019, 12, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, K.; Munir, K. Dynamics of Twin Deficits in South Asian Countriesk; University Library of Munich, Germany: Munich, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shastri, S.; Giri, A.; Mohapatra, G. An empirical Investigation of the Twin Deficit Hypothesis: Panel Evidence from Selected Asian Economies. J. Econ. Res. 2017, 22, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- ADB. Connecting South Asia and Southeast Asia; Asian Development Bank: Tokyo, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Anoruo, E.; Ramchander, S. Current Account and Fiscal Deficits: Evidence from five developing economies of Asia. J. Asian Econ. 1998, 9, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bon, N. Current Account and Fiscal Deficits-evidence of Twin Divergence from Selected Developing Economies of Asia. Southeast Asian J. Econ. 2014, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank (Ed.) World Development Indicators; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ADB (Ed.) The Asian Development Bank Database; The AD Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baharumshah, A.Z.; Lau, E. Dynamics of Fiscal and Current Account Deficits in Thailand: An Empirical Investigation. J. Econ. Stud. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.; Lin, C.-F.; Chu, C.-S.J. Unit Root Tests in Panel Data: Asymptotic and Finite-Sample Properties. J. Econ. 2002, 108, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, K.S.; Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y. Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J. Econ. 2003, 115, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, B. Econometric Analysis of Panel Data; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, I. Unit Root Tests for Panel Data. J. Int. Money Financ. 2001, 20, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddala, G.S.; Wu, S. A Comparative Study of Unit Root Tests with Panel Data and a New Simple Test. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 1999, 61, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. Statistical Methods for Research Workers. In Breakthroughs in Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y. An Autoregressive Distributed-lag Modelling Approach to Cointegration Analysis. Econ. Soc. Monogr. 1998, 31, 371–413. [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman, C.; Abdul-Rahim, A. Population Growth and CO2 Emission in Nigeria: A Recursive ARDL Approach. Sage Open 2018, 8, 2158244018765916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, P.; Guo, X. The Long-run and Short-run Impacts of Urbanization on Carbon Dioxide Emissions. Econ. Model. 2016, 53, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.C.; Moon, H.R. Linear Regression Limit Theory for Nonstationary Panel Data. Econometrica 1999, 67, 1057–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.; Chiang, M.-H. On the Estimation and Inference of a Cointegrated Regression in Panel Data; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 1999; pp. 179–222. [Google Scholar]

- McCoskey, S.; Kao, C. A Residual-based Test of the Null of Cointegration in Panel Data. Econ. Rev. 1998, 17, 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P. Fully Modified OLS for Heterogeneous Cointegrated Panels. In Nonstationary Panels, Panel Cointegration, and Dynamic Panels; Badi, H.B., Thomas, B.F., Hill, R.C., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2001; Volume 15, pp. 93–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu, E.-I.; Hurlin, C. Testing for Granger Non-causality in Heterogeneous Panels. Econ. Model. 2012, 29, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L.; Weber, S. Testing for Granger Causality in Panel Data. Stata J. 2017, 17, 972–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoch, J.; Hanousek, J.; Horváth, L.; Hušková, M.; Wang, S. Structural breaks in Panel Data: Large Number of Panels and Short Length Time Series. Econ. Rev. 2019, 38, 828–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciak, M.; Pešta, M.; Peštová, B. Changepoint in Dependent and Non-stationary Panels. Stat. Pap. 2020, 61, 1385–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S.No | Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN-10) Countries | Fiscal Deficit (% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP)) | Expenditures to Support Çoronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19 (% of GDP)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brunei Darussalam | −17.94 | 3.4 |

| 2 | Cambodia | −6.5 | 2.3 |

| 3 | Indonesia | −6.6 | 2 |

| 4 | Malaysia | −6.53 | 20.29 |

| 5 | Myanmar | −5.4 | 19 |

| 7 | Philippines | −7.5 | 5.83 |

| 8 | Singapore | −10.77 | 19.88 |

| 9 | Thailand | −5.21 | 3.5 |

| 10 | Vietnam | −6.02 | 1.6 |

| References | Country | Timespan | Methods | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [27] | Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines | 1976–2008 | Granger causality | Current Account Deficit (CAD)↔Fiscal Deficit (FD) (Philippines) CAD→FD (Indonesia) FD→CAD (Malaysia, Thailand) |

| [8] | ASEAN-6, 10 | 1980–2012 | Maddala and Wu and Pesaran’s panel unit root. Westerlund’s Panel co-integration.Panel Granger causality | The predominance of Ricardian equivalence in Southeast Asia. |

| [28] | South Asia | 1990–2013 | Co-integration, Granger Causality | Twin deficit exists in India |

| [29] | Major South Asian Economies | 1985–2016 | Auto-Regressive Distributed Lag (ARDL), Toda Yamamoto fully modified ordinary least squares (FMOLS), dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS) | CAD↔FD (India, Bangladesh) FD→CAD (Pakistan, Sri Lanka) CAD→FD (Nepal) |

| [30] | South Asian countries | 1981–2014 | ARDL Granger causality | The Ricardian equivalent hypothesis is supported in India and Pakistan. CAD↔FD (Bangladesh) |

| [31] | South Asia, Southeast Asia | 1985–2014 | Panel co-integration for long-run analysis. Dumitrescu and Hurlin (DH) panel causality | FD↔CAD |

| Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. | Median | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Account Deficit (CAD) | 9.27 | 0.76 | 9.37 | 0.63 | 2.09 |

| Exchange Rate (EXC) | 2.05 | 1.55 | 1.62 | 0.14 | 1.37 |

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | 10.65 | 0.74 | 10.83 | 0.31 | 2.03 |

| Interest Rate (IR) | 4.45 | 8.07 | 4.62 | 0.48 | 7.82 |

| Fiscal Deficit (FD) | −1.23 | 5.28 | −2.46 | 2.04 | 11.55 |

| Panel Unit Root Methods | Im, Pesaran, Shin (Individual Root) | Levin, Lin and Chu (Common Unit Root Process) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | At Level | At First Difference | At Level | At First Difference |

| Current Account Deficit (CAD) | −0.883 (0.18) | −7.858 (0.00) *** | −1.392 (0.11) | −7.456 (0.00) *** |

| Fiscal Deficit (FD) | −1.115 (0.13) | −6.300 (0.00) *** | 0.008 (0.50) | −5.246 (0.00) *** |

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | 6.264 (0.96) | −2.338 (0.009) *** | 5.829 (0.93) | −4.935 (0.00) *** |

| Exchange Rate (EXC) | 0.904 (0.81) | −2.502 (0.006) *** | −0.101 (0.45) | −3.703 (0.00) *** |

| Interest Rate (IR) | −5.627 (0.00) *** | --- | −2.825 (0.002) *** | --- |

| Dependent Variable Current Account Deficit (CAD) | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long Run Equation | ||||

| Interest Rate (IR) | 0.017 | 0.013 | 1.329 | 0.186 |

| Exchange Rate (EXC) | 0.019 | 0.004 | 3.927 | 0.0002 *** |

| Fiscal Deficit (FD) | 0.063 | 0.011 | 5.417 | 0.000 *** |

| Short Run Equation | ||||

| COINTEQ01 | −0.924 | 0.229 | −4.037 | 0.0001 *** |

| Δ (CAD(−1)) | 0.011 | 0.156 | 0.076 | 0.939 |

| Δ(IR) | 0.020 | 0.032 | 0.622 | 0.535 |

| Δ (IR(−1)) | −0.007 | 0.019 | −0.390 | 0.697 |

| Δ (EXC) | 0.438 | 0.344 | 1.271 | 0.206 |

| Δ (EXC(−1)) | −0.113 | 0.082 | −1.369 | 0.174 |

| Δ (FD) | −0.068 | 0.048 | −1.394 | 0.166 |

| Δ (FD(−1)) | −0.040 | 0.030 | −1.338 | 0.183 |

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | 0.841 | 0.446 | 1.881 | 0.062 * |

| Constant (C) | −1.264 | 3.517 | −0.359 | 0.720 |

| Variables | Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS) | Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares (DOLS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable Current Account Deficit (CAD) | Coefficient | t-Statistics (Prob.) | Coefficient | t-Statistics (Prob.) |

| Interest Rate (IR) | 0.022 | 2.077 (0.039) ** | 0.048 | 1.568 (0.121) |

| Exchange Rate (EXC) | 0.001 | 2.095 (0.037) ** | 0.002 | 1.901(0.061) * |

| Fiscal Deficit (FD) | 0.022 | 1.870 (0.062) * | 0.092 | 1.780 (0.083) * |

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | 0.001 | 3.160 (0.001) *** | 0.001 | 0.961 (0.34) |

| R2 | 0.550 | 0.940 | ||

| Null Hypothesis | W-Stat | Zbar-Stat | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Account Deficit (CAD)does not cause Fiscal Deficit (FD) | 4.56 | 2.33 | 0.01 *** |

| FD does not cause CAD | 1.53 | −0.92 | 0.35 |

| Interest Rate (IR) does not cause CAD | 4.17 | 1.90 | 0.05 ** |

| CAD does not cause IR | 2.75 | 0.38 | 0.69 |

| FD does not cause Exchange Rate (EXC) | 1.700 | −0.75 | 0.45 |

| EXC does not cause FD | 1.90 | −0.53 | 0.59 |

| FD does not cause IR | 2.40 | 0.004 | 0.99 |

| IR does not cause FD | 4.15 | 1.88 | 0.05 ** |

| EXC does not cause IR | 1.47 | −0.99 | 0.32 |

| IR does not cause EXC | 2.80 | 0.43 | 0.66 |

| EXC does not cause CAD | 3.12 | 0.77 | 0.43 |

| CAD does not cause EXC | 4.17 | 1.91 | 0.05 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marimuthu, M.; Khan, H.; Bangash, R. Reverse Causality between Fiscal and Current Account Deficits in ASEAN: Evidence from Panel Econometric Analysis. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9101124

Marimuthu M, Khan H, Bangash R. Reverse Causality between Fiscal and Current Account Deficits in ASEAN: Evidence from Panel Econometric Analysis. Mathematics. 2021; 9(10):1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9101124

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarimuthu, Maran, Hanana Khan, and Romana Bangash. 2021. "Reverse Causality between Fiscal and Current Account Deficits in ASEAN: Evidence from Panel Econometric Analysis" Mathematics 9, no. 10: 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9101124

APA StyleMarimuthu, M., Khan, H., & Bangash, R. (2021). Reverse Causality between Fiscal and Current Account Deficits in ASEAN: Evidence from Panel Econometric Analysis. Mathematics, 9(10), 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9101124